Abstract

Proliferating cells, including cancer cells, require altered metabolism to efficiently incorporate nutrients such as glucose into biomass. The M2 isoform of pyruvate kinase (PKM2) promotes the metabolism of glucose by aerobic glycolysis and contributes to anabolic metabolism. Paradoxically, decreased pyruvate kinase enzyme activity accompanies the expression of PKM2 in rapidly dividing cancer cells and tissues. We demonstrate that phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), the substrate for pyruvate kinase in cells, can act as a phosphate donor in mammalian cells as PEP participates in the phosphorylation of the glycolytic enzyme phosphoglycerate mutase (PGAM1) in PKM2 expressing cells. We used mass spectrometry to show that the phosphate from PEP is transferred to the catalytic histidine (His-11) on human PGAM1. This reaction occurred at physiological concentrations of PEP and produced pyruvate in the absence of PKM2 activity. The presence of histidine-phosphorylated PGAM1 correlated with the expression PKM2 in cancer cell lines and tumor tissues. Thus, decreased pyruvate kinase activity in PKM2-expressing cells allows PEP-dependent histidine phosphorylation of PGAM1, and may provide an alternate glycolytic pathway that decouples ATP production from PEP-mediated phosphotransfer, allowing for the high rate of glycolysis to support anabolic metabolism observed in many proliferating cells.

Introduction

One of the major differences observed between cancer cells and normal cells is in how they metabolize glucose; most cancer cells primarily metabolize glucose by glycolysis whereas most normal cells completely catabolize glucose by oxidative phosphorylation (1). This shift to aerobic glycolysis with lactate production (also known as the Warburg effect), coupled with increased glucose uptake is likely used by proliferating cells to promote the efficient conversion of glucose into the macromolecules needed to construct a new cell (2). The glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase is alternatively spliced to produce either the M1 (PKM1) or M2 (PKM2) isoforms (3). The splice-isoform of pyruvate kinase expressed in cells influences the extent to which glucose is metabolized by either aerobic glycolysis or oxidative phosphorylation. Cells expressing PKM2 produce more lactate and consume less oxygen than cells expressing PKM1 (4). Consistent with this metabolic phenotype, all cancer cells studied to date exclusively express PKM2 whereas cells in many normal differentiated tissues express PKM1. PKM2 differs from PKM1 in that its activity can be negatively regulated in response to growth factor signaling by binding to tyrosine phosphorylated proteins (5, 6). Paradoxically, it is this ability to interact with tyrosine phosphorylated proteins, and decrease pyruvate kinase activity, that appears to be important for cell proliferation (5). This selection for the decreased activity of a rate-limiting glycolytic enzyme appears inconsistent with the increased glucose utilization that is characteristic of cancer cells. However, complete catabolism of pyruvate to CO2 may be counterproductive in a dividing cell as it may limit the availability of precursors and reducing potential necessary to produce biomass.

PKM2 is less active than PKM1 in vitro and in cells

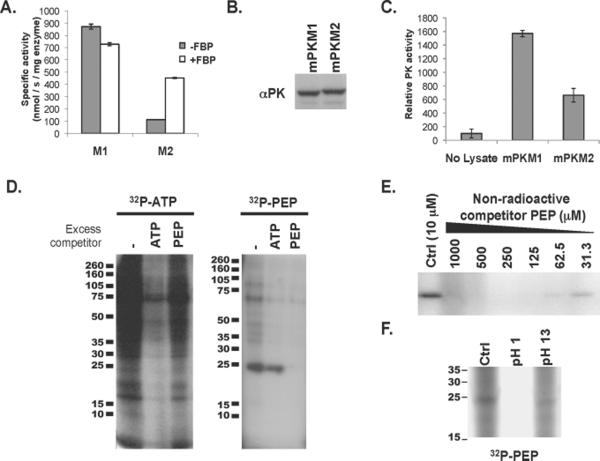

We directly compared the specific activity of PKM1 and PKM2 both in vitro and in cell lysates. Recombinant PKM1 enzyme had a high specific activity that was independent of the PKM2-specific allosteric activator FBP (Fig. 1A) (7). The specific activity of PKM2 that is fully activated by FBP is approximately half that of PKM1. The property of PKM2 that appears to promote cell proliferation in vivo is it's interaction with tyrosine phosphorylated proteins and consequent release of FBP. In the absence of FBP, PKM2 had less than one quarter of the activity of PKM1 (Fig. 1A). To determine if the differences in activity observed with recombinant enzymes are also seen in cells, we measured pyruvate kinase activity in lysates from cells engineered to express equivalent amounts of either PKM1 or PKM2 in the absence of the other isoform (Fig. 1B). Under these identical conditions, PKM2 expression provides a selective advantage for growth in vivo (4). Lysates from PKM2-expressing cells exhibited less than half the pyruvate kinase activity of lysates from cells expressing the equivalent amount of PKM1 (Fig. 1C). Thus, the selection for PKM2-expression in proliferating cells is accompanied by a decrease in total cellular pyruvate kinase activity.

Fig. 1. Evidence of PEP-dependent phosphorylation of a 25-kD protein in PKM2 expressing cells with less pyruvate kinase activity.

A. 6xHis-tagged human PKM1 and PKM2 were expressed in E. coli and purified by Ni-affinity chromatography. The specific activity of each enzyme was determined in the presence of saturating amounts of PEP and ADP. The activity of PKM1 and PKM2 in the presence and absence of FBP is shown.

B. H1299 cells were engineered to express equivalent amount of PKM1 or PKM2 protein as described previously (4). Equivalent expression of PKM1 and PKM2 was confirmed by Western blot using an antibody (αPK) that recognizes an epitope shared by PKM1 and PKM2 as shown.

C. As in (A), pyruvate kinase activity was determined using saturating amounts of PEP and ADP. The relative pyruvate kinase activity observed in the PKM1- or PKM2-expressing cells described in (B), relative to lysis buffer alone, is shown.

