Abstract

A 30-year-old woman presented to the orbital clinic with a 4-year history of a mass in her left upper eyelid of unknown aetiology. Eyelid eversion revealed an embedded hard contact lens, which was removed under local anaesthesia. The patient made a full recovery but this case highlights the need for a careful history in contact lens wearers and a full examination including double eversion of the upper eyelids.

Background

Although the majority of contact lens wearers use soft contact lenses, a significant minority still use hard contact lenses, which are prone to more complications. Lost contact lenses are common and although usually they drop out of the eye, occasionally they migrate into the eyelid fornices where they can become embedded into the eyelid tissue and even migrate into the orbit. They are often asymptomatic because hard contact lenses are made of an inert material and do not cause an inflammatory reaction. When the patient presents some years later, the embedded contact lens can masquerade as a tumour or orbital inflammation and detailed history and examination is vital to avoid unnecessary investigations and surgery.

Case presentation

Our patient was referred to the orbital clinic by her optometrist having seen other healthcare professionals with a 4-year history of a left anterior orbital mass. There was no history of trauma or any other ocular history of note. She was otherwise fit and well.

On examination, visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes corrected with hard contact lenses. There was neither ptosis nor proptosis and ocular motility was full without diplopia. Both eyes were white and quiet and intraocular examination was unremarkable. A mass was noted in the left anterosuperior orbit, which was firm and not tender on palpation (fig 1). The patient denied that the mass changed in size or caused any discomfort.

Figure 1.

The patient at presentation with a subtle left upper eyelid mass, only discernible on inspection when the patient had her eyes closed.

Eversion of the left upper eyelid revealed mild conjunctival redness and papillae with a pale circular mass visible on the palpebral aspect of the conjunctiva consistent with an embedded hard contact lens (fig 2). Further questioning revealed that she had indeed lost a contact lens several years ago, but she had assumed it had fallen out of her eye.

Figure 2.

Eversion of the left upper eyelid revealed a circular lesion consistent with an embedded hard contact lens.

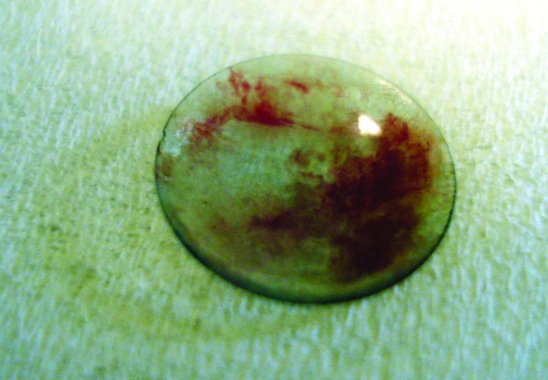

The left upper eyelid was explored under local anaesthesia and a hard contact lens was removed (fig 3). She made a full recovery.

Figure 3.

The hard contact lens following surgical removal.

Investigations

Hard contact lens cannot be seen using standard x rays but ultrasound, CT scanning or MRI may be of use to identify the foreign body.

Differential diagnosis

Preseptal or orbital cellulitis, orbital abscess, orbital inflammation, orbital tumour (primary or secondary), dermoid or epidermoid cyst, lymphoma, orbital varix, retained foreign body following trauma and thyroid eye disease.

Treatment

The left upper eyelid was explored under local anaesthesia and a hard contact lens was removed (fig 3).

Outcome and follow-up

The patient made a full recovery.

Discussion

Although soft contact lenses are now far more popular than hard lenses, there are many people who still wear them without issue on a daily basis. The loss of a contact lens is a common occurrence, usually out of the eye but sometimes into the conjunctival fornices; erosion into the surrounding soft tissues is rare and can present in different ways and may only make itself known many years later.

Green first described this phenomenon in 19631 and other authors have detailed different ways that a lost contact lens can present, such as an eyelid mass,2 upper lid retraction,3 ptosis,4 peripheral ulcerative keratitis5 or an anterior orbital mass similar to this case.6 More recently a hard contact lens was discovered during a refractive surgery procedure, thought to have been lost 10 years previously.7

In a review of six similar cases, the authors noted four lenses had migrated into the eyelid, one into the orbit and one spontaneously reappeared on the cornea after 12 years.8 The prevalence of this phenomenon is twice as common in women as men, reflecting the increased use of contact lenses among women.9

The uninflamed nature of the lesion, with no symptoms other than the presence of a mass, which can remain without symptoms for many years, emphasises the extremely inert nature of polymethylmethacrylate, from which hard contact lenses are made. Focal giant papillary conjunctivitis is also sometimes present, but is more common with a retained soft contact lens.10

Constant movement of the eyelids may cause invagination and encysting of these inert foreign bodies with minimal granulation tissue. Another theory is that the lens engages the upper border of the tarsal plate and becomes trapped, causing pressure necrosis of the underlying tissue and eventual migration of the lens into the tissue11

This patient made a full recovery following surgical removal of the hard contact lens from the undersurface of the upper eyelid. However without a full history and careful examination, she may have been subjected to unnecessary investigations and surgery to determine the aetiology of her anterior orbital mass.

This case serves to remind clinicians of the importance of a full history with careful attention to detail on contact lenses, types used now and in the past, any history of lost lenses and trauma as well as a full examination including double eversion of the eyelids.

Learning points

Although the majority of contact lens wearers use soft contact lenses, a significant minority still use hard contact lenses.

Always take a detailed history from anyone with an orbital mass, including details of any contact lens wear.

A full ocular examination includes double eversion of the upper eyelid.

Hard contact lenses are made of an inert material and can become embedded in the upper eyelid for many years and may even migrate deeper into the orbit.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Green WR. An embedded (“lost”) contact lens. Arch Ophthalmol 1963; 69: 23–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones D, Livesey S, Wilkins P. Hard contact lens migration into the upper lid: an unexpected lid lump. Br J Ophthalmol 1987; 71: 368–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinstein GS, Myers BB. Eyelid retraction as a complication of an embedded hard contact lens. Am J Ophthalmol 1993; 102: 116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel NP, Savino PJ, Weinberg DA. Unilateral eyelid ptosis and a red eye. Surv Ophthalmol 1998. 43: 182–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatt PR, Lam FC, Roberts F, et al. Peripheral ulcerative keratitis due to a ‘long lost’ hard contact lens. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2007; 35: 550–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedberg ML, Abedi S. Encysted hard contact lens appearing as an orbital mass. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 1989; 5: 291–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cua IY, Pepose JS. Retained contact lens for more than 10 years in a laser in situ keratomileusis patient. J Cataract Refract Surg 2003; 29: 2244–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts-Harry TJ, Davey CC, Jagger JD. Periocular migration of hard contact lenses. Br J Ophthalmol 1992; 76: 95–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sebag J, Albert DM. Pseudochalazion of the upper lid due to hard contact lens embedding – case reports and literature review. Ophthalmic Surg 1982; 13: 634–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stenson S. Focal giant papillary conjunctivitis from retained contact lenses. Ann Ophthalmol 1982; 14: 881–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bock RH. The upper fornix trap. Br J Ophthalmol 1971; 55: 784–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]