Abstract

Macrophage foam cell is the predominant cell type in atherosclerotic lesions. Removal of excess cholesterol from macrophages thus offers effective protection against atherosclerosis. Here we report that a protein kinase A (PKA)-anchoring inhibitor, st-Ht31, induces robust cholesterol/phospholipid efflux, and ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) greatly facilitates this process. Remarkably, we found that st-Ht31 completely reverses foam cell formation, and this process is ABCA1-dependent. The reversal is also accompanied by the restoration of well modulated inflammatory response to LPS. There is no detectable toxicity associated with st-Ht31, even when cells export up to 20% cellular cholesterol per hour. Using FRET-based PKA biosensors in live cells, we provide evidence that st-Ht31 drives cholesterol efflux by elevating PKA activity specifically in the cytoplasm. Furthermore, ABCA1 facilitates st-Ht31 uptake. This allows st-Ht31 to effectively remove cholesterol from ABCA1-expressing cells. We speculate that de-anchoring of PKA offers a novel therapeutic strategy to remove excess cholesterol from lipid-laden lesion macrophages.

Keywords: ABC Transporter, Cholesterol, Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), Macrophage, Protein Kinase A (PKA), A-Kinase Anchoring Protein, ABCA1

Introduction

Cholesterol export from peripheral cells is an essential process in maintaining cholesterol homeostasis and normal cell function. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1)3 plays a key role in this cholesterol export. Dysfunctional mutations of ABCA1 in human result in Tangier disease, a disorder characterized by elevated risk of cardiovascular disease (1–4). ABCA1 is highly expressed in lipid-laden macrophages where it facilitates the removal of excess cholesterol. This prevents the formation of foam cells, the predominant cell type in atherosclerotic lesions.

At the molecular level, ABCA1 is best characterized as an essential protein for exporting cellular cholesterol/phospholipids to extracellular acceptors, such as apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I), leading to the formation of HDL. In addition, ABCA1 exports cholesterol in the form of non-HDL microparticles (5, 6). This microparticle release relies on protein kinase A (PKA) activity. ABCA1 itself can be phosphorylated by PKA (7); however, the precise consequence of this phosphorylation is not clear. A study that mutated two of the most probable PKA phosphorylation sites on ABCA1 reported no defect on cholesterol export (8). This suggests that PKA may target molecules downstream of ABCA1.

PKA is a broad spectrum Ser/Thr kinase that regulates a wide range of cellular processes. To modulate such a diverse spectrum of events with specificity, PKA has to be activated at precise cellular locations and at specific times. This spatial-temporal regulation is conveyed in part through PKA interaction with protein kinase A-anchoring proteins (AKAPs). Although structurally diverse, all AKAPs contain a PKA-anchoring domain and a specific targeting motif that dictates their subcellular localizations. AKAPs are also scaffolding proteins that sequester not only protein kinases but also phosphatases to coordinate phosphorylation dynamics (9). For example, besides PKA, most of the AKAPs also anchor phosphodiesterases that degrade cAMP, the major PKA activator. This allows AKAP to locally regulate the amplitude and duration of PKA activation. Presently, it is not known whether this spatially governed PKA activity relates to ABCA1 function or cholesterol export.

In this study, we report that st-Ht31, a membrane-permeable peptide inhibitor of PKA anchoring, increases cytosolic PKA activity and robustly exports cholesterol as microparticles. Remarkably, st-Ht31 is able to effectively reverse foam cell formation and restores metabolic health in these otherwise dysfunctional macrophages. ABCA1 greatly facilitates this process.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials and Reagents

Baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells stably transfected with a mifepristone-inducible vector containing an insert encoding ABCA1 or without insert (MOCK) were from Drs. Vaughan and Oram (University of Washington). RAW 264.7 macrophages were purchased from ATCC. Bone marrow-derived macrophages were kindly provided by Dr. Marcel (Ottawa University Heart Institute). Cell culture media and reagents were from Invitrogen, and mifepristone was from Sigma. Polyclonal antibody against ABCA1 was purchased from Novus Biological Inc. (Littleton, CO), and fluorescent secondary antibodies were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). st-Ht31 and st-Ht31-p were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Ht31 was synthesized by Dr. Basak (Ottawa Hospital Research Institute). AKAR-3 and PM-AKAR-3 probes were generous gifts from Dr. Jin Zhang (John Hopkins University).