D. HEK293 cells were hypotonically lysed and incubated with 32P-labeled ATP or 32P-labeled PEP prior to analysis by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The lysates were incubated with 32P-labeled ATP or 32P-labeled PEP in the presence of 10 μM ATP or PEP respectively (−), or with the addition of 1 mM non-radioactive competitor ATP or PEP as shown.

E. Cell lysate was incubated with 32P-labeled PEP in the presence of the indicated concentration of non-radioactive competitor PEP prior to analysis by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography as shown.

F. Cell lysate was incubated with 32P-labeled PEP as above and the pH of the reaction was changed to pH 1 or pH 13 as indicated. Reactions were incubated for 2 hours at 65° C prior to analysis by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography as shown.

Donation of phosphate from phosphoenolpyruvate to a cytosolic protein of about 25-kD

It is possible that the relative decrease in PKM2 activity allows an upstream metabolite in glycolysis to signal energy status or to be shunted to an undiscovered, or underappreciated, metabolic pathway required for cell division. The substrate for pyruvate kinase in cells is phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP). Bacteria use PEP as the initial phosphate donor for protein phosphorylation in a signaling cascade that regulates carbohydrate metabolism in response to nutrient availability (8, 9). In addition, transfer of the PEP phosphate to a protein occurs as an enzymatic intermediate within the Calvin cycle of C4 plants (10, 11). This prompted us to explore the possibility that PEP might transfer its phosphate to a protein in mammalian cells. We generated 32P-labeled PEP (Fig. S1) and tested hypotonic lysates from human embryonic kidney cells for the presence of such a PEP-dependent protein phosphorylation activity. Incubation of extracts with γ-32P- ATP resulted in numerous 32P-labeled proteins and the 32P-labeling of these proteins was abolished after addition of a 100-fold excess amount of non-radioactive ATP (Fig. 1D). No decrease incorporation of phosphate from γ-32P- ATP was observed in the presence of excess non-radioactive PEP. However, incubation of cell extracts with 32P-labeled PEP resulted in the incorporation of 32P into several proteins, the most prominent of which resolved at a relative molecular size of approximately 25-kD by SDS-PAGE. The 32P-labeling of this protein was eliminated after addition of excess amounts of non-radioactive PEP but not by excess non-radioactive ATP, consistent with PEP acting as the phosphate donor (Fig. 1D). Other purine nucleotides, including GTP, did not compete with 32P-labeled PEP to phosphorylate the 25-kDa protein, and phosphorylation of a 25-kD protein was observed in extracts from multiple cell lines incubated with 32P-labeled PEP (Fig. S2). Cytoplasmic concentrations of PEP are less than 30 μM in eukaryotic cells (12, 13). To determine if phosphorylation of this protein is possible at low μM concentrations of PEP, we added increasing concentrations of non-radioactive PEP to estimate the Km for PEP in the reaction (Fig. 1E). Increasing the amount of un-labeled PEP above 10 μM resulted in decreased 32P-labeling of the 25-kD protein, suggesting that the Km for PEP involved in this reaction is in a range where this reaction could occur at concentrations of PEP present in cells.

PEP-dependent phosphorylation of the 25-kD protein on histidine

The phosphorylation reaction involving PEP in bacterial two-component signaling and the analogous PEP-dependent protein phosphorylation as an enzymatic intermediate in C4 plants both involve transfer of the PEP phosphate to a histidine residue. O-linked protein phosphates such as those seen upon phosphorylation of serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues are stable under acidic conditions (14, 15). In contrast, N-linked protein phosphates such as phospholysine or phosphohistidine are labile at low pH, but stable under basic conditions. Therefore, we exposed protein extracts that had been incubated with 32P-labeled PEP to acidic or basic conditions before analysis by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The 32P signal was lost after incubation at pH 1 but retained at pH 13 (Fig. 1F), which is consistent with an N-linked phosphate resulting from PEP-dependent phosphorylation of the 25-kD protein. Incubation of 32P-ATP labeled lysates at pH 1 resulted in no loss of protein phosphorylation indicating that loss of signal from the PEP-phosphorylated protein at low pH was not the result of non-specific acid hydrolysis. Consistent with an N-linked phosphorylation, in `standard` phosphoaminoacid analysis involving acid hydrolysis of the 25-kD PEP-phosphorylated protein, all of the resulting radioactivity migrated as inorganic phosphate (Pi) on thin layer electrophoresis (Fig. S3A). During reverse phase thin layer chromatography after base hydrolysis, the 32P migrated with phosphohistidine, consistent with histidine as the target of PEP-dependent phosphotransfer (Fig. S3B).

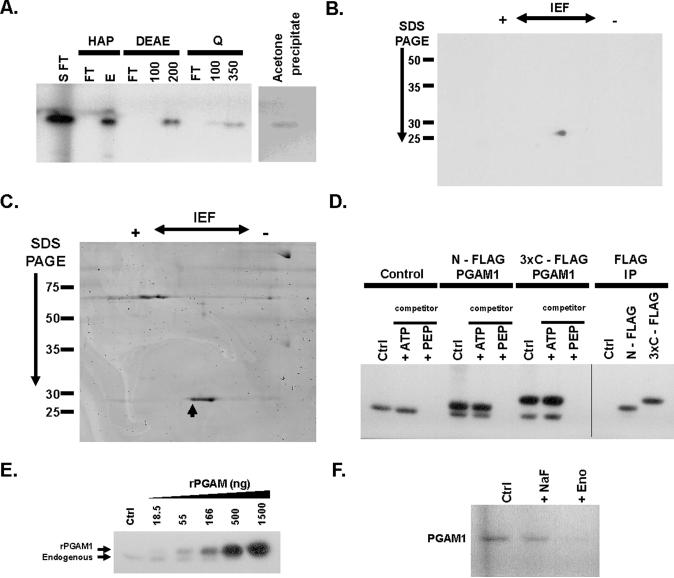

Identification of the 25-kD PEP-phosphorylated protein as phosphoglycerate mutase

