Abstract

The receptor tyrosine kinase MET is frequently amplified in human tumors, resulting in high cell surface densities and constitutive activation even in the absence of growth factor stimulation by its endogenous ligand, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF). We sought to identify mechanisms of signaling crosstalk that promote MET activation by searching for kinases that are coordinately dysregulated with wild-type MET in human tumors. Our bioinformatic analysis identified leucine-rich repeat kinase-2 (LRRK2), which is amplified and overexpressed in papillary renal and thyroid carcinomas. Down-regulation of LRRK2 in cultured tumor cells compromises MET activation and selectively reduces downstream MET signaling to mTOR and STAT3. Loss of these critical mitogenic pathways induces cell cycle arrest and cell death due to loss of ATP production, indicating that MET and LRRK2 cooperate to promote efficient tumor cell growth and survival in these cancers.

Keywords: kidney cancer, kinase bioinformatics, thyroid cancer

Constitutive and unregulated activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) is a common oncogenic mechanism in human cancers (1). Oncogenic activation of RTKs can be achieved by several different mechanisms that include somatic mutation, genetic amplification, autocrine growth factor stimulation, dysregulation of receptor trafficking pathways, or crosstalk with other kinase signaling cascades (2, 3). In many cases these separate mechanisms work in tandem to promote increased oncogenic signaling by an RTK. Prominent examples of these combinatorial mechanisms include coordinate amplification and somatic mutation of EGF receptor (EGFR) in lung cancer and coordinate overexpression of several different growth factor receptors and their cognate ligands in melanoma (4, 5).

The receptor tyrosine kinase MET, located at 7q31, is frequently amplified and highly activated in human tumors (6, 7). Although activating mutations to MET have been discovered, they are found in relatively few human tumor types (8–10). Tumors that contain genomic amplification of MET may also overexpress its ligand, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), thereby establishing an autocrine signaling loop to achieve constitutive MET activation (11–13). However, a number of tumor types demonstrate genomic amplification of MET without somatic mutation or coordinate overexpression of HGF, suggesting the existence of alternative mechanisms that activate MET in the absence of activating mutations or abundant ligand (6).

In this study we sought to identify oncogenic mechanisms that promote ligand-independent MET activation by searching for kinases that are coordinately dysregulated with MET in sporadic type 1 papillary renal cell carcinoma (RCC), which is a prototypical tumor type driven by amplification and overexpression of MET (14, 15). Unlike hereditary cases of papillary RCC in which MET activation is driven by specific point mutations, sporadic type 1 papillary tumors rarely demonstrate MET mutations (16, 17). Because HGF is also not significantly expressed in these tumors, we hypothesized that MET activation would be promoted by crosstalk with other dysregulated kinase signaling pathways.

Results and Discussion

LRRK2 Is Amplified and Overexpressed in Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma.

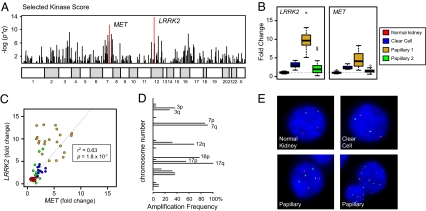

To identify candidate kinases that are coordinately dysregulated with MET, we used a two-component system that scores each kinase in the genome according to the significance of its overexpression (P value) and the frequency at which its genomic locus is amplified (q value). This approach, termed the selected kinase score (SKS), identified MET as the second most highly ranked kinase in type 1 papillary RCC (Fig. 1A and Table S1). MET was not highly ranked in other subtypes of RCC including the more common clear cell variant, suggesting that this approach can identify functionally relevant molecular alterations in specific cancer subtypes. Within type 1 papillary RCC cancer, only leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) was more highly ranked than the MET. Detailed analysis of LRRK2 mRNA expression demonstrates specific up-regulation of this kinase in type 1 papillary tumors compared with nondiseased kidney tissue, clear cell carcinomas, and type 2 papillary tumors (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1). More importantly, the mRNA expression level of LRRK2 positively correlates with that of MET in renal tumors (P = 1.8 × 10−7) (Fig. 1C). In the same samples, expression of HGF and other prominent oncogenes located near LRRK2 is unchanged compared with normal tissue (Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

LRRK2 and MET protein kinases are both overexpressed and amplified in papillary renal cell carcinoma. (A) Kinases that were both overexpressed and mapped to regions of frequent amplification in papillary type 1 renal cell carcinoma were identified using the select kinase score method. (B and C) Expression levels of MET and LRRK2 in nondiseased kidney (NK, n = 12), clear cell (CC, n = 10), papillary type 1 (P1, n = 22), and papillary type 2 (P2, n = 13) RCC. (D) Frequency of chromosome amplification in type 1 papillary RCC (n = 22) determined using the CGMA method. (E) FISH using probes directed to the LRRK2 (12q12, green) and MET (7q31, red) loci was performed on touch-prepped sections from the indicated tissues. Representative images of normal kidney (n = 2), clear cell RCC (n = 2), and papillary RCC (n = 5) are shown. See Table S2 for quantified results.

