Abstract

Rationale: Epidemiologic data demonstrate that individuals exposed to low levels of tobacco smoke have decrements in lung function and higher risk for lung disease compared with unexposed individuals. Although this risk is small, low-level tobacco smoke exposure is so widespread, it is a significant public health concern.

Objectives: To identify biologic correlates of this risk we hypothesized that, compared with unexposed individuals, individuals exposed to low levels of tobacco smoke have biologic changes in the small airway epithelium, the site of the first abnormalities associated with smoking.

Methods: Small airway epithelium was obtained by bronchoscopy from 121 individuals; microarrays were used to assess genome-wide gene expression; urine nicotine and cotinine were used to categorize subjects as “nonsmokers,” “active smokers,” and “low exposure.” Gene expression data were used to determine the threshold and induction half maximal level (ID50) of urine nicotine and cotinine at which the small airway epithelium showed abnormal responses.

Measurements and Main Results: There was no threshold of urine nicotine without a small airway epithelial response, and only slightly above detectable urine cotinine threshold with a small airway epithelium response. The ID50 for nicotine was 25 ng/ml and for cotinine it was 104 ng/ml.

Conclusions: The small airway epithelium detects and responds to low levels of tobacco smoke with transcriptome modifications. This provides biologic correlates of epidemiologic studies linking low-level tobacco smoke exposure to lung health risk, identifies the genes most sensitive to tobacco smoke, and defines thresholds at which the lung epithelium responds to low levels of tobacco smoke.

Keywords: threshold, exposure, dose-dependant, ID50

AT A GLANCE COMMENTARY.

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Active smokers are at risk for developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchogenic carcinoma. Individuals exposed to low-dose tobacco smoke from the environment or occasional smoking are also at risk for developing respiratory symptoms.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Analysis of the small airway epithelial transcriptome of individuals exposed to low-dose tobacco smoke compared to those not exposed demonstrates biologic changes that are likely the earliest biologic abnormalities in the lung leading to lung disease.

Although it is well recognized that active smokers with more than 20 pack-year smoking history are at high risk for the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchogenic carcinoma, there is extensive epidemiologic data that individuals exposed to low levels of tobacco smoke, whether from the environment or from smoking only occasionally, are also at risk for developing respiratory symptoms, a decrement in lung function, and clinically apparent lung diseases (1–6). Although the risk is small for this low-exposure group, the public health impact of exposure to low levels of tobacco smoke is significant because the exposed population is large (7, 8). The lung is redundant and often the exposed individuals or their physicians have no idea that the lung is at risk and, because mild loss of lung function has little effect on everyday activities, conventional lung function testing and imaging are not sensitive to early abnormalities (1, 2).

It is evident that exposure to low levels of tobacco smoke is associated on a population basis with a risk to the lung. Therefore, on an individual level, there must be abnormal biologic correlates in lung cells of those exposed to tobacco smoke compared with those not exposed. Based on the knowledge that the airway epithelium, the pseudostratified population of cells lining the bronchial tree from the trachea to the alveoli, are the first lung cells to encounter inhaled smoke, that the airway epithelium responds to active smoking with up- and down-regulation of hundreds of genes, and that the small airway epithelium is the first cell population to exhibit abnormalities in chronic smokers (9–12), we hypothesized that individuals exposed to low levels of tobacco smoke should have differences in gene expression in the small airway epithelium compared with those not exposed to tobacco smoke.

To assess this hypothesis, we sampled pure populations of the small airway epithelium in 121 individuals, all with normal lung function and normal chest radiographs. The subjects were grouped based on urine levels of nicotine and its derivative, cotinine, as “nonsmokers,” “active smokers,” and individuals with “low level smoke exposure.” As the biologic measure of the effect of tobacco smoke on the small airway epithelium, the whole genome transcriptome was assessed using microarrays.

The data demonstrate that individuals with low levels of tobacco smoke exposure do have biologic changes in their small airway epithelium distinct from those not exposed to tobacco smoke. Consistent with epidemiologic data, the threshold of tobacco smoke metabolites at which these biologic changes can be detected is very low, demonstrating that small airway epithelium is very sensitive to low levels of tobacco smoke. It is likely that changes in the small airway epithelium transcriptome identify the earliest biologic abnormalities in the lung that eventually lead to clinically detectable lung disease in some individuals exposed to low levels of tobacco smoke.

METHODS

Study Population

Healthy nonsmokers, healthy smokers, and healthy individuals exposed to low levels of tobacco smoke were recruited from the general population in New York City by posting advertisements in local newspapers and on electronic bulletin boards. All individuals were evaluated at the Weill Cornell NIH Clinical and Translational Science Center and Department of Genetic Medicine Clinical Research Facility, using Institutional Review Board–approved clinical protocols. All were determined to be healthy based on a history, physical examination, complete blood count, coagulation studies, liver function tests, urine studies, chest radiograph, electrocardiogram, and pulmonary function tests. All individuals were negative for HIV1 and had normal α1-antitrypsin levels (for full inclusion–exclusion criteria, see online supplement). Urine nicotine and cotinine levels were determined using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (ARUP laboratories, Salt Lake City, UT [13]) (see Figure E1 in the online supplement). “Nonsmokers” (n = 40) were defined as self-reported lifelong nonsmokers, with nondetectable urine nicotine (<2 ng/ml) and cotinine (<5 ng/ml); “active smokers” (n = 45) as smokers with urine nicotine or cotinine levels greater than 1,000 ng/ml (13); and “individuals with low levels of tobacco exposure” (n = 36) as those exposed to environmental tobacco smoke or with occasional smoking, but with both nicotine and cotinine levels between undetected and 1,000 ng/ml. No individuals in this group were exsmokers. No subjects smoked within 12 hours before bronchoscopy procedure to collect small airway epithelium.

