Abstract

Mutations of BRAF are found in ∼45% of papillary thyroid cancers and are enriched in tumors with more aggressive properties. We developed mice with a thyroid-specific knock-in of oncogenic Braf (LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre) to explore the role of endogenous expression of this oncoprotein on tumor initiation and progression. In contrast to other Braf-induced mouse models of tumorigenesis (i.e., melanomas and lung), in which knock-in of BrafV600E induces mostly benign lesions, Braf-expressing thyrocytes become transformed and progress to invasive carcinomas with a very short latency, a process that is dampened by treatment with an allosteric MEK inhibitor. These mice also become profoundly hypothyroid due to deregulation of genes involved in thyroid hormone biosynthesis and consequently have high TSH levels. To determine whether TSH signaling cooperates with oncogenic Braf in this process, we first crossed LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre with TshR knockout mice. Although oncogenic Braf was appropriately activated in thyroid follicular cells of these mice, they had a lower mitotic index and were not transformed. Thyroid-specific deletion of the Gsα gene in LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre/Gnas-E1fl/fl mice also resulted in an attenuated cancer phenotype, indicating that the cooperation of TshR with oncogenic Braf is mediated in part by cAMP signaling. Once tumors were established in mice with wild-type TshR, suppression of TSH did not revert the phenotype. These data demonstrate the key role of TSH signaling in Braf-induced papillary thyroid cancer initiation and provide experimental support for recent observations in humans pointing to a strong association between TSH levels and thyroid cancer incidence.

Keywords: Ras, G protein, pax8

Thyroid follicular cells are among a select group of cell types, which includes other endocrine cell lineages, melanocytes, and Schwann cells, in which the second messenger cAMP helps promote DNA synthesis and cell proliferation. In thyroid cells this pathway is engaged via constitutive and ligand-induced activation of the TSH receptor (TSHR), which, however, requires concomitant activation of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling for growth to ensue (1–3). It is therefore fitting that distinct subtypes of thyroid neoplasms are associated with oncogenes encoding effectors of the TSH–TSH receptor–adenylyl cyclase pathway (i.e., TSHR and GNAS) (4, 5) or with proteins that signal along canonical receptor tyrosine kinase pathways. Thus, rearrangements of genes encoding the receptor tyrosine kinases RET or NTRK, as well as point mutations of all three RAS genes and of the serine kinase BRAF, are found in a mutually exclusive manner in papillary thyroid cancers (PTC), the most prevalent form of the disease (6–8). The activating point mutation BRAFT1799A, which encodes for BRAFV600E, is the most common genetic abnormality in papillary thyroid cancer and constitutively activates the MEK–ERK pathway. Thyroid cancers with BRAF mutations have distinctive pathological and phenotypic features: i.e., they are more frequently invasive, have higher recurrence rates, are relatively refractory to radioiodine therapy, and have a higher disease-specific mortality (9–11).

Mutations of BRAF are also found with high frequency in benign nevi and in melanomas (12, 13) and to a lesser extent in lung cancers (14, 15). Conditional endogenous expression of mutant Braf in mice with a latent BrafT1799A allele results in melanocyte hyperplasia and development of nevi, which show features consistent with senescence (16, 17). The two mouse models in which expression of BrafV600E at physiological levels was conditionally targeted to melanocytes differed in one respect: Melanoma development was encountered in only one of them without additional genetic manipulations (16), whereas in the other metastatic melanoma developed only when the tumor suppressor Pten was also genetically inactivated (17). Similarly, endogenous expression of BrafV600E in lung alveolar epithelial cells is insufficient by itself to induce lung cancers (18).

Here we examined the effects of physiological levels of oncogenic Braf expression on mouse thyrocyte tumorigenesis. As opposed to that seen in other lineages, these animals developed invasive papillary thyroid cancers with very short latency. The penetrance, extent, and latency of these cancers depended on the presence of an intact TSH signaling pathway, primarily at the time of tumor initiation. These findings may help explain the increased risk of thyroid cancer conferred by higher TSH levels in patients with thyroid nodules, which has recently been reported in several epidemiological studies (19–21).

