Abstract

PURPOSE

p27 localization and expression has prognostic and predictive value in cancer. Little is known regarding expression patterns of p27 in renal cell carcinoma (RCC), or how p27 participates in disease progression or response to therapy.

EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

RCC-derived cell lines, primary tumors and normal renal epithelial cells were analyzed for p27 expression, phosphorylation (T157 of the NLS) and subcellular localization. RCC-derived cell lines were treated with PI3K and mTOR inhibitors and effects on p27 localization assessed. The potential contribution of cytoplasmic p27 to resistance to apoptosis was also evaluated.

RESULTS

p27 was elevated in tumors compared with matched controls, and cytoplasmic mislocalization of p27 was associated with increasing tumor grade. Cytoplasmic localization of p27 correlated with phosphorylation at T157, an AKT phosphorylation site in the p27 NLS. In RCC cell lines, activated PI3K/AKT signaling was accompanied by mislocalization of p27. AKT activation and phosphorylation of p27 was associated with resistance to apoptosis, and siRNA knockdown of p27 or relocalization to the nucleus increased apoptosis in RCC cells. Treatment with the PI3K inhibitors LY294002 or wortmannin resulted in nuclear relocalization of p27, whereas mTOR inhibition by rapamycin did not.

CONCLUSIONS

In RCC, p27 is phosphorylated at T157 of the NLS, with increasing tumor grade associated with cytoplasmic p27. PI3K inhibition (which reduces AKT activity) reduces T157 phosphorylation and induces nuclear relocalization of p27 whereas mTOR inhibition does not. Clinical testing of these findings may provide a rational approach for use of mTOR and PI3K/AKT pathway inhibitors in patients with RCC.

Keywords: p27, localization, AKT, mTOR, apoptosis

INTRODUCTION

p27 is a member of the Cip/Kip family of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs), which function to negatively regulate cell cycle progression. p27 interacts with cyclin D, E and A dependent kinases (CDKs), facilitating nuclear import of cyclin D-CDK4/6 complexes and inactivating cyclin A- and cyclin E-CDK2 complexes in the nucleus (1). While aberrant cell cycle progression is a hallmark of tumorigenesis and defects in cell cycle regulation are common in cancer cells, mutations in the p27 gene in cancer are rare. Rather, p27 is regulated predominantly by posttranslational modifications, primarily phosphorylation, which determine protein stability and subcellular localization (2-4). Intriguingly, p27 protein degradation is mediated by different processes in the cytosol and nucleus, potentially contributing to cytoplasmic or nuclear accumulation (5).

In tumors, p27 activity is regulated via several different mechanisms. One of the primary regulatory mechanisms is post-translational modification, most commonly phosphorylation, which targets p27 for degradation or sequesters it in the cytoplasm, where it is unable to fulfill its nuclear function as a CKI (3, 4). p27 can be phosphorylated on Threonine 157 by AKT causing it to localize to the cytoplasm (6, 7). The correlation of high levels of Akt and cytoplasmic p27 in breast cancer may account for unrestricted CDK2 activity in the nucleus of these tumors to enable continuous progression through the cell cycle (8). Recently, it has become appreciated that p27 sequestered in the cytoplasm exhibits gain-of-function in tumors, which in contrast to the tumor suppressor function of nuclear p27, serves to inhibit apoptosis and regulate the decision to undergo an autophagic survival program (9, 10).

Renal cell carcinoma cell lines and primary tumors exhibit activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and elevated mTOR activity (11-13). The PTEN tumor suppressor, which negatively regulates PI3K signaling, may also participate in aberrant PI3K/AKT signaling in RCC. While PTEN mutations are rare in RCC, PTEN expression is frequently reduced (14, 15) and correlates with increased phosphorylation/activation of AKT in these tumors (16). However, while p27 is known to be a target of PI3K/AKT signaling, little is known about the impact of aberrant PI3K/AKT signaling on p27 localization and function in RCC.

We report here that activation of AKT signaling is a consistent feature of RCC-derived cell lines and primary tumors. AKT activation in RCC correlated with phosphorylation at T157 and cytoplasmic sequestration of p27. The presence of cytoplasmic p27 also correlated with tumor grade in RCC patients. In RCC cell lines, inhibition of PI3K/AKT signaling induced nuclear relocalization of p27, while mTOR inhibition had no effect on localization of this CKI. AKT activation and phosphorylation of p27 also correlated with resistance to apoptosis in RCC cell lines, with relocalization of p27 by PI3K/AKT inhibitors or siRNA knockdown of p27 increasing sensitivity to apoptosis in these cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and Reagents

Phospho-S6 (S235/236), S6, phospho-AKT (S473), and AKT antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). p27 (K5020) antibody was from BD Transduction Laboratories (San Diego, CA), beta-actin and lamin A/C antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Phospho-p27 T157, T198, and total p27 antibodies were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MA), and LDH antibody was from Chemicon (Temecula, CA). Secondary antibodies conjugated to HRP were purchased from Santa Cruz and secondary antibodies conjugated to FITC and Texas Red were purchased from Jackson Labs. LY294002 (20μM), wortmannin (200nM), and Rapamycin (0.2-2μM) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) and resuspended in DMSO as the vehicle.

Cell Lines

VHL+/+ Caki-1 cells were cultured in McCoy’s 5A and ACHN cells were grown in MEM, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone, Logan, Utah). VHL−/− RCC4 cells were cultured in DMEM and 786-O cells were maintained in RPMI, with 10% FBS. All cells were from ATCC and media were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Normal and tumor match UMRC2, 5, 6 and 7 renal cell lines were a kind gift from H. Barton Grossman (UT M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston TX), and were maintained in αMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, non – essential amino acids, sodium pyruvate, and penicillin-streptomycin-amphotericin B at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Western Analysis and Cell Fractionization

Tissue lysates were made in RIPA buffer (1X PBS, 0.1% SDS, 1% NP-40, and 12mM Sodium deoxycholate) and cell lines were lysed in 1X lysis buffer (20mM Tris-HCl pH7.5, 150mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, and 2.5mM Sodium pyrophosphate). All buffers contained 1X complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 1 and 2 (Sigma).

