Abstract

Vibrio vulnificus is a food-borne bacterial pathogen associated with 1% of all food-related deaths, predominantly because of consumption of contaminated seafood. The ability of V. vulnificus to cause disease is linked to the production of a large cytotoxin called the “multifunctional-autoprocessing RTX” (MARTXVv) toxin, a factor shown here to be an important virulence factor by the intragastric route of infection in mice. In this study, we examined genetic variation of the rtxA1 gene that encodes MARTXVv in 40 V. vulnificus Biotype 1 strains and found four distinct variants of rtxA1 that encode toxins with different arrangements of effector domains. We provide evidence that these variants arose by recombination either with rtxA genes carried on plasmids or with the rtxA gene of Vibrio anguillarum. Contrary to expected results, the most common rtxA1 gene variant in clinical-type V. vulnificus encodes a toxin with reduced potency and is distinct from the toxin produced by strains isolated from market oysters. These results indicate that an important virulence factor of V. vulnificus is undergoing significant genetic rearrangement and may be subject to selection for reduced virulence in the environment. This finding would imply further that in the future on-going genetic variation of the MARTXVv toxins could result in the emergence of novel strains with altered virulence in humans.

Keywords: phylogeny, RTX, oyster

The gram-negative bacterial pathogen Vibrio vulnificus inhabits coastal waters including the US Gulf Coast. The pathogen causes gastroenteritis, primary septicemia, and necrotizing fasciitis and can be difficult to treat. The bacteria are particularly rapid growers in vivo and are highly invasive; thus death can occur as quickly as 24–48 h after ingestion (1, 2). In the United States from 1998–2008, 985 cases of V. vulnificus infection resulting in 91 deaths were reported to the Centers for Disease Control. Of these cases, 60% were caused by food-borne illness, particularly associated with the consumption of raw seafood (3). In fact, V. vulnificus accounts for 1% of all food-related deaths in the United States (4).

Numerous studies recently have described a V. vulnificus multifunctional-autoprocessing RTX toxin (MARTXVv) as having a major impact on virulence in mice (5–8). Toxins of the MARTX family are very large composite toxins. The 5,206-amino acid MARTXVv toxin as found in the two sequenced strains of V. vulnificus, Korean isolate CMCP6 and Taiwanese isolate YJ016 (9, 10), are 99% identical. Similar to all MARTX toxins, the majority of MARTXVv is comprised of conserved repeat regions at the N and C termini that are proposed to form a pore in the eukaryotic cell plasma membrane for translocation of the central portion of the secreted toxin to the cytosol (11). The central region includes a conserved cysteine protease domain (CPD) that is required for inositol hexakisphosphate-induced autoprocessing. After translocation, autoprocessing at leucine residues in unstructured regions between the effector domains results in release of each effector domain from the large toxin to the cytosol where they then are free to access cellular targets (12). An interesting aspect of MARTX toxins is that each bacterial species carries a unique repertoire of effector domains and thus a distinct array of potential cytotoxic activities (11). To date, MARTXVv has been associated with multiple cytotoxic and cytopathic activities including actin depolymerization, apoptosis, necrosis, induction of reactive oxygen species, and activation of caspase-1 (5–8, 13, 14).

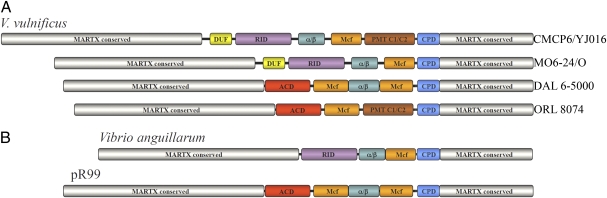

The central region of MARTXVv has been annotated previously (11). In addition to an inositol hexakisphosphate-inducible CPD (15), MARTXVv has five putative effector domains (Fig. 1). The first effector domain is a domain of unknown function (DUF) that has no functional homologs in the database but is found also in MARTX toxins from Xenorhabdus bovienii and Xenorhabdus nematophila (11). The amino acid sequence of the second effector domain is 86% identical to the Rho-inactivation domain (RID) of MARTXVc that has been demonstrated to stimulate cell rounding by inactivating cellular RhoGTPases (16). The third effector domain has homology to the αβ-hydrolase family of enzymes, although the enzymatic function and target of this enzyme are unknown (11). The fourth effector domain is 30% identical to a domain found within the Photorhabdus luminescens Makes Caterpillar Floppy (Mcf) toxins that are associated with Rac inactivation and apoptosis, although the function of this particular domain has not been characterized (11, 17). The fifth effector domain has homology to the C1 and C2 domains of Pasteurella multocida toxin (PMT C1/C2) (11). The C1 domain of P. multocida toxin and the PMT C1-like domain of MARTXVv are membrane localization domains (18, 19), but the function of the C2 domains has not been described in either toxin.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagrams of MARTX toxins. The gray and blue regions represent regions conserved in all MARTX family toxins that are required for translocation and autoprocessing of the central effector region. The color-coded centrally located effector domains are different in each MARTX toxin and are described further in the text. (A) MARTXVv variants from V. vulnificus Biotype 1 strains. Variants are referred to in the text by the first letter of the strain in which they were first recognized. (B) MARTX variants that probably served as donors in recombination events leading to the emergence of M-, D-, and O-type MARTXVv toxins.