Sampling the Small Airway Epithelium, RNA and Microarray Processing

Small airway epithelium (10th–12th generation) was collected using flexible bronchoscopy as previously described (12). Cells were removed from the brush by flicking into 5 ml of ice-cold LHC8 medium (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY), with 4.5 ml immediately processed for RNA extraction and 0.5 ml to determine the number and types of cells recovered. The expression of genes encoding surfactant and Clara cell secretory proteins confirmed the samples were small airway epithelium (12). RNA was then extracted and processed from the recovered cells using HG-U133 Plus 2.0 arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) to assess genome-wide mRNA transcripts as previously described (see online supplement) (12). The raw data are publically available at the Gene Expression Omnibus Web site (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), accession number GSE19667.

Microarray Data Analysis

Using the MAS5 algorithm (GeneSpring version 7.3, Affymetrix Microarray Suite Version 5), the data were normalized per chip to the median expression value of each sample. Genome-wide analysis was used to compare the expression in healthy active smokers with healthy nonsmokers. Genes significantly modified by smoking were selected based on (1) P call “Present” in ≥ 20% of healthy nonsmokers, and healthy active smokers' samples (14); (2) ≥1.5 fold-change in average expression for healthy active smokers versus healthy nonsmokers (12); and (3) P less than 0.01 with Benjamini-Hochberg correction to limit the false–positive rate (15). This generated a list of 612 probe sets representing 372 known and unique genes that were significantly differentially expressed between all healthy active smokers and all healthy nonsmokers. These genes were functionally annotated using the NetAffx Analysis Center (www.affymetrix.com) to retrieve gene ontology annotations.

Principal Component Analysis

Global patterns of expression of the 372 small airway epithelium smoking-responsive genes were examined using principal component analysis. Intuitively, a principal component analysis identifies combinations of genes that vary together and compactly summarizes variation in such gene sets with a set of composite measurements or principal components (16), which technically are orthogonal superpositions of the individual genes. The first principal component (PC1) accounts for the maximum variation in the entire set of 372 genes (i.e., the most optimal linear summary of the expression profiles of the 372 genes in the small airway epithelium) (17).

Correlation of Gene Expression with Levels of Urine Nicotine and Cotinine

The relationship between gene expression of smoke-induced genes and urine nicotine and cotinine levels was examined individually and summarized with PC1 using a growth model for the dose–response curve (18). Specifically, a sigmoid function in the form of a generalized logistic curve was applied,

|

where the expression is y for a log10 nicotine/cotinine value of x, yns is the mean value of y for nonsmokers, and ys the mean y for smokers. The sigmoid function captures a less extreme response to lower dosages, which then gives way to more extreme response as the dosage passes a critical level, an appropriate model for dosage response. The sigmoid function was fit using a standard nonlinear least-square algorithm for parameters B and M. A linear “no threshold” model was also considered but excluded because the correlations were only r2 = 0.17 for nicotine and r2 = 0.4 for cotinine (compared with r2 = 0.72 and 0.8, respectively, for the sigmoid function). The sigmoid models were examined for threshold levels of nicotine and cotinine that had a significant change in expression from the nonsmokers, as defined by changes larger than 1 SD away from the mean of nonsmokers; and the half maximum level of induction or induced dose 50% (ID50), defined in analogy with the often used lethal dose 50% (LD50) or effective dose 50% (ED50). The latter is the point along the curve where the expression values are half-way between the mean of the active smokers and mean of nonsmokers (18).

Pathway Analysis

To determine which pathways are affected by smoking, Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (Redwood City, CA) was used to establish which pathways are enriched with the 372 smoking–responsive genes. The canonical pathways that are enriched according to the software analysis program are chosen on the basis of a ratio of smoking-responsive genes involved in the pathway compared with the total number of genes in the curated pathway and significance (−log P value) based on the association between the smoking-responsive genes list and the given pathway.

RESULTS

The study population of nonsmokers, individuals exposed to low levels of tobacco smoke, and active smokers were comparable in sex, age, and race (Table 1). All had normal lung function. The numbers and purity of the small airway epithelium were comparable, as were the types of epithelial cells recovered. The nonsmokers had undetectable urine nicotine and cotinine levels (Table 1). The low-level exposure group included self-reported never smokers (8 of 36) and those who reported some smoking (28 of 36). Analysis of history of smoking (pack-years) showed that the lowest quartile had a history of 0.1 ± 0.3 pack-years (Table 1). For the low-level exposure group, on the average, the urine nicotine was 192 ± 247 ng/ml (median, 55 ng/ml; range, 2–741 ng/ml), and the urine cotinine was 404 ± 340 ng/ml (median, 326; range, 5–992); these values likely include a combination of occasional smoking or exposure to smoke in the environment. As expected, there was a good correlation between the urine nicotine and cotinine levels (r2 = 0.84; P < 10−16) (see Figure E1).

TABLE 1.

DEMOGRAPHICS OF THE STUDY POPULATION AND BIOLOGIC SAMPLES*

| Parameters | Healthy Nonsmokers | Healthy Individuals Exposed to Low Levels of Tobacco Smoke | Healthy Active Smokers |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 40 | 36 | 45 |

