Abstract

A 65-year-old patient presented with isolated bilateral third nerve palsy. Neuroimaging demonstrated a 2 cm pituitary mass with extension into the cavernous sinus on the right. The patient went on to experience spontaneous complete resolution of symptoms with associated radiological shrinkage of the mass. Bilateral third nerve palsy is a very rare presenting sign, with only one previous case reported in the literature secondary to a pituitary adenoma. Spontaneous resolution of non-functioning pituitary tumours is reported to occur in approximately 10% of cases. However, there are only a small number of reports to date involving spontaneous regression of tumours with corresponding resolution of cranial nerve palsies.

Background

Unilateral third nerve palsies are a relatively common occurrence, and represent a well known presenting sign of a posterior communicating artery aneurysm, herpes zoster ophthalmicus, temporal arteritis, and migraine. Unilateral third nerve palsies have also been demonstrated to be secondary to pituitary adenomas.1 However, reports of bilateral third nerve palsies in the literature are very rare. A review of the literature revealed only one case report of isolated bilateral third nerve palsy caused by pituitary apoplexy.2 However, this was not an intermittent palsy as in the case we present here. We report to the best of our knowledge the first case of spontaneously resolving isolated bilateral third nerve palsy secondary to a pituitary mass, with corresponding radiological evidence of regression.

Case presentation

A 65-year-old woman presented with a history of headache and double vision for 3 days. In addition to this, her husband had noted drooping of her right eyelid. Further questioning revealed a subacute evolution of worsening ophthalmoplegia with oblique/diagonal diplopia, associated with mild headache over the crown of her head. She had a past medical history of hypertension and had been commenced on indapamide and atenolol. She was otherwise in good health. There was no history of hypothyroidism. On examination, she looked generally well. She had partial left ptosis with a dilated left pupil that was sluggish to respond to light. The right eye was in the downward abducted position but with a full range of movement. Fundoscopy revealed grade II hypertensive retinopathy with no papilloedema. Visual fields were preserved on confrontation testing. Trochlear and abducens nerves were found to be intact on testing as demonstrated by full range of abduction bilaterally and without excyclotortion on downward gaze. There was normal facial sensation, full strength of the muscles of mastication, and intact corneal reflexes.

Investigations

Routine blood tests showed a normal full blood count, urea and electrolytes, with a C reactive protein (CRP) value <3 mg/l. Pituitary hormone profile revealed: prolactin 159 mIU/l (normal range (NR) 40–530), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) 0.09 mU/l (NR 0.2–5.0), thyroxine (T4) 12 pmol/l (NR 10–24), luteinising hormone (LH) 2.0 IU/l (NR 11–40), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) 5.8 IU/l (NR 22–153), cortisol 361 nmol/l (NR 138–690), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) 10 ng/l (NR 10–50), growth hormone 0.34 μg/l, and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) 8 nmol/l (NR 6–30). These results led to a clinical diagnosis of non-functioning pituitary adenoma with some evidence of hypopituitarism. Formal visual field testing was arranged and was reported as borderline normal.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the patients head was done and this revealed a small pituitary mass encroaching on the right cavernous sinus (fig 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showed a 2 cm pituitary mass with expansion of the pituitary fossa extending into the cavernous sinus particularly on the right (fig 2). There was slight upward displacement of the optic chiasm. Although the signal characteristics were a little unusual, it was thought most likely to represent a pituitary adenoma. The appearances were not convincing of haemorrhage.

Figure 1.

Plain computed tomography scan showing a small pituitary mass encroaching on the right cavernous sinus.

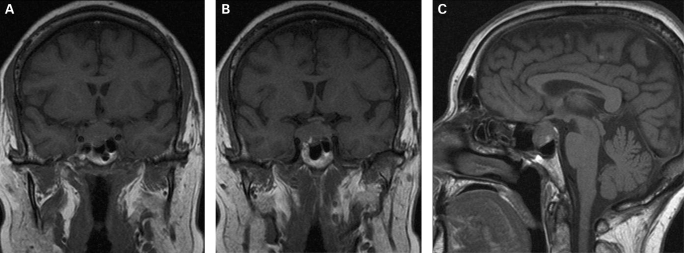

Figure 2.

