Abstract

Attention problems form one of the core characteristics of Attention-Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD), a multifactorial neurodevelopmental disorder. From twin research it is clear that genes play a considerable role in the etiology and in the stability of ADHD in childhood. Association studies have focused on genes involved in the dopaminergic and serotoninergic systems, but with inconclusive results. This study investigated the effect of 26 Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes encoding for serotonin receptors 2A (HTR2A), Catechol-O-Methyltransferase (COMT), Tryptophane Hydroxylase type 2 (TPH2), and Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF). Attention problems (AP) were assessed by parental report at ages 3, 7, 10, and 12 years in more than 16,000 twin pairs. There were 1148 genotyped children with AP data. We developed a longitudinal framework to test the genetic association effect. Based on all phenotypic data, a longitudinal model was formulated with one latent factor loading on all AP measures over time. The broad heritability for the AP latent factor was 82%, and the latent factor explained around 55% of the total phenotypic variance. The association of SNPs with AP was then modeled at the level of this factor. None of the SNPs showed a significant association with AP. The lowest p-value was found for the rs6265 SNP in the BDNF gene (p = 0.035). Overall, our results suggest no evidence for a role of these genes in childhood AP.

Keywords: Attention problems, Genetics, Candidate genes

Introduction

Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder starting early in childhood. Core characteristics are attention deficits, hyperactivity and impulsivity. Twin, family and adoption studies suggest that ADHD is one of the most heritable psychiatric disorders. A mean estimate of the heritability of ADHD is 76% both in children and adults (Biederman and Faraone 2005; Faraone et al. 2005; Derks et al. 2009).

Many candidate association studies for ADHD have been conducted. Candidate gene studies with a focus on the dopaminergic system showed most consistent results, but the genes accounted only for a small part to the genetic variation of ADHD. Candidate genes involving into the serotonergic and noradrenergic systems are also widely investigated, but their contribution in the etiology of ADHD is not conclusive (for reviews see: Banaschewski et al. 2010; Gizer et al. 2009; Franke et al. 2009). One of the reasons for the lack of success of candidate genes studies, may be the heterogeneity and complexity of ADHD (Hudziak 2001; Steinhausen 2009). Furthermore, it is likely that a large number of different genes are implicated in the etiology of ADHD, each with a small genetic effect. Most studies lacked the power to detect the small effects of these genes (Bergen et al. 2010). Therefore genetic association studies need strategies that help to increase the statistical power (Faraone et al. 2005; Neale et al. 2008).

One strategy to increase power is by using a longitudinal design (Hottenga and Boomsma 2007). Such design may be especially useful for stable characteristics for which the same genes are implicated. Recently, Middeldorp et al. (2010) developed a longitudinal design for genetic association analyses on depression and anxiety. The effect of SNPs was tested on a latent factor expressing the shared variance across time points spanning more than 10 years. The heritability estimate for the anxiety/depression latent factor was higher than the heritability estimates for the anxiety/depression measures at each age separately. As such, more power to detect associations is achieved (Medland and Neale 2010; Minica et al. 2010). A power analysis revealed that by applying this longitudinal approach it is possible to detect effects explaining 1.4% to 3.6% of the variance with a power of 80%. This was considerably higher than for univariate models tested in samples of equal size.

In the present study we test the association between genes and Attention Problems (AP). Attention Problems were measured with the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach 1991, 1992) and used as index for ADHD. Derks et al. (2008) showed that the genetic overlap between the CBCL AP scale and the DSM-IV diagnosis of ADHD is high. They reported genetic correlations ranging between 0.52 and 0.68.

The choice of the candidates genes was based on the availability of a genotype dataset consisting of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from a study of Middeldorp et al. (2010). From this set we selected candidate genes with a possible impact on the etiology of AP as reported in the literature (Banaschewski et al. 2010; Gizer et al. 2009; Franke et al. 2009). SNPs were available for genes involved in coding of the 2A serotonin receptor (HTR2A), tryptophane hydroxylase (TPH2), Catechol-O-Methultransferase (COMT), and neurogenenis: Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF). HTR2A and TPH2 are were involved in the serotoninergic system, which is mentioned as possible pathway in the etiology of ADHD because of its relation with impulsive-aggressive behaviors in children (Gizer et al. 2009; Halperin et al. 1997). There is evidence that HTR2A has a moderating role on dopamine activity and hyperlocomotion after amphetamine administration (O’Neill et al. 1999). Also TPH2 may play a role in dopamine activity, since it is involved in the production of serotonin (Walther et al. 2003). One SNP was available for COMT, a gene involved in the regulation of synaptic dopamine in the frontal cortex. Since both frontal cortical dysfunction and abnormalities in the dopaminergic system have been related to ADHD (Genro et al. 2010), the COMT gene may be a good candidate. SNPs for BDNF were included because of its role in neuronal plasticity and neurogenesis (Tsai 2007). Evidence for a role of BDNF came from pharmacological studies, were it was found that commonly used drugs for ADHD treatment modulate the expression of BDNF (Meredith et al. 2002). In addition, heterozygous BDNF knockout mice display symptoms related to ADHD (Linnarsson et al. 1997).

To test for the genetic associations we apply the longitudinal method as developed by Middeldorp et al. (2010). In a cohort of over 16,000 twin pairs, we first modeled longitudinal data collected at ages 3, 7, 10 and 12 year, with a latent factor model to explain the covariance between measures at all ages. In a subsample of 1148 children with genotype data, the effect of the SNPs on AP was tested. To make use of all available data, the effect of the SNPs was modeled on the common latent factor.