Results

To investigate the role of endogenous expression of BrafV600E in the pathogenesis of thyroid cancer we established mice with a thyrocyte-specific knock-in of the oncogene, by crossing LSL-BrafV600E mice, in which a latent Braf mutant allele can be activated by Cre recombinase through excision of a floxed STOP cassette, with TPO-Cre mice, which express Cre under the control of the human thyroid peroxidase (TPO) promoter (Fig. S1A). TPO is expressed in thyroid follicular cells starting at embryonic day (E)14.5. Recombination efficiency was not maximal until 7–10 d postnatally (Fig. S1B). LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre animals were born at the expected Mendelian frequency. However, they weighed ≈50% less than wild-type littermates by weaning (Fig. S2A).

Endogenous Expression of BrafV600E in Thyroid Tissue Induces Hypothyroidism.

Because overexpression of oncogenic effectors that activate MAPK has previously been shown to impair thyroid hormone production in vivo (22, 23), we first sought to determine whether the growth retardation was due to hypothyroidism. LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre mice were euthyroid at day 3 (Fig. S3B), yet by 5 wk of age serum TSH levels were ∼500-fold greater than those of age-matched wild-type (WT) littermates, and serum T4 levels were markedly decreased (Fig. S2B). Thyroglobulin (Tg), sodium iodide symporter (Nis), and Tpo mRNA levels were markedly down-regulated at 5 wk in LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre mice. The expression of TshR was also significantly inhibited (Fig. S2C). Pax8 mRNA, which encodes a key transcription factor that is required for expression of several thyroid-specific genes, was also decreased. Hence, endogenous expression of BrafV600E was sufficient to profoundly deregulate thyroid-specific gene expression and thyroid hormonogenesis.

Induction of Invasive PTCs by Oncogenic Braf.

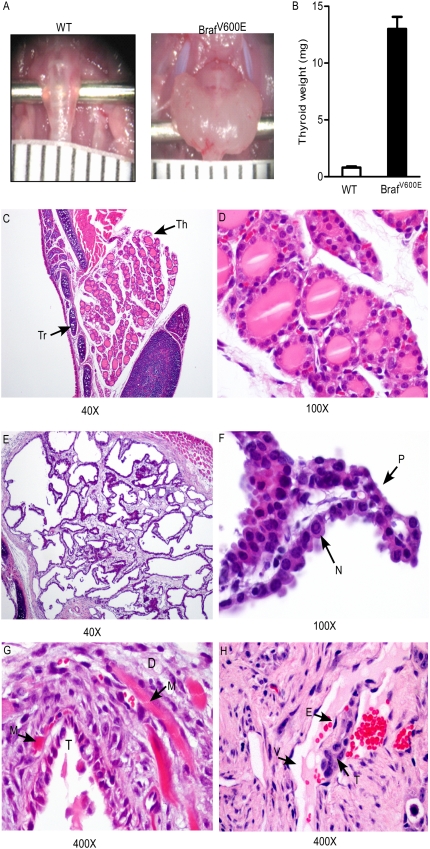

Braf activation led to the development of classic infiltrative PTC with complete penetrance by 5 wk (Fig. 1).The tumors, which encompassed the entire thyroid gland, had features characteristic of aggressive human PTC with papillae lined by tall cells, with increased number of mitoses, nuclear clearing, and pseudonuclear inclusions (Fig. 1F). The malignant phenotype was further established because tumor cells frequently invaded perithyroidal tissues (Fig. 1G). Thus, 8/12 (66%) PTCs invaded into surrounding skeletal muscle by 5 wk, and vascular invasion was commonly observed (Fig. 1H). There was no difference in the severity, penetrance, or latency of the disease between female and male mice.

Fig. 1.

Thyroid-specific activation of Braf leads to the development of thyroid cancer with short latency. (A) Gross anatomical images of wild-type and LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre thyroid glands from mice at 5 wk. (B) Thyroid weight is significantly increased in both male and female LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre mice compared with wild-type littermates. Bars represent mean ± SEM. (C–H) Representative H&E images from thyroid tissues of wild-type and LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre mice at 5 wk. (C and D) Low (40×) and high (100×) magnification, respectively, of normal thyroid lobe of a WT mouse. Thyroid follicles are filled with colloid. Arrows points to thyroid lobe (Th) and tracheal cartilage (Tr). (E) Magnification (40×) of markedly enlarged thyroid lobe in a LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre mouse. Thyroid architecture is disrupted, and no colloid material is evident. (F) Papillary formations (P) and nuclear pseudoinclusion (N). (Magnification, 100×.) (G) Malignant follicle (T) invading into surrounding skeletal muscle (M). Desmoplasia (D) is evident, indicative of muscle invasion. (H) Tumor cell thrombus (T) surrounded by endothelial cells (E) hanging in the lumen of a blood vessel (V).