The 12q12 locus containing LRRK2 is subject to frequent alteration in human tumors, either as a focal or as a whole-chromosomal amplification (Fig. 1D) (18–20). To confirm that LRRK2 and MET are coordinately amplified in papillary RCC tumors, we performed dual-color FISH on renal tumors with probes targeted to LRRK2 (12q12) and MET (7q31) (Fig. 1E). Cells from normal kidney tissue and clear cell carcinomas demonstrated diploid copy number at both chromosomal loci. Conversely, the majority of cells in type 1 papillary tumors exhibited various levels of gain at 12q12 and 7q31. Aneuploid copy number for chromosome 12 ranged from three to seven copies, whereas copy number for chromosome 7 ranged from three to eight copies (Fig. 1E and Table S2). Importantly, tumor cells containing LRRK2 amplification almost invariably also contained amplification of MET.

LRRK2 Protein Is Overexpressed in Papillary RCC Tumor Cells.

Immunohistochemical detection of LRRK2 in normal kidney tissue demonstrates that this protein is enriched in the renal cortex compared with the medulla (Fig. 2A and Fig. S2 A and B). Higher magnification images of the renal cortex further show selective LRRK2 staining in the epithelium of proximal tubules, which can be distinguished from distal tubules by the presence of a luminal brush border (Fig. 2A, Inset). Notably, these cells also express the MET receptor, which is specifically restricted to the apical surface of proximal epithelia in the renal cortex (Fig. 2B, arrows).

Fig. 2.

Both LRRK2 and MET proteins are highly expressed in papillary renal cell carcinoma tissues. Immunohistochemistry with LRRK2 (A, C, and E) and MET (B, D, and F) antibodies was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (A and B) normal kidney tissue, (C and D) human papillary renal cell carcinoma, and (E and F) human clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Magnifications: 10× and (Insets) 20×. (Scale bars, 100 μm.) Arrows in A and B indicate proximal tubules in the renal cortex.

To evaluate coordinate expression of LRRK2 and MET proteins in human tumors, we performed immunostaining for LRRK2 and MET on serial sections from a panel of paraffin-embedded renal tumors (Fig. 2 C–F and Fig. S2 C–F). The results of these experiments confirm that LRRK2 and MET are coexpressed in the parenchyma of 55% (35/64) of all papillary tumors examined. In clear cell RCC, MET was highly expressed in 15% (10/66) of tumors, whereas LRRK2 was expressed at very low (10/66) or undetectable (56/66) levels in the same tissues (Fig. 2 E and F and Fig. S2 C–F). Importantly, there did not appear to be any correlation between MET and LRRK2 expression in clear cell tumors, consistent with the findings from our microarray data.

Both Caki-2 and SKRC39 cells are derived from human papillary RCC tumors (21, 22). To determine whether these cells are appropriate models for type 1 papillary RCC, we compared their expression of LRRK2 and MET to that of HK2 immortalized normal proximal tubule cells (23). Compared with HK2 cells, both Caki-2 and SKRC39 cells demonstrate higher levels of LRRK2 and MET at the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. S1 D and E). These data confirm that both cell lines are appropriate models of human papillary RCC that can be used to further dissect the role of LRRK2 in this cancer.

