Abstract

αB-crystallin (αB) is known as an intracellular Golgi membrane-associated small heat shock protein. Elevated levels of this protein have been linked with a myriad of neurodegenerative pathologies including Alzheimer disease, multiple sclerosis, and age-related macular degeneration. The membrane association of αB has been known for more than 3 decades, yet its physiological import has remained unexplained. In this investigation we show that αB is secreted from human adult retinal pigment epithelial cells via microvesicles (exosomes), independent of the endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi protein export pathway. The presence of αB in these lipoprotein structures was confirmed by its susceptibility to digestion by proteinase K only when exosomes were exposed to Triton X-100. Transmission electron microscopy was used to localize αB in immunogold-labeled intact and permeabilized microvesicles. The saucer-shaped exosomes, with a median diameter of 100–200 nm, were characterized by the presence of flotillin-1, α-enolase, and Hsp70, the same proteins that associate with detergent-resistant membrane microdomains (DRMs), which are known to be involved in their biogenesis. Notably, using polarized adult retinal pigment epithelial cells, we show that the secretion of αB is predominantly apical. Using OptiPrep gradients we demonstrate that αB resides in the DRM fraction. The secretion of αB is inhibited by the cholesterol-depleting drug, methyl β-cyclodextrin, suggesting that the physiological function of this protein and the regulation of its export through exosomes may reside in its association with DRMs/lipid rafts.

Keywords: Eye, Golgi, Heat Shock Protein, Lipid Raft, Protein Secretion, Crystallin, Exosome, Retinal Pigment Epithelium, Small Heat Shock Protein

Introduction

The small heat shock protein, αB-crystallin (αB)2 is a developmentally regulated gene product whose association with multiple pathologies of varied antecedents such as neurodegeneration, oncogenesis, and cataracts suggests a vital function for this protein (1–3). Elevated levels of αB have been reported in Alexander, Alzheimer, and Parkinson diseases. It is expressed in astrocytes (4) and has been implicated in peripheral nerve myelination (5). It is known to be one of the main antigens involved in multiple sclerosis (6). Its expression in a subset of basal-like breast carcinomas has led to its characterization as a novel oncoprotein (7). It is also a potential tissue biomarker for renal cell carcinoma (8). Interestingly, αB has also been shown to activate T cells (9) and inhibit platelet aggregation (10).

In the eye, apart from its predominant presence in the ocular lens, αB was initially reported in primary cultures of human retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) (11) and has since been shown to be expressed in the retina (1) and during early development of the rat eye in the embryonic RPE (12). It is highly expressed in rod outer segments as well as in the rat RPE, following intense light exposures that lead to photoreceptor cell degeneration (13). In age-related macular degeneration, high concentrations of αB transcripts are found in microdissected retinal tissue juxtaposed with subretinal lipoprotein deposits, known as “drusen” (14) and has been suggested to be a reliable marker of the progression of this neurodegeneration (15).

At the molecular level, αB has been shown to have antiaggregation properties in vitro (3). When introduced into cells in culture, it protects them against apoptosis (1, 16) by interfering with caspase conversions (16) and/or mitochondrial processes that are obligatory for cell death (17, 18). It has also been found in the nucleus (19) and within the nucleus, has been detected in SC35 speckles (20). It interacts with 20 S proteasomal subunit C8/α7 (21) and is reported to be involved in ubiquitin-dependent cyclin D1 proteolysis (22).

Notwithstanding the abovementioned important activities reported for αB, a common thread that would explain the basic fundamental function of this protein remains to be established. For instance, this protein, in addition to being a component of extracellular age-related lipoprotein deposits in various neurodegenerations, is also known to activate T cells in multiple sclerosis (9) and inhibit platelet aggregation (10). The physiological basis of these seemingly extracellular activities (23) of a protein known to be intracellular has not been addressed. We now show that it associates with detergent-resistant microdomains (DRMs) or lipid rafts and is secreted out of the cell via exosomes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

The following reagents and inhibitors were used: acetylthiocholine iodide, 5,5′-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) (Ellman's reagent), sodium azide (NaN3), methyl β-cyclodextrin (MBCD), proteinase K (Sigma), and protein transport inhibitors Golgi stop (monensin), Golgi plug (brefeldin A) (BD Biosciences Pharmingen), tunicamycin, and nocodazole (Sigma).

Adult human retinal pigment epithelial cells (ARPE19) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). In all experiments serum (Thermo Scientific) was filtered (0.22 μm) and centrifuged (110,000 × g) for 16 h to remove endogenous exosomes before use (24).