For fractionation, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and scraped into chilled hypotonic buffer (10mM HEPES pH7.2, 10mM KCl, 1.5mM MgCl2, 0.1mM EGTA) and broken by a Dounce homoginizer. After centrifugation at 3,000rpm, the supernatant was collected (cytoplasmic fraction) and the crude nuclei pellet was further homogenized in hypotonic buffer and washed in nuclear washing buffer (10mM Tris-HCl pH7.4, 0.1% NP40, 0.05% sodium deoxycholate, 10mM NaCl, and 3mM MgCl2) and centrifuged at 3,000rpm. Purified nuclei were lysed in high salt lysis buffer (20mM HEPES pH7.4, 0.5M NaCl, 0.5% NP40, and 1.5mM MgCl2). All buffers contained 1X complete protease inhibitor cocktail and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 1 and 2.

Immunohistochemistry and tissue microarrays (TMA)

TMAs were generated using a Beecher instrument with 0.6mm cores taken from the donor block and placed into the recipient block in triplicate for each case. For each block, there were four observations; “involvement”, “intensity”, grade and location. TMA images were acquired using the BLISS system (Bacus Laboratories,Inc.North Lombard, IL) and were scored using the TAD system (Biostatistics Department, MD Anderson Cancer Center) and the Biogenex iVISION image analysis system (4600 Norris Canyon Rd., San Ramon, CA., 94583). Cores were scored according to presence or absence of tumor, degree of tumor involvement (continuous variable), staining intensity (none, low, mid, high), and location of staining (cytoplasmic, nuclear or a combination thereof).

For immunohistochemistry, unstained slides were placed in a 60 degree oven for 20 minutes, air dried for 5 minutes, deparaffinized and rehydrated by three changes of xylene and 100% ethanol and two changes of 80% ethanol, rinsed three times with deionized water and placed in TBS. Slides were then placed in a 3% hydrogen peroxide blocking solution for 5 minutes, treated with heated 10 mM Citrate Buffer, pH 6.0 for 45 minutes, cooled for 20 minutes, and rinsed with deionized water and TBS. The primary antibody was incubated with the tissue for an hour, rinsed with deionized water three times and placed in TBS. Secondary antibody was incubated for 30 mins, rinsed three times with deionized water and placed in TBS. Excess buffer was removed and DAB applied to tissue and incubated for 8 minutes and rinsed with deionized water. DAB enhancer was followed with a rinse with deionized water and counter stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Immunocytochemistry

Localization of endogenous p27 was determined by immunofluorescence analysis with biotin-avidin signal amplification in renal cell carcinoma cell lines. Cells were plated onto glass chamber slides 18-24 hr before treatment, and treated as indicated. Cells were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min at 4°C, permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100/PBS for 10min at room temperature. Nonspecific antigens were blocked for 1 hr in PBS containing 7.5% BSA at 37°C, and endogenous biotin-avidin was blocked using Avidin/Biotin blocking kit (Zymed laboratories, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Subsequent staining was as described previously (17) with anti-p27 (K5020) primary antibody, biotin-conjugated donkey anti-mouse antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories), and FITC-conjugated Streptavidin (Invitrogen).

Apoptosis assays

40μg of cellular protein lysate was added to a 200μl reaction mixture containing the caspase substrate, 50uM Ac-DEVD-AFC (BIOMOL, Plymouth Meeting, PA) in 1X Caspase Reaction buffer (25mM HEPES, 50mM NaCl, 0,05% CHAPS, 5mM DTT, 0.5mM EDTA and 5% glycerol) for 90min at 37°C. Production of cleaved AFC by activated caspase in lysates was measured using a FL6000 Microplate Fluorescent Reader (BIO-TEK, Winooski, VT) with an excitation wavelength of 400nm and an emission wavelength of 505nm. Fluorimetric units were converted to μmoles/μg protein. Results are presented as fold-activation above the control.

siRNA experiments

Chemically synthesized siRNA SMARTpool of human p27 was purchased from Dharmacon (Thermo Fisher Scientifics) and the negative control siRNA used was siCOTROL (RISC-free #1, D-001220-01). 786-O cells were plated in 6-well plates 24hr prior to transfection, and transfection was performed as described previously (17). Knockdown efficiency was determined by Western analysis 48 hr post-transfection.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistical analyses were carried out, including percentage, proportions, means, and standard deviations. Chi-square test and t- test were used in univariate analyses of categorical and continuous variables, respectively. For the data analysis on multiple observations from a subject, a mixed-effects model was used to assess the tumor grade with the correlated data, and a logistic regression model was used to assess intensity (high versus low) by the generalized estimating equation (GEE) method (18), which is implemented in GENMOD procedure in SAS. This model allows the user to account for intra-subject correlations among repeated measurements on the same subject (the exchangeable working correlation matrix was specified in this study).

RESULTS

Expression and cytoplasmic sequestration of p27 in RCC

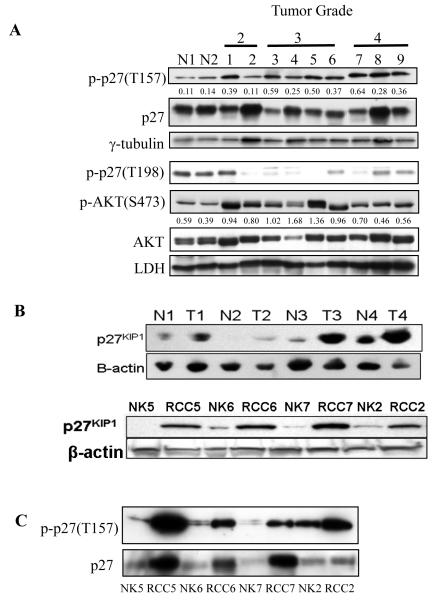

Two series of primary tumors (UT MD Anderson Cancer Center and the Mayo Clinic) from RCC patients were evaluated for p27 expression. Initially, western analysis was performed to assess p27 expression in tumors relative to normal kidney. As shown in Figure 1A, expression of p27 in primary tumors was high but heterogeneous, appearing comparable to that of normal kidney, which was confirmed by quantitative assessment of western blot intensities relative to loading controls (data not shown). To investigate the possible contribution of inter-individual differences to the observed heterogeneity in p27 expression levels, we also evaluated p27 expression in several patient-matched primary tumors and uninvolved kidney. As shown by representative patient-matched tissues in Figure 1B, although p27 levels varied between tumors of multiple stages, p27 expression was higher in all tumors relative to patient-matched normal tissue. This pattern of elevated p27 expression was observed in 6/8 stage 2 RCC examined relative to matched uninvolved kidney. Concordant with these data from primary tumors, in vitro cultures of isolated tumor cells expressed abundant p27, while this CKI was undetectable or expressed at very low levels in patient-matched normal cells (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. p27 expression in RCC.