Knockout of TshR or Gsα Impairs Braf-Induced PTC Development.

As TSH is a thyroid cell mitogen, we next examined whether TSH and Braf cooperated in the initiation of Braf-induced thyroid tumors. For this we crossed LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre with TshR-KO mice to genetically ablate TSH signaling. As Cre is driven by the TPO promoter in our model, and thyroid cells from TshR-KO mice have decreased Tpo expression (24), we confirmed that recombination efficiency of the targeted Braf gene locus was maintained in mice lacking TshR (Fig. S1C). Thyroid glands from TshR-KO mice were smaller and had hypotrophic thyroid follicles compared with WT littermates. By 3 wk, all LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre mice developed PTC (Fig. 2B). By contrast, genetic ablation of TSH signaling partially blocked Braf-induced thyroid growth (Fig. 2I). Thyroid glands from LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre/TshR-KO were smaller than those from LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre mice (Fig. 2I), and although the architecture of the follicles was distorted compared with that of TshR-KO thyroids, the histopathology was uniformly benign and lacked the characteristic nuclear features of PTC (Fig. 2D vs. 2C). They also exhibited a markedly lower mitotic index than LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre mice (Fig. 2H vs. 2F). However, by 9 wk thyroid cells of LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre/TshR-KO mice escaped the dependence upon TSH signaling and developed low-grade PTCs. The tumors were smaller, lacked the characteristic tall cell features seen in tumors with WT TshR, and were less invasive (Fig. 2 J and K). Hence, thyroid cells lacking TshR can be transformed by Braf after a longer latency and are phenotypically less aggressive.

Fig. 2.

Braf-induced PTC development requires TshR. (A–D) H&E images from representative thyroid sections of animals of the indicated genotype at 3 wk. Thyroids from LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre (B) mice are significantly increased in size compared with WT (A). LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre mouse thyroid (B) shows a florid PTC, which is highly cellular. (C) Thyroid lobe of a TshR-KO animal is markedly smaller than WT (A), but retains normal follicular structures. (D) Thyroid lobe of LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre/TshR-KO is comparatively larger than that of TshR-KO and has disrupted follicular architecture. The cells lack the characteristic nuclear features pathognomic of PTC. (E–H) Ki67 immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of representative thyroid lobes of the same animal groups. The mitotic index is markedly higher in the LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre thyroid (F) compared with WT (E). There are virtually no detectable Ki67-positive cells in the thyroid sections of TshR-KO (G) and LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre /TshR-KO (H) mice. (I) Thyroid weight of wild-type, TshR−/+, TshR−/−, LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre, LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre/TshR−/+, and LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre/TshR−/− mice at 3 wk. (J and K) Magnification (40× and 200×) of thyroid sections of LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre /TshR-KO mice at 9 wk of age. Note increase in size of thyroid in J compared with 3-wk-old animal (E). Magnification (200×) in K shows characteristic papillary structures lined by irregular nuclei; however, tumors were of lower grade and had no extrathyroidal invasion.

TSH-induced thyroid cell growth is mediated in part by TSHR activation of adenylyl cyclase via Gsα, the product of the Gnas gene. To further define the role of TSH signaling in thyroid tumor initiation by oncogenic Braf, we crossed LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre mice with Gnas-E1fl/fl mice, in which the targeted Gsα allele is inactivated by Cre-mediated recombination. There was no difference in the thyroid histology of Gnas-E1fl/fl/TPO-Cre mice compared with WT littermates. LSL-BrafV600E/Gnas-E1fl/fl/TPO-Cre developed smaller tumors (Fig. 3A) with greatly attenuated histological features (Fig. 3). Whereas Braf-induced PTCs in mice with intact Gsα had characteristic tall cells (Fig. 3D), their Gsα-null counterparts were cuboidal (Fig. 3E), with scant mitoses and few cells with nuclear clearing. These characteristics resemble indolent PTCs in humans, whereas LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre tumors displayed histological features of aggressive PTCs that often progress to poorly differentiated disease.

Fig. 3.

