Abstract

Traumatic ruptures of the diaphragm occur after blunt or penetrating thoracoabdominal injuries and are one of the most overlooked conditions. Although the risk of death due to rupture per se is low, when left undiagnosed this condition may cause serious complications and death due to gastrointestinal herniation. In this report, a patient with traumatic rupture of the diaphragm who presented with signs of intestinal obstruction is reported. The rupture occurred as a result of an abdominal penetrating injury sustained 3 years ago, and was not diagnosed during the acute phase of injury.

BACKGROUND

Traumatic diaphragmatic rupture (TDR) is a very rare entity seen in 3–7% of all thoracoabdominal injuries. The condition is missed during the acute phase in 12–60% of post-traumatic asymptomatic TDR cases. Gastrointestinal herniations in these individuals result in significant complications and death.1

This report presents a patient with delayed traumatic diaphragmatic rupture diagnosed 3 years after trauma, and who can therefore be classified into the obstructive group.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 21-year-old man presented to the emergency department with abdominal distension and pain, neausea, vomiting and failure to pass gas and stool. In physical examination, the blood pressure and pulse were 110/60 mmHg and 88/min, respectively. The abdomen was distended and there were no palpable masses. Bowel sounds were hyperactive on auscultation. There were no hernias on examination of the inguinal regions. The haemogram and biochemical values were normal. Upright abdominal x ray showed multiple air fluid levels and elevation of the left diaphragm (fig 1). Past medical history of the patient revealed that 3 years previously he had sustained a penetrating injury to his thorax at the seventh intercostal space along the anterior axillary line. He was then hospitalised for 10 days and later discharged without having surgery.

Figure 1.

Upright abdominal x rays show multiple air fluid levels and elevation of left diaphragm.

The patient was diagnosed with intestinal obstruction and hospitalised. Oral intake was discontinued, and nasogastric decompression and intravenous infusion of balanced solution were initiated. At the end of a 36 h observation period there was still no passage of gas and stool. Air fluid levels persisted on upright abdominal x ray. The patient was taken to the operating room with the possible diagnosis of intestinal obstruction. Exploration revealed that the major omentum and splenic flexure of the colon herniated into the left hemithorax through a rupture in the diaphragm and resulted in intestinal obstruction. The omentum and colon were detached from the adhesions and taken back into the abdominal cavity. The diaphragmatic rupture, measuring 5 cm in diameter (fig 2), was repaired with no. 1 prolene sutures. A thoracic tube was inserted to the left chest. The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient was seen 1 year after the operation. There were no abnormalities in physical examination, chest x ray and abdominal CT

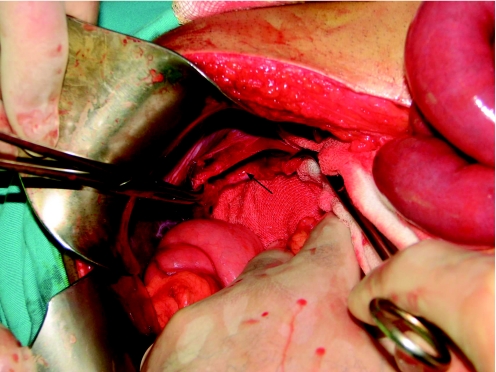

Figure 2.

Rupture in the diaphragm resulted in intestinal obstruction.

DISCUSSION

The majority of blunt and penetrating injuries involve the thoracoabdominal areas. The intra-abdominal pressure that increases after blunt trauma can result in diaphragmatic injury or organ herniation. In a penetrating injury of the upper abdomen and lower thorax, such as a gunshot wound and a stab wound, possible diaphragmatic injury should be kept in mind. The left hemidiaphragm is more commonly involved in this type of trauma. This is presumably due to the fact that most people are right handed. In our case, also, left hemidiaphragm injury was seen after penetrating thoracoabdominal trauma.

Diaphragmatic injuries are classified into three groups according to the time of diagnosis: acute, latent and chronic (obstructive). The acute group includes cases diagnosed within the first 2 weeks after injury, the latent group includes cases diagnosed before the development of strangulation in organs herniated after injury. The latent phase, which is the asymptomatic period following trauma, may last between 20 days and 28 years (mean 4.1 years). The most frequent symptom during this phase is pain. TDR may impair diaphragmatic function and result in respiratory disturbances. This phase is frequently accompanied by dyspnoea. There were no respiratory problems in our case during the latent phase. The obstructive group includes cases who are diagnosed after complications due to strangulation have developed.2 The diagnosis in the case presented was made 3 years after trauma when the symptom of the intestinal obstruction occurred.

