Abstract

In this study, 342 grade 4-6 elementary school students in Gyeonggi-do were recruited to determine their readiness to change food safety behavior and to compare their food safety knowledge and practices by the stages of change. The subjects were divided into three stages of change; the percentage of stage 1 (precontemplation) was 10.1%, the percentage of stage 2 (contemplation and preparation) was 62.4%, and that of stage 3 (action and maintenance) was 27.5%. Food safety knowledge scores in stage 3 (4.55) or stage 2 (4.50) children were significantly higher than those in stage 1 children (4.17) (P < 0.05). The two food safety behavior items "hand washing practice" and "avoidance of harmful food" were significantly different among the three groups (P < 0.05). Stages of change were significantly and positively correlated with food safety knowledge and practice. Age was significantly and negatively correlated with the total food safety behavior score (r = -0.142, P < 0.05). The most influential factor on the stage of change was a mother's instruction about food safety (P < 0.01).

Keywords: Children, food safety, knowledge, behavior, stages of change

Introduction

The consumer's need for food safety is greatly increasing but the level of food safety education remains stil low. The lack of food safety knowledge results in food safety related health problems [1], and consumers who are undereducated, or have low incomes have limited food safety knowledge and poor food handling practices [2]. Children are most likely to engage in unsafe hand washing practices, as the food safety knowledge level in children is not high enough to protect them [3]. Since Children are particularly vulnerable to food borne illnesses due to their immature immune systems [4], Korea government has tried to decrease the incidence of food poisoning caused by school meals and improve food hygiene behavior.

The development of a food safety education program for children should be tailored to their needs, so they can practice food safety effectively at school or at home. This is most true for children whose mothers work outside the home and who rely on the increased consumption of prepared or unsafe foods [5]. They may also grow into adults without learning the basic principles of safe food preparation [6]. However, few studies have been conducted regarding the food safety behavior and effective food safety education interventions. Therefore, the first step is to identify the level of food safety knowledge and practice in school children and to determine the readiness through stages of change.

In the stages-of-change model, behavioral modification is accomplished through precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance [7]. Education appropriate for the stages of change of the subjects should be performed, rather than a uniform education that does not consider stages for effective behavioral modification [8].

One of the theories actively applied to dietary behavior is the stages of change model [9]. Several studies with Korean population have identified relationships between dietary behavior and stages of change, such as an analysis of sociopsychological factors by the stages of change for fat reducing behavior in adult females [10,11], the development of a behavioral theory-based nutrition education program for women of childbearing age [12], the effect of a follow-up nutrition intervention program applied to the high-risk, undernourished elderly in rural areas [13], a comparison of food and nutrient intake according to the stages of change model for dietary behaviors of elderly females in rural longevity villages [14], and a comparison of vitamin and mineral intake using the stages of change in fruit and vegetable intake in elementary students [15].

However, no study regarding the readiness to change food safety behavior in children has been conducted in Korea. Thus, the purpose of this study was to determine the stages of change in food safety behavior of children and to identify the relationship among the stage of change, food safety knowledge, and practice. We will use these data to develop and implement a food safety education intervention to increase food safety awareness among children.

Subjects and Methods

This survey was conducted with 342 4th-6th grade elementary school students from June 30 to July 31, 2009.

Determining the readiness to change

We modified a questionnaire from previous studies to measure stages of change regarding food safety in children [16, 17]. The stage of change questionnaires focused on three stages: precontemplation (poor problem recognition), contemplation and preparation (some problem recognition, but ambivalence about the need to change), and action (concrete changes in behavior are occurring). Five items that best reflected food safety were used to determine the stages of change in children; "perceptions about food safety", "avoidance of unsafe food", "acceptance of food safety information", "hand-washing practices", and "reading nutrition labels". Subjects were asked to choose one of four statements and were scored; I do not consider it at all (score, -2), I intend to consider it in the near future (score, -1), I am seriously thinking about practicing it within 30 days (score, 1), or I have been practicing it (score, 2). The range of scores was from -10 (close to precontemplation stage) to +10 (close to the action stage). Children were labeled as precontemplative for scores ranging from -10 to -4, (stage 1), contemplative and preparative for a score between-3 and 3, (stage 2), and in an action and maintenance stage for a score between 4 and 10 (stage 3).