The PEP-utilizing phosphorylating activity and the 25-kD target of phosphorylation were present in the S100 cytosolic fraction of HEK293 cells, and were retained in the flow-through fractions of both a strong cation exchange column and a C11NP column, which contained a resin we synthesized as a possible PEP affinity column. We fractionated the previously phosphorylated 25-kD target by both anion exchange and hydroxyapatite chromatography using salt elution but were unable to detect phosphorylation activity within any of the fractions from these columns upon their incubation with 32P-labeled PEP. This is consistent with the presence of an enzymatic transfer of phosphate from PEP to a protein, and a separation of the 25-kD target protein from an activity required for the observed phosphorylation. We purified the target protein by collecting the flow through fractions from an S100 protein extract passed sequentially through a C11NP column and a strong cation exchange (S) column. 32P-labeled PEP was added to this partially fractionated lysate to label the 25-kD protein, and the resulting 32P-labeled protein was then sequentially fractionated over three columns to effect the maximal recovery of the target protein (Fig. 2A). The proteins in the fraction from the strong anion exchange (Q) column containing the 32P-labeled 25-kD protein were precipitated with acetone and subjected to 2D electrophoresis (Fig. 2, A and B; Fig. S4). Analysis of the 2-dimensional sequential isoelectric focusing (IEF) and SDS-PAGE gel by autoradiography identified a single radioactive isoelectric species (pI = ~6.2) at 25-kD (Fig. 2B). The 32P-labeled spot corresponded to the most acidic coomassie-stained spot in a series of several adjacent isoelectric species at 25-kD on a coomassie stained gel (Fig. 2C). In-gel trypsin digestion followed by microcapillary tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) with protein database searching identified the 32P-labeled species as well as the adjacent species to be different isoelectric forms of the glycolytic enzyme phosphoglycerate mutase 1 (PGAM1) (Table S1).

Fig. 2. PGAM1 as the target of PEP-dependent phosphorylation through an enolase-independent reaction.

A. The S100 fraction from a HEK293 cell lysates was passed sequentially through a custom column and a strong cation exchange column prior to incubating with 32P-labeled PEP (S FT). This reaction was then applied to a hydroxyapatite (HAP) column and eluted with 50 mM NaHPO4. The salt elution (E) containing the 32P-labeled species was diluted to < 25 mM NaHPO4 and applied to a weak anion exchange (DEAE) column. Elution from the DEAE column was performed with 100 mM and 200 mM NaCl as indicated. The 200 mM salt fraction containing the 32P-labeled species was diluted to 50 mM NaCl and applied to a strong anion exchange (Q) column and eluted sequentially with 100 mM and 350 mM NaCl as indicated. The 350 mM salt fraction containing the 32P-labeled species was acetone precipitated for analysis by 2D-IEF/SDS-PAGE. An aliquot of each fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography as shown. Flow through fractions are indicated as (FT).

B. The acetone-precipitated 350 mM salt fraction described in (A) was separated by 2D-IEF and SDS-PAGE and the 32P-labeled species was identified by autoradiography as shown.

C. The acetone-precipitated 350 mM salt fraction prepared as described in (A) was separated by 2D-IEF and SDS-PAGE and proteins identified by coomassie stain as shown. The species corresponding to the 32P-labeled species is indicated with an arrow.

D. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with control plasmid (Control), a N-terminally FLAG tagged PGAM1 cDNA (N-FLAG PGAM1), or a C-terminal triple FLAG tagged PGAM1 cDNA (3×C – FLAG PGAM1) as indicated. Hypotonic lysates from these cells were incubated with 32P-labeled PEP alone (Ctrl) or in the presence of 1 mM cold competitor ATP or PEP as indicated. The products of these reactions were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography as shown. Protein immunoprecipitated with an antibody to FLAG from the reactions without non-radioactive competitor were also analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography as shown.

E. Recombinant 6xHis-tagged PGAM1 (rPGAM1) was produced in E. coli and purified by Ni-affinity chromatography. Increasing quantities rPGAM1 were incubated with 10 μg of HEK293 cell lysate and 32P-PEP as shown. The phosphorylation of both the endogenous PGAM1 present in the cell lysate and rPGAM1 was determined by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

F. Cell lysates were incubated with 32P-labeled PEP in the absence (Ctrl) or presence of NaF or exogenously added rabbit muscle enolase enzyme (Eno) as indicated. The labeling of PGAM1 was determined by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography as shown.

To confirm that PGAM1 was indeed the target of PEP phosphorylation, FLAG-tagged PGAM1 constructs were transiently transfected into HEK293 cells and lysates from these cells were incubated with 32P-labeled PEP. When the proteins in these reactions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography, a second 32P-labeled species of greater molecular weight corresponding to the size of the epitope tagged PGAM1 was observed (Fig. 2D, Fig. S5A). The larger species was removed and recovered by immunoprecipitation with an antibody to FLAG and its labeling with 32P was blocked with excess non-radioactive PEP but not with excess non-radioactive ATP (Fig. 2D). Thus, the 32P from 32P-labeled PEP can be transferred to PGAM1. To confirm that the 25-kD protein labeled from 32P-labeled PEP is also PGAM1, we incubated lysates from control- and epitope-tagged PGAM1-transfected cells with 32P-labeled PEP and subjected them to limited proteolysis. When analyzed by SDS-PAGE, both the control lysates and those containing FLAG-tagged PGAM1 produced identical patterns of 32P-labeled peptides after limited proteolysis (Fig. S5B). Finally, recombinant PGAM1 added with 32P-labeled PEP to a fixed amount of cell lysate could compete for phosphorylation of endogenous PGAM1 (Fig. 2E). These data demonstrate that PGAM1 can be phosphorylated by PEP.

