Abstract

Cytoplasmic Ca2+ is known to regulate Na+–Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) activity by binding to two adjacent Ca2+-binding domains (CBD1 and CBD2) located in the large intracellular loop between transmembrane segments 5 and 6. We investigated Ca2+-dependent movements as changes in FRET between exchanger proteins tagged with CFP or YFP at position 266 within the large cytoplasmic loop. Data indicate that the exchanger assembles as a dimer in the plasma membrane. Addition of Ca2+ decreases the distance between the cytoplasmic loops of NCX pairs. The Ca2+-dependent movements detected between paired NCXs were abolished by mutating the Ca2+ coordination sites in CBD1 (D421A, E451A, and D500V), whereas disruption of the primary Ca2+ coordination site in CBD2 (E516L) had no effect. Thus, the Ca2+-induced conformational changes of NCX dimers arise from the movement of CBD1. FRET studies of CBD1, CBD2, and CBD1–CBD2 peptides displayed Ca2+-dependent movements with different apparent affinities. CBD1–CBD2 showed a Ca2+-dependent phenotype mirroring full-length NCX but distinct from both CBD1 and CBD2.

The Na+–Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) is a plasma membrane protein that uses the electrochemical gradient of Na+ to extrude Ca2+ from cells. NCX is organized into nine transmembrane segments (TMSs) with a large cytoplasmic loop between TMSs 5 and 6 composed of two adjacent Ca2+-binding domains, CBD1 and CBD2, flanked by linkers that connect the CBDs to the TMSs (1).

Regulatory Ca2+ binds to the CBDs, stimulates exchanger activity, but is not transported. It also alleviates Na+-dependent inactivation (2, 3). CBD1 and CBD2 bind four and two Ca2+ ions, respectively. Recent studies have identified the important role of Ca2+ sites 3 and 4 of CBD1 and site 1 of CBD2 in regulating Ca2+ transport (4–6). How the binding of Ca2+ to these sites is translated into exchanger activation is unknown.

CBD1 and CBD2 share a similar structure consisting of seven antiparallel β-strands arranged as a β-sandwich (4, 6–12) with the Ca2+-binding sites at one end. The CBDs are only separated by 5–7 aa and therefore are organized in a head-to-tail fashion (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

NCX undergoes Ca2+-dependent conformational changes. (A) Secondary structure of the fluorescent-tagged exchanger illustrating the relative position of the two Ca2+–binding domains (CBD1 and CBD2) and fluorophores (FP). Small spheres indicate bound Ca2+. (B) Effect of changes in intracellular Ca2+ on CFP (□) and YFP (■) emissions (Left) and corresponding FRETR (Right) after coexpression of NCXC and NCXY. (C) Changes in normalized FRETR versus free [Ca2+] for NCXC + NCXY. FRETR values were normalized to their maximum and fitted to a single Hill function (Kh = 40 nM and Hill coefficient =1.8).

To advance our understanding on the molecular mechanism leading to NCX activation by cytoplasmic Ca2+, we inserted either YFP or CFP at position 266 within the large cytoplasmic loop of NCX. Additionally, we expressed fusion proteins composed of CBD1, CBD2, or CBD1 plus CBD2 (CBD12) flanked by CFP and YFP to detect Ca2+-induced movements in real time by FRET. FRET efficiency (FRETE) depends strongly on the distance between two fluorophores, and the technique can be used for monitoring protein–protein interactions and conformational changes (13).

Our results indicate that FRET occurs between adjacent exchangers, revealing that NCX exists as a dimer in the plasma membrane. Previous studies have demonstrated the multimeric nature of NCX (14, 15) without, however, resolving its subunit composition. We also show that regulatory Ca2+ decreases the distance between the paired NCXs by triggering conformational changes within the cytoplasmic portion of the protein linking CBD1 to TMS 5. Our results show the detection of regulatory Ca2+-dependent movements in the full-length functional exchanger.

Results

Ca2+-Dependent Conformational Changes Between NCX Monomers.

To investigate the Ca2+-dependent movements of NCX during Ca2+ regulation, YFP or CFP proteins were inserted at amino acid 266 of NCX to give NCXC or NCXY (Fig. 1A). Introduction of fluorophores at amino acid 266 does not alter the biophysical properties of NCX, including regulation by cytoplasmic Na+ or Ca2+, as shown previously (16). Because NCX can form oligomers (14, 15), we hypothesized that FRET would occur between adjacent exchangers.