(A) Western analysis of p27 and phosphop27 (T157), AKT and phosphoAKT (S473) in normal kidney and grade 2, 3 and 4 RCC. Relative ratio of phosphorylation at T157 (p27) and S473 (AKT) was calculated using densitometric analysis. (B) Western analysis of 4 representative pairs of normal and patient matched stage 2 RCC (upper panel) and cultured cells (lower panel) demonstrating increased p27 expression that was observed in tumor cells of (6 of 8 patients). RCC5 and RCC7 are derived from stage 3 tumors while RCC6 is from stage 1 and RCC2 from stage 4. (C) Western analysis for p27 phosphorylation at T157 in normal and patient-matched tumor cells from (B) showing increased p27 phosphorylation at T157 in tumor cells.

Interestingly, in the majority of tumors, phosphorylation of p27 at T157 was increased relative to normal kidney (p≤0.03 t-test) (Figure 1A), a site in the NLS of p27 known to regulate cytoplasmic localization (5). T157 is an AKT phosphorylation site (3-6), and tumors were confirmed by western analysis to express phosphorylated (active) AKT (Figure 1A). Although tumors again exhibited heterogeneity in levels of phosphoAKT, overall phosphoAKT was higher in tumors relative to normal kidney (p≤0.04 t-test), consistent with the observed elevated T157 p27 phosphorylation in these tumors (Figure 1A). Elevated T157 phosphorylation of p27 was also observed in cultured tumor cells relative to patient-matched normal controls (Figure 1C). In contrast, another phosphorylation site of p27, T198, known to be phosphorylated by AMPK (10) rather than AKT, exhibited no increase in phosphorylation in tumors compared with normal tissues (Figure 1A).

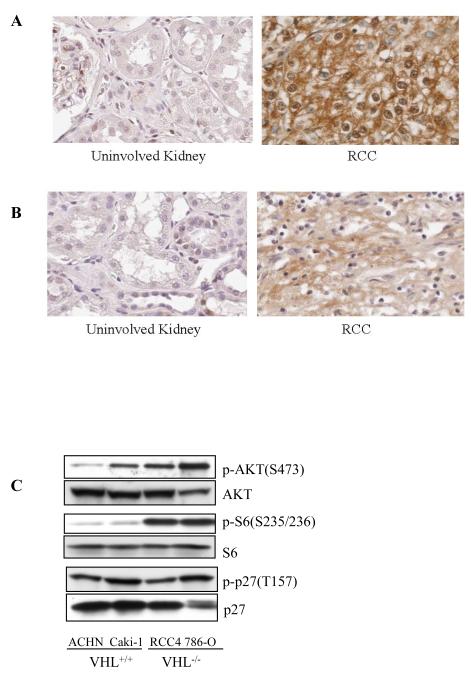

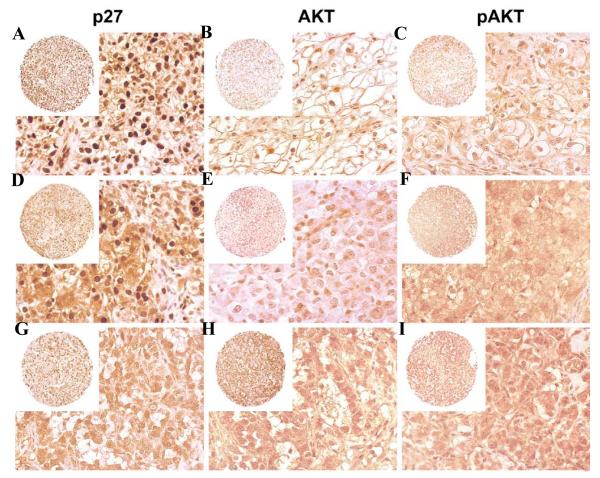

It has been demonstrated in other tumors that AKT phosphorylation at T157 in the p27 NLS causes it to become sequestered in the cytoplasm, where it is unable to inhibit its CDK targets in the nucleus (5, 8). Abundant p27 expression in RCC accompanied by phosphorylation at T157 suggested that functional inactivation of this CKI could be occurring in these tumors due to cytoplasmic sequestration, therefore we investigated p27 localization in these tumors. We observed that in many RCC, determination of p27 localization patterns by immunohistochemistry was confounded by the fact that the glycogen accumulation characteristic of the clear cell RCC phenotype often appeared to be occluding p27 immunoreactivity from the majority of the cytoplasm, compressing it to the cell periphery Nevertheless, in most cases it was possible to discern cytoplasmic from nuclear staining in a significant proportion of cells within the tumors, and score tumors based on their p27 localization pattern. As determined by immunohistochemistry of paraffin-embedded tumors (Figure 2A) and tissue microarrays (Figure 3 and Table 1), the majority of tumors exhibited cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for p27. Importantly, cytoplasmic versus nuclear localization of p27 correlated significantly (p≤0.001) with tumor grade, with loss of nuclear p27 increasing with tumor grade (Table 1). Immunohistochemistry also confirmed that similar to what was observed by western analysis, tumors expressed higher levels of phosphoAKT than uninvolved kidney (Figure 2B). p27 localization was also compared with levels of AKT immunoreactivity using tissue microarrays. Specificity for AKT immunoreactivity was demonstrated in normal kidney cores and between low versus high grade RCC (Supplemental Figure 1). Figure 3 illustrates staining patterns of tumors with predominately nuclear p27 and low AKT (total and phospho) activity (top panel) and tumors with predominately cytoplasmic p27 and high AKT (bottom panel). While in general tumors with predominately cytoplasmic p27 had the highest scores for total AKT (26% of cores with cytoplasmic p27 had strong AKT immunoreactivity versus 13-0% of cores with nuclear p27) and phospho-AKT (33% of cores with cytoplasmic p27 had strong phospho AKT immunoreactivity versus 23-10% of cores with nuclear p27) staining, (Supplemental Table 1), intra- and inter-tumor heterogeneity within the 20 cases examined prevented these data from reaching statistical significance. Therefore we turned to RCC-derived cell lines to further investigate a possible linkage between AKT activity and p27 phosphorylation and cytoplasmic localization in RCC.