In this study, we sought to determine if the MARTXVv toxin of V. vulnificus varies within the species and whether differences in the MARTXVv toxin structure are correlated with altered virulence. Overall, we find that MARTXVv is a significant virulence factor during food-borne infection and that there are four distinct variants of the toxin. In the United States the most prevalent form of the toxin in clinical-type V. vulnificus isolates is a variant with lower toxicity that arose by a recombination event. Because the prevailing toxin variant in US clinical isolates has reduced toxicity, our results suggest that future recombination events in this locus could result in acquisition of new domains that might increase toxicity resulting in novel strains with increased virulence in humans.

Results

Sequencing of rtxA1 Effector Domain Loci in Human and Oyster Isolates Reveals Four Variants of MARTXVv.

Although V. vulnificus strains CMCP6 and YJ016 have been fully sequenced, the strain most commonly used for studies of MARTXVv function is US clinical isolate MO6-24/O (5–7, 13, 14), a strain for which genome sequence has not yet been completed. Our attempts to study the toxin from MO6-24/O proved problematic because expected products from amplification of MO6-24/O chromosomal DNA using primers designed for the CMCP6 sequence often were either absent or ∼2 kb short (Fig. S1). Sequencing of PCR products revealed that the MO6-24/O products had 1,519 fewer nucleotides than CMCP6. Furthermore, the deduced protein sequence revealed that the toxin from MO6-24/O (here denoted as “MARTXVvM” or “M-type rtxA1”) would have only four effector domains and, as compared with the sequence from CMCP6 or YJ016 (here denoted as “MARTXVvC” or “C-type rtxA1”), is missing the PMT C1/C2 domain found in the fifth position (Fig. 1). This result demonstrated that the most common laboratory strains express distinct variants of the MARTXVv toxin.

To assess the natural distribution of the M-type versus C-type MARTXVv toxins among V. vulnificus isolates, the effector domain regions of the rtxA1 genes from 38 Biotype 1 V. vulnificus isolates were amplified by PCR, captured in a plasmid, and sequenced. The DNA corresponding to the conserved repeat regions was not sequenced to limit the overall size of the plasmid insert and to focus this study on the identification of effector domain arrangements. In addition to these 38 effector domain sequences, rtxA1 gene sequences for Biotype 1 strains CMCP6 (GenBank accession no. gi:27362712) (10), and YJ016 (Genbank accession no. gi:37509038) (9) were included in our analysis.

Among the human isolates, a C-type rtxA1 effector domain arrangement was found in 6 of 25 isolates (24%). By contrast, 17 of 25 (68%) carried an M-type gene, representing a significant enrichment in clinical strains for production of MARTXVvM (χ2 = 0.0026) (Table S1). Furthermore, annotation of a sequence deposited after this study was underway revealed that MARTXVvM also would be produced by the Biotype 3 strain 11028 (Genbank accession number gi:28558386) (20), indicating that this variant is produced by human isolates from two different biotypes.

In contrast to the clinical isolates, the C-type rtxA1 gene was most common (13 of 15) in US market oyster isolates. Thus, the prevalence of the M-type rtxA1 gene among US clinical isolates could not be explained by increased presence in the environment, because the C-type variant actually is enriched in the environment (χ2 < 0.0001). However, because of limitations of the strain collection, we cannot rule out temporal changes in V. vulnificus populations across seasons or years; most of our market oyster isolates are from 1998–1999, whereas our human isolates are from 1994–1998 (Table S1).

In addition to the C-type and M-type variants, two additional MARTXVv variants were identified. Interestingly, both these variants acquired an actin-crosslinking domain (ACD), an effector domain that introduces isopeptide bonds into actin, resulting in depolymerization of the cytoskeleton (21). The first variant was termed “MARTXVvO,” or “O-type rtxA1,” after strain ORL 8074 in which it was first identified; this variant also was identified in market oyster strain 98–783 DP-A1. In this variant the ACD is followed by Mcf and PMT C1/C2 domains, a MARTX effector domain arrangement not previously identified in any other species (Fig. 1).

