Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the clinical and radiological outcomes of lumbar interbody fusion and its correlation with various factors (e.g., age, comorbidities, fusion level, bone quality) in patients over and under 65 years of age who underwent lumbar fusion surgery for degenerative lumbar disease.

Methods

One-hundred-thirty-three patients with lumbar degenerative disease underwent lumbar fusion surgery between June 2006 and June 2007 and were followed for more than one year. Forty-eight (36.1%) were older than 65 years of age (group A) and 85 (63.9%) were under 65 years of age (group B). Diagnosis, comorbidities, length of hospital stay, and perioperative complications were recorded. The analysis of clinical outcomes was based on the visual analogue scale (VAS). Radiological results were evaluated using plain radiographs. Clinical outcomes, radiological outcomes, length of hospital stay, and complication rates were analyzed in relation to lumbar fusion level, the number of comorbidities, bone mineral density (BMD), and age.

Results

The mean age of the patients was 61.2 years (range, 33-86 years) and the mean BMD was -2.2 (range, -4.8 to -2.8). The mean length of hospital stay was 15.0 days (range, 5-60 days) and the mean follow-up was 23.0 months (range, 18-30 months). Eighty-five (64.0%) patients had more than one preoperative comorbidities. Perioperative complications occurred in 27 of 133 patients (20.3%). The incidence of overall complication was 22.9% in group A, and 18.8% in group B but there was no statistical difference between the two groups. The mean VAS scores for the back and leg were significantly decreased in both groups (p < 0.05), and bony fusion was achieved in 125 of 133 patients (94.0%). There was no significant difference in bony union rates between groups A and B (91.7% in group A vs. 95.3% in group B, p = 0.398). In group A, perioperative complications were more common with the increase in fusion level (p = 0.027). Perioperative complications in both groups A (p = 0.035) and B (p = 0.044) increased with an increasing number of comorbidities.

Conclusion

Elderly patients with comorbidities are at a high risk for complications and adverse outcomes after lumbar spine surgery. In our study, clinical outcomes, fusion rates, and perioperative complication rates in older patients were comparable with those in younger populations. The number of comorbidities and the extent of fusion level were significant factors in predicting the occurrence of postoperative complications. However, proper perioperative general supportive care with a thorough fusion strategy during the operation could improve the overall postoperative outcomes in lumbar fusion surgery for elderly patients.

Keywords: Elderly patients, Lumbar interbody fusion, Comorbidities, Complications

INTRODUCTION

As the size of the geriatric population increases, the number of elderly patients presenting with painful degenerative disease of the lumbar spine requiring surgery is expected to rise concomitantly. Many patients require posterior arthrodesis with instrumentation along with decompression to treat the degenerative lumbar disease. In the case of surgical treatment in these patients, it is important to consider surgical complications and outcomes in this population. These patients may be at increased risk for complications because of their age and associated medical conditions. Adverse patient age is often a major factor in deciding the extent of surgery to be performed, secondary to the perceived increased morbidity of performing more extensive surgery in the older patient population19).

However, there is a lack of studies addressing the perioperative complications occurring in elderly patients undergoing both decompression and arthrodesis of the lumbar spine and also the surgical results of posterior lumbar interbody fusion in elderly patients14). A review of some of the literature reveals controversy over the safety of lumbar laminectomy with or without fusion in the elderly, and there is disagreement over the risks of surgery in the population. Other studies raised concerns over increased morbidity in this population, cautioning against spinal surgery in the elderly4,10,11,15). Most of these studies merely report the overall complication rate and ignore the interaction between age and comorbidities.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate clinical and radiological outcomes and their correlation with perioperative complications and general factors (age, comorbidities, fusion levels, and bone mineral density) in patients over 65 years of age who underwent lumbar fusion surgery for degenerative lumbar disease. There is also a comparison with the results for patients under 65 years old.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients population

