Abstract

Differentiating intestinal tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease is one of the most difficult and challenging issues for the gastroenterologist, radiologist and pathologist. The final diagnosis of such cases may need the gathering of all clinical, endoscopic, radiological and pathological data. In the following report three cases of intestinal tuberculosis are described. Two of these were initially misdiagnosed as Crohn’s disease and the third was thought to be ovarian or colonic cancer; a fourth patient was diagnosed as having Crohn’s disease but on presentation was thought to have intestinal tuberculosis. Their clinical presentations, colonoscopic findings, radiological features and the pathological diagnosis are described and the similarities between intestinal tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease as compared to previous reports are discussed.

Introduction

Tuberculosis is very prevalent in Saudi Arabia1,2 with pulmonary and variable presentations of extra-pulmonary tuberculosis being reported. In addition, large numbers of visitors from different Asian and African endemic areas visit Saudi Arabia for the Hajj and all year round during Omra.3 Intestinal tuberculosis is one of the common extra-pulmonary manifestations of tuberculosis.4 In addition, Crohn’s disease is increasingly being diagnosed in Saudi Arabia among Saudi and non-Saudi patients.5 However, there are difficulties in differentiating intestinal tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease because of similarities in the radiological, endoscopic and pathological features of both diseases. Previously reported data addressed some of the clinical and pathological differences between the two conditions, but the criteria used are not always applicable.6–8 More recently, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for mycobacterium has been utilised for the diagnosis of tuberculosis, but only 61%–74.4% of intestinal tuberculosis cases were positive by PCR. Therefore, one third of patient could be missed if PCR is used as the only diagnostic method.8 Anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody (ASCA), which is often positive in patients with Crohn’s disease, was not found to be of value in differentiating intestinal tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease.6,9 Positive culture of acid fast bacilli (AFB) on intestinal biopsy or surgical specimens would give an accurate diagnosis of tuberculosis but it takes 4–6 weeks, which would result in delayed treatment. Culture may be better reserved for determining sensitivity to anti-tuberculosis medications. The positive tuberculin test (PPB) may help to establish the diagnosis in endemic tuberculosis areas, but some patients with active tuberculosis and advanced disease may have a false negative result because of protein depletion or a false positive result in case of previous BCG vaccination.10 This confusion in differentiating intestinal tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease will result in delayed treatment of intestinal tuberculosis or Crohn’s disease, leading to disease progression and complications. On the other hand, patients with active tuberculosis will be at risk of disseminating the infection if they receive steroids or immunosuppressants for possible Crohn’s disease, while patients with Crohn’s disease receiving treatment for tuberculosis will be unnecessarily subjected to the side effects of anti-tuberculosis treatment.

Case presentation

First patient

A 17-year-old previously well girl presented to the emergency department with right iliac fossa (RIF) pain of 6 days’ duration. The pain was severe, colicky in nature and associated with diarrhoea and vomiting. There was no fever or other gastrointestinal symptoms and a review of the patient’s systems was unremarkable.

She was ill looking, thin and afebrile with a regular pulse of 131 bpm of normal volume. Blood pressure was 103/66 mm Hg. The chest and cardiovascular examination were normal. Examination of the abdomen revealed moderate rebound tenderness with an ill-defined small mass in the RIF.