Methods

Participants

The study is part of an ongoing longitudinal twin study in the Netherlands. The twins were registered with the Netherlands Twin Registry (NTR) shortly after birth by their parents (Bartels et al. 2007; Boomsma et al. 2006). During the first 12 years of their lives the parents received surveys with items on behavioral and emotional development about every 2 years. The present study included data collected at ages 3, 7, 10 and 12 years. Reports by both father and mother were included in the current study.

Random subsamples of the young twins were also invited to participate in experimental and laboratory studies (for example, the studies of genetics of cognition, attention and brain function) and provide a DNA sample (Boomsma et al. 2006). Genotyping data were obtained for 1,148 children from 593 families and included 569 boys and 579 girls who also had at least one AP score. As this sample included 305 monozygotic male (MZM) twins (150 complete pairs) and 343 monozygotic female (MZF) twins (169 complete pairs), there were 419 (569 − 150) unique male and 410 (579 − 169) unique female genotypes.

Longitudinal modeling was done first in the total sample consisting of twins from 16,169 families, who participated at least once, including 2,436 MZM, 2,856 DZM, 2,742 MZF, 2,556 DZF, 2,576 and 5602 dizygotic opposite sex (DOS) twin pairs.

We tested whether the genotyped subsample differed from the total sample regarding sex, clinical range, birth country parents, and Social Economic Status (SES). With a percentage of 50% boys in the total sample and with 49.6% boys in the genotyped samples, the sex distribution did not differ between the 2 samples (χ2(1) = 0.076, p = 0.783). The percentages of children falling within the clinical range (calculated as T-score of CBCL AP ≥67) were 4% and 4.6% (age 3), 5.4% and 4.4% (age 7), 5.0 and 3.8% (age 10), 5.7% and 5.3% (age 12) for respectively the total and the genotyped sample. The percentages did not differ between the 2 samples (age 3: χ2(1) = 1.02, p = 0.296; age 7: χ2(1) = 2.201, p = 0.138; age 10: χ2(1) = 2.87, p = 0.09; age 12: χ2(1) = 0.21, p = 0.649). In the total and the genotyped sample of twins, the majority of parents were born in Netherlands (93.1 and 92.9%) or in a western country (3.2 and 2.9%). In the other families (3.7 and 4.2%) at least one parent was born in a non-western country. These percentages were not different between the two samples (χ2(2) = 0.632; p = 0.729). Information about SES was obtained from surveys completed by parents and categorized into 3 SES groups. For the total and the genotyped sample the percentage were 22.4 and 21.6% low SES, 45.1 and 41.9% middle SES and 32.3 and 36.4% high SES. These percentages did not differ between the two samples (χ2(2) = 4.438, p = 0.109).

Measures

AP is measured with the CBCL, a standardized questionnaire for parents to report specific behavioral, emotional, and social problems (Achenbach 1991, 1992). The questionnaire used at age 3 years consisted of 100 items (CBCL/2-3) and the questionnaire used for the 7, 10 and 12-years-old twins consist of 120 items (CBCL/4-18). Parents were asked to rate the behavior that the child displayed currently or in the past 2 months on a 3-point scale: 0 if the problem item was not true, 1 if the item was somewhat or sometimes true, and 2 if it was very true or often true. As measure for AP at age 3 we used the Overactive scale, which is based on factor analyses of data from several Dutch population samples (Koot et al. 1997). The Overactive scale derived from the CBCL/2-3 contains 5 items. The AP scale derived from the CBCL/4-18 contains 11 items (Verhulst et al. 1996). The raw sum scores of the items of the Overactive and AP scale were used in the analyses. In order to obtain a distribution that approaches normality with respect to skewness and kurtosis, normal scores were computed using PRELIS (Jöreskog and Sörbom 1986).

Genotyping

Table 1 shows the set with genotyped SNPs. The set of SNPs was obtained from a previous study examining the relation between these SNPs and anxiety/depression (Middeldorp et al. 2010). In the present study, SNPs of the HTR2A, COMT, TPH2, and BDNF genes were included. Tagging SNPs, were selected for BDNF and TPH2 in order to capture most of the variation in these genes. Tagging SNPs for BDNF and TPH2, were selected from HapMap Public Release #19, applying the efficient multimarker method with r 2 > 0.8, and minor allele frequency (MAF) >0.05 as implemented in the HapMap web browsers (http://www.hapmap.org) (de Bakker et al. 2005). For the genomic region of the BDNF gene, we captured 38 out of 53 (71%) alleles at r 2 > 0.8. For the TPH2 gene we captured 108 out of 148 (72%) alleles at r 2 > 0.8.

Table 1.