To have fast access to the cytoplasmic face of NCX, we used fluorescent plasma membrane sheets (FluoPMS) derived from Xenopus laevis oocytes (17) (SI Materials and Methods). FluoPMS were prepared from oocytes coexpressing NCXC and NCXY to monitor Ca2+-dependent movement as changes in the YFP/CFP ratio (FRETR). As shown in Fig. 1B, addition of 13 μM Ca2+ to the bath triggered an increase in FRETR, which was reversed by 10 mM EGTA. Thus, regulatory Ca2+ promotes movements in the cytoplasmic domains of NCX, decreasing the distance between the large intracellular loops of adjacent exchangers. To determine the range of Ca2+ needed to trigger movements in the full-length exchanger, FRETR was measured at different free Ca2+ concentrations. These values were fitted to a Hill function. A 50% change in FRETR was induced by ∼40 nM Ca2+ (Fig. 1C).

NCX Exists as Dimer.

The detection of FRET between NCX molecules suggests that NCX exists in a multimeric complex. Alternatively, FRET may arise from a nonspecific encounter of the two fluorophores because of a high density of NCX molecules within the membrane. Based on theoretical models (13, 18, 19), two conditions need to be satisfied to determine true oligomerization: (i) the level of energy transfer (FRETE) between units within a true oligomer is expected to rise with increasing concentration of acceptor protein (donor protein concentration is constant) until a plateau is reached, which is when donors are all coupled to acceptors; and (ii) the FRETE should be independent of the absolute protein concentration. Fig. 2A shows the effects of increasing the level of NCXY acceptors while keeping the NCXC donors constant. An increase in FRETE [calculated by using the gradual acceptor photobleaching protocol (20)] is observed until a plateau is reached (FRETE = 0.2). This hyperbolic curve satisfies the first condition for true oligomerization (18, 19), in contrast to the almost linear relationship between FRETE and acceptor concentration expected for random encounters. Although FRET generated by protein overexpression (Erandom) is also predicted to plateau when the cell surface is packed with proteins, this occurs at extremely high protein concentrations, not attainable for overexpressed NCX. We estimate that at least 200,000 exchangers per μm2 (18, 21) are required to saturate Erandom. However, the maximal density of NCX in Xenopus laevis oocytes is 300–400 exchangers per μm2 (22), generating a FRETE of about 0.01 by random associations, well below our measurement of 0.1.

Fig. 2.

NCX exists as dimer in the plasma membrane. (A) Dependence of FRETE on NCXY expression (measured as fluorescence emission intensity, a.u.) at a constant NCXC expression level and in presence of 13 μM Ca2+. Points were fitted to FRETE = (FRETmax * FYFP)/FYFP + K, where FRETmax is the maximal FRETE, FYFP is YFP emission intensity, and K is analogous to a dissociation constant (19). F test comparison between hyperbolic and linear regressions indicates that a nonlinear model best fits the points (P < 0.0001). (B) FRETE versus protein concentration measured as the sum of YFP (before bleaching) and CFP (after YFP bleaching) fluorescence intensity. FRETE was measured in the absence of Ca2+ from FluoPMS expressing a constant ratio of NCXY to NCXC of 0.50 ± 0.03 (n = 20) or 4.3 ± 0.2 (n = 18) in absence of Ca2+ and 4.3 ± 0.1 (n = 28) in presence of 13 μM Ca2+. The R2 values are 0.086, 0.00002, and 0.01, respectively. (C) Plot of FRETE as function of the NCXY/NCXC concentration ratio in absence or presence of 13 μM Ca2+. Points were fitted to a hyperbole as described in the Materials and Methods and in ref. 23. Each point is the average of 4–12 measurements. (D) Comparison between the experimental data shown in Fig. 2C (normalized to their maxima) and modeled FRETE curves for dimer, trimer, and tetramer according to [(a + d)n − an − dn]/[(a + d)n − an − dn + ndn] (24), where n is the number of molecule(s) in the oligomers, a is the number of acceptors, and d is the number of donors. The SDs of the vertical distances of the points from the lines describing the dimer, trimer, or tetramer models are 0.08, 0.18, and 0.24 (0 Ca2+) and 0.08, 0.17, and 0.24 (13 μM Ca2+).

To verify the second condition, we investigated the relationship between FRETE and protein expression levels. Because FRETE depends on the fraction of donor–acceptor complexes with respect to total donor molecules, we measured FRETE from patches expressing a constant ratio of acceptors, NCXY to donors, NCXC, but with different total expression levels. As shown in Fig. 2B, our data indicate that FRETE remained constant despite different total NCX expression levels both in the absence or presence of Ca2+. The combined data are consistent with NCX existing as a functional oligomer in the plasma membrane.

To determine the maximal FRETE between tagged exchangers, we measured FRETE from FluoPMS expressing different ratios of NCXY and NCXC in the presence and absence of Ca2+ and generated FRET saturation curves as shown in Fig. 2C. The measured FRETE increases with the probability of interaction of CFP with YFP and therefore with the relative amounts of free acceptors and donors. The FRET titration curves could be fitted to a hyperbolic function (23). Ca2+ significantly increased the extrapolated maximal FRETE value, indicating movements between the large cytoplasmic loops of neighboring NCX proteins.

