Abstract

Spontaneous spinal subdural haematoma (SSDH) with no underlying pathology is a very rare condition. Only 20 cases have been previously reported. It can be caused by abnormalities of coagulation, blood dyscrasia, or trauma, underlying neoplasm, and arteriovenous malformation. It occurs most commonly in the thoracic spine and presents with sudden back pain radiating to the arms, legs or trunk, and varying degrees of motor, sensory, and autonomic disturbances. Although the main approach to management is surgical decompression, conservative management is used as well. We report the case of a 57-year-old man who presented with sudden severe low back pain followed by rapid onset of complete paraplegia. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed an anterior subdural haematoma from T9 to L1 with cord compression. Corticosteroid treatment was administered. The patient showed substantial clinical improvement after 7 days of bed rest and an intense rehabilitation programme. An MRI scan and a computed tomography angiogram did not reveal any underlying pathology to account for the subdural haematoma.

Background

Acute spinal subdural haematoma (SSDH) is an exceedingly uncommon and potentially life threatening condition. The formation of acute SSDHs may result from iatrogenic causes such as spinal puncture or epidural anaesthesia, sometimes associated with coagulation abnormalities.1,2 Nevertheless, spontaneous onset should also be considered in patients receiving anticoagulant therapy or those with bleeding disorders, who show signs of rapid spinal cord or cauda equina compression.3 More than 100 cases of non-traumatic acute SSDH have been reported and reviewed by Domenicucci et al.4 Only 20 SSDHs are documented to have occurred in the absence of these underlying conditions (table 1). Recognition in the few first hours after onset is important because they may lead to spinal cord compression.5 The first magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) descriptions were reported in 1990.6–8 We report the case of a man in his 50s with spontaneous non-traumatic acute SSDH who made a rapid and good neurological recovery following conservative treatment and a rehabilitation programme. We also review the literature and discuss the aetiology, pathogenesis, clinical features, imaging, and prognosis of spontaneous SSDH.

Table 1.

Cases of spontaneous spinal subdural haematoma with no underlying pathology published in the literature

| Reference | Year | Age | Sex | Level | Location | SAH | Surgery | Recovery |

| Ainsle | 1958 | 67 | F | T8–T10 | Dorsal | No | Yes | Good |

| Banach | 1970 | 65 | F | T3–T5 | – | No | No | Death |

| Anagnostopoulus | 1972 | 63 | F | T8–T12 | Dorsal | No | Yes | Poor |

| Reynolds | 1978 | ? | ? | Cervical | ? | No | No | Death |

| Sakata | 1984 | 56 | M | L3–L5 | Dorsal | No | Yes | Full |

| Swann | 1984 | 46 | F | L2–L5 | Ventral | Yes | P/CDr | Full |

| Martinez | 1987 | 64 | M | T5–T6 | Ventral | No | Yes | Good |

| Grobovschek | 1989 | 38 | F | Thorasic | Ventral | No | No | Poor |

| Grobovschek | 1989 | 41 | F | C3–L2 | Dorsal | No | No | Poor |

| Levy | 1990 | 43 | M | L4–L5 | Dorsal | No | Yes | Full |

| Levy | 1990 | 81 | F | L5 | Dorsal | No | P/CDr | Full |

| Mavroudakis | 1990 | 38 | M | T1–T2 | Ventral | Yes | No | Full |

| Jacquet | 1991 | 51 | M | T6–T8 | Dorsal | Yes | Yes | Good |

| Grunberg | 1993 | 70 | F | T3–L3 | Ventral | No | No | Good |

| Longatti | 1994 | 54 | M | T5–L5 | Ventral | Yes | No | Full |

| Kang | 2000 | 49 | F | T5–L3 | Ventral | Yes | No | Full |

| Kuker | 2000 | 81 | M | Thorasic | Ventral | ? | Yes | Full |

| Kuker | 2000 | 56 | F | Th–Lu | Ventral | ? | Yes | Good |

| Boukobza | 2001 | 74 | M | T6–L4 | Dorsal | ? | No | Full |

| Athanasios | 2007 | 44 | M | T2–T6 | Anterior | No | Yes | Good |

F, female; M, male; P/CDr, percutaneous drainage; SAH, subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Case presentation

A 57-year-old man presented with sudden severe low back pain. The pain spread rapidly as a burning sensation to the lower limbs, and his legs became so weak he could not walk. A short time later, complete insensitivity and powerlessness affected both his lower extremities. This developed while he was walking on the street. He was asymptomatic apart from a mild headache during the 24 h before this episode. His complaints began 4 h before admission to the emergency department. There was no history of trauma, coagulation defect, or use of drugs. Blood pressure was 130/90 mm Hg, pulse was 78/min. Physical examination showed flaccid paralysis of both legs with areflexia and loss of all sensation below T10 bilaterally. Deep tendon reflexes were not brisk and Babinski’s sign was absent bilaterally. Both knee and ankle reflexes were not brisk. The plantar response was absent bilaterally. He had no sacral sparing of pin prick sensation in S3, S4, and S5 dermatomes. On rectal examination, the anal sphincter was flaccid. The bulbocavernosus and anal reflexes were absent. He had no sensation of bladder fullness or following insertion of an indwelling catheter.