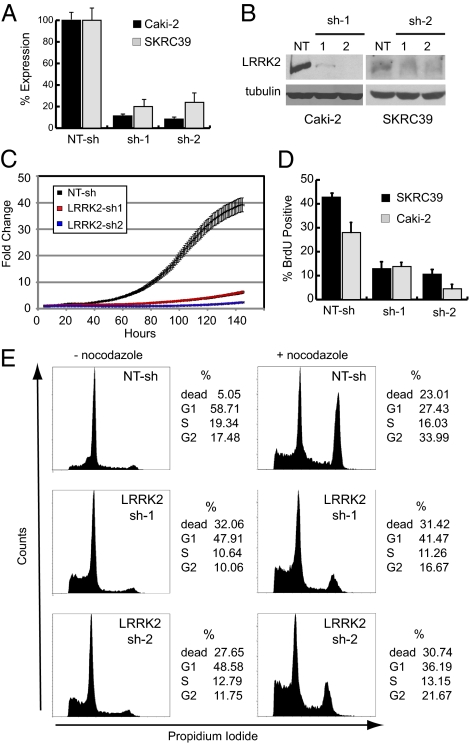

Depletion of LRRK2 Disrupts Tumor Cell Proliferation.

We used a loss-of-function strategy in cultured Caki-2 and SKRC39 cells, using lentiviral short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) to determine the functional role of LRRK2 in papillary renal tumors. We identified two different shRNAs to LRRK2 that effectively and stably decrease LRRK2 mRNA to ≈10% of basal mRNA levels (Fig. 3A). The shRNAs also decrease LRRK2 protein levels in these cells (Fig. 3B). Analysis of growth curves after stable depletion of LRRK2 demonstrates a decrease in cell growth over time compared with a control nontargeting shRNA (NT-sh) (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, stable silencing of LRRK2 in clear cell RCC tumor cell lines (786-O and 769-P) had no effect on their growth (Fig. S3 A–C), indicating that LRRK2 overexpression plays a specific role in papillary RCC as opposed to a general role in renal cancer cell growth.

Fig. 3.

Stable depletion of LRRK2 in papillary renal cell carcinoma lines leads to cell cycle arrest and cell death. Caki-2 and SKRC39 cells were stably infected with separate lentiviral shRNAs targeting LRRK2 (LRRK2 sh-1 and sh-2) or with a nontargeting control shRNA (NT-sh). (A) Quantitative RT-PCR for LRRK2 expression in Caki-2 and SKRC39 cells was performed to evaluate knockdown efficiency of the two LRRK2-targeted shRNAs. Data shown are the mean of triplicate measurements ± SD. (B) Immunoblots for LRRK2 expression in stable Caki-2 and SKRC39 cell lines. Immunoblotting for tubulin was used to demonstrate equal loading of protein lysates. (C) Ninety-six-hour growth curves for individual Caki-2 stable cell lines were generated; data are displayed as average fold change in cell number for four separate wells ± SD. (D) BrdU-labeled SKRC39 and Caki-2 stable cell lines were quantified by flow cytometry as a percentage of total cells analyzed from each line. Values shown are the mean of three separate cultures ± SD. (E) Propidium iodide-stained nuclei from Caki-2 stable cell lines treated with (+) or without (−) nocodazole were analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentage of cells in each phase of the cell cycle is indicated to the right of each histogram.

Incorporation of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) into papillary RCC cells is decreased upon knockdown of LRRK2, indicating that progression of tumor cells into S-phase is delayed when LRRK2 levels are decreased (Fig. 3D). To further define the cell cycle defect in LRRK2-deficient cells, we analyzed the cell cycle distribution of tumor cells by flow cytometry using propidium iodide staining to measure nuclear DNA content. Under basal growth conditions, both control (NT-sh) and LRRK2 knockdown cells are predominantly found in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (Fig. 3E). Cells lacking LRRK2, however, demonstrate a 40% reduction in S-phase content and a four- to fivefold increase in sub-G1 content compared with control cells, indicating an increase in cell death. To evaluate the ability of LRRK2-deficient cells to progress through the cell cycle, we used the microtubule depolymerizing agent nocodazole to arrest cells in G2 phase due to mitotic failure. Control (NT-sh) cells treated with nocodazole for 16 h show a significant shift of the cell population from G1 into G2; however, cells lacking LRRK2 demonstrate a defect in cell cycle progression by decreased progression out of G1 and into G2 (Fig. 3E). Together these data indicate that slowed growth of tumor cells after LRRK2 depletion results from a combination of G1 arrest and increased cell death.

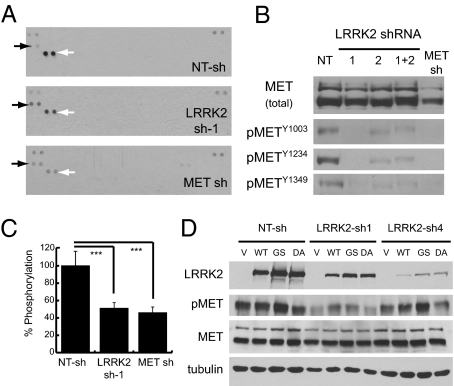

Depletion of LRRK2 Disrupts Activation of MET.