Since FRETE versus NCXY/NCXC depends on the stoichiometry of the oligomer, we compared our experimental values to mathematical models describing the expected FRETE saturation curves for dimers, trimers, and tetramers (24). Fig. 2D shows that the theoretical dimer curve best approximates the experimental data, suggesting that oligomerized NCX exists predominately as a dimer in the membrane.

CBD1 Confers Ca2+-Dependent Movement to the Full-Length NCX.

To determine the contributions of the individual CBDs to the Ca2+-induced movements of NCX, we mutated residues in NCX that disrupt Ca2+ binding to either CBD1 or CBD2. Two separate constructs were engineered. The first consisted of NCXC and NCXY exchangers with three mutations in CBD1: D421A, E451A, and D500V (NCXC-CBD1 and NCXY-CBD1), which disrupt all four Ca2+-binding sites of CBD1 (6, 8, 10), and the second construct had the mutation E516L (site 1 in CBD2, NCXC-CBD2, and NCXY-CBD2) (4, 5). Mutations in CBD1 drastically decreased the sensitivity of NCX peak current for regulatory Ca2+ whereas mutant E516L in CBD2 abolished Ca2+ regulation of NCX (Fig. S1). Analogous results have previously been reported in the untagged NCX with the same mutation(s) (4), emphasizing the fact that the tagged NCX behaves in a manner similar to that of untagged NCX.

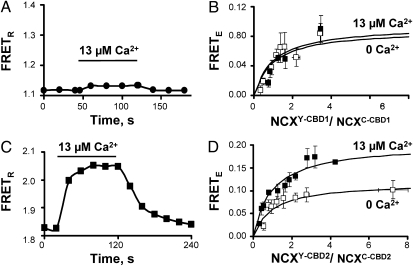

We next investigated the Ca2+-dependent conformational changes of these mutants. As shown in Fig. 3A, the CBD1 mutant abolished Ca2+-dependent movements of NCX, although changes in FRETR of ∼0.02, at the limit of our detection capability, were observed upon addition of ∼40 μM Ca2+. FRETE was also unaffected by Ca2+ (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the CBD2 mutant did not significantly modify either the FRETR (Fig. 3C) or FRETE (Fig. 3D) response to Ca2+. These results indicate that the Ca2+-dependent conformational changes of NCX are associated with the occupancy of Ca2+-binding sites within CBD1. The conformational changes associated with CBD1, however, are not sufficient to regulate NCX if CBD2 is nonfunctional.

Fig. 3.

Mutations within CBD1 abolish Ca2+-dependent conformational changes. (A and B) Effect of intracellular Ca2+ on changes in FRETR and FRETE between CFP- and YFP-tagged exchangers carrying the mutations D421A, E451A, and D500V (NCXC–CBD1 + NCXY-CBD1). Mutations within CBD1 abolished Ca2+-dependent FRET changes. (C and D) FRETR and FRETE measurements from fluorescent-tagged exchangers with E516L in CBD2 (NCXC–CBD2 + NCXY-CBD2). Note the increases in FRETR and FRETE upon addition of cytoplasmic Ca2+.

Ca2+-Dependent Conformational Changes in Isolated CBD1, CBD2, and CBD12.

To further explore the effects of the binding of Ca2+ to the cardiac CBDs (NCX1.1 isoform), we studied their Ca2+-dependent properties as single Ca2+-binding domains. Based on crystal structures (4, 6–12). CBD1 encompasses residues 371–501, CBD2 encompasses residues 501–689, and CBD12 encompasses residues 371–689. We linked these constructs to CFP and YFP at their N and C termini (CCBD1Y, CCBD2Y, and CCBD12Y), respectively, and investigated their responses to Ca2+. All constructs were targeted to Xenopus laevis oocyte plasma membranes by fusing the Ki-Ras sequence to the C termini of YFP (25). The Ca2+-dependent movements were first monitored as changes in FRETR. Examples of changes in the FRETR are shown in Fig. 4 A–C. Rapid switches between solutions with different Ca2+ concentrations caused a decrease in FRETR, indicating that the distance between the fluorophores increases upon binding of Ca2+ to all three peptides.

Fig. 4.