Antibodies

Anti-αB was made commercially by Sigma-Genosys (Woodlands, TX) (25). Anti-GM130, anti-flotillin-1, and anti-Hsp70 were purchased from BD Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY. Anti-cytochrome c, anti-caveolin-1, anti-LAMP-1 (lysome-associated membrane protein), and anti-calnexin were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA. Anti-α-enolase was from GeneTex (San Antonio, TX). Anti-Na+/K+-ATPase was from Pierce/Thermo Scientific, and anti-galectin-3 was from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Pierce), were used for the detection of αB, caveolin-1, calnexin, Hsp70, GM130, and galectin-3. For flotillin-1, HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., and for α-enolase, from Abcam.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

ARPE19 cells were synchronized using double thymidine block, and immunofluorescence confocal microscopy was done as described (25). Anti-αB is a polyclonal peptide antibody made against the C terminus of this protein, and GM130 is commercial monoclonal antibody (25). Leica confocal software, version 2.61, LCS Lite software (Leica Microsystems, Heidelberg, GmbH) was used to quantify the colocalization of αB with GM130 (see Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

αB is a Golgi membrane-associated protein in ARPE cells. A, sucrose density gradient fractionation of the postnuclear homogenate of confluent ARPE cells is shown. The top panel is an immunoblot showing the predominant presence of αB in Golgi membrane fractions (black line), as indicated by GM130 distribution (second panel). The bottom three panels show immunoblots with calnexin, cytochrome c (Cyto C), and Na+/K+-ATPase used as endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, and plasma membrane markers, respectively. Protein markers are shown on the left in the top panel. Ext, total cell extracts before fractionation. B, confocal images show perinuclear colocalization of αB (red) and the Golgi membrane-specific protein GM130 (green). This colocalization is lost upon treatment of cells with brefeldin A (BFA) (lower panel). Scale bar, 20 μm. Approximately 40% of αB colocalizes with GM130; in brefeldin A-treated cells this falls to 2%.

Processing of ARPE Culture Medium

ARPE19 cells, about 70% confluent (∼1 × 106 cells), in a 75-cm2 flask, were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). DMEM:Ham's F12 (1:1) medium, with or without serum (10% FBS), containing antibiotics was used to culture the cells for following the secretion of αB. For all experiments where the presence of αB outside the cell was followed, the culture medium was filtered (0.22 μm MillexGP, Millipore) and centrifuged sequentially (26) (at 300 × g for 6 min, 3000 × g for 20 min, and 5000 × g for 10 min) (discarding the pellet, if any, at each stage). The medium was concentrated (3K MWCO concentrators, Millipore) and used for various procedures including the isolation of exosomes (see below).

Cell Viability Assay

Cell death/damage was determined by lactate dehydrogenase activity in the medium using a commercial kit (Biovision, Mountain View, CA). Cell viability was assayed by trypan blue staining and direct cell counting using a hemocytometer (Reichert Scientific Instruments, Buffalo, NY) (supplemental Figs. S1–S3).

αB Secretion from Apical and Basal Surfaces of ARPE Cells

ARPE19 cells were grown for 3 weeks to confluence in medium (containing serum) on 24-mm diameter, 0.4-μm pore size Transwell inserts (Corning Inc., Corning, NY). Transepithelial resistance was measured (27) across the monolayers, every week, over a 3-week time period using STX-2 chopstick electrodes connected to an EVOM epithelial Voltohmmeter (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). The final resistance across the monolayer was calculated (see Fig. 4A). After 3 weeks the medium was aspirated, the cells were rinsed three times with PBS and then allowed to grow in serum-free medium for 12 h. The apical and basal media, respectively, were pooled from 6 individual wells for each side for the detection of αB.

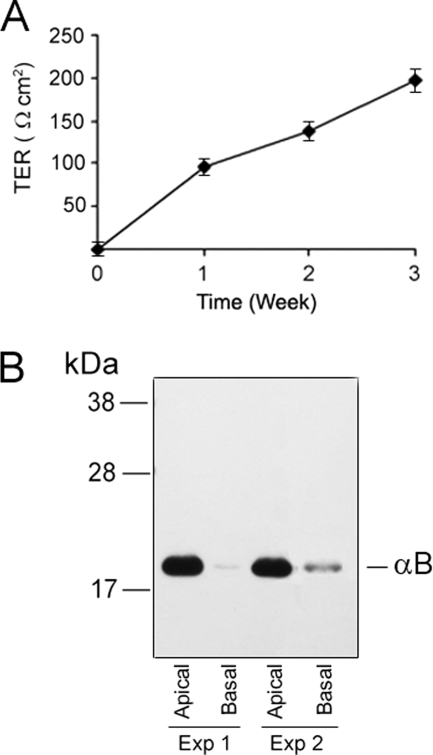

FIGURE 4.

αB is released predominantly from the apical face of human ARPE cells. Human ARPE19 cells were grown on Transwell culture inserts (see “Experimental Procedures”) for about 3 weeks with regular monitoring of the trans-epithelial resistance. A, in transepithelial resistance (TER) measurements of ARPE cells, the data are represented as mean ± S.E. (error bars, n = 3). The resistance across the ARPE monolayer is measured using EVOM chop stick electrode and calculated (TER = Ω × cm2). B, the experiment was started by changing the medium on the apical as well as basal compartments and waiting 12 h before the medium was collected from respective compartments, concentrated, and immunoblotted. Note preferential presence of αB in the apical medium. Data from two different experiments are shown.

Two-dimensional Gel Electrophoresis

The ARPE19, total protein extracts and concentrated culture medium samples (∼60 μg) were separated on immobilized pH gradient strips (IPG, 7 cm, pH 5–8), on PROTEAN IEF cell (Bio-Rad) for the first dimension and on SDS-PAGE (Invitrogen) for second dimension. The gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and processed for immunoblotting (25).