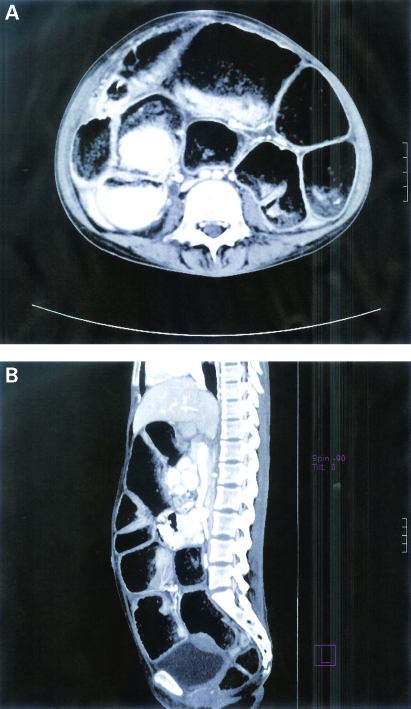

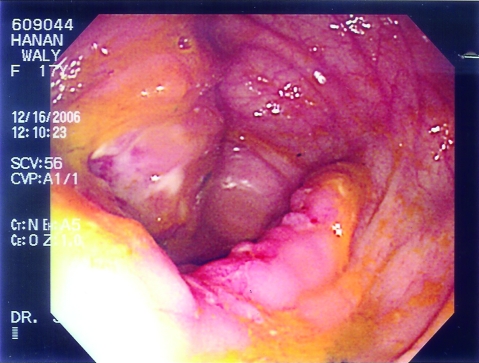

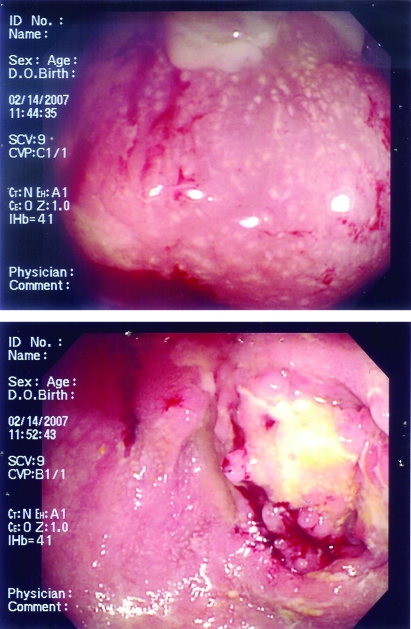

Complete blood count (CBC) showed haemoglobin (Hb) 10.9 g/dl (normal 12–15), white blood count (WBC) 9.6×103/μl (normal 4.5–11×103/μl), neutrophils 70%, lymphocytes 20% and platelets 648 k/μl (normal 150–450 k/μl). Electrolytes, renal function and blood sugar were normal. Corrected calcium was normal. Albumin was 27 g/l (normal 35–50). Total protein and the liver enzymes were normal apart from alkaline phosphatase which was 174 (normal 50–136), but this level was expected for the patient’s age. Serum amylase was also normal. HIV 1 and 2 were negative. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 20, which is normal. Chest x-ray was normal. Abdomen and pelvic CT scan showed thickening of the ileal and cecal walls with secondary chronic obstructed dilated distal ileal loops. Multiple enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes were seen. Fat stranding of the mesentery was also noted. Intestinal tuberculosis was considered possible but Crohn’s disease was another option (figure 1A,B). A small bowel enema showed an irregular thread-like narrowing in the distal ileal segment (the contrast did not pass beyond the stricture) and dilated ileal loops proximal to the stricture, suggesting tuberculosis rather than Crohn’s disease or lymphoma. Colonoscopy showed inflammation, friability and exudate formation with large ulcerated areas of the cecum and a stenosed ileocecal valve; the terminal ileum could not be accessed (figure 2). Colonic biopsy showed evidence of cryptitis and crypt abscess formation, and basal plasma cytosis and one non-caseating granuloma was noted; Ziehl-Neelsen stain was negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The pathological impression was more consistent with inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease) than tuberculosis.

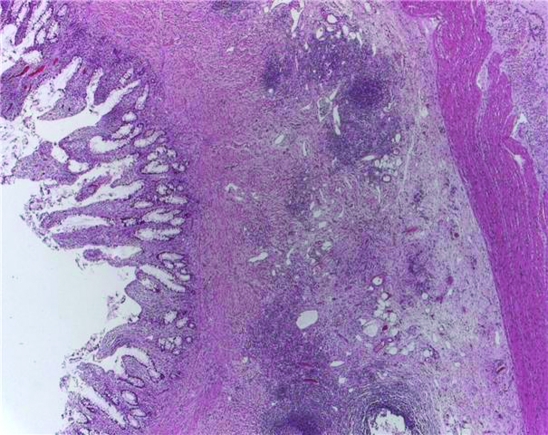

Figure 1.

(A,B) The first patient’s CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed thickening of the ileal and cecal walls with secondary chronic obstructed dilated distal ileal loops. Multiple enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes were seen. Fat stranding of the mesentery was also noted.

Figure 2.

The first patient’s colonoscopic examination showed inflammation, loss of normal vascular pattern, friability and exudate formation with large ulcerated areas of the cecum and a narrowing at the ileocecal valve region.