Because MET signaling was previously implicated in the mitogenic control of papillary RCC, we sought to determine whether MET and LRRK2 act in the same signaling pathway or in parallel pathways to regulate tumor cell growth. Under normal growth conditions, control (NT-sh) cells display strong activation of MET and comparatively weak activation of epidermal growth factor receptor, but little or no activation of other RTKs (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, depletion of LRRK2 leads to a significant decrease in MET phosphorylation similar to that of knocking down MET itself (Fig. 4A and Fig. S4 A and B). Both LRRK2 shRNAs independently decreased MET phosphorylation at three different residues involved in kinase activation (Y1234), signaling to downstream effectors (Y1349), and internalization from the cell surface (Y1003) (Fig. 4B). Notably, depletion of LRRK2 had almost no effect on total MET protein levels or localization to the cell surface, suggesting that the change in MET activation is not due to decreased expression or mislocalization (Fig. 4B and Fig. S4 C–E). Furthermore, LRRK2 does not appear to directly phosphorylate the cytoplasmic domain of MET as demonstrated by in vitro kinase assays using purified recombinant proteins (Fig. S4 G and H).

Fig. 4.

Stable depletion of LRRK2 disrupts basal and acute MET activation. (A) Protein lysates from the indicated stable SRKC39 cell lines were analyzed with Phospho-RTK antibody arrays. Solid arrows indicate duplicate EGFR antibody spots; open arrows indicate duplicate MET antibody spots. Duplicate positive control spots are located in the corners of each array for orientation. (B) Protein lysates were probed for total and phosphorylated MET protein by immunoblotting with phospho-tyrosine site-specific antibodies. (C) Protein lysates were analyzed for MET tyrosine phosphorylation using a sandwich ELISA. Values shown are the mean of quadruplicate measurements ± SD normalized to total MET protein for each sample. Significance of differences between samples was determined by unpaired Student's t test. ***P < 0.001. (D) SKRC39 stable knockdown cells were infected with HSV-1 expression vectors containing GFP only (V), wild-type (WT), hyperactive (GS, G2019S), or kinase-dead (DA, D1994A) LRRK2. After 72 h, cells were replated and harvested for immunoblot 24 h later. Protein lysates were probed for LRRK2 and total or phosphorylated MET protein.

We further quantified the decrease in basal MET phosphorylation using a sandwich ELISA and normalized the results to the amount of MET protein in each sample. The results of this assay demonstrate that LRRK2 and MET knockdown similarly decrease MET phosphorylation to ∼45% of control levels after normalization to total MET protein (Fig. 4C). Importantly, reintroduction of wild-type or hyperactive (G2019S) LRRK2 into LRRK2-depleted cells using a HSV-1 viral vector rescues MET activation, although use of a kinase-dead (D1994A) vector does not (Fig. 4D).

In addition to evaluating basal MET activation in vitro under continuous serum treatment, we also analyzed the effect of LRRK2 depletion on acute stimulation of MET by HGF. Cells were starved overnight (>16 h) in serum-free media to decrease basal MET activation and then stimulated with media containing recombinant human HGF. We found that depletion of LRRK2 from tumor cells has very little effect on their response to recombinant HGF, even when very low levels of ligand (2 ng/mL) are used (Fig. S4F). Interestingly, the kinetics and amplitude of HGF-induced MET phosphorylation differ significantly from those seen in basal serum stimulation, as HGF causes a more rapid, intense, and prolonged activation than that induced by serum. These data indicate that basal activation of MET in serum-cultured cells is distinct from acute, ligand-dependent activation and that LRRK2 is necessary for MET activation only in the absence of its ligand.

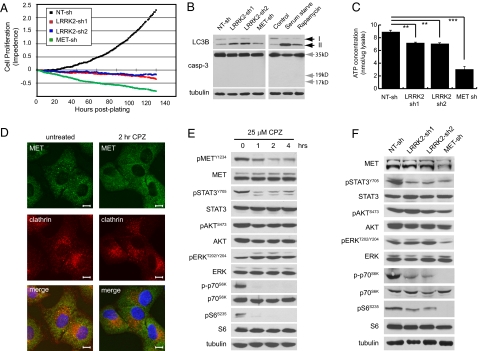

Depletion of LRRK2 and MET Produces an Energy Deficit and Induces Autophagy.