The genotyped SNPs per gene, minor allele frequency (MAF), the results of the Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) test in the total sample and the effect of the SNPs (β)

| Genes | SNPs | MAF | p-value HWE | β | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDNF | rs2049048 | A<G | 15.6 | Ns | 0.03 |

| rs7103873 | C<G | 45.1 | Ns | 0.09 | |

| rs6265 | T<C | 22.4 | Ns | −0.14* | |

| rs11030107 | G<A | 24.8 | Ns | −0.01 | |

| rs11030123 | A<G | 9.2 | Ns | 0.01 | |

| rs1491851 | T<C | 40.6 | Ns | 0.06 | |

| rs17309930 | A<C | 17.6 | Ns | −0.09 | |

| rs7124442 | C<T | 31.6 | Ns | −0.01 | |

| COMT | rs4680 | G<A | 43.8 | Ns | −0.02 |

| HTR2A | rs6311 | T<C | 42.0 | Ns | −0.04 |

| rs6314 | A<G | 8.6 | Ns | 0.07 | |

| rs6313 | A<G | 44.1 | 0.008 | −0.05 | |

| TPH2 | rs1007023 | G<T | 14.9 | Ns | 0.07 |

| rs10748190 | G<A | 42.0 | Ns | −0.02 | |

| rs12231356 | T<C | 7.3 | Ns | −0.09 | |

| rs1352251 | C<T | 43.2 | Ns | −0.03 | |

| rs1473473 | C<T | 16.1 | 0.00005 | 0.06 | |

| rs2129575 | T<G | 25.4 | Ns | 0.001 | |

| rs2171363 | A<G | 44.4 | Ns | −0.04 | |

| rs3903502 | T<C | 41.7 | Ns | −0.02 | |

| rs4474484 | A<G | 36.9 | Ns | −0.01 | |

| rs4760820 | G<C | 41.6 | Ns | 0.06 | |

| rs7305115 | A<G | 44.2 | Ns | −0.04 | |

| rs10748185 | A<G | 48.7 | Ns | 0.04 | |

| rs17110489 | C<T | 26.5 | Ns | −0.04 | |

| rs7300641 | T<G | 17.7 | Ns | 0.04 |

Asterisks for β’s indicate to p-value <0.05

ns nonsignificant

Multiplex genotyping assays were designed using the Sequenom MassARRAY Assay Design software Version 3.1 and performed with MassARRAY iPLEX (Sequenom Inc, San Diego, CA). Amplification reactions were based on the manufacturer’s instructions with a modified protocol (Macgregor et al. 2008). Genotypes were assigned by using Typer Analyzer version 4.0 software (Sequenom, San Diego, CA). If there were disagreements or unclear positioned dots produced by Typer Analyzer 4.0 or more than 50% of the SNPs failed in a well, the SNPs were excluded from analysis.

The set of SNPs was obtained from a dataset that included two samples: one with children (twins) and one with adult data (twins, parents, and sibs). Genotyping error checks were performed in the dataset including both samples using Pedstats (see Middeldorp et al. 2010). If the Mendelian inheritance was inconsistent, the individuals’ genotypes were set to unknown. After these corrections, missingness per SNP was calculated. It appeared that genotyping was successful in more than 98% of the subjects for all SNPs with the exception of TPH2 rs1352251 (2.5% missing), COMT rs4680 (6.4% missing) and HTR2A rs6311 (17.9% missing). For these three SNPs, we checked whether the genotypes differed in a subsample of subjects (N = 282) who were genotyped for the same SNPs in another lab with an independent method (Sullivan et al. 2009). Since this was not the case, we decided to analyze these SNPs as well. Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium was tested in Haploview (Wigginton et al. 2005; Barrett et al. 2005) resulting in 2 SNPs with a p-value below 0.01 (Table 1). These 2 SNPs were still included in the analyses so that consistencies in results, for example more SNPs in one gene showing a significant result, were not overlooked.

Statistical methods

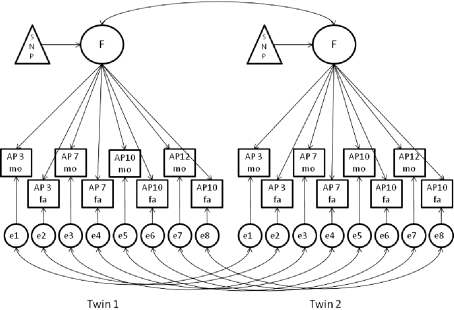

Figure 1 shows the longitudinal model used to test the effect of the SNPs on AP (Medland and Neale 2010; Middeldorp et al. 2010). In the model one latent factor (F, represented by a circle) influences on all observed AP measures (represented by squares), explaining the shared variance across ages and raters. From now on, we refer to the latent factor as the AP factor. The variance of the AP factor was constrained at 1. As AP measures within a twin pair are not independent, the latent factors were correlated between twins allowing different correlations for MZ and DZ pairs. In Fig. 1, the arrow between the latent AP factors reflects this twin correlation. In this figure, the latent factors e1 to e8 denote unique factors that account for the residual variances of the observed variables. Genetic epidemiological analyses have shown that genetic factors are not entirely the same over the ages 3–12 (Rietveld et al. 2003, 2004). To allow for age-dependent familial effects, twin correlations were estimated for the unique factors. These correlations also are allowed to differ for MZ and DZ twin pairs. The factor loadings for the common and unique factors, and the familial correlations were equal for boys and girls. Sex was included as covariate on the means of the observed variables (not shown in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Factorial association model. The latent AP factor loads on the longitudinal AP measures (4 maternal (mo) and 4 paternal (fa) at age 3, 7, 10 and 12), reflecting the stability across time and across raters. The effect of the SNP is modeled on the AP means through the AP factor. The arrow between the latent factors reflects the twin correlation. The latent factors e1 to e8 denote unique factors that account for the residual variances of the observed variables (squares). The arrows between the unique factors reflect the twin correlations that allow for age-dependent familial effects. The correlations differ for MZ and DZ twin pairs. Not shown in the Figure (for the sake of clarity), but included in the model: the variance of the AP factor, which is constrained to 1 and the effect of sex on the means