Figure 2. p27 and AKT expression in RCC.

(A) Immunohistochemistry of representative normal and patient matched RCC illustrating expression and cytoplasmic p27 localization in tumor cells. (B) Immunohistochemistry of representative normal and patient matched RCC illustrating elevated phosphoAKT expression. (C) p27 and AKT expression and phosphorylation in RCC cell lines.

Figure 3. p27 and AKT immunoreactivity in RCC.

Panels A, B and C represent low-grade RCC from a single block. p27 is predominantly nuclear. Panels D, E and F represent intermediate grade tumors from a single block. Stronger cytoplasmic and weaker nuclear p27 staining is observed. AKT and pAKT staining is more intense. Panels G, H and I represent high grade tumors from a single block. p27 nuclear staining is absent, and AKT and pAKT staining is high intensity.

Table 1.

Nuclear localization of p27 decreases with increasing tumor grade. Cores from 20 patients with 3 blocks each and 3 cores per block were used to record effect of grade on p27 localization. For grade 2 tumors, 43% had nuclear-only staining, whereas none of the grade 4 tumors had nuclear-only staining. C=cytoplasmic only; CN=predominantly cytoplasmic with some nuclear; N=nuclear only; NC=predominantly nuclear with some cytoplasmic.

| P27 localization | Number of samples | Number of samples by tumor grade (%) |

Fitted mixed model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | mean (SD) | p | ||

| C | 21 | 2(4) | 7(12) | 12(23) | 3.40 (0.17) | <0.001 |

| CN | 45 | 1(2) | 19(33) | 25(47) | 3.23 (0.16) | |

| N | 30 | 20(43) | 10(18) | 0(0) | 2.80 (0.16) | |

| NC | 60 | 23(50) | 21(37) | 16(30) | 2.83 (0.15) | |

p27 phosphorylation at T157 Correlates with Localization to the Cytoplasm in RCC Cell Lines

To determine if cytoplasmic sequestration of p27 in RCC was a result of AKT phosphorylation at T157, we first determined if like primary tumors, AKT was active and p27 localized to the cytoplasm in RCC-derived cell lines. p27 was phosphorylated at T157 in all four RCC cell lines examined (Figure 2C), indicating that similar to what was observed in primary RCC and tumor cell explants, phosphorylation of p27 at T157 was a consistent feature of RCC cell lines. As shown in Figure 2C, AKT was phosphorylated (active) in both VHL-negative cell lines 786-O and RCC4 and VHL-positive Caki-1 and ACHN RCC cell lines. The highest levels of AKT phosphorylation were observed in RCC4 and 786-O cells, which also had the highest levels of phosphoS6, indicating that these cell lines also had the highest levels of mTOR signaling, a down-stream effector of AKT.

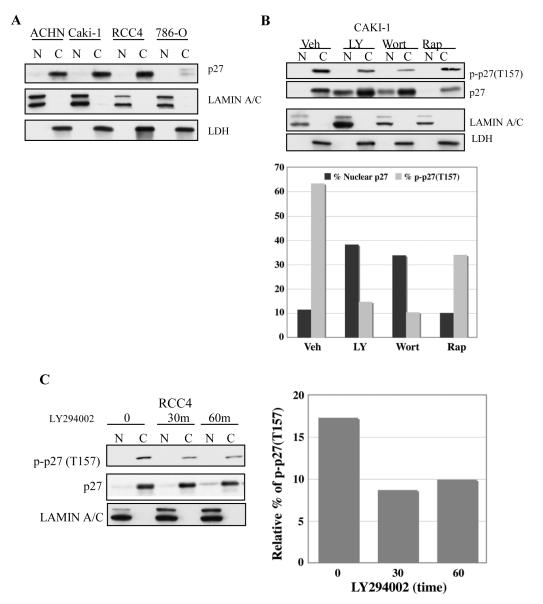

We next examined p27 localization in RCC cell lines. Subcellular fractionation (with lamin A/C and LDH as controls for nuclear or cyoplasmic localization, respectively) revealed that p27 was sequestered in the cytoplasm in these cells (Figure 4A & B). ACHN, Caki-1 and RCC4, expressed abundant p27 that was exclusively cytoplasmic, as did 786-O cells, even though the amount of total p27 expressed by 786-0 cells was lower than the other cell lines (Figures 2C and 4A). Because small proteins such as p27 can leak from the nucleus during subcellular fractionation, cytoplasmic localization of p27 was also confirmed by immunocytochemistry. Endogenous p27 was diffusely localized in RCC cells, with only an occasional cell (<5%) exhibiting strong nuclear immunoreactivity (Figure 4E and data not shown), confirming results obtained by subcellular fractionation demonstrating nuclear exclusion of p27.

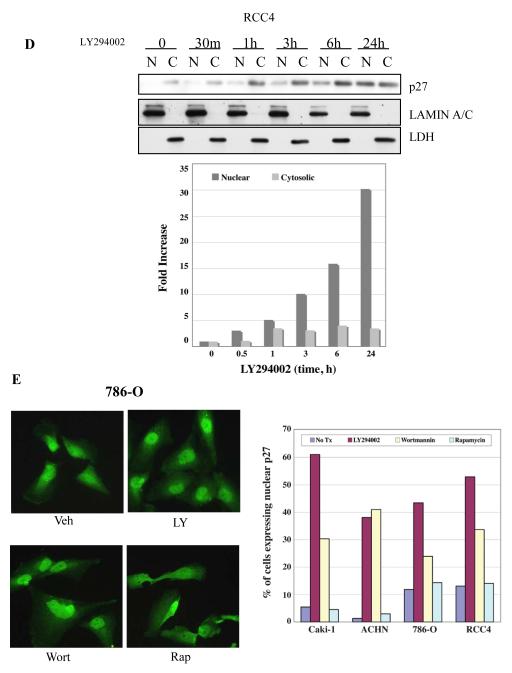

Figure 4. PI3K inhibitors reduce phosphorylation at T157 and restore nuclear localization of p27.