Sucrose Density Gradients

Discontinuous sucrose density gradients were used for the analyses of the postnuclear homogenates (see Fig. 1A) and culture medium (see Fig. 5) as described previously (25). Acetylcholinesterase activity was assayed as described (28).

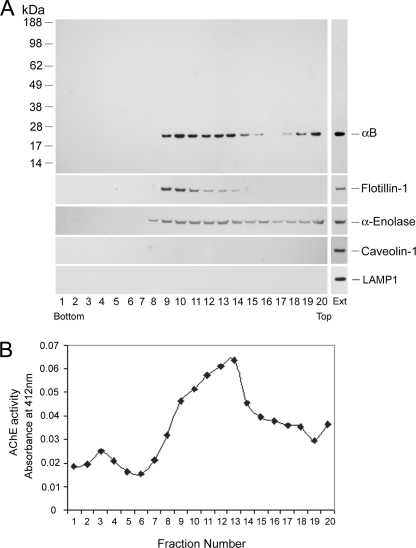

FIGURE 5.

αB is secreted in exosomes. A, sucrose density gradient fractionation profile of the concentrated medium. Various proteins including αB were detected by immunoblotting of the gradient fractions. The top panel shows that there are two distinct pools of αB in the gradient, the predominant membrane-associated fraction in the middle and the minor fraction on the top. In this panel the protein markers are on the left. The presence of flotillin-1 and α-enolase in second and third panels, respectively suggests the existence of exosomes in these fractions. Caveolin-1 and LAMP-1 were not detected in the gradient. The vertical panels (on the right) show positive controls with total cell extracts (Ext). B, acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity in various fractions of the gradient shown in A. That αB is vesicle-associated is corroborated by the presence of acetylcholinesterase activity in these fractions.

OptiPrep Density Gradient

OptiPrep (iodixanol; Sigma) gradients were used for fractionation of DRMs from total cell lysates (see Fig. 6A) as described previously (29) with minor modifications using smaller volume centrifugation (Sorvall Discovery M150 centrifuge; Kendro Laboratories, Newtown, CT). This gradient was also used to fractionate the concentrated culture medium of cells treated with MBCD (see Fig. 6B) The concentrated culture medium was mixed with 60% iodixanol (in 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100) to make it to 40% iodixanol (final concentration) before loading it into the bottom of the gradient tube. The rest of the gradient was made as for the cell lysate (29).

FIGURE 6.

αB is associated with lipid rafts/DRMs. A, total cell extracts were fractionated on OptiPrep gradients (29). Top panel (−MBCD) shows that a significant amount of αB is associated with DRMs or lipid rafts (indicated by a line, fractions 2–4). In the lower panel cells were exposed to MBCD (5 mm, +MBCD) for 6 h prior to fractionation. Note that with +MBCD, both αB and caveolin-1 are significantly lost from the DRM fractions. There are differential effects of this drug on Hsp70 and flotillin-1. B, fractionation of the medium from the MBCD-treated and control cells on OptiPrep gradients. The concentrated medium without any further manipulations was loaded into the bottom of the gradient and fractionated as in A. There is no detectable αB in the medium analyzed from +MBCD cells. However, flotillin-1 and Hsp70 (both reduced) are still seen in the gradient, which has now shifted toward the bottom of the gradient, suggesting disruption of vesicle formation. The right column shows positive controls for all the antibodies used. Ext, total cell extract; Med, medium before fractionation.

Isolation of Exosomes

The concentrated medium, processed as indicated above was centrifuged in 12-ml polyallomer tubes (SW 40-Ti rotor) in Optima LE-80K ultracentrifuge (Beckman-Coulter) at 110,000 × g at 4 °C for 16 h (26). The supernatant was rejected, and the translucent pellet was rinsed three times with PBS (12 ml) by centrifugation at 110,000 × g for 1 h each time. The rinsed pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of PBS for downstream processing.

Proteinase K Susceptibility

Assessment of Proteinase K digestion of αB in exosomes was performed as published previously (30). Exosome pellets obtained from the culture medium of ARPE cells were treated with 400 ng of proteinase K (Sigma-Aldrich) in a reaction containing 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and Triton X-100 (0.25% or 0.5%) for 1 h at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of loading buffer and heated at 95 °C for 5 min before SDS-PAGE (4–12% gels). The protein digestion was followed by immunoblotting as above.

Immunogold Labeling of Exosomes and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Exosome pellets were prepared for negative staining and immunogold double labeling employing a slightly modified procedure (26). Using wide bore tips, 3 μl of exosome pellet was gently placed on 200-mesh Formvar-coated copper grids, allowed to adsorb for 4–5 min, and processed for standard uranyl acetate staining. In the last step, the grid was washed with three changes of PBS and allowed to semidry at room temperature before observation in TEM (CM120 Philips 120 kV).

