Abstract

Lichen planus is a multisystem disease. Often genital involvement is missed or misdiagnosed. It can be rapidly progressive with high patient morbidity. This case highlights the importance of a multidisciplinary approach and the effectiveness of combined surgical and medical treatment with close patient follow-up and support.

Background

Lichen planus is a multisystem disease and so can present to a variety of specialists—dermatologists, rheumatologists, general practitioners, and sexual health clinicians.

The vulvovaginal component can lead to distressing symptoms, distortion of anatomy with vaginal stenosis or obliteration, resulting in loss of sexual function and deterioration in quality of life for the patient.

The disease is chronic in nature so patients require dedicated follow-up, counselling and support.

Unfortunately an accurate diagnosis is often missed or delayed. Increased awareness of the genital aspect of lichen planus is needed and patients with lichen planus should always be questioned about genital symptoms.

Treatment options are limited, but this case highlights the benefit of a combined approach and the success of a novel treatment.

Case presentation

A 60-year-old Caucasian teacher was referred with a 2 year history of vulval and vaginal soreness. A prior diagnosis of lichen sclerosis had been made, but vulval steroid ointment and vaginal oestrogen had failed to alleviate symptoms.

On further questioning the main problem was rapidly progressing dyspareunia, both superficial and deep. Other complaints were excess lacrimation, constipation, dysuria and oral inflammation and ulceration, described as “it feels as if the lining of my mouth is peeling off”.

The patient was on no medication and there was no relevant personal or family history. Sexually transmitted disease and autoimmune screens were negative. The examination revealed no obvious oral ulceration or cutaneous lesions and a normal vulva. The vagina was very erythematous with a narrowed introitus and thin filmy adhesions to the mid third. The examination was extremely painful. A diagnosis of lichen planus was made and the patient scheduled for an examination under anaesthesia, division of vaginal adhesions and biopsies.

At surgery, 2 months later, the vagina had completely occluded secondary to filmy adhesions. The adhesions were digitally divided and biopsies taken. These subsequently confirmed lichen planus. The patient was discharged on 30 mg oral prednisone daily and nightly intravaginal Colifoam (Stafford-Miller Ltd, Welwyn Garden City, Herts, UK) enemas. With support from a dedicated nurse specialist she was able to commence vaginal dilator use in 5–7 days and attempt intercourse in 2–3 weeks.

At review, 4 weeks later in the multidisciplinary gynaecology skin clinic, she was well and able to have full penetrative intercourse with no pain. The vagina was still erythematous but completely patent. The oral prednisone dose was gradually tapered and symptoms are now controlled with intravaginal Colifoam three times a week.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient is seen regularly in the combined gynaecology skin clinic. Currently she has minimal symptoms and a fully patent vagina with no compromise of sexual function. She is still using intravaginal Colifoam.

Discussion

Lichen planus is an inflammatory dermatosis which can affect the skin, nails and all mucous membranes, including the genitalia (figs 1 and 2).1 The aetiology is largely unknown but thought to involve an autoimmune mechanism of activated T cells directed against basal keratinocytes. It is associated with the DR1 HLA class II antigen.2 It can also be drug induced with β-blockers, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, lithium, methyldopa, quinine, carbamazepine and penicillamine all being linked to the condition.3 The cutaneous form is associated with liver disease, especially advanced hepatitis C, with interferon treatment causing exacerbations.3

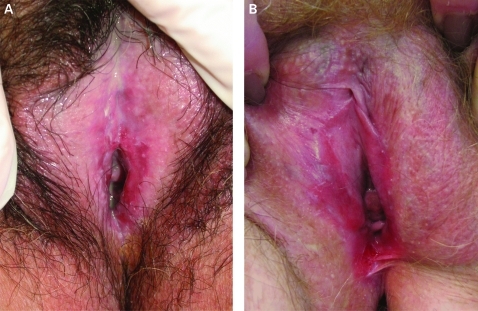

Figure 1.

(A) Erosive vaginal lichen planus. (B) Erosive vaginal lichen planus with fissuring and narrowing of the interoitus. Courtesy of Dr A Oakley.

Figure 2.

Vulval lichen planus showing the typical “lacy” border (Wickham’s striae.) Biopsy is important to exclude vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). Courtesy of Dr J Adams.

This uncommon condition, first described by Erasmus Wilson in 1839, represents 1% of new referrals to dermatology clinics.2 All age groups are affected with incidence peaking in the sixth decade.4 It is more frequent in females, with 50% having vulvovaginal involvement. This presents with vulval soreness, burning, pruritis, dyspareunia, post-coital bleeding, persistent and copious vaginal discharge, dysuria or difficulty in urinating. Often these symptoms are incorrectly attributed to persistent candidiasis.

Three types of lichen planus can affect the vulva/vagina.3

Papulosquamous—Small pruritic papules; involves keratinised and perianal skin.

Hypertrophic—Rarest form with appearances similar to vulval squamous cell carcinoma; hypertrophic, rough lesions on perineum and perianal area.