From June 2006 to June 2007, 214 patients underwent a lumbar interbody fusion procedure for the treatment of degenerative disease of the spine at Kyung-Hee University East-West Neo Hospital Spine Center. Among the 214 patients, we only included lumbar stenosis, spondylolisthesis, and herniated nucleus pulposus (HNP) patients treated with posterior lumbar interbody fusion combined with pedicle screw fixation. We excluded all patients who had a neoplasm, infectious disease, trauma, or deformity; those with a previous decompression and arthrodesis; and those who had a follow-up period of less than 1 year. Of the 133 patients who met our inclusion criteria, 48 (36.1%) were older than 65 years of age (group A) and 85 (63.9%) were under 65 years of age (group B). The records of these 133 patients were reviewed to determine demographic data, primary diagnosis, length of hospital stay, preoperative comorbidities, number of fused levels, and postoperative complications.

Operative technique

After induction of general anesthesia, patients underwent surgery in the prone position on a Jackson spinal table with the hips maximally extended. All patients had a standard midline lumbar posterior incision. A subperiosteal dissection of the paraspinal muscles was completed to the transverse process. Pedicle screws (Moss Miami, DePuy Spine, or Optima spinal system, U & I Corp.) were inserted under C-arm X-ray guidance before decompression to minimize blood loss and achieve distraction. Bilateral laminectomy and facetectomy using standard transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) techniques described elsewhere were performed at the level of the spinal segment to be fused. In the case of severe foraminal stenosis or spondylolisthesis, a Gill laminectomy with bilateral nerve root decompression was performed. The disk space was entered either unilaterally or bilaterally but we prefer bilateral cage insertion to decompression except for definite unilateral stenosis or anomalies, such as conjoined nerve root. After nearly completing the discectomy and the end plate preparation was done, bone from the facetectomy and mixed with the allograft (Hansol Medical Corp.) was inserted into the anterior part of the disk space for the enhancement of fusion. Then bilateral lumbar interbody cages (Brantigan CFRP I/F cage, DePuy Acromed) packed with facetectomy bone with allograft were inserted. Postoperative management included early mobilization on the second postoperative day with the aid of lumbar orthoses, which were used until around 3 months after surgery.

Assessment of clinical outcomes

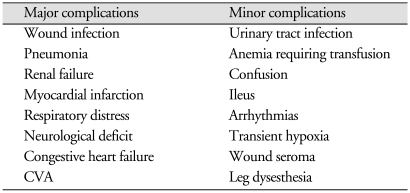

The comorbidities were classified as cardiac, pulmonary, urologic, gastrointestinal, endocrinologic, hepatobiliary, or miscellaneous. We used the classification of complications described by Carreon et al.4), which were categorized as major or minor. A complication adversely affecting the patient's recovery was considered a major complication. A complication noted in the medical records but that did not alter the patient's recovery was considered a minor complication (Table 1). The clinical results were evaluated according to the visual analogue scale (VAS) score for back and leg. The scores were calculated before surgery, at 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year after the surgery, and at the final follow-up visit.

Table 1.

Categorization of major and minor complications

CVA : cerebrovascular accident

Evaluation of successful bone fusion

The lumbar interbody bone fusion was evaluated by plain radiographs using the Kuslich method13). This is the presence of bridging bones between vertebral bodies, either within or external to the cage, and 5° or less of measured motion on flexion-extension radiographs. Any movement detected between the vertebral bodies, lucency observed within the cage, or at the cage-bone interface on the dynamic view were considered signs of nonunion.

Statistical analysis

Logistic regression analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 12.0, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) to compare whether age, number of comorbidities, increasing fusion level, bone mineral density (BMD), or other factors were associated with clinical and radiological outcomes.