(A) Localization of p27 in RCC cell lines. All cell lines tested exhibit cytoplasmic localization of p27. Lamin A/C and LDH are used as nuclear and cytoplasmic markers, respectively. (B) LY294002 and wortmannin treatment reduce phosphorylation of p27 at T157 and relocalize p27 to the nucleus whereas rapamycin, an mTOR inhibitor, does not. The densitometric analysis done to measure the ratio of nuclear p27 or phosphorylated p27 versus total p27 also confirms that PI3K/AKT inhibition but not mTOR inhibition relocates p27 into nuclei, which correlates with decreased p27 phosphorylation at T157. (C) Phosphorylation of cytoplasmic p27 at Thr157 is rapidly (≤30 min) decreased after LY294002 treatment in RCC4 cells, concomitant with nuclear relocalization of p27. Similar data were obtained with other RCC cell lines (data not shown). (D) Nuclear relocalization of p27 after LY294002 treatment increases as a function of time in RCC4 cells. Similar data were obtained with other RCC cell lines (data not shown). Graph shows that the increase in nuclear p27 is much greater than that of cytoplasmic p27. (E) Immunohistochemistry of p27 showing increased percentage of nuclear staining with PI3K/AKT, but not mTOR inhibition. Graph shows the percentage of cells showing nuclear staining in each treatment group. A single representative experiment (N=2) is shown (>500 cells counted/cell line).

Inhibition of PI3K/AKT but not mTOR Signaling Restores Nuclear Localization of p27

Since phosphorylation of p27 by AKT at T157 has been shown to sequester p27 in the cytoplasm (3-5), we next determined if PI3K/AKT signaling in RCC might be responsible for exclusion of p27 from the nucleus. Although none of the inhibitors altered the cell cycle profile of treated cells at 24 hours (Supplemental Figure 2), as shown in Figure 4B, inhibition of PI3K by the pharmacological inhibitors LY294002 or wortmannin (Supplemental Figure 3) reduced cytoplasmic levels of p27 phosphorylated at T157, while the mTOR inhibitor, rapamycin, had no effect on p27 phosphorylation. Importantly, treatment with PI3K inhibitors that reduced T157 phosphorylation caused a rapid increase in nuclear p27 (Figure 4B, C, & D) which was detectable as early as 30 minutes after treatment with LY294002 or wortmannin (Figures 4C, 4D and data not shown). In addition, while LY294002 and wortmannin increased the total amount of p27 expressed between 1 and 24 hours (Figure 4B & D), densitometric analysis showed that the fold increase of p27 in the nucleus (~30-fold) greatly exceeded that of cytoplasmic p27 (<5-fold) in RCC cells (Figure 4E). Moreover, inhibition of AKT (Supplemental Figure 3) and nuclear relocalization of p27 by PI3K/AKT inhibitors was inversely correlated with levels of p27 phosphorylation at T157 (Figure 4B).

Immunocytochemistry confirmed cellular fractionation data and demonstrated reappearance of p27 in the nucleus of cells treated with either LY294002 or wortmannin. For 786-O, RCC4, Caki-1 and ACHN cells, relocalization of p27 to the nucleus upon PI3K/AKT inhibition was quantitated in response to treatment with these inhibitors. As shown in Figure 4E, treatment with both LY294002 and wortmannin significantly increased p27 localization to the nucleus. In 786-O and RCC4 cells, the percent of cells with nuclear p27 increased from 12% and 13%, respectively, to 42% and 52%, following treatment with LY294002. Wortmannin induced a similar increase in nuclear p27 in treated cells. Caki-1 and ACHN also exhibited relocalization of p27 in the presence of these inhibitors, with LY294002 increasing the percent of Caki-1 cells with nuclear p27 from 5% to 61% and wortmannin also increasing the percent of cells with nuclear p27 to 30%. ACHN cells appeared to be most sensitive to the effect of inhibitor, with LY294002 and wortmannin increasing the percent of cells with nuclear p27 from 2% to 38% and 41%, respectively. Importantly, in contrast to PI3K/AKT inhibitors, the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin had no effect on p27 localization in RCC cells as determined by cell fractionation (Figure 4B) or by immunocytochemistry (Figure 4E). There was no difference in cell cycle distribution of 786-O cells treated with LY294002, wortmannin or rapamycin 24 hrs after treatment (Supplemental Figure 2), demonstrating that differences in p27 localization did not occur as a result of differential induction of cell cycle arrest by these compounds.

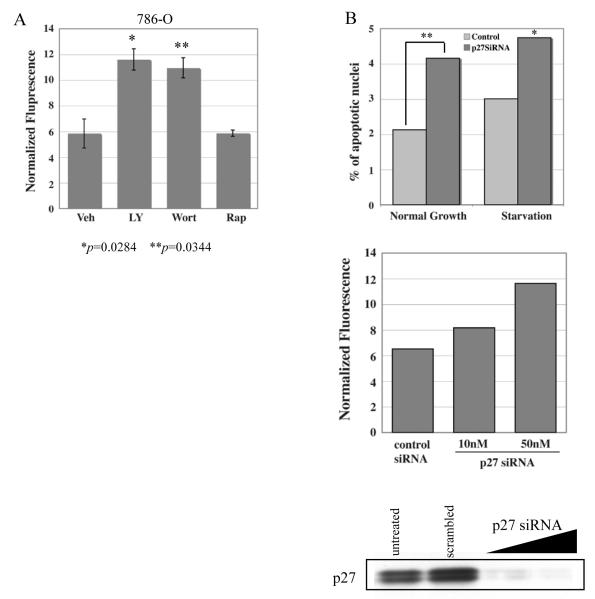

p27 Confers Resistance to Apoptosis in RCC cells

p27 has been reported to exhibit gain-of-function and serve an antiapoptotic role in tumors when phosphorylated and sequestered away from the nucleus (9, 10). To investigate a potential antiapoptotic function for p27 in RCC, we investigated the relationship between cytoplasmic sequestration of p27 out of the nucleus and resistance to apoptosis in RCC cell lines. Treatment of 786-O cells with either LY294002 or Wortmannin (which inhibits AKT and relocalizes p27 to the nucleus, see above) caused a significant increase in apoptosis as assessed by caspase cleavage that was not observed with rapamycin (which does not relocalize p27 to the nucleus) (Figure 5A). Similar results were obtained with Caki-1 cells (data not shown). To demonstrate that p27 was involved in resistance to apoptosis in these cells, siRNA experiments were performed to knockdown p27 in 786-O cells. As shown in Figure 5B, caspase cleavage increased with p27 depletion under both basal and serum-starvation conditions, as did the number of apoptotic nuclei, indicating that p27 directly contributes to resistance to apoptosis in RCC cells.

Figure 5. Cytoplasmic p27 correlates with resistance to apoptosis in RCC cell lines.