| Sex, M/F | 24/16 | 22/14 | 33/12 |

| Age, yr | 39.9 ± 14.1 | 39.8 ± 8.4 | 42.5 ± 8.6 |

| Race, B/W/O† | 17/14/9 | 21/7/8 | 26/11/8 |

| Active smokers | 29 ± 12 | ||

| Low-level tobacco exposure | |||

| Pack-yr, lowest quartile | 0.1 ± 0.3 | ||

| Pack-yr, 25–50% quartile | 9 ± 3.9 | ||

| Pack-yr, 50–75% quartile | 20.6 ± 2.3 | ||

| Pack-yr, top quartile | 37 ± 14.1 | ||

| Urine nicotine, ng/ml‡ | Negative | 203 ± 249 | 2,022 ± 1,680 |

| Urine cotinine, ng/ml‡ | Negative | 428 ± 336 | 1,876 ± 1,023 |

| Pulmonary function parameters§ | |||

| FVC | 107 ± 14 | 109 ± 13 | 111 ± 13 |

| FEV1 | 105 ± 14 | 107 ± 14 | 109 ± 14 |

| FEV1/FVC | 81 ± 6 | 81 ± 4 | 80 ± 5 |

| TLC | 100 ± 14 | 101 ± 15 | 101 ± 11 |

| DlCO | 99 ± 16 | 98 ± 14 | 92 ± 9 |

| Epithelial cells‖ | |||

| Number recovered x106 | 6.6 ± 2.3 | 6.9 ± 3.5 | 7.9 ± 3.5 |

| Epithelial cells, % | 98.6 ± 1.5 | 99.3 ± 1 | 98.5 ± 1.7 |

| Inflammatory cells, % | 1.4 ± 1.5 | 0.7 ± 1 | 1.4 ± 1.7 |

| Differential cell count¶ | |||

| Ciliated, % | 71.5 ± 9.9 | 68.5 ± 10.6 | 61.4 ± 11.9 |

| Secretory, % | 6.4 ± 3.4 | 7.4 ± 3.9 | 8.6 ± 4.5 |

| Basal, % | 12.2 ± 7.4 | 13.7 ± 7.4 | 15.2 ± 8.6 |

| Undifferentiated, % | 8.6 ± 3.5 | 9.9 ± 4.8 | 13.2 ± 7.6 |

Definition of abbreviation: DlCO = diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide.

Data are presented as mean ± SD.

B = black; W = white; O = other.

Undetectable, nicotine <2 ng/ml, cotinine <5 ng/ml.

Pulmonary function testing parameters are given as percent of predicted value with the exception of FEV1/FVC, which is reported as percent observed.

Small airway epithelium.

As a percentage of small airway epithelium recovered.

Small Airway Gene Expression

To identify the genes in the small airway epithelium that are responsive to cigarette smoke, genome-wide expression of the small airway epithelium of the active smokers was compared with nonsmokers. There were 612 probe sets representing 372 unique, known genes, significantly different between these groups (Figure 1A; see Table E1 for a complete list). The expression of these 372 genes was then assessed for individuals exposed to low levels of tobacco smoke compared with the nonsmokers and active smokers. As with the comparison of active versus nonsmokers, there were a significant number of genes up- and down-regulated in the low-level smoke-exposed individuals compared with the nonsmokers (128 [34%] of 372), and a smaller number of smoking-related genes significantly modified in the small airway epithelium of the low-level exposed group versus that of the active group (41 [11%] of 372) (Figure 1B). The gradations in the levels of expression of the smoking-responsive genes from nonsmokers to low-level exposed individuals to active smokers were visualized in cluster plots of expression of the smoking-responsive genes as a function of urine nicotine and cotinine levels (Figures 1C and 1D).

Figure 1.

Differential gene expression profiles in the small airway epithelium in healthy nonsmokers, healthy active smokers, and healthy individuals exposed to low levels of tobacco smoke. Expression levels normalized by array were compared for active smokers (n = 45) and healthy nonsmokers (n = 40) for all probe sets “present” in at least 20% of samples in the Affymetrix HG-U133 Plus 2.0 array. The smoking-responsive probe sets (n = 612) were determined using a criteria of fold-change ≥ 1.5 (calculated as the average expression value of each probe set in all smokers divided by the average expression value in all nonsmokers), and P < 0.01 with Benjamini-Hochberg correction (see Table E1 for the complete list). Out of the 612 smoking-responsive probe sets, there were 372 probe sets representing known and unique genes. (A, B) Volcano plot showing all probe sets present in the small airway epithelium for ≥ 20% of the nonsmokers and active smokers. The fold-change of expression level for active smokers versus nonsmokers (log2, abscissa) is plotted against the P value (ordinate) by t test. Each dot represents a probe set, red dots represent probe sets with a significant difference in expression level, and gray dots represent probe sets not differentially expressed. (A) Active smokers versus nonsmokers, n = 612 probe sets. (B) Individuals exposed to low levels of tobacco smoke versus nonsmokers, n = 128 probe sets out of the 612 smoking-responsive genes. For each panel, genes that are up-regulated in active smokers or individuals exposed to low levels of tobacco smoke are to the top right and those that are down-regulated are to the top left. (C, D) Cluster of expression of smoking-responsive known genes in nonsmokers, active smokers, and smokers exposed to low levels of tobacco smoke. Blue indicates genes with decreased expression, red indicates genes with increased expression, and white indicates genes with average expression. The genes are represented horizontally and sorted by loading on the first principal component; the individual subjects are represented vertically and sorted by levels of either urine nicotine (C) or urine cotinine (D). All of the nonsmokers, active smokers, and individuals exposed to low levels of tobacco are included.