RESULTS

Patients characteristics

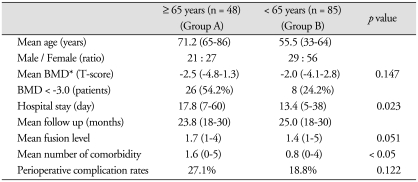

A total of 133 patients underwent lumbar interbody fusion. The mean age of the patients was 61.2 years (range, 33-86 years), the male/female ratio was 50 : 83. The mean BMD was -2.2 (range, -4.8-2.8). The mean hospital stay was 15.0 days (range, 5-60 days). The mean follow up day was 23.0 months (range, 18-30 months). The preoperative diagnoses were lumbar stenosis 54.2%, spondylolisthesis 43.8% , HNP 2.0% in group A, whereas 31.8%, 63.5%, 4.7% in group B. Patients demographics between age older than 65 years (group A) and age under 65 years (group B) are summarized in Table 2 and there was a statistically significant difference in hospital stay (p = 0.023) and the mean number of comorbidity (p < 0.05) between two groups.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients data between group A and B

BMD : bone mineral density

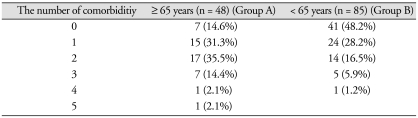

Clinical outcomes

Eighty-five patients (64.0%) had more than one preoperative comorbidity requiring medical intervention. The most common comorbidity was a cardiac problem, such as hypertensive disorder (37.3%). Table 3 summarizes the number of comorbidities in groups A and B.

Table 3.

The number of comorbidities in group A and B

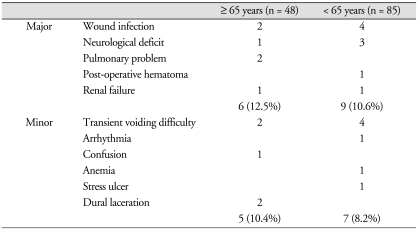

Perioperative complications occurred in 27 of 133 patients (20.3%). Fifteen patients had a major complication (11.3%), 12 patients had a minor complication (9.0%), and no patients had more than one complication.

The incidence of overall complication was 22.9% in group A and 18.8% in group B; there was no statistical difference between the two groups (p = 0.472). The incidence of major and minor complications between the two groups also showed no statistical difference (Table 4).

Table 4.

Major and minor complications between group A and B

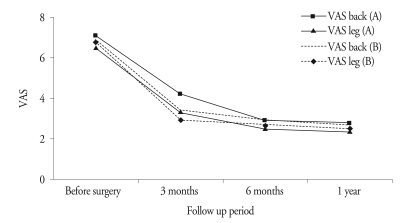

Wound infection was the most common major complication. All infections were treated with conservative intravenous antibiotics, except one case, which was treated with a wound incision and debridement. The most common minor complication was a transient voiding difficulty. The mean VAS scores for the back significantly decreased from preoperative (7.1 ± 1.3) to final follow-up (2.8 ± 1.2) in group A, and from 6.9 ± 2.1 to 2.6 ± 1.6 in group B. The VAS for the leg decreased from 6.5 ± 1.6 to 2.3 ± 1.1 in group A, and from 6.8 ± 2.0 to 2.5 ± 1.3 in group B, and there was no significant difference between the two groups (p < 0.05). Fig. 1 details the changes in VAS scores from preoperative to final follow-up between the two groups.

Fig. 1.

The serial change of VAS score in group A and B during follow period.

During the follow-up period, two patients (one patient in each group) had additional surgery caused by the development of an adjacent segment disease. No patients died in the hospital or during the follow-up period.

Radiological outcomes

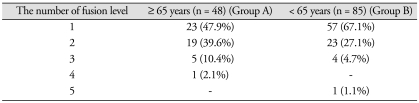

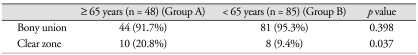

The average fusion level of 133 patients was 1.5 (range, 1-5 levels) and the extent of fusion level between the two groups is summarized in Table 5. Bony fusion was achieved in 125 of 133 patients (94.0%). Bone fusion rates in the older age group were a little lower than in the younger group but there was no statistically significant difference in bone union rates between the groups (91.7% in group A vs. 95.3% in group B, p = 0.398), except in the clear zone, meaning the periscrew halo sign showed a significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.037) (Table 6).

Table 5.

Fusion level of patient between group A and B

Table 6.