PGAM1 phosphorylation is independent of enolase activity

Although recombinant PGAM1 can be phosphorylated by 32P-labeled PEP in cell lysates, purified recombinant PGAM1 is not a direct substrate (Fig. S5C), indicating that an enzymatic activity in cell lysates is required to catalyze PGAM1 phosphorylation by PEP. PGAM1 acts as an enzyme in glycolysis to interconvert 3-phosphoglycerate (3PG) and 2-phosphoglycerate (2PG) through a phosphohistidine intermediate (16). Because PEP can be converted by the glycolytic enzyme enolase into 2PG it seemed possible that the PEP-dependent phosphorylation of PGAM1 that we observed in cell lysates involved conversion of 32P-PEP into 32P-2PG by enolase, followed by transfer of the 32P-phosphate from 2PG to the catalytic histidine of PGAM1. We therefore increased enolase activity by addition of exogenous enolase enzyme, or decreased it by addition of the enolase inhibitor NaF (17) to cell lysates (Fig. S6). The inhibition of enolase activity with NaF had minimal effect on the transfer of 32P from PEP to PGAM1 (Fig. 2F). Furthermore, the addition of exogenous enolase prevented the transfer of 32P from PEP to PGAM1 presumably by converting 32P- PEP to 2PG. These data indicate that conversion of PEP to 2PG by enolase is not involved in the observed phosphotransfer from PEP to PGAM1.

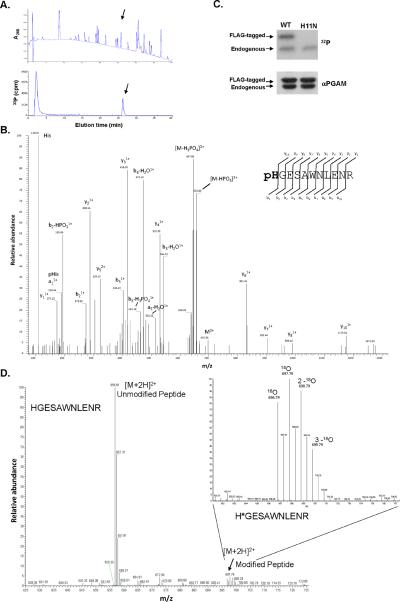

Phosphorylation of PGAM1 on the catalytic histidine (His-11) by the phosphate from PEP

To determine whether the phosphate from PEP was transferred to one or more sites on PGAM1, we labeled PGAM1 with 32P from PEP, digested the protein with trypsin, and analyzed the resulting peptides by 2 dimensional thin layer chromatography and thin layer electrophoresis followed by autoradiography (Fig. S7A). This revealed a single 32P-labeled species, indicating that only a single site is phosphorylated on PGAM1 in the reaction with PEP.

Phosphoaminoacid analysis indicated that PGAM1 was phosphorylated on a histidine residue (Fig. S3). To determine which histidine residue was phosphorylated, we incubated recombinant PGAM1 with 32P-labeled PEP and HEK293 cell lysate, and the 32P-labeled PGAM1 was recovered through association with Ni-agarose beads (Fig. S7B). This 32P-labeled PGAM1 was then digested with trypsin and the resulting peptides were separated by high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Fig. 3A). A single 32P-labeled peptide was observed. HPLC fractions were collected to confirm which peak contained the 32P-labeled peptide (Fig. S7, C and D), and the fraction containing the 32P-labeled peptide was sequenced by LC/MS/MS using a hybrid linear ion trap-orbitrap mass spectrometer with use of the higher energy collision dissociation cell (HCD) (18). HCD was required to clearly resolve the low mass fragment ions to show that the site of phosphorylation in the peptide sequence was localized to histidine 11 (H11) of PGAM1 (Fig. 3B, Fig. S8). Detection of histidine phosphorylation using mass spectrometry is challenging, but has previously been reported (19–22). The pHis site was confirmed using two different database search algorithms (Mascot and Sequest) with statistically significant scores. Consistent with H11 being the residue phosphorylated, mutation of H11 to asparagine abolished transfer of 32P from PEP to PGAM1 (Fig. 3C). To confirm that the phosphate at H11 is from exogenously added PEP rather than a phosphate that was present prior to cell lysis, we incubated recombinant PGAM1 with 18O-phosphate-labeled PEP (Fig. S9) in the presence of 1 mM normal isotopic ATP and HEK293 cell lysate, and then isolated PGAM1 with Ni-agarose beads, digested it with trypsin, and separated the peptides by HPLC. The peptide fraction containing H11 was analyzed by orbitrap mass spectrometry in FT-MS mode and several isotopic species were identified that corresponded to the H11 phosphorylated peptide (Fig. 3D). The heavy isotopic forms were consistent with 18O labeling of the phosphate that was transferred to the peptide from the 18O-labeled PEP rather than from the normal isotopic (16O) ATP. These data demonstrate that the phosphate group from PEP is transferred to H11 of PGAM1.

Fig. 3. Transfer of the phosphate of PEP to H11 of PGAM1.

A. Recombinant 6xHis-tagged PGAM1 (rPGAM1) was phosphorylated by 32P-PEP in a cell extract and recovered by binding to Ni-agarose beads. The 32P-labeled rPGAM was then digested with trypsin and the peptides separated using HPLC. A chromatograph identifying peptide peaks by absorbance at 208 nm and the presence of 32P determined by in-line scintillation counting is shown. The peptide peak eluting at ~ 26 minute containing 32P is delineated with an arrow.

B. The higher energy collision cell (HCD) MS/MS spectrum for the phosphorylated histidine containing peptide pHGESAWNLENR acquired using a hybrid LTQ linear ion trap -Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer. The a1 / pHis immonium ion along with the b- and y- series fragment ions are all consistent with the site of phosphorylation localized to the His1 position of the peptide (H11 in PGAM1). Phosphate losses observed are typical of His phosphorylation (20). The His11 phosphorylation site was confirmed using both the Sequest and Mascot database search engines with a statistically significant Expectation value of 0.078.

C. Extracts were prepared from HEK293 cells transiently transfected with N-terminally FLAG tagged PGAM1 (Ctrl) or N-terminally FLAG tagged PGAM1 where H11 was mutated to N (H11N). Expression of both FLAG tagged proteins in relation to endogenous PGAM1 was determined by Western blot using an anti-PGAM1 antibody as shown. The same extracts were incubated with 32P-labeled PEP and phosphorylation of PGAM1 determine by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography as shown.