Cytoplasmic Ca2+ triggers movement in the isolated Ca2+-binding domains. (A–C) Effect of Ca2+ on FRETR signals generated by CCBD1Y (A), CCBD2Y (B), and CCBD12Y (C) in FluoPMS. Note the lower Ca2+ concentrations required to activate movements in CBD12. Images were acquired every 10 s. (D) Changes in normalized FRETR value versus free [Ca2+]. Points, which are averaged between four and six experiments, were fitted to a Hill function. Kh values are 0.20 μM, 12 μM, and 0.010 μM for CBD1, CBD2, and CBD12. Average Kh values obtained from the single experiments are (in μM) 0.19 ± 0.01 (n = 4), 12 ± 0.01 (n = 6), and 0.014 ± 0.01 (n = 4), respectively. For CBD12, only the high Ca2+ affinity component was analyzed because the movements associated with higher Ca2+ concentrations were too small for accurate analysis. (E) Average FRETE values in the absence and presence of 13 μM Ca2+ for CBD1 and CBD12 and 139 μM Ca2+ for CBD2. Values are 0.35 ± 0.01 and 0.23 ± 0.01 for CBD1, 0.184 ± 0.003 and 0.162 ± 0.003 for CBD2, and 0.114 ± 0.003 and 0.090 ± 0.004 for CBD12, respectively. CCBD1Y-L is a lengthened construct consisting of residues 371–508, and CCBD12Y-CBD1 is CCBD12Y with mutations D421A, E451A, and D500V in CBD1. Values are 0.28 ± 0.01 and 0.23 ± 0.01 for CCBD1Y-L and 0.14 ± 0.01 and 0.13 ± 0.01 for CCBD12Y-CBD1. Number of experiments is indicated within each bar.

As shown in Fig. 4D, the Kh values for Ca2+ of CCBD1Y and CCBD2Y are 0.20 and 12 μM, respectively. The response of CCBD12Y to Ca2+ appears biphasic with apparent Ca2+ affinities of ∼0.01 and 16 μM with relative contributions of ∼80% and 20%, respectively. We lack confidence in the quantification of the low-affinity component of CCBD12Y because of the small changes in FRETR. The finding that CBD12 has a higher affinity for Ca2+ than either CBD1 or CBD2 contrasts with an earlier study (26) but is consistent with the result that CBD12 has substantially altered Ca2+ dissociation kinetics (see below). Our data indicate that CCBD12Y behaves differently than the sum of the separate CCBD1Y and CCBD2Y moieties, indicating an interaction between the two domains.

Consistent with the ratiometric data, FRETE values decreased after Ca2+ application (Fig. 4E), showing the most prominent decrease in CBD1. As observed for NCX, mutation of residues 421, 451, and 500 abolished the Ca2+-dependent movements of CCBD12Y (CCBD12Y-CBD1 in Fig. 4E): FRETE values are 0.14 ± 0.01 and 0.13 ± 0.01 in the absence and presence of 13 μM Ca2+, stressing the role of CBD1 in triggering these movements.

We then resolved the temporal changes of FRETR upon addition or removal of Ca2+ to estimate the speed of the Ca2+-dependent movements. Examples of FRETR changes upon binding of Ca2+ are shown in Fig. S2. Generally, we find that higher concentrations of Ca2+ result in faster changes in FRETR. The changes in FRET follow a monoexponential time course. CCBD1Y had slow kinetics at 140 nM free Ca2+ (τ = 0.38 ± 0.03 s, n = 6), which accelerated to the limit of our temporal resolution (∼150 ms) in response to micromolar Ca2+ concentrations. Fast kinetics have been previously described (26, 27), which would not be resolved because of our image sampling rate. Similarly, CCBD2Y and CCBD12Y showed slow movements upon addition of low levels of Ca2+ and faster movements when Ca2+ was raised to higher levels (Fig. S2).

Removal of Ca2+ triggered different responses among the CBDs (Fig. 5). In the case of CCBD1Y and CCBD2Y, FRETR changed too rapidly for an accurate measurement (<0.15 s), whereas CBD12 showed a substantially slower time course (τ = 16 ± 2 s, n = 8). Similar kinetics were measured for NCX dimers (τ = 19 ± 4 s, n = 7), suggesting that the movements observed in NCX originate from the two CBDs acting in concert.

Fig. 5.

Removal of Ca2+ causes a slow conformational change in CBD12 and in the full-length NCX. (A–C) FRETR changes upon removal of regulatory Ca2+ for the indicated constructs. Images were acquired every 200 or 500 ms. (D) Summary of time constants for FRETR changes upon removal of Ca2+ for CBD12 and NCX. #Values for the individual CBDs represent an upper limit and cannot be accurately measured because of our limited frame rate (5 Hz). Faster kinetics are likely to occur as previously reported (26, 27).

To rule out a possible contribution of intermolecular FRET due to oligomerization of the CBDs, we fused either CFP or YFP to the N or C terminus of CBD12 to generate YCBD12, CCBD12, and CBD12C. HEK cells were then transfected with the cytosolic YCBD12 in the presence of either CCBD12 or CBD12C. None of the combinations were able to generate FRET (a FRETE of 0.01 was calculated in both cases), indicating that free CBDs did not oligomerize and that FRET only occurs intramolecularly. Finally, FRETE measured from the CBDs targeted to the plasma membrane was independent of the expressed protein concentration, indicating that FRET was not caused by crowding of CBDs in the membrane (Fig. S3).