The radiological results of patient between group A and B

Multi factor analysis

We also analyzed whether increasing fusion level and the number of comorbidities correlated with radiological outcomes, VAS score, length of hospital stay, and perioperative complications in each group. In group A, when the fusion level increased, there was a corresponding increase in perioperative complications (p = 0.027); conversely, radiological outcomes, improvement of VAS score, and hospital stay did not correlate with increased fusion levels. In group B, there was no statistically significant correlation between any factors as the fusion level increased. As the number of comorbidities increased, the perioperative complications in both groups A (p = 0.035) and B (p = 0.044) also increased. This also showed that the length of the hospital stay increased as the number of comorbidities increased in group A (p < 0.01). However, the other factors did not show any statistically significant correlation. Of the 81 patients who had a BMD examination, we redistributed the patient data for the two groups. One group was 31 patients whose BMD score was lower than -3.0, and the other group was 50 patients with a score higher than -3.0. We analyzed the outcome differences between these two groups, and a decreased BMD did not correlate with an improvement in the VAS score, duration of hospital stay, or incidence of perioperative complications. Only radiological outcomes (bone fusion rates) showed a meaningful difference (p = 0.064), although it did not reach statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

As the size of the elderly population increases, so does the number of elderly patients undergoing posterior decompression and fusion for a variety of degenerative lumbar disorders6,8). Sometimes the surgical treatment of older patients is controversial. Due to the consequences of aging, a routine surgical procedure can become more complicated and perioperative complications might increase. However, for patients for whom nonoperative measures have failed, surgery may be the only remaining option to relieve their pain3). Hence, both the risks and the benefits of each aspect of a surgical procedure need to be carefully weighed, particularly in the older patient population, which often has a more complex set of issues that can adversely affect outcome4).

Many previous studies have attempted to quantify complication rates in older patients undergoing various lumbar spinal procedures6,8,15), but there is no consensus as to type or frequency with which these complications occur or which risk factors may predispose an elderly person to their development.

Deyo et al.7) noted higher rates of morbidity and mortality during hospitalization with increased patient age. Ciol et al.6) reported similar findings. Oldridge et al.15) reported increased mortality only in patients over the age of 80. Ragab et al.17), however, reported the results of 118 patients over the age of 70 who underwent decompressive lumbar surgery for a variety of pathologies at their institution during an earlier time period, and found that advanced age did not increase the associated morbidity and mortality. In our study, no patients died during the admission or follow-up period so we could not investigate the mortality of patients. However, the increased age (older than 65 years old) of patients was associated with more comorbidities and a longer hospital stay. As for complication rate, it was somewhat higher in group A (22.9%) than in group B (18.8%), but there was no significant difference in the incidence of complication rate according to age groups in our series (p = 0.472).

There are few data on perioperative complication rates in older age groups after posterior lumbar decompression and arthrodesis. Most studies report on small numbers of poorly matched patients. Benz et al.2) reported on 68 patients over the age of 70 who underwent decompressive lumbar surgery, but only 41 underwent concomitant arthrodesis (14 with instrumentation). They reported a 41% overall complication rate and a 12% rate of serious complications. In the study by Ragab et al.17), only 45 of the 118 elderly patients underwent arthrodesis after decompression (three with instrumentation). Their overall complication rate was 20%, which included both intraoperative and postoperative complications in patients undergoing decompression with or without arthrodesis.

Raffo and Lauerman16) recently reported on 20 patients in their ninth decade who had undergone lumbar decompression and fusion for lumbar spinal stenosis associated with instability. They noted a 20% rate of major complications and found that comorbidities correlated with their occurrence. Carreon et al.4) specifically evaluated the rate of perioperative complications in elderly patients undergoing arthrodesis. They retrospectively reviewed 98 patients aged 65 or older who had undergone posterior decompression and fusion with supplemental instrumentation. They reported that at least one major complication occurred in 21% of patients (30 major complications in 21 patients), and at least one minor complication occurred in 70% of patients (128 minor complications in 69 patients). They included blood transfusion as a minor complication (26 patients). They found that older age and an increased number of levels fused were found to be risk factors for the development of a major complication, but the presence or the number of comorbidities did not correlate with the occurrence of complications.