Long-term depletion of LRRK2 or MET from papillary RCC cells initially induces cell cycle arrest, which is followed by gradual cell death over the course of several days (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, cells lacking LRRK2 or MET fail to demonstrate biochemical evidence of caspase activation and do not display any of the typical morphological changes associated with apoptotic cell death (Fig. 5B). Rather, these cells appear swollen in shape and exhibit more pronounced features of autophagy including the accumulation of perinuclear and cytoplasmic vesicles that stain positive for the autophagic marker LC3B (Fig. S5 A and B) (24). Consistent with this observation, we found increased flux through the autophagic pathway in cells lacking LRRK2 or MET, demonstrated by increased autophagic processing of the proautophagic protein LC3B to its lower molecular weight isoform (Fig. 5B). Induction of autophagy in cells with reduced LRRK2 and MET likely results from a deficiency in energy production, indicated by the 15% and 60% decreases in ATP concentration observed in these cells, respectively (Fig. 5C). The more dramatic effect of MET knockdown can be attributed in part to the loss of glucose uptake, which is not seen in LRRK2-deficient cells (Fig. S5C).

Fig. 5.

Stable depletion of LRRK2 in papillary renal tumor cells selectively impairs endosomal MET signaling. (A) One hundred forty-hour growth curves for the indicated stable SKRC39 cell lines were generated. The cell index was normalized to zero after 24 h to allow for analysis of both proliferation and cell death. Values shown are quadruplicate measures of adherent cells at 1-h time points. (B) Protein lysates from SKRC39 stable cell lines were probed using the indicated antibodies. Control lysates were obtained from parental SKRC39 cells maintained under normal culture conditions (control), 24 h serum deprivation (serum starve), or 24 h of treatment with 100 nM rapamycin. Black arrows indicate the unprocessed (upper arrow) and processed (lower arrow) forms of LC3B. Gray arrows indicate the expected full-length and processed sizes of caspase-3. Immunoblots for tubulin demonstrate equal loading. (C) Normalized ATP concentrations were quantified in the indicated SKRC39 stable cell lines. Values shown are the mean of three separate biological replicates ± SD. Significance of differences between samples was determined by unpaired Student's t test. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (D) Confocal immunofluorescent images of Caki-2 cells treated with or without 25 μM chlorpromazine for 2 h and stained with antibodies to clathrin (red) and MET (green). Cells were costained with Hoechst 33258 to detect nuclei in each cell. Magnification: 60×. (Scale bars: 10 μm.) (E) SKRC39 cells were treated for the indicated times with 25 μM chlorpromazine. Protein lysates were probed for phosphorylated and total input of the indicated proteins. (F) Immunoblots of phosphorylated and total proteins were performed on replicate lysates of those in B.

Depletion of LRRK2 Selectively Compromises MET Signaling to Endosomal Effectors.

Previous studies have shown that activated MET signals to its downstream effectors from both the plasma membrane and endosomal compartments (25, 26). Notably, loss of endosomal trafficking has been shown to disrupt MET signaling to STAT3, but not ERK (26). Internalization of activated MET receptors can be blocked with the drug chlorpromazine (CPZ), which inhibits clathrin-mediated endocytosis and prevents localization of MET to the perinuclear endosomal compartment (Fig. 5D). In papillary RCC cells, inhibition of endosomal MET signaling with CPZ selectively down-regulates MET phosphorylation and signaling to STAT3 and the mTOR effectors p70S6K and S6, but has no effect on AKT or ERK activation (Fig. 5E). Importantly, knockdown of LRRK2 phenocopies the effects of CPZ at the level of cell signaling by selectively down-regulating STAT3 and mTOR (Fig. 5F). This phenotype is distinct from that of MET knockdown, which leads to decreased activation of all four of the mitogenic pathways we examined (Fig. 5F). This difference likely explains the more dramatic loss of cell viability and ATP production after knockdown of MET compared with that of LRRK2 and implies that LRRK2 functions downstream of MET activation at the level of endocytosis or endosomal vesicle trafficking (Fig. 5 A and C).

LRRK2 and MET Are Coordinately Upreglated in Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma.