As first step, the model was applied in the total data set to obtain the best possible estimates for the factor loadings for the common and unique factors and the twin correlations for the unique factors. By using all available phenotypic data, more reliable estimates were obtained. Secondly, the effect of the SNPs was tested in the genotyped subsample. In this model the factor loadings for the common and unique factors, and the twin correlations between the unique factors were constrained at the estimates obtained in the first step (see Table 4). The effect of the SNPs was modeled on the AP mean through the AP latent factor (see triangle Fig. 1) and was equal for boys and girls. The equation for AP measured in twins at age 7 become: AP = μ + β1 * sex + β2 * fage7f * SNP, in which fage7f is the factor loading from the AP factor on AP measured at age 7 rated by father, β2 is the coefficient for the SNP effect on the AP mean and β1 is the coefficient for a sex effect on the AP mean. The SNP genotype is coded as 0, 1 or 2 reflecting the number of minor alleles. The AP factor correlations between twins were freely estimated, because these vary as a function of the effect of the SNP on the latent factor.

Table 4.

Factor loadings for common and unique factors and the MZ and DZ correlations (rMZ and rDZ) for the unique factors of the model in the total sample

| Age | Rater | Factor loading | Residual SD | rMZ | rDZ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Mother | 1.2337 | 1.7753 | 0.6465 | 0.1539 |

| Father | 1.2310 | 1.7186 | 0.6334 | 0.1807 | |

| 7 | Mother | 2.3359 | 1.8036 | 0.5994 | 0.3254 |

| Father | 2.0936 | 1.7091 | 0.6365 | 0.3872 | |

| 10 | Mother | 2.5046 | 1.7403 | 0.5652 | 0.3108 |

| Father | 2.2797 | 1.6928 | 0.6110 | 0.3767 | |

| 12 | Mother | 2.3230 | 1.7810 | 0.6231 | 0.3063 |

| Father | 2.1039 | 1.7563 | 0.6472 | 0.4104 |

Standard software for genetic association analyses is not well equipped for such complex models including both family and longitudinal data. Therefore, analyses were performed in Mx, a software program designed for structural equation (Neale et al. 1999). To use all data, analyses were performed on raw data using the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) method.

For the association effect P-values below 0.05 are reported. Because multiple testing will increase the probability of obtaining false-positive associations, a statistical adjustment of the α-level is needed to keep the type I error at 5%. Applying a Bonferroni correction would be too conservative for SNPs in linkage disequilibrium (LD) (Nyholt 2004). Therefore, the method as described by Nyholt (2004) was applied. This method estimates the number of independent SNPs tests for a given gene (see: http://gump.qimr.edu.au/general/daleN/SNPSpD/). Subsequently, this number (in most cases this number is less than the number of SNPs) is used in the Bonferroni correction. This method revealed an α-level of 0.0072, 0.018, and 0.0046 for respectively the BDNF gene, HTR2a gene, and TPH2 gene. For the COMT gene there is only one SNP and no correction is required.

Results

Means and factor analysis

The means and standard deviations for AP across ages and raters are presented in Table 2. The AP means of the genotyped sample were not different from the AP means of the total sample of twins. For all ages, both fathers and mothers reported more AP in boys than in girls. In the total sample about 50% of the twin pairs had data on more than one age. In the genotyped sample, for 86% of the twins AP data were available for more than one age. Table 3 displays the phenotypic stability coefficients across ages. The stability coefficients ranged from 0.27 to 0.69 and did not differ between girls and boys (∆χ(10)² = 16.33, p = 0.091). The stability was lowest between age 3 and 12, and increases with shorter time intervals. Correlations between paternal and maternal were between 0.60 and 0.72 and were rather similar across ages.

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviation (SD) for AP scores at age 3, 7, 10 and 12 in the total sample and in the genotyped sample

| Total sample | Genotyped sample | F | p | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | ||||||||||||

| Valid N | Mean | SD | Valid N | Mean | SD | Valid N | Mean | SD | Valid N | Mean | SD | ||||

| Age 3 | Mo | 14331 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 14386 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 537 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 545 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 2.28 | 0.13 |

| Fa | 9418 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 9448 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 370 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 363 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 2.06 | 0.15 | |

| Age 7 | Mo | 8461 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 8645 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 495 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 519 | 2.5 | 2.7 | <1 | 0.92 |

| Fa | 6132 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 6193 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 414 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 448 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.91 | 0.09 | |

| Age 10 | Mo | 5332 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 5698 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 501 | 3.5 | 2.9 | 505 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 1.09 | 0.30 |

| Fa | 3782 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 4013 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 410 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 402 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 1.95 | 0.16 | |

| Age 12 | Mo | 3495 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 3668 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 453 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 483 | 2.3 | 2.7 | <1 | 0.64 |

| Fa | 2535 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2679 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 371 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 398 | 1.9 | 2.5 | <1 | 0.48 | |

In the last 2 columns the statistics for the comparison of AP scores between total and genotyped sample

Table 3.

