Abstract

The transcription factors T-bet and GATA3 determine the differentiation of helper T cells into Th1 or Th2 cells, respectively. An altered ratio of their relative expression promotes the pathogenesis of certain immunological diseases, but whether this may also contribute to the pathogenesis of antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR) versus T cell-mediated rejection (TCMR) is unknown. Here, we characterized the intragraft expression of T-bet and GATA3 and determined the correlation of their levels with the presence of typical lesions of ABMR and TCMR. We found a predominant intraglomerular expression of T-bet in patients with ABMR, which was distinct from that in patients with TCMR. In ABMR, interstitial T-bet expression was typically located in peritubular capillaries, although the overall quantity of interstitial T-bet was less than that observed in TCMR. The expression of intraglomerular T-bet correlated with infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes, which express T-bet, as well as intraglomerular CD68+ monocyte/macrophages, which do not express T-bet. The predominance of intraglomerular T-bet expression relative to GATA3 expression associated with poor response to treatment with bolus steroid. In summary, predominance of intraglomerular T-bet expression correlates with antibody-mediated rejection and resistance to steroid treatment.

Although renal transplantation is the optimal renal-replacement therapy for patients with end-stage renal failure,1 acute rejection remains a barrier to long-term allograft survival. Both T cells and alloantibodies can lead to renal allograft damage through T cell-mediated rejection (TCMR) and antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR), respectively. These two effector mechanisms have been well recognized for decades but remain far from being fully elucidated.2,3

Two transcription factors, T-box expressed in T cells (T-bet) and GATA3, are key determinants of T-helper cell differentiation into Th1 or Th2, respectively.4,5 Changes in the ratio of expression of T-bet/GATA3 have been implicated in determining the eventual pathogenesis of a number of immunological diseases.6–8 T-bet was shown to be an indicator of acute cellular rejection in 2005.9 Moreover, the predominance of intraglomerular T-bet has also been observed in patients with antibody-mediated chronic rejection and transplant glomerulopathy.10,11 We hypothesized that changes in the expression of T-bet and GATA3 might relate to the pathogenesis of the two types of renal allograft rejection, ABMR and TCMR. This study was performed to determine whether changes of either T-bet or GATA3 expression account for the development of ABMR and TCMR.