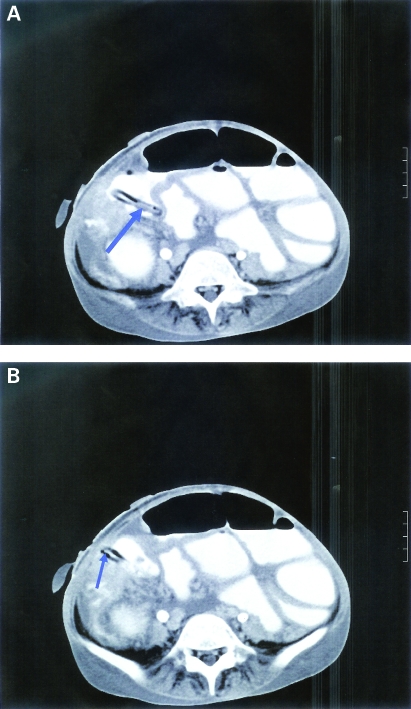

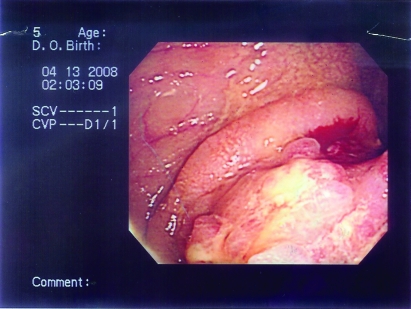

The patient was started on prednisolone 20 mg per day and azathioprine 50 mg per day. She continued on this treatment for a few weeks until she was lost to follow-up. However, 5 months later she presented to another hospital with RIF pain and mass. She underwent surgery for appendicular mass. The biopsy results were consistent with tuberculosis and showed foreign body giant cell epithelioid caseating granuloma. She was started on anti-tuberculosis treatment, but once again she stopped treatment and was lost to follow-up. Two months after the surgery she returned with an 8-week history of poor appetite, weight loss, and RIF abscess that opened to the anterior abdominal wall as a fistula discharging a large amount of fecal material. She was resumed on anti-tuberculosis medications: isoniazid (INH) 200 mg per day, rifampicin 300 mg per day, ethambutol 400 mg on alternate days, pyrazinamide 1 g per day, with vitamin B6 40 mg per day. As the patient weighed only 26.4 kg and her height was 150 cm, the doses were weight adjusted. The patient was discharged on anti-tuberculosis medication, but 2 weeks later she was readmitted with acute abdominal pain and Gram-negative sepsis. A CT scan of the abdomen showed a thickened narrowed terminal ileum, thickened cecum and other areas of the colon with luminal narrowing; a right lower abdominal fistula was seen between the terminal ileum and the skin and there was a moderate amount of ascites (figure 3A,B). Repeated colonoscopy revealed severe narrowing of the sigmoid colon with a large inflammatory mass seen at 45 cm from the anal verge (figure 4). Biopsy of the narrowed segment and of the mass showed chronic focal active colitis without granuloma or evidence of malignancy; the final report was consistent with inflammatory bowel disease. PCR for M tuberculosis was negative. The patient was started on broad spectrum antibiotics and fluid resuscitation but her condition deteriorated and she died in the ICU 10 months after initial presentation.

Figure 3.

The first patient’s follow-up CT scan of the abdomen showing a thickened narrowed terminal ileum, thickened cecum and other the parts of the colon with luminal narrowing. A right lower abdominal fistula (arrow) was seen between the terminal ileum and the skin. There was also a moderate amount of ascites.

Figure 4.

Follow-up colonoscopy of the first patient after deterioration showed severe narrowing of the sigmoid colon with a large polypoid inflammatory mass seen at 45 cm from the anal verge.

Second patient

A 39-year-old woman was seen in the surgical outpatient department because of a 2-year history of progressive RIF pain which improved following fasting or vomiting. She also noticed a fullness in her RIF. On examination she was afebrile with BP 100/60 mm Hg with a normal pulse of 85 bpm. She had a tender RIF mass measuring about 6×5 cm and a perianal fistula. The rest of the examination was unremarkable. CBC showed Hb 10.7 g/l, WBC 4.9 k/μl, 64% neutrophils and platelets 385 k/μl. Electrolytes, renal function and liver function were normal apart from albumin of 26 g/l (normal 35–50). The patient was HIV 1 and 2 negative. ESR was 96 mm/h (normal 1–20). Chest x-ray was normal. A purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test was strongly positive with induration measuring 20×15 mm. CT scan of the abdomen showed a huge mass with heterogeneous density in the RIF measuring 7.4×8.7×12 cm extending to the terminal ileum, the ileocecal junction and the cecum associated with thickening of the bowel and fat stranding causing narrowing of the lumen (figure 5).