Loss of Gsα attenuates the phenotype of PTC induced by endogenous expression of BrafV600E. (A) Thyroid weight of wild-type, Gnas-E1fl/+/TPO-Cre, Gnas-E1fl/fl/TPO-Cre, LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre, LSL-BrafV600E/Gnas-E1fl/+/TPO-Cre, and LSL-BrafV600E/Gnas-E1fl/fl/TPO-Cre mice at 3 wk. Bars represent mean ± SEM. (B–E) Representative H&E-stained sections of thyroid tissue at 40× and 200× magnification of LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre and BrafV600E/TPO-Cre/Gnas-KO mice. (B) LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre tumors have dense cellularity, and the whole field is occupied by the carcinoma. (C) Thyroid section of LSL-BrafV600E/Gnas-E1fl/fl/TPO-Cre mouse shows areas with relatively preserved follicular structures (arrow) coexisting with a low-grade PTC. (Magnification, 40×.) (D) Areas of tall cell growth (arrow), characteristic of aggressive BRAF-positive PTCs in humans, are present only in the Gnas WT mice. (E) PTCs in LSL-BrafV600E/Gnas-E1fl/fl/TPO-Cre mice are composed of smaller papillae consisting of cuboidal cells (arrow).

Suppression of TSH Secretion Postnatally Does Not Prevent PTC Development or Block Disease Progression.

TshR signaling can also be dampened by suppressing pituitary secretion of the ligand through administration of a supraphysiological dose of levothyroxine (L-T4). We next examined whether TSH suppression, beginning soon after birth, could prevent or delay the development of PTC. At 3 d, thyroid glands of WT and LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre mice were indistinguishable histologically and had a comparable proliferative rate (Fig. S3A). Administration of exogenous L-T4 for 3 wk at a dose that completely suppressed TSH (Fig. S3E) did not prevent the onset or alter the characteristics of the Braf-induced PTCs and hence did not phenocopy TshR deletion (Fig. S3F). Moreover, treatment of LSL-BrafV600E /TPO-Cre mice with L-T4 for 3 wk beginning at 5 wk of age, when all had florid PTC, did not decrease the mitotic rate or alter the severity or progression of the Braf-induced PTCs.

Endogenous Expression of Oncogenic Hras Does Not Phenocopy Effects of Braf on Thyroid Hormone Biosynthesis or Tumorigenesis.

Mutations of NRAS and HRAS are common in human follicular-variant PTCs and follicular carcinomas (25, 26). Overexpression of HRASG12V also down-regulates expression of genes required for thyroid hormone biosynthesis in vitro (27), an effect that has been shown to be dose dependent (28). To determine whether endogenous expression of HrasG12V is sufficient to induce thyroid dysfunction and thyroid cell transformation, we crossed FR-HrasG12V mice, which have a latent Hras oncogenic allele expressed under the control of its native promoter, with TPO-Cre mice. Offspring were of normal weight compared with littermates, and serum levels of TSH and T4 were unaffected (Fig. S4A). Accordingly, there was also no difference in transcript abundance of thyroid-specific genes (Fig. S4B). In contrast to BrafV600E, endogenous expression of HrasG12V did not induce thyroid neoplasms through 12 mo of follow-up (29). To determine whether supraphysiological levels of TSH might cooperate with activated Hras to induce thyroid tumors we treated FR-HrasG12V/TPO-Cre mice with the goitrogen 6-propyl-2-thiouracil (PTU) for up to 20 wk. Despite significant increases in TSH and the development of benign goiters, none of the FR-HRasG12V/TPO-Cre mice developed thyroid cancer or showed a significant increase in Ki67 staining relative to controls (Fig. S5).

Selective MEK Inhibitor PD325901 Reduces Growth of Braf-Induced PTC.

Human thyroid cancer cell lines harboring BRAF mutations are sensitive to MEK inhibitors in vitro and in xenograft tumor models (30–32). Arguably, PTCs developing following endogenous expression of BrafV600E in mice represent a more physiological context in which to evaluate this therapeutic approach. We treated animals with the specific allosteric MEK1/2 inhibitor PD325901 for 3 wk beginning at 3 wk of age. Levels of phosphorylated ERK, a downstream target of MEK, were profoundly inhibited 6 h after the last dose (Fig. 4 A and B). Thyroid tumor volume, determined by MRI before and after treatment, was decreased in drug-treated mice (Fig. 4C) and was associated with a modest reduction in the proliferative index of the tumors (Fig. 4D). However, there was no difference in the apoptotic index or in the histopathological appearance of the lesions.

Fig. 4.