Food safety knowledge and practice questionnaire

The survey included the subject's demographic characteristics and general questions about food-safety perception and experience. The five food safety knowledge questions (O/X response) included: proper hand washing, food expiration dates, food storage, food poisoning, and the meaning of Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) guidelines. A correct answer received a score of 1, while a wrong answer received a score of 0. Eight questions were asked to assess food safety practice in children, and the responses were scored on a 5-point Likert scale (5 points = strongly agree, 1 point = strongly disagree). The reliability of the 13 food safety knowledge and practice questions was validated using Cronbach's α (Cronbach's α = 0.84).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the SPSS PC win 12.0 program (SPSS, Inc,, Chicago, IL, USA), after data coding and cleaning. The general subject's characteristics were expressed as either mean with standard deviation for numerical variables or as a frequency and percentage for categorized variables. Significant differences between stages of change and numerical variables were tested by an analysis of variance, and within-group differences were identified by Duncan's post-hoc test. Variables with categorized scores were analyzed using the χ2-test. A regression analysis was conducted to identify variables associated with the stages of change; the dependent variable was the stage of change and the independent variables included gender, age, eating habits, food-safety related concerns, knowledge, and practice scores.

Results

General characteristics of the subjects

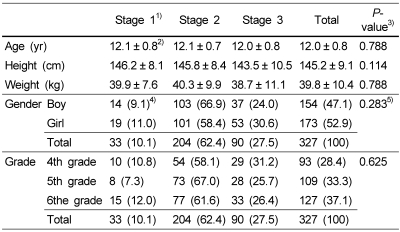

The mean age of the subjects was 12.0 years with a mean height of 145.2 cm and a mean weight of 39.8 kg (Table 1). Among all subjects, 47.1% were boys, and 52.9% were girls. Fourth graders comprised 28.4% of the subjects, fifth graders 33.3%, and sixth graders 37.1%. When the stage of change for food safety behavior was divided into three stages, two-thirds of the subjects (62.4%) were at stage 2 (preparation stage), and the remaining subjects were either at stage 1 (precompletation stage) (10.1%) or stage 3 (action) (27.5%). No significant differences were found between the stages of change and gender, grade, or any of the physical characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the subjects

1)Stage 1: seldom thinks about food safety

Stage 2: thinks that food safety is important and has the intent to practice but does not practice

Stage 3: actively looking for methods to practice food safety and continuously practicing

2)Mean ± SD

3)P-value by ANOVA

4)Number of subjects (percentage)

5)P-value by χ2-test

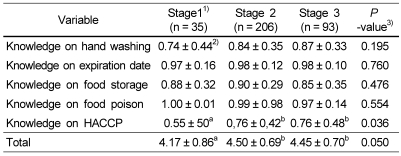

Food safety knowledge and the stages of change

Among the five food safety knowledge questions, the question about the meaning of HACCP had the lowest score of correct answers, and two questions about hand washing and the meaning of the expiration date had excellent scores (Table 2). Only one question about HACCP showed significant differences among the three groups; children at stage 3 had a better knowledge score (0.76) than children at stage 1 (0.55) (P < 0.05). The total knowledge score in children at stage 3 (4.45/5.00) or stage 2 (4.50/5.00) was significantly higher compared to the score for children at stage 1 (4.17/5.00) (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Food safety knowledge by stages of change in children

1)See the Table 1.

2)Mean ± SD

3)P-value by ANOVA

a,bNumbers with different letter superscripts in the same row are significantly different (Duncan's test, P = 0.05).