For immunogold double labeling (with anti-αB and anti-Hsp70) the exosome pellet suspension was fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS; 4 μl of this fixed sample was placed on 300-mesh gold grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA), which were previously coated with carbon. The sample was allowed to adsorb for 15 min at room temperature followed by incubation for 15 min with 4 μl of blocking buffer (0.2% BSA and 5% normal goat serum in PBS) and finally by incubation with anti-αB antibody (1:100) for 30 min. The grids were washed three times with PBS and incubated for 30 min with goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to 12-nm gold particles (1:200) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). After washing with PBS, this procedure was repeated (which included an incubation with blocking buffer as above) for labeling with anti-rabbit Hsp70 (1:100) and goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to 18-nm gold particles. The grids were finally washed with three quick changes of PBS and contrasted with 2% uranyl acetate for 4 min, followed by 2 changes of 2% uranyl acetate. After a wash with PBS the grids were dried at room temp for 4 min and then observed. The same procedure was followed for labeling with individual antibodies. However, in this case Triton X-100 (0.02%) was included with the blocking buffer for permeabilization.

RESULTS

αB Is Associated with Golgi Membranes in ARPE Cells

We have previously reported that αB-crystallin is a Golgi-associated protein in cultured human glioblastoma U373 cells and in the developing rat heart (25) as well as in the ocular lens (31). We repeated these experiments to investigate whether αB is also associated with the Golgi in human ARPE19 cells. Discontinuous sucrose density gradient fractionation of the postnuclear homogenate (25), made from ARPE cells, shows αB in the Golgi membrane fractions 9–13 (Fig. 1A). The position of the Golgi membrane fraction is confirmed by the GM130 immunoblot. Calnexin, Na+/K+-ATPase and cytochrome c show no correspondence with the distribution of αB in this gradient, indicating very little contribution by endoplasmic reticulum or mitochondria, respectively. These data are corroborated by immunolocalization and confocal microscopy, which shows the presence of αB in the perinuclear Golgi (Fig. 1B). The immunostaining in the perinuclear region is susceptible to pretreatment with brefeldin, a γ-cyclic lactone that causes disintegration of the Golgi (32). These data establish that αB is a Golgi-associated protein in ARPE19 cells.

Characterization of αB in Culture Medium

αB was detected in the extracellular medium of ARPE cells within the first 30 min of incubation of the confluent culture with either the serum-free medium or medium containing serum (Fig. 2). Under serum-free culture conditions, about 2.1 ng and under serum-containing culture conditions, about 3.4 ng of αB/106 cells is released into the medium at 30 min (Fig. 2). This corresponds to 0.5% of total αB in the cell at 30 min in serum-free medium and about 0.8% in the serum-containing medium. At 180 min the total amount of αB in serum-free medium is 2.08%, whereas in serum plus medium it is 4.8% of the total αB in the cell homogenate (supplemental Fig. S1D). That the presence of αB in the medium is not related to cell death was established by assessing cellular integrity by lactate dehydrogenase activity and trypan blue cell exclusion (supplemental Fig. S1, A–C). The change in lactate dehydrogenase activity is less than 1.75% from zero time point to 180 min (supplemental Fig. S1C). It is obvious that there is no αB at zero time. αB appears around the 30-min time point in the medium (Fig. 2). Because we know that αB is secreted out in serum containing medium also, if there was a relationship between lactate dehydrogenase activity in the serum and αB presence in the medium we would have found αB at time zero. Furthermore, the significance of very small changes in lactate dehydrogenase activity (1.75%) from zero time point to 180 min is difficult to assess. Therefore, we assayed for cell viability in all experiments reported here to evaluate the contribution of cell death if any, to the appearance of αB in the medium. The cell viability does not change during this interval (see supplemental Fig. S1B).

FIGURE 2.

Time course of the appearance of αB in culture medium. The cells were grown to 70% confluence in serum containing medium, washed three times, and incubated with fresh prewarmed serum-free medium (SF) or with fresh prewarmed serum-containing (+serum) medium (SM) for the indicated time periods. Separate flasks (three for each time point) were used. One flask per time point was used for cell counting. αB was detected by immunoblotting (insets) of the concentrated medium and quantified using recombinant αB standards on the same blots. For serum-free medium, protein, 40 μg/lane, was analyzed for each time point. For serum-containing medium, however, comparable volumes were used, which contained more than 200 μg of total protein per lane (because of the presence of serum). The percentage of total αB in the medium has been plotted and shown in supplemental Fig. S1D.

To understand the physiological basis of the secretion of αB, we used a number of known inhibitors of various processes that are associated with protein secretion. We first used sodium azide, a known inhibitor of cytochrome c oxidase and oxidative phosphorylation. At low concentrations it had little effect on the appearance of αB in the medium (supplemental Fig. S2, A–C), suggesting an energy-independent mechanism in the secretion of this protein. We also used the following inhibitors of protein secretion 1): brefeldin A, which disorganizes the Golgi and inhibits protein transport from ER to Golgi; 2) monensin, an inhibitor of trans-Golgi and retrograde transport of glycoproteins; 3) tunicamycin, an inhibitor of N-glycosylation; and 4) nocodazole, a microtubule-depolymerization agent (supplemental Fig. S2, D–G). None of the above well established inhibitors of classical protein transport impacted the αB appearance in the medium. We, therefore, investigated alternative modes of secretion of this protein.