Treatment with the Mek inhibitor PD0325901 inhibits Braf-induced PTC growth. LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre mice were treated with PD0325901 (25 mg·kg−1·d−1) or vehicle for 3 wk, beginning at 3 wk of age. (A) Representative H&E sections of thyroids treated with vehicle or PD0325901. (B) pERK IHC of PTCs of vehicle- or PD0325901-treated mice. Animals were euthanized 6 h after administration of the last treatment dose. (C) Thyroid volume measured by MRI in vehicle- or PD0325901-treated mice before and after 3 wk of therapy (P = 0.0002). (D) Proliferative index measured by percentage of Ki67-positive thyrocytes in vehicle- and PD0325901-treated mice. *P = 0.01

Discussion

In this study we show that endogenous expression of BrafV600E in thyroid cells was sufficient to induce PTCs with full penetrance by 3 wk of age. The tumor cells had the typical nuclear features of PTC and were enriched for tall cells, which are characteristic of PTCs with BRAF mutations in humans (9). The evidence for malignancy was supported by their propensity to invade extrathyroidal structures and by the presence of vascular invasion. In humans there is no evidence of a stepwise adenoma–carcinoma transition leading to PTC. Instead, it is likely that a subset of papillary microcarcinomas, which are highly prevalent, represents precursors of the clinically significant forms of the disease. About 25% of micro-PTCs harbor BRAF mutations, which has been taken as evidence that this oncogene may be a tumor-initiating event (9, 33). Previously, PTC was described after high-level overexpression of BRAFV600E in transgenic mice (23). The fact that the disease can be recapitulated by endogenous expression of the oncogene demonstrates convincingly that oncogenic Braf is an initiating event in PTC development and sufficient to drive the process.

The Braf-expressing mice were profoundly hypothyroid due to the shutdown of expression of key genes required for iodine transport and thyroid hormone biosynthesis. This result is consistent with observations in humans, in which PTCs harboring BRAF mutations have lower expression of Tg, TPO, and NIS compared with PTCs that do not have this mutation (34) and accordingly are more refractory to 131I therapy (10). The effects of oncogenic BRAF on thyroid gene expression in vitro takes place within hours (35); however, the LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre mice did not become hypothyroid until 3 or 4 wk after the onset of TPO, and hence Cre, expression, which begins at E14.5. This was most likely due to the fact that thyroid cells do not express TPO in a synchronous fashion, and hence Cre-mediated Braf activation likely took place gradually. In this event, hypothyroidism would ensue only when a sufficient proportion of cells activated the oncoprotein and impaired thyroid hormone biosynthesis, in a way that could no longer be compensated for by the reservoir of unrecombined thyroid cells.

Experiments with immortalized thyroid cell lines have consistently shown that Ras oncogenes inhibit differentiation (27), due in part to interference with Ttf1 activity (36) and decreased expression and transcriptional activity of Pax8 (37). However, a threshold of Ras oncogene expression must be present for these effects to become apparent (28). Our data indicated that endogenous levels of HrasG12V were not sufficient to induce hypothyroidism or to negatively impact thyroid hormonogenesis, which may be due to insufficient MAPK activation (29), which our data strongly implicate in this process (38).

Physiological expression of BrafV600E in lung alveolar epithelial cells and melanocytes of genetically modified mice results in an initial burst of proliferation, followed by growth arrest associated with activation of markers of senescence (17, 18). By contrast, the mitotic rate in Braf-expressing thyroid cells remained high at all times from birth through at least 3 wk of age, which is inconsistent with senescence. It may be that the timing of activation of Braf is a determining factor in transformation. Interestingly, induction of BrafV600E expression during embryogenesis using a tyrosinase-driven Cre results in embryonic lethality and rapid transformation of melanoblasts, suggesting that oncogenic activation at an earlier stage of differentiation is associated with greater malignant potential (39).

The marked elevation of TSH seen postnatally in LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre mice raised the possibility that this hormone may be cooperating with oncogenic Braf in transformation, perhaps accounting for the high penetrance and short latency of the phenotype. However, treatment with TSH-suppressive doses of thyroxine beginning postnatally, at a time when thyroid histology was still normal, did not prevent or dampen the phenotype. This outcome is likely due to the fact that Braf-expressing cells may have become largely refractory to TSH action (35). In addition, as the unliganded TSH receptor retains significant constitutive activity (40), simple absence of ligand may have been insufficient to block the pathway.