Figure 5.

The second patient’s CT scan of the abdomen showed a huge heterogeneous density mass in the right iliac fossa measuring 7.4×8.7×12 cm extending to the terminal ileum, the ileocecal junction and the cecum. Thickening of the bowel and fat stranding causing narrowing of the lumen were also seen.

The patient underwent a colonoscopy which showed inflammation, friability and ulceration with loss of the mucosal vascular pattern involving the cecum and narrowing at the ileocecal valve region (figure 6). Endoscopic colonic biopsy showed well defined epithelioid granuloma, inflammatory cell infiltrate and the inflammatory process extending to the submucosa, suggesting inflammatory bowel disease consistent with Crohn’s disease.

Figure 6.

The second patient’s colonoscopic pictures showing inflammation, friability, ulceration, exudation and inflammatory polyps formation. Loss of the mucosal vascular pattern in the cecum and narrowing at the ileocecal valve are also seen.

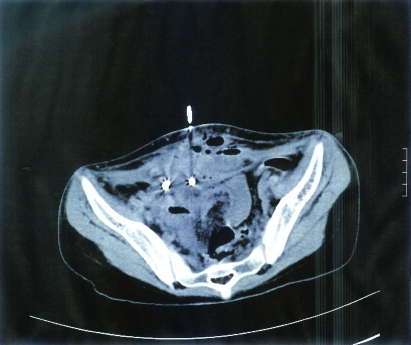

The patient was started on Pentasa (mesalamine) 1 g three times per day, oral prednisolone 30 mg per day and azathioprine 50 mg per day, and was discharged home and followed closely in the outpatient clinic. Over the following 18 months the abdominal pain persisted and the RIF mass gradually increased in size to form a large abscess. A follow-up CT scan of the abdomen 1 year later showed a huge mass measuring 6×9.5×13 cm with heterogeneous soft tissue density in the RIF extending to the terminal ileum, the ileocecal junction and the cecum reaching to the hepatic flexure. There was thickening and narrowing of the bowel, but no fistula was seen. Azathioprine was increased to 100 mg per day and prednisolone was gradually reduced, but the patient’s condition worsened. A CT scan 2 months later showed that the RIF mass was enlarging and forming an abscess, associated with right abdominal wall collection, a fistula arising between the ascending colon and the abdominal wall muscle collection, and psoas abscess. The patient was admitted three times with high grade fever for CT guided drainage of the abscess. On two occasions culture of the drained content was positive for Gram-negative bacilli but AFB stain was negative. She received multiple courses of intravenous and oral antibiotics. Fever subsided and the abdominal wall collection resolved. Later on the fistula opened to the anterior abdominal wall; it was draining a large amount of pus without signs of inflammation (cold abscess). At that point the patient had lost 6 kg in weight, her Hb had dropped to 7.9 g/l and she had finished 20 months of treatment for Crohn’s disease. Infliximab (TNF1α Ab) as treatment for refractory Crohn’s disease was not considered because of recurrent uncontrolled infection. Azathioprine and prednisolone were stopped. AFB PCR and AFB culture were obtained on three occasions from the RIF drain and she was started on tuberculosis treatment with four drugs: isoniazid (INH) 300 mg per day, rifampicin 600 mg per day, ethambutol 1.2 g per day and pyrazinamide 1.5 g per day, with vitamin B6 40 mg per day. The results of AFB PCR and tuberculosis culture were negative. Two months after she was started on anti-tuberculosis treatment, the RIF mass had significantly decreased in size and the opening of the fistula at the anterior abdominal wall had become much smaller (figure 7). Ethambutol and pyrazinamide were stopped and rifampicin and INH were continued. Over the following 6 months the fistula completely closed. On her most recent follow-up the patient was asymptomatic; anti-tuberculosis medication was stopped after 12 months of treatment.

Figure 7.

The second patient’s colonoscopic findings 2 months after anti-TB treatment was started showed marked improvement of the inflammation and ulceration in the ileocecal region.

Third patient

A 15-year-old female was admitted to the hospital with a 2-week history of RIF pain and mass. She had been unwell for a year with dull aching abdominal pain, infrequent vomiting, low grade fever and progressive weight loss. Her past history was unremarkable and there was pyrazinamide

On examination she was febrile with a temperature of 39°C, BP 90/60 mm Hg and a pulse of 120 bpm. Her weight was 27 kg and her height was 146 cm. Examination of the abdomen revealed a 7×7 cm RIF mass; the non-tender the skin was intact over the mass. The rest of her physical examination was normal.

