Abstract

Objective

To investigate the feasibility, reliability, and validity of comprehensively assessing physician-level performance in ambulatory practice.

Data Sources/Study Setting

Ambulatory-based general internists in 13 states participated in the assessment.

Study Design

We assessed physician-level performance, adjusted for patient factors, on 46 individual measures, an overall composite measure, and composite measures for chronic, acute, and preventive care. Between- versus within-physician variation was quantified by intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC). External validity was assessed by correlating performance on a certification exam.

Data Collection/Extraction Methods

Medical records for 236 physicians were audited for seven chronic and four acute care conditions, and six age- and gender-appropriate preventive services.

Principal Findings

Performance on the individual and composite measures varied substantially within (range 5–86 percent compliance on 46 measures) and between physicians (ICC range 0.12–0.88). Reliabilities for the composite measures were robust: 0.88 for chronic care and 0.87 for preventive services. Higher certification exam scores were associated with better performance on the overall (r = 0.19; p <.01), chronic care (r = 0.14, p = .04), and preventive services composites (r = 0.17, p = .01).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that reliable and valid comprehensive assessment of the quality of chronic and preventive care can be achieved by creating composite measures and by sampling feasible numbers of patients for each condition.

Keywords: Comprehensive assessment, quality of care, primary care, composite measures

BACKGROUND

Several recent national research reports point to significant gaps and variability in the quality of care patients receive in the U.S. health care system (Institute of Medicine 2001; McGlynn et al. 2003; Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research [AHRQ] 2005; Nelson et al. 2007;). It is not clear whether and to what extent these gaps are concentrated among subgroups of physicians or reflect widespread variability in physician-level quality. Our current understanding of physician-level quality is limited to performance on only one or a few conditions, and investigators have raised concerns about the ability to differentiate performance among physicians using current process and outcome measures (Hofer et al. 1999; Landon et al. 2003; Holmboe et al. 2006; Campbell et al. 2007; Young et al. 2007; Bodenheimer 2008; Landon and Normand 2008; Kaplan et al. 2009;). Other methodological concerns include insufficient and inadequate quality measures, inadequate adjustments for patient factors, clustering of performance at the physician level requiring larger patient and physician sample sizes for adequate statistical power, difficulty in determining appropriate standards (thresholds) at the physician level, and lack of uniformity of data collection and audits (Landon et al. 2003; Lee 2007; Bodenheimer 2008; Landon and Normand 2008; Kaplan et al. 2009;).

For example, pay for performance (P4P) is one increasingly popular approach to measure and reward individual physicians (Campbell et al. 2007; Lee 2007; Young et al. 2007;). P4P programs generally target only one or a limited set of conditions and performance measures. For example, the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services' (CMS) Physician Quality Reporting Initiative only requires reporting on three measures (CMS 2008), and the current criteria for qualification as a patient-centered medical home focus solely on practice-level structural and some process characteristics (National Committee for Quality Assurance [NCQA] 2010).

Against this backdrop, there is intense interest in new models of primary care, such as the patient-centered medical home. The medical home practice model is designed to provide patient-centered, longitudinal, coordinated, and perhaps most important, comprehensive care to meet the needs of its patients (Hofer et al. 1999; American College of Physician [ACP] 2007;). There is thus a pressing need for creating more robust performance measurement methods to effectively evaluate the comprehensive nature of this practice model (Palmer et al. 1996; ACP 2007;). One study attempted to benchmark physicians using administrative claims data from nine health plans on 10 quality measures. The authors found the majority of physicians did not have a sufficient number of “quality events” for reliable assessment of physician quality at the individual measure level, and only 15–20 percent of physicians had enough events for a reliable overall composite measure (Scholle et al. 2008). In a more recent study of a multipayer primary collaborative within a single multispecialty group, sufficient reliability at the individual physician level could only be found for preventive care measures (Sequist et al. 2010). These studies highlight the difficulty in assessing physician's performance in practice comprehensively across preventive and chronic care, but to our knowledge few if any studies have attempted to assess multiple conditions across chronic, acute, and preventive care using multiple measures per condition with existing, well-tested quality measures that will be needed to effectively evaluate a practice as a patient-centered medical home.

General internal medicine (GIM) practice is a logical setting for such performance assessment because many of the currently endorsed measures are applicable to general internists, and GIM practice is a major focus of the medical home practice model. Our primary objectives in this study were to (1) investigate the feasibility of comprehensively assessing the practice performance of general internists using existing, widely endorsed performance measures and (2) assess the reliability and validity of composite measures across chronic, acute, and preventive care composite measures. Our secondary objectives were to (1) examine the associations of physician-level performance on chronic, acute, and preventive care measures within the same physician's practice using composite measures and (2) compare the variation in performance between and within physicians.

METHODS

Physician Sample

From a pool of interested volunteer participants (N = 534), we recruited 254 general internists with time-limited board certification due to expire between 2007 and 2009 who agreed to undergo a comprehensive assessment of their practice through medical record audit and a self-report of their systems capability (Holmboe et al. 2010). The participants were drawn from 13 states sorted by the 2005 AHRQ quality ranking of medical care within groups (AHRQ 2005) so as to draw physicians from the United States with variable levels of practice size and performance.

Participants received a U.S.$1,000 incentive; U.S.$500 at the time of enrollment, and U.S.$500 when they completed the entire project. The project was approved by the New England Institutional Review Board, and all physicians were consented for participation. It is a convenience sample of diverse, volunteer general internists in ambulatory practice settings to test comprehensive assessment methods.