D. rPGAM1 was incubated with a cell extract containing 18O-phosphate-labeled PEP and normal isotopic (16O-phosphate) ATP prior to recovery of the H11 containing tryptic peptide by HPLC as described in (A). This peptide was analyzed by microcapillary LC/MS using the high mass accuracy of the FT-MS-only scan in a LTQ Orbitrap-XL mass spectrometer at 30,000 resolution obtaining sub 2ppm mass accuracy. The peaks at m/z 697.79, 698.79 and 699.79 represent the doubly charged phosphorylated peptide pHGESAWNLENR that is heavy by two, four and six mass units corresponding to the incorporation of one, two, and three 18O labeled oxygen atoms respectively. The peak at m/z 696.79 represents the phosphorylated peptide containing unlabeled oxygen atoms.

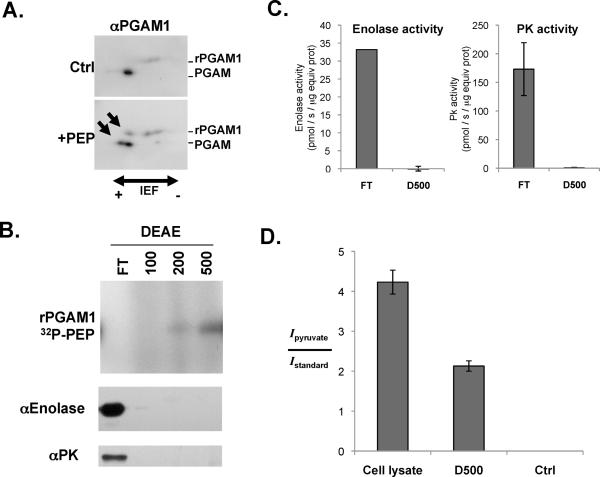

Association of PGAM1 phosphorylation with pyruvate generation from PEP in the absence of pyruvate kinase

Because the 32P-phosphate (and 18O-phosphate) from PEP is transferred to the catalytic histidine of PGAM1, we wondered whether we were observing a net increase in H11 phosphorylation of PGAM1 or merely observing an exchange of phosphate already present on PGAM1 with phosphate from PEP (as can occur during the interconversion of 2PG and 3PG). To address this issue, we added recombinant PGAM1 to a cell extract in the presence or absence of PEP. These extracts were then subjected to 2D gel electrophoresis and analyzed by Western blot with an antibody to PGAM. Consistent with PEP phosphorylation of H11, a new more acidic isoelectric species of both endogenous and recombinant PGAM1 was detected in the PEP-containing lysate (Fig. 4A). No change in the isoelectric forms of PGAM1 was observed when lysates were incubated with ATP instead of PEP (Fig. S10A). To confirm that this species did indeed represent the H11-phosphorylated form of PGAM1, we added PEP to a cell lysate to phosphorylate PGAM1 and then incubated the reaction either at neutral pH or at pH 2 to chemically disrupt H11 phosphorylation. Analysis of 2D Western blots with an antibody to PGAM1 showed that incubation at pH 2 resulted in loss of the most acidic PGAM1 species (Fig. S10B). Therefore we concluded that 2D Western blots could be used to assess H11 phosphorylation status in cells. These data also demonstrate that PEP can cause a net increase in H11 phosphorylated PGAM1, and that the phosphorylation of PGAM we observe cannot be accounted for by exchange of the PEP phosphate with a previously phosphorylated H11.

Fig. 4. Association of PGAM1 phosphorylation with conversion of PEP into pyruvate in the absence of pyruvate kinase.

A. Recombinant PGAM1 (rPGAM1) was added to a HEK293 cell extract in the absence (Ctrl) or presence of PEP (+PEP). The reactions were analyzed using 2D IEF and SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot using an anti-PGAM1 antibody as shown. The newly resolved, more acidic species present only in the PEP containing reaction are indicated by arrows.

B. A HEK293 cell lysate was centrifuged at 100,000 × g and the S100 supernatant fractionated over a weak anion exchange (DEAE) column. The flow through (FT) and fractions eluted sequentially with 100 mM, 200 mM and 500 mM NaCl were collected and incubated with rPGAM1 and 32P-PEP. The ability of each fraction to phosphorylate PGAM1 was determined by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography as shown. The amount of enolase and pyruvate kinase (PK) in each fraction was determined by Western blot as shown.

C. The enolase activity was determined in the FT and 500 mM NaCl (D500) fractions described in (B) as shown. In addition, the ADP-dependent pyruvate kinase activity in each fraction was also determined as shown.

D. 2,3-13C-labeled PEP was incubated with a HEK293 cell S100 fraction (Cell lysate) or the 500 mM NaCl fraction described in C (D500) which contained the PGAM1 phosphorylating activity. 13C-labeled PEP was also incubated under the identical reaction conditions in the absence of any protein (Ctrl). Quantification of the conversion of 13C-labeled PEP to 13C-labeled pyruvate was measured by integrating the intensity of the pyruvate peak and dividing by the intensity of the internal standard consisting of 2 mM DSS for each [1H,13C] HSQC spectra collected. This ratio is graphed for each condition as shown.

To determine if H11 phosphorylated PGAM1 is catalytically competent for enzymatic activity, we assayed the ability of PEP-phosphorylated PGAM1 to convert 3PG to 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG), the intermediate in 3PG to 2PG conversion (23). Recombinant His-tagged PGAM1 was incubated with PEP and cell extract to allow phosphorylation on His11 and the protein was recovered through association with Ni-agarose beads. Addition of 3PG to the recovered PGAM1 resulted in 2,3-BPG production as determined by selected reaction monitoring (SRM) using hybrid quadrupole linear ion trap mass spectrometry (Fig. S11). Thus, phosphorylation of PGAM1 by PEP leads to an enzyme species that is active to carry out the known enzymatic function of PGAM1.

