Abstract

A 60-year-old woman presented after a fall and was noted to have ascites. She had a history of ulcerative colitis. History and physical examination did not reveal the likely aetiology of the ascites, but a sample showed it to be a blood-stained exudate. A malignant cause appeared likely, cross-sectional imaging was arranged and tumour markers sent. CA125 was 34 IU/ml (0–30); α-fetoprotein (AFP) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) were normal. However, CA19-9 was 2880 U/ml (0–31). Pancreatic carcinoma or cholangiocarcinoma were of prime concern, but a CT scan and MRI imaging were normal. At laparoscopy a benign ruptured ovarian cyst was detected, and ascites drained. CA19-9 returned to normal and the patient remains well 9 months later. This case demonstrates how tumour markers may be misleading in the context of diagnostics, and is the highest reported example of CA19-9 rise in the context of benign ascites and benign ovarian pathology.

BACKGROUND

Discerning the cause of ascites can be a challenging clinical problem. Tumour markers are often used in clinical practice when malignancy is considered a likely cause. We want to alert primary care practitioners, doctors, oncologists, gastroenterologists and gynaecologists to this case that demonstrates the need to use tumour markers appropriately to avoid unnecessary tests and anxiety, and highlights an unusually high CA19-9 level resulting from a ruptured benign ovarian cyst.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 60-year-old woman was referred to our department from her doctor with ascites of unknown aetiology. She had presented 4 days previously after a fall that had caused facial bruising, but no other obvious injury. Her past medical history included bullous pemphigoid, hypertension, depression and ulcerative colitis, which had been quiescent for 30 years. Her medications were lisinopril 10 mg, citalopram 20 mg, furosemide 20 mg, prednisolone 5 mg, minocycline mr 100 mg daily and alendronate 70 mg/week.

She was a housewife, living with her husband, and she drank no alcohol. She had stopped smoking 20 years ago. Physical examination revealed a well woman with facial bruising, withdrawn affect and a distended abdomen due to ascites, with peau d’orange but no organomegaly. There were no other clinical signs of chronic liver disease or heart failure.

INVESTIGATIONS

Her white blood cell (WBC) count was 12.6 (normal differential), platelets 456, with normal haemoglobin and clotting. Urea and electrolytes, liver function tests, calcium and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were all normal. Her C-reactive protein was 100 mg/litre. Urine dipstick demonstrated no protein but was positive to leukocytes and nitrites and later grew Escherichia coli on culture.

The ascites was tapped, was visibly blood-stained, and showed total protein of 80 g/litre, albumin of 54 g/litre (serum albumin 41 g/litre), a normal amylase and LDH. Ascites microscopy and Gram stain revealed no organisms, a WBC count of 5526/μl (polymorphs 5440/μl) and red blood cell count of 28 160/μl. There was no growth on standard culture, or on stain and culture for mycobacteria. In the presence of a blood-stained exudate, and concern over malignancy, cross-sectional imaging was performed and tumour markers were sent. CA125 was 34 IU/ml (normal range 0–30), α-fetoprotein (AFP), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CA15-3 were all normal; however CA19-9 was 2880 U/ml (normal range 0–31).

A transthoracic echocardiogram was normal.

A CT scan of the abdomen with contrast demonstrated large volume ascites but normal intra-abdominal organs and peritoneum, and no cause for the ascites found. The CA19-9 had raised particular concerns of an occult pancreatic malignancy or cholangiocarcinoma, the latter perhaps in concert with undiagnosed primary sclerosing cholangitis (ulcerative colitis (UC) associated). MRI of the pancreas and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) were normal however. Although an initial pelvic ultrasound had reportedly shown normal ovaries, a transvaginal ultrasound demonstrated a left ovarian mass. At laparoscopy a macroscopically benign ruptured ovarian cyst was detected and biopsied; 6 litres of ascites was drained fully.

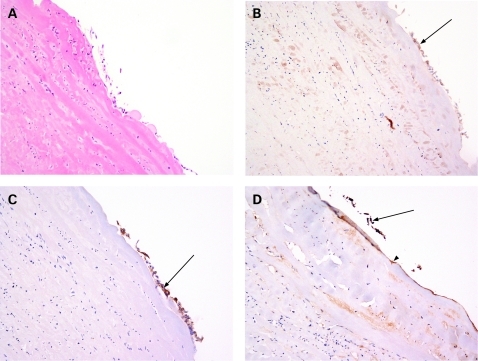

Histology of the cyst confirmed it was benign, showing an attenuated degenerate epithelium (fig 1A). As expected, CA125 weakly stained this epithelium (fig 1B), as did CEA (fig 1C, arrows to brown stain), showing the cyst to be most likely a mucinous cystadenoma. CA19-9 also stained the attenuated epithelial cells focally present and the basement membrane diffusely (fig 1D, arrow to brown-stained epithelium; arrowhead to basement membrane), an unusual finding in ovarian cysts, confirming it as the most likely source of serum CA19-9. Pancreatic carcinomas can metastasise to the ovary, but the detailed MR imaging had already excluded this possibility.

Figure 1.

A. Cyst wall biopsy; degenerate benign indeterminate cyst. B. CA125 immunostain. C. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) immunostain. D. CA19-9 immunostain.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Pancreatic carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, other intra-abdominal malignancy, other causes of exudative ascites (eg, tuberculosis).