Patient Sample

The eligibility criteria for patients were age between 18 and 90 years, participating physician was their primary provider, and the patient had been seen at least once by the physician between July 1, 2005 and June 30, 2006. The audit collected information on patient demographics (age, ethnicity, gender) and comorbidity using the Charlson comorbidity index (Charlson et al. 1994).

The practice was instructed to identify patients where the physician subject was designated as the primary provider with these specific conditions (using ICD-9 codes): 20 patients with diabetes, hypertension (without diabetes), heart disease (any combination of coronary artery disease, acute myocardial infarction, and/or congestive heart failure), osteoarthritis (knee or hip), acute infection (any combination of upper respiratory or urinary tract infection), and 10 patients with acute low back pain for a target total sample of 110 medical records. The index date for the study was June 30, 2006 and practices were instructed to use a retrospective sequential sampling strategy to identify the target groups of patients until they reached the required sample size per condition or reached July 1, 2005. Regardless of the primary indication for sampling, all applicable chronic and acute care measures, and preventive services measures were audited for each patient.

Data Collection

The medical record audit was performed by trained abstractors (Westat Inc., Rockville, MD). Westat field managers received training from ABIM staff on the use of a web-based data collection tool, the Comprehensive Care Practice Improvement Module and use of a comprehensive abstraction manual covering detailed specifications for all performance measures, including detailed specifications for measures such as functional status, and eligible disease conditions. Field managers then trained abstractors using these materials and three training medical records. Abstractor performance was then assessed on agreement for 109 data elements used to calculate the 46 performance measures using six reference patient charts scored previously by ABIM physician experts following abstraction specifications. Abstractors had to obtain an average agreement per reference chart of at least 85 percent in six domains before they could begin actual chart abstractions in practices (range of abstractor reliabilities per training chart were 0.43–0.96 using a kappa-based estimate). ABIM and Westat coordinators reviewed a 5 percent sample of the abstractors' audits from the physician offices for quality control purposes during field operations, and physician subjects were also instructed to inform the ABIM of any perceived irregularities or problems. One abstractor was subsequently removed after completing one office due to poor reliability and the physician's medical records were reaudited.

Description of Measures

The audit targeted seven chronic conditions: diabetes, coronary artery disease, postacute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and osteoarthritis; four acute care conditions: upper respiratory infection, urinary tract infection, low back pain, and acute depression; and six preventive services: smoking cessation counseling, influenza and pneumococcal immunizations, and mammography, colorectal cancer, and osteoporosis screening. These measures were selected using a consensus process by a panel of experts in quality measurement and improvement, basing their decision on the high prevalence and health impact of the conditions in the U.S. population, commonly cared for by general internists and for which validated measures were available.

We used National Quality Forum (NQF) endorsed measures for all the chronic care and preventive services measures (NQF 2008); the acute care measures were derived from the RAND Corporation's Quality Assessment Tools (Kerr et al. 2000). In all, 46 performance measures (Appendix SA2) were abstracted for this study. Scoring for all measures was dichotomous, based on whether the patient had achieved a threshold value for outcome measures (e.g., hemoglobin A1c <7.0 percent) or the process of care had been performed.

To summarize physician performance we calculated two types of composite performance scores—one for each specific disease condition (e.g., diabetes, osteoarthritis) and a more comprehensive composite created by aggregating conditions by care type (i.e., acute care, chronic care, and preventive services) for each physician. For each individual measure, a physician-level unadjusted score was computed as the percentage of patients who “met” the goal. The individual measures were also adjusted for patient factors, including age, race, ethnicity, and comorbidity (Charlson et al. 1994), using a random physician-intercept logistic model. We first calculated the expected logit values of individual measures using the random physician intercept term (shrinkage estimator) and estimated coefficients of the covariates from the risk-adjusted model and means of patient risk factors of the entire patient sample. Then we transformed the expected logit value onto the probability scale and used this to represent the adjusted score (Hasnain-Wynia et al. 2007). The composite measure score of a disease (e.g., diabetes) or a general care type (e.g., chronic care) was computed using the indicator average method (Reeves et al. 2007). For example, for each physician the composite score for preventive services was computed by averaging the percentages of its six individual measures (i.e., smoking cessation counseling, influenza immunizations, pneumococcal immunizations, mammography, colorectal cancer screening, and osteoporosis screening) giving each measure equal weight. We chose to use indicator average method because we intended to assess quality with respect to the processes of care and to avoid potential overrepresentation of frequently triggered individual measures.

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics of the 254 physicians who began the study and the 236 physicians who completed the chart audit were reviewed. Descriptive statistics, including means, standard errors, and ranges, were computed at patient and physician levels for each individual performance measure. For eligible patients, a process measure was scored as “not meeting goal” if it was not recorded on chart audit, and an outcome measure was scored as “not meeting goal” if the test had been performed within the index period but did not meet the goal, was not recorded on chart audit, or was out of date. If a test had a result out of plausible range but with a valid date, then the outcome measure was set as missing. The missing data rates for outcome measures ranged from 0.5 to 2 percent.