CBC showed WBC 11.2 k/μl, Hb 8.5 g/l and platelets 534 k/μl. ESR was 34 (normal 1–20), C reactive protein was 35 mg/l (normal 0–3). Electrolytes, renal function, blood sugar and liver enzymes were all normal. Albumin was 13 g/l. Chest x-ray was normal. A CT scan of the abdomen showed a multiloculated pelvic abscess extending to the anterior abdominal wall, possibly secondary to complicated appendicular abscess (figure 8). Colonoscopy showed severe inflammation and severe narrowing of the cecum and the ileocecal region; the scope was not advanced to the terminal ileum (figure 9). The colonic biopsy was consistent with inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease). Due to active infection the patient was not started on prednisolone or azathioprine. She was started on Pentasa (mesalamine) 1 g three times per day, broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics and she had CT scan guided drainage of the abscess with insertion of drains. Culture of the drained pus was positive for Enterobacter cloacae; AFB stain and culture were negative. The pelvic collection did not resolve completely after the CT guided drainage. Three weeks after her initial presentation the patient had distal ileal resection with limited right hemicolectomy and primary anastomosis. Pathological examination of the excised tissue showed chronic inflammatory fistula and the ileocecal margin revealed foreign body giant cell reaction, Paneth cell hyperplasia, and transmural mononuclear cell infiltration; no granuloma was seen. The picture was consistent with Crohn’s disease (figure 10). Molecular biology for M tuberculosis (PCR detection) on the tissue and the AFB culture from the surgical specimen were negative. Post operatively the patient was stable and gradually resumed oral feeding. On discharge she was maintained on Pentasa 1 g three times a day. Over the following 4 months she gained 10 kg in weight. Currently she is receiving the same dose of Pentasa and is asymptomatic.

Figure 8.

The third patient’s CT scan of the abdomen showed a multiloculated pelvic abscess extending to the anterior abdominal wall. The film also showed a needle which was introduced to the abscess for drainage.

Figure 9.

The third patient’s colonoscopy showed inflammation with loss of vascular pattern and severe narrowing of the ileocecal valve.

Figure 10.

Histology of part of the excised bowel mucosa of the third patient showed foreign body giant cell reaction, Paneth cell hyperplasia, and transmural mononuclear cell infiltration. No granuloma was seen.