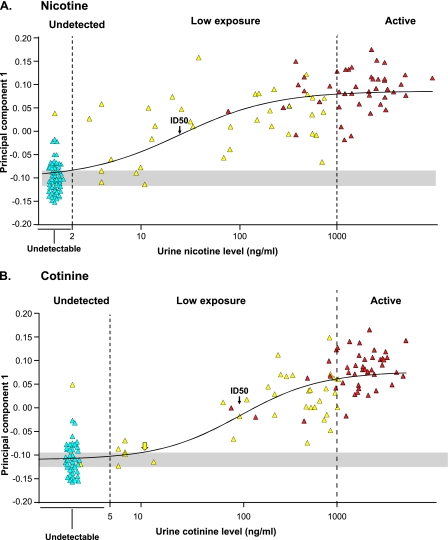

PC1 was used to define the level of urine nicotine and cotinine at which there was a significant change in expression from the nonsmokers. To accomplish this, a sigmoid model was used with all subjects, fitting the subjects' scores on PC1 versus their urine nicotine and cotinine levels (Figure 2). This analysis identified an ID50 (the point along the best fit curve where the PC1 expression values were half-way between the mean of active smokers and nonsmokers) as 25 ng/ml for nicotine and 104 ng/ml for cotinine. The same analysis permitted identification of the threshold of urine nicotine and cotinine at which the best fit curve was significantly different from nonsmokers (>1 SD away from the nonsmokers mean). For urine nicotine, the estimated threshold was 1.8 ng/ml, a level below the detectable level of urine nicotine of 2 ng/ml (i.e., for urine nicotine, there was no detectable level at which the small airway epithelium did not respond with abnormal gene expression). For urine cotinine, the threshold level was 11 ng/ml, just above the detectable limit of 5 ng/ml.

Figure 2.

Comparison of overall small airway gene expression as defined by principal component 1 with levels of urine nicotine and cotinine. Shown is the score of each subject on principal component 1, obtained by decomposing the 372 genes by subjects matrix, versus levels of urine nicotine (A) or urine cotinine (B). In both panels, light blue represents nonsmokers, yellow represents individuals exposed to low levels of tobacco smoke, and red represents active smokers. Samples with undetectable levels of nicotine or cotinine are randomly displayed along the x axis for visualization purposes. The black line shows a best fit sigmoid curve with the half maximal (ID50) point indicated by the arrow (nicotine 25 ng/ml; cotinine 104 ng/ml) and threshold, as determined by the intersection of this line and 1 SD away from the mean of the nonsmokers. For nicotine, the threshold is below the detectable limit; for cotinine it is at 11 ng/ml indicated by the yellow arrow.

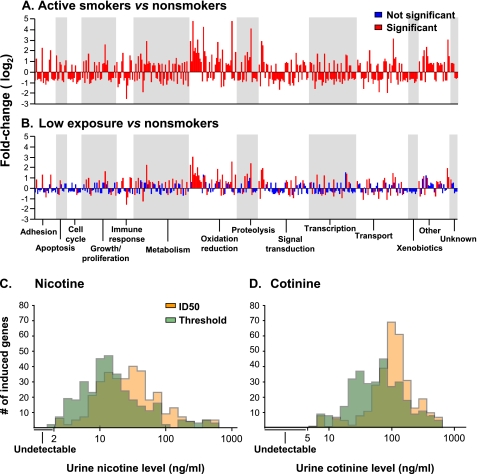

Analysis of the categories of genes significantly different in the low-exposure group compared with the nonsmokers showed a broad distribution, similar to the categories of genes up- and down-regulated in active smokers compared with nonsmokers. However, the low-exposure group expressed genes to a lesser extent with fewer genes in each category (Figure 3A). Analysis of the number of genes that were induced to be up- or down-regulated at the lowest levels of nicotine and cotinine showed a gradual increase starting close to the threshold or ID50 for each gene of detection levels for urine nicotine (Figure 3C) or cotinine (Figure 3D). Further analysis identified which of the 372 smoking-responsive genes responded to the lowest levels of urine nicotine and cotinine levels (i.e., the genes with the lowest threshold and ID50 by fitting the same sigmoid function to individual gene expression). Both the threshold and the ID50 models identified similar lists of genes associated with the lowest levels of urine nicotine levels, with 6 of the 10 top genes identical in both models (Table 2). Among those genes were PLA2G10, phospholipase A2, group X; CXCL6, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 6 and SULT1C4, sulfotransferase family, cytosolic, 1C, member 4. Using the same method to generate a list of genes associated with the lowest levels of urine cotinine levels yielded a list of genes that were mostly different than those associated with urine nicotine levels but 9 of the top 10 genes were the same using the threshold model or the ID50 model (Table 3). Among these genes were CYP2E1, cytochrome P-450, family 2, subfamily E, polypeptide 1; GAD1, glutamate decarboxylase 1; and S100P, S100 calcium binding protein P. The “most sensitive” gene lists were different for nicotine and cotinine, because the nicotine-responding genes likely represent genes relevant to more acute exposure and the cotinine-responding genes relevant to more chronic exposure.

Figure 3.

Genes in the small airway epithelium up- and down-regulated by smoking. (A, B) Categories of genes. Shown are skyscraper plots of fold-changes for the 372 unique, known genes significantly differentially expressed in active smokers versus nonsmokers in the small airway epithelium (P call “Present” in ≥ 20%, 1.5 fold-change up- or down-regulated; P < 0.01, with Benjamini-Hochberg correction). Fold-changes of the 372 smoking-responsive genes are presented on log2 scale. Alternating gray and white bands indicate probe sets that belong to different functional categories. (A) Fold-changes in active smokers (n = 45) versus nonsmokers (n = 40). (B) Fold-changes in individuals exposed to low levels of tobacco smoke (n = 36) versus nonsmokers (n = 40). (C, D) Histogram of threshold and ID50 for all 372 smoke-induced genes as determined by fitting a sigmoid function to the dose–response function for each gene as a function of nicotine and cotinine. Urine nicotine, median threshold 13.1 ng/ml, median ID50 27 ng/ml (C). Urine cotinine, median threshold 65 ng/ml, median ID50 108 ng/ml (D).

TABLE 2.