To quantify reliability of the performance estimates, we estimated intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for each performance measure. The ICC is the ratio of variation between physicians' practice means (σp2) to the total measure variation where the latter is defined as the sum of the within- (σe2) and between-practice variation (ICC=(σp2)/(σp2+σe2)). An ICC close to one implies a reliable physician “thumbprint” in that the between-physician variation is relatively larger than the within-physician variation; measures having physician-level reliability >0.85 can be considered sufficiently reliable for comparing physicians scoring over or under a threshold value (Kaplan et al. 2009). We estimated the ICC using a multilevel random effect logistic model (NLMIXED procedure, SAS version 9.1.3). Ninety-five percent confidence intervals were calculated using the delta method (Reeves et al. 2007). We reestimated the random effects logistic model adjusting for patient factors, including age, comorbidity index, ethnicity, and gender, to obtain adjusted ICC estimates. Box plots of the performance scores and Pearson correlations across the risk-adjusted performance scores were computed. Composite score reliabilities were estimated by combining ICC estimates and variances from the component performance scores (Feldt and Brennan 1989). To assess external validity, we calculated Pearson correlation coefficients for the association among the composite scores and physician characteristics that included location of medical school training, initial Internal Medicine Board Certification scores, and number of attempts needed to pass the certification examination.

Finally, we estimated the patient sample size per measure needed to achieve a high level of reliability (i.e., 0.85) and compared this number to the actual sample sizes. When the number of needed patients was less than or equal to the actual physician panel size, then the sample size was deemed adequate. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1.3.

RESULTS

Physician Characteristics

The mean age of the 236 physicians was 42 (range 33–69), 36 percent were female, and 37 percent were in solo practice, 28 percent in single specialty medical group or partnership, 23 percent in multispecialty group or partnership, and 7 percent in academic faculty practice (Table 1). This was consistent with our goal of sampling a diverse set of GIM practice in the United States.

Table 1.

Overview of Physician Characteristics

| Characteristics | 254 Volunteers | 236 Completers |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean [SD], range) | 42 (6.2), 33–69 | 42 (6.2), 33–69 |

| Female | 35% | 36% |

| State distribution (%) | ||

| CA | 21 | 19 |

| NY | 14 | 14 |

| FL | 7 | 8 |

| TX | 10 | 11 |

| NJ | 11 | 11 |

| IL | 7 | 7 |

| OH | 8 | 9 |

| MA | 6 | 5 |

| MD | 5 | 6 |

| TN | 4 | 4 |

| MO | 3 | 3 |

| CO | 2 | 1 |

| NV | 2 | 2 |

| Practice types (%)* | ||

| Solo physician medical practice | 36 | 37 |

| Single specialty medical group or partnership | 28 | 28 |

| Multispecialty group or partnership | 22 | 23 |

| Community health center | 1 | 1 |

| Residency teaching clinic | 1 | 0 |

| Hospital department group practice | 3 | 2 |

| Academic faculty practice | 7 | 7 |

| Other | 2 | 1 |

Complete practice type data available for 244 out of 254 (96%), and 227 out of 236 (96%), respectively.

Patient Characteristics

Key patient characteristics, clustered at the physician level, showed substantial variability between physicians (Table 2). For example, the mean patient age ranged from 44 to 77 years, and the proportion of males ranged from 10 to 75 percent. The mean Charlson comorbidity score and other factors that can affect delivery of patient care also varied substantially between physicians (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean Patient Characteristics Measured at the Physician Level (Chart Review of 22,526 Patients among 236 Physicians)

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | Range across Physicians |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60 (6.0) | 44–77 |

| Patients with age ≥65 | 44% (0.16) | 5–89% |

| Male gender | 40% (0.12) | 10–75% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 37% (0.32) | 0–99% |

| Non-Hispanic black | 9% (0.18) | 0–100% |

| Hispanic | 8% (0.18) | 0–100% |

| Unknown race | 46% (0.37) | 0–100% |

| Drug/alcohol abuse | 2% (0.02) | 0–13% |

| Psychiatric/cognitive impairment | 15% (0.15) | 0–60% |

| Problems with adherence to treatment | 5% (0.08) | 0–52% |

| Social factors limiting self-care | 13% (0.18) | 0–100% |

| Comorbidity index | 1.0 (0.55) | 0.02–3.5 |

| Patients with comorbidity index > 2 | 11% (0.09) | 0–48% |

Performance Results

Overall, the mean number of medical record audits completed per physician was 95 (goal was 110 charts per physician; 86 percent of overall target). Only 72 physicians (31 percent) were able to identify the prespecified numbers for all the targeted conditions combined in the 1-year study frame. However, 193 physicians (82 percent) did meet the sampling targets for four conditions, and over 90 percent of physicians achieved the target sample for hypertension and diabetes.

Physicians performed better on the chronic care process measures that involved a laboratory test or medication than measures involving medical history or examination (Table 3). For example, performance on completion of a foot exam with monofilament (10 percent), documented eye examination (19 percent) for diabetics, and level of pain assessment for osteoarthritis (16 percent) were all substantially low. Performance on the acute care measures was substantially more variable compared with the chronic care measures. For example, while physicians appropriately avoided the use of inappropriate drugs like antidepressants in acute low back pain (86 percent), the quality of documentation for key aspects of the history was poor. Finally, none of the performance rates for the preventive services measures were >62 percent.

Table 3.

