To the Editor,

Acute necrotizing esophagitis (ANE) or “black esophagus” is defined as a circumferential dark pigmentation of the esophagus on endoscopy and mucosal necrosis on histology [1, 2]. Due to its rarity, the etiopathogenesis of this alarming finding is poorly understood [3, 4]. We report a case of ANE in an alcoholic with achalasia and discuss the pathophysiologic insights gained from this unusual presentation.

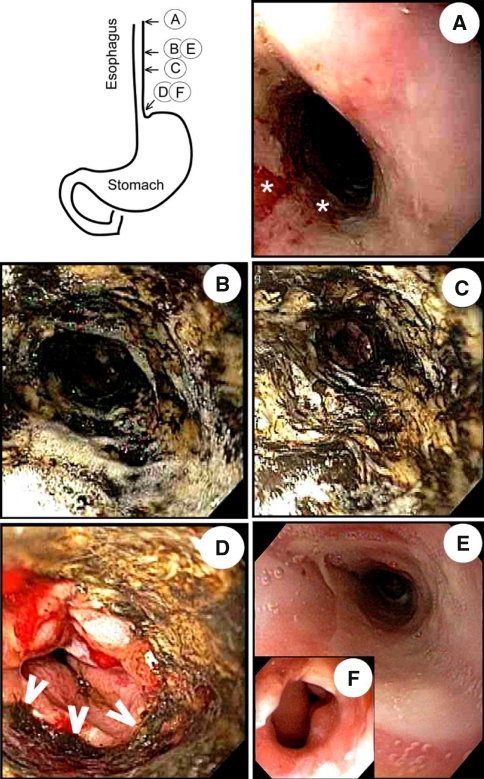

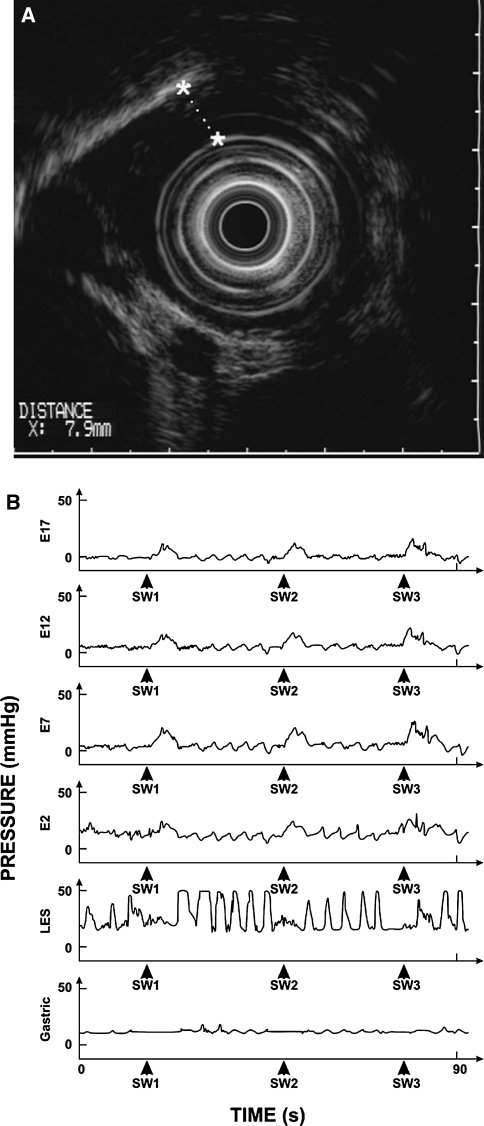

A 56-year-old man with a long-standing history of dysphagia to liquids greater than solids presented with a 2-day history of worsening dysphagia, odynophagia, retrosternal chest pain, and hematemesis. Past medical history was significant for chronic hepatitis C infection and excessive alcohol consumption (vodka) often associated with ‘passing out’. On exam, he was afebrile, tachycardic, orthostatic, and had dry mucus membranes. Laboratory tests were significant for leukocytosis, mild anemia, and pre-renal azotemia. Esophago-gastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed a well-demarcated, circumferential greenish-black discoloration of the mucosa lining the distal half of the esophagus, ending 1–2 cm proximal to the squamo-columnar junction (Fig. 1a–d). Brush cytologies from the black segment and superficial biopsies from the edges showed reactive glandular cells with acute inflammation and necrosis, but no evidence of viral or fungal infections. Clinical diagnosis of ANE was made and supportive therapy with intravenous proton pump inhibitor (PPI), broad-spectrum antibiotics, and aggressive fluid resuscitation were initiated. Symptoms improved within the next 72 h and the patient was discharged on oral PPI therapy with a recommendation to enroll into an alcohol de-addiction program. After 6 weeks of abstaining from alcohol, follow-up EGD revealed that the black discoloration had completely resolved and was replaced by normal-colored mucosa with mild scarring (Fig. 1e). Despite the resolution of acute symptoms, dysphagia persisted and progressively worsened within the next 2 months, which warranted further investigations. Repeat EGD revealed a mid-esophageal stricture (Fig. 1f) and an endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and CT scan confirmed the presence of an unusually thickened muscularis propria in the thoracic esophagus (Fig. 2a). Given the thickened esophagus and long-standing dysphagia, an underlying motility disorder was suspected. Esophageal manometry revealed a complete absence of peristalsis along the entire length of esophagus, increased LES tone and absence of swallow-induced LES relaxation, consistent with achalasia (Fig. 2b). Calcium channel blocker therapy was initiated and the patient was referred for surgical myotomy. Unfortunately, he expired 2 months later due to relapsed heavy alcoholism and related complications.