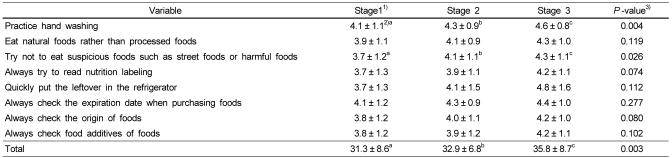

Food safety practice and the stages of change

Eight food safety practice questions were asked (Table 3). Children had the highest score for the question about hand washing practice prior to eating; they scored 4.42/5.00, whereas the question about food handling practices at home showed the lowest score of 3.98/5.00. The scores for hand washing practice prior to eating were 4.1 (stage 1), 4.3 (stage 2), and 4.6 (stage 3) (P < 0.01). The scores for the behavior not to eat harmful food were 3.7 for stage 1, 4.1 for stage 2, and 4.3 for stage 3 (P < 0.05). In total, food safety behavior scores of the stage 1 group (31.3) were significantly lower than those for stage 2 (32.9) or stage 3 (35.8) (P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Food safety practice and the stages of change in children

1)See the Table 1.

2)Mean ± SD

3)P-value by ANOVA

a,bNumbers with different letter superscripts in the same row are significantly different (Duncan's test).

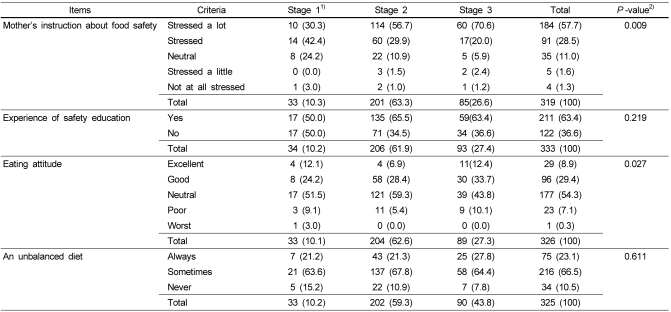

Factors associated with stage of change in food safety behavior

In total, 63.4% of children answered that they had food safety education experience, but that experience was not related significantly with the stages of change (Table 4). More than half of the children (57.7%) answered that their mothers stressed about food safety at home. The mother's food safety instruction at home was significantly associated with the stage of change (P < 0.01); 30.3% of stage 1 children answered that their mother stressed food safety at home, when compared with 56.7% of stage 2 and 70.6% of stage 3 children. More subjects at stage 3 (33.7%) answered that they had good eating attitudes at the table than subjects at stage 1 (28.4%) or stage 2 (24.2%) (P < 0.05).

Table 4.

Association of some factors with stages of change in children N (%)

1)See the Table 1

2)P-value by by χ2-test

Influences of educational experience, grade, and the stages of change on knowledge and behavior

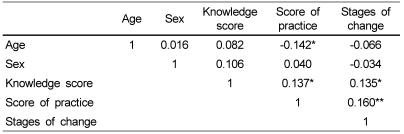

Stages of changes were correlated significantly with food safety knowledge (P < 0.05) and food safety practice (P <0.01) (Table 5). Food safety practice was significantly and positively correlated with food safety knowledge (P < 0.05). Age was negatively correlated with food safety practice scores (P < 0.05).

Table 5.

Correlations between stages of change and food safety behavior

*P < 0.05

**P < 0.01

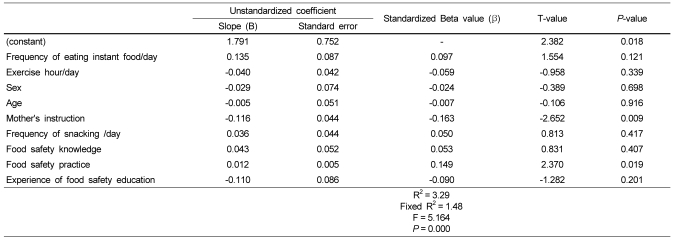

The most influential factors on the stages of change are shown in Table 6. The explanation of these factors accounted for 30% (R2 = 3.29) P < 0.01). The two important factors that influenced the stage of change were the degree of mother's instruction about food safety at home (P < 0.01) and the total food safety behavior score (P < 0.05). No significant effects of age, sex, or food safety knowledge of the subjects on the stage of changes were found.

Table 6.