Discussion

The Na+-Ca2+ exchanger is regulated by cytoplasmic Ca2+, which antagonizes Na+-dependent inactivation and directly activates NCX (2, 3). This Ca2+ binds to two domains, CBD1 and CBD2, the structures of which have been determined (4, 6–12). The mechanisms involved in Ca2+ regulation are not well understood. To gain insight into these molecular processes, we used FRET measurements to characterize the Ca2+-dependent conformational changes both in the full-length exchanger and in isolated CBD peptides.

First, we assessed FRET between full-length NCXs, each labeled with a single fluorophore. Our data indicate that adjacent exchangers are close enough to generate FRET, confirming previous crosslinking studies that NCX exists as oligomers (15). By analyzing the changes in FRET as a function of fluorophore concentration, we determined that the exchanger likely exists as a dimer in the plasma membrane, similarly to the NCKX transporter (28). In some cases, oligomerization of transporters regulates either function (29–31) or trafficking (32). We have previously shown that coexpression of a tagged WT NCX with a nonfunctional mutant caused retention of the tagged NCX within the endoplasmic reticulum (14). Thus, dimerization may be important for trafficking NCX to the plasma membrane. Whether interactions between neighboring NCX subunits influence transport function remains to be determined.

Next, we determined whether cytoplasmic Ca2+ influences the spatial arrangement of the dimer. Upon addition of Ca2+, the pair NCXC + NCXY shows an increase in FRET, indicating that the binding of Ca2+ decreases the distance between the N-terminal portions of the adjacent large cytoplasmic loops. These results provide a physical measurement of Ca2+-dependent movements within NCX.

We demonstrated by mutagenesis that the dimer movements arise mainly from the binding of Ca2+ to CBD1. Mutations that eliminate Ca2+ binding to CBD1 severely decrease the apparent affinity for Ca2+ to regulate NCX activity (5) and abolish the Ca2+-dependent changes in FRETE, ruling out the Ca2+ transport site as the source of FRET changes. The residual low-affinity Ca2+ regulation is attributable solely to CBD2 (5). In contrast, a mutation within CBD2 that abolishes Ca2+ regulation, left Ca2+-dependent changes in FRET fully intact. Possibly, fluorophores at position 266 fail to track changes in conformation induced by Ca2+ binding to CBD2.

Overall, these results are consistent with previous findings that Ca2+ binding to CBD1 both induces a substantial conformational change (8, 33–35) and controls the affinity of Ca2+ regulation (5, 34, 36). Nevertheless, the conformational changes evoked by CBD1 are not sufficient to account for all of the steps involved in Ca2+ regulation because a functional CBD2 is also required.

An important step for understanding the physiological role of Ca2+ regulation of NCX is to determine its affinity for Ca2+, a nontrivial task because apparent affinities are typically measured under different conditions by using diverse techniques. For example, electrophysiological measurements of exchanger activity are generally carried out in the presence of high intracellular Na+ with varying Ca2+ concentrations. Increasing cytoplasmic Ca2+ activates NCX but also competes with Na+ at the transport site, thereby decreasing exchanger activity (2, 3). As a result, estimates of NCX affinity for regulatory Ca2+ have ranged from 22 nM in whole-cell measurements (37) to 800 nM in giant excised patches (5). In this work, we find that the concentration of Ca2+ needed to increase FRETR by 50% between two exchangers is ∼40 nM, which suggests that, at resting levels of myocardial Ca2+ (∼100 nM), NCX has already undergone large changes in conformation, limiting the effects of further increases of Ca2+ during excitation–contraction coupling. However, two issues must be considered: First, our experiments were conducted in the absence of both Na+ (to prevent Na+-dependent inactivation) and Mg2+. Although cytoplasmic Na+ does not alter the Ca2+ binding properties of the isolated CBDs (27), its effects on the Ca2+ regulation of the full-length exchanger have not been investigated. Intracellular Mg2+ decreases both the affinities of NCX and the isolated CBDs for Ca2+ (27, 33, 38). Thus, Ca2+-dependent conformational changes of NCX associated with CBD1 may indeed take place in a cardiac cell. Second, the lower affinities measured for regulation may involve binding of Ca2+ to CBD2, after CBD1 is saturated. As we have shown, CBD2 is essential for regulation, making this possibility feasible. Binding of Ca2+ to CBD2 produces only minor FRET changes that are not readily detectable in NCX experiments. We are currently investigating these issues.