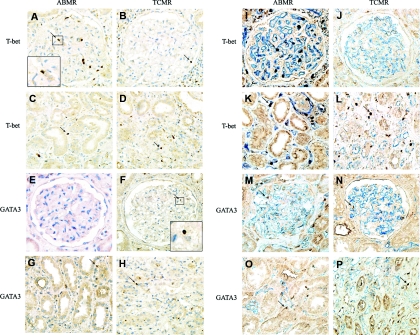

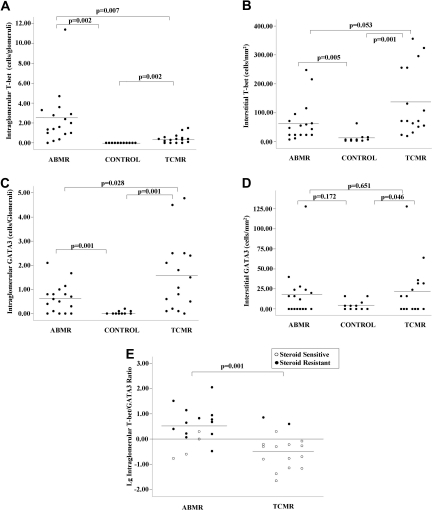

Forty-four renal allograft recipients were included in this study, including 17 patients with ABMR, 16 patients with TCMR, and 11 patients with normal graft function as controls. The diagnosis of ABMR and TCMR was based on Banff 2001.12 The clinical characteristics of the recipients who developed acute rejection are listed in Table 1. Renal biopsies were assessed for intragraft expression of T-bet and GATA3 transcription factors by immunohistochemistry. T-bet and GATA3 expression was detected on lymphocytes within the glomeruli and in interstitial inflammation and tubular epithelial cells (Figure 1). It is interesting that GATA3 expression could also be detected in some podocytes. Intraglomerular T-bet expression could be detected in 94.1% of the ABMR group and 75% of the TCMR group, whereas it was detected in none of the control group. Intraglomerular GATA3 expression could be detected in 76.5% of the ABMR group and in 93.5% of the TCMR group. Only three (27.3%) recipients in the control group had scattered intraglomerular GATA3 expression. Costaining with CD31 (to highlight capillaries) showed that T-bet expression was located in the capillary loops of the glomerular in both groups, whereas GATA3 expression was mainly located within the mesangial area (Figure 1). Compared with the TCMR group, the level of intraglomerular T-bet expression was significantly higher in the ABMR group (Figure 2) (2.41 ± 2.65 versus 0.42 ± 0.44 cells/glomerulus, P = 0.007), whereas the level of intraglomerular GATA3 expression was significantly lower in the ABMR group (Figure 2) (0.64 ± 0.6 versus 1.59 ± 1.49 cells/glomerulus, P = 0.028). Thus, in the glomeruli, there was a higher ratio of T-bet/GATA3 expression in the ABMR group relative to the TCMR group. T-bet expression was predominant in 76.5% of the ABMR group compared with only 18.8% of the TCMR group (P = 0.001).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients and their renal allografts with acute rejection

| ABMR (n = 17) | TCMR (n = 16) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical features | |||

| gender, male (%) | 5 (29%) | 12 (75%) | 0.023 |

| age (years) | 40.47 ± 8.81 | 34.75 ± 11.72 | 0.122 |

| positive pretransplant PRA | 0 | 0 | |

| previous transplant | 0 | 0 | |

| induction with IL-2R antibody | 17 | 16 | |

| baseline immunosuppressants | |||

| MMF + Tac + Pred | 17 | 16 | |

| others | 0 | 0 | |

| onset of rejection postsurgery, median (range) | 4 days (2 days to 1.5 months) | 14 days (4 days to 9 months) | |

| Histological lesions | |||

| PTC inflammation, n (%) | 17 (100%) | 9 (56%) | 0.003 |

| PTC score | 2.12 ± 0.78 | 0.81 ± 0.75 | <0.001 |

| glomerulitis, n (%) | 17 (100%) | 10 (62.5%) | 0.072 |

| glomerulitis score | 2.18 ± 0.88 | 0.69 ± 0.6 | <0.001 |

| tubulitis, n (%) | 13 (76.5%) | 16 (100%) | 0.103 |

| tubulitis score | 0.88 ± 0.60 | 1.93 ± 0.85 | <0.001 |

| intimal arteritis, n (%) | 11 (64.7%) | 7 (43.8%) | 0.303 |

| intimal score | 0.76 ± 0.66 | 0.63 ± 0.88 | 0.610 |

| Immunohistological analysis | |||

| intraglomerular | |||

| T-bet (cells/glomerulus) | 2.41 ± 2.65 | 0.42 ± 0.44 | 0.007 |

| GATA3 (cells/glomerulus) | 0.64 ± 0.6 | 1.59 ± 1.49 | 0.028 |

| T-bet/GATA3 ratio >1 | 13 (76.5%) | 3 (18.8%) | 0.001 |

| CD4 (cells/glomerulus) | 1.14 ± 1.24 | 0.3 ± 0.49 | 0.017 |

| CD8 (cells/glomerulus) | 1.96 ± 1.91 | 0.41 ± 0.44 | 0.004 |

| CD68 (cells/glomerulus) | 8.64 ± 7.44 | 1.56 ± 2.59 | 0.001 |

| Interstitial | |||

| T-bet (cells/mm2) | 68.24 ± 68.48 | 137.00 ± 117.38 | 0.053 |

| GATA3 (cells/mm2) | 18.12 ± 31.01 | 23.25 ± 33.51 | 0.651 |

| T-bet/GATA3 ratio >1 | 13 (76.5%) | 15 (93.8%) | 0.166 |

| CD4 (cells/mm2) | 242.94 ± 142.40 | 312.25 ± 139.81 | 0.169 |

| CD8 (cells/mm2) | 221.18 ± 116.84 | 498.88 ± 828.27 | 0.181 |

| CD68 (cells/mm2) | 645.41 ± 373.40 | 626.44 ± 471.86 | 0.899 |

PRA, panel-reactive antibody; Pred, prednisolone.