A regression analysis of the effects of various factors on the stage of change

aDependent variable: stages of behavior change

Discussion

In this study, children were divided into three stages of precontemplation (stage1), contemplation and preparation (stage 2), and action and maintenance (stage 3), rather than five stages of change: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance [18]. Previous studies have shown that the number of subjects in the contemplation stage is small; thus, contemplation was combined with preparation and action was combined with maintenance, which showed the same results as when using five stages of change [14].

Two-thirds of children (62.4%) were in the preparation stage of change (Table 1), indicating that they think food safety is important and that they will practice it in the near future. These results are quite encouraging and this is most clearly reflected by the observation that almost two-thirds (63%) of children in our study reported receiving food safety education in school (Table 4).

Because no other study regarding stages of change and food safety behavior in children has been conducted, we cannot confirm whether this percentage of stages of change in food safety behavior is appropriate. A study concerning vegetable intake and the stages of change in children in Chungnam area, Korea, showed that 31.6% of the subjects were in the precontemplation stage, 33.2% in the contemplation and preparation stage, and 33.2% in the action stage. A study by Byrd-Bredbenner et al. [16] reported that most young adults (mean age, 19-years) remained between the contemplation and preparation stage (stage 2) regarding the preparation of safe food.

We have shown that stages of change were significantly correlated with both food safety knowledge (P < 0.05, Table 2) and food safety practice (P < 0.01, Table 3). The total knowledge and practice scores were relatively low in the precontemplation and contemplation/preparation stages, compared to the action/maintenance score, which supports the validity of the stage model for food safety behavior. A study with young adults showed that participants in the maintenance stage of change significantly outperform all other stages on food safety knowledge scores, and that the stages of change have many significant effects on behavior and psychosocial and knowledge measures [16]. A significant and positive correlation between food safety knowledge and behavior has also been reported [19,20].

Age was negatively correlated with food safety practices (Table 5), possibly due to the difference in the readiness of education acceptance by age. Younger children are more accepting and obedient of parent and teachers education, whereas older children and adolescents tend to be more ignorant of these instructions and try to be more independent. Therefore, it should be stressed that food safety knowledge is not accumulated voluntarily as children get older unless they are taught; thus, an effective step-by-step food safety education program at elementary schools is necessary.

The most important influential factor for the readiness to change was the degree of mother's food safety instruction at home (Table 6). Some studies have shown that a significant proportion of food borne illnesses arise from practices in the home kitchen and that the role of mothers is extremely important for their children's food safety practice [21-24]. The current status quo in Korea shows a rise in the number of full-time working mothers [25], which may become a problem, as children receive most of their food safety education from their mothers. This could be solved by strengthening the school food safety education program; thus, replacing the roles of the mothers to that of teachers to instruct children about food safety.

The limitations of this study are that the sample was restricted to children enrolled in the same local elementary school, and it was cross-sectional in design, so we cannot clarify whether stages of change were the cause or result of a high food safety knowledge and practices score. Furthermore, we used five statements instead of the commonly used single statements [16] or 12 statements [8,17] to determine stages of change for the following reasons; First, food safety cannot be defined in a single statement, such as "I have never thought about food safety in my diet" (contemplation) or "I am practicing food safety in my diet" (action). So, we included four additional items that are significantly related to food safety in the diet, such as hand washing, eating harmful (strange) foods, reading nutrition labels, and accepting food safety information. Second, based on the results of a pre-test with children that used a single question and 12 questions, 12 questions were too long and too ambiguous for children to answer and a single question was resulted in mindless answers. More studies regarding the readiness to change food safety and efficient scoring algorism to determine the stage of change are needed to apply the stages of change model more effectively. In conclusion, most of the subjects in this study already recognized food safety as an important matter in their diets and for health, and they were ready to accept food safety education. Strategies and education increasing self efficacy about food safety and focused on the contemplation and preparation stage, such as teaching the proper way of hand washing may help students move to the next stage of change.