Fig. 1.

Black esophagus: Images of the esophagus acquired during upper endoscopy show linear ulceration (asterisk) of the mucosa lining the proximal half of the esophagus (a), and circumferential greenish-black appearance in the distal half of the esophagus (b, c). This segment of black discoloration ended abruptly 1–2 cm proximal to the squamo-columnar junction (d, arrowheads); appearance consistent with a diagnosis of acute necrotizing esophagitis (ANE). Image acquired during a follow-up endoscopy shows complete replacement of the black segment with normal mucosa within 6 weeks (e), and development of distal esophageal strictures within 4 months (f). (Color figure online)

Fig. 2.

Achalasia Cardia. a Endoscopic ultrasound showed wall thickening of the thoracic esophagus, primarily involving the muscularis propia with a maximal thickness of ~8 mm (stars with interrupted line). b Esophageal manometry record shows three swallow-induced events (SW1, SW2, and SW3) in the esophagus, LES (lower esophageal sphincter), and stomach. Note that each swallow is associated with a simultaneous pressure wave in the esophagus and there is no LES relaxation, findings consistent with a diagnosis of achalasia esophagus

ANE has been associated with caustic/chemical injury [1], ischemia [1], viral infection [5], gastric outlet obstruction [1], gastric volvulus [6], and antibiotic hypersensitivity [7]. Among chemicals, alcohol can also cause ANE by inducing lactic acidosis and low systemic perfusion [8]. Besides this metabolic and circulatory effect, alcohol can also induce erosive esophagitis [9] by directly affecting the mucosal integrity [10]. We propose that in our patient achalasia and alcoholism were not just co-existing conditions with ANE, but played a key pathophysiologic role as predisposing factors. Alcohol-induced chemical esophagitis is the likely cause of ANE in our patient and the underlying achalasia could have exacerbated the effects of alcohol-induced esophagitis by prolonging the mucosal contact time with ethanol. Given that patients with achalasia rely heavily on gravity to clear the aperistaltic esophagus of its contents, and our patient reported regularly passing out after excessive drinking, i.e., eliminated gravitational clearing of the esophagus by assuming supine posture, the risk of stasis-esophagitis was likely heightened. In keeping with the reported high mortality of 31.8–34.5% [2, 3], our patient also did not fare well, and died within 6 months due to stricture-related complications. Taken together, this case provides a unique pathophysiologic insight into how Achalasia and ANE, two distinct diseases of the esophagus, may be linked.

Acknowledgments

Financial conflicts

None to declare.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Goldenberg SP, Wain SL, Marignani P. Acute necrotizing esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1990;25:534–538. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90844-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gurvitis GE, Shapsis A, Lau N. Acute esophageal necrosis: a rare syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:29–38. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1974-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Augusto F, Fernandes V, Cremers MI. Acute necrotizing esophagitis: a large retrospective case series. Endoscopy. 2004;36:411–415. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geller A, Aguilar H, Burgart L, et al. The black esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:2210–2212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cattan P, Cuillerier E, Cellier C, et al. Black esophagus associated with herpes esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;43:105–107. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(99)70455-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kram M, Gorenstein L, Eisen D, et al. Acute esophageal necrosis associated with gastric volvulus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:610–612. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(00)70304-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mangan TF, Thompson CA, Wytock DH. Antibiotic-associated acute necrotizing esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:900. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90997-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Endo T, Sakamoto J, Sato K, et al. Acute esophageal necrosis caused by alcohol abuse. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;21(11):5568–5570. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i35.5568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akiyama T, Inamori M, Lida H, et al. Alcohol consumption is associated with an increased risk of erosive esophagitis and Barrett’s epithelium. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;11:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-8-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bor S, Bor-Caymaz C, Tobey NA, et al. Esophageal exposure to ethanol increases risk of acid damage in rabbit esophagus. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:290–300. doi: 10.1023/A:1026646215879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]