Physician Performance on Chronic and Acute Conditions and Prevention

| Item | Physician and Cluster Size | Adjusted for Patient Risks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICC | ||||||

| Description | K | n0* | Physician Level Mean (SD) | ρ | 95% CI | N for Rm=0.85† |

| Chronic medical conditions diagnosed | ||||||

| Lipid control (CAD and DM) | ||||||

| CHD, DM: complete annual lipid test | 236 | 39.3 | 0.74 (0.14) | 0.19 | 0.15–0.23 | 23.9 |

| CHD, DM: LDL<130 mg/dl3 | 236 | 38.5 | 0.65 (0.13) | 0.12 | 0.09–0.14 | 42.4 |

| Lipid-lowering therapy prescribed to eligible | 236 | 38.4 | 0.76 (0.14) | 0.21 | 0.16–0.25 | 22.0 |

| Post-MI: with β-blocker | 194 | 3.1 | 0.84 (0.06) | 0.19 | 0.02–0.36 | 24.3 |

| Eligible pts prescribed antiplatelet therapy | 236 | 38.5 | 0.48 (0.15) | 0.15 | 0.12–0.18 | 31.2 |

| BP control (CAD/DM/CHF/HTN) | ||||||

| CVD: BP<140/90 mmHg3 | 236 | 70.3 | 0.62 (0.11) | 0.09 | 0.07–0.11 | 54.9 |

| CHD, HTN and DM: annual creatinine test done | 236 | 70.1 | 0.82 (0.14) | 0.22 | 0.18–0.26 | 20.0 |

| Heart disease: functional status assessed | 236 | 43.1 | 0.59 (0.42) | 0.87 | 0.84–0.9 | 0.9 |

| Diabetes care | ||||||

| Annual A1c test done | 235 | 28.6 | 0.82 (0.13) | 0.24 | 0.19–0.29 | 18.0 |

| With HbA1C<7%‡ | 235 | 28.3 | 0.44 (0.11) | 0.09 | 0.07–0.11 | 58.2 |

| Annual eye exam documented | 235 | 28.6 | 0.19 (0.14) | 0.28 | 0.23–0.33 | 14.6 |

| Annual complete foot exam documented | 235 | 28.6 | 0.10 (0.19) | 0.65 | 0.58–0.72 | 3.0 |

| Annual urine protein test done | 235 | 23.7 | 0.44 (0.32) | 0.61 | 0.56–0.67 | 3.6 |

| On an ACE or ARB | 162 | 4.3 | 0.79 (0.11) | 0.25 | 0.1–0.4 | 16.6 |

| Congestive heart failure | ||||||

| Weight documented | 220 | 6.4 | 0.90 (0.13) | 0.47 | 0.35–0.58 | 6.5 |

| Annual left ventricular function assessment | 220 | 6.4 | 0.46 (0.15) | 0.22 | 0.14–0.29 | 20.4 |

| On an ACE or ARB | 146 | 2.3 | 0.85 (0.07) | 0.26 | 0.02–0.5 | 16.2 |

| With β-blocker | 167 | 2.5 | 0.83 (0.11) | 0.34 | 0.12–0.57 | 10.8 |

| Eligible pts prescribed Warfarin therapy | 154 | 2.3 | 0.67 (0.11) | 0.23 | 0.03–0.43 | 19.1 |

| Osteoarthritis | ||||||

| Functional status assessed | 233 | 20.1 | 0.61 (0.41) | 0.87 | 0.84–0.91 | 0.8 |

| On anti-inflammatory medications | 233 | 20.1 | 0.7 (0.19) | 0.32 | 0.27–0.38 | 11.9 |

| With pain assessment | 233 | 20.1 | 0.5 (0.33) | 0.63 | 0.57–0.69 | 3.3 |

| With level of pain documented | 233 | 20.1 | 0.16 (0.23) | 0.65 | 0.58–0.72 | 3.1 |

| Upper respiratory infection | ||||||

| Appropriate (no) antibiotic use | 234 | 19.6 | 0.45 (0.26) | 0.42 | 0.36–0.48 | 7.9 |

| Appropriate use of nasal decongestants | 165 | 3.8 | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.52 | 0.25–0.79 | 5.2 |

| Urinary tract infection (females only) | ||||||

| With complete relevant history | 236 | 8.7 | 0.50 (0.34) | 0.70 | 0.63–0.76 | 2.5 |

| Appropriate antibiotic use | 227 | 6.8 | 0.17 (0.28) | 0.80 | 0.73–0.87 | 1.4 |

| Antibiotic treatment for LE 7 days | 230 | 7.7 | 0.74 (0.2) | 0.44 | 0.35–0.53 | 7.2 |

| Low back pain | ||||||

| Essential physical documented | 235 | 15.6 | 0.14 (0.19) | 0.56 | 0.48–0.64 | 4.4 |

| History red flags documented | 235 | 15.6 | 0.37 (0.37) | 0.80 | 0.76–0.85 | 1.4 |

| Physical red flags documented | 235 | 15.6 | 0.41 (0.39) | 0.82 | 0.78–0.87 | 1.2 |

| No drugs prescribed | 235 | 15.6 | 0.86 (0.10) | 0.24 | 0.18–0.3 | 17.9 |

| No narcotics prescribed | 235 | 15.6 | 0.66 (0.16) | 0.23 | 0.18–0.28 | 19.3 |

| Advised to avoid prolonged bed rest | 235 | 15.6 | 0.07 (0.21) | 0.86 | 0.81–0.91 | 0.9 |