The fourth variant was termed “MARTXVvD,” or “D-type rtxA1,” after strain DAL 6–5000 in which it was identified. In this variant the ACD is followed by Mcf, the αβ-hydrolase, and a second copy of the Mcf. This same effector-domain arrangement was identified previously in a copy of rtxA carried on pR99 present in the Biotype 2 V. vulnificus strain CECT4999 (Fig. 1) (21, 22). However, strain DAL 6–5000 does not have any plasmids (23), so MARTXVvD must represent a chromosomal copy. In support of this notion, CECT4999 recently was reported to have a second copy of the rtxA1 gene on the chromosome (Genbank accession no. gi:22132945) (20), and this variant also had the D-type effector domain arrangement. These data thus demonstrate that the D-type variant is not exclusive to Biotype 2 or to carriage on plasmids but also is present on the chromosome and in human clinical Biotype 1 isolates.

All MARTXVv Variant Types Are Found in Clinical MLST Lineage I.

Although the difference in the distribution of M-type rtxA1 in human versus environmental isolates was significant, we speculated this bias may not be caused specifically by selection for variation of the MARTXVv itself but rather by an historical event in which a strain more prone to cause infection underwent a genetic rearrangement in the rtxA1 gene. However, we found no correlation of a specific MARTXVv variant with other putative virulence markers (Table S1). In fact, MARTXVv M-type clinical isolates included strains with B- or AB-type rRNA sequences, type 1 and type 2 vvhA genes, and C- and E-type vcg genes. Only six of the isolates were positive for the vvpdh variant of pilF. Similarly, the MARTXVvC type isolates were distributed among rRNA, vvhA, and vcg types, and only one of the isolates was positive for vvpdh.

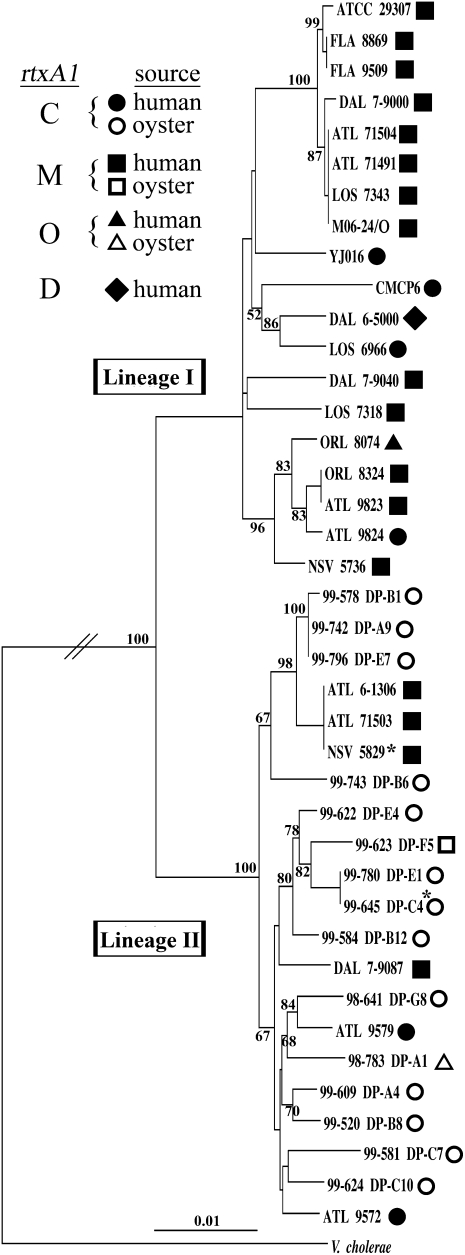

To test if the overall genome backbone accounted for clinical strains regardless of the MARTXVv toxin, we performed a 10-locus multilocus sequence typing (MLST) phylogeny. In concordance with previous studies (24, 25), the Biotype 1 strains split into two lineages (Fig. 2). Nineteen of 25 clinical strains derived from lineage I, which has been described as a virulence-conferring lineage (25). All four MARTXVv variants were represented in this lineage. Also in accordance with previous findings (25), all the oyster isolates clustered to lineage II with M-, C-, and O-type MARTXVv toxins represented. Thus, although it is possible that selection for the M-type toxin represents selection in humans, it is deemed more likely that the overall genomic background of the bacterium carrying the MARTXVv toxin gene has greater influence and that within this background all MARTXVv variants can contribute to human infection.