(A) Caspase activity (as determined by fluorescence of cleaved caspase substrate) is increased in 786-O cells after 6 hr treatment with either LY294002 (20μM) or wortmannin (200nM), not with rapamycin (2μM). (B) Knockdown of p27 induces caspase activity in 786-O cells. Western blot of p27 verifying siRNA knockdown of p27. Increased apoptosis in p27 siRNA treated 786-O cells is demonstrated by increased apoptotic nuclei (top panel) and increased fluorescence of caspase-cleaved substrate (middle panel).

DISCUSSION

We found that elevated p27 expression and activation of AKT were consistent features of RCC, with cytoplasmic mislocalization of this CKI significantly correlating with higher tumor grade. RCC-derived cell lines, which also exhibited activated AKT and cytoplasmic sequestration of p27, were used to demonstrate that phosphorylation of p27 at T157 of the p27 NLS correlated with cytoplasmic localization and that PI3K inhibitors that inhibited AKT activity reduced T157 phosphorylation and relocalized p27 to the nucleus. Importantly, the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin, which did not decrease AKT activity, was ineffective at reducing p27 phosphorylation at T157 and reversing cytoplasmic mislocalization of p27.

Understanding the role of PI3K/AKT signaling and activation of mTOR in RCC is important, as mTOR inhibitors have shown preclinical efficacy (13) and promise in clinical trials for RCC (19-23), with temsirolimus (Torisel) being recently approved for treatment of advanced RCC. RCC primary tumors and tumor-derived cell lines exhibit activation of PI3K/ AKT signaling (11-13), and while PTEN mutations are rare in RCC, PTEN expression is frequently reduced (14, 15) and decreased PTEN expression is associated with increased AKT activation in RCC (16). While activation of PI3K/AKT and mTOR signaling has been considered in the context of activation of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) in RCC (24), the impact of activation of this signaling pathway on p27 function, and the downstream prognostic and therapeutic implications in RCC, have not been investigated.

AKT is antiapoptotic, directly activating several cell survival pathways, and recently, we and others have shown that under certain conditions, p27 is also antiapoptotic (9, 10). The present study and similar data in rodent models indicates that as a result of activation of kinases that phosphorylate p27, this CKI is sequestered from the nucleus and acquires a gain-of-function antiapoptotic role (25). Thus, it is interesting to speculate that in conjunction with AKT activation, in RCC p27 phosphorylated by this kinase may contribute to cell survival and resistance to drugs that induce apoptosis. Although p27 was not evaluated, Sourbier and colleagues (12) also found that PI3K inhibitors, which we have shown decrease p27 phosphorylation and relocalize it to the nucleus, reduced AKT phosphorylation and induced apoptosis in 786-O cells in vitro. These data suggest the interesting possibility that therapeutics that inhibit AKT and relocalize p27 to the nucleus may have improved therapeutic efficacy over mTOR inhibitors alone (which do not inhibit AKT or relocalize p27 to the nucleus) in patients where p27 contributes to tumor survival.

Prognostic factors for RCC include histological subtype, tumor grade and stage, and clinical characteristics such as performance status, time from diagnosis to systemic therapy, anemia, lactate dehydrogenase levels, and hypercalcemia and location and number of metastases (26-29). As defined by Steeg and Abrams (30), clinical markers must be 1) reproducible 2) provide prognostic information independent from and better than other conventional pathological criteria and 3) provide information that can influence treatment decisions. Currently there are no molecular markers for RCC that meet the College of American Pathologists criteria for use in patient management, or which has sufficient biological or clinical validation for acceptance (31). However, several prognostic and predictive biomarker candidates are in various stages of validation for RCC including PCNA, Ki67, silver staining of nucleolar organizing regions (32-35), molecular markers such as VHL status (36), carbonic anhydrase (37, 38), and PTEN (39), and protein expression profiles (40).

Data that loss of nuclear p27 correlates with tumor grade suggests that p27 expression and/or localization may also be useful biomarker(s) for RCC, warranting further clinical validation. The utility of p27 as a prognostic marker has been validated for many cancers [for a review see (41)], including breast, GI, prostate lung and ovarian cancer. Recently, p27 has received interest as a potential prognostic marker for RCC, although previous studies have generally scored p27 as present or absent rather than its localization within the cell (42-47). Although these data are not altogether concordant, in general the absence of p27 confers a worse prognosis. However, our data suggest that localization may also be important, and that some of the discrepancies in the literature could be attributable to differences between p27-positive tumors where p27 is cytoplasmic (and presumably nonfunctional) versus p27-positive tumors where p27 is nuclear. Interestingly, a recent study examining expression of p27 and Skp2 (the E3 ligase that targets p27 for degradation in the nucleus) found that in general, Skp2 activity increased with stage and grade in clear cell carcinoma while p27 immunoreactivity decreased with stage and grade (46). While this study noted that there was no correlation between p27 and Skp2 expression in individual tumors, as Skp2 would be responsible for degradation of nuclear, but not cytoplasmic p27, additional analysis as to whether p27 expressed in Skp2 positive tumors was in the nucleus versus cytoplasm would likely lend clarity to the interpretation of these data. Importantly, in a recent report from Figlin and colleagues (48), in a series of tissue microarrays 48% of RCCs had cytoplasmic p27 and cytoplasmic localization of p27 was higher in metastatic RCC. In the cohort of patients examined in that study, higher nuclear p27 also predicted a more favorable outcome. Similar to our analysis, these authors also concluded that cytoplasmic mislocalization of p27 is a poor prognostic finding, and possibly an important parameter for patient selection for targeted therapy.

Additionally, upregulation of AKT in primary RCC tumors is associated with poorer outcome (49). This observation underscores the potential prognostic significance of AKT activation in RCC, and is concordant with our hypothesis that part of the phenotype associated with activated AKT is phosphorylation and cytoplasmic mislocalization of p27. Our data suggest that in RCC, AKT pathway inhibition can relocalize p27 to the nucleus, and this effect is VHL-independent. These findings have potential clinical implications in the choice of agents for patients with renal cell carcinoma. Recent data suggest that temsirolimus is relatively more active in patients with papillary versus clear cell renal cell carcinoma (50). It is possible the lack of response in these patients is not due to VHL status per se, but the functional status of p27. Thus, additional studies are warranted to evaluate the impact of p27 status on response and resistance to rapamycin or other targeted therapy in RCC.

