Abstract

The differential diagnosis of syncope versus seizures represents a daily challenge for cardiologists and neurologists. Long Q-T syndrome and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) are two hereditary arrhythmogenic heart conditions causing syncope in early adulthood. We report the cases of two patients who were reassessed for transient loss of consciousness (TLOC) with convulsions despite treatment. The first patient, a 40-year-old woman, had been diagnosed with epilepsy and was given phenytoin. Her episodes took place while swimming or when in emotional distress and were not followed by post-ictal confusion. An electrocardiogram showed a very prolonged Q-Tc interval. The second patient, a 30-year-old man with HCM in whom a defibrillator had been implanted on the assumption that he was having cardiogenic syncopes, was actually found to have epilepsy. Adequate treatment rendered both patients asymptomatic. In conclusion, the clinical history and 12-lead electrocardiography remain crucial in the management of TLOC, ideally involving both cardiologists and neurologists.

BACKGROUND

Syncope and palpitations were recognised by Lancisi and Albertini as distinctive cardiological symptoms (conmotio cordis and palpitatio cordis, respectively) as early as the 18th century.1 Furthermore, pallor of the face and loss of consciousness were among the first phenomena that were identified to occur in the context of an epileptic seizure. Hence in 1856, writing on epilepsy, cosmopolitan neurologist Brown-Séquard realised the difficulties in the differential diagnosis, stating that “the brain proper loses at once its functions, just as it does in a complete syncope”.2

Nowadays, distinguishing between epileptic seizures and syncope still presents a daily challenge for cardiologists and neurologists. Long Q-T syndrome and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) are two hereditary arrhythmogenic heart conditions typically leading to recurrent syncope in early adulthood and both can, as a consequence, be mistaken for epilepsy. Because of the significantly increased risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) associated with both diseases,3 a prompt and accurate diagnosis is of paramount importance. Therefore, the clinical history remains a basic but nonetheless crucial instrument in guiding us through to the right diagnosis.

CASE PRESENTATION

We report the cases of two patients with long Q-T syndrome and HCM, respectively, who were reassessed for recurrent transient loss of consciousness (TLOC) and convulsions in spite of treatment. One patient, a 40-year-old female, who had been diagnosed with epilepsy in her teens and in whom phenytoin had been prescribed and whose sister was being investigated for heart rhythm problems, was admitted to casualty following a TLOC. A year prior to admission she was rescued from a swimming pool with an aborted cardiac arrest. Six months later, during her father’s funeral she had another episode accompanied by “snow-white” pallor and generalised myoclonic jerks but without tongue biting or post-ictal confusion.

A 30-year-old male with HCM whose brother was known to have obstructive HCM, had a cardioverter-defibrillator implanted. This decision was mainly based on the assumption that he was having recurrent cardiogenic syncope. Despite this, he repeatedly presented to casualty with TLOC. He described paroxysmal stereotyped experiential phenomena and complex auditory hallucinations consisting of loud familiar music sometimes leading to secondarily generalised tonic-clonic seizures with lateral tongue biting, prolonged post-ictal confusion and complete memory loss for over half an hour following the seizure.