Activation of the TSH/TSHR pathway occurs in mice at E15. Although TSH signaling is required for expression of a subset of thyroid-specific genes during development, thyroid gland size and mitotic rate are independent of TSH action prenatally, as previously reported in TshR-KO mice and in mice lacking TSH (i.e., pitdw/pitdw mice, which express a pit1 transcription factor defective in DNA binding) (24). This result is also consistent with our data, in which we found normal mitotic activity in TshR-KO mice at birth. Taken together, this result indicates that deletion of TshR is unlikely to have depleted a putative thyroid progenitor cell population, whose existence has not been definitively established, and whose characteristics have not been fully defined (41). However, TshR-KO cells cannot be viewed as normal, and it is possible that they may have a weaker response to the transforming effects of the oncogene because of an as yet undefined differentiation handicap, such as a block in cell cycle progression that cannot be overcome by constitutive MAPK activation.

The mechanisms accounting for the requirement for TshR for Braf-induced transformation are unknown. There is good evidence that TSH primes thyroid cells to undergo cell cycle progression in response to growth factors, primarily insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) or insulin (2). This effect is associated with increased IRS-2 and PI3K phosphorylation and enhanced MAPK activity (42). TSH also increases insulin, but not IGF-I receptor abundance in human thyroid cells (43). In many of these models exposure to TSH must precede growth factor stimulation for the synergy to fully manifest (2). Our data suggest that this TSH signaling requirement is also important for Braf-induced tumorigenesis. The potential significance of TSH action in the initial events associated with Braf-induced thyroid cell transformation is further supported by the attenuated phenotype seen in mice with thyroid-specific deletion of Gsα. However, the fact that Gsα deletion did not prevent development of PTCs is consistent with the evidence that other TSH-activated downstream pathways, such as Gq/G11, also play a critical role in thyroid cell growth (44).

Although treatment of Braf-induced PTCs with PD0325901 inhibited mitotic activity, the MEK inhibitor did not revert the tumors. It should be noted that although MEK and mTORC1 inhibitors prevented development of melanomas caused by inducible activation of Braf in the context of Pten deletion, they did not induce tumor regression in established tumors (17), which is consistent with our data on Braf-induced murine PTCs. It may be that the effects of PD0325901 on MAPK signaling were not sufficiently profound or sustained to achieve a complete therapeutic benefit.

Several recent large epidemiological studies have shown a strong association between serum TSH levels and risk of malignancy in thyroid nodules (19–21). Remarkably, a fourfold increase in thyroid cancer was found in patients whose TSH levels were in the upper quartile compared with those in the lower quartile of the normal range. Our data suggest that the activity of the TSH signaling pathway may predispose thyroid cells to BRAF-induced transformation, which if confirmed in humans will provide impetus for further delineation of the signaling effectors that mediate this interaction and provide strategies for cancer prevention and therapy.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals.

LSL-BrafV600E mice harbor a latent oncogenic Braf knock-in allele, which following Cre-mediated recombination results in endogenous expression of the oncoprotein (45). TPO-Cre mice express Cre recombinase under the control of the thyroid peroxidase gene promoter, which is active only in thyroid follicular cells beginning at E14.5 (46) (Fig. S1A). FR-HrasG12V mice conditionally express a latent HrasG12V allele under the regulatory control of its endogenous gene promoter (29). TshR-KO mice harbor a germ-line deletion of the TSH receptor (24, 47). The gene encoding Gsα was conditionally deleted by using the Gsα-floxed mouse line Gnas-E1fl/fl, in which loxP recombination sites surround Gsα exon 1 at positions −1601 and +419 relative to the translational start site (48). Mice were in mixed genetic backgrounds. Genotypes were determined by PCR using previously described primers. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry.

Thyroid tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Five-micrometer-thick sections were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or appropriate antibodies described in SI Materials and Methods. Histological diagnosis was performed by a thyroid pathologist (R.G.) blinded to the genotype and the treatment status of the animal. Where indicated, immunohistochemical staining was quantitated using Metamorph imaging software.

Real-Time Reverse Transcription–PCR.

Sequences for β-actin, Tg, NIS, TPO, pax8, ttf1, and TshR are listed in SI Materials and Methods.

Drug Administration.

PD352901 was administered by gavage as detailed in SI Materials and Methods. TSH was suppressed in mice by administration of supraphysiological doses of L-T4 (Sigma).

Thyroid Imaging.

Thyroid imaging was done by high-resolution MR, as detailed in SI Materials and Methods.

Radioimmunoassays (RIA).

Serum TSH and T4 levels were performed as previously described (SI Materials and Methods).