| No unnecessary imaging | 228 | 10.4 | 0.46 (0.18) | 0.26 | 0.2–0.32 | 15.9 |

| Major depression | ||||||

| Receiving initial therapy | 150 | 5.9 | 0.74 (0.33) | 0.80 | 0.7–0.9 | 1.4 |

| Receiving 6-month course of therapy | 150 | 5.9 | 0.64 (0.37) | 0.83 | 0.75–0.91 | 1.2 |

| No inappropriate therapy | 152 | 6.8 | 0.62 (0.29) | 0.61 | 0.5–0.72 | 3.6 |

| Prevention | ||||||

| Pts advised to exercise | 235 | 43.5 | 0.58 (0.3) | 0.58 | 0.53–0.64 | 4.1 |

| Weight reduction for eligible | 236 | 57.4 | 0.18 (0.16) | 0.39 | 0.33–0.45 | 8.8 |

| Smoking cessation counseling | 233 | 10.8 | 0.62 (0.27) | 0.52 | 0.44–0.59 | 5.3 |

| Flu shot for eligible | 236 | 60.6 | 0.40 (0.27) | 0.48 | 0.43–0.53 | 6.1 |

| Pneumococcal shot for eligible | 236 | 60.6 | 0.38 (0.28) | 0.51 | 0.46–0.56 | 5.4 |

| Mammography screening age ≥40 | 236 | 49.9 | 0.61 (0.21) | 0.28 | 0.23–0.32 | 14.9 |

| Colorectal cancer screening for ≥50 | 236 | 71.1 | 0.49 (0.23) | 0.31 | 0.27–0.35 | 12.5 |

| Osteoporosis screening for ≥65 females | 236 | 25.8 | 0.55 (0.26) | 0.42 | 0.36–0.48 | 7.9 |

Cluster size  , where

, where  and

and  are the mean and variance of number of patients per physician, and K is the number of physicians; therefore, n0 is slightly less than simple average, when number of patients are not same across physicians.

are the mean and variance of number of patients per physician, and K is the number of physicians; therefore, n0 is slightly less than simple average, when number of patients are not same across physicians.

Sample size of patients (N) needed for a reliability (of the mean) for the measure of 0.85.

Outcome measures.

CI, confidence interval; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficients.

The ICCs for the outcome measures were all roughly 0.10 (Table 3). The ICCs for the process measures were more variable but on average substantially higher than those for the outcome measures. Table 3 indicates that for risk-adjusted measures, 14 out of 23 chronic care measures, 11 out of 15 acute care measures, and 8 out of 8 prevention measures had sufficient sample size. For example, 18 patients with diabetes are needed to reliably (ρ = 0.85) measure whether the annual A1c test was done; the observed cluster size was about 29.

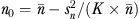

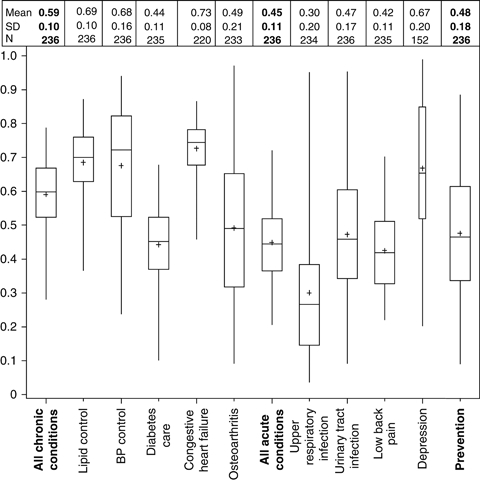

Physician Performance across Measures

Figure 1 shows the box plots and descriptive statistics of composite performance scores. The width of box plots indicates the number of physicians with a performance score available. Performance compliance scores for disease conditions ranged from 30 percent (upper respiratory infection) to 73 percent (congestive heart failure). The mean performance score for chronic conditions (59 percent) was the highest among the three care categories.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Physician Performance Composite Scores

Table 4 displays the risk-adjusted Pearson correlation matrix for the mean physician-level performance across the chronic care, acute care, and preventive services measures (upper triangle) and the measure reliabilities (main diagonal). The majority of the coefficients between the chronic care conditions show moderate levels of correlation, and performance on the chronic care conditions correlated moderately with performance on the preventive services composite (r = 0.66). However, performance on the composite measure for the acute care conditions was less correlated with performance on either the chronic care (r = 0.32) or the preventive services composite measures (r = 0.24).

Table 4.

Correlation and Reliability Matrix for Physician-Level Performance Including Composite Measures*

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chronic condition composite | 0.88 | 0.69 | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.59 | 0.83 | 0.32 | 0.10 | 0.28 | 0.38 | 0.06 | 0.66 |

| 2 | Lipid and treatments (CAD and DM) | 0.58 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.13 | −0.01 | 0.58 | |

| 3 | BP control (CAD/DM/CHF/HTN) | 0.77 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.73 | 0.29 | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 0.44 | ||

| 4 | Diabetes measures | 0.72 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 0.01 | 0.57 | |||

| 5 | Congestive heart failure | 0.55 | 0.32 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.35 | ||||

| 6 | Osteoarthritis | 0.85 | 0.40 | 0.16 | 0.30 | 0.39 | 0.15 | 0.49 | |||||

| 7 | Acute condition composite | 0.85 | 0.20 | 0.71 | 0.83 | 0.61 | 0.24 | ||||||

| 8 | Upper respiratory infection | 0.70 | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.04 | |||||||

| 9 | Urinary tract infection (women only) | 0.73 | 0.52 | 0.19 | 0.23 | ||||||||

| 10 | Low back pain | 0.72 | 0.22 | 0.28 | |||||||||

| 11 | Depression | 0.78 | 0.03 | ||||||||||

| 12 | Preventive care composite | 0.87 |

Note. Estimates along the main diagonal are composite reliabilities.