INVESTIGATIONS

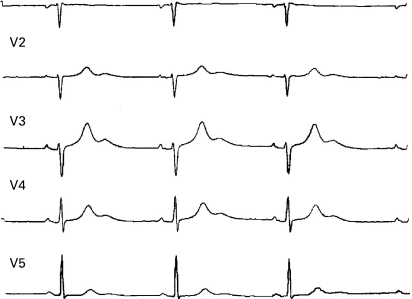

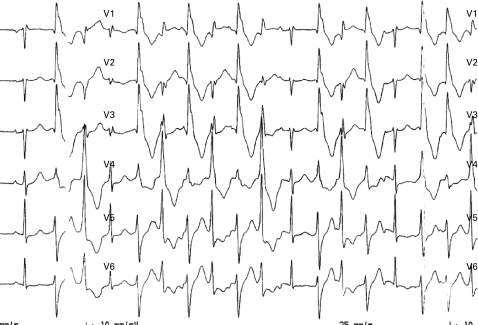

In our first patient, relevant investigations included a 12-lead electrocardiogram carried out in the accident and emergency department which revealed a Q-Tc interval >760 ms (fig 1), while electrophysiological provoking tests showed a non-sustained polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (fig 2) rather than the torsade de pointes typically associated with long Q-T. In our second patient, no signs of obstruction or arrhythmia were found after appropriate cardiological investigations. An MRI of the brain could not be carried out due to the presence of the defibrillator. A CT of the head was normal, while an EEG showed interictal epileptiform activity localised over the right temporal region.

Figure 1.

ECG showing a corrected Q-Tc interval of 760 ms (V3).

Figure 2.

Stress-induced polymorphic ventricular non-sustained tachycardia.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The clinical history and 12-lead electrocardiography are essential in the differential diagnosis of syncope versus seizures, particularly in the young adult population.

Whereas the episodes of TLOC in the first patient were the result of recurrent convulsive syncope (instead of epilepsy), the second patient most likely had partial and secondarily generalised seizures in the context of localisation related cryptogenic epilepsy (instead of cardiogenic syncope).

TREATMENT

In our first patient, phenytoin was changed to propranolol. Our second patient was prescribed oxcarbazepine.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

In our first patient, an emotion-triggered syncope took place 6 months later and a defibrillator (ICD) was permanently implanted and the dose of propranolol was readjusted, rendering the patient symptom free so far. The patient’s sister was later confirmed to have long Q-T syndrome. In our second patient, oxcarbazepine 600 mg successfully prevented further seizures.

DISCUSSION

Epileptic seizures without convulsions were recognised by John Hughlings Jackson two centuries ago,4 and varying degrees of involuntary movements, ranging from brief myoclonic jerks to tonic-clonic movements (most likely associated with cerebral hypoperfusion leading to a predominantly non-epileptic anoxic phenomenon) typically occur in syncope.5

Neurologists and cardiologists have independently found that a misdiagnosis of syncope for seizures or vice versa can occur in one third of patients.6 However, the diagnostic yield of a non-invasive clinical evaluation, including symptom-based targeted testing, was as high as 76%.7 Starting a treatment generally implies a diagnosis and while delaying an epilepsy diagnosis hardly results in any harm, a false positive can have serious consequences,8 not least from a psychosocial point of view.9

Long Q-T syndrome is a heterogeneous heart condition that can lead to ventricular tachycardia and SCD.10 Our first patient had an inherited form (most likely LQT1, classically known as Romano–Ward syndrome) and the history of recurrent syncope and the length of the interval significantly increased the risk of SCD.11 Phenytoin is a well recognised antiepileptic drug with anti-arrhythmogenic properties which can in theory shorten the Q-T interval through sodium-channel blockage12 and mask an underlying arrhythmia that requires a radically different approach. In our first case it could be argued that “the right treatment had been given for the wrong reason”, as phenytoin had been used in the past as second line treatment for long Q-T syndrome on account of its known anti-arrhythmogenic function. In any case, an electrocardiogram in the context of the patient’s acute admission had shown a very prolonged Q-Tc interval regardless of a proven good compliancy to phenytoin.

HCM is an inherited disease with marked phenotypic variability. Syncope and pre-syncope occur in 15–25% of patients and an increased recurrence has been associated with an increased risk of SCD.13 However, the high-risk status of HCM is yet to be established, and the indication for pacing remains controversial.14 The assumption that TLOC in our second patient was the result of cardiogenic syncope led to the unnecessary implantation of a defibrillator.

