Abstract

Hypercalcaemia in infants with Down syndrome is an uncommon condition with only five previous case reports. The patients often present in the toddler years with the classical triad of Down syndrome, biochemical hypercalcaemia, and nephrocalcinosis. We present the sixth case and second male with this condition and further review the clinical details of this under-recognised condition and stratify the diagnostic criteria. The management mandates a reduction in calcium intake as a first step. The natural history of the various aspects of this condition is also considered.

BACKGROUND

Hypercalcaemia in infants with Down syndrome is an uncommon condition with only five previous case reports. The patients often present in the toddler years with the classical triad of Down syndrome, biochemical hypercalcaemia and nephrocalcinosis. We report the sixth case of this unusual condition and make a complete review of the available case reports and propose the diagnostic criteria. Recognition of the condition is critical in the management which mandates a reduction in calcium intake as a first step.

CASE PRESENTATION

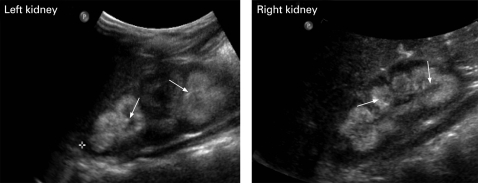

A 24-month-old male infant with Down syndrome presented with progressive failure to thrive. His pregnancy was full term and delivery was uneventful from non-consanguineous parents. No other related complications were present. Despite the Down syndrome, his postnatal progress was satisfactory until the current presentation when he developed a cough, mild anorexia and progressive weight loss. No other symptom was present on system review; there was no history of food or egg allergy. His general dietary intake was mainly solid, assessed to contain ∼200 mg daily. In addition, he was fed ∼500 ml of regular milk daily, totalling ∼500 mg of calcium. There was no over the counter or unprescribed calcium supplements. General examination showed an active and otherwise well child with typical Down syndrome clinical features. His weight was 8.64 kg (in the 20th centile) and height 78 cm (25th centile) using growth chart for boys with Down syndrome (0–3 years). He was in the 50th centile six months earlier. No other abnormalities were detected. His formula feed was increased by 20% with no improvement. In fact, he became more anorectic and began to vomit, worse after he was fed an omelette (mixed with full cream milk). He continued to lose weight, to <8.4 kg at 4 month follow-up (below the 5th centile at 28 months). At that time, the patient appeared lean with palpable faecal masses despite a satisfactory hydration status, with normal tissue turgor and pulse rate. His initial renal function tests, angiotensin conversion enzyme activity, serum cortisol, adrenocorticotropic hormone, thyrotropin and tetra-iodothyronine values were normal. Results of the calcitropic investigations are listed in table 1, and the renal ultrasound results are shown in fig 1. In addition, his plain chest x ray, computed tomography of his chest, and a bone scan were normal, excluding sarcoidosis as an alternative cause of hypercalcaemia, especially in the presence of a cough. His parents’ mineral status were assessed to be satisfactory with normal calcitropic hormonal profiles, including 25-hydroxyvitamin D (not shown).

Table 1.

The initial and subsequent calcitropic biochemical responses to dietary manipulation

| At presentation | After calcium restriction | |

| Age (months) | 24 | 40 |

| Calcium (2.20–2.60 mmol/l) | 3.00 | 2.49 |

| Phosphate (1.05–1.80 mmol/l) | 1.56 | 1.40 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 126 (75–383 U/l)* | 236 (86–315 U/l)* |

| Parathyroid hormone (0.8–8.0 pmol/l) | 0.4 | 35 |

| 25-hydroxyvitamin D (>50 nmol/l indicates sufficiency; 25–50 insufficiency, 12.5–24 moderate deficiency, <12.5 severe deficiency)1 | 72 | 51 |

| 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (38–162 pmol/l) | Undetectable | N/A |

| Urinary calcium excretion (<1.25 mmol/l)* | 3.68 | 1.50 |

| Urinary calcium/creatinine ratio (0.07–1.40)* | 1.74 | 0.76 |

| Weight (kg) | 8.41 | 11.8 |

| Centile | <5th | ∼25th |

N/A, not available.

Reference intervals (RIs) are in parentheses; *denotes age related RIs.

Figure 1.

Bilateral nephrocalcinosis (arrows) as demonstrated on ultrasonography.

The diagnosis of ABCD syndrome was made (see below) and the patient was started on a low calcium diet. His milk was substituted with Locasol with a calcium content <7 mg/l. His progress was very satisfactory with increasing appetite, resolution of the anorexia and constipation. Eight weeks later, he became normocalcaemic with a serum calcium of 2.45 mmol/l. Locasol was continued and he was gradually allowed unrestricted solid diet. At 39 months, his progress was satisfactory with a weight of 11.1 kg at the 25th centile.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

At 60 months, his weight was 18.2 kg (35th centile) and there had been no further episodes of hypercalcaemia.