GENES UP- OR DOWN-REGULATED IN THE SMALL AIRWAY EPITHELIUM ASSOCIATED WITH LOWEST URINE NICOTINE LEVELS IN INDIVIDUALS EXPOSED TO LOW LEVELS OF TOBACCO SMOKE*

| Threshold† |

ID50§ |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Symbol | Gene Title | Biologic Function | Level of Expression Versus Nonsmokers | Rank of Sensitivity‡ | Level (ng/ml) | Rank of Sensitivity‖ | Levels (ng/ml) |

| PLA2G10 | Phospholipase A2, group X | Metabolism | Up | 1 | 2.07 | 1 | 2.10 |

| CXCL6 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 6 | Immune response | Down | 2 | 2.11 | 2 | 2.11 |

| SULT1C4 | Sulfotransferase family, cytosolic, 1C, member 4 | Metabolism | Down | 3 | 2.13 | 3 | 2.13 |

| TBC1D16 | TBC1 domain family, member 16 | Regulation of Rab GTPase activity | Up | 4 | 2.17 | 4 | 2.14 |

| AVPR1A | Arginine vasopressin receptor 1A | Signal transduction | Down | 5 | 2.43 | 5 | 2.43 |

| LMNB1 | Lamin B1 | Growth/proliferation | Down | 6 | 2.44 | 6 | 2.73 |

| GPX2 | Glutathione peroxidase 2 | Oxidation reduction | Up | 7 | 2.46 | 91 | 13.5 |

| ME1 | Malic enzyme 1 | Oxidation reduction | Up | 8 | 2.57 | 131 | 19.5 |

| TXNRD1 | Thioredoxin reductase 1 | Signal transduction | Up | 9 | 2.95 | 114 | 17.6 |

| PIR | Pirin | Transcription | Up | 10 | 2.96 | 54 | 10.3 |

| HOXA1 | Homeobox A1 | Transcription | Up | 17 | 3.21 | 7 | 3.25 |

| ABCA13 | ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A (ABC1), member 13 | Transport | Down | 13 | 3.01 | 8 | 3.57 |

| HEPACAM2 | HEPACAM family member 2 | Unknown | Up | 32 | 3.93 | 9 | 3.99 |

| S100P | S100 calcium binding protein P | Signal transduction | Up | 29 | 3.85 | 10 | 4.09 |

Nondetectable <2 ng/ml.

Threshold is the lowest nicotine level at which the expression level of each gene is greater or smaller than 1 SD of nonsmokers, average level of expression.

Rank of sensitivity is assigned according to the threshold of urine nicotine level at which the expression level of the gene was significantly greater or smaller than 1 SD of the nonsmokers average level of expression (i.e., the gene that is ranked #1 was the most sensitive gene and its expression level was significantly greater or smaller than 1 SD of the nonsmokers' average level at the lowest nicotine level). Genes ranked 13, 17, 32, and 29 were within the top 10 for the ID50.

ID50 is the urine nicotine level at which the average expression of the gene is half-way between nonsmokers and active smokers.

Rank of sensitivity is assigned according to the ID50 level of urine nicotine; genes ranked 54, 91, 114, and 131 were ranked within the top 10 for the thresholds.

TABLE 3.

GENES UP- OR DOWN-REGULATED IN THE SMALL AIRWAY EPITHELIUM ASSOCIATED WITH THE LOWEST URINE COTININE LEVELS IN INDIVIDUALS EXPOSED TO LOW LEVELS OF TOBACCO SMOKE*

| Threshold† |

ID50§ |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Symbol | Gene Title | Biologic Function | Level of Expression Versus Nonsmokers | Rank of Sensitivity‡ | Level (ng/ml) | Rank of Sensitivity‖ | Level (ng/ml) |

| CYP2E1 | Cytochrome P-450, family 2, subfamily E, polypeptide 1 | Oxidation reduction | Down | 1 | 6.22 | 1 | 6.35 |

| GAD1 | Glutamate decarboxylase 1 | Metabolism | Up | 2 | 6.74 | 8 | 7.33 |

| S100P | S100 calcium binding protein P | Signal transduction | Up | 3 | 6.93 | 6 | 7.12 |

| GALNT6 | UDP-N-acetyl-alpha-d-galactosamine: polypeptide N-acetylgalacto-saminyltransferase 6 | Metabolism | Up | 4 | 6.96 | 2 | 6.97 |

| PYCR1 | Pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase 1 | Oxidation reduction | Up | 5 | 7.01 | 3 | 6.98 |

| MYO15B | Myosin XVB pseudogene | Unknown | Down | 6 | 7.04 | 7 | 7.17 |

| GPT2 | Glutamic pyruvate transaminase 2 | Metabolism | Up | 7 | 7.05 | 5 | 7.03 |

| MATN4 | Matrilin 4 | Unknown | Up | 8 | 7.06 | 4 | 7.02 |

| D2HGDH | D-2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase | Oxidation reduction | Down | 9 | 7.51 | 9 | 7.88 |

| PLA2G10 | Phospholipase A2, group X | Metabolism | Up | 10 | 8.77 | 11 | 11.7 |

| WNK4 | WNK lysine deficient protein kinase 4 | Signal transduction | Down | 11 | 9.62 | 10 | 9.99 |

Nondetectable <5 ng/ml.

Threshold is the lowest cotinine level at which the expression level of each gene is greater or smaller than 1 SD of nonsmokers' average level of expression.

Rank of sensitivity is assigned according to the threshold of urine cotinine level at which the expression level of the gene was significantly greater or smaller than 1 SD of the nonsmokers' average level of expression (i.e., the gene that was ranked #1 is the most sensitive gene and its expression level was significantly greater or smaller than 1 SD of the nonsmokers' average level at the lowest cotinine level); the gene ranked 11 was ranked within the top 10 for the ID50.

ID50 is the urine cotinine level at which the average expression of the genes is half-way between nonsmokers and active smokers.

Rank of sensitivity is assigned according to the ID50 level of urine cotinine level; the gene ranked 11 was within the top 10 for the threshold.