Erosive (as in our case)—Glassy and brightly erythematous erosions with white striae or a white border (Wickham’s striae); architectural destruction with loss of the labia minora and clitoris and narrowing of the introitus. The epithelium is denuded leading to contact bleeding, discharge and vaginal adhesions. Care must be taken when obtaining biopsies; this is because if only areas of erosion are sampled, features associated with lichen planus will not be found, but instead those of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis—acute and chronic inflammation involving the mucosa and submucosa.5

Histological features of lichen planus are irregular acanthosis of the epidermis, liquefactive degeneration of the basal cell layer, and band-like dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes in the upper epidermis. The epithelium may be absent with areas of hyperkeratosis.6

Treatment of lichen sclerosis is based on anecdotal reports and small case series, the largest involving only 65 patients. Prevention of vaginal stenosis resulting in loss of sexual function is often the most challenging aspect of care. The use of Colifoam enemas intravaginally has not previously been reported. General principles in a multidisciplinary clinic include explanation of the chronicity of the disease with provision of support and education.

Sedating antihistamines used at night prevent scratching, and emollients reduce friction. Local anaesthetic gel, simple analgesia or low dose tricyclic antidepressants or anticonvulsants may ease discomfort. Superimposed infections should be treated promptly and any drugs associated with lichenoid reaction discontinued.

Ultrapotent topical steroids in a tapering dose are the treatment with the best evidence of efficacy.6,8 Enemas used intravaginally are an effective, patient friendly and widely available formulation. Flares or resistant disease may require oral steroids. Other treatments include cyclosporins, griseofulvin, dapsone, retinoids, hydroxychloroquine, and minocycline. The irritant properties of retinoids mean they cannot be used on eroded epithelium.7 Topical tacrolimus was shown to be more effective than topical steroids in two case series,8,9 but symptoms return on stopping treatment and side effects are more frequent and severe. Long term safety (>1 year) is unknown.

Surgery may be needed to breakdown vaginal adhesions and restore sexual function.10 Potent topical steroids and vaginal dilators must be used postoperatively to help prevent restenosis. Dedicated nursing support improves compliance and efficacy.

The risk of lichen planus leading to malignancy is unknown. Of 61 cases of squamous cell vulval carcinoma, three were found to have coexisting lichen planus.1 It is thought that longstanding inflammation may facilitate a neoplastic cellular clone to develop in epithelium undergoing continuous renewal. Long-term follow-up is necessary to monitor disease activity with a low threshold for repeat biopsies.

This case highlights that a combination of treatments provided in a multidisciplinary setting can result in a successful outcome for this challenging condition with high patient morbidity.

Learning points

Lichen planus is an uncommon multisystem disease that can present to a variety of specialities.

Always ask patients with lichen planus if they have any genital symptoms.

Biopsy is needed to exclude malignancy or vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia.

Vaginal stenosis with loss of sexual function is a challenging aspect of care.

Surgery followed by use of intravaginal Colifoam enemas and vaginal dilators is an effective treatment regimen.

Treatment in a combined clinic often improves patient satisfaction and outcome.

Acknowledgments

D Braid RN, of the Gynaecology Skin Clinic at Wellington Hospital, Capital & Coast DHB, Adelaide Road, Newtown, Wellington South, New Zealand for her help and advice. Dr A Oakley, Clinical Director, Department of Dermatology, Waikato Hospital, Private Bag 3200, Hamilton, New Zealand, for kindly supplying the images in fig 1.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lotery HE, Galask RP. Erosive lichen planus of the vulva & vagina. Obstet Gynecol 2003; 101: 1121–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis FM. Vulval lichen planus. Br J Dermatol 1998; 138: 569–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shiohara T. The lichenoid tissue reaction. An immunological perspective. Am J Dermatopathol 1988; 10: 252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis FM, Shah M, Harrington CI. Vulval involvement in lichen planus: a study of 37 women. Br J Dermatol 1996; 135: 89–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soper D, Patterson JW, Hurt WG, et al. Lichen planus of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol 1988; 72: 74–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson M, Kutzner S, Kaufman TH. Treatment of vulvovaginal lichen planus with vaginal hydrocortisone suppositories. Obstet Gynecol 2002; 110: 359–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards L. Vulval lichen planus. Arch Dermatol 1989; 125: 1677–80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrd J, Davis MDP, Rogers RS. Recalcitrant symptomatic vulval lichen planus. Arch Dermatol 2004; 140: 715–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen JT, Bird M, LeClair CM. Patient Satisfaction after the treatment of vulvovaginal erosive lichen planus with topical clobetasol and tacrolimus: a survey study. Am J Obstet Gynaecol 2004; 190: 1759–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stalburg CM, Haefner HK. Vaginal stenosis in lichen planus. Surgical treatment tips for patients in whom conservative therapies have failed. J Pelvic Med Surg 2008; 14: 193–8 [Google Scholar]