The results of blood tests showed a platelet count of 145×103/μl, a prothrombin time of 15 s, an international normalised ratio (INR) of 1.19, and a partial thromboplastin time of 25.6 s. An urgent MRI scan of the thoracolumbar spine was performed (figs 1 and 2). In sagittal sections, an anterior subdural haematoma extending from T9 to L1 was determined (fig 1). In T1 weighted hypo-isointense images and in T2 weighed hyperintense images, a haematoma was visualised. The epidural fat was preserved, confirming the location of the haematoma. The axial images demonstrated posterior displacement of the spinal cord at this level (fig 2).

Figure 1.

Sagittal TI and T2 weighted magnetic resonance images 4 h after onset of symptoms, showing a slightly hyperintense longitudinal space occupying lesion extending from T9 to L1 in the anterior spinal canal on a sagittal spin echo T1 weighted image.

Figure 2.

On an axial fast T2 weighted image at L1, a hyperintense lesion is shown.

For treatment, we initially planned to perform an emergency laminectomy, but instead opted for medical treatment with corticosteroids. A loading dose of methylprednisolone, 30 mg/kg intravenously (IV), was administered within 15 min, followed 45 min later with a continuous infusion of methylprednisolone at a dose rate of 5.4 mg/kg/h IV for 23 h. Mannitol 20% was also administered, at a dosage of 1 mg/kg IV three times daily, over a 24 h period. Twenty-four hours after initiation of corticosteroid treatment, two of the five complaints (insensitivity and powerlessness) of the patient had improved.

Three days after the onset of symptoms, the patient was transferred to a rehabilitation centre for further management and rehabilitation. Full neurologic examination was performed on admission. Six days after admission, high resolution axial computed tomography (CT) scans showed no evidence of abnormal vessels within the spinal canal or the paraspinal region (figs 3 and 4). An MRI scan of the brain was also negative.

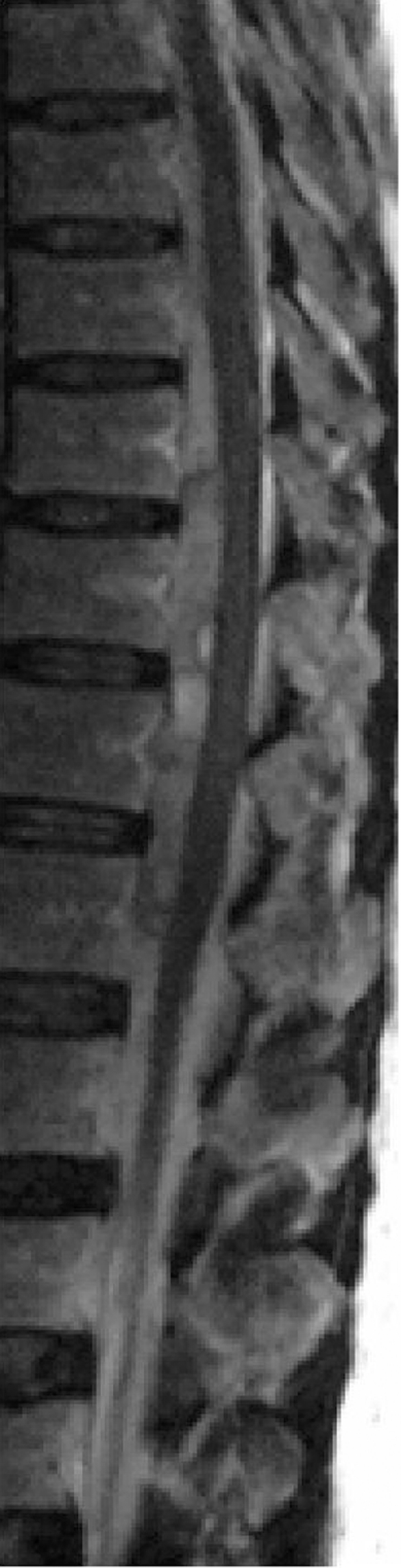

Figure 3.