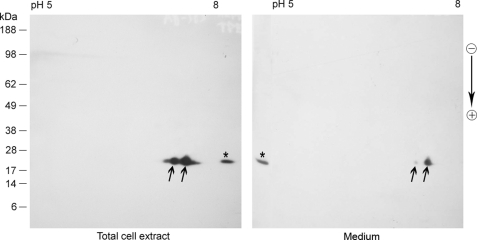

We first assessed the status of αB inside and outside of the cell by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis) and immunoblotting (Fig. 3). These data indicate that there are no noticeable differences in the protein inside the cell and in the medium. Considering that RPE is a polarized epithelium (33), we investigated the secretion of αB from the basal and apical face of ARPE19 cells, whose trans-epithelial resistance was monitored for about 3 weeks (Fig. 4A) before starting the experiment. Interestingly, the data show predominant secretion of αB from the apical face (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 3.

Secreted αB is similar to intracellular protein. αB in the total cell extract and in the medium was characterized by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting. The arrows indicate two differentially phosphorylated isoforms of the protein. *, respective aliquots run only on the second-dimension gel. Arrow on the right indicates the direction of second-dimension SDS-PAGE. Protein markers are shown on the left.

We next investigated the status of αB in the culture medium. This was done by fractionation of the concentrated culture medium on a discontinuous sucrose density gradient (25). Most of αB sediments at 0.5 m/0.86 m sucrose interphase, with the membrane fractions 9–13 (Fig. 5A, top panel). There is also a distinct pool of αB on the top of the gradient (fractions 18–20, 0.25 m sucrose). The association of αB in the medium with the membrane suggests its possible presence in vesicles. To ascertain this, we probed the distribution of exosome and lipid raft markers (26) such as flotillin-1, caveolin-1, α-enolase, and LAMP-1 in the gradient (Fig. 5A, lower panels). Flotillin-1 and α-enolase are detected in the same fractions as αB, suggesting the presence of vesicles in these fractions. Importantly, no caveolin-1 or LAMP-1 is detected, indicating that this membrane fraction represents microvesicles derived from DRMs, which are neither associated with the plasma membrane structures, such as caveolae, nor with the endolysosomal compartment (34).

We further characterized the gradient by assaying for acetylcholinesterase activity, an enzyme specific to microvesicles or exosomes (28). The enzyme activity was detected predominantly in the membrane fractions 9–13 (Fig. 5B), the same fractions where αB is found (Fig. 5A), suggesting association of this protein with microvesicles. These data led to the conclusion that αB is released as a membrane-associated protein into the ARPE culture medium, potentially packaged in microvesicles (exosomes).

αB Is Associated with Lipid Rafts/DRMs

DRMs/lipid rafts are part of exosome biogenesis (35). Whole cell homogenates were fractionated on OptiPrep gradients, and fractions were immunoblotted for αB and various lipid raft/DRM resident proteins. We found αB in DRM fractions 2–4, at the top of the gradient (Fig. 6A). This fraction also contains DRM markers, namely caveolin-1, Hsp70, and flotillin-1. Caveolin-1 is detected exclusively in fractions 2–4. Flotillin-1 and Hsp70, although distinctly associated with the raft/DRMs, are also present in the rest of the gradient. This distribution is similar to the overall distribution of αB. Both αB and caveolin-1 are lost from DRMs when cells are treated with the cholesterol-depleting drug, MBCD (5 mm) (Fig. 6A, lower panel). Interestingly, the association of flotillin-1 and Hsp70 with the lipid raft/DRM fraction is not drastically effected. This may be explained by the known heterogeneity of the effects of MBCD on DRM proteins (24, 29). The differential response to various metabolic inhibitors may also be dictated by cell type specificity of the proteins associated with DRM (35, 36).

Based on the data presented in Fig. 5A (sucrose density gradient of the culture medium) we analyzed the culture medium on OptiPrep gradients (Fig. 6B). We simply concentrated the medium and brought it up to the same buffer conditions that were used for fractionation of the cell lysates and loaded it for fractionation. There is no distinct DRM fraction here, but we see αB, flotillin-1, and Hsp70 at similar positions in the gradient. Importantly, we see that MBCD inhibits the secretion of αB (Fig. 6B, +MBCD). As also seen in Fig. 6A, MBCD has differential effects on the OptiPrep gradient patterns of Hsp70 and flotillin-1. In both cases, however, the amount of protein is reduced, and the pattern seems to shift to the right (bottom) indicating loss of lipid in these fractions in the medium of ARPE cells treated with MBCD (Fig. 6B) (see supplemental Fig. S3 for cell viability assays associated with these experiments).