Fourth patient

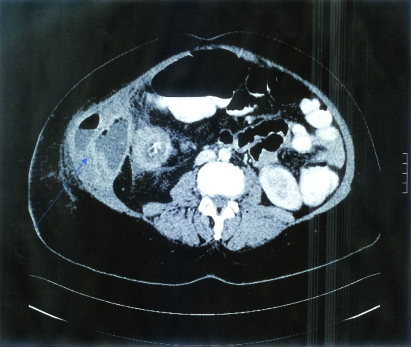

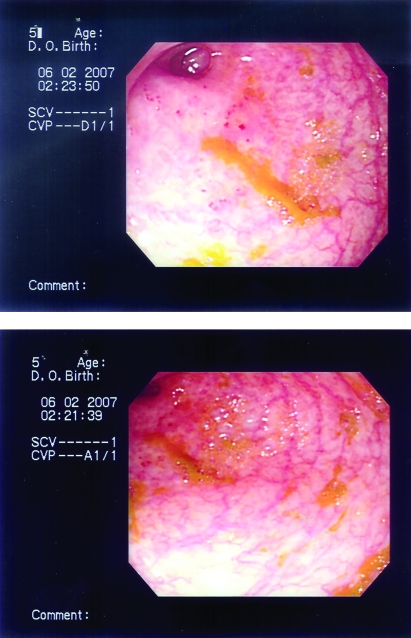

A 33-year-old woman had progressive abdominal distension and low grade fever for 3 weeks. There was no other significant past history or recent complaints and she had had no contact with tuberculosis. She is a hospital ward clerk. On examination she was afebrile with a temperature of 37°C, a regular pulse of 107 bpm, and BP 110/77 mm Hg. Examination of the abdomen revealed massive ascites. The rest of the examination was normal. CBC showed WBC 6.6 k/μl, neutrophils 59.7%, lymphocytes 32.7%, Hb 11.3 g/l and platelets 383 k/μl. ESR was 69 (normal 1–20). Electrolytes, renal function and liver function were normal. The patient was HIV 1 and 2 negative. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) was normal, CA125 was 937 (normal 0–35) and alphafetoprotein was normal. Analysis of the ascitic fluid showed exudate with protein 68 g/l and lactate dehydrogenase 266 U/l. The fluid cell count showed WBC 1355/CU MM, polymorphs 14%, lymphocytes 4% and monocytes 70%. PCR for M tuberculosis from the fluid was not carried out. Cytology of the fluid was negative for malignancy. A CT scan of the abdomen showed circumferential abnormal wall thickening of the ascending colon and the hepatic flexure with paracolic fat stranding, multiple mesenteric and precaval large lymph nodes, a large amount of free ascites and left side pleural effusion; the ovaries were normal. Based on the CT results, carcinoma of the colon was the most likely diagnosis (figure 11). However, colonoscopy revealed severe inflammation with multiple large deep ulcers, necrosis and inflammatory polyp formation involving the ascending colon and the cecum, indicating either tuberculous colitis or Crohn’s disease; the terminal ileum was normal (figure 12). Endoscopic colonic biopsy showed marked infiltration of acute and chronic inflammatory cells, cryptitis and crypt abscesses, and multiple caseating granulomas with Langerhan’s giant cells, consistent with tuberculosis. The patient was started on four anti-tuberculosis drugs: isoniazid (INH) 300 mg per day, rifampicin 600 mg per day, ethambutol 1.2 g per day and pyrazinamide 1.5 g per day, with vitamin B6 40 mg per day. Ethambutol and pyrazinamide were stopped after 2 months. Six months after diagnosis the patient was free of symptoms, and an ultrasound of the abdomen showed no ascites. Treatment with anti-tuberculosis treatment was continued for 1 year and then stopped.

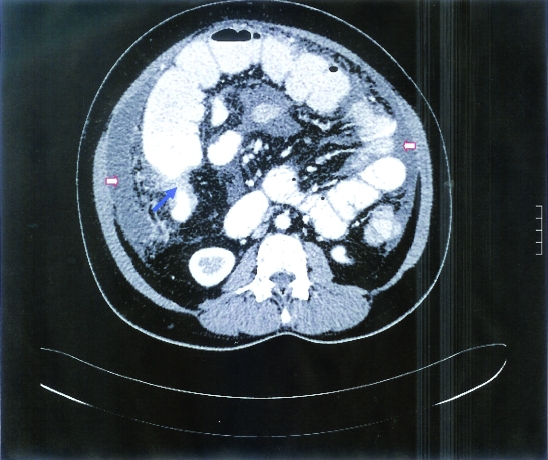

Figure 11.

The fourth patient’s CT scan of the abdomen showed circumferential abnormal wall thickening of the colon lumen (blue arrow) with paracolic fat stranding; multiple mesenteric and precaval large lymph nodes were seen. There was a large amount of free ascites (red arrows).

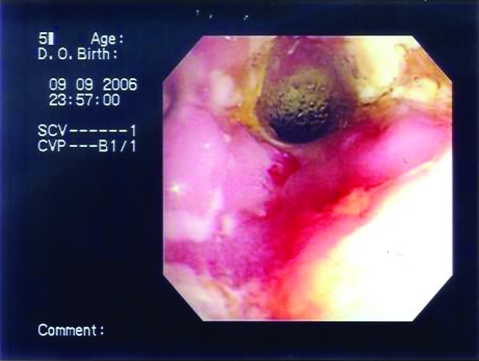

Figure 12.

The fourth patient’s colonoscopy showed inflammation with multiple large deep ulcers, necrosis and inflammatory polyp formation indicating either tuberculous colitis or Crohn’s disease.

Discussion

The difficulties described above in differentiating intestinal tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease are not unusual.11

The first patient had a tragic outcome because of delayed diagnosis and poor compliance with follow-up and treatment. She was first diagnosed as having Crohn’s disease based on endoscopic biopsy findings; at that time she had had watery diarrhoea for few days, which would support a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease rather than intestinal tuberculosis as reported by Amarapurkar and colleagues.6 Shortly after discharge she stopped treatment and was lost to follow-up. On her second admission to another hospital the result of the surgical specimen was consistent with tuberculosis, with caseating granuloma seen on histological examination of the excised section. She was started on anti-tuberculosis medication but once again stopped treatment. On her last admission she was very ill and wasted and had a very low albumin level. With severe malnutrition and impaired immunity she had severe Gram-negative sepsis, and optimal intensive care and intravenous antibiotics were not effective. Because of the more advanced disease, as seen on CT scan and colonoscopy, and poor health status, she had a poor response to the anti-tuberculosis therapy when the treatment was resumed during her last admission.