Fig. 2.

Neighbor-joining tree of all strains used in this study derived from a 10-locus MLST CLUSTALW alignment. A similar MLST profile was derived from the V. cholerae N16961 complete genome and was used as a divergent sequence to root the tree. Shapes as described in the legend refer to the effector domain region of the rtxA1 gene determined by nucleotide sequencing. Filled shapes are human isolates; open shapes are market oyster isolates. Bootstrap confidence values from 1,000 replicates are shown at branch points. Asterisks at 99–645 DP-C4 and NSV 5829 indicate these sequences include point mutations that introduce a stop codon in the ORF. Detailed strain descriptions are given in Table S1.

M-type rtxA1 Arose from C-type rtxA1 by Homologous Recombination, Not by Deletion.

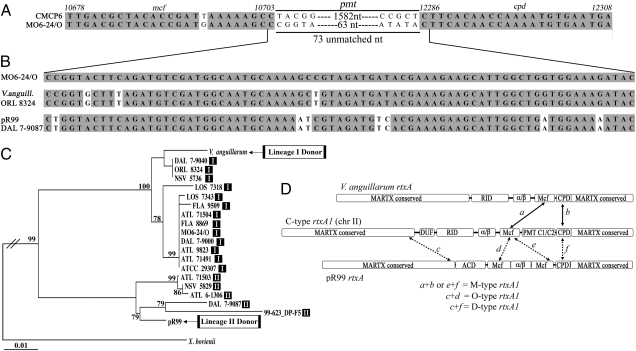

Based on the structure of M-type toxin genes within groups of C-type genes (Fig. 1), we speculated that M-type toxins arose by a deletion event that eliminated gene sequences for the PMT C1/C2. However, attempts to identify the deletion point in either the DNA or protein sequence were unsuccessful. In fact, 73 nucleotides are not accounted for in the M-type rtxA1 gene sequences between the 5′ and 3′ points of sequence divergence from the C-type gene (Fig. 3A). The 73-nucleotide sequence plus one nucleotide on each side (75 total) from the MO6-24/O sequence was used as query to search the nonredundant nucleotide database using BLASTN (Fig. 3B). The most significant hit (72 of 75 nucleotides) was the rtxA gene from Vibrio anguillarum, a pathogen of fish and shellfish. There was an additional significant hit (68 of 75 nucleotides) in the pR99 rtxA gene plus three additional plasmid-borne rtxA genes with sequences identical to the pR99 sequence.

Fig. 3.

Alignment of the portions of the rtxA1 gene from MO6-24/O and CMCP6 that encode the Mcf effector domain and the CPD. (A) A 1,519-bp deletion could not be identified because of 73 unmatched nucleotides in the MO6-24/O that do not derive from any part of the absent pmt locus. (B and C) Alignment of unmatched sequence from MO6-24/O and neighbor-joining tree of a 593-bp nucleotide sequence representing the 73 nucleotides plus 260 nucleotides on each side with potential rtxA donor sequences from V. anguillarum and the V. vulnificus plasmid pR99 and with other V. vulnificus strains more closely related to the donor sequences (note the differences in nucleotide polymorphisms in strains from different lineages). Boxes in the tree indicate the MLST lineage to which the strain is assigned (Fig. 2). Bootstrap confidence values from 1,000 replicates are shown at branch points. The rtxA gene sequence from X. bovienii, which also has an mcf–cpd junction in its rtxA gene (11), was used to root tree. (D) Schematic representation of how novel variants arose by recombination with V. anguillarum and plasmid rtxA genes.

We next surmised that the M-type rtxA1 gene arose not by deletion of nucleotides but rather by homologous recombination involving a C-type rtxA1 gene with either V. anguillarum rtxA or a V. vulnificus plasmid rtxA. Because recombination necessarily would involve DNA flanking the region, a phylogenetic tree using a 593-nucleotide sequence tag (the 73-nucleotide intervening sequence flanked by 260 nucleotides on each side) was constructed. Surprisingly, the M-type sequences from lineage I all clustered with V. anguillarum, whereas the lineage II sequences all clustered with the plasmid rtxA sequence (Fig. 3C). Indeed, a 100% match for the 73-bp sequence was identified within each group (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that the loss of the PMT C1/C2 effector from M-type toxins occurred not by a deletion but by at least two independent homologous recombination events involving distinct DNA donors (Fig. 3D). Assessment of sequence divergence across the entire effector domain regions further suggests that recombination with rtxA genes on plasmids may have occurred multiple times within lineage II (Fig. S2).

Emergence of the acd+ V. vulnificus rtxA1 Genes.