Pearson correlation coefficient adjusted for age, comorbidity index, race/ethnicity, and gender.

Physician Performance and External Validity

The overall performance (r = 0.19), chronic care (r = 0.14), and preventive care (r = 0.17) composites were all significantly (p <.05) correlated with higher scores on the internal medicine certification examination. We did not find significant associations between the acute care composite and performance on the examination.

DISCUSSION

This study, using well-tested measurement across multiple conditions, highlights the complexity in comprehensively measuring individual physician quality using existing performance measures. However, the high correlation among the chronic disease composite measures and consequent robust reliability of the physician-level composite for chronic diseases suggests that we may now be able to measure quality of chronic care feasibly and reliably. Our finding of significant associations between performance on a knowledge examination and the overall, chronic and preventive care composites provides validity evidence for these composites and is consistent with recent studies finding associations between certification and chronic and preventive care measures (Pham et al. 2005; Holmboe et al. 2008; Turchin et al. 2008;).

Our findings also provide guidance on the utility of comprehensively measuring the effectiveness of new models of primary care such as the patient-centered medical home. Currently, practices are qualified based only on the presence or absence of systems components (ACP 2007; NCQA 2010;). However, the public and policy makers will want evidence new practice models are truly providing high-quality, cost-efficient care across a spectrum of clinical care. The overall, chronic and preventive care composite measures potentially provide very reliable and valid measures of physician and practice performance, and allows for a compensatory approach to measure performance given the substantial between- and within-physician variation.

There are several possible explanations for the physician-level variability on the individual measures, specific conditions, and for composite chronic, acute, and preventive care measures. First, physicians may simply possess varying degrees of knowledge and skill to care for the conditions examined in this study (Palmer et al. 1996). Second, lack of sufficient documentation for underuse measures may partially explain some of the findings (Luck et al. 2000; Peabody et al. 2000; Holmboe et al. 2010;). However, there was clear evidence through documentation that physicians engaged in substantial overuse of procedures and therapies in the acute care domain. Third, some physicians' office systems may be more suitably configured to execute common tasks such as immunizations and test ordering for chronic conditions, but not well designed to provide care for the same patients needing acute care (Stewart 1995).

Fourth, unlike many of the chronic and preventive care measures, most of the acute care measures require a different level of physician clinical judgment (e.g., proper clinical evaluation and diagnosis to inform a decision to order an antibiotic for a respiratory infection). Patients also play a role, such as how insistent they may be in requesting a drug or imagining study; these interactions, however, require physician knowledge and skills to effectively negotiate and communicate with these patients (Kaplan et al. 1996; Duffy et al. 2004; Lipner et al. 2007;). Given the importance of managing acute care conditions, the lack of association of the acute care composite with the other composites, and no apparent relationship to physician competence in knowledge and time spent in practice highlight the urgent need for more research to understand how physicians and their offices deal with acute care conditions and how best to measure performance in this domain.

A few additional caveats are important to note. The likelihood composite measures represent a singular or similar quality construct diminishes as more diverse conditions are included in the composite. Moreover, comprehensive composites may not be most useful for guiding quality improvement initiatives. Physicians will require their results on individual performance measures to guide quality improvement efforts.

What are the potential implications of this study? First, our results provide evidence on the feasibility of obtaining sufficient sample sizes across multiple conditions in a physician's practice. Our results in this limited and likely motivated cohort suggest that it is unlikely, at least for general internists, that a single “blueprint” for comprehensive practice assessment is feasible or even desired using existing performance measures; composite measures and measurement over longer periods of time may address some of these challenges if the goal is to differentiate between physicians. The most encouraging area for further development of composite measures, based on our results, is of the quality of chronic and preventive care.

From a policy perspective, these results may have salience to several accountability approaches being used to improve care. First, P4P programs should consider evolving to more comprehensive assessment, including the use of composite measures but also targeting other important areas of care such as communication and coordination. The Bridges-to-Excellence program has taken a small step in this direction through its advanced medical home program that will require a level of performance in two of its clinical recognition programs (diabetes, heart/stroke, and spine care) and the provider practice connections systems assessment (Conway 2008). Other P4P providers should explore more comprehensive, compensatory models for their programs because a singular focus may fail to uncover other opportunities for improvement in a practice.

Early research also suggests that improvement in performance is concentrated on those measures that are actively monitored (Asch et al. 2004). A comprehensive assessment may help physicians identify the unintended consequences of focusing on only one condition for additional financial reward. Investigators and policy makers implementing and studying new primary care practice models should carefully consider how they will define “success” in these programs. Measurement of limited aspects of practice is not consistent with the goal of improving the delivery of high-quality comprehensive care, especially for patients with multiple conditions (Boyd et al. 2005).