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The cyst may have ruptured due to the fall, but the presence of peau d’orange and volume of ascites (6 litres) suggests a longer history.

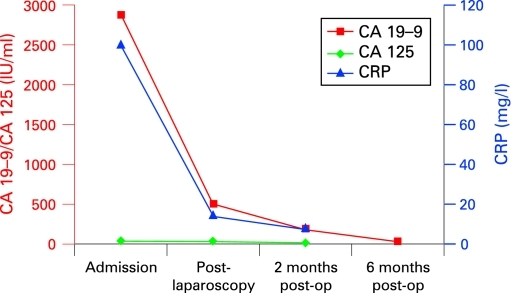

All blood tests subsequently returned to normal (see fig 2), including CA19-9.

Figure 2.

Tumour markers and C-reactive protein (CRP).

The patient remains well, with no recurrence of ascites, 9 months later.

DISCUSSION

The serum carbohydrate antigen CA19-9, a sialylated Lewis blood group antigen, was first described by its monoclonal antibody by Koproswki in 1981.1 The recommended use for CA19-9 is as follow-up and prognosis for a confirmed pancreatic carcinoma, or to aid diagnosis of a pancreatic mass or biliary stricture. In suspected pancreatic cancer mass CA19-9 has a sensitivity and specificity of around 70% and 80%, respectively.2 About 10% of the general population is—by inheritance—negative for this Lewis blood group antigen and, thus, will not express CA19-9 if they develop pancreatic carcinoma.

Isolated low-level elevation of CA19-9 has been described in benign ovarian dermoid cysts (teratomas) in three case reports,3–5 and also reported in up to 50% of teratomas with malignant change,3 but our case is the highest reported rise associated with benign ovarian pathology (the previous being 1430 U/ml).4 The immunohistochemistry we performed on this cyst suggested it as the source of CA19-9. It is possible however that, at least in part, the detectable serum CA19-9 was due to the resultant contact of cyst fluid with the peritoneum, and/or the presence of an inflammatory ascites.

There are no reported cases of elevated CA19-9 of this magnitude in benign ascites. Two previous studies6,7 have assessed tumour markers in the diagnosis of ascites aetiology. Chen et al6 compared 123 patients with either malignancy-related ascites or benign ascites, and found statistically significant differences in serum CA19-9 levels between the groups. Using a cut-off level of 50 U/ml, CA19-9 had a sensitivity and specificity of 65.5% and 93.6%, respectively; their conclusion being that it is not sensitive enough, or cost effective, as a diagnostic marker. Sari et al7 performed a similar study of 76 patients and came to the same conclusion. Neither study reported median CA19-9 levels in benign ascites above 100.9 U/ml.

Although serum tumour markers (TM) in general are often measured in hospitalised patients, their use is often unjustified either in clinical or economic terms. Arioli et al8 showed that 62% of hospital inpatients had a tumour marker requested, 79% as part of a diagnostic work-up, and only 5% following existing published evidence. Loi et al9 showed that the most popular use of TM is for screening. They looked at 476 patients who had TM requested, and showed it to be helpful in only 29% of patient management; it aided diagnosis in only 4 patients.

In summary this case demonstrates that CA19-9 levels as high as 3000 U/ml can be due to benign intra-abdominal disease, and it highlights the problems caused by the use of tumour markers outside of the available evidence base.

LEARNING POINTS

Marked elevations of CA19-9 are possible in benign ovarian tumours, in the presence of ascites.

Tumour markers should be used within the available evidence base. If not, the results are difficult to interpret, can lead to unnecessary anxiety and investigations and increase the cost of medical care.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koprowski H, Herlyn M, Steplewski Z, et al. Specific antigen in serum of patients with colon carcinoma. Science 1981; 212: 53–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boeck S, Stieber P, Holdenrieder S, et al. Prognostic and therapeutic significance of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 as tumor marker in patients with pancreatic cancer. Oncology 2006; 70: 255–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nanayakkara S, Ali S, Gilmour K. Increased serum carcinomic antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) in a dermoid cyst. J Obst Gynaecol 2007; 27: 96–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atabekoglu C, Bozac EA, Tezcan S. Elevated carbohydrate antigen 19-9 in a dermoid cyst. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2005; 91: 262–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagata H, Takahashi K, Yamane Y, et al. Abnormally high values of CA 125 and CA 19-9 in women with benign tumors. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1989; 28: 165–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen S, Wang S, Chi-Wen L, et al. Clinical value of tumour markers and serum-ascites albumin gradient in the diagnosis of malignancy-related ascites. J Gastoenterol Hepatol 1994; 9: 396–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sari R, Yildrim B, Sevinc A, et al. The importance of serum and ascites fluid alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, CA 19-9, and CA 15-3 levels in differential diagnosis of ascites etiology. Hepatogastroenterology 2001; 48: 1616–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arioli D, Pipino M, Boldrini E, et al. Tumour markers in internal medicine: a low-cost test or an unnecessary expense? A retrospective study based on appropriateness. Intern Emerg Med 2007; 2: 88–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loi S, Haydon A, Shapiro J, et al. Towards evidence-based use of serum tumour marker requests: an audit of use in a tertiary hospital. Int Med J 2004; 34: 545–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]