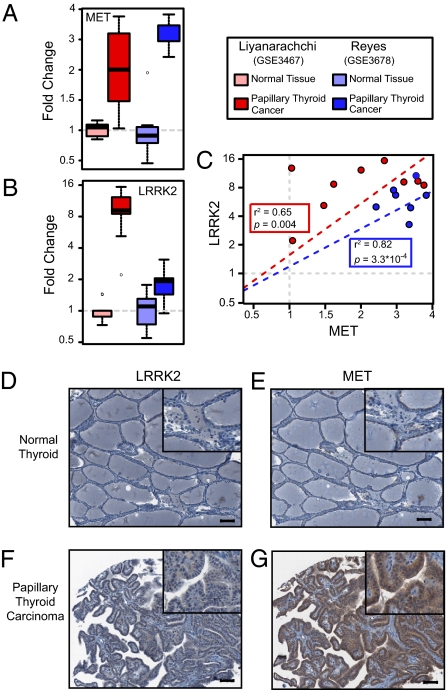

To determine whether LRRK2 and MET are coordinately overexpressed in other types of cancer, we examined previously published gene expression datasets to identify tumors that display amplification of chromosomes 7 and 12 and overexpress both LRRK2 and MET. We found that LRRK2 overexpression specifically correlates with elevated MET expression in papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) (Fig. 6 A–C). Furthermore, SKS analysis ranked LRRK2 as the number one and number three hits in two separate PTC datasets, suggesting that this kinase is similarly dysregulated in papillary renal and thyroid neoplasms (Fig. S6 A and B). Independent analyses from other previous publications have similarly identified MET and LRRK2 as being overexpressed in PTC (27, 28). Evidence for amplification of chromosomes 12 and 7 is also well documented in thyroid neoplasms, suggesting that the genetic mechanism we described for papillary RCC likely occurs in PTC as well (29–31).

Fig. 6.

LRRK2 and MET are coordinately overexpressed in papillary thyroid carcinoma. (A and B) Expression levels of MET and LRRK2 in nondiseased thyroid (n = 6 and 9) and PTC (n = 7 and 9) are shown. (C) Correlation between MET and LRRK2 in individual tissue samples was calculated for each study. (D–G) Immunohistochemistry for LRRK2 (D and F) and MET (E and G) was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues from nondiseased thyroid and PTC. Magnifications: 10× and (Insets) 20×. (Scale bars: 100 μm.)

To confirm our informatics findings, we performed immunohistochemistry for both MET and LRRK2 on a tissue microarray panel of human thyroid tumors. We found that MET is highly expressed in 68% (28/41) of PTC and that LRRK2 expression was significantly higher in PTC than in normal thyroid tissue in 39% (16/41) of tumors (Fig. 6 D–G). Importantly, tumors that expressed high levels of LRRK2 almost invariably expressed high levels of MET as well (94%, 15/16 tumors). These findings suggest that coordinate amplification of chromosomes 7 and 12 leads to the overexpression of MET and LRRK2 in multiple human malignancies and promotes the activation of specific signaling pathways required for cellular growth and survival in these cancers.

The role of large chromosomal abnormalities in the development and progression of cancer is poorly defined, although it occurs in many different cancer types (32). In this study we present evidence that coordinate gain of chromosomes 7 and 12 is associated with changes in expression of MET and LRRK2, respectively. Our data support a model in which these chromosomal aberrations function via a cooperative mechanism to promote MET signaling to specific downstream effectors. Whereas other factors located on chromosomes 7 and 12 could also support tumor development, our data minimally support a model in which the presence of both chromosomal abnormalities in papillary RCC and PTC is directly associated with activation of a specific oncogenic signal transduction pathway. Our data, however, do not exclude the possibility that LRRK2 could also facilitate signaling by other cell surface receptors in different cellular contexts, and further studies are required to investigate these potential interactions. It will also be important to determine the precise level of endocytosis or vesicular trafficking at which LRRK2 functions to better understand whether the mechanisms we have uncovered are more broadly applicable to other receptor signaling pathways.

The results of this study have three important implications of clinical significance. First, LRRK2 expression appears to be a relatively specific marker for the papillary subtypes of renal and thyroid carcinoma and may therefore be of clinical utility in diagnosing the histological and molecular identity of tumors derived from the kidney and thyroid (28). Second, this study also suggests that LRRK2 may be a valuable therapeutic target in tumor types driven by ligand-independent activation of MET, where monoclonal antibodies or peptide antagonists targeted to HGF will ostensibly have no effect on MET activation (33). Finally, the G2019S activating mutation to LRRK2 found in patients with Parkinson disease (PD) has been associated with increased cancer risk compared with control patients with sporadic PD, suggesting that specific polymorphisms in LRRK2 may predispose to both neurological disease and cancer (34). As such, our data suggest that targeting LRRK2 may be an attractive pharmacologic strategy to complement MET inhibitors in patients with specific papillary tumors or to treat patients with germ-line LRRK2 mutations that predispose them to both PD and epithelial cancers.

