Abstract

Administration of abatacept is a new treatment modality for rheumatoid arthritis (RA). We describe a patient in whom psoriasiform skin lesions developed 4 months after the initiation of abatacept therapy for longstanding, rheumatoid factor positive RA. Histological findings were consistent with psoriasis. The skin lesions subsided after discontinuation of abatacept and reappeared after re-exposure to the drug, suggesting a causal connection between abatacept and the development of psoriasis.

BACKGROUND

Abatacept has been recently introduced for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) after failure of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) blocking therapy. Abatacept (CTLA4-Ig) is a fully human soluble costimulation modulator that selectively targets the CD80/CD86: CD28 co- stimulatory signal required for full T cell activation.1 It is hypothesised that by decreasing T cell activation and proliferation, abatacept leads to decreased pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion and decreased autoantibody production (for example, rheumatoid factor (RF)) and consequently to a decrease in RA disease activity.2 The efficacy and safety of abatacept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to TNF blocking therapy have been adequately demonstrated.3

Here we present a case of a patient with longstanding RF positive RA who developed new onset psoriasis after four infusions of abatacept. To our knowledge this is the first description of psoriasis associated with the administration of abatacept.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 51-year-old Caucasian woman with a 9 year history of RA presented with symmetric polyarthritis of the metacarpophalangeal joints. She was seropositive for RF and had high titres of antibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptide, as well as increased inflammatory markers. Imaging studies revealed erosive disease. She had no clinical evidence of psoriasiform skin lesions either before or at the time of initiation of abatacept, and there was no family history of psoriasis.

Her previous treatment regimens had included sulfasalazine, methotrexate, leflunomide, anakinra, infliximab, etanercept and rituximab, but all had failed to induce sustained remission.

Due to considerable radiologic progression and continued ongoing synovitis with a disease activity score (DAS28) of 7.6 after 6 months without any disease modifying antirheumatic drug, we started a standard regimen with abatacept with concomitant prednisolone 5 mg daily.

Subsequent follow-up visits showed her condition stabilised and her disease activity score improved from an initial DAS28 of 7.6 to 4.9 after 4 months.

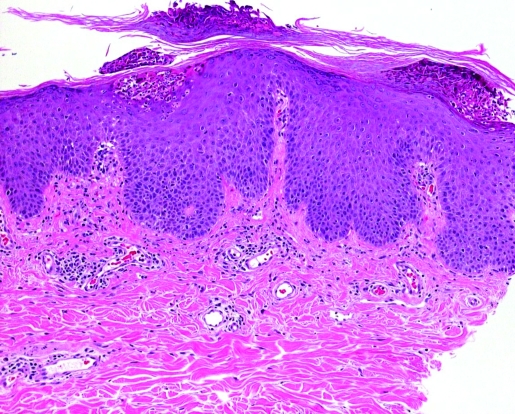

Interestingly, after four monthly courses of intravenous abatacept she developed a few scattered erythematous plaques on her lower legs (fig 1). After an additional dose of abatacept wider spread eruptions with psoriasiform skin lesions developed involving both arms, lower legs and dorsal aspects of the trunk. Histological findings from a skin biopsy showed epidermal hyperplasia with intracorneal collections of neutrophils and parakeratosis, confirming the diagnosis of psoriasis (fig 2). Therefore, abatacept was discontinued and the skin lesions improved substantially under topical treatment with steroids and calcipotriol. Two months later the skin lesions had entirely disappeared.

Figure 1.

Erythematous plaques covered by silvery white scales.

Figure 2.

Epidermal hyperplasia with intracorneal collections of neutrophils and parakeratosis.

After the termination of abatacept her RA exacerbated. Due to the lack of other treatment options and after having obtained informed consent, abatacept was re-established in our patient.

Three weeks later psoriasiform skin lesions reoccurred, the patient required the cessation of this drug and the skin cleared entirely within 6 weeks.

DISCUSSION

We report for the first time a case of new onset of psoriasis in a patient who received abatacept for longstanding RF positive RA. However, the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for this phenomenon remain elusive.