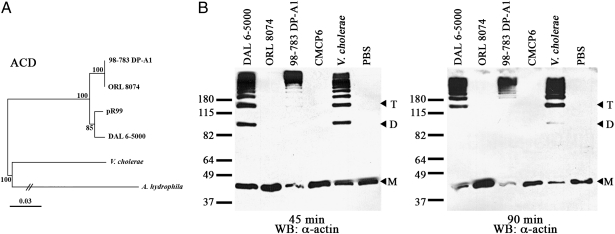

The two novel O-type and D-type MARTXVv toxins both acquired an ACD effector domain that had been mapped previously within the rtxA of pR99, Aeromonas hydrophila MARTXAh, and Vibrio cholerae MARTXVc (21). A phylogenetic tree of a 1,308-bp region of rtxA that encodes for ACD revealed a close match (97–98% nucleotide sequence identity) of the acd genes from V. vulnificus rtxA1 variants with the pR99 acd sequences but not with the acd sequences from V. cholerae or A. hydrophila (Fig. 4A). This result suggests that an acd+ rtxA gene on a plasmid is the likely source of the genetic sequences. The two different arrangements arise by recombination in different regions of the gene (Fig. 3D). The D-type was found to have acquired the entire effector domain region, whereas the O-type arose from a recombination involving the first mcf effector domain sequence of pR99 and sequences upstream of the effector domain region, thereby retaining its original pmt and cpd regions, which were found to align closely with the pmt region from CMCP6. A similar event appears to have occurred at least twice, one giving rise to ORL 8074 (lineage I) and the other to 98–783 DP-A1 (lineage II).

Fig. 4.

(A) Neighbor-joining tree of a 1,308-bp region corresponding to the acd of rtxA genes from various species and plasmids. Bootstrap confidence values from 1,000 replicates are shown at the branch points. (B) Anti-actin Western blots of HeLa cell lysates after incubation with indicated bacterial strains for indicated times. M, monomeric actin; D, dimeric actin; T, trimeric actin.

Because these variants acquired the ACD, the strains were tested for gain of actin crosslinking activity. When incubated with HeLa cells, DAL 6–5000 showed actin crosslinking activity comparable to that seen previously with V. cholerae at 45 and 90 min, and 98–783 DP-A1 showed greater activity than V. cholerae (Fig. 4B). By contrast, the lineage I clinical strain ORL 8074 did not have actin crosslinking activity. These results suggest ORL 8074 strain may have a mutation in the rtxA gene outside the region that was sequenced or a mutation in genes or promoter regions required for regulation, maturation, or secretion of the toxin. Overall, these data demonstrate that recombination can lead to acquisition of additional effector domains producing toxins with novel catalytic activities.

Virulence Properties of M- and C-Type Strains.

Because the rtxA1 gene is an important virulence gene, it was considered that changes to the gene structure could result in quantitative differences in pathogenicity. Because consumption of contaminated food is a major source of clinical infection, we sought to the study the relevant intragastric route of infection. Previous studies showed that V. vulnificus MO6-24/O is lethal to antibiotic-treated mice when inoculated intragastrically at a dose of 109 cfu. At this same dose, 80% of mice survived challenge with an isogenic ΔrtxA1 mutant (5). However, because of the high dose of the wild-type strain required for infectivity, the quantitative contribution of rtxA1 to infection cannot be determined in the antibiotic-fed mice.

Previous studies with small intestinal pathogens V. cholerae and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis have established that use of ketamine as an anesthetic at the time of bacterial inoculation enhances susceptibility of mice to small intestine infection, facilitating assessment of LD50 without use of antibiotics (26, 27). In accordance with these findings, use of ketamine changed the survival rate of mice inoculated with 106 cfu V. vulnificus CMCP6 from 83% to 0% (Table S2). Whole-animal imaging confirmed that mice inoculated with V. vulnificus under ketamine anesthesia developed an intestinal infection, and the increased lethality was not caused by inadvertent lung infection (Fig. S3).

To test the influence of toxin variation on virulence, C57BL/6 5- to 6-wk-old mice injected with ketamine/xylazine were inoculated orally with 106 cfu of three C-type and three M-type human isolates. The acd+ strains were not tested because, as discussed earlier, data suggested ORL 8074 may not produce an active MARTXVv toxin and DAL 6–5000 was found previously to be avirulent by s.c. infection (23). The six selected strains showed a range of virulence: high virulence for lineage I laboratory-passaged clinical isolates CMCP6 and MO6-24/O (0–10% survival); intermediate virulence for lineage I clinical isolates LOS 6966 and FLA 9509 (50–83% survival); and low virulence for lineage II strains ATL 71503 and ATL 9579 (100% survival) (Table S2). Each pair included C- and M-type rtxA1 strains, indicating that virulence of wild-type strains in mice is broadly variable and probably depends on many factors, so there was no direct correlation between overall intragastric virulence and a specific type of MARTXVv.