Materials and Methods

See SI Materials and Methods for expanded methods.

Gene Expression Profiling and Analysis.

Renal tumor gene expression profiles were generated previously by our group using the HG-U133 Plus 2.0 chipset (Affymetrix) from papillary renal cell carcinomas (n = 35), clear cell renal cell carcinomas (n = 10), and nondiseased kidney (n = 12). These data are deposited at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE7023 and GSE11024) (20). All expression analysis was performed using BioConductor version 2.0 software. Expression data were preprocessed using the RMA method implemented in the affy package with updated probe set mappings such that a single probe set describes each gene (35–37). Differentially expressed kinases were identified using a moderated t test implemented in the limma package (38). False discovery rates (gene q values) were calculated using the Benjamini and Hochberg method. Chromosomal abnormalities were identified from the gene expression data using the comparative genomic microarray analysis (CGMA) method implemented in the reb package (39). Chromosome P values <0.001 were considered to represent abnormal chromosomes (40). The final SKS for each kinase was obtained by multiplying the kinase gene q value by the median P value from the corresponding chromosome arm in the set of tumor samples.

FISH.

FISH BAC probes to human chromosomal loci 12q12 and 7q31 were labeled with SpectrumGreen and SpectrumOrange (Abbott Molecular). Probes were hybridized to frozen tumor touch preparations (clear cell, n = 2; papillary, n = 5) and matched normal tissue (n = 2) from the same patients using previously described methods (41).

Immunohistochemistry.

Freshly cut 5-μm tumor tissue sections were deparaffinized with xylenes and rehydrated through a series of graded ethanols. Subsequent staining steps were performed on a Discovery XT automated immunostainer (Ventana). Primary antibodies for MET (Met-4, 1:250) and LRRK2 (Prestige anti-LRRK2, 1:25) were used for immunostaining.

Cell Growth and Viability Assays.