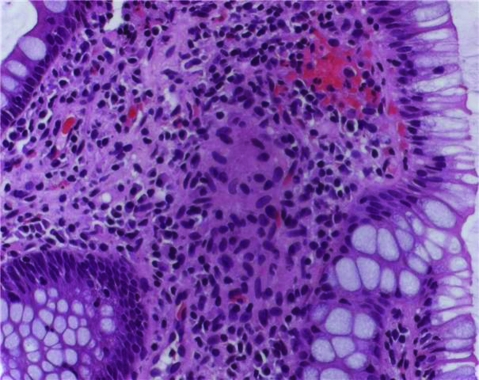

The pathological features of the second patient with RIF mass were suggestive of Crohn’s disease (figure 13); the non-caseating granuloma from the colonic biopsy of this patient can be found in both tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease. A diagnosis of Crohn’s disease was supported by the presence of a perianal fistula. Patel and colleagues suggested that perianal disease, fistulae and extra-intestinal features support a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease rather than tuberculosis in such patients.11 When she was started on prednisolone and azathioprine the abdominal pain improved, possibly because of the anti-inflammatory effect of prednisolone. After 20 months of treatment for Crohn’s disease the decision was made to change the patient to anti-tuberculosis treatment based on clinical evidence of the presence of a cold abscess, positive PPD and failure of treatment of suspected Crohn’s disease. She had a remarkable response to anti-tuberculosis medication and closure of the fistula. She was frequently tested for AFB from the RIF abscess aspirate and the colonic biopsy by PCR and culture, but no positive result was obtained. Misdiagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis as Crohn’s disease as in her case is not unusual and similar to a previous report by Patel and colleagues who reported a 66.5% rate of histological and microbiological proof of tuberculosis in 260 patients with luminal tuberculosis.11 A strongly positive tuberculosis skin test on initial presentation supported a diagnosis tuberculosis but it was overlooked following the radiological and pathological findings. Compared to the first patient, this patient’s compliance with follow-up helped the failure to respond to Crohn’s disease treatment to be recognised and discovery of disease progression before it became too advanced.

Figure 13.

Colonic biopsy from the ileocecal region of the second patient showing non-caseating granuloma that can be seen in both tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease.

The third patient was straightforward as she had multiple pelvic abscesses and localisation rather than the skip disease pattern normally seen on abdominal CT exam. Tuberculosis was considered but the pathological diagnosis on the excised section of the colon was consistent with Crohn’s disease. She had excellent clinical improvement after surgery. She was maintained only on mesalamine under regular close follow-up in case of disease recurrence.

Features of transmural inflammation seen in figure 10 (colonic biopsy from patient 3) can be seen both in Crohn’s disease and in intestinal tuberculosis similar to that of the second patient.

The fourth patient posed a different challenge. As she presented with massive ascites, ovarian tumour was at the top of the differential diagnosis list. This was supported by positive CA125 (tumour marker for ovarian cancer), but other intra-abdominal conditions such as tuberculosis can cause similar elevations in CA125.12 An abdominal CT scan raised the possibility of cancer colon. However, the colonoscopic findings were consistent with either intestinal tuberculosis or Crohn’s disease, but tuberculosis was more likely because of the presence of ascites.6,12 Crohn’s disease presenting with massive ascites is rare, as reported by Paspatis and colleagues.13 The final diagnosis of tuberculosis in this patient was confirmed by colonic biopsy showing caseating granuloma which is specific for tuberculosis but not for Crohn’s disease.7,8 She had complete response to anti-tuberculosis treatment and was spared having major surgery for possible cancer.