Characterization of αB in Exosomes

Based on the data presented in Figs. 5 and 6, lipoprotein vesicles were isolated by high speed centrifugation (26) and analyzed for “exosome” markers (flotillin-1, α-enolase, and Hsp70) and αB (Fig. 7A). Fig. 7B is a negatively stained preparation showing doughnut/saucer shapes, characteristic of exosomes. Fig. 7C shows that the median diameter of these vesicles is 100–200 nm. These vesicles, therefore, could also be catalogued as microvesicles, as has been suggested for subcellular compartments that range in size from 50 to 1000 nm (37). Fig. 8, A and B, shows that unpermeabilized vesicles are immunolabeled by anti-αB and anti-Hsp70. Because the proteins are supposedly inside the vesicle, labeling of vesicles raises important questions about whether the protein is inside the vesicle or travels as an adherent. Fig. 8C shows that the protein in the culture medium is resistant to proteinase K digestion (lane 2) but becomes susceptible in presence of Triton X-100 (lane 3), suggesting that the protein is protected by the vesicle. To address this further, exosomes were isolated from two different preparations and subjected to proteinase K digestion (Fig. 8D). Only when treated with Triton X-100, does the protein become susceptible to proteinase K digestion (Fig. 8D, lanes 3 and 4). These data establish the presence of αB in the exosomes. Based on this experiment (Fig. 8, C and D) vesicles were treated with Triton X-100 before immunogold labeling. Robust labeling is seen in detergent-treated vesicles. Fig. 9A shows a collapsed vesicle (large open arrow), produced by the mild exposure to the detergent (0.02% Triton X-100), with markedly increased detection of αB (thin arrows), suggesting that all of this protein is not accessible when the vesicles are intact (Fig. 8, A and B). Fig. 9B shows increased labeling for Hsp70 as would be expected (see supplemental Fig. S4 for preimmune controls).

FIGURE 7.

Exosomes isolated from ARPE cells contain αB, Hsp70, flotillin-1 and α-enolase. A, complete immunoblot with anti-αB. Protein standards are on the left (top panel). The bottom three panels show only the relevant part of the respective immunoblots. E, total cell extract; P, exosome pellet obtained from the medium; S, supernatant from the exosome pellet. Lane E contains 40 μg of protein; lanes P and S contain comparable volumes of resuspended exosome pellet and concentrated supernatant (medium), respectively. B, TEM of uranyl acetate-stained exosome pellet. Note the characteristic saucer-shaped vesicles. C, size distribution of exosomes seen in B.

FIGURE 8.

TEM-immunogold labeling of the native exosomes and resistance of exosomal αB to proteinase K digestion. A and B, exosome pellets processed for immunogold labeling without permeabilization. Double labeling was done using antibodies, anti-αB and anti-Hsp70. Hsp70 was used as a marker because this protein has been shown to be present in exosomes. Goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to 12-nm (arrows) and 18-nm (arrowheads) gold particles was used for the detection of αB and Hsp70, respectively. Not all vesicles are labeled by both antibodies. Some vesicles are unlabeled, which is expected because the vesicular structures are intact. In the case of αB, the antibody is against the C terminus (25), which may be more accessible (3). C, susceptibility of αB to proteinase K in concentrated culture medium before isolation of exosomes. Digestion was followed by immunoblotting of the reactions. The protein in the medium is resistant to proteinase K digestion in the absence of Triton X-100 (lane 2). D, immunoblot of isolated exosome pellet subjected to proteinase K digestion in the absence (lanes 1 and 2) and in the presence (lanes 3 and 4) of Triton X-100 (0.25%, lane 3; 0.5%, lane 4).

FIGURE 9.

TEM-immunogold labeling of exosomes exposed to Triton X-100. A, collapsed vesicle (permeabilized with 0.02% Triton-X100) immunogold-labeled with anti-αB. There is enhanced labeling of αB (12-nm gold particles, arrows) because of increased accessibility of the protein. B, TEM of Triton X-100-treated exosome pellet labeled with anti-Hsp70 (18-nm gold, arrows). See supplemental Fig. S4 for preimmune controls.

DISCUSSION

αB is known to be an intracellular protein; its primary sequence does not have any signatures, such as a signal peptide for secretion. It is, however, found associated with the Golgi in various tissues and cells (25, 31), including the ARPE19 cells (Fig. 1). In this investigation we demonstrate that αB is secreted out of the ARPE cells packaged in exosomes. It is significant that the two isoforms of αB, known to be related to phosphorylation (38), are both seen inside the cell as well as outside in the culture medium (Fig. 3, arrows). This protein, however, does get O-GlcNAc on threonine 170 (39), which explains its passage through Golgi. Importantly though, tunicamycin does not seem to impact the secretion of αB (supplemental Fig. S2D), thereby suggesting that this modification may not be important for its export out of the cell. Thus, it is conceivable that although O-GlcNAc-modified protein may have diverse destinations, possibly including the cell surface and the nucleus, the unmodified αB, a protein without a signal peptide, must come out of the cell, bypassing the endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi pathway via exosomes.

It is interesting to examine the confocal microscope images presented in Fig. 1B. In addition to plasma membrane labeling with anti-αB, it seems that αB is localized to some larger structures in the cytoplasm that are not labeled by GM130. It is possible that these structures represent multivesicular bodies (30). In some of these structures, our preliminary data show colocalization of αB with CD63 (a marker of multivesicular bodies and exosomes). Importantly, this colocalization is susceptible to tunicamycin treatment,3 suggesting that this association may be involved with part of the αB that is redistributed within the cell. However, the relevance of these findings to the export of αB via exosomes must await further investigations.

Exosomes are known to be secreted from various cell types in vitro and have been found in various body fluids such as plasma, urine, amniotic fluid, bronchoalveolar lavage, synovial and cerebrospinal fluids (40). Exosomes have also been reported from ARPE19 cells (41, 42). It is interesting to note that the presence of αB has also been reported in human tear fluid (43). It is possible that αB in the tear fluid is in exosomes.