Statistical Analysis.

Mann–Whitney U and Student's t tests were used for statistical analyses of intergroup comparisons. Significance was defined as a P value <0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Miriam Benezra for technical assistance. We thank the following Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center Cores for assistance: Molecular Cytology, Genetically Engineered Mouse Genotyping Service, Laboratory of Comparative Pathology, and Small Animal Imaging. This project was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants CA50706, CA72597, and DK17050; the Margot Rosenberg Pulitzer Foundation; and partially supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. A.F. was supported by NIH Grant F32CA136178. The Small Imaging Core is supported by Small Animal Imaging Research Program Grant R24 CA83084, NIH Center Grant P30 CA08748, and NIH Prostate Specialized Program of Research Excellence Grant P50-CA92629.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1015557108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Tramontano D, Cushing GW, Moses AC, Ingbar SH. Insulin-like growth factor-I stimulates the growth of rat thyroid cells in culture and synergizes the stimulation of DNA synthesis induced by TSH and Graves’-IgG. Endocrinology. 1986;119:940–942. doi: 10.1210/endo-119-2-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimura T, et al. Regulation of thyroid cell proliferation by TSH and other factors: A critical evaluation of in vitro models. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:631–656. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.5.0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roger PP, Servais P, Dumont JE. Stimulation by thyrotropin and cyclic AMP of the proliferation of quiescent canine thyroid cells cultured in a defined medium containing insulin. FEBS Lett. 1983;157:323–329. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parma J, et al. Somatic mutations in the thyrotropin receptor gene cause hyperfunctioning thyroid adenomas. Nature. 1993;365:649–651. doi: 10.1038/365649a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyons J, et al. Two G protein oncogenes in human endocrine tumors. Science. 1990;249:655–659. doi: 10.1126/science.2116665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimura ET, et al. High prevalence of BRAF mutations in thyroid cancer: Genetic evidence for constitutive activation of the RET/PTC-RAS-BRAF signaling pathway in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1454–1457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soares P, et al. BRAF mutations and RET/PTC rearrangements are alternative events in the etiopathogenesis of PTC. Oncogene. 2003;22:4578–4580. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frattini M, et al. Alternative mutations of BRAF, RET and NTRK1 are associated with similar but distinct gene expression patterns in papillary thyroid cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23:7436–7440. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nikiforova MN, et al. BRAF mutations in thyroid tumors are restricted to papillary carcinomas and anaplastic or poorly differentiated carcinomas arising from papillary carcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5399–5404. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xing M, et al. BRAF mutation predicts a poorer clinical prognosis for papillary thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:6373–6379. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elisei R, et al. BRAF(V600E) mutation and outcome of patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma: A 15-year median follow-up study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3943–3949. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies H, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pollock PM, et al. High frequency of BRAF mutations in nevi. Nat Genet. 2003;33:19–20. doi: 10.1038/ng1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brose MS, et al. BRAF and RAS mutations in human lung cancer and melanoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6997–7000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naoki K, Chen TH, Richards WG, Sugarbaker DJ, Meyerson M. Missense mutations of the BRAF gene in human lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7001–7003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhomen N, et al. Oncogenic Braf induces melanocyte senescence and melanoma in mice. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dankort D, et al. Braf(V600E) cooperates with Pten loss to induce metastatic melanoma. Nat Genet. 2009;41:544–552. doi: 10.1038/ng.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dankort D, et al. A new mouse model to explore the initiation, progression, and therapy of BRAFV600E-induced lung tumors. Genes Dev. 2007;21:379–384. doi: 10.1101/gad.1516407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boelaert K, et al. Serum thyrotropin concentration as a novel predictor of malignancy in thyroid nodules investigated by fine-needle aspiration. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4295–4301. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haymart MR, et al. Higher serum thyroid stimulating hormone level in thyroid nodule patients is associated with greater risks of differentiated thyroid cancer and advanced tumor stage. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:809–814. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fiore E, et al. Lower levels of TSH are associated with a lower risk of papillary thyroid cancer in patients with thyroid nodular disease: Thyroid autonomy may play a protective role. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009;16:1251–1260. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jhiang SM, et al. Targeted expression of the ret/PTC1 oncogene induces papillary thyroid carcinomas. Endocrinology. 1996;137:375–378. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.1.8536638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knauf JA, et al. Targeted expression of BRAFV600E in thyroid cells of transgenic mice results in papillary thyroid cancers that undergo dedifferentiation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4238–4245. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Postiglione MP, et al. Role of the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor signaling in development and differentiation of the thyroid gland. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15462–15467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242328999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemoine NR, et al. Activated ras oncogenes in human thyroid cancers. Cancer Res. 1988;48:4459–4463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu Z, Gandhi M, Nikiforova MN, Fischer AH, Nikiforov YE. Molecular profile and clinical-pathologic features of the follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma. An unusually high prevalence of ras mutations. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;120:71–77. doi: 10.1309/ND8D-9LAJ-TRCT-G6QD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Francis-Lang H, et al. Multiple mechanisms of interference between transformation and differentiation in thyroid cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:5793–5800. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.12.5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Vita G, et al. Dose-dependent inhibition of thyroid differentiation by RAS oncogenes. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:76–89. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen X, et al. Endogenous expression of Hras(G12V) induces developmental defects and neoplasms with copy number imbalances of the oncogene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7979–7984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900343106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ball DW, et al. Selective growth inhibition in BRAF mutant thyroid cancer by the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 inhibitor AZD6244. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4712–4718. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu D, Liu Z, Jiang D, Dackiw AP, Xing M. Inhibitory effects of the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibitor CI-1040 on the proliferation and tumor growth of thyroid cancer cells with BRAF or RAS mutations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4686–4695. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leboeuf R, et al. BRAFV600E mutation is associated with preferential sensitivity to mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibition in thyroid cancer cell lines. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2194–2201. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sedliarou I, et al. The BRAFT1796A transversion is a prevalent mutational event in human thyroid microcarcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2004;25:1729–1735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Durante C, et al. BRAF mutations in papillary thyroid carcinomas inhibit genes involved in iodine metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2840–2843. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitsutake N, et al. Conditional BRAFV600E expression induces DNA synthesis, apoptosis, dedifferentiation, and chromosomal instability in thyroid PCCL3 cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2465–2473. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Missero C, Pirro MT, Di Lauro R. Multiple ras downstream pathways mediate functional repression of the homeobox gene product TTF-1. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2783–2793. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.8.2783-2793.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baratta MG, Porreca I, Di Lauro R. Oncogenic ras blocks the cAMP pathway and dedifferentiates thyroid cells via an impairment of pax8 transcriptional activity. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:838–848. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knauf JA, Kuroda H, Basu S, Fagin JA. RET/PTC-induced dedifferentiation of thyroid cells is mediated through Y1062 signaling through SHC-RAS-MAP kinase. Oncogene. 2003;22:4406–4412. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dhomen N, et al. Inducible expression of (V600E) Braf using tyrosinase-driven Cre recombinase results in embryonic lethality. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23:112–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2009.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cetani F, Tonacchera M, Vassart G. Differential effects of NaCl concentration on the constitutive activity of the thyrotropin and the luteinizing hormone/chorionic gonadotropin receptors. FEBS Lett. 1996;378:27–31. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01384-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas D, Friedman S, Lin RY. Thyroid stem cells: Lessons from normal development and thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:51–58. doi: 10.1677/ERC-07-0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ariga M, et al. Signalling pathways of insulin-like growth factor-I that are augmented by cAMP in FRTL-5 cells. Biochem J. 2000;348(Pt 2):409–416. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Keymeulen A, Dumont JE, Roger PP. TSH induces insulin receptors that mediate insulin costimulation of growth in normal human thyroid cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;279:202–207. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kero J, et al. Thyrocyte-specific Gq/G11 deficiency impairs thyroid function and prevents goiter development. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2399–2407. doi: 10.1172/JCI30380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mercer K, et al. Expression of endogenous oncogenic V600EB-raf induces proliferation and developmental defects in mice and transformation of primary fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11493–11500. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kusakabe T, Kawaguchi A, Kawaguchi R, Feigenbaum L, Kimura S. Thyrocyte-specific expression of Cre recombinase in transgenic mice. Genesis. 2004;39:212–216. doi: 10.1002/gene.20043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marians RC, et al. Defining thyrotropin-dependent and -independent steps of thyroid hormone synthesis by using thyrotropin receptor-null mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15776–15781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242322099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sakamoto A, Chen M, Kobayashi T, Kronenberg HM, Weinstein LS. Chondrocyte-specific knockout of the G protein G(s)alpha leads to epiphyseal and growth plate abnormalities and ectopic chondrocyte formation. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:663–671. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.