Cell Culture

BHK cells and RAW 264.7 macrophage were cultured in DMEM plus 10% fetal calf serum and penicillin/streptomycin. To induce expression of ABCA1, BHK cells were incubated with 5 nm mifepristone in DMEM containing 1 mg/ml BSA, and RAW macrophages were induced with 0.3 mm Br-cAMP for 18–20 h. Bone marrow cells were obtained by flushing the femurs of ABCA1+/+ and ABCA1−/− C57 mice, respectively. Macrophages were generated by incubating bone marrow cells (106 cells/ml) with DMEM of 10% FBS complemented with 15% L929 conditioned medium for 7 days.

Cholesterol Efflux

BHK or RAW macrophage cells were incubated in growth medium containing 1 μCi/ml [3H]cholesterol for 1–2 days. The medium was replaced by fresh DMEM containing 1 mg/ml BSA plus mifepristone or Br-cAMP. The cells were then incubated with 5 μg/ml apoA-I or st-Ht31 for 2 h at 37 °C. The amount of [3H]cholesterol in the medium and in cells was counted by scintillation. Efflux was expressed as the percentage of cholesterol in the medium over total cholesterol (medium and cell). The results are presented as the averages of triplicate wells with standard deviation.

FRET-based PKA Activity Assay

BHK cells were grown in 35-mm glass coverslip bottom microscope dishes and transfected with AKAR3 or pm-AKAR3 constructs using Lipofectamine 2000. 20–24 h after transfection, CFP, YFP, and CFPex/YFPem fluorescent images were taken with a 60×/1.4NA objective on an inverted Nikon fluorescent microscope (TE2000-E) equipped with a CCD camera and MetaMorph software (for details on filters, see Ref. 10). At least 10 fields were taken for each condition. After background and cross-talk correction, the sensitized YFP (CFPex/YFPem) image was ratioed to the correspondent CFP image from the same field to produce FRET. To analyze FRET changes, fluorescent images were taken before and after intervention, i.e. addition of st-Ht31. Changes in FRET efficiency in individual cells caused by intervention were then calculated and presented as averages of 50–100 cells and standard errors of the mean. Each experiment was repeated at least twice.

Microparticle Preparation and Characterization

The medium from BHK (ABCA1 and Mock) and RAW macrophages (induced and noninduced) was collected and centrifuged (4000 × g for 15 min and 10,000 × g for 30 min) to remove cell debris. The supernatant was then passed through a 0.2-μm filter. We have previous shown that microparticles are smaller than 0.2 μm but could not pass through a 100-kDa molecular weight cutoff filter (6). The filtrate was then washed and concentrated with a 100-kDa filter before Western blotting.

st-Ht31 Cellular Uptake Assay

st-Ht31 was fluorescently labeled with Cy2 fluorophore according to the manufacturer's instructions and added to cells for 2 h. After removing Cy2-st-Ht31-containing medium, the cells were imaged using the fluorescent microscope equipped with a CCD camera. Images from ABCA1 and Mock BHK cells were taken and presented under identical conditions.

Oil Red O Staining and Quantification

ABCA1+/+ and ABCA1−/− BMDM cells were incubated in the growth medium containing acetylated LDL (100 μg/ml) for 2 days to allow them to develop into foam cells. The medium was replaced with fresh DMEM containing 1 mg/ml BSA with or without 10 μm st-Ht31 and incubated for 24 h. The cells were then fixed with 10% formaldehyde for 1 h and stained with Oil Red O dye at 4 °C for 2 days. After removing dye, the cells were washed 6–10 times with PBS and imaged using a fluorescent microscope equipped with a cooled CCD camera. Phase contrast pictures of Oil Red O-stained cells were taken from 10 random fields under identical setting, and representative images were shown. Fluorescent images of Oil Red O were obtained with 550-nm excitation and 580-nm emission also from 10 random fields. The fluorescent intensities from each field were then quantified and divided by the number of cells in the field (400–500/field).

RESULTS

st-Ht31 Induces Robust Microparticle Release in the Absence of Extracellular Acceptor