In summary, we have shown that in RCC nuclear exclusion of p27 and AKT phosphorylation confers resistance to apoptosis, and preferential sensitivity to AKT inhibition as compared to mTOR inhibition. These data provide important insights regarding the mechanism of p27 mislocalization in RCC, and its potential utility as a predictive biomarker. Furthermore, p27 status may be relevant for choosing tyrosine kinase inhibitors, alone or in combination with mTOR inhibitors in the clinical management of RCC. Additional studies are now warranted to validate these preclinical observations and test these hypotheses in RCC patients treated with targeted agents.

Statement of Translational Relevance.

Currently there are no molecular markers that meet the College of American Pathologists criteria for use in patient management or with sufficient biological or clinical validation for acceptance in renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Data presented in this report that loss of nuclear p27 correlates with tumor grade suggests that p27 expression and localization may be a useful biomarker for RCC, warranting further clinical validation. In addition, mTOR inhibitors have received great attention recently for preclinical efficacy and promise in clinical trials for RCC, and temsirolimus (Torisel) has now been approved for treatment of advanced RRC. However, the fact that PI3K/AKT but not mTOR inhibitors relocalize p27 to the nucleus and induce apoptosis suggests that therapeutics that inhibit PI3K/AKT may have improved therapeutic efficacy over inhibitors that target mTOR alone.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 1: Total and phospho AKT intensity as a function of p27 localization. Intensity was dichotomized into low and high values, and compared to p27 localization. Tumors with exclusive cytoplasmic staining have the highest AKT intensity, with borderline P=0.058. A similar trend seen in tumors stained with phospho AKT, but with nonsignificant p-value. C=cytoplasmic only; CN=predominantly cytoplasmic with some nuclear; N=nuclear only; NC=predominantly nuclear with some cytoplasmic stain.

Supplemental Figure 1. Control TMA cores to show specificity in pAKT staining. Cores taken from the same TMA showing normal kidney in A), very low staining in a low grade RCC in B) and high level stain in a high grade sample in C).

Supplemental Figure 2. Cell cycle analysis of 786-O treated with LY294002, wortmannin, and rapamycin for 24 hours.

Supplemental Figure 3. Treatment of 786-O cells with LY, wortmannin, rapamycin demonstrates that all three drugs inhibit mTOR signaling (phosphoS6=PS6) but only LY294002 and wortmannin inhibit AKT (phosphoAKT=pAKT).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Center for Research on Environmental Disease with funding from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (P30 ES007784), the James and Esther King Biomedical Research Program of The Florida Department of Health (JAC), Dr. and Mrs. Ellis Brunton Rare Cancer Research Fund (JAC), funding from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grants R01CA104505 (JAC and CGW) and R01 CA63613 (CLW) and Child Health and Human Development grant R01 HD046282 (CLW). The expertise in immunohistochemistry of Brandy Edenfield (MCJ) is much appreciated.

References

- 1.Slingerland J, Pagano M. Regulation of the cdk inhibitor p27 and its deregulation in cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2000;183:10–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200004)183:1<10::AID-JCP2>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloom J, Pagano M. Deregulated degradation of the cdk inhibitor p27 and malignant transformation. Semin Cancer Biol. 2003;13:41–7. doi: 10.1016/s1044-579x(02)00098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viglietto G, Motti ML, Fusco A. Understanding p27(kip1) deregulation in cancer: down-regulation or mislocalization. Cell Cycle. 2002;1:394–400. doi: 10.4161/cc.1.6.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coqueret O. New roles for p21 and p27 cell-cycle inhibitors: a function for each cell compartment? Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:65–70. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)00043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hengst L. A second RING to destroy p27(Kip1) Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1153–5. doi: 10.1038/ncb1204-1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin I, Yakes FM, Rojo F, et al. PKB/Akt mediates cell-cycle progression by phosphorylation of p27(Kip1) at threonine 157 and modulation of its cellular localization. Nat Med. 2002;8:1145–52. doi: 10.1038/nm759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viglietto G, Motti ML, Bruni P, et al. Cytoplasmic relocalization and inhibition of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27(Kip1) by PKB/Akt-mediated phosphorylation in breast cancer. Nat Med. 2002;8:1136–44. doi: 10.1038/nm762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang J, Zubovitz J, Petrocelli T, et al. PKB/Akt phosphorylates p27, impairs nuclear import of p27 and opposes p27-mediated G1 arrest. Nat Med. 2002;8:1153–60. doi: 10.1038/nm761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu FY, Wang SE, Sanders ME, et al. Reduction of cytosolic p27(Kip1) inhibits cancer cell motility, survival, and tumorigenicity. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2162–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang J, Shao SH, Xu ZX, et al. The energy sensing LKB1-AMPK pathway regulates p27(kip1) phosphorylation mediating the decision to enter autophagy or apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:218–24. doi: 10.1038/ncb1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robb VA, Karbowniczek M, Klein-Szanto AJ, Henske EP. Activation of the mTOR signaling pathway in renal clear cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2007;177:346–52. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.08.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sourbier C, Lindner V, Lang H, et al. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway: a new target in human renal cell carcinoma therapy. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5130–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gemmill RM, Zhou M, Costa L, Korch C, Bukowski RM, Drabkin HA. Synergistic growth inhibition by Iressa and Rapamycin is modulated by VHL mutations in renal cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:2266–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brenner W, Farber G, Herget T, Lehr HA, Hengstler JG, Thuroff JW. Loss of tumor suppressor protein PTEN during renal carcinogenesis. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:53–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Velickovic M, Delahunt B, McIver B, Grebe SK. Intragenic PTEN/MMAC1 loss of heterozygosity in conventional (clear-cell) renal cell carcinoma is associated with poor patient prognosis. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:479–85. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hara S, Oya M, Mizuno R, Horiguchi A, Marumo K, Murai M. Akt activation in renal cell carcinoma: contribution of a decreased PTEN expression and the induction of apoptosis by an Akt inhibitor. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:928–33. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cai SL, Tee AR, Short JD, et al. Activity of TSC2 is inhibited by AKT-mediated phosphorylation and membrane partitioning. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:279–89. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal Data Analysis using Generalized Linear Models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atkins MB, Hidalgo M, Stadler WM, et al. Randomized phase II study of multiple dose levels of CCI-779, a novel mammalian target of rapamycin kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced refractory renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:909–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raymond E, Alexandre J, Faivre S, et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of escalated doses of weekly intravenous infusion of CCI-779, a novel mTOR inhibitor, in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2336–47. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Motzer RJ, Michaelson MD, Redman BG, et al. Activity of SU11248, a multitargeted inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor, in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:16–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho D, Signoretti S, Regan M, Mier JW, Atkins MB. The role of mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors in the treatment of advanced renal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:758s–63s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2271–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas GV, Tran C, Mellinghoff IK, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor determines sensitivity to inhibitors of mTOR in kidney cancer. Nat Med. 2006;12:122–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Short J, Houston K, Dere R, et al. AMPK Signaling Directs p27KIP1 to the Cytoplasm via Phosphorylation at T170. 2008. In Press.