Figure 1.

Intragraft T-bet and GATA3 expression is different in renal allografts with different mechanisms of acute rejection. Positive staining is labeled with a brown color. (A) Intraglomerular T-bet expression in ABMR. (B) Intraglomerular T-bet expression in TCMR. (C) Interstitial T-bet expression in ABMR. (D) Interstitial T-bet expression in TCMR. (E) Intraglomerular GATA3 expression in ABMR, which is negative in this case. (F) Intraglomerular GATA3 expression in TCMR. (G) Interstitial GATA3 expression in ABMR. (H) Interstitial GATA3 expression in TCMR. Compared with TCMR group, the quantity of intraglomerular T-bet was higher, whereas GATA3 was lower in the ABMR group. In contrast, the amount of interstitial T-bet was lower in the ABMR group. (I through P) Costaining with CD31 (to highlight capillaries) shows the location of T-bet and GATA3. In the ABMR group, the majority of T-bet+ cells were located in the peritubular capillaries area; however, in the TCMR group, T-bet+ cells were scattered within the interstitial area. The incidence of interstitial GATA3 was similar in both ABMR and TCMR groups. Magnification was ×400 (+ enlarged image).

Figure 2.

The predominance of intragraft T-bet or GATA3 correlates with different mechanisms of acute rejection and different responses to steroid treatment. (ABMR, n = 17; TCMR, n = 16; control, n = 11). (A) Quantitative measurement of the number of intraglomerular T-bet expression in acute rejection. (B) Quantification of interstitial T-bet expression (cells/mm2) in graft biopsies displaying acute rejection. (C) Quantitative measurement of intraglomerular GATA3 expression in acute rejection (cells/glomerulus). (D) Quantification of interstitial GATA3 expression (cells/mm2) in graft biopsies displaying acute rejection. (E) Ratio of intraglomerular T-bet/GATA3 (log) in acute rejection and its relationship with response to steroid treatment. To calculate the ratio, values of less than 0.1 cell/glomerulus were recorded as 0.1 cell/glomerulus. The black circles represent steroid-resistant cases, and the white circles represent steroid-sensitive cases.

In contrast, the level of interstitial T-bet expression was not significantly different between the two groups; it seems that the T-bet expression was even higher in TCMR group (68.24 ± 68.48 versus 137.00 ± 117.38/mm2, P = 0.053) (Figure 2). However, the pattern of cell scattering was quite different as shown by costaining with CD31 (Figure 1). In the ABMR group, the majority of T-bet+ cells were typically located in the peritubular capillaries (PTC). However, in the TCMR group, although T-bet+ cells could be detected in PTC, they were also scattered within the interstitial area. The expression of interstitial GATA3 was similar in both ABMR and TCMR groups (Figure 1).

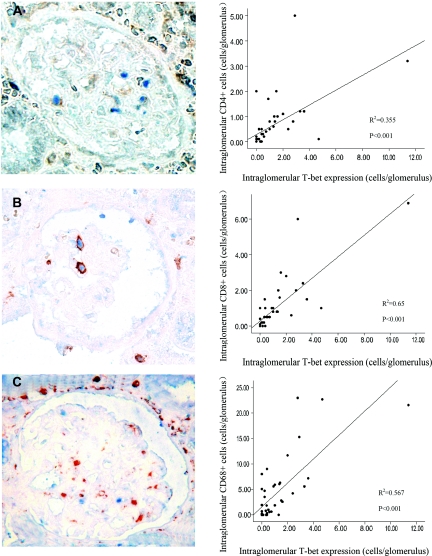

To analyze the nature of intraglomerular infiltration, we performed CD4, CD8, and CD68 staining using paraffin-embedded slides. The numbers of intraglomerular CD4+, CD8+, and CD68+ T cells were all significantly higher in the ABMR group compared with the TCMR group (P = 0.017, 0.004, and 0.001, respectively). The intraglomerular expression of T-bet correlated well with glomerular CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocyte infiltration (Figure 3). Costaining of T-bet with CD4 and CD8 showed that T-bet was expressed in intraglomerular CD4+ and CD8+ cells (Figure 3). Although no CD68+ cells coexpressed T-bet, the intraglomerular expression of T-bet was strongly correlated with intraglomerular CD68+ cell infiltration (P < 0.001; Figure 3); the more T-bet expression, the more CD68+ cells were detected.