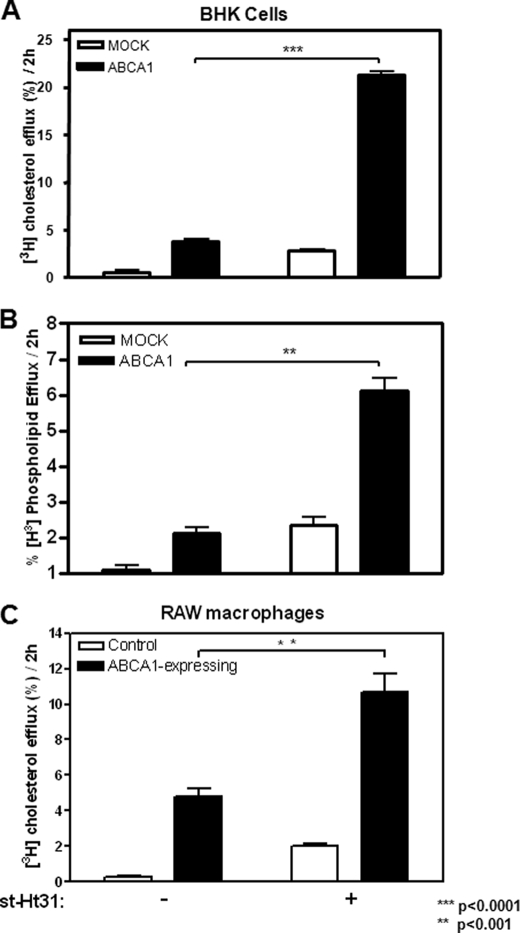

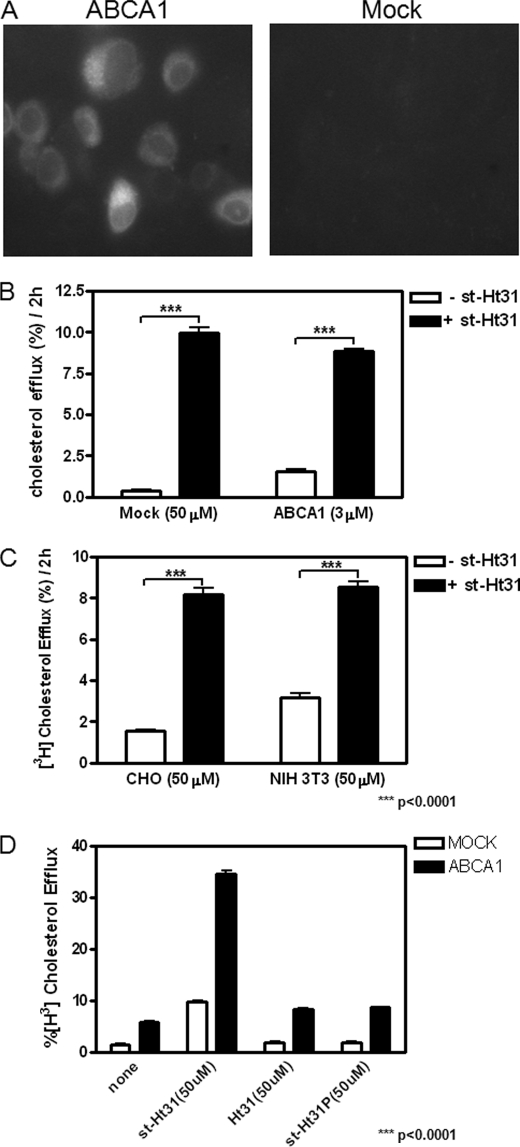

We reported previously (6) that ABCA1-expressing cells constitutively release cholesterol-rich microparticles, and this release is completely abolished by PKA inhibitor PKI, a six-residue peptide that binds PKA catalytic domain with high affinity (11). To further elaborate on this observation, we tested whether removing PKA from its anchoring sites also influences microparticle release. Ht31 is a 24-residue peptide composed of a PKA-anchoring domain of AKAP and thus binds to PKA regulatory subunit RII with high affinity (12). This prevents PKA from interacting with AKAPs. Ht31 has been frequently used to complement PKI by removing PKA from AKAP, thereby abolishing localized PKA activity (13). When we treated cells with 5 μm st-Ht31, a stearated and thus membrane-permeable form, we were surprised to see that both BHK cells and RAW macrophages robustly released microparticles, indicated by the presence of cholesterol in the medium, or cholesterol efflux, in the absence of extracellular acceptors (Fig. 1, A and C). This cholesterol release by st-Ht31 predominantly occurs in ABCA1-expressing cells. Furthermore, phospholipid efflux is similarly stimulated (Fig. 1B). Both ABCA1-expressing BHK cells and RAW macrophages responded to st-Ht31 in a dose-dependent manner (supplemental Fig. S1, A and B). At 50 μm st-Ht31 (a concentration frequently used in the literature), ABCA1-expressing BHK cells was able to export close to 40% cellular cholesterol in 2 h (supplemental Fig. S1C).