We fractionated a cell lysate over a weak anion exchange column and isolated the PEP-dependent PGAM1 phosphorylating activity in a fraction that was separate from the enolase-containing fraction as determined by both enzyme activity assays and Western blot (Fig. 4, B and C; Fig. S12A). The fraction containing the PGAM1 phosphorylating activity was also separated from pyruvate kinase as determined by both enzyme activity assay and Western blot. In support of this finding that pyruvate kinase is not involved in the transfer of phosphate to PGAM1, we found that shRNA knockdown of pyruvate kinase resulted in the enhanced ability of a cell lysate to transfer 32P from 32P-labeled PEP to PGAM1 with no change in the level of PGAM1 protein (Fig. S12, B–D). It has been reported that a complex containing the nucleoside diphosphate kinase nm23 and GAPDH can phosphorylate PGAM1 (24). However, neither GAPDH nor nm23 co-purify in significant quantities with the PEP-dependent PGAM1-phosphorylating activity (Fig. S12E), suggesting that these proteins are not involved in the activity we observe.

We further investigated the consequences of metabolizing PEP through phosphotransfer to PGAM1. To test whether PEP is converted to pyruvate during the phosphotransfer reaction, we incubated the anion exchange fraction containing the PGAM1 phosphorylating activity (D500 fraction) with 13C-labeled PEP and recombinant PGAM1. Similar reactions with a whole cell lysate served as a positive control and a 13C-labeled PEP sample that contained no cellular material served as a negative control. We then extracted metabolites from the resulting reactions to study the products derived from the labeled PEP by [1H, 13C] HSQC NMR (25). We detected 13C-labeled pyruvate in the whole cell lysate as determined by an isolated peak corresponding to a 13C-labeled methyl group of pyruvate (26). No pyruvate was observed in the mock-treated control, indicating that PEP did not undergo spontaneous dephosphorylation and tautomerization to pyruvate under the reaction conditions. Incubation with the anion exchange fraction containing the PGAM1 phosphorylating activity also caused generation of pyruvate. The amount of 13C-labeled pyruvate produced by the D500 fraction was approximately 50% of the amount produced by a whole cell lysate (Fig. 4D). Thus, one or more factors in the partially purified fraction from cell lysates lacking pyruvate kinase mediates PEP-dependent phosphorylation of PGAM1 and conversion of PEP to pyruvate.

13C-labeled pyruvate was produced from PEP in the D500 fraction at a rate of approximately 30–60 μM/minute. Given that the number of PGAM1 molecules in this fraction is small relative to the number of PEP molecules consumed, this fraction must also contain the ability to release inorganic phosphate (Pi). To determine whether Pi production from PEP also occurred in this fraction, we incubated the D500 fraction with 32P-labeled PEP and recombinant PGAM1 and assessed the release of 32Pi over time (Fig. S13A). We also tested whether the rate of Pi production was enhanced by PGAM1. Addition of PGAM1 should have no impact on (or decrease) the rate of Pi production from PEP if this reaction is independent of PEP-mediated PGAM1 phosphorylation. However, PGAM1 addition stimulated Pi production in the fraction lacking pyruvate kinase (Fig. S13B) suggesting a link between PEP-dependent PGAM1 phosphorylation and PEP to pyruvate conversion with Pi release. These results suggest that release of Pi from either phosphorylated PGAM1, PEP, or both occurs in this fraction; and accounts for how PEP to pyruvate conversion can occur at a rate that is super-stoichiometric to the amount of PGAM1 present.

Selective detection of PGAM1 H11 phosphorylation and altered glycolytic regulation in PKM2-expressing cells and tumor tissues

To test whether increased H11 phosphorylation of PGAM1 might be characteristic of PKM2-expressing cells as a consequence of their lower pyruvate kinase activity, we engineered H1299 and A549 lung cancer cells to express either PKM1 or PKM2 (4). PGAM1 expression was similar regardless of which pyruvate kinase isoform was present (Fig. S14A). However, when the isoelectric forms of PGAM1 were assessed by 2D Western blot, only lysates prepared from PKM2-expressing cells had detectable amounts of the most acidic species that corresponds to H11-phosphorylated PGAM1 (Fig. 5A, Fig. S14B). Thus, switching cells from PKM2 to PKM1 expression reduced the amount of H11 phosphorylated PGAM1.

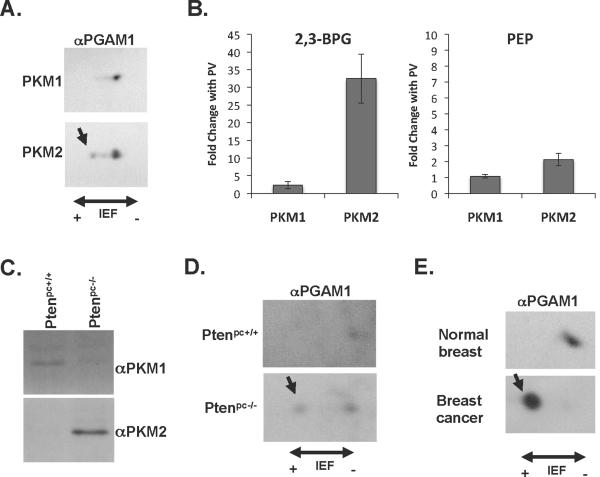

Fig. 5. Phosphorylation of PGAM1 H11 in cells and tissues expressing PKM2.

A. Lysates from A549 lung cancer cells engineered to express either PKM1 or PKM2 were subjected to 2D IEF and SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot using an anti-PGAM1 antibody (αPGAM1) as shown. The most acidic species corresponding to H11 phosphorylation is indicated with an arrow.

B. Metabolites were extracted from H1299 cells engineered to express either PKM1 or PKM2 that were untreated, or treated with the phosphatase inhibitor pervanadate (PV) for 10 minutes to acutely inhibit PKM2. PKM2 activity is decreased by PV treatment while PKM1 activity is not changed (5). The levels of 2,3-BPG and PEP in each extract were determined by mass spectrometry, and the changes in 2,3-BPG and PEP levels resulting from PV treatment are shown for both PKM1- and PKM2-expressing cells.