The haematoma is absent in a sagittal T1 weighted image taken 7 days after the onset of symptoms. The canal is clear, and 7 days later the clinical examination was also normal.

Figure 4.

An axial image (7 days after treatment) shows no compression on the spinal cord.

The management of the patient in our centre included a further 7 days of bed rest with spinal nursing and regular turns to prevent pressure sores. Bladder management changed to self intermittent catheterisation by the second day of admission. Intensive respiratory physiotherapy, general strengthening exercises, and hydrotherapy following mobilisation were performed. Regular detailed neurologic examinations revealed rapid and significant neurologic improvement and a full range of motion in all muscle groups in the lower extremities. By the time the patient was discharged from our centre 7 days after he first presented with paralysis, he was able to walk. He had regained good motor power in both lower extremities (5/5 on the left and 5/5 on the right). He did not develop spasticity in both lower extremities, and did not require intermittent catheterisation for bladder management upon discharge. The patient was fully independent in all transfers and self-care, and motor power had fully recovered in both lower extremities. Unfortunately, we had no opportunity to perform digital angiography post-treatment to determine whether or not there was evidence of abnormal vessels within the spinal canal or the paraspinal region.

Discussion

The cause and origin of SSHs in the subdural space are undefined. They may occur without any obvious cause.9–12 Their development may be related to a variety of factors: anticoagulant therapy, coagulopathies (idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura,13 polycythaemia,14 leukaemia and severe liver failure15) and after poisoning with rodenticides of the coumarin group.8 SSH is a recognised but statistically rare complication in patients given spinal anaesthesia.16–20 There are risk factors for this condition: traumatic spinal lumbar puncture, multiple spinal punctures,1,15 particularly needles that stray from the midline,21 peridural catheterisation, coagulopathy14 or anticoagulant therapy,22 and the venous dilatation that occurs at the end of pregnancy.21 SSH has also been reported in association with eclampsia.23 None of these causes were determined in our case, which was spontaneous.

SSHs may be associated with subarachnoid haemorrhage, manifesting with elevated intracranial pressure13,24 or with subdural intracranial haematoma25–28 occurring after mild cranial trauma. Rader29 proposed that a forgotten effort or minor trauma can increase both the intrathoracic and intraluminal pressure of the vessels traversing the subarachnoid space. When the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure lags behind the intravascular pressure, the vessels rupture resulting in subarachnoid haemorrhage. The same sudden increase in pressures can cause rupture of the small extra-arachnoidal vessels located on the inner surface of the dura, resulting in a subdural haemorrhage. Several authors30–33 have described the presence of combined subdural and subarachnoid haemorrhage in the same patient. This has led them to suggest that subdural haemorrhage may have originated in the more vascular subarachnoid space and passed through the thin and delicate arachnoid membrane. However, the diluting and redistributing effect of the CSF prevents clot formation unless the haematoma is sufficiently large to block the CSF flow. Conversely, the origin of the haematoma can be the subdural space and it can then pass through the arachnoid membrane, giving rise to an associated subarachnoid haemorrhage. There are queries whether this small delicate network of vessels can be the source of hemorrhage.9 It is difficult to determine if the blood that was found in the subarachnoid space is the result of the surgical procedure or was present before surgery.

Only 20 cases of acute spontaneous SSDH have been reported (table 1).34–36 It occurs most commonly in the thoracic spine, and there is no gender predominance. There is, however, a slightly higher incidence between the fourth to sixth decades of life. Usually, the onset is acute with sudden back pain radiating to the arms, legs or trunk, and varying degrees of motor, sensory, and autonomic disturbances. Headache is an unusual initial symptom once reported in the past.6 The time from onset to the development of neurologic deficit varies from a few hours to 3 weeks. The degree of deficit also varies from mild motor sensory and sphincter deficit to complete paraplegia.

Thin section CT scan with sagittal reconstructions performed in the acute stage of an SSDH demonstrates high density material delineated by the thin dura and separate from the epidural fat, which demonstrates a very low fat density on CT. However, after the acute stage, the density of the haematoma will decrease, and this can make the identification of the haematoma difficult. MRI best depicts the extent of the haemorrhage and the delineation from the epidural space. While the signal characteristics are variable depending on the age of the haematoma, SSDH usually demonstrates high signal intensity on T1 weighted images. T2 weighted images can be misleading as the haematoma can have the same signal as the CSF.3 In our case, in T1 weighted hypo-isointense images and in T2 weighted hyperintense images, the haematoma was present. Axial MRI best demonstrates the intradural location of the blood. The haematoma can be ventral or dorsal to the cord and can demonstrate various shapes, including crescent, biconvex, circumferential, or a mixture of shapes at different levels.3 Our patient had an anterior haematoma with a variable shape at different levels. The craniocaudal extent is variable but is more than in epidural haematomas, which are usually over two to three vertebrae in length. The haematoma in our patient extended between T9 and L1.