To understand how the individual Ca2+-binding domains behave during regulation of NCX, we investigated the movements of membrane-targeted CBDs. We first analyzed the response of CBD1 to Ca2+. We had previously investigated the properties of the soluble CBD1 flanked by CFP and YFP encompassing residues 371–508 and shown that binding of Ca2+ to this domain decreases FRET (33). However, after consideration of the crystal structure (10), we removed residues 502–508 from CBD1 because they form part of the first β-strand of CBD2. Truncation of residues 502–508 did not affect the Ca2+ affinity of CBD1, although the change in the FRETE signal was somewhat larger (Fig. 4E with the longer form of CBD1 designated as CCBD1Y-L). The result has two important implications: residues 502–508 are not essential for the Ca2+-dependent movements in CBD1 and targeting the construct to the plasma membrane did not affect Ca2+ binding properties.

CBD2 behaved similarly to CBD1: Ca2+ binding resulted in an increase in the distance between the fluorophores, although the movements were smaller and less sensitive to Ca2+ when compared with CBD1 (Kh = 12 μM vs. Kh = 200 nM for CBD1). The results are consistent with previous reports showing smaller structural effects of Ca2+ on CBD2 than CBD1 and a reported lower affinity of CBD2 for Ca2+ (4, 7, 26, 27). The greater FRETE changes observed for CBD1 might be accounted for by stabilizing or rigidifying effects of Ca2+ binding, as determined by other structural approaches (8–11).

The Ca2+-binding domains of NCX are adjacent to each other and are aligned in a head-to-tail arrangement (Fig. 1) with the residues coordinating Ca2+ ions in CBD1 in proximity to the end of CBD2 that does not bind Ca2+. The arrangement suggests that interactions between these domains may play a role in Ca2+ regulation (7). This possibility is strongly supported by the data that CBD12 movements are slower and occur at lower Ca2+ levels than for either CBD1 or CBD2. Synergistic interactions between the two domains have been documented in time-resolved experiments (26) in which a slow dissociation of Ca2+ was observed from the brain splice variant of CBD12 but not in CBD1 or CBD2. These two independent lines of evidence strongly suggest that the slow kinetics of Ca2+ dissociation (26) and the slow conformational transitions in CBD12 shown here are closely related events, even across splice variants.

The decrease in FRETE upon Ca2+ binding to CBD12 indicates an increase in distance between the fluorophores. In contrast, a study based on small-angle X-ray scattering analysis (7) suggests that within CBD12 a decrease in the maximal distance (Dmax; 120 ± 10 Å to 135 ± 10 Å) occurs upon binding of Ca2+. Dmax provides information on the maximum size of the protein without specifying the location at which these distances are obtained. Thus, FRET and small-angle X-ray scattering measurements reflect movements with different reference points and there is not necessarily a discrepancy in the two measurements.

The slow conformational changes of CBD12 observed upon removal of Ca2+ mirrors that of the full-length NCX and correlates with the deactivation times (∼5–10 s) of NCX activity measured electrophysiologically from patches from cardiac myocytes (2). The results suggest that NCX remains in an activated state for several seconds upon the removal of Ca2+, indicative of possible regulation over several beats. A persistent activation of NCX after reduction in intracellular Ca2+ in CHO cells has also been reported (39).

Overall, the results establish that interactions between the two CBDs take place within both the isolated conjunct CBDs and NCX. Possibly, as previously suggested (7), CBD2 exerts a stabilizing effect on the Ca2+-binding sites of CBD1 conferring high Ca2+ sensitivity. This hypothesis is supported by evidence that insertion of a linker between the CBDs decreases NCX sensitivity to Ca2+ (40) and abolishes the slow Ca2+ kinetics from the isolated CBD12 (26). Therefore, data obtained with isolated CBD1 and CBD2 are not representative of in vivo responses, and CBD12 is a more realistic model for in vitro studies.

In summary, our data provide evidence that NCX is a dimer in the plasma membrane, and binding of Ca2+ to CBD1 triggers a substantial decrease in the distance between the N-terminal portions of the large cytoplasmic loops of adjacent exchangers. These movements may be transduced to the adjoining TMS 5 to modulate NCX activity. Possibly other movements are transmitted between CBD2 and TMS 6. Interactions between CBD1 and CBD2 are clearly important in regulation of NCX as shown here and elsewhere (26, 40). The use of a fluorescent probe adjacent to TMS 6 for FRET measurements may be informative, and such experiments are being initiated.

Materials and Methods

Molecular Biology.

The generation of canine cardiac NCX-266CFP (NCXC) and NCX-266YFP (NCXY) has been previously described (16). Construction of the plasma membrane targeted CBDs is as described in the SI Materials and Methods.

FRET Measurements.