This study has several limitations. First, the goal of this study was not to sample the “universe” of general internists but rather to investigate the feasibility, reliability, and validity of comprehensive assessment using existing and accepted performance measures. As such, the sample size is modest at 236 physicians, who were relatively young, were given compensation for their participation, and all were involved in maintenance of certification program. Thus, nonrepresentativeness of all general internists across the career spectrum is a limitation of this study. However, we sampled broadly across the United States and our results did show substantial variability in the physicians' practice populations and practice performance.

Second, our use of a medical record audit to measure performance is dependent on the quality of documentation. However, medical record audit is a validated approach to measurement and allowed standardization of the audit process across practices regardless of the format of the medical record. We also used a highly rigorous process with several layers of quality control, and the effects of under and overreporting help to offset each other (Peabody et al. 2000). The medical record audit was also labor intensive, making our approach difficult to implement outside of a research setting. However, we found a medical record audit approach produced high reliabilities (e.g., >0.85) for a number of single measures as well as our composites using very feasible sample sizes not seen in studies relying on claims data (Scholle et al. 2008; Sequist et al. 2010;).

Our results strengthen the argument for the urgent need to build performance measurement into electronic medical records to enable comprehensive assessment of performance (DesRoches et al. 2008). However, some of the important measures used in this study, such as functional status, are currently difficult to generate electronically yet are clinically meaningful, necessitating some amount of “hand” audit for the foreseeable future if we truly want to assess the quality of care comprehensively. While the traditional medical record audit must give way to electronically generated data, it will be some time before health information technology can generate comprehensive performance assessment at the point of care. Perhaps more important, our study provides guidance on how data should be structured to ensure health information technology provides clinically meaningful data not just to policy makers, payers, and so forth, but to help physicians improve their care. For example, validated templates or structured questions that capture important aspects of care such as functional status, and so forth, should be built into the EMRs with appropriate links to key demographic data and tracked through an ongoing registry. EMRs should also investigate software used in qualitative research that can accurately search strings of key text.

In conclusion, comprehensive assessment of individual physicians is a challenging but important task as the country embarks on health care reform, especially in primary care. Our data demonstrate how difficult it can be for physicians to perform well across multiple conditions. However, and perhaps most important, our results suggest that the creation of composite measures, especially in chronic disease and preventive care, may be a more reliable, fair, and valid way to discriminate performance across heterogeneous physicians' patient populations if such performance measurement remains a part of P4P programs and is publicly reported. New approaches to comprehensive assessment are needed to better inform the public about the quality of the care they receive in primary care practices and should be sensitive to the changes that occur in the microsystems (ACP 2007; NCQA 2010;). However, in the end what matters most are the outcomes experienced by patients, and measuring just delivery system changes is likely insufficient (Holmboe et al. 2010). This study shows that a broader sampling of practice across multiple conditions may be a reasonable first step, and our approach could be used to evaluate the effectiveness of patient-centered medical home demonstration projects and other primary care redesign initiatives.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: Drs. Holmboe, Arnold, Weng, and Lipner and Ms. Hood are employed by the American Board of Internal Medicine, and Dr. Eric S. Holmboe, MD, receives partial salary support from the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. Drs. Kaplan, Greenfield, and Normand received financial support from the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation.

Financial Support: American Board of Internal Medicine and American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. Bridges-to-Excellence provided funding for an expert panel meeting related to this project.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimers: None.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix SA2. Measures for Comprehensive Care Project.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

REFERENCES

- Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ) 2005. “National Healthcare Quality Report” [accessed on January 4, 2010]. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/nhqr05/nhqr05.htm.

- American College of Physicians (ACP) 2007. “Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home” [accessed on January 4, 2010]. Available at http://www.acponline.org/advocacy/where_we_stand/medical_home/approve_jp.pdf.

- Asch SM, McGlynn EA, Hogan MM, Hayward RA, Shekelle P, Rubenstein L, Keesey J, Adams J, Kerr EA. Comparison of Quality of Care for Patients in the Veterans Health Administration and Patients in a National Sample. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;141:938–45. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-12-200412210-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T. Coordinating Care—A Perilous Journey through the Health Care System. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358:1064–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0706165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW. Clinical Practice Guidelines and Quality of Care for Older Patients with Multiple Comorbid Diseases: Implications for Pay for Performance. Journal of American Medical Association. 2005;294:716–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell S, Reeves D, Kontopantelis E, Middleton E, Sibbald B, Roland M. Quality of Primary Care with the Introduction of Pay for Performance. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:181–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr065990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) 2008. “Physician Quality Reporting Initiative” [accessed January 4, 2010]. Available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/pqri/

- Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a Combined Comorbidity Index. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1994;47(11):1245–51. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway C. 2008. “Bridges to Excellence Launches Medical Home Program” [accessed on January 4, 2010]. Available at http://www.bridgestoexcellence.org/Content/ContentDisplay.aspx?ContentID=119.