Shah et al made a review of 20 studies including 980 patients, and reported that 43.5% of diaphragm ruptures were diagnosed preoperatively, 41.4% were diagnosed during surgery or autopsy, and in 14.6% of cases the diagnosis was delayed.2 If there are no injuries in the organs neighbouring the diaphragm, conservative management may delay the diagnosis of TDR. Therefore it should be kept in mind that patients with thoracoabdominal injury may have associated diaphragmatic rupture and, when such patients are managed conservatively, repeated radiological studies focusing on the diaphragm should be used. In conservative management, if an abnormal finding on the right hemidiaphragm is seen on chest x ray, CT and observation are necessary. If there is an abnormal finding on the left hemidiaphragm, laparoscopy and thoracoscopy should be performed. In this way, delays in the diagnosis of TDR can be reduced.3

Non-invasive techniques, including x rays of the chest and abdomen, barium x rays, CT and MRI, or invasive techniques, including laparoscopy and thoracoscopy, can be used for the diagnosis of diaphragmatic rupture.4–8 Eren et al described an algorithm for the choice of imaging techniques after TDR and suggested a multidisciplinary approach.4 According to Eren et al, x rays should be the first choice although establishing the diagnosis is not always possible.Plain chest x ray studies or abdominal films will often show an elevated or irregular outline of the hemidiaphragm. Repeated imaging studies increase the probability of establishing a diagnosis. Doppler ultrasonography and CT are especially helpful in acute injuries. In selected patients, the MRI allows better evaluation of the diaphragm. It has been reported that the passage of abdominal organs can be traced using the valsalva manoeuvre in cases with a silent clinical picture. These radiological studies can reveal loss of integrity of the diaphragm, presence of intestinal gas in thorax, atelectasis and hydro/pneumothorax. In the present case, chest x rays obtained during the acute phase and at the time of presentation did not reveal presence of intestinal gas within the thorax. However, there were no changes in colonic gas shadows and these shadows remained in the same location, suggesting a suspension from the diaphragm; elevation of the diaphragm was also evident.

A combination of these findings with a history of lower thoracic injury may suggest diaphragmatic injury. When TDR is suspected during acute or latent phase, minimal invasive techniques such as laparoscopy and thoracoscopy can be used for diagnosis. Thoracoscopy can also be used for therapeutic purposes.7,8

LEARNING POINTS

Post-traumatic asymptomatic traumatic diaphragmatic rupture cases may go unnoticed and present with gastrointestinal herniation or obstruction.

The increased preference of conservative approach in the follow-up of blunt and penetrating abdominal traumas may result in the failure to diagnose isolated diaphragmatic ruptures.

Radiological studies including chest x ray, ultrasound and CT in such individuals should be evaluated with this possibility in mind. In the latent phase, these studies can be supplemented with minimal invasive techniques such as laparoscopy or thoracoscopy.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Reina A, Vidana E, Soriano P, et al. Traumatic intrapericardial diaphragmatic hernia: case report and literature review. Injury 2001; 32: 153–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah R, Sabanathan S, Mearns AJ, et al. Traumatic rupture of diaphragm. Ann Thorac Surg 1995; 60: 1444–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asensio JA, Demetriades D, Rodriguez A. Injury to the diaphragm. : Mattox KL, Feliciano DV, Moore EE, eds. Trauma. 4th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000: 603–32 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eren S, Kantarcı M, Okur A. Imaging of diaphragmatic rupture after trauma. Clin Radiol 2006; 61: 467–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Killen KL, Mirvis SE, Shanmuganathan K. Helical CT of diaphragmatic rupture caused by blunt trauma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1999; 173: 1611–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pace ME, Krebs TL. MR. imaging of the thoracoabdominal junction. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2000; 8: 143–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer G, Huttl TP, Hatz RA, et al. Laparoscopic repair of traumatic diaphragmatic hernias. Surg Endosc 2000; 14: 1010–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kocher TM, Gürke L, Kuhrmeier A, et al. Misleading symptoms after a minor blunt chest trauma: thoracoscopic treatment diaphragmatic rupture. Surg Endosc 1998; 12: 879–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]