- 26.Elson PJ, Witte RS, Trump DL. Prognostic factors for survival in patients with recurrent or metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1988;48:7310–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Motzer RJ, Mazumdar M, Bacik J, Berg W, Amsterdam A, Ferrara J. Survival and prognostic stratification of 670 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2530–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mekhail TM, Abou-Jawde RM, Boumerhi G, et al. Validation and extension of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering prognostic factors model for survival in patients with previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:832–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Schwartz LH, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in previously treated patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:454–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steeg PS, Abrams JS. Cancer prognostics: past, present and p27. Nat Med. 1997;3:152–4. doi: 10.1038/nm0297-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gelb AB. Renal cell carcinoma: current prognostic factors. Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer. 1997;80:981–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sejima T, Miyagawa I. Expression of bcl-2, p53 oncoprotein, and proliferating cell nuclear antigen in renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 1999;35:242–8. doi: 10.1159/000019855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aaltomaa S, Lipponen P, Ala-Opas M, Eskelinen M, Syrjanen K. Prognostic value of Ki-67 expression in renal cell carcinomas. Eur Urol. 1997;31:350–5. doi: 10.1159/000474482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yasunaga Y, Shin M, Miki T, Okuyama A, Aozasa K. Prognostic factors of renal cell carcinoma: a multivariate analysis. J Surg Oncol. 1998;68:11–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199805)68:1<11::aid-jso4>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delahunt B, Ribas JL, Nacey JN, Bethwaite PB. Nucleolar organizer regions and prognosis in renal cell carcinoma. J Pathol. 1991;163:31–7. doi: 10.1002/path.1711630107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yao M, Yoshida M, Kishida T, et al. VHL tumor suppressor gene alterations associated with good prognosis in sporadic clear-cell renal carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1569–75. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.20.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bui MH, Seligson D, Han KR, et al. Carbonic anhydrase IX is an independent predictor of survival in advanced renal clear cell carcinoma: implications for prognosis and therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:802–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Atkins M, Regan M, McDermott D, et al. Carbonic anhydrase IX expression predicts outcome of interleukin 2 therapy for renal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3714–21. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim HL, Seligson D, Liu X, et al. Using tumor markers to predict the survival of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2005;173:1496–501. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154351.37249.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lam JS, Pantuck AJ, Belldegrun AS, Figlin RA. Protein expression profiles in renal cell carcinoma: staging, prognosis, and patient selection for clinical trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:703s–8s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belletti B, Nicoloso MS, Schiappacassi M, et al. p27(kip1) functional regulation in human cancer: a potential target for therapeutic designs. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:1589–605. doi: 10.2174/0929867054367149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anastasiadis AG, Calvo-Sanchez D, Franke KH, et al. p27KIP1-expression in human renal cell cancers: implications for clinical outcome. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:217–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haitel A, Wiener HG, Neudert B, Marberger M, Susani M. Expression of the cell cycle proteins p21, p27, and pRb in clear cell renal cell carcinoma and their prognostic significance. Urology. 2001;58:477–81. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hedberg Y, Davoodi E, Ljungberg B, Roos G, Landberg G. Cyclin E and p27 protein content in human renal cell carcinoma: clinical outcome and associations with cyclin D. Int J Cancer. 2002;102:601–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hedberg Y, Ljungberg B, Roos G, Landberg G. Expression of cyclin D1, D3, E, and p27 in human renal cell carcinoma analysed by tissue microarray. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:1417–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Langner C, von Wasielewski R, Ratschek M, Rehak P, Zigeuner R. Biological significance of p27 and Skp2 expression in renal cell carcinoma. A systematic analysis of primary and metastatic tumour tissues using a tissue microarray technique. Virchows Arch. 2004;445:631–6. doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-1121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Migita T, Oda Y, Naito S, Tsuneyoshi M. Low expression of p27(Kip1) is associated with tumor size and poor prognosis in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:973–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pantuck AJ, Seligson DB, Klatte T, et al. Prognostic relevance of the mTOR pathway in renal cell carcinoma: implications for molecular patient selection for targeted therapy. Cancer. 2007;109:2257–67. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Horiguchi A, Oya M, Uchida A, Marumo K, Murai M. Elevated Akt activation and its impact on clinicopathological features of renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2003;169:710–3. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000038952.59355.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dutcher JP, Szczylik C, Tannir N, et al. ASCO; 2007. Correlation of survival with tumor histology, age, and prognostic risk group for previously untreated patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (adv RCC) receiving temsirolimus (TEMSR) or interferon-alpha (IFN) p. 5033. 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 1: Total and phospho AKT intensity as a function of p27 localization. Intensity was dichotomized into low and high values, and compared to p27 localization. Tumors with exclusive cytoplasmic staining have the highest AKT intensity, with borderline P=0.058. A similar trend seen in tumors stained with phospho AKT, but with nonsignificant p-value. C=cytoplasmic only; CN=predominantly cytoplasmic with some nuclear; N=nuclear only; NC=predominantly nuclear with some cytoplasmic stain.

Supplemental Figure 1. Control TMA cores to show specificity in pAKT staining. Cores taken from the same TMA showing normal kidney in A), very low staining in a low grade RCC in B) and high level stain in a high grade sample in C).

Supplemental Figure 2. Cell cycle analysis of 786-O treated with LY294002, wortmannin, and rapamycin for 24 hours.

Supplemental Figure 3. Treatment of 786-O cells with LY, wortmannin, rapamycin demonstrates that all three drugs inhibit mTOR signaling (phosphoS6=PS6) but only LY294002 and wortmannin inhibit AKT (phosphoAKT=pAKT).