In our findings, the overall complication rate for 133 patients was 20.3%, with a major complication rate of 11.3% and a minor complication rate of 9.0%. In group A, the total complication rate was 22.9%; 12.5% of patients developed a major complication and 10.4% a minor complication. The overall complication rates were somewhat similar to a previous study by Ragab et al.17) but the major complication rate was a little lower than Raffo and Lauerman16) and Carreon et al.4), whose studies lacked comparison with younger groups. Comparing the complication rates between groups A and B in our series of studies, the mean, major, and minor complication rates showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups. However, the results of the multi-factor analysis showed that an increased number of medical comorbidities or fusion level had an effect on the occurrence of complications in group A (p < 0.05) and that age showed no statistical difference (p = 0.122). This is somewhat different from the results of Carreon et al.4).

While some have found the presence or number of comorbidities to increase the complication rate6,9,18), others have not found this to be the case2,4,17).

Chronic disease has been shown to impact mortality dramatically. Oldridge et al.15) reported the relative risk of inpatient mortality, adjusted for age and sex and compared with zero comorbidities, to be 4.79 for one comorbidity, 12.50 for two comorbidities, and 21.59 for three comorbidities. These trends were maintained to a lesser extent for 30-day and 1-year mortality.

Several other studies of surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis have noted that comorbidity is associated with worse symptoms, function, and satisfaction1,10,12). Katz et al.10) found that greater cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, and overall comorbidity led to inferior scores in most of the outcome measurements in older patients who underwent lumbar surgery.

In our study, an increased number of comorbidities was closely related with increasing perioperative complications in both groups A (p = 0.035) and B (p = 0.044).

Regardless of the fact that arthrodesis increases the complication rate significantly over decompression alone, many older patients have concomitant degenerative diagnoses that mandate fusion. However, long level fusion is associated with a significantly high complication rate in patients older than 70 years4). Cassinelli et al.5) reported that fusion procedures had a staggering mortality rate, more than 10% in Medicare beneficiaries aged 80-85 years. In addition, in our studies, as fusion level increased, perioperative complication increased, especially in group A (p = 0.027), but the younger patients in group B showed no statistical difference. In a study of 101 patients who had posterior lumbar interbody fusion in which 31 patients were more than 70 years old, and comparing them with the results of 70 patients younger than 70 years old, and despite the age difference in the two groups, Okuda et al.14) reported no obvious difference in the clinical and fusion results. They also reported no nonunion in either group. Other studies did not mention the fusion rates of older age patients. In our review, the overall fusion rates were 94.0% and 91.7% in group A and 95.3% in group B. Fusion rates showed no statistical difference according to patient age (p = 0.398), although the fusion rates of the younger age group were a little higher than those of the older patients, and the rates of the clear zone were significantly lower than the older age group (p = 0.037). These results may be due to the poorer bony quality of older patients, but when we analyzed the fusion rate by means of BMD, this showed no statistically significant difference associated with bone quality, only a meaningful distinction (p = 0.064).

Although several studies have described the technique for lumbar interbody fusion, we are convinced that preparation of the fine-bone graft area and the use of a large amount of bone graft are of critical importance for the success of fusion, even in older patients with poorer bone quality.

The limitations of our study are a small number of patients, its retrospective design, lack of clinical data about the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classes, estimated blood loss, and operation time. Evaluation of clinical outcome parameters is also confined to the VAS score. If we could add surveys, such as the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) and a self-administered questionnaire, they would be helpful in following overall patient clinical outcomes, including daily activities and satisfaction with the surgery.

CONCLUSION

Our study found that clinical outcomes, radiological outcomes and perioperative complication rates in older patients had lumbar interbody fusion with pedicle screw fixation for degenerative lumbar disease are comparable with those younger populations.