Epidural haematomas are more common than subdural, have a lentiform or convex shape, have a tapering superior and inferior extension, and form an obtuse margin with the ligamentum flavum; there is effacement with the epidural fat. MRI can also demonstrate better the underlying cause of the haematoma and can identify alternate causes of the clinical features, such as tumours and vascular malformations (AVM). AVMs are best demonstrated on gradient echo sequences. Angiography is the best modality for identifying vascular malformations. Currently, CT angiography is performed as it is less invasive and, if performed correctly, can identify AVM as well.3

Three treatment options for SSDH have been described: (1) conservative management, in cases with mild neurologic deficit and early progressive improvement; (2) emergency surgical decompression in cases with acute deterioration and severe neurologic deficit; and (3) percutaneous drainage, in extensive dorsally located haematomas. Conservative treatment is possible if an early recovery is observed,7,10,13,16,25,37–39 if the deficits are mild, if the degree of extension precludes surgical treatment,39 or if a coagulopathy is associated.13,15 In our case, the presence of blood in both spaces was not confirmed surgically. The patient responded to the medical treatment rapidly, so we did not need surgical treatment. Rare cases of spontaneous recovery have been reported30 supporting the role of conservative management in selected cases. The most important difference between our case and the cases that improved to full recovery conservatively is the treatment period. Our case improved to full recovery within only 7 days. It has been reported in the literature that only four cases that were treated conservatively improved to make a full recovery.30–32,40 In these cases, in T1 weighted and T2 weighted images, the lesions had extended from T6 to L4. Their full recovery extended from 6–16 weeks.

Spontaneous SSDH is a relatively rare condition. Patients usually demonstrate slow but good neurologic recovery. The literature does not describe adequately the neurologic outcome of these patients. Intensive rehabilitation programmes, including physiotherapy and bladder and bowel management, are vital to ensure a good recovery. Patients with incomplete neurologic deficit tend to recover with or without surgery. Our patient had complete neurological deficit at the lower extremities. After corticosteroid treatment he was fully independent in all transfers and self-care, and his motor power had fully recovered in both lower extremities. As far as we are aware, this is the first report of a patient with acute SSDH who recovered within just 1 week following conservative treatment.

Learning points

A spontaneous non-traumatic spinal subdural haematoma is a very rare condition.

The precipitating factors are still speculative.

MRI best depicts the extent and location of the haemorrhage.

An intensive rehabilitation programme is vital to ensure a good recovery.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication

REFERENCES

- 1.Langmayr JJ, Ortler M, Dessl A, et al. Management of spontaneous extramedullary spinal haematomas: Results in eight patients after MRI diagnosis and surgical decompression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1995; 59: 442–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russel NA, Benoit BG. Spinal subdural hematoma: a review. Surg Neurol 1983; 20: 133–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kyriakides AE, Lalam RK, El Masry WS. Acute spontaneous spinal subdural hematoma presenting as paraplegia. Spine 2007; 32: 619–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Domenicucci M, Ramieri A, Ciappetta P, et al. Nontraumatic acute spinal subdural haematoma: report of five cases and review of the literature. J Neurosurg 1999; 91: 65–73 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boukobza M, Haddar D, Boissonet M, et al. Spinal subdural haematoma: a study of three cases. Clin Radiol 2001; 56: 475–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston RA. The management of acute spinal cord compression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1993; 56: 1046–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy JM. Spontaneous lumbar subdural hematoma. Am J Neuroradiol 1990; 11: 780–81 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mavroudakis N. Spontaneous spinal subdural hematoma: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 1992; 30: 652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nighoghossian N, Ruel JH, French P, et al. Heamatome soubdural cervico–dorsal par intoxication aux raticides coumariniques. Rev Neurol 1990; 146: 221–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calhoun JM, Boop F. Spontaneous spinal subdural haematoma: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 1991; 29: 133–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grunberg A, Carlier R, Bekkali F, et al. Spinal subdural heamatoma. Presentation of 2 cases studied with MRI. J Radiol 1993; 74: 291–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson PJ, Hahn F, McConnell J, et al. The importance of MRI findings for the diagnosis of nontraumatic lumbar subacute subdural haematomas. Acta Neurochir 1991; 113: 186–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morandi X, Carsin-Nicol B, Brassier G, et al. MR demonstration of spontaneous acute spinal subdural hematoma. J Neuroradiol 1998; 25: 46–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benito-Leon J, Leon PG, Ferreiro A, et al. Intracranial hypertension syndrome as an unusual form of presentation of spinal subarachnoid haemorrhage and subdural haematoma. Acta Neurochir 1997; 139: 261–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalina P, Drehobl KE, Black K, et al. Spinal cord compression by spontaneous spinal subdural haematoma in polycythemia vera. Postgrad Med J 1995; 71: 378–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Post MJ, Becerra JL, Madsen PW, et al. Acute spinal subdural hematoma: MR and CT findings with pathologic correlates. Am J Neuroradiol 1994; 15: 1895–905 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bougher RJ, Ramage D. Spinal subdural haematoma following combined spinal-epidural anaesthesia. Anaesth Intensive Care 1995; 23: 373–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pryle BJ, Carter JA, Cadoux-Hudson T. Delayed paraplegia following spinal anaesthesia. Spinal subdural haematoma following dural puncture with a 25 G pencil point needle at T12-L1 in a patient taking aspirin. Anaesthesia 1996; 51: 263–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott DB, Hibbard BM. Serious non-fatal complications associated with extradural block in obstetric practice. Br J Anaesth 1990; 64: 537–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sternlo JE, Hybbinette CH. Spinal subdural bleeding after attempted epidural and subsequent spinal anaesthesia in a patient on thromboprophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1995; 39: 557–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tekkok IH, Carter DA, Brinker R. Spinal subdural haematoma as a complication of immediate epidural blood patch. Can J Anaesth 1996; 43: 306–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pujol S, Torrielli R. Neurological accidents after epidural anesthesia in obstetrics. Cah Anesthesiol 1996; 44: 341–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hernot S, Samii K. Di.erent types of nerve injuries in locoregional anesthesia. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 1997; 16: 274–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lao TT, Halpern SH, MacDonald D, Huh C. Spinal subdural haematoma in a parturient after attempted epidural anaesthesia. Can J Anaesth 1993; 40: 340–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernsen RA, Hoogenraad TU. A spinal haematoma occurring in the subarachnoid as well as in the subdural space in a patient treated with anticoagulants. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 1992; 94: 35–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tillich M, Kammerhuber F, Reittner P, et al. Chronic spinal subdural haematoma associated with intracranial subdural haematoma: CT and MRI. Neuroradiology 1999; 41: 137–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leber KA, Pendl G, Kogler S, et al. Simultaneous spinal and intracranial chronic subdural hematoma. J Neurosurg 1997; 87: 644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee JI, Hong SC, Shin HJ, et al. Traumatic spinal subdural hematoma; rapid resolution after repeated lumbar spinal puncture and drainage. J Trauma 1996; 40: 654–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimada Y, Sato K, Abe E, et al. Spinal subdural hematoma. Skeletal Radiol 1996; 25: 477–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rader JP. Chronic subdural haematoma of the spinal cord. N Engl J Med 1955; 253: 374–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mavroudakis N, Levivier M, Rodesch G. Central cord syndrome due to spontaneously regressive spinal subdural hematoma. Neurol 1990; 40: 1306–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Longatti PL, Freschi P, Moro M, et al. Spontaneous spinal subdural haematoma. J Neurosurg Sci 1994; 38: 197–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang HS, Chung CK, Kim HJ. Spontaneous spinal subdural haematoma with spontaneous resolution. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 192–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jain V, Singh J, Sharma R. Spontaneous concomitant cranial and spinal subdural haematomas with spontaneous resolution. Singapore Med J 2008; 49: 53–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grobovschek M, Schurich H. Spinale subdurale raumforderungenhamatome. Rofo 1989; 150: 20–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacquet G, Godard J, Orabi M, et al. Spinal subdural haematoma. Zentralbl Neurochir 1991; 52: 131–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Küker W, Thiex R, Friese S, et al. Spinal subdural and epidural haematomas: diagnostic and therapeutic aspects in acute and subacute cases. Acta Neurochir 2000; 142: 777–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Juvonen T, Tervonen O, Ukkola V, et al. Widespread posttraumatic spinal subdural haematoma imaging findings with spontaneous resolution: case report. J Trauma 1994; 36: 262–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwerdtfeger K, Caspar W, Alloussi S, et al. Acute spinal intradural extrameduallary hematoma: a nonsurgical approach for spinal cord decompression. Neurosurgery 1990; 27: 312–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kulkarni AV, Willinsky RA, Gray T, et al. Serial magnetic resonance imaging findings for a spontaneously resolving spinal subdural hematoma: case report. Neurosurgery 1998; 42: 398–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]