Although many factors contributing to the generation of psoriatic lesions remain unknown, a growing body of evidence suggests a primary T lymphocyte based immunopathogenesis.4 Dermal infiltrates consisting of T cells and macrophages appear in early psoriatic plaques.5 Several compounds specifically targeting T cell function have been found to be effective in the treatment of psoriasis, ciclosporin being one example.4

Recently, considerable effort was undertaken to elucidate a possible role for blocking costimulatory signals between the antigen presenting cells and the T cell in the treatment of psoriasis. Blockade of T lymphocyte costimulation with CTLA4-Ig was found to reverse the cellular pathology of psoriatic plaques, including the activation of keratinocytes, dendritic cells and endothelial cells, therefore suggesting a potential therapeutic use for this novel immunomodulatory approach in T cell mediated diseases such as psoriasis.6 A phase I study investigating the effect of CTLA4-Ig in patients with psoriasis showed some clinical improvement.7

Given this outlined aetiopathogenetic concept the development of psoriasis during the treatment with the T lymphocyte costimulation modulator abatacept is an unexpected event.

One obvious explanation for the occurrence of a psoriasiform rash would be the possibility that our patient actually had psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and that the skin eruption was part of her underlying condition rather than an adverse event of abatacept. PsA is known to be a heterogenic disease, with clinical features that may occasionally resemble RA. Approximately 10% of patients with PsA present with arthritic symptoms before developing the cutaneous manifestations.

However, the typical clinical, serologic and radiologic findings in our patient were consistent with RA and she had no evidence of classic signs of psoriatic arthritis, such as distal interphalangeal joint involvement, dactylitis or new bone formation.

A second reason for the induction of psoriasis in our patient could be that the skin lesions represented an allergic reaction to abatacept.

However, a close temporal association between the initiation of abatacept and the onset of the skin lesions was not evident, therefore precluding an early allergic reaction. In addition, the biopsy results ruled out a type IV immune reaction.

Current paradigm indicates that psoriasis is driven by T cell mediated immune response targeting keratinocytes. A third reason why our patient developed psoriasis during abatacept therapy could be that the pathophysiology of psoriasis may not be explained solely on the basis of T cell activation. Intrinsic alterations in epidermal keratinocytes may play a very relevant role in disease expression.8

Although TNFα antagonists are effective in the treatment of refractory psoriasis, some cases have indicated that psoriasis might be induced as a result of treatment. Preliminary data suggest that the development of psoriasiform lesions in previously unaffected individuals represents an adverse effect of anti-TNFα treatment, which is supposed to be a class effect rather than a drug specific effect.9 Our patient had received TNFα blocking therapy previously. But as the skin lesions occurred almost 2 years after the discontinuation of TNFα blocking therapy, an association between anti-TNFα treatment and the onset of psoriasis seems highly unlikely.

In conclusion, we present a patient with RA who developed psoriasis following treatment with abatacept. We suggest a causal connection between drug exposure and the development of psoriasis, as the skin lesions subsided after discontinuation of treatment and reoccurred after re-exposure to the drug. Further exploration is warranted in additional studies to elucidate the impact of T lymphocyte costimulation and the role of keratinocytes in the pathophysiology of psoriasis.

LEARNING POINTS

In this patient psoriasis might have been evoked by abatacept.

As abatacept is relatively new, its spectrum of side effects may not be completely known yet.

The conundrum that an anti-inflammatory biological agent leads to the manifestation of psoriasis might apply not only to TNF blockers but to costimulation blockade as well.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Genovese MC, Schiff MM, Luggen M, et al. Efficacy and safety of the selective co-stimulation modulator abatacept following two years of treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to anti-TNF therapy. Ann Rheum Dis 2008; 67: 547–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weisman MH. J Rheumatol 2006; 33: 2162–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kremer JM, Dougados M, Emery P, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with the selective costimulation modulator abatacept: twelve months results of a phase IIb, double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52: 2263–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schön MP, Boehnke WH. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 1899–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lebwohl M. Psoriasis. Lancet 2003; 361: 1197–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abrams JR, Kelley SL, Hayes E, et al. Blockade of T lymphocyte costimulation with cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4-immunoglobulin (CTLA4Ig) reverses the cellular pathology of psoriatic plaques, including the activation of keratinocytes, dendritic cells, and endothelial cells. J Exp Med 2000; 192: 681–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abrams JR, Lebwohl MG, Guzzo CA, et al. CTLA4Ig-mediated blockade of T-cell costimulation in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. J Clin Invest 1999; 103: 1243–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albanesi C, De Pita’ O, Girolomoni G. Resident skin cells in psoriasis: a special look at the pathogenetic functions of keratinocytes. Clin Dermatol 2007; 25:581–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The enigmatic development of psoriasis and psoriasiform lesions during anti-TNF therapy: a review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2008; 37: 251–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]