(A) Coronal T1 weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showing a pituitary mass with expansion of the pituitary fossa. (B) Coronal T1 weighted MRI scan showing a pituitary mass extending into the cavernous sinus, particularly on the right. (C) Saggital T1 weighted MRI scan of the pituitary tumour.

Differential diagnosis

The most likely cause of a pituitary mass is an adenoma. However, a number of other sellar lesions may mimic pituitary adenomas, and the differential diagnosis includes lymphocytic infiltration, germinomas, craniopharyngomas, meningiomas and sarcoidosis.3

Outcome and follow-up

By the third day of admission the patient’s headache had spontaneously resolved and there was no longer any clinically detectable third nerve palsy on the left. A mild ptosis on the right persisted. Furthermore, on review during the fourth day of admission, the diplopia had completely resolved and there was no visible ptosis on the right.

The patient was transferred to the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London where she underwent repeat MRI brain, which showed a decrease in the size of the known suprasellar extension and improvement in the right cavernous sinus (fig 3). She had complete resolution of her symptoms. Repeat pituitary profile showed cortisol 821 nmol/l (NR 138–690), with the rest of the pituitary profile normal. She was discharged home with a view to undergoing a repeat MRI in 3 months.

Figure 3.

(A) Coronal T1 weighted MRI scan showing decrease in size of the known suprasellar extension and improvement in the right cavernous sinus. (B) Saggital T1 weighted MRI scan showing decrease in size of the pituitary mass.

Discussion

Clinically and radiologically we suspect the pituitary mass presented in this case most likely represents apoplexy or infarction of a non-functional pituitary adenoma. In autopsy series, 46% of macroadenomas were found to be non-functioning, with the majority of the rest being mainly hormonal active adenomas,4 making this the most likely diagnosis in the absence of hormone overproduction. Furthermore MRI study can, with adequate accuracy, distinguish between pituitary adenoma and hyperplasia,5 or craniopharyngoma.6

One of the unusual features of this case is that the patient presented with isolated bilateral nerve palsy. Bilateral third nerve palsy is a very rare presenting sign for which only a small number of case reports exist in the literature. From these it can be established that the differential diagnosis includes ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm,7 trauma,8 malignancy,9 Guillian–Barré syndrome,10 and multiple sclerosis.11 There are even rare reports of this presentation being associated with benign intracranial hypertension,12 temporal arteritis,13 diabetes,14 and sarcoidosis.15

The most common ophthalmic presentation of pituitary tumours is with visual field defects secondary to compression of the optic chiasm. Although oculomotor palsies may occur in isolation, they are usually combined with loss of vision or visual field and develop as the end stage of a pituitary tumour.16 There have been several cases of bilateral third nerve palsy occurring in association with fourth and sixth nerve palsies.17 However, to date there has been only one case report of isolated bilateral oculomotor nerve palsy as the presenting sign in a patient with pituitary apoplexy.2

The other unusual feature of this case was the spontaneous regression of the pituitary mass, with associated complete resolution of the patient’s symptoms. In a review of the literature regarding the natural course of incidentally discovered non-functioning pituitary tumours, it was found that 34 out of 304 (11%) of patients experienced spontaneous regression of tumour volume over long term follow-up.18 All of these cases were either asymptomatic or associated with visual field defects only. In no case of spontaneous regression was cranial nerve palsy reported. It was proposed that the observed regression may occur secondary to clinically silent ischaemia of the tumour, on the basis that symptomatic pituitary apoplexy has been found to occur in 10% of non-functioning macroadenomas.19

There are, however, several cases of intermittent isolated unilateral third nerve palsies in association with pituitary tumours reported in the literature. In one of these cases the patient presented with a painful third nerve palsy which spontaneously resolved during the course of a week, only to recur within a month. She was eventually diagnosed with a prolactinoma.20 In a second case a patient was found to experience intermittent painful third nerve palsy occurring two to three times weekly over a course of 4 months. Eventually the palsy became complete and permanent, without subsequent recovery. Histology of the pituitary mass revealed a pituitary acidophilic adenoma without immunohistochemical activity to prolactin, growth hormone or ACTH.20 Finally, transient partial oculomotor nerve palsy has been reported in association with a pituitary macroadenoma in the early postpartum period.21

Learning points

Pituitary tumour should be included in the differential diagnosis of a patient presenting with isolated bilateral third nerve palsy, or with a history of intermittent diplopia.