As an alternative strategy that would control for strain-to-strain variation, the overall contribution to virulence of the rtxA1 gene was assessed by comparing the LD50 of wild-type strains with the virulence of ΔrtxA1 mutants constructed in isogenic backgrounds. The deletion of rtxA1 from CMCP6 resulted in a 2,600-fold increase in LD50 when inoculated intragastrically (Table 1). By contrast, the deletion of rtxA1 from MO6-24/O resulted in only a 180-fold increase in LD50, a 14-fold reduced contribution to virulence compared with rtxA1 of CMCP6. To test if the additional PMT C1/C2 domain of MARTXVvC was the cause of the increased toxin potency, a hybrid version of the rtxA1 gene in CMCP6 was constructed by recombining the linked mcf-cpd gene sequences from MO6-24/O into the rtxA1 gene of CMCP6, similar to the exchange that occurred naturally to generate the M-type rtxA1 strains. This recombination generated a CMCP6Δpmt mutant that had a 54-fold reduced virulence compared with the wild-type strain CMCP6. This result confirms in an isogenic background that the PMT C1/C2 domain of MARTXVvC contributes to increased virulence of CMCP6 compared with MO6-24/O and the genetic exchange to remove the pmt effector produced a toxin with reduced potency in mice.

Table 1.

Intragastric LD50 for various V. vulnificus strains and isogenic mutants

| Inoculated strain | n* | LD50 | Fold change compared with isogenic wild type |

| CMCP6 | 10 | 2.4 × 104 | — |

| CMCP6ΔrtxA1 | 10 | 6.3 × 107 | 2600× ↑ |

| CMCP6Δpmt | 10 | 1.3 × 106 | 54× ↑ |

| MO6-24/O | 10 | 1.8 × 105 | — |

| MO6-24/OΔrtxA1 | 10 | 3.2 × 107 | 180× ↑ |

*Survival data are pooled from two experiments conducted with five mice per dosage group for each strain.

Discussion

Tracking the environmental source of V. vulnificus strains that cause food-borne infection of humans has proven difficult. Previous studies linking clinical strains to genetic sequences including 16S rRNA type, vvhA, vcg, and vvpdh ultimately have concluded that variation in these factors is not exclusive to clinical strains (Table S1) (28). There is a strong correlation between a lineage I MLST and human strains, but human isolates also derive from within lineage II (Fig. 2) (25). In this study, using a quantitative infection strategy, we show that MARTXVv toxin is a significant virulence factor by the intragastric route of infection. Previous studies had linked the rtxA1 gene to wound-induced infection (7, 8). We sought to understand better the distribution of this important factor across V. vulnificus strains by undertaking a gene-sequencing approach. To our surprise, our sequencing revealed the rtxA1 gene is subject to recombination events either with rtxA genes on circulating plasmids or with rtxA genes from other marine pathogens. These recombination events resulted in novel MARTXVv toxin variants, all of which are represented in the virulence-associated lineage I. The enrichment of human isolates in lineage I occurred irrespective of the structure of the MARTXVv toxin. This finding supports the idea that human virulence potential is conferred not by the structure of the toxin but by the genome on which it is carried. Within lineage II, similar recombination events have occurred in both oyster and human isolates, although fewer human isolates are found in this group in general. Overall we found no evidence of cross-clade rtxA1 gene exchange, indicating that recombination events with rtxA genes from other sources led to increased diversity of V. vulnificus isolates.

In the isolates analyzed for this study, the variant represented by MO6-24/O, which was rare in the oyster isolates, was the most common in human isolates. These data thus further support previous findings (24, 25) that the Biotype 1 strains that infect humans are not the strains that are most common in the oysters; here we also find that they predominantly produce a different variant of the primary virulence toxin.

In contrast to expectations, this most common variant actually was less potent to mice than the likely precursor toxin represented in the sequenced strain CMCP6. Therefore, a significant question remaining is whether, in addition to an unknown factor that in lineage I strains confers increased fitness for infection of human, these strains are under selective pressure for reduced MARTXVv toxicity. If so, then lineage I V. vulnificus might be highly infectious to an aquatic host, possibly even oysters, and thus there is selection for a lower-potency toxin to facilitate persistence of the bacterial population in asymptomatic animals. Alternatively, the PMT C1/C2 effector domain simply may be dispensable for lineage I strains in the environment and was lost by an unselected recombination event. However, if PMT C1/C2 were important for successful colonization of oysters, the loss of PMT C1/C2 from the lineage I strains might have produced a strain that competes poorly with the lineage II strains, explaining the relatively low frequency of lineage I V. vulnificus in oysters.