Xenopus laevis oocytes FluoPMS isolation and changes in FRETR measurements were conducted as described previously (17). FRETE was calculated using the gradual acceptor photobleaching technique (20). Additional information is presented in SI Materials and Methods. Solutions used for FRET measurements consist of (mM): 100 CsCl, 10 Hepes, 10 EGTA or N-(2-hydroxyethyl) ethylenediamine-N,N,N-triacetic acid (HEDTA), pH = 7 (using MES) and different free CaCl2 concentrations (calculated according to the WEBMAXC program (41) and validated with a Ca2+ electrode).

The relative expression of acceptor to donor as NCXY/NCXC ratio was calculated as fluorescence intensities of the acceptor and donor before and after acceptor bleaching, respectively. The ratio values were then converted into concentration ratios by normalizing to the value obtained from a construct with a fixed CFP/YFP stoichiometry, imaged with the same settings. For this purpose, the full-length exchanger with the fluorophores inserted at positions 266 and 467 was used, and an average FRETR of 8 was determined (7.97 ± 0.23, n = 64). The maximal FRETE (FRETmax) was deduced by fitting FRETE versus the NCXY/NCXC ratio with the equation FRETE = (FRETmax * r)/(1 + r), where r is the NCXY/NCXC concentration ratio (modified from ref. 23).

FRETE calculation for randomly distributed donors and acceptors were conducted using the Wolber and Hudson model (18, 21) as described in SI Materials and Methods.

Electrophysiology.