C. Prostate tissue was removed from 12 week old mice harboring a conditional allele of the Pten tumor suppressor gene which also did (Ptenpc−/−) or did not (Ptenpc+/+) contain a transgene to express Cre recombinase in the prostate to delete Pten. The Ptenpc−/− was confirmed to have high grade prostate neoplasia by histology. The expression of PKM1 or PKM2 in each tissue was determined by Western blot as shown.

D. Prostate tissue lysates from the same mice described in (E) were subjected to 2D IEF and SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot using an anti-PGAM1 antibody as shown. The most acidic species corresponding to H11 phosphorylation is indicated with an arrow.

E. A breast tumor (cancer) was removed from 9-month-old mouse harboring a conditional allele of the Brca1 tumor suppressor gene and a transgene to express Cre recombinase in the breast to delete Brca1. Normal breast tissue was removed from a mouse not expressing Cre and hence where Brca1 was not deleted in the breast. Normal breast expresses PKM1, breast tumors express PKM2 (4)(Fig. S14C). Lysates from the normal breast tissue and the breast tumor were subjected to 2D IEF and SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot using an anti-PGAM1 antibody as shown. The most acidic species corresponding to H11 phosphorylation is indicated with an arrow.

Accumulation of PEP in cells should enhance PGAM1 phosphorylation. Because the PGAM1 mutase reaction involves a 2,3-BPG intermediate (23), this in turn should drive conversion of 3PG to 2,3-BPG (Fig. S15). Accordingly, acute inhibition of pyruvate kinase in cells with PEP-dependent PGAM1 phosphorylation activity should increase 2,3-BPG levels. To test this hypothesis, PKM2 activity was acutely inhibited in cells by addition of pervanadate to increase protein tyrosine phosphorylation (5). Pervanadate has no effect on PKM1 activity (5), thus comparing the response of PKM2-expressing cells to PKM1-expressing cells separates the effects of acute PKM2 inhibition from other effects of pervanadate on metabolism. Acute inhibition of PKM2 leads to an approximately 2-fold increase in PEP and a yet larger increase in 2,3-BPG (Fig. 5B), suggesting that glycolysis involving PGAM1 phosphorylation by PEP occurs in PKM2 expressing cells, and that relative flux through this alternative pathway is increased when PKM2 is inactivated by interaction with tyrosine phosphorylated proteins.

Tumors express PKM2 whereas PKM1 is expressed in many normal tissues (3, 4). To determine if a correlation between PGAM1 H11 phosphorylation status and PKM2 expression could also be observed for cancers in vivo, we analyzed tissues from animals by 2D Western blot with an antibody to PGAM. PKM1 was expressed in normal prostate tissue whereas the neoplastic prostate tissue expressed PKM2 (Fig. 5C). Analysis of these same cell lysates by 2D Western blot with an anti-PGAM1 antibody revealed that the isoelectric species corresponding to H11 phosphorylated PGAM1 was only detectable in the neoplastic prostate tissue (Fig. 5D). In a mouse with breast-specific deletion of the Brca1 tumor suppressor gene, breast tumor tissue had an even more dramatic shift in isoelectric migration of PGAM1 associated with the H11 phosphorylated species (Fig. 5E) and this correlated with expression of PKM2 (Fig. S14C). Thus, PEP-dependent phosphorylation of H11 on PGAM1 likely occurs in tumors as well as in cell lines expressing PKM2.

Discussion

We have shown that the high-energy phosphate of PEP can be transferred to the catalytic histidine (H11) of PGAM1 by an enzymatic process that does not require enolase-dependent conversion to 2PG. Phosphorylation of H11 is known to be required for PGAM1 catalytic function and 2,3-BPG has been characterized as the co-factor required for PGAM1 activation (16). Our results reveal that PGAM1 can also be activated by PEP. The activity that catalyzes phosphate transfer from PEP to PGAM1 is separable from the well-known PEP metabolizing enzymes, pyruvate kinase and enolase, and the byproduct of the reaction appears to be pyruvate. Importantly, we find that in cells expressing PKM2, a significant fraction of PGAM1 migrates at an isoelectric point consistent with the phospho-H11 species and that replacing PKM2 with the more active PKM1 isoform results in disappearance of this species. These results are consistent with a model where PKM2-expressing cells utilize a greater fraction of PEP for charging PGAM1 and less for the synthesis of ATP.

Despite the fact that PGAM1 has not been considered a rate-limiting enzyme in glycolysis, the differential H11 phosphorylation of PGAM1 we observed in PKM2- versus PKM1-expressing cells and tissues suggests that this enzyme may have a previously unappreciated regulatory function in controlling glycolysis in proliferating cells. PGAM1 is unique among the glycolytic enzymes in that its transcription is regulated by the tumor suppressor p53 (27), and increased expression of PGAM1 has been reported to immortalize primary cells through an unknown mechanism (28). PGAM1 was also identified as the target of a compound from a chemical genomics screen for molecules that inhibit breast cancer cell growth (29). Thus, one important consequence of down-regulating PKM2 activity by tyrosine kinases may be to increase H11 phosphorylated PGAM1. Phosphorylation of H11 on PGAM1 increases the mutase function of the enzyme. This generates a positive feedback loop such that production of PEP increases the enzymatic activity of PGAM1. One possibility is that this feedback loop may promote the redistribution of metabolites upstream of PGAM1 into biosynthetic pathways that branch from glycolysis.