Although αB has been identified in the total proteome of RPE (44), the reported “secretome” of RPE does not list αB as one of its proteins (45). This may be because αB and other low abundance proteins may have escaped this analysis by virtue of being encased in membranous compartments as reported here (Figs. 5–9). The resistance of αB to proteolysis (Fig. 8, C and D) establishes the presence of this protein in the lumen of the microvesicles. Additionally, the characteristic shape of the isolated exosomes, the known markers (Figs. 5 and 7), and the predominant polarized secretion (Fig. 4) all authenticate the presence of αB in exosomes.

Lipid rafts/DRMs are part of exosome biogenesis (35). They are cholesterol- and sphingolipid-rich membrane domains distinct from the rest of the more fluid plasma membrane. These structures are populated by a number of signaling protein molecules that give them their dynamic and possibly specific physiological functions (35, 36). DRMs are assembled at the trans-Golgi domains and are then incorporated into various compartments, including the endosomes, the plasma membrane, and the exosomes (35). The data presented here, while explaining the relevance of the known association of αB with the Golgi membranes (25), also point to the mechanistic basis of its presence in the exosomes through its association with DRMs.

The function of αB in microvesicles can only be speculated on at this time. Exosomes are potential extracellular signaling machines (37). For example αB-containing exosomes could stimulate T cells, known to be involved in the generation of the pathogenesis in multiple sclerosis (9, 46). Based on the data presented in this investigation, we believe that αB-containing exosomes may represent a link in the generation of αB-specific T cells without the intervention of the release of αB from oligodendrocytes through apoptosis or injury.

It is also known that αB imparts resistance to apoptosis in RPE (1); therefore, it is possible that exosomes loaded with this protein are taken up by nonexpressing cells (37), thus bypassing the need for de novo αB expression, an example of lateral transfer of molecular information. Notably, αB has also been shown to be present in interphotoreceptor matrix (47) that lies alongside the apical surface of the RPE in vivo.

The relevance of αB secretion via apical face of ARPE to its accumulation in drusen on the basal side of RPE, in age-related macular degeneration, is not obvious. But we speculate that a pathological loss of polarity could overcome this physiological/physical separation. Alternatively, the drusen (42, 48) may result from the secretory activity of αB-expressing cells, other than the RPE such as the microglia (49).

Finally, the discovery of the association αB with DRMs (Fig. 6), the potential signal-organizing centers in the cell (36), may allow a deeper insight into functional import of the membrane association of α-crystallins, reported as early as 1979 (50, 51). This subcellular location in specialized lipid domains presents a vital avenue for future investigations that may yet reveal actual mechanistic details of the physiological role of this small heat shock protein, inside the cell and outside, in the exosomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Garen Polatoglu and Josh Lee for technical help, Ankur Bhat for running the two-dimensional gel experiments, Jane Hu and Dean Bok for help with transepithelial resistance experiments and Grace Raposo for advice with isolation and identification of exosomes. We thank Drs. Joseph Horwitz and Dean Bok for reading the manuscript and for suggestions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health grants, through the NEI (to S. P. B.). This work was also supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 1S10RR23057 (to the Electron Imaging Center for Nanomachines and Z. H. Z.). A preliminary account was presented at the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Annual Meeting, Ft. Lauderdale, FL, May 3–7, 2009 (Bhat, S. P., Gangalum, R. K., and Jing, Z. (2009) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50, E-Abstr. 4183).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains a statistical analysis, Figs. S1–S4, and additional references.

R. K. Gangalum and S. P. Bhat, unpublished data.

- αB

- αB-crystallin

- DRM

- detergent-resistant membrane microdomain

- MBCD

- methyl β-cyclodextrin

- RPE

- retinal pigment epithelium

- TEM

- transmission electron microscopy.