A final important finding of our work is the evidence of on-going recombination in the environment within the clinical-type lineage that includes acquisition of new effector domains such as the ACD and novel toxin arrangements. Over time, these events could lead to the emergence of additional rtxA1 variants. Indeed, analysis of rtxA genes in a variety of Gram-negative pathogens revealed at least 10 different effector domains carried by this class of toxin (11). Thus, given the reduced potency of the M-type strains currently prevalent in the United States, it is possible that the MARTXVv will gain new effector domains in the lineage I genomic background that could reverse the current trend toward low-potency toxin strains and instead produce a hypervirulent strain, resulting in an increased incidence of severe V. vulnificus disease in the future.

Materials and Methods

PCR and Sequencing Of Effector Domain Regions.

Chromosomal DNA was used as template in PCR with primers as detailed in Table S3. PCR products amplified by LongAmp Taq polymerase (New England Biolabs) were captured on a plasmid using the Invitrogen TOPO XL PCR cloning kit. Resulting plasmids were confirmed to have an insert by altered mobility of supercoiled plasmid during agarose gel electrophoresis. The entire insert of one clone from each V. vulnificus strain was sequenced at the Northwestern University Genomics Core Facility using primers designed to the known CMCP6 sequence or by primer walking. The sequence was assembled using MacVector Assembler Package 10.5.1. Sequences were deposited with GenBank accession numbers HQ391952–HQ391988.

Phylogenetic Analysis.

MLST sequences were downloaded as concatenated sequences from www.pubmlst.org/vvulnificus, except for CMCP6, YJ016, and V. cholerae N16961, which were derived from published genome sequences, and 99–578 DP-B1 and ATCC 29307, which were determined by PCR and sequencing using methods as described by Bisharat et al. (24). Novel MLST sequences were designated ST82 and ST83 in the pubmlst.org database. rtxA1, and concatenated MLST sequences were aligned using CLUSTALW and the phylogeny determined with PHYLIP using the Workbench 3.2 interface at the San Diego Supercomputer Center. Neighbor-joining trees for publication were prepared from the Newick output using Dendroscope 2.7.4 (29–33). The bootstrap confidence values (1,000 replicates) were determined using MacVector 10.5.1 sequence alignment software package.

Generation of ΔrtxA1 and Δpmt Strains.

The sacB-counterselectable plasmids carrying the desired rtxA1 gene arrangements were delivered to a rifampicin-resistant isolate of CMCP6 by conjugation. Isolates with integrated plasmid were selected for by gain of chloramphenicol resistance, and subsequent deletion mutants arising by double homologous recombination were selected on sucrose medium. Single colonies with the desired gene arrangement were confirmed by PCR. The rtxA1 mutant of MO6-24/O was a gift from Paul Gulig (University of Florida, Gainesville, FL).

Mouse Virulence Assays.