We propose that in addition to pyruvate kinase, another activity to convert PEP into pyruvate may be active in cells (Fig. S15). The existence of such an alternate glycolytic pathway may explain how cancer cells with less pyruvate kinase activity continue to display a high rate of glycolysis. The rate of PEP to pyruvate conversion observed in the absence of pyruvate kinase is comparable to the Vmax of pyruvate kinase (65 μM/min (30)), suggesting that this activity could account for a significant amount of the pyruvate produced from glucose in cells with a less active form of pyruvate kinase. When catalyzed by pyruvate kinase, the conversion of PEP into pyruvate is coupled to ATP generation (31). Phosphorylation of PGAM1 by PEP does not directly generate ATP but generates pyruvate. In order for a significant amount of pyruvate to be generated by this alternative pathway, the phosphohistidine of PGAM1 must turnover. While conversion of 3PG to 2PG does not result in net loss of phosphohistidine, spontaneous hydrolysis of phosphohistidine on PGAM1 does occur (16). Also, 2,3-BPG can be produced by addition of 3PG or 2PG to phosphorylated-PGAM1 (reversal of the 2,3-BPG charging reaction) and the resulting 2,3-BPG can be hydrolyzed to 2PG and inorganic phosphate (32). Finally, it is possible that the activity responsible for PGAM1 phosphorylation can also act as a PEP phosphatase. Each of these possibilities results in the net conversion of PEP to pyruvate and Pi with no ATP synthesis. This lack of ATP synthesis may allow cells to metabolize glucose by a modified glycolysis that does not generate ATP and provides an advantage to proliferating cells. Historically, efforts to understand aerobic glycolysis stressed the importance of ATP consumption to allow the high rate of glucose metabolism observed in tumor cells (33). Cells must avoid ATP production in excess of demand to avoid allosteric inhibition of phosphofructokinase and other rate limiting steps in glycolysis that are inhibited by a high ATP/AMP ratio (31). Thus, inhibition of PKM2 by cell growth signals may serve to uncouple the ability of cells to assimilate nutrients into biosynthetic pathways from the production of ATP, and account for why PKM2 activity is decreased in rapidly dividing cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Carrecedo and P.P. Pandolfi for normal and neoplastic prostate tissue, and L. Burga and G. Wulf for normal breast and breast tumor, G. Bellinger for assistance with mouse dissection, M. Sasaki for help generating constructs, V. Vyas, A. Subtelny, L. Freimark, X. Yang, L. Schmidt, and M. Balastik for technical assistance, M. Bayro and S. Hyberts for help with processing the NMR spectra, and A. Shaywitz, J. Hutti, C. Benes, D. Anastasiou, A. Couvillion, and A. Saci for helpful discussions. This work was partially supported by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (MVH), the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (MVH), the American Cancer Society (JWL), DF/HCC (JMA, JWL), and by grants from the NIH (1K08CA136983 to MVH, 5P30CA006516-43 to JMA, 5 T32 CA009361-28 to JWL, R21/R33 DK070299 and P0147467 to GW, R01-GM56302 and P01CA089021 to LCC, and 1P01CA120964-01A to JMA and LCC).

References

- 1.Jones RG, Thompson CB. Genes Dev. 2009 Mar 1;23:537. doi: 10.1101/gad.1756509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heiden M. G. Vander, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Science. 2009 May 22;324:1029. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazurek S, Boschek CB, Hugo F, Eigenbrodt E. Semin Cancer Biol. 2005 Aug;15:300. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christofk HR, et al. Nature. 2008 Mar 13;452:230. doi: 10.1038/nature06734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christofk HR, Heiden M. G. Vander, Wu N, Asara JM, Cantley LC. Nature. 2008 Mar 13;452:181. doi: 10.1038/nature06667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hitosugi T, et al. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra73. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dombrauckas JD, Santarsiero BD, Mesecar AD. Biochemistry. 2005 Jul 12;44:9417. doi: 10.1021/bi0474923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saier MH, Jr., Reizer J. Mol Microbiol. 1994 Sep;13:755. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deutscher J, Francke C, Postma PW. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006 Dec;70:939. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00024-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burnell JN, Hatch MD. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1984 May 15;231:175. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(84)90375-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burnell JN, Hatch MD. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1986 Mar;245:297. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(86)90219-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minakami S, Yoshikawa H. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1965 Feb 3;18:345. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(65)90711-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lagunas R, Gancedo C. Eur J Biochem. 1983 Dec 15;137:479. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klumpp S, Krieglstein J. Eur J Biochem. 2002 Feb;269:1067. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Besant PG, Attwood PV. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005 Dec 30;1754:281. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fothergill-Gilmore LA, Watson HC. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1989;62:227. doi: 10.1002/9780470123089.ch6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee ME, Nowak T. Biochemistry. 1992 Feb 25;31:2172. doi: 10.1021/bi00122a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olsen JV, et al. Nat Methods. 2007 Sep;4:709. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medzihradszky KF, Phillipps NJ, Senderowicz L, Wang P, Turck CW. Protein Sci. 1997 Jul;6:1405. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kleinnijenhuis AJ, Kjeldsen F, Kallipolitis B, Haselmann KF, Jensen ON. Anal Chem. 2007 Oct 1;79:7450. doi: 10.1021/ac0707838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hohenester UM, Ludwig K, Krieglstein J, Konig S. Anal Bioanal Chem. Jan 10; doi: 10.1007/s00216-009-3372-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zu XL, Besant PG, Imhof A, Attwood PV. Amino Acids. 2007;32:347. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0493-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blattler WA, Knowles JR. Biochemistry. 1980 Feb 19;19:738. doi: 10.1021/bi00545a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engel M, Mazurek S, Eigenbrodt E, Welter C. J Biol Chem. 2004 Aug 20;279:35803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402768200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kay LE, Keifer P, Saarinen T. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:10663. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wishart DS, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007 Jan;35:D521. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheung EC, Vousden KH. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010 Jan 8;8 doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.006. epub Jan. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kondoh H, et al. Cancer Res. 2005 Jan 1;65:177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans MJ, Saghatelian A, Sorensen EJ, Cravatt BF. Nat Biotechnol. 2005 Oct;23:1303. doi: 10.1038/nbt1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ainsworth S, MacFarlane N. Biochem J. 1973 Feb;131:223. doi: 10.1042/bj1310223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lehninger AL, Nelson DL, Cox MM. Principles of Biochemistry. ed. 2nd Worth Publishers; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho J, King JS, Qian X, Harwood AJ, Shears SB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Apr 22;105:5998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710980105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Racker E. J Cell Physiol. 1976 Dec;89:697. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040890429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.