DISCUSSION

The A, B, C, D syndrome is a tetrad of AB-normal Calcium, Calcinosis, Creatinine in Down syndrome. This syndrome is often under-recognised and thus undetected, despite the Down syndrome prevalence of ∼1 per 1000 live births. The condition is uncommon with only five previous case reports worldwide thus far, including four females and one male.2–6 Ours is the sixth, and second in a male, giving a female preponderance of 2:1.

Hypercalcaemia is the cornerstone of the diagnosis in the right clinical setting and typically develops spontaneously in early infancy. Failure to thrive is the most common presenting symptom. Symptoms are non-specific but those related to hypercalcaemia should be specifically sought. The mechanism of hypercalcaemia is sketchy so far but is thought to be related to an increase in intestinal absorption of the calcium.6 It is, however, useful to speculate on the calcium homeostasis in this situation. Chromosome 21 carries no gene definitively involved in the regulation of calcium, but of significant note is the recent discovery of the “transient receptor potential” or TRP channels. These channels regulate calcium homeostasis both extra- and intracellularly and may contribute to the pathogenesis of a number of medical diseases. The TRP channels consist of seven subfamilies of which the relevant ones to the ABCD syndrome are the TRP-V (vanilloid) and TRP-M (melastatin).7 The TRP-M2 is located on chromosome 21 and has been implicated in the development of leukaemia, a common fatal complication of Down syndrome, but not so much in the development of hypercalcaemia. TRP-M3to8 and TRP-V5to6 are proposed to be heavily involved in calcium and magnesium metabolism at the small intestine, duodenal and renal levels.8,9 None of these channels is located on chromosome 21, however. Additionally, the effect of an extraneous 21 chromosome on the function of the TRP channels remains unknown.

Whatever the mechanism may be, the hypercalcaemia responds to the restriction of calcium intake, commonly with the use of Locasol where the calcium is very low (<7 mg/l). Furthermore, the syndrome should be recognised early as a supplementary diet high in calcium can inadvertently exacerbate the hypercalcaemia, much to the detriment of the patient. This is a possible reason for our patient’s deterioration after he was fed an omelette which, if made up with whole milk, would contain ∼250 mg of elemental calcium. Although not demonstrated biochemically, the symptoms appeared consistent with hypercalcaemia at the time and may indeed represent a physiological calcium loading test. Although highly relevant and pertinent in furthering the understanding of this condition,10,11 this test may similarly exacerbate the hypercalcaemia, especially where other comorbidities may be present. One previous study reported an increase in the urinary calcium/creatinine ratio without systemic hypercalcaemia,4 however. It is noteworthy that the calcium homeostatic mechanism has matured as early as 10 months of age6 with appropriate and physiological suppression of the calcitropic hormones, parathyroid hormone (PTH) and 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D. This is well demonstrated in our case. Another possible underlying mechanism is the increased sensitivity to 25-hydroxyvitamin D rather than the actual level, although all cases report satisfactory levels without being toxic.12 Prognostically, the hypercalcaemia responds well to calcium intake restriction and appears to resolve with maturity when mixed solid diet is introduced as illustrated in our case. Additionally, it is important that alternative causes of hypercalcaemia are fully excluded. Down syndrome is prone to the development of hypothyroidism which in turn can result in hypercalcaemia, but this has been excluded in our case. Table 2 summarises all the relevant features in all the reported cases so far.

Table 2.

Presenting features of the reported cases of hypercalcaemia associated with Down syndrome

| Cases | Gender | Chromosomal abnormality | Age at presentation (months) | Creatinine (Cr) (μmol/l) | Calcium (Ca) (mmol/l) | Vitamin D (nmol/l) | Urinary Ca/Cr ratio | Medullary nephrocalcinosis | Pretreatment dietary calcium content (mg/day) |

| Case 12 | Female (full term) | 47XX | 33 | 100 | 3.25 | 27.5 | 2.24 | Yes | N/A |

| Case 23 | Female (full term) | 47XX | 18 | 88.4 | 3.60 | 82.5 | 1.11 | Yes | N/A |

| Case 34 | Female (not stated) | 47XX | 15 | 35.3 | 2.75 | N/A | 1.84 | Yes | 660 mg |

| Case 45 | Female (33 weeks) | 47XX | 48 | 144 | 3.35 | 133.0 | 2.03 | Yes | 830 mg |

| Case 56 | Male (not stated) | 47XY | 10 | 61 | 1.79 (ionised Ca++) | 78.0 | 2.05 | Yes | 650 mg |

| Current case | Male (full term) | 47XY | 24 | 45.0 | 3.00 | 72.0 | 1.74 | Yes | N/A |

N/A, not available.