REFERENCES

- 1. Andley U. P. (2007) Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 26, 78–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bhat S. P. (2003) Prog. Drug Res. 60, 205–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Horwitz J. (2000) Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 11, 53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Renkawek K., Voorter C. E., Bosman G. J., van Workum F. P., de Jong W. W. (1994) Acta Neuropathol. 87, 155–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. D'Antonio M., Michalovich D., Paterson M., Droggiti A., Woodhoo A., Mirsky R., Jessen K. R. (2006) Glia 53, 501–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van Noort J. M., Bajramovic J. J., Plomp A. C., van Stipdonk M. J. (2000) J. Neuroimmunol. 105, 46–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moyano J. V., Evans J. R., Chen F., Lu M., Werner M. E., Yehiely F., Diaz L. K., Turbin D., Karaca G., Wiley E., Nielsen T. O., Perou C. M., Cryns V. L. (2006) J. Clin. Invest. 116, 261–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holcakova J., Hernychova L., Bouchal P., Brozkova K., Zaloudik J., Valik D., Nenutil R., Vojtesek B. (2008) Int. J. Biol. Markers 23, 48–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chou Y. K., Burrows G. G., LaTocha D., Wang C., Subramanian S., Bourdette D. N., Vandenbark A. A. (2004) J. Neurosci. Res. 75, 516–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kozawa O., Matsuno H., Niwa M., Hatakeyama D., Kato K., Uematsu T. (2001) Cell Stress Chaperones 6, 21–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bhat S. P., Nagineni C. N. (1989) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 158, 319–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nishikawa S., Ishiguro S., Kato K., Tamai M. (1994) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 35, 4159–4164 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sakaguchi H., Miyagi M., Darrow R. M., Crabb J. S., Hollyfield J. G., Organisciak D. T., Crabb J. W. (2003) Exp. Eye Res. 76, 131–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson P. T., Brown M. N., Pulliam B. C., Anderson D. H., Johnson L. V. (2005) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 46, 4788–4795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De S., Rabin D. M., Salero E., Lederman P. L., Temple S., Stern J. H. (2007) Arch. Ophthalmol. 125, 641–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kamradt M. C., Chen F., Cryns V. L. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 16059–16063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mao Y. W., Liu J. P., Xiang H., Li D. W. (2004) Cell Death Differ. 11, 512–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yaung J., Jin M., Barron E., Spee C., Wawrousek E. F., Kannan R., Hinton D. R. (2007) Mol. Vis. 13, 566–577 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bhat S. P., Hale I. L., Matsumoto B., Elghanayan D. (1999) Eur. J. Cell Biol. 78, 143–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van Rijk A. E., Stege G. J., Bennink E. J., May A., Bloemendal H. (2003) Eur. J. Cell Biol. 82, 361–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boelens W. C., Croes Y., de Jong W. W. (2001) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1544, 311–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barbash O., Lin D. I., Diehl J. A. (2007) Cell Div. 2, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Enomoto Y., Adachi S., Matsushima-Nishiwaki R., Niwa M., Tokuda H., Akamatsu S., Doi T., Kato H., Yoshimura S., Ogura S., Iwama T., Kozawa O. (2009) FEBS Lett. 583, 2464–2468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lancaster G. I., Febbraio M. A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 23349–23355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gangalum R. K., Schibler M. J., Bhat S. P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 43374–43377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thery C., Amigorena S., Raposo G., Clayton A. (2006) Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. 3, 3.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hu J. G., Gallemore R. P., Bok D., Lee A. Y., Frambach D. A. (1994) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 35, 3582–3588 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Johnstone R. M., Adam M., Hammond J. R., Orr L., Turbide C. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 9412–9420 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Broquet A. H., Thomas G., Masliah J., Trugnan G., Bachelet M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 21601–21606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mor-Vaknin N., Punturieri A., Sitwala K., Faulkner N., Legendre M., Khodadoust M. S., Kappes F., Ruth J. H., Koch A., Glass D., Petruzzelli L., Adams B. S., Markovitz D. M. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 9484–9496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gangalum R. K., Bhat S. P. (2009) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50, 3283–3290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fujiwara T., Oda K., Yokota S., Takatsuki A., Ikehara Y. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 18545–18552 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Simó R., Villarroel M., Corraliza L., Hernández C., Garcia-Ramírez M. (2010) J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010, 190724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Escola J. M., Kleijmeer M. J., Stoorvogel W., Griffith J. M., Yoshie O., Geuze H. J. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 20121–20127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rajendran L., Simons K. (2005) J. Cell Sci. 118, 1099–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lingwood D., Simons K. (2010) Science 327, 46–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pap E., Pállinger E., Pásztói M., Falus A. (2009) Inflamm. Res. 58, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chiesa R., McDermott M. J., Spector A. (1989) Curr. Eye Res. 8, 151–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Roquemore E. P., Chevrier M. R., Cotter R. J., Hart G. W. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 3578–3586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Simpson R. J., Jensen S. S., Lim J. W. (2008) Proteomics 8, 4083–4099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McKechnie N. M., Copland D., Braun G. (2003) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44, 2650–2656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang A. L., Lukas T. J., Yuan M., Du N., Tso M. O., Neufeld A. H. (2009) PLoS One 4, e4160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. May C. A., Welge-Lüssen U., Jünemann A., Bloemendal H., Lütjen-Drecoll E. (2000) Curr. Eye Res. 21, 588–594 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. West K. A., Yan L., Shadrach K., Sun J., Hasan A., Miyagi M., Crabb J. S., Hollyfield J. G., Marmorstein A. D., Crabb J. W. (2003) Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2, 37–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. An E., Lu X., Flippin J., Devaney J. M., Halligan B., Hoffman E. P., Hoffman E., Strunnikova N., Csaky K., Hathout Y. (2006) J. Proteome Res. 5, 2599–2610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bajramovic J. J., Plomp A. C., Goes A., Koevoets C., Newcombe J., Cuzner M. L., van Noort J. M. (2000) J. Immunol. 164, 4359–4366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hauck S. M., Schoeffmann S., Deeg C. A., Gloeckner C. J., Swiatek-de Lange M., Ueffing M. (2005) Proteomics 5, 3623–3636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mullins R. F., Russell S. R., Anderson D. H., Hageman G. S. (2000) FASEB J. 14, 835–846 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Raoul W., Feumi C., Keller N., Lavalette S., Houssier M., Behar-Cohen F., Combadière C., Sennlaub F. (2008) Ophthalmic Res. 40, 115–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cobb B. A., Petrash J. M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 6664–6672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kibbelaar M. A., Bloemendal H. (1979) Exp. Eye Res. 29, 679–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.