Figure 3.

Intraglomerular T-bet expression strongly correlates with CD4+, CD8+, or CD68+ cell infiltration. (A) Costaining of T-bet (blue) and CD4 (brown) and scatter plot to the right demonstrating the correlation between T-bet and CD4. (B) Costaining of T-bet (blue) and CD8 (brown), scatter plot demonstrating correlation between T-bet and CD8. (C) Costaining of T-bet (blue) and CD68 (brown), and scatter plot to the right demonstrating correlation between T-bet and CD68. T-bet was expressed in some of the CD4+ or CD8+ cells and was correlated with CD4+ and CD8+ cell count. Although no CD68+ cells coexpressed T-bet, the intraglomerular expression of T-bet was strongly correlated with intraglomerular CD68+ cell infiltration. Magnification was ×400.

The predominance of intraglomerular T-bet relative to GATA3 expression was strongly correlated with poor response to bolus steroid treatment. Patients with a poor response to steroid had a higher T-bet/GATA3 ratio than patients who responded. Only two patients (12.5%, two of 16) with rejection episodes with T-bet predominance (including one patient in the TCMR group) had a positive response to steroid treatment, and seven patients received immunoadsorption treatment. In contrast, all but one (94.1%, 16 of 17) of the rejection episodes in patients with GATA3 predominance (T-bet/GATA3≦1) could be reversed with steroid treatment (P < 0.0001), including three patients with ABMR (Figure 2E). Expression of T-bet, as determined by the T-bet/GATA3 ratio, appears correlated with response to steroid treatment. In the ABMR group, all of the three patients with an average expression of T-bet <0.5 cells/glomerulus responded to steroid treatment. In contrast, two recipients with high ratio of intraglomerular T-bet/GATA3 in the TCMR group had no response to steroid treatment. Although four patients with T-bet expression between 0.5 and 1.0 cells/glomerulus could be controlled by steroid, the response was not as quick as that with T-bet expression <0.5 cells/glomerulus. The only patient to lose a graft due to rejection had high intraglomerular T-bet expression (4.7 cells/glomerulus) and a high T-bet/GATA3 ratio (6.71). Overall, these results suggest that the higher the intraglomerular T-bet expression, the more difficult the rejection episode is to control with steroids.

This is the first study, to our knowledge, that compares changes of the T-bet/GATA3 expression in TCMR and ABMR after renal transplantation. We show that predominance of intraglomerular T-bet expression is associated with ABMR, whereas predominance of intraglomerular GATA3 is associated with TCMR. The ratio of T-bet/GATA3 expression was also strongly correlated with the response to steroid treatment.

Our study suggests that the ratio of intraglomerular T-bet/GATA3 could be used to differentiate between ABMR and TCMR; we showed a significant difference in the ratio of intraglomerular T-bet/GATA3 between ABMR and TCMR (Figure 2E). Current diagnosis of ABMR largely depends on C4d staining.12–15 However, accumulating evidence suggests that C4d deposition occurs in some but not all ABMRs.16,17 Conversely, C4d can also be detected in grafts with stable function.18 Thus, the ratio of intragraft T-bet/GATA3 could be a useful adjunct to C4d staining in the diagnosis ABMR. Our findings are at least consistent with intraglomerular T-bet predominance in chronic ABMR reported by Ashton-Chess et al.,10 although GATA3 expression was not assessed in that study. The key difference in T-bet/GATA3 expression in ABMR and TCMR is not on the overall quantity but the localization. This may explain why a previous study10 did not find any difference in T-bet mRNA between the ABMR and TCMR groups assessed. Actually, even in interstitial area, T-bet is typically located within the PTC in ABMR (Figure 1K).

Nevertheless, our study suggests that intraglomerular expression of T-bet/GATA3 could be used to individualize treatment. The intraglomerular T-bet/GATA3 ratio appears to be correlated with response to steroid treatment. T-bet predominance was related to resistance to steroid treatment, whereas GATA3 predominance was related to steroid sensitivity. Our observation combined with the knowledge that some C4d-positive rejections can be easily reversed with anti-T-cell therapy19,20 may represent important first steps toward personalizing ABMR treatment on the basis of biopsy histology.