Growth curves for stable cell lines were generated using the X-celligence system (Roche Applied Science). Measurements were recorded on an hourly basis for 72–144 h depending on the assay. All conditions were performed in quadruplicate, and values were normalized to the initial impedance after 8–12 h.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. George Vande Woude and Dr. Ted Dawson for providing the Met-4 and JH5514 (anti-LRRK2) antibodies, respectively. We also thank Rich West for help performing FACS analyses, Natalie Wolters for performing the ATP quantification assays, and Dr. Larry Louters (Calvin College, Grand Rapids, MI) for performing glucose uptake assays. HSV-1 helper free constructs were packaged by William J. Bowers (University of Rochester, Rochester, NY) and funded by the Michael J. Fox Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1012500108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Blume-Jensen P, Hunter T. Oncogenic kinase signalling. Nature. 2001;411:355–365. doi: 10.1038/35077225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haglund K, Rusten TE, Stenmark H. Aberrant receptor signaling and trafficking as mechanisms in oncogenesis. Crit Rev Oncog. 2007;13:39–74. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v13.i1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taniguchi CM, Emanuelli B, Kahn CR. Critical nodes in signalling pathways: Insights into insulin action. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:85–96. doi: 10.1038/nrm1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma SV, Bell DW, Settleman J, Haber DA. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:169–181. doi: 10.1038/nrc2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodeck U. Growth factor independence and growth regulatory pathways in human melanoma development. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1993;12:219–226. doi: 10.1007/BF00665954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birchmeier C, Birchmeier W, Gherardi E, Vande Woude GF. Met, metastasis, motility and more. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:915–925. doi: 10.1038/nrm1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corso S, Comoglio PM, Giordano S. Cancer therapy: Can the challenge be MET? Trends Mol Med. 2005;11:284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper CS, et al. Molecular cloning of a new transforming gene from a chemically transformed human cell line. Nature. 1984;311:29–33. doi: 10.1038/311029a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt L, et al. Germline and somatic mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of the MET proto-oncogene in papillary renal carcinomas. Nat Genet. 1997;16:68–73. doi: 10.1038/ng0597-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeffers M, et al. Activating mutations for the met tyrosine kinase receptor in human cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11445–11450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferracini R, et al. The Met/HGF receptor is over-expressed in human osteosarcomas and is activated by either a paracrine or an autocrine circuit. Oncogene. 1995;10:739–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koochekpour S, et al. Met and hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor expression in human gliomas. Cancer Res. 1997;57:5391–5398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turke AB, et al. Preexistence and clonal selection of MET amplification in EGFR mutant NSCLC. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glukhova L, et al. Mapping of the 7q31 subregion common to the small chromosome 7 derivatives from two sporadic papillary renal cell carcinomas: Increased copy number and overexpression of the MET proto-oncogene. Oncogene. 2000;19:754–761. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sweeney P, El-Naggar AK, Lin SH, Pisters LL. Biological significance of c-met over expression in papillary renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2002;168:51–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindor NM, et al. Papillary renal cell carcinoma: Analysis of germline mutations in the MET proto-oncogene in a clinic-based population. Genet Test. 2001;5:101–106. doi: 10.1089/109065701753145547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt L, et al. Novel mutations of the MET proto-oncogene in papillary renal carcinomas. Oncogene. 1999;18:2343–2350. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gunawan B, et al. Cytogenetic and morphologic typing of 58 papillary renal cell carcinomas: Evidence for a cytogenetic evolution of type 2 from type 1 tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6200–6205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reutzel D, et al. Genomic imbalances in 61 renal cancers from the proximal tubulus detected by comparative genomic hybridization. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2001;93:221–227. doi: 10.1159/000056987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang XJ, et al. A molecular classification of papillary renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5628–5637. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pulkkanen KJ, et al. Characterization of a new animal model for human renal cell carcinoma. In Vivo. 2000;14:393–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang XJ, et al. Classification of renal neoplasms based on molecular signatures. J Urol. 2006;175:2302–2306. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00255-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryan MJ, et al. HK-2: An immortalized proximal tubule epithelial cell line from normal adult human kidney. Kidney Int. 1994;45:48–57. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroemer G, Levine B. Autophagic cell death: The story of a misnomer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:1004–1010. doi: 10.1038/nrm2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammond DE, et al. Endosomal dynamics of Met determine signaling output. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:1346–1354. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-09-0578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kermorgant S, Parker PJ. Receptor trafficking controls weak signal delivery: A strategy used by c-Met for STAT3 nuclear accumulation. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:855–863. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giordano TJ, et al. Molecular classification of papillary thyroid carcinoma: Distinct BRAF, RAS, and RET/PTC mutation-specific gene expression profiles discovered by DNA microarray analysis. Oncogene. 2005;24:6646–6656. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prasad NB, et al. Identification of genes differentially expressed in benign versus malignant thyroid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3327–3337. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roque L, Serpa A, Clode A, Castedo S, Soares J. Significance of trisomy 7 and 12 in thyroid lesions with follicular differentiation: A cytogenetic and in situ hybridization study. Lab Invest. 1999;79:369–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Criado B, et al. Detection of numerical alterations for chromosomes 7 and 12 in benign thyroid lesions by in situ hybridization. Histological implications. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:136–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodrigues R, et al. Comparative genomic hybridization, BRAF, RAS, RET, and oligo-array analysis in aneuploid papillary thyroid carcinomas. Oncol Rep. 2007;18:917–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duesberg P, et al. How aneuploidy may cause cancer and genetic instability. Anticancer Res. 1999;19(6A):4887–4906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karamouzis MV, Konstantinopoulos PA, Papavassiliou AG. Targeting MET as a strategy to overcome crosstalk-related resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:709–717. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saunders-Pullman R, et al. LRRK2 G2019S mutations are associated with an increased cancer risk in Parkinson disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25:2536–2541. doi: 10.1002/mds.23314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dai M, et al. Evolving gene/transcript definitions significantly alter the interpretation of GeneChip data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e175. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gentleman RC, et al. Bioconductor: Open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Irizarry RA, et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3(1) doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. Article3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Furge KA, Dykema KJ, Ho C, Chen X. Comparison of array-based comparative genomic hybridization with gene expression-based regional 2expression biases to identify genetic abnormalities in hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:67. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Furge KA, et al. Detection of DNA copy number changes and oncogenic signaling abnormalities from gene expression data reveals MYC activation in high-grade papillary renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3171–3176. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsuda D, et al. French Kidney Cancer Study Group Identification of copy number alterations and its association with pathological features in clear cell and papillary RCC. Cancer Lett. 2008;272:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.