Correlations between the maternal (Mo), paternal (Fa) reports of AP at ages 3, 7, 10, and 12 years and their cross-time correlations

| Age 3 | Age 7 | Age 10 | Age 12 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls | |||||||||

| Boys | Mo | Fa | Mo | Fa | Mo | Fa | Mo | Fa | |

| Age 3 | Mo | – | 0.62 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.30 |

| Fa | 0.63 | – | 0.34 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.31 | |

| Age 7 | Mo | 0.41 | 0.32 | – | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.55 | 0.57 | 0.49 |

| Fa | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.72 | – | 0.53 | 0.62 | 0.47 | 0.55 | |

| Age 10 | Mo | 0.38 | 0.30 | 0.66 | 0.57 | – | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.57 |

| Fa | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.57 | 0.63 | 0.71 | – | 0.55 | 0.65 | |

| Age 12 | Mo | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.72 | 0.62 | – | 0.66 |

| Fa | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.51 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.69 | 0.72 | – | |

Below diagonal: boys, above diagonal: girls

The factor loadings, the residual variances, and the twin correlations for the residual variances of the model in the total sample are given in Table 4. The AP factor explained 33, 64, 68 and 63% of the variance in maternal ratings, and 34, 61, 65 and 59% in paternal ratings at ages 3, 7, 10, and 12 years. The MZ correlations for the latent AP factor was 0.82 and for 0.27 for DZ twins. A genetic twin analysis of the AP factor revealed a broad heritability (dominance and additive estimates) of 82%, which is slightly higher than the heritability estimates reported for each age (ranging from 68 to 76%) (Rietveld et al. 2003).

Association analyses

We performed the genetic association analyses in the total sample. To be sure we did not overlook sex differences in gene effects, we tested for sex differences by also estimating SNP effects separately by sex and then constraining the coefficient for the SNP effect to be equal for boys and girls. No significant results were obtained for these tests (uncorrected p-values ranged from 0.061 and 0.977). The results of the association analyses for the whole sample are shown in Table 1. No significant results were obtained for any of the SNPs. The lowest p-value was found for the SNP rs6265 (β = −0.14; p = 0.035). When we take multiple testing into account this effect is not significant. The SNP is known as the Val66Met polymorphism in the BDNF gene. The ‘T’ (Met) allele was associated with a lower score on the AP factor.

Discussion

We investigated the association between childhood AP and SNPs in the serotonergic, dopaminergic system and the BDNF gene. To increase the statistical power, the effect of SNPs was tested on a latent factor that represents the stability of AP across childhood. Power calculations reported in Middeldorp et al. (2010) showed that this method could detect effects explaining 3% of the variance with a power of 80%. Genetic analysis of the latent AP factor revealed a heritability of 82%, which is slightly higher than the heritabilities at the separate ages. Despite the adequate statistical power, our findings do not support an influence of any of the SNPs on AP.

The largest effect was found for the SNP rs6265 (p = 0.035). The rs6265 polymorphism is also known as the Val66Met polymorphism and is the most reported SNP in the BDNF gene. In the present study the Met (T) allele carriers of the Val66MET polymorphism had decreased AP levels. This implies that the carriers with the more common Val allele had higher AP levels. In this respect, our results agree with the 2 studies that reported an association between ADHD and Val66Met with the Val allele as the risk allele (Kent et al. 2005; Lanktree et al. 2008). However, in literature studies with negative results (Schimmelmann et al. 2007; Lee et al. 2007, Xu et al. 2007; Conner et al. 2008) seem to outnumber the studies with positive results. In addition, recent meta-analyses do not support the association between Val66Met polymorphism and ADHD (Sanchez-Mora et al. 2010; Forero et al. 2009). Also the results of the genome wide association studies (GWAS) for ADHD do not indicate a role for the BDNF gene in ADHD (Lasky-Su et al. 2008; Neale et al. 2008). In sum, the present study found a marginally significance for the Val66Met SNP, but in the light of the negative results in previous research the result being due to chance cannot be ruled out.

For the dopaminergic system only the Val158Met polymorphism of the COMT gene was available. It is the most studied SNP for this gene and it consists of a G to A mutation, which leads to substitution of Met for Val in enzyme synthesis. The Val (G) allele encodes a higher activity of COMT, which leads to a reduction of intra synaptic dopamine (Lachman et al. 1996). In agreement with the results of two meta analyses of COMT (Cheuk and Wong 2006; Gizer et al. 2009), we did not find a significant association between COMT and AP. Previous research showed that the relation between COMT and AP is complex. Some studies reported an ADHD association of the Val allele of the COMT gene (Eisenberg et al. 1999; Albaugh et al. 2010), while others reported a relation between the Met allele and ADHD (Biederman et al. 2008; DeYoung et al. 2010). In addition, the Val allele has been associated with anti-social behaviors in children with ADHD (Thapar et al. 2005), but not in children without ADHD (Caspi et al. 2008). Thus, the results for COMT and ADHD seems not to be consistent, which may be inherent on the complexity of ADHD: A phenotype with a large phenotypic heterogeneity, different subtypes and comorbidities (Banaschewski et al. 2010).

Our study included 2 genes related to the serotonergic system (HTR2A and TPH2). For both genes we found no association with AP problems. Quist et al. (2000) reported a preferential transmission of the ‘T’ allele of rs6314 in offspring with ADHD. However, other family-based association tests could not replicate these findings (Heiser et al. 2007; Guimaraes et al. 2007). In addition, the results of a meta-analysis of rs6314 and ADHD were not significant (Gizer et al. 2009). Regarding TPH2, studies have shown inconsistent results. Some studies have shown an association between multiple SPNs in TPH2 with ADHD (Gizer et al. 2009; Sheehan et al. 2005; Manor et al. 2008; Brookes et al. 2006), but others did not (Johansson et al. 2010; Sheehan et al. 2007). In addition, the direction of association for the specific alleles was not always consistent in those studies with a positive association. In conclusion, our data do not support a role of HTR2A and TPH2 genes in ADHD, but for HTR2A we may not have captured the complete genetic variability and we may have missed the genetic variant causing the susceptibility for AP.