Intraglomerular T-bet predominance may be used, in part, to explain the pathogenesis of glomerulitis, a typical lesion of ABMR. Because T-bet expression can be detected in CD4+ and CD8+ cells, it was therefore not surprising to observe that the expression of T-bet was correlated with the number of intraglomerular CD4+ and CD8+ cells. Interestingly, T-bet expression was also correlated with glomerular CD68+ cells infiltration. Because Th1 responses can induce macrophage and cytotoxic T lymphocyte activation,21 our finding of the predominance of intraglomerular Th1 transcription factor expression in ABMR is of significance in explaining the pathogenesis of glomerulitis. It is highly possible that Th1 cells promote the infiltration of CD68+ cells. Accumulating evidence suggests that CD68+ cells play an important role in the development of ABMR.22–24 Clarifying the relation between intracapillary T-bet and CD68+ cells infiltration will add to our understanding of the pathogenesis of ABMR.

T-bet and GATA3 are key determinants of T-helper cell differentiation into Th1 or Th2, respectively. It is possible that T-bet and GATA3 expression affects the mechanism of rejection via Th1 and Th2 pathway. However, T-bet and GATA3 are not exclusively expressed in T cells. Under certain conditions, T-bet expression can also be detected in B cells,10 and our data showed GATA3 can be expressed on podocytes, which was consistent with a previous in vitro observation.25 Thus, the role of T-bet and GATA3 in acute rejection may not be limited to the regulation of Th1 and Th2 response; their exact roles in the control of other cell types remains to be clarified.

In conclusion, our preliminary study suggests that changes in the predominance of T-bet or GATA3 expression may lead to the development of either ABMR or TCMR. Predominance of intraglomerular T-bet was associated with antibody-mediated injury and resistance to steroid treatment. Detection of intragraft T-bet and GATA3 expression may be helpful to determine an appropriate treatment strategy for acute rejection.

CONCISE METHODS

Patient Selection

Forty-four renal allograft recipients were included in this study, including 17 patients with ABMR, 16 patients with TCMR, and 11 patients with normal graft function as controls. The patients were selected from 340 renal allograft recipients transplanted between January 2006 and June 2010 in Jinling Hospital, Nanjing University School of Medicine, Nanjing, China. All of the rejection episodes were confirmed by renal biopsy. The diagnosis of ABMR and TCMR were based on BANFF 2001 criteria.12 Acute rejection episodes with C4d staining but without detectable donor-specific antibodies or those with detectable donor-specific antibodies but without C4d staining were excluded from this study. Except for ABMR, which was correlated with female gender, there were no significant differences between groups in recipient age, induction and maintenance immunosuppressants, and time to onset of rejection. Informed consent was obtained from all patients, and the Human Subjects Committee of Jinling Hospital, Nanjing University School of Medicine approved all of the study protocols.

Renal Biopsies

Diagnostic biopsies were performed after onset of presumed rejection. Two needle biopsy cores were obtained from each renal allograft for morphologic study: one for formalin fixation and the other for quick-freezing. Hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid Schiff, methenamin-silver, and Masson stains were routinely used on the formalin-fixed tissue. The residual biopsy tissues were stored for future use. Fresh frozen tissue was analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy using a conventional panel of antibodies against IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, C4, C1q, and C4d. C4d staining was routinely performed on frozen slides, using an indirect immunofluorescence technique with a primary affinity-purified monoclonal antibody (mouse anti-human; dilution, 1:50; 1.5 h of incubation at room temperature; Quidel, San Diego, CA) and an FITC-labeled affinity-purified secondary rabbit anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:20; 40 minutes of incubation at room temperature; Dako). Staining was performed according to standard procedures. A positive C4d staining was defined as bright linear stain along capillary basement membranes, involving over half of the sampled capillaries according to the 2001 Banff meeting.