All cases present with failure to thrive with pronounced decrease in weight to <5th centile. Serum parathyroid hormone and 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D values are all appropriately suppressed. The recommended daily calcium intake for this age group is 500 mg (12.5 mmol). Please refer to table 1 for the relevant reference intervals (RIs).

The nephrocalcinosis also appears universal (table 2). The mechanism is again not fully understood but it must represent calcium crystallisation in the chronic hypercalciuric milieu. This indicates that the hypercalciuria must have been present for some time before the diagnosis is made. The condition is not uncommon in preterm infants although one patient5 did not suffer a stormy course as a result of prematurity and was not exposed to loop diuretic. This patient had been relatively well until the onset of illness. The calcinosis appears permanent, at least at the completion of the respective reports, and the longer natural history remains unknown so far. Nephrocalcinosis may in turn lead to renal impairment that is prevalent of this condition. Elevated creatinine is common but not in our patient (table 2), perhaps due to the early timing of the diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Formal glomerular filtration rate (GFR) assessment was impractical and not performed. Estimated GFR in children using cystatin C (CysC) based prediction equations has merits although CysC measurement is not routinely available.13 This is despite the presence of nephrocalcinosis, which appears to precede the development of renal impairment in our case and may indicate the sensitivity of the renal tissue to the hypercalcaemia without necessarily affecting the nephron function. This observation must be tempered against the fact that the prevalence of nephrocalcinosis in otherwise normocalcaemia Down syndrome cases is not known. Similarly, the natural history of the hypercalcaemic aspect of this syndrome is unknown. Fortunately, and despite the fact that nephrocalcinosis appears permanent, the high creatinine concentration often improves with the restoration to normocalcaemia and presumably general hydration state. The suggested diagnostic criteria for this syndrome are listed in table 3.

Table 3.

Proposed diagnostic criteria for the ABCD syndrome

| Major criteria | Minor criteria |

|

Reduced glomerular filtration rate |

|

<48 months of age at presentation |

|

|

|

The ABCD syndrome is under-recognised and subsequently under-diagnosed. It is important that this is known so that the correct management strategy can be applied. The prognosis is favourable for both the AB-normal calcaemia and creatinine, although the outcome for calcinosis is inconclusive but appears permanent. This is the only the sixth case and the second in a male infant with this syndrome.

LEARNING POINTS

The hypercalcaemia of Down syndrome (or ABCD syndrome) is a rare and under-recognised condition.

The syndrome classically consists of a tetrad of hypercalcaemia, Down syndrome, renal impairment and nephrocalcinosis.

The condition responds well to dietary calcium restriction.

The natural history is unknown but appears to resolve with time.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anon Vitamin D and adult bone health in Australia and New Zealand: a position statement. Med J Aust 2005; 182: 281–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Proesmans W, De Cock P, Eyskens B. A toddler with Down syndrome, hypercalcaemia, hypercalciuria, medullary nephrocalcinosis and renal failure. Pediatr Nephrol 1995; 9: 112–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreoli SP, Revkees S, Bull M. Hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, medullary nephrocalcinosis, and renal insufficiency in a toddler with Down syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 1995; 9: 673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cobenas C, Spirzzirri F, Zanetta D. Another toddler with Down syndrome, nephrocalcinosis, hypercalcaemia, and hypercalciuria. Pediatr Nephrol 1998; 12: 432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramage IJ, Durkan A, Walker K, et al. Hypercalcaemia in association with trisomy 21 (Down’s syndrome). J Clin Pathol 2002; 55: 543–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filler G, Kotecha S, Milanska J, et al. Trisomy 21 with hypercalcaemia, hypecalciuria, medullary calcinosis and renal failure – a syndrome? Pediatr Nephrol 2001; 16: 99–100 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nilius B, Owsianik G, Voets T, et al. Transient receptor potential cation channels in disease. Physiol Rev 2007; 87: 165–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schlingmann KP, Weber S, Peters M, et al. Hypomagnesemia with secondary hypocalcemia is caused by mutations in TRPM6, a new member of the TRPM gene family. Nat Genet 2002; 31: 166–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmitz C, Perraud AL, Johnson CO, et al. Regulation of vertebrate cellular Mg2+ homeostasis by TRPM7. Cell 2003; 114: 191–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proesmans W. Hypercalcaemia, hypercalciuria and nephrocalcinosis in Down syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 1996; 10: 543–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manz F. A toddler with Down syndrome, hypercalcaemia, hypercalciuria, medullary nephrocalcinosis and renal failure [letter]. Pediatr Nephrol 1996; 10: 251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tau C, Garabedian M, Farriaux JP, et al. Hypercalcaemia in infants with congenital hypothyroidism and its relation to vitamin D and thyroid hormones. J Pediatr 1986; 109: 808–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zappitelli M, Parvex P, Joseph L, Paradis G, Grey V, Lau S, Bell L. Derivation and validation of cystatin C-based prediction equations for GFR in children. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 48: 221–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]