The lack of positive findings could be due to including AP measures at age 3, which show a lower correlation with the AP measures at age 7, 10, and 12. In addition, the Overactive scale at age 3 only shares 2 items with AP at ages 7–12. So, it is questionable whether the two measures have the same content. However, in a large twin study (Rietveld et al. 2004) it was found that the overlap in additive genetic influences across ages 3–12 was between 42 and 68% and these percentages were more or less the same across all ages. In order to check this, we re-analyzed the data leaving out the AP scores at age 3 and obtained the same results.

As ADHD is more common in boys there is a discussion whether these sex differences could be explained by differences in genetic influences (Albayrak et al. 2008). For example, Biederman et al. (2008) reported a significant gender effect for the Val158Met allele of COMT, with an effect for males, but nor for females. However, a large twin study did not find evidence that different genes are involved in AP for boys and girls (Rietveld et al. 2003, 2004). In addition, we tested for sex-differences of the SNP effects, but these analyses did not reveal any sex differences in the SNP effects.

Our study has a number of limitations. The choice of the SNPs was limited by the availability of the genotype dataset. A shortcoming is that we could not apply the model to genes of the dopaminergic system. Until now, the most promising gene findings were obtained for the dopaminergic system. Another limitation is that our study is based on a population sample with only a few cases with ADHD, while gene finding may be more efficient by analyzing the extreme ends of the distribution (Eaves and Meyer 1994). This may have reduced the power. On the other hand, by using quantitative measures we have more information than by using dichotomized data.

A large advantage of the model is the gain in power by using an AP measure that is obtained over time and raters. In this way, we obtained a more reliable and persistent phenotype of AP. In future, this model could also be useful by analyzing the covariance of comorbid traits. In this case, the model is used to test effects of SNPs on factors common to the traits and on factors specific for a trait (Medland and Neale 2010). Furthermore, the model also offers an attractive option to model longitudinal data that may be characterized by many different patterns of missingness, and even possibly by the use of different instruments to assess the phenotype. As the test is carried out of at the latent factor level, these features of the data do not need to imply a disadvantage.

In sum, in the present study we found no evidence for an association between AP and SNPs of the HTR2A, COMT, TPH2 and BDNF genes. The only marginal effect was obtained for the rs6265 SNP of the BDNF gene. Despite the negative findings in this study, we believe that the design is useful in genetic association studies, especially in studies on developmental psychopathology (Middeldorp et al. 2010).

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research NWO/ZonMW (400-05-717, 911-03-016, 904-61-193, 985-10-002, 575-25-006, 920-03-268, 400-03-330, 451-04-034, 463-06-001, 904-57-94, 480-04-004), Neuroscience Campus Amsterdam (NCA); Center for Medical Systems Biology NIH R01 HL55976, NHBLI Mammalian Genotyping Service (Marshfield), NIDA grant DA-18673 (MCN), and European Research Council, Genetics of Mental Illness: (ERC-230374). Statistical analyses were carried out on the Genetic Cluster Computer (http://www.geneticcluster.org) which is financially supported by the Netherlands Scientific Organization (NWO 480-05-003). C.M. Middeldorp was supported by NWO (VENI grant 916-76-125).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

Edited by Elena Grigorenko and Brett Miller.

References

- Achenbach TM (1991) Manual for the child behavior checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont, Burlington

- Achenbach TM (1992) Manual for the child behavior checklist/2-3 and 1992 profile. Department Psychiatry, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT

- Albaugh MD, Harder VS, Althoff RR, Rettew DC, Ehli EA, Lengyel-Nelson T, et al. COMT Val158Met genotype as a risk factor for problem behaviors in youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:841–849. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albayrak O, Friedel S, Schimmelmann BG, Hinney A, Hebebrand J. Genetic aspects in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Neural Transm. 2008;115:305–315. doi: 10.1007/s00702-007-0839-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banaschewski T, Becker K, Scherag S, Franke B, Coghill D. Molecular genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an overview. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19:237–257. doi: 10.1007/s00787-010-0090-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels M, Van Beijsterveldt CEM, Derks EM, Stroet TM, Polderman TJ, Hudziak JJ, et al. Young Netherlands Twin Register (Y-NTR): a longitudinal multiple informant study of problem behavior. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2007;10:3–11. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen SE, Maher BS, Fanous AH, Kendler KS. Detection of susceptibility genes as modifiers due to subgroup differences in complex disease. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:960–964. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone SV. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2005;366:237–248. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66915-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Kim JW, Doyle AE, Mick E, Fagerness J, Smoller JW, et al. Sexually dimorphic effects of four genes (COMT, SLC6A2, MAOA, SLC6A4) in genetic associations of ADHD: a preliminary study. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:1511–1518. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma DI, de Geus EJ, Vink JM, Stubbe JH, Distel MA, Hottenga JJ, et al. Netherlands Twin Register: from twins to twin families. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006;9:849–857. doi: 10.1375/twin.9.6.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes K, Xu X, Chen W, Zhou K, Neale B, Lowe N, et al. The analysis of 51 genes in DSM-IV combined type attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: association signals in DRD4, DAT1 and 16 other genes. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:934–953. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Langley K, Milne B, Moffitt TE, O’Donovan M, Owen MJ, et al. A replicated molecular genetic basis for subtyping antisocial behavior in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:203–210. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheuk DK, Wong V. Meta-analysis of association between a catechol-O-methyltransferase gene polymorphism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Behav Genet. 2006;36:651–659. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner A, Kissling C, Hodges E, Hünnerkopf R, Clement RM, Dudley E, Freitag C, et al. Neurotrophic factor-related gene polymorphisms and adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) score in a high-risk male population. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:1476–1480. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bakker PI, Yelensky R, Pe’er I, Gabriel SB, Daly MJ, Altshuler D. Efficiency and power in genetic association studies. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1217–1223. doi: 10.1038/ng1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derks EM, Hudziak JJ, Dolan CV, Van Beijsterveldt TC, Verhulst FC, Boomsma DI. Genetic and environmental influences on the relation between attention problems and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Behav Genet. 2008;38:11–23. doi: 10.1007/s10519-007-9178-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derks EM, Hudziak JA, Boomsma DI. Genetics of ADHD, hyperactivity, and attention problems. In: Kim Y-K, editor. Handbook of behavior genetics. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 361–378. [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung C, Getchell M, Koposov R, Yrigollen C, Haeffel G, Klinteberg B, Oreland L, et al. Variation in the catechol-O-methyltransferase Val 158 Met polymorphism associated with conduct disorder and ADHD symptoms, among adolescent male delinquents. Psychiatr Genet. 2010;20:20–24. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e32833511e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves L, Meyer J. Locating human quantitative trait loci: guidelines for the selection of sibling pairs for genotyping. Behav Genet. 1994;24:443–455. doi: 10.1007/BF01076180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg J, Mei-Tal G, Steinberg A, Tartakovsky E, Zohar A, Gritsenko I, Nemanov L, et al. Haplotype relative risk study of catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): association of the high-enzyme activity Val allele with ADHD impulsive-hyperactive phenotype. Am J Med Genet. 1999;88:497–502. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19991015)88:5<497::AID-AJMG12>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Perlis RH, Doyle AE, Smoller JW, Goralnick JJ, Holmgren MA, et al. Molecular genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1313–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forero DA, Arboleda GH, Vasquez R, Arboleda H. Candidate genes involved in neural plasticity and the risk for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of 8 common variants. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2009;34:361–366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke B, Neale BM, Faraone SV. Genome-wide association studies in ADHD. Hum Genet. 2009;126:13–50. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0663-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genro JP, Kieling C, Rohde LA, Hutz MH. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and the dopaminergic hypotheses. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10:587–601. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gizer IR, Ficks C, Waldman ID. Candidate gene studies of ADHD: a meta-analytic review. Hum Genet. 2009;126:51–90. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0694-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes AP, Zeni C, Polanczyk GV, Genro JP, Roman T, Rohde LA, et al. Serotonin genes and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a Brazilian sample: preferential transmission of the HTR2A 452His allele to affected boys. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:69–73. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin JM, Newcorn JH, Schwartz ST, Sharma V, Siever LJ, Koda VH, et al. Age-related changes in the association between serotonergic function and aggression in boys with ADHD. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41:682–689. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00168-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiser P, Dempfle A, Friedel S, Konrad K, Hinney A, Kiefl H, et al. Family-based association study of serotonergic candidate genes and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a German sample. J Neural Transm. 2007;114:513–521. doi: 10.1007/s00702-006-0584-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hottenga JJ, Boomsma DI. QTL detection in multivariate data from sibling pairs. In: Neale BM, Ferreira MA, Medland SE, Posthuma D, editors. Statistical genetics: gene mapping through linkage and association. Taylor & Francis: Oxford; 2007. pp. 239–264. [Google Scholar]