Outward NCX currents were recorded from oocytes in the inside-out configuration by using the giant patch technique, as previously described (5). Additional information is presented in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Debora Nicoll for constructive discussion on the manuscript. This work was supported by Grant HL49101 from the National Institutes of Health (to K.D.P.) and by a Laubisch endowment (to S.A.J.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1016114108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Philipson KD, et al. The Na+/Ca2+ exchange molecule: An overview. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;976:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hilgemann DW, Collins A, Matsuoka S. Steady-state and dynamic properties of cardiac sodium-calcium exchange. Secondary modulation by cytoplasmic calcium and ATP. J Gen Physiol. 1992;100:933–961. doi: 10.1085/jgp.100.6.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hilgemann DW, Matsuoka S, Nagel GA, Collins A. Steady-state and dynamic properties of cardiac sodium-calcium exchange. Sodium-dependent inactivation. J Gen Physiol. 1992;100:905–932. doi: 10.1085/jgp.100.6.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Besserer GM, et al. The second Ca2+-binding domain of the Na+ Ca2+ exchanger is essential for regulation: Crystal structures and mutational analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18467–18472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707417104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ottolia M, Nicoll DA, Philipson KD. Roles of two Ca2+-binding domains in regulation of the cardiac Na+-Ca2+ exchanger. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:32735–32741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.055434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaptal V, et al. Structure and functional analysis of a Ca2+ sensor mutant of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:14688–14692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C900037200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hilge M, Aelen J, Foarce A, Perrakis A, Vuister GW. Ca2+ regulation in the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger features a dual electrostatic switch mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14333–14338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902171106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hilge M, Aelen J, Vuister GW. Ca2+ regulation in the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger involves two markedly different Ca2+ sensors. Mol Cell. 2006;22:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson E, et al. Structure and dynamics of Ca2+-binding domain 1 of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in the presence and in the absence of Ca2+ J Mol Biol. 2008;377:945–955. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicoll DA, et al. The crystal structure of the primary Ca2+ sensor of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger reveals a novel Ca2+ binding motif. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21577–21581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600117200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu M, et al. Crystal structures of progressive Ca2+ binding states of the Ca2+ sensor Ca2+ binding domain 1 (CBD1) from the CALX Na+/Ca2+ exchanger reveal incremental conformational transitions. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:2554–2561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.059162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu M, Wang M, Nix J, Hryshko LV, Zheng L. Crystal structure of CBD2 from the Drosophila Na+/Ca2+ exchanger: Diversity of Ca2+ regulation and its alternative splicing modification. J Mol Biol. 2009;387:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stryer L. Fluorescence energy transfer as a spectroscopic ruler. Annu Rev Biochem. 1978;47:819–846. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.47.070178.004131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ottolia M, John S, Xie Y, Ren X, Philipson KD. Shedding light on the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1099:78–85. doi: 10.1196/annals.1387.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ren X, Nicoll DA, Galang G, Philipson KD. Intermolecular cross-linking of Na+–Ca2+ exchanger proteins: Evidence for dimer formation. Biochemistry. 2008;47:6081–6087. doi: 10.1021/bi800177t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ottolia M, John S, Ren X, Philipson KD. Fluorescent Na+-Ca+ exchangers: Electrophysiological and optical characterization. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3695–3701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610425200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ottolia M, Philipson KD, John S. Xenopus oocyte plasma membrane sheets for FRET analysis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C1519–C1522. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00435.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kenworthy AK, Edidin M. Distribution of a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein at the apical surface of MDCK cells examined at a resolution of <100 Å using imaging fluorescence resonance energy transfer. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:69–84. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zacharias DA, Violin JD, Newton AC, Tsien RY. Partitioning of lipid-modified monomeric GFPs into membrane microdomains of live cells. Science. 2002;296:913–916. doi: 10.1126/science.1068539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Munster EB, Kremers GJ, Adjobo-Hermans MJ, Gadella TW., Jr Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) measurement by gradual acceptor photobleaching. J Microsc. 2005;218:253–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2005.01483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolber PK, Hudson BS. An analytic solution to the Förster energy transfer problem in two dimensions. Biophys J. 1979;28:197–210. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(79)85171-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hilgemann DW. Unitary cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchange current magnitudes determined from channel-like noise and charge movements of ion transport. Biophys J. 1996;71:759–768. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79275-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bykova EA, Zhang XD, Chen TY, Zheng J. Large movement in the C terminus of CLC-0 chloride channel during slow gating. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:1115–1119. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mercier JF, Salahpour A, Angers S, Breit A, Bouvier M. Quantitative assessment of β1- and β2-adrenergic receptor homo- and heterodimerization by bioluminescence resonance energy transfer. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44925–44931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205767200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagai T, Yamada S, Tominaga T, Ichikawa M, Miyawaki A. Expanded dynamic range of fluorescent indicators for Ca(2+) by circularly permuted yellow fluorescent proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10554–10559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400417101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giladi M, Boyman L, Mikhasenko H, Hiller R, Khananshvili D. Essential role of the CBD1–CBD2 linker in slow dissociation of Ca2+ from the regulatory two-domain tandem of NCX1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:28117–28125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.127001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyman L, Mikhasenko H, Hiller R, Khananshvili D. Kinetic and equilibrium properties of regulatory calcium sensors of NCX1 protein. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6185–6193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwarzer A, Kim TS, Hagen V, Molday RS, Bauer PJ. The Na+/Ca2+-K+ exchanger of rod photoreceptor exists as dimer in the plasma membrane. Biochemistry. 1997;36:13667–13676. doi: 10.1021/bi9710232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fuster D, Moe OW, Hilgemann DW. Steady-state function of the ubiquitous mammalian Na/H exchanger (NHE1) in relation to dimer coupling models with 2Na/2H stoichiometry. J Gen Physiol. 2008;132:465–480. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sitte HH, Farhan H, Javitch JA. Sodium-dependent neurotransmitter transporters: Oligomerization as a determinant of transporter function and trafficking. Mol Interv. 2004;4:38–47. doi: 10.1124/mi.4.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao J, et al. Interaction between Arabidopsis Ca2+/H+ exchangers CAX1 and CAX3. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4605–4615. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804462200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farhan H, Freissmuth M, Sitte HH. Oligomerization of neurotransmitter transporters: A ticket from the endoplasmic reticulum to the plasma membrane. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2006;175:233–249. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29784-7_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ottolia M, Philipson KD, John S. Conformational changes of the Ca2+ regulatory site of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger detected by FRET. Biophys J. 2004;87:899–906. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.043471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levitsky DO, Nicoll DA, Philipson KD. Identification of the high affinity Ca2+-binding domain of the cardiac Na+-Ca2+ exchanger. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22847–22852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xie Y, Ottolia M, John SA, Chen JN, Philipson KD. Conformational changes of a Ca2+-binding domain of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger monitored by FRET in transgenic zebrafish heart. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C388–C393. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00178.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsuoka S, et al. Regulation of the cardiac Na+-Ca2+ exchanger by Ca2+. Mutational analysis of the Ca2+-binding domain. J Gen Physiol. 1995;105:403–420. doi: 10.1085/jgp.105.3.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kimura J, Noma A, Irisawa H. Na-Ca exchange current in mammalian heart cells. Nature. 1986;319:596–597. doi: 10.1038/319596a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wei SK, Quigley JF, Hanlon SU, O'Rourke B, Haigney MC. Cytosolic free magnesium modulates Na/Ca exchange currents in pig myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53:334–340. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00501-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reeves JP, Condrescu M. Allosteric activation of sodium-calcium exchange activity by calcium: Persistence at low calcium concentrations. J Gen Physiol. 2003;122:621–639. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ottolia M, Nicoll DA, John S, Philipson KD. Interactions between Ca2+ binding domains of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger and secondary regulation. Channels (Austin) 2010;4:159–162. doi: 10.4161/chan.4.3.11386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patton C, Thompson S, Epel D. Some precautions in using chelators to buffer metals in biological solutions. Cell Calcium. 2004;35:427–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.