However, surgeon should consider a longer hospital stay, a higher number of associated comorbidities, and the poorer bone quality of elderly patients and should take into account when the fusion level and comorbidities increase, an increase in perioperative complication rates could also occur. Nevertheless age should not be used as a absolute criterion to avoid decompression and fusion for the treatment of lumbar degenerative disease in elderly patients. With the aid of carefully control of preoperative risk factors and skillful surgical technique, patients with comobidity and age exceeding 65 years can undergo lumbar spine interbody fusion surgery and experience outcomes relatively similar to those for a younger population.

References

- 1.Airaksinen O, Herno A, Turunen V, Saari T, Suomlainen O. Surgical outcome of 438 patients treated surgically for lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997;22:2278–2282. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199710010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benz RJ, Ibrahim ZG, Afshar P, Garfin SR. Predicting complications in elderly patients undergoing lumbar decompression. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001:116–121. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200103000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Best NM, Sasso RC. Outpatient lumbar spine decompression in 233 patients 65 years of age or older. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:1135–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000261486.51019.4a. discussion 1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carreon LY, Puno RM, Dimar JR, 2nd, Glassman SD, Johnson JR. Perioperative complications of posterior lumbar decompression and arthrodesis in older adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:2089–2092. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200311000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cassinelli EH, Eubanks J, Vogt M, Furey C, Yoo J, Bohlman HH. Risk factors for the development of perioperative complications in elderly patients undergoing lumbar decompression and arthrodesis for spinal stenosis : an analysis of 166 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:230–235. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000251918.19508.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciol MA, Deyo RA, Howell E, Kreif S. An assessment of surgery for spinal stenosis : time trends, geographic variations, complications, and reoperations. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:285–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Loeser JD, Bigos SJ, Ciol MA. Morbidity and mortality in association with operations on the lumbar spine. The influence of age, diagnosis, and procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:536–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deyo RA, Gray DT, Kreuter W, Mirza S, Martin BI. United States trends in lumbar fusion surgery for degenerative conditions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:1441–1445. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000166503.37969.8a. discussion 1446-1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glassman SD, Alegre G, Carreon L, Dimar JR, Johnson JR. Perioperative complications of lumbar instrumentation and fusion in patients with diabetes mellitus. Spine J. 2003;3:496–501. doi: 10.1016/s1529-9430(03)00426-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz JN, Lipson SJ, Brick GW, Grobler LJ, Weinstein JN, Fossel AH, et al. Clinical correlates of patient satisfaction after laminectomy for degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:1155–1160. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199505150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz JN, Lipson SJ, Larson MG, McInnes JM, Fossel AH, Liang MH. The outcome of decompressive laminectomy for degenerative lumbar stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:809–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katz JN, Stucki G, Lipson SJ, Fossel AH, Grobler LJ, Weinstein JN. Predictors of surgical outcome in degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999;24:2229–2233. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199911010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McAfee PC, Boden SD, Brantigan JW, Fraser RD, Kuslich SD, Oxland TR, et al. Symposium : a critical discrepancy-a criteria of successful arthrodesis following interbody spinal fusions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:320–334. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200102010-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okuda S, Oda T, Miyauchi A, Haku T, Yamamoto T, Iwasaki M. Surgical outcomes of posterior lumbar interbody fusion in elderly patients. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(Suppl 2 Pt.2):310–320. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oldridge NB, Yuan Z, Stoll JE, Rimm AR. Lumbar spine surgery and mortality among Medicare beneficiaries, 1986. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1292–1298. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.8.1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raffo CS, Lauerman WC. Predicting morbidity and mortality of lumbar spine arthrodesis in patients in their ninth decade. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:99–103. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000192678.25586.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ragab AA, Fye MA, Bohlman HH. Surgery of the lumbar spine for spinal stenosis in 118 patients 70 years of age or older. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28:348–353. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000048494.66599.DF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith EB, Hanigan WC. Surgical results and complications in elderly patients with benign lesions of the spinal canal. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:867–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tadokoro K, Miyamoto H, Sumi M, Shimomura T. The prognosis of conservative treatments for lumbar spinal stenosis : analysis of patients over 70 years of age. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:2458–2463. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000184692.71897.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]