To examine the relevance of smoking-responsive genes represented at the lowest levels of tobacco smoke exposure, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis was performed to assess the pathways enriched in the smoking-responsive genes identified in the first quartile (lowest) of nicotine or cotinine levels compared with the pathways enriched in the smoking-responsive genes identified in the active smokers (Table 4). Interestingly, for both nicotine and cotinine, the top two pathways for the lowest quartile of urine metabolites were “metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P-450” and “arachidonic acid metabolism,” the same two pathways at the top of the list for the active smokers. Although this does not prove that these pathways are relevant to the pathogenesis of smoking-induced lung disease, it does support the concept that the small airway epithelium, the initial site of smoking-induced pathology, is responding to low levels of tobacco smoke exposure in a fashion that parallels that in active smokers, albeit to a lesser extent.

TABLE 4.

PATHWAYS ENRICHED IN THE SMALL AIRWAY EPITHELIUM OF INDIVIDUALS EXPOSED TO LOW LEVELS OF TOBACCO SMOKE COMPARED WITH HEALTHY SMOKERS*

| Exposure Group | Pathway | P Value‖ | Ratio (%)¶ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotine, low exposure, lowest quartile (threshold)† | Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P-450 | 2.1 × 10−7 | 3.8 |

| Arachidonic acid metabolism | 6.8 × 10−6 | 3.1 | |

| NRF-2 oxidative stress response | 2.1 × 10−5 | 3.8 | |

| Tryptophan metabolism | 9.2 × 10−5 | 2.4 | |

| Phenylalanine metabolism | 7.3 × 10−4 | 2.8 | |

| Cotinine, low exposure, lowest quartile (threshold)‡ | Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P-450 | 9.5 × 10−7 | 4.3 |

| Arachidonic acid metabolism | 5.6 × 10−6 | 3.1 | |

| Tryptophan metabolism | 7.8 × 10−5 | 2.4 | |

| Fatty acid metabolism | 3.9 × 10−4 | 2.6 | |

| TR/RXR activation | 7.6 × 10−4 | 4.1 | |

| Active smokers§ | NRF-2 oxidative stress response | 1.3 × 10−7 | 9.3 |

| Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P-450 | 5.3 × 10−7 | 6.7 | |

| Glutathione metabolism | 8.5 × 10−6 | 9.2 | |

| Arachidonic acid metabolism | 5.6 × 10−5 | 5.3 | |

| Xenobiotic metabolism signaling | 9.6 × 10−5 | 5.8 |

Ingenuity pathway analysis, each exposure group compared with nonsmokers; shown are the top five pathways in each group.

Urine nicotine 2–7 ng/ml.

Urine cotinine 6–32 ng/ml.

Active smoker, urine nicotine or cotinine >1,000 ng/ml.

A measure of the likelihood that the association between the smoking-responsive genes involved in the pathway and the given pathway is not random.

Number of smoking-responsive genes (out of 372) found in a pathway out of the total number of genes involved in that pathway.

DISCUSSION

There are extensive epidemiologic data describing the risk to lung health of low-level exposure to tobacco smoke, whether from environmental exposure or intermittent smoking (1–3, 5, 6). Together, these data warn of a significant public health issue (i.e., although the risks to lung health are small compared with active chronic smoking, there are large numbers of individuals worldwide exposed to low levels of tobacco smoke, placing significant numbers at risk [2, 7, 8]). Our study focuses the biologic correlate of these epidemiologic data: because there is clinical evidence that the lung is at increased risk of exposure to low levels of tobacco smoke, there must be changes in these individuals in the biology of their small airway epithelium, the cell population central to the pathogenesis of smoking-induced lung disease (9–12). Using genome-wide gene expression as the phenotype and urine nicotine and cotinine levels as the quantitative measure of extent of exposure to tobacco smoke, the data demonstrate that the small airway epithelium is indeed very sensitive to low-level tobacco smoke exposure. Importantly, there was no threshold of urine nicotine levels at which the small airway epithelium showed no response, and the levels of urine cotinine at which the small airway responds is close to the cotinine-detectable threshold. These changes in gene expression are likely the earliest biologic abnormalities in the small airway epithelium that lead to clinically detectable lung disease in some individuals.

Exposure to Low Levels of Tobacco Smoke

Extensive data suggest that exposure to low levels of tobacco smoke in adults is associated with an increased risk for respiratory symptoms, decrement in lung function, and lung disease (1–3, 5–8, 19–22). Exposure to low levels of tobacco smoke is also linked to increased respiratory tract infections, likely by interfering with airway epithelial defenses (1, 8, 23). There are also significant risks to the future lung health of children exposed to low levels of tobacco smoke (24).

Exposure to low levels of tobacco smoke can be from environmental tobacco smoke (side-stream smoke released from the tip of a burning cigarette together with mainstream smoke exhaled by smokers) or by direct exposure when individuals smoke small numbers of cigarettes (7). Two approaches are used to quantify this integrated exposure: questionnaires and quantification of nicotine and its metabolites in body fluids or tissues (25–28). Based on studies demonstrating discrepancies between self-reports of cigarette smoking and measurements of nicotine and its metabolites, we chose the latter to quantify this integrated exposure (25, 26). The alternative (self-reports) is criticized for lack of standardization and variability in individual recall and an unwillingness of some individuals to admit to the extent of smoking, if at all (25). We recognize that the biochemical markers of tobacco exposure, although excellent in distinguishing nonsmokers from active smokers, cannot accurately determine who is an occasional smoker compared with nonsmokers exposed to environmental tobacco smoke (7, 25–27). In this regard, we refer to this group as individuals with “low level smoke exposure” because our main goal was to correlate evidence of low-level exposures to the transcriptome response of the small airway epithelium, not to determine the source of the low exposure (27, 29).