Immunohistological Analysis

CD4, CD8, and CD68 were regularly detected when biopsy performed. The intragraft expression of T-bet and GATA3 was retrospectively studied via immunohistochemistry using stored residual biopsy tissues. Immunohistochemistry was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. Regimens included: mouse monoclonal antibody to T-bet (H-210, sc-21003; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); rabbit polyclonal to GATA3 (ab61168; Abcam, Cambridge, UK); and mouse monoclonal antibodies to CD4 (NCL-CD4-1F6; Novocastra, Newcastle, UK), CD8 (NCL-CD8-295; Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK), CD68 (KP1; Dako, Carpinteria, CA), and CD31 (M0823; Dako). The sections were reviewed by two separate pathologists, and the results were expressed as total number of positive cells per glomerulus or per square millimeter in the cortex. The staining of T-bet and GATA3 were highly repeatable in sequential sections (data not shown) and were very faithful to T-bet and GATA3 mRNA levels (Spearman r = 0.778, P = 0.001; r = 0.922, P < 0.001, respectively).

Treatment of Acute Rejection

Once a rejection episode had occurred, bolus corticosteroid therapy (methylprednisolone at 500 mg/d for 3 days) was selected as first-line treatment. Concomitantly, all of the patients were given mycophenolate mofetil (MMF; 1.5 g/d) and tacrolimus (Tac; trough levels maintained at 8–15 ng/ml). For patients being treated with Tac, MMF, and steroids as primary immunosuppression, the dose of Tac was increased so that trough levels were maintained at 8–15 ng/ml. If patients needed dialysis, continuous veno-venous hemofiltration was performed. Immunoadsorption was used for seven patients with high level of antibodies or very strong and diffuse C4d staining.

Statistical Methods

The descriptive statistical values are expressed as the means ± SD. Between-group differences in frequencies of clinical characteristics were determined using the Fisher exact test. The analyses were done using SPSS 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Correlations between T-bet expression and CD4+, CD8+, and CD68+ cells were evaluated by Pearson correlation analysis. A P value of 0.05 or less was considered significant.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the General Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 81070593 and 30600572). Part of this work was presented at the 2010 American Transplant Congress in San Diego, California, May 1 to 5, 2010. English-language editing was provided by Richard Glover of Wolters Kluwer with the financial support of by Shanghai Roche Pharmaceutical Ltd.