Intermittent isolated third nerve palsies may be a presenting sign of pituitary adenomas.

Spontaneous regression of pituitary tumours is observed and may occur secondary to tumour ischaemia.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication

REFERENCES

- 1.Kim SH, Lee KC, Kim SH. Cranial nerve palsies accompanying pituitary tumour. J Clin Neurosci 2007; 14: 1158–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lau KK, Joshi SM, Ellamushi H, et al. Isolated bilateral oculomotor nerve palsy in pituitary apoplexy: case report and review. Br J Neurosurg 2007; 21: 399–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Post KD, McCormick PC, Bello JA. Differential diagnosis of pituitary tumours. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1987; 16: 609–45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomita T, Gates E. Pituitary adenomas and granular cell tumors. Incidence, cell type, and location of tumor in 100 pituitary glands at autopsy. American Journal of Clinical Pathology 1999; 111(6): 817–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chanson P, Daujat F, Young J, et al. Normal pituitary hypertrophy as a frequent cause of pituitary incidentaloma: a follow–up study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001; 86: 3009–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsuda M, Takahashi S, Higano S, et al. CT and MR imaging of craniopharyngioma. Eur Radiol 1997; 7: 464–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coyne TJ, Wallace MC. Bilateral third cranial nerve palsies in association with a ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm. Surg Neurol 1994; 42: 52–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tognetti F, Godano U, Galassi E. Bilateral traumatic third nerve palsy. Surg Neur 1988; 29: 120–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAvoy CE, Kamalarajab S, Best R, et al. Bilateral third and unilateral sixth nerve palsies as early presenting signs of metastatic prostatic carcinoma. Eye 2002; 16: 749–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Georgiou T, McKibbin M, Doran RM, et al. Bilateral third–nerve palsy with aberrant regeneration in Guillain–Barré syndrome. Eye 2003; 17: 254–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Seze J, Vukusic S, Viallet-Marcel M, et al. Unusual ocular motor findings in multiple sclerosis. J Neurolog Sci 2006; 243: 91–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thapa R, Mukherjee S. Transient bilateral oculomotor palsy in pseudotumor cerebri. J Child Neurol 2008; 23: 580–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lazaridis C, Torabi A, Cannon S. Bilateral third nerve palsy and temporal arteritis. Arch Neurol 2005; 62: 1766–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chauhan S, Sachdev A, Bali J, et al. Simultaneous bilateral oculomotor nerve paralysis: an unusual manifestation of diabetes mellitus. Singapore Med J 2006; 47: 1006–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Velazquez A, Okun MS, Bhatti MT. Bilateral third nerve palsy as the presenting sign of systemic sarcoidosis. Can J Ophthalmol 2001; 36: 416–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy A. Pituitary disease: presentation, diagnosis and management. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004; 75(Suppl 3): S47–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keane JR. Acute bilateral ophthalmoplegia: 60 cases. Neurology 1986; 36: 279–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dekkers OM, Pereira AM, Romijn JA. Treatment and follow-up of clinically non-functioning pituitary macroadenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: 3717–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arita K, Tominaga A, Sugiyama K, et al. Natural course of incidentally found nonfunctioning pituitary adenoma, with special reference to pituitary apoplexy during follow-up examination. J Neurosurg 2006; 104: 884–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wykes WN. Prolactinoma presenting with intermittent third nerve palsy. Br J Ophthalmol 1986; 70: 706–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cano M, Lainez JM, Escudero J, et al. Pituitary adenoma presenting as painful intermittent third nerve palsy. Headache 1989; 29: 451–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]