Assessment of nicotine and its metabolites can be done in urine, plasma, or tissue (30). We used urine, with mass spectroscopy, to quantify nicotine and cotinine (13). An average cigarette contains 10–13 mg of nicotine, of which 1–1.5 mg nicotine is absorbed into plasma during smoking of one cigarette, where it is distributed to body tissues (30, 31). Most nicotine is metabolized in the liver where 70–80% is metabolized to cotinine, of which 10–15% appears in the urine (13, 30, 32). The metabolism of nicotine is governed by genetics, age, sex, race/ethnicity/ancestry, diet, pregnancy, and kidney clearance (30). Because of the difference in the half-lives of nicotine (mean, 2 hours in humans) compared with cotinine (mean, 18–20 hours) (25, 32), and the relative stability of cotinine, cotinine levels provide a more standard assessment of smoking status, whereas nicotine provides more acute exposure (30). There is a high correlation of cotinine levels in plasma, saliva, and urine (30).

Biologic Effects of Low Levels of Tobacco Smoke

There are extensive data indicating that current smokers and former smokers have changes in the transcriptome of the airway epithelium (12, 14, 33, 34). However, although human studies have documented that acute and chronic exposure to low levels of tobacco smoke activates inflammatory cells and is associated with markers of systemic inflammation (6), to our knowledge this is the first documentation that exposure to low levels of tobacco smoke is associated with modifications of human lung cell biology. Because this is a cross-sectional study, it is not possible to determine if these changes predict the development of pathology in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, nor if the observed changes in small airway epithelial gene expression associated with low exposure to tobacco smoke are protective, harmful, or both. However, when assessing which pathways are affected by smoking, it was observed that similar pathways are affected by low exposure to tobacco smoke as by active smoking. In addition, these low-level exposures to tobacco smoke changes in the small airway gene expression are occurring at the site of the earliest morphologic changes associated with smoking. Thus, these observations are relevant to public policy, in that it is consistent with the epidemiologic data of the increased risks associated with low exposure to tobacco smoke.

Using the combined nonsmoker, low-level exposure, and active smoker small airway epithelial gene expression data enabled us to establish the dose–dependent relationship of changes of the small airway epithelial transcriptome compared with biochemical quantitative evidence of urine nicotine and cotinine. We observed a saturation of expression of smoke-induced genes for high levels of nicotine and cotinine and a limited range of expression for the same genes for low levels of exposure, leading us to rule out the possibility of a linear nonthreshold model of toxicology (35) in favor of a sigmoidal model that has saturated expression levels for high exposure and conforms better to the data for low levels of exposure (18).

The data demonstrate that there is no threshold above the detectable limit for urine nicotine below which the small airway epithelium does not respond to low levels of tobacco smoke, and the threshold for urine cotinine is just above the detectable level. The list of genes most sensitive to nicotine versus cotinine were quite different, likely reflecting differences in more acute versus more chronic exposure to tobacco smoke. It is not surprising that the small airway epithelium seems to be more sensitive to urine nicotine, because nicotine has a half-life eight to nine times less than cotinine (i.e., urine nicotine likely reflects more recent tobacco smoke exposure and cotinine more chronic exposure). Assessment of the genes most sensitive to low-level exposure to tobacco smoke shows a broad heterogeneity. This heterogeneity is not surprising, because cigarette smoke contains more than 4,000 compounds, for which urine nicotine and cotinine serve only as biomarkers for the extent of exposure (26, 30).

Other than self-reported history, there is no quantitative measure of past history of exposure to low levels of tobacco smoke. By history, the lowest quartile of exposure was less than 1 pack-year, which is consistent with the urine nicotine and cotinine levels. However, it is possible that the individuals with low urine nicotine or cotinine were exposed to higher (or lower) levels of tobacco smoke in the distant past, but there is no technology available to assess this possibility.

Overall, the data demonstrate at the biologic level the high sensitivity of the small airway epithelium to low levels of tobacco smoke. These observations have implications for the exposure of individuals in regard to their risk to lung health, and implications for public health, because large populations of individuals worldwide have exposure to low levels of cigarette smoke (1–3, 5–8, 36).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Fellows of the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Medicine for assistance with screening of subjects and bronchoscopies; D. Dang and M. Teater for expert technical assistance; M. Aquilato, S. Hyde, R. Rapoport, R. Valerio, and M. Yeotsas of our Clinical Operations and Regulatory Affairs for helping with conduct of the study; and T. Virgin-Bryan and N. Mohamed for help in preparing this manuscript. These studies were supported, in part, by Protocol registration number: NCT00224185; www.clinicaltrials.gov.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 HL074326 (R.G.C.), P50 HL084936 (R.G.C.), UL1-RR024996, and K12 RR024997 (A.E.T.), and the Flight Attendant's Medical Research Institute. L.O. was supported, in part, by the Cornell Center for Comparative and Population Genomics.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0294OC on August 6, 2010

Author Disclosure: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Jaakkola MS, Jaakkola JJ. Effects of environmental tobacco smoke on the respiratory health of adults. Scand J Work Environ Health 2002;28:52–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan-Yeung M, Dimich-Ward H. Respiratory health effects of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Respirology 2003;8:131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janson C. The effect of passive smoking on respiratory health in children and adults. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2004;8:510–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.2004 Surgeon General's Report—The Health Consequences of Smoking (accessed October 19, 2010). Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2004/index.htm. 2004.