References

- 1.Sammarco ML, Ripabelli G, Grasso GM. Consumer attitude and awareness towards food-related hygienic hazards. Journal of Food Safety. 1997;17:215–221. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altekruse SF, Street DA, Fein SB, Levy AS. Consumer knowledge of food borne microbial hazards and food-handling practices. Journal of Food Protection. 1996;59:287–294. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-59.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim MR, Jeon MK, Kim HC. Analysis of the Effects of an Educational Program regarding Food Safety for Children. Journal of the Korean Home Economics Association. 2006;44:113–120. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheule B. Food safety education: Health professionals' knowledge and assessment of WIC client needs. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2004;104:799–803. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacPherson C, Haggans C, Reicks M. Interactive homework lessons for elementary students and parents: A pilot study of nutrition expedition. Journal of Nutrition Education. 2000;32:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williamson DM, Gravani RB, Lawless HT. Correlating food safety knowledge with home food preparation practices. Food Technology. 1992;46:94–100. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Block G, Wakimoto P, Metz D, Fujii ML, Feldman N, Mandel R, Sutherland B. A randomized trial of the little by little CD-ROM: demonstrated effectiveness in increasing fruit and vegetable intake in a low-income population. Prev Chronic Dis. 2004;1:A08. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kristal AR, Glanz K, Curry SJ, Patterson RE. How can stages of change be best used in dietary interventions? J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:679–684. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oh SY, Cho MR, Kim Rim JO. Analysis on the Stages of Change in Fat Reducing Behavior and Social Psychological Correlates in adult Female. Korean Journal of Community Nutrition. 2000;5:615–623. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung EJ. Comparison of nutrient intakes regarding Stages of Change in Dietary Fat Reduction for College Students in Gyeonggi-do. Journal of the Korean Society of Food Science and Nutrition. 2004;33:1327–1336. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oh SY, Kim KA, You HE, Chung HR. Development of a theory based nutrition education program for childbearing aged women in Korea. Korean Journal of Community Nutrition. 2004;9:725–733. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park MY, Chun BY, Joo SJ, Jeong GB, Huh CH, Kim GR, Park PS. A Comparison of Food and Nutrient Intake Status of Aged Females in a rural long life community by the stage model of dietary behavior change. Korean Journal of Community Nutrition. 2008;13:34–45. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park PS, Chun BY, Jeong GB, Huh CH, Joo SJ, Park MY. The effect of follow-up nutrition intervention programs applied aged group of high risk undernutrition in rural area (I) Korean Journal of Food Culture. 2007;22:127–139. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suh Y, Chung Y. Comparison of mineral and vitamin intakes according to the stage of change in fruit and vegetable intake for elementary school students in chungnam province. The Korean Journal of Nutrition. 2008;41:658–666. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byrd-Bredbenner C, Maurer J, Wheatley V, Schaffner D, Bruhn C, Blalock L. Food safety self-reported behaviors and cognitions of young adults: results of a national study. J Food Prot. 2007;70:1917–1926. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-70.8.1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rollnick S, Heather N, Gold R, Hall W. Development of a short "readiness to change" questionnaire for use in brief, opportunistic interventions among excessive drinkers. Br J Addict. 1992;87:743–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psychol. 1992;47:1102–1114. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim MR, Kim HC. Evaluation of knowledge and behaviors towards food safety and hygiene of children. Korean Journal of Human Ecology. 2004;14:871–881. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoon HJ, Yoon KS. Elementary school students' knowledge, behavior and request for education method associated with food safety. Journal of the Korean Dietetic Association. 2007;13:169–182. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bryan F. Risks of practices, procedures and processes that lead to outbreak of foodborne diseases. Journal of Food Protection. 1988;8:663–667. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-51.8.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott E. A review: Foodborne disease and other hygienic issues in the home. J Appl Bacteriol. 1996;80:5–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1996.tb03181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medeiros LC, Hillers VN, Chen G, Bergmann V, Kendall P, Schroeder M. Design and development of food safety knowledge and attitude scales for consumer food safety education. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:1671–1677. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sudershan RV, Subba Rao GM, Pratima Rao M. Food safety related perceptions and practices of mothers-A case study in Hyderabad, India. Food Control. 2008;19:506–513. [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Statistical Office. Annual Report on the Economically Active Population Survey. Korea: 2009. p. 48. [Google Scholar]