- DesRoches CM, Campbell EG, Rao SR, Donelan K, Ferris TG, Jha A, Kaushal R, Levy DE, Rosenbaum S, Shields AE, Blumenthal D. Electronic Health Records in Ambulatory Care—A National Survey of Physicians. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359(1):50–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0802005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy FD, Gordon GH, Whelan G, Cole-Kelly K, Frankel R, Buffone N, Lofton S, Wallace M, Goode L, Langdon L. Participants in the American Academy on Physician and Patient's Conference on Education and Evaluation of Competence in Communication and Interpersonal Skills. Assessing Competence in Communication and Interpersonal Skills: The Kalamazoo II Report. Academic Medicine. 2004;79(6):495–507. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200406000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldt LS, Brennan RL. Chapter 3: Reliability. In: Lynn RL, editor. Educational Measurement. 3d Edition. New York: American Council on Education and Macmillan Publishing Company; 1989. pp. 105–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hasnain-Wynia R, Baker DW, Nerenz D, Feinglass J, Beal AC, Landrum MB, Behal R, Weissman JS. Disparities in Health Care Are Driven by Where Minority Patients Seek Care: Examination of the Hospital Quality Alliance Measures. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167(12):1233–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer TP, Hayward RA, Greenfield S, Wagner EH, Kaplan SH, Manning WG. The Unreliability of Individual Physician Report Cards for Assessing the Costs and Quality of Care of a Chronic Disease. Journal of American Medical Association. 1999;281:2098–105. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.22.2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmboe ES, Wang Y, Meehan TP, Tate JP, Ho S-Y, Starkey KS, Lipner RS. Association between Maintenance of Certification M Examination Scores and Quality of Care for Medicare Beneficiaries. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168:1396–403. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmboe ES, Wang Y, Tate JP, Meehan TP. The Effects of Patient Volume on the Quality of Diabetic Care for Medicare Beneficiaries. Medical Care. 2006;44(12):1073–7. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000233685.22497.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmboe ES, Arnold GK, Weng W, Lipner R. Current Yardsticks May Be Inadequate for Measuring Quality Improvements from the Medical Home. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2010;29(5):859–66. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Gandek B, Rogers W, Ware JE., Jr Characteristics of Physicians with Participatory Decision-Making Styles. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1996;24:497–504. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-5-199603010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan SH, Griffith JL, Price LL, Pawlson LG, Greenfield S. Improving the Reliability of Physician Performance Assessment: Identifying the “Physician Effect” on Quality and Creating Composite Measures. Medical Care. 2009;47:378–87. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818dce07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr EA, Asch SM, Hamilton EG, McGlynn EA. Quality of Care for General Medical Conditions. A Review of the Literature and Quality Indicators. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Landon BE, Normand SL, Blumenthal D, Daley J. Physician Clinical Performance Assessment: Prospects and Barriers. Journal of American Medical Association. 2003;290:1183–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.9.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landon BE, Normand S-LT. Performance Measurement in the Small Office Practice: Challenges and Potential Solutions. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148:353–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-5-200803040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TH. Pay for Performance, Version 2.0? New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:531–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipner RS, Weng W, Arnold GK, Duffy FD, Lynn LA, Holmboe ES. A Three-Part Model for Measuring Diabetes Care in Physician Practice. Academic Medicine. 2007;82(10 suppl):S48–52. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31814027b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck J, Peabody JW, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M, Glassman P. How Well Does Chart Abstraction Measure Quality? A Prospective Comparison of Standardized Patients with the Medical Record. American Journal of Medicine. 2000;108:642–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A, Kerr EA. The Quality of Health Care Delivered to Adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348(26):2635–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) 2010. “Physicians Practice Connections: Patient-Centered Medical Home” [accessed January 4, 2010]. Available at http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/631/Default.aspx.

- National Quality Forum (NQF) 2008. “Core Documents: Currently NQF-Endorsed Measures” [accessed January 4, 2010]. Available at http://www.qualityforum.org/

- Nelson EC, Batalden PB, Huber TP, Johnson JK, Godfrey MM, Headrick LA, Wasson JH. Success Characteristics of High-Performing Microsystems. Learning from the Best. In: Nelson EC, Batalden PB, Godfrey MM, editors. Quality by Design: A Clinical Microsystems Approach. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2007. pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer HR, Wright EA, Orav EJ, Hargraves JL, Louis TA. Consistency in Performance among Primary Care Practitioners. Medical Care. 1996;34:52–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199609002-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M. Comparison of Vignettes, Standardized Patients, and Chart Abstraction. Journal of American Medical Association. 2000;283:1715–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.13.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham HH, Schrag D, Hargraves JL, Bach PB. Delivery of Preventive Services to Older Adults by Primary Care Physicians. Journal of American Medical Association. 2005;294:473–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.4.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves D, Campbell SM, Adams J, Shekelle PG, Kontopantelis E, Roland M. Combining Multiple Indicators of Clinical Quality. Medical Care. 2007;45(6):489–96. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31803bb479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholle SH, Roski J, Adams JL, Dunn DL, Kerr EA, Dugan DP, Jensen RE. Benchmarking Physician Performance: Reliability of Individual Composite Measures. American Journal of Managed Care. 2008;14(12):833–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequist TD, Schneider EC, Li A, Rodgers WH, Safran DG. Reliability of Medical Group and Physician Performance Measurement in the Primary Care Setting. Medical Care. 2010;48(6):553–7. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d5690f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart MA. Effective Physician–Patient Communication and Health Outcomes: A Review. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1995;152:1423–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchin A, Shubina M, Chodos AH, Einbinder JS, Pendergrass ML. Effect of Board Certification on Antihypertensive Treatment Intensification in Patients with Diabetes. Circulation. 2008;117:623–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.733949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JG, Meterko M, Beckman H, Baker E, White B, Sautter KM, Greene R, Curtin K, Bokhour BG, Berlowitz B, Burgess JF. Effects of Paying Physicians Based on Their Relative Performance for Quality. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:872–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0185-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.