Recent reports on sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) suggest that this yet to be understood condition seems to be largely linked with generalised tonic-clonic seizures in the context of refractory epilepsy, with nearly a 1% risk in patients awaiting epilepsy surgery.15 On the other hand, no convincing link has been established between the very rare occurrence of ictal asystole (typically identified with temporal or frontal lobe epilepsies) and SUDEP.16 While further investigations are needed in order to clarify whether a direct relationship between seizure-induced heart rhythm problems and SUDEP exists, it seems more than possible that certain cases of SUDEP could have been the result of a misdiagnosed underlying arrhythmogenic heart disease. Furthermore, syncope and seizures rarely coexist.17

In conclusion, in the past as at present the clinical history remains the cornerstone in the management of TLOC. Particularly in the young adult population, a family history of sudden death and/or arrhythmias should draw the attention towards potentially fatal, yet treatable underlying heart conditions such as long Q-T syndrome and HCM. A 12-lead electrocardiogram can prevent SCD from channelopathies such as long Q-T syndrome and Brugada syndrome (the latter having only been recognised as a distinct clinical entity causing ventricular fibrillation fairly recently)18 as well as from cardiomyopathies,19 but additional investigations such as electrophysiological tests,20 and indeed simultaneous video electrocardiography–electroencephalography may be necessary.

LEARNING POINTS

Treatment failure for syncope and/or seizures warrants a review of the diagnosis.

Usually, only cases with poor or even fatal outcomes trigger reflections that subsequently lead to a change in practice.

The favourable outcome of our cases however should be taken into account, particularly in view of the risks involved.

In a fast-track epilepsy clinic, it is useful to have an electrocardiographic interpretation guide.

A co-ordinated approach by cardiologists and neurologists is essential in the management of transient loss of consciousness.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr AG Marson for pointing out the fact that long Q-T syndrome can be missed in a 12-lead baseline ECG.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Laín Entralgo P. Historia de la medicina. Barcelona: Salvat, 1974 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown-Séquard E. Experimental and clinical researches applied to physiology and pathology. The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 1856; 56: 475–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basso C, Corrado D, Thiene G. Cardiovascular causes of sudden death in young individuals including athletes. Cardiol Rev 1999; 7: 127–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughlings Jackson J. Selected writings of John Hughlings Jackson. Vol 1.On epilepsy and epileptiform convulsions. New York: James Taylor, 1958 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kapoor WN. Syncope. N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 1856–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith D, Defalla BA, Chadwick DW. The misdiagnosis of epilepsy and the management of refractory epilepsy in a specialist clinic. QJM 1999; 92: 15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarasin FP, Louis-Simonet M, Carballo D, et al. Prospective evaluation of patients with syncope: a population-based study. Am J Med 2001; 111: 177–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chadwick D. Epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1994; 57: 264–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker GA, Jacoby A, Buck D, et al. Quality of life of people with epilepsy: a European study. Epilepsia 1997; 38: 353–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moss AJ, Schwartz PJ, Crampton RS, et al. The long QT syndrome: prospective longitudinal study of 328 families. Circulation 1991; 84: 1136–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Spazzolini C, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation in the long-QT syndrome: gene-specific triggers for life-threatening arrhythmias. Circulation 2001; 103: 89–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golan DE. Principles of pharmacology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams L, Frenneaux M. Syncope in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: mechanisms and consequences for treatment. Europace 2007; 9: 817–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cannon III RO. Assessing risk in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 1016–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomson T, Nashef L, Ryvlin P. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: current knowledge and future directions. Lancet Neurol 2008; 7: 1021–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuelle SU, Bermeo AC, Locatelli E, et al. Ictal asystole: a benign condition? Epilepsia 2008; 49: 168–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gastaut H, Fishcher-Williams M. Electro-encephalographic study of syncope. Its differentiation from epilepsy. Lancet 1957; 2: 1018–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 20: 1391–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papadakis M, Whyte G, Sharma S. Preparticipation screening for cardiovascular abnormalities in young competitive athletes. BMJ 2008; 337: a1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nader A, Massumi A, Cheng J, et al. Inherited arrhythmic disorders: long QT and Brugada syndromes. Tex Heart Inst J 2007; 34: 67–75 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]