- Hudziak JJ. The role of phenotypes (diagnoses) in genetic studies of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and related child psychopathology. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2001;10:279–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson S, Halmoy A, Mavroconstanti T, Jacobsen KK, Landaas ET, Reif A, et al. Common variants in the TPH1 and TPH2 regions are not associated with persistent ADHD in a combined sample of 1,636 adult cases and 1,923 controls from four European populations. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B:1008–1015. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG, Sörbom DI. PRELIS: a preprocessor for LISREL. Chicago: National Educational Resources; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kent L, Green E, Hawi Z, Kirley A, Dudbridge F, Lowe N, et al. Association of the paternally transmitted copy of common Valine allele of the Val66Met polymorphism of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene with susceptibility to ADHD. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:939–943. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koot HM, Van den Oord EJ, Verhulst FC, Boomsma DI. Behavioral and emotional problems in young preschoolers: cross-cultural testing of the validity of the Child Behavior Checklist/2–3. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1997;25:183–196. doi: 10.1023/A:1025791814893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman HM, Papolos DF, Saito T, Yu YM, Szumlanski CL, Weinshilboum RM. Human catechol-O-methyltransferase pharmacogenetics: description of a functional polymorphism and its potential application to neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmacogenetics. 1996;6:243–250. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199606000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanktree M, Squassina A, Krinsky M, Strauss J, Jain U, Macciardi F, Kennedy J, et al. Association study of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and LIN-7 homolog (LIN-7) genes with adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:945–951. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasky-Su J, Neale BM, Franke B, Anney RJ, Zhou K, Maller JB, et al. Genome-wide association scan of quantitative traits for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder identifies novel associations and confirms candidate gene associations. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:1345–1354. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Laurin N, Crosbie J, Ickowicz A, Pathare T, Malone M, Tannock R, et al. Association study of the brain-derived neurotropic factor (BDNF) gene in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:976–981. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnarsson S, Bjorklund A, Ernfors P. Learning deficit in BDNF mutant mice. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9:2581–2587. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macgregor S, Hottenga JJ, Lind PA, Suchiman HE, Willemsen G, Slagboom PE, et al. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms have negligible effect on human height. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2008;11:488–494. doi: 10.1375/twin.11.5.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manor I, Laiba E, Eisenberg J, Meidad S, Lerer E, Israel S, et al. Association between tryptophan hydroxylase 2, performance on a continuance performance test and response to methylphenidate in ADHD participants. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:1501–1508. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medland SE, Neale MC. An integrated phenomic approach to multivariate allelic association. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:233–239. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith GE, Callen S, Scheuer DA. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression is increased in the rat amygdala, piriform cortex and hypothalamus following repeated amphetamine administration. Brain Res. 2002;949:218–227. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(02)03160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middeldorp CM, Slof-Op ‘t Landt MCT, Medland SE, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Bartels M, Willemsen G, et al. Anxiety and depression in children and adults: influence of serotonergic and neurotrophic genes? Brain Genes Behav. 2010;9:808–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minica CC, Boomsma DI, van der Sluis S, Dolan CV (2010) Genetic association in multivariate phenotypic data: power in five models. Twin Res Hum Genet in press [DOI] [PubMed]

- Neale MC, Boker SM, Xie G, Maes HH (1999) Mx: statistical modeling, 5th edn. Department of Psychiatry, Richmond, VA 23298

- Neale BM, Lasky-Su J, Anney R, Franke B, Zhou K, Maller JB, et al. Genome-wide association scan of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:1337–1344. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyholt DR. A simple correction for multiple testing for single-nucleotide polymorphisms in linkage disequilibrium with each other. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:765–769. doi: 10.1086/383251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill MF, Heron-Maxwell CL, Shaw G. 5-HT2 receptor antagonism reduces hyperactivity induced by amphetamine, cocaine, and MK-801 but not D1 agonist C-APB. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;63:237–243. doi: 10.1016/S0091-3057(98)00240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quist JF, Barr CL, Schachar R, Roberts W, Malone M, Tannock R, et al. Evidence for the serotonin HTR2A receptor gene as a susceptibility factor in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Mol Psychiatry. 2000;5:537–541. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietveld MJ, Hudziak JJ, Bartels M, van Beijsterveldt CE, Boomsma DI. Heritability of attention problems in children: I. Cross-sectional results from a study of twins, age 3–12 years. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2003;117B:102–113. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.10024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietveld MJ, Hudziak JJ, Bartels M, van Beijsterveldt CE, Boomsma DI. Heritability of attention problems in children: longitudinal results from a study of twins, age 3 to 12. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:577–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Mora C, Ribases M, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Casas M, Bosch R, Boreatti-Hummer A, et al. Meta-analysis of brain-derived neurotrophic factor p.Val66Met in adult ADHD in four European populations. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B:512–523. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmelmann B, Friedel S, Dempfle A, Warnke A, Lesch K, Walitza S, Renner T, et al. No evidence for preferential transmission of common valine allele of the Val66Met polymorphism of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene (BDNF) in ADHD. J Neural Transm. 2007;114:523–526. doi: 10.1007/s00702-006-0616-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan K, Lowe N, Kirley A, Mullins C, Fitzgerald M, Gill M, et al. Tryptophan hydroxylase 2 (TPH2) gene variants associated with ADHD. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:944–949. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan K, Hawi Z, Gill M, Kent L. No association between TPH2 gene polymorphisms and ADHD in a UK sample. Neurosci Lett. 2007;412:105–107. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhausen HC. The heterogeneity of causes and courses of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;120:392–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PF, de Geus EJ, Willemsen G, James MR, Smit JH, Zandbelt T, et al. Genome-wide association for major depressive disorder: a possible role for the presynaptic protein piccolo. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:359–375. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapar A, Langley K, Fowler T, Rice F, Turic D, Whittinger N, et al. Catechol O-methyltransferase gene variant and birth weight predict early-onset antisocial behavior in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1275–1278. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai SJ. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder may be associated with decreased central brain-derived neurotrophic factor activity: clinical and therapeutic implications. Med Hypotheses. 2007;68:896–899. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst FC, van der Ende J, Koot HM. Handleiding voor de CBCL14–18. Rotterdam, Nederland: Afdeling Kinder- en Jeugdpsychiatrie/Eramus Universiteit; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Walther DJ, Peter JU, Bashammakh S, Hortnagl H, Voits M, Fink, et al. Synthesis of serotonin by a second tryptophan hydroxylase isoform. Science. 2003;299:76. doi: 10.1126/science.1078197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigginton JE, Cutler DJ, Abecasis GR. A note on exact tests of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:887–893. doi: 10.1086/429864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Mill J, Zhou K, Brookes K, Chen C, Asherson P. Family-based association study between brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene polymorphisms and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in UK and Taiwanese samples. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:83–86. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]