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Prof. Lei-Shi Li, who passed away on March 16, 2010.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, Held PJ, Port FK: Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med 341: 1725–1730, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Colvin RB: Antibody-mediated renal allograft rejection: Diagnosis and pathogenesis. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1046–1056, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Terasaki PI, Cai J: Humoral theory of transplantation: Further evidence. Curr Opin Immunol 17: 541–545, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Noble A: Review article: Molecular signals and genetic reprogramming in peripheral T-cell differentiation. Immunology 101: 289–299, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Farrar JD, Asnagli H, Murphy KM: T helper subset development: Roles of instruction, selection, and transcription. J Clin Invest 109: 431–435, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Neurath MF, Weigmann B, Finotto S, Glickman J, Nieuwenhuis E, Iijima H, Mizoguchi A, Mizoguchi E, Mudter J, Galle PR, Bhan A, Autschbach F, Sullivan BM, Szabo SJ, Glimcher LH, Blumberg RS: The transcription factor T-bet regulates mucosal T cell activation in experimental colitis and Crohn's disease. J Exp Med 195: 1129–1143, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chan RW, Lai FM, Li EK, Tam LS, Chow KM, Li PK, Szeto CC: Imbalance of Th1/Th2 transcription factors in patients with lupus nephritis. Rheumatology 45: 951–957, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Finotto S, Neurath MF, Glickman JN, Qin S, Lehr HA, Green FH, Ackerman K, Haley K, Galle PR, Szabo SJ, Drazen JM, De Sanctis GT, Glimcher LH: Development of spontaneous airway changes consistent with human asthma in mice lacking T-bet. Science 295: 336–338, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hoffmann SC, Hale DA, Kleiner DE, Mannon RB, Kampen RL, Jacobson LM, Cendales LC, Swanson SJ, Becker BN, Kirk AD: Functionally significant renal allograft rejection is defined by transcriptional criteria. Am J Transplant 5: 573–581, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ashton-Chess J, Dugast E, Colvin RB, Giral M, Foucher Y, Moreau A, Renaudin K, Braud C, Devys A, Brouard S, Soulillou JP: Regulatory, effector, and cytotoxic T cell profiles in long-term kidney transplant patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1113–1122, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Homs S, Mansour H, Desvaux D, Diet C, Hazan M, Buchler M, Lebranchu Y, Buob D, Badoual C, Matignon M, Audard V, Lang P, Grimbert P: Predominant Th1 and cytotoxic phenotype in biopsies from renal transplant recipients with transplant glomerulopathy. Am J Transplant 9: 1230–1236, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Racusen LC, Colvin RB, Solez K, Mihatsch MJ, Halloran PF, Campbell PM, Cecka MJ, Cosyns JP, Demetris AJ, Fishbein MC, Fogo A, Furness P, Gibson IW, Glotz D, Hayry P, Hunsickern L, Kashgarian M, Kerman R, Magil AJ, Montgomery R, Morozumi K, Nickeleit V, Randhawa P, Regele H, Seron D, Seshan S, Sund S, Trpkov K: Antibody-mediated rejection criteria: An addition to the Banff 97 classification of renal allograft rejection. Am J Transplant 3: 708–714, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Solez K, Colvin RB, Racusen LC, Haas M, Sis B, Mengel M, Halloran PF, Baldwin W, Banfi G, Collins AB, Cosio F, David DS, Drachenberg C, Einecke G, Fogo AB, Gibson IW, Glotz D, Iskandar SS, Kraus E, Lerut E, Mannon RB, Mihatsch M, Nankivell BJ, Nickeleit V, Papadimitriou JC, Randhawa P, Regele H, Renaudin K, Roberts I, Seron D, Smith RN, Valente M: Banff 07 classification of renal allograft pathology: Updates and future directions. Am J Transplant 8: 753–760, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nickeleit V, Mihatsch MJ: Kidney transplants, antibodies and rejection: Is C4d a magic marker? Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 2232–2239, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mauiyyedi S, Crespo M, Collins AB, Schneeberger EE, Pascual MA, Saidman SL, Tolkoff-Rubin NE, Williams WW, Delmonico FL, Cosimi AB, Colvin RB: Acute humoral rejection in kidney transplantation: II. Morphology, immunopathology, and pathologic classification. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 779–787, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sis B, Jhangri GS, Bunnag S, Allanach K, Kaplan B, Halloran PF: Endothelial gene expression in kidney transplants with alloantibody indicates antibody-mediated damage despite lack of C4d staining. Am J Transplant 9: 2312–2323, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Einecke G, Sis B, Reeve J, Mengel M, Campbell PM, Hidalgo LG, Kaplan B, Halloran PF: Antibody-mediated microcirculation injury is the major cause of late kidney transplant failure. Am J Transplant 9: 2520–2531, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Haas M, Segev DL, Racusen LC, Bagnasco SM, Locke JE, Warren DS, Simpkins CE, Lepley D, King KE, Kraus ES, Montgomery RA: C4d deposition without rejection correlates with reduced early scarring in ABO-incompatible renal allografts. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 197–204, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sun Q, Liu ZH, Cheng Z, Chen J, Ji S, Zeng C, Li LS: Treatment of early mixed cellular and humoral renal allograft rejection with tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil. Kidney Int 71: 24–30, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nickeleit V, Zeiler M, Gudat F, Thiel G, Mihatsch MJ: Detection of the complement degradation product C4d in renal allografts: Diagnostic and therapeutic implications. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 242–251, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Holdsworth SR, Kitching AR, Tipping PG: Th1 and Th2 T helper cell subsets affect patterns of injury and outcomes in glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 55: 1198–1216, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Magil AB: Infiltrating cell types in transplant glomerulitis: Relationship to peritubular capillary C4d deposition. Am J Kidney Dis 45: 1084–1089, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tinckam KJ, Djurdjev O, Magil AB: Glomerular monocytes predict worse outcomes after acute renal allograft rejection independent of C4d status. Kidney Int 68: 1866–1874, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Magil AB, Tinckam K: Monocytes and peritubular capillary C4d deposition in acute renal allograft rejection. Kidney Int 63: 1888–1893, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xing CY, Saleem MA, Coward RJ, Ni L, Witherden IR, Mathieson PW: Direct effects of dexamethasone on human podocytes. Kidney Int 70: 1038–1045, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]