Mouse infections were performed by protocols approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee using C57BL/6 mice and methods identical to those previously described for infection using V. cholerae (26). Mice were killed at the point of severe morbidity and counted as nonsurvivors. LD50 was calculated by the method of Reed and Muench (38).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jessica Jones and Angelo DePaola for the human and oyster V. vulnificus isolates and Paul Gulig for strains CMCP6, MO6-24/O, and MO6-24/OΔrtxA1. We thank Mark Mandel for his input on phylogeny and Jessica Queen for assistance with mouse studies. Work on V. vulnificus was initiated as a Developmental Project Subcontract from the Great Lakes Regional Center of Excellence [National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant U54 AI057153]. This study was supported by an Investigators in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and by NIH Grants RO1 AI051490 and R21 AI072461 ( to K.J.F.S.). H.-G.J. was funded by postdoctoral fellowship KRF-2009-352-F00037 from the Korean Research Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. HQ391952–HQ391988).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1014339108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Gulig PA, Bourdage KL, Starks AM. Molecular pathogenesis of Vibrio vulnificus. J Microbiol. 2005;43(Spec No):118–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strom MS, Paranjpye RN. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of Vibrio vulnificus. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:177–188. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC . 2010. National Case Surveillance: Cholera and Other Vibrio Illness Survillance System: Annual Summaries of Vibrio illnesses. Available at: www.cdc.gov. Accessed November 23, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mead PS, et al. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:607–625. doi: 10.3201/eid0505.990502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung KJ, et al. RtxA1-induced expression of the small GTPase Rac2 plays a key role in the pathogenicity of Vibrio vulnificus. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:97–105. doi: 10.1086/648612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim YR, et al. Vibrio vulnificus RTX toxin kills host cells only after contact of the bacteria with host cells. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:848–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JH, et al. Identification and characterization of the Vibrio vulnificus rtxA essential for cytotoxicity in vitro and virulence in mice. J Microbiol. 2007;45:146–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu M, Alice AF, Naka H, Crosa JH. The HlyU protein is a positive regulator of rtxA1, a gene responsible for cytotoxicity and virulence in the human pathogen Vibrio vulnificus. Infect Immun. 2007;75:3282–3289. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00045-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen CY, et al. Comparative genome analysis of Vibrio vulnificus, a marine pathogen. Genome Res. 2003;13:2577–2587. doi: 10.1101/gr.1295503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim YR, et al. Characterization and pathogenic significance of Vibrio vulnificus antigens preferentially expressed in septicemic patients. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5461–5471. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5461-5471.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satchell KJ. MARTX, multifunctional autoprocessing repeats-in-toxin toxins. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5079–5084. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00525-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egerer M, Satchell KJ. Inositol hexakisphosphate-induced autoprocessing of large bacterial protein toxins. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000942. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee BC, Choi SH, Kim TS. Vibrio vulnificus RTX toxin plays an important role in the apoptotic death of human intestinal epithelial cells exposed to Vibrio vulnificus. Microbes Infect. 2008;10:1504–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toma C, et al. Pathogenic Vibrio activate NLRP3 inflammasome via cytotoxins and TLR/nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-mediated NF-kappa B signaling. J Immunol. 2010;184:5287–5297. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen A, et al. Mechanistic and structural insights into the proteolytic activation of Vibrio cholerae MARTX toxin. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:469–478. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheahan KL, Satchell KJ. Inactivation of small Rho GTPases by the multifunctional RTX toxin from Vibrio cholerae. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:1324–1335. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00876.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vlisidou I, et al. Drosophila embryos as model systems for monitoring bacterial infection in real time. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000518. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geissler B, Tungekar R, Satchell KJ. Identification of a conserved membrane localization domain within numerous large bacterial protein toxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:5581–5586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908700107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamitani S, et al. Characterization of the membrane-targeting C1 domain in Pasteurella multocida toxin. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:25467–25475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.102285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roig FJ, Gonzalez-Candelas F, Amaro C. The domain organization and evolution of MARTX toxin in Vibrio vulnificus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010 doi: 10.1128/AEM.01806-10. 10.1128/AEM.01806-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Satchell KJ. Actin crosslinking toxins of Gram-negative bacteria. Toxins (Basel) 2009;1:123–133. doi: 10.3390/toxins1020123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee CT, et al. A common virulence plasmid in Biotype 2 Vibrio vulnificus and its dissemination aided by a conjugal plasmid. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:1638–1648. doi: 10.1128/JB.01484-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DePaola A, et al. Analysis of Vibrio vulnificus from market oysters and septicemia cases for virulence markers. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:4006–4011. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.7.4006-4011.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bisharat N, et al. Hybrid Vibrio vulnificus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:30–35. doi: 10.3201/eid1101.040440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen AL, Oliver JD, DePaola A, Feil EJ, Boyd EF. Emergence of a virulent clade of Vibrio vulnificus and correlation with the presence of a 33-kilobase genomic island. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:5553–5565. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00635-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olivier V, Queen J, Satchell KJ. Successful small intestine colonization of adult mice by Vibrio cholerae requires ketamine anesthesia and accessory toxins. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schiano CA, Bellows LE, Lathem WW. The small RNA chaperone Hfq is required for the virulence of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2010;78:2034–2044. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01046-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanjuán E, Fouz B, Oliver JD, Amaro C. Evaluation of genotypic and phenotypic methods to distinguish clinical from environmental Vibrio vulnificus strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:1604–1613. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01594-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins DG, Bleasby AJ, Fuchs R. CLUSTAL V: Improved software for multiple sequence alignment. Comput Appl Biosci. 1992;8:189–191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP–Phylogeny Inference Package (Version 3.2) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huson DH, et al. Dendroscope: An interactive viewer for large phylogenetic trees. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:460. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Z, Schwartz S, Wagner L, Miller W. A greedy algorithm for aligning DNA sequences. J Comput Biol. 2000;7:203–214. doi: 10.1089/10665270050081478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reed LJ, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.