- 5.Eisner MD, Wang Y, Haight TJ, Balmes J, Hammond SK, Tager IB. Secondhand smoke exposure, pulmonary function, and cardiovascular mortality. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17:364–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flouris AD, Metsios GS, Carrillo AE, Jamurtas AZ, Gourgoulianis K, Kiropoulos T, Tzatzarakis MN, Tsatsakis AM, Koutedakis Y. Acute and short-term effects of secondhand smoke on lung function and cytokine production. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:1029–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pirkle JL, Flegal KM, Bernert JT, Brody DJ, Etzel RA, Maurer KR. Exposure of the US population to environmental tobacco smoke: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988 to 1991. JAMA 1996;275:1233–1240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moritsugu KP. The 2006 Report of the Surgeon General: the health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke. Am J Prev Med 2007;32:542–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cosio M, Ghezzo H, Hogg JC, Corbin R, Loveland M, Dosman J, Macklem PT. The relations between structural changes in small airways and pulmonary-function tests. N Engl J Med 1978;298:1277–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cosio MG, Hale KA, Niewoehner DE. Morphologic and morphometric effects of prolonged cigarette smoking on the small airways. Am Rev Respir Dis 1980;122:265–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hogg JC, Chu F, Utokaparch S, Woods R, Elliott WM, Buzatu L, Cherniack RM, Rogers RM, Sciurba FC, Coxson HO, et al. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2645–2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey BG, Heguy A, Leopold PL, Carolan BJ, Ferris B, Crystal RG. Modification of gene expression of the small airway epithelium in response to cigarette smoking. J Mol Med 2007;85:39–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moyer TP, Charlson JR, Enger RJ, Dale LC, Ebbert JO, Schroeder DR, Hurt RD. Simultaneous analysis of nicotine, nicotine metabolites, and tobacco alkaloids in serum or urine by tandem mass spectrometry, with clinically relevant metabolic profiles. Clin Chem 2002;48:1460–1471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pierrou S, Broberg P, O'Donnell RA, Pawlowski K, Virtala R, Lindqvist E, Richter A, Wilson SJ, Angco G, Moller S, et al. Expression of genes involved in oxidative stress responses in airway epithelial cells of smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:577–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alter O, Brown PO, Botstein D. Singular value decomposition for genome-wide expression data processing and modeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000;97:10101–10106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eckart C, Young G. The approximation of one matrix by another of lower rank. Psychometrika 1936;1:211–218. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Timbrell JA. Fundamentals of toxicology dose response relationships. Principles of biochemistry toxicology, 4th ed. New York: Informa Healthcare USA; 2008. pp. 7–33.

- 19.White JR, Froeb HF. Small-airways dysfunction in nonsmokers chronically exposed to tobacco smoke. N Engl J Med 1980;302:720–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaakkola MS. Environmental tobacco smoke and health in the elderly. Eur Respir J 2002;19:172–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vineis P, Airoldi L, Veglia F, Olgiati L, Pastorelli R, Autrup H, Dunning A, Garte S, Gormally E, Hainaut P, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke and risk of respiratory cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in former smokers and never smokers in the EPIC prospective study. BMJ 2005;330:277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skogstad M, Kjaerheim K, Fladseth G, Gjolstad M, Daae HL, Olsen R, Molander P, Ellingsen DG. Cross shift changes in lung function among bar and restaurant workers before and after implementation of a smoking ban. Occup Environ Med 2006;63:482–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dye JA, Adler KB. Effects of cigarette smoke on epithelial cells of the respiratory tract. Thorax 1994;49:825–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lovasi GS, Roux AV, Hoffman EA, Kawut SM, Jacobs DR Jr, Barr RG. Association of environmental tobacco smoke exposure in childhood with early emphysema in adulthood among nonsmokers: the MESA-lung study. Am J Epidemiol 2010;171:54–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caraballo RS, Giovino GA, Pechacek TF, Mowery PD. Factors associated with discrepancies between self-reports on cigarette smoking and measured serum cotinine levels among persons aged 17 years or older: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Am J Epidemiol 2001;153:807–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wells AJ, English PB, Posner SF, Wagenknecht LE, Perez-Stable EJ. Misclassification rates for current smokers misclassified as nonsmokers. Am J Public Health 1998;88:1503–1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rebagliato M. Validation of self reported smoking. J Epidemiol Community Health 2002;56:163–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Florescu A, Ferrence R, Einarson T, Selby P, Soldin O, Koren G. Methods for quantification of exposure to cigarette smoking and environmental tobacco smoke: focus on developmental toxicology. Ther Drug Monit 2009;31:14–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vartiainen E, Seppala T, Lillsunde P, Puska P. Validation of self reported smoking by serum cotinine measurement in a community-based study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2002;56:167–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benowitz NL, Hukkanen J, Jacob PI. Nicotine chemistry, metabolism, kinetics and biomarkers. In: Henningfield JE, editor. Handbook of experimental pharmacology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2009. pp. 192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Kozlowski LT, Mehta NY, Sweeney CT, Schwartz SS, Vogler GP, Jarvis MJ, West RJ. Filter ventilation and nicotine content of tobacco in cigarettes from Canada, the UK, and the United States. Tob Control 1998;7:369–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tutka P, Mosiewicz J, Wielosz M. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of nicotine. Pharmacol Rep 2005;57:143–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spira A, Beane J, Shah V, Liu G, Schembri F, Yang X, Palma J, Brody JS. Effects of cigarette smoke on the human airway epithelial cell transcriptome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:10143–10148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steiling K, Kadar AY, Bergerat A, Flanigon J, Sridhar S, Shah V, Ahmad QR, Brody JS, Lenburg ME, Steffen M, et al. Comparison of proteomic and transcriptomic profiles in the bronchial airway epithelium of current and never smokers. PLoS ONE 2009;4:e5043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hooker AM, Bhat M, Day TK, Lane JM, Swinburne SJ, Morley AA, Sykes PJ. The linear no-threshold model does not hold for low-dose ionizing radiation. Radiat Res 2004;162:447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellis JA, Gwynn C, Garg RK, Philburn R, Aldous KM, Perl SB, Thorpe L, Frieden TR. Secondhand smoke exposure among nonsmokers nationally and in New York City. Nicotine Tob Res 2009;11:362–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.