Diagnosing intestinal tuberculosis is problematic in some patients because the clinical and radiological features of intestinal tuberculosis may mimic Crohn’s disease, carcinoma or lymphoma.4,14 Colonoscopic and pathological features of intestinal tuberculosis are very difficult to distinguish from those of Crohn’s disease, but the presence of extra-intestinal manifestations of Crohn’s disease, radiological features of pulmonary tuberculosis or a positive PCR test for AFB will help in establishing the diagnosis.7,11 The tuberculin skin test is a simple diagnostic tool that should be used as it is helpful in the diagnosis of tuberculosis in even highly endemic areas and after neonatal BCG vaccination.10 New tests such as the QuantiFERON-TB test (based on quantification of interferon gamma) are approved for the diagnosis of latent M tuberculosis infection.15 More recently, in 2005 the CDC approved the use of the QuantiFERON-TB Gold test for diagnosing active tuberculosis,16 but this blood based test is not yet available in our centre. In some patients diagnosis will only be confirmed after response to treatment.4 So far, there is no gold standard method to differentiate intestinal tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease although choosing the correct diagnostic methods can lead to a higher accuracy in diagnosis.4

Learning points

Abdominal tuberculosis in areas endemic for tuberculosis can have variable presentations that mimic other abdominal pathology.

It is sometimes difficult to differentiate intestinal tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease clinically, radiologically and pathologically, but gathering of data will reduce the chance of misdiagnosis.

In cases of non-response to treatment, a wrong diagnosis should be assumed and additional work-up is warranted.

Patient understanding of the importance of medical follow-up and treatment is essential to differentiate poor compliance from non-response to treatment or misdiagnosis.

Detailed review of available radiological and pathological data of large number of intestinal tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease patients may help in determining specific radiological and pathological features that can discriminate intestinal tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease.

Conclusion

Intestinal tuberculosis is a common presentation of extra-pulmonary tuberculosis. At the same time, Crohn’s disease is increasingly recognised in Saudi Arabia. Confusion between the two diseases can arise from similarities in their clinical, endoscopic, radiological and pathological features. Misdiagnosis will result in incorrect or delayed treatment. In Saudi Arabia and other countries endemic for tuberculosis, more precise clinical, radiological and possibly immunological criteria are needed to differentiate between the two conditions.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bener A, Abdullah AK. Reaction to tuberculin testing in Saudi Arabia. Indian J Public Health 1993; 37: 105–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koshak EA, Tawfeeq RZ. Tuberculin reactivity among health care workers at King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J 2003; 9: 1034–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilder-Smith A, Foo W, Earnest A, et al. High risk of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection during the Hajj pilgrimage. Trop Med Int Health 2005; 10: 336–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uygur-Bayramicli O, Dabak G, Dabak R. A clinical dilemma: abdominal tuberculosis. World J Gastroenterol 2003; 9: 1098–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Ghamdi AS, Al-Mofleh IA, Al-Rashed RS, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of Crohn’s disease in a teaching hospital in Riyadh. World J Gastroenterol 20041; 10: 1341–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amarapurkar DN, Patel ND, Rane PS. Diagnosis of Crohn’s disease in India where tuberculosis is widely prevalent. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14: 741–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirsch R, Pentecost M, Hall P de M, et al. Role of colonoscopic biopsy in distinguishing between Crohn’s disease and intestinal tuberculosis. J Clin Pathol 2006; 59: 840–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gan HT, Chen YQ, Ouyang Q, et al. Differentiation between intestinal tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease in endoscopic biopsy specimens by polymerase chain reaction. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97: 1446–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghoshal UC, Ghoshal U, Singh H, et al. Anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody is not useful to differentiate between Crohn’s disease and intestinal tuberculosis in India. J Postgrad Med 2007; 53: 166–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Jahdali H, Memish ZA, Menzies D. The utility and interpretation of tuberculin skin tests in the Middle East. Am J Infect Control 2005; 33: 151–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel N, Amarapurkar D, Agal S, et al. Gastrointestinal luminal tuberculosis: establishing the diagnosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 19: 1240–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uzunkoy A, Harma M, Harma M. Diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis: experience from 11 cases and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10: 3647–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paspatis GA, Kissamitaki V, Kyriakakis E, et al. Ascites associated with the initial presentation of Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 94: 1974–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engin G, Balk E. Imaging findings of intestinal tuberculosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2005; 29: 37–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazurek GH, Villarino ME. Guidelines for using the QuantiFERON-TB test for diagnosing latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. MMWR Recomm Rep 2003; 52: 15–18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazurek GH, Jereb J, Lobue P, et al. Guidelines for using the QuantiFERON-TB Gold test for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, United States. MMWR Recomm Rep 2005; 54: 49–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]