FIGURE 1.

st-Ht31 enhances cholesterol/phospholipid efflux. A, BHK cells were incubated in growth medium containing 1 μCi/ml [3H]cholesterol for 1–2 days and then induced with mifepristone overnight. Cholesterol efflux was analyzed by quantifying the percentage of cell-associated cholesterol appeared in the medium during a 2-h period with or without st-Ht31. B, BHK cells prelabeled with [3H]choline chloride were treated as in A. Phospholipids containing [3H]choline were extracted from both medium and cells to calculate the percentage of [3H]choline containing phospholipids in the medium. C, RAW macrophages were treated identically as BHK cells in A, except that they were induced with 8-Br-cAMP. The bars represent the means ± standard deviations of triplicate wells.

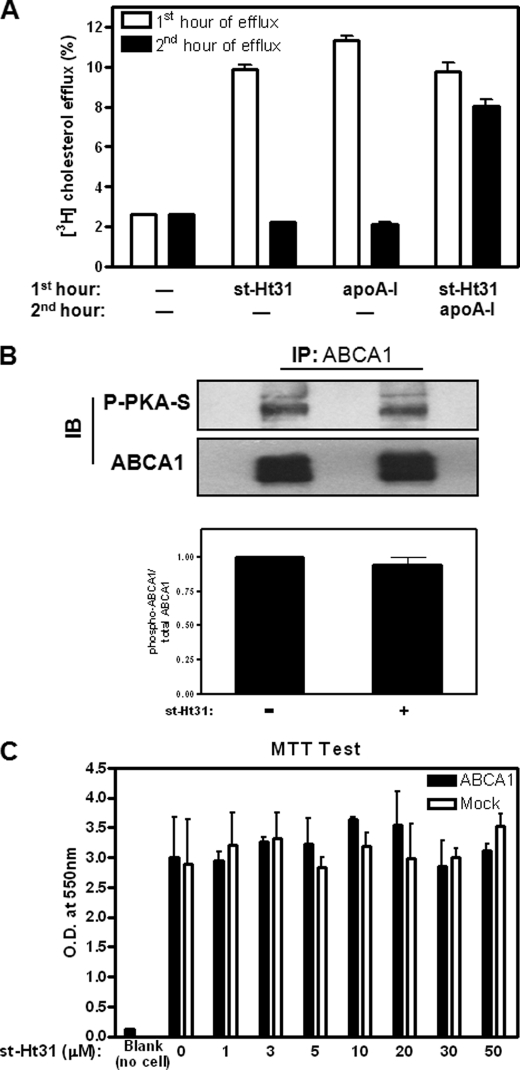

The effect of st-Ht31 is acute, because cholesterol efflux stops immediately after removal of st-Ht31 from the medium (Fig. 2A, second group of bars from the left), similar to the efflux induced by apoA-I (third group). Neither ABCA1 expression nor distribution was altered by st-Ht31 (not shown). Consistent with this, when the cells were treated with st-Ht31 for the first hour, washed, and then incubated with apoA-I for the second hour, the cells were able to efficiently export cholesterol to apoA-I (Fig. 2A, fourth group). The slightly lower cholesterol efflux to apoA-I in the second hour here, compared with cholesterol efflux to apoA-I in untreated cells (third group from left), likely reflects the cholesterol depletion by st-Ht31 during the first hour. Furthermore, we found that st-Ht31 mainly stimulates the release of microparticles, similar to the ones we reported earlier by FPLC analysis (6). ABCA1 phosphorylation by PKA was not significantly altered, as probed by an antibody recognizing phosphorylated PKA substrates (Fig. 2B). Perhaps most importantly, st-Ht31-treated cells remained perfectly viable in a wide range of st-Ht31 concentrations up to 50 μm, shown by a methylthiazol tetrazolium test (Fig. 2C), a well established metabolic assay for cell viability (14). This demonstrates that the robust cholesterol export by st-Ht31 is not due to cell damage or membrane fragmentation.

FIGURE 2.

st-Ht31 exerts no detectable toxicity and no significant influence on ABCA1 phosphorylation. A, ABCA1-BHK cells prelabeled with 1 μCi/ml [3H]cholesterol were incubated with either apoA-I (5 μg/ml) or st-Ht31 (5 μm) for the first hour. The cells were then washed and switched to DMEM or medium containing apoA-I (5 μg/ml), as indicated, for the second hour. The percentages of cholesterol appeared in the medium during the first hour (open bar) or second hour (filled bar) were analyzed. B, induced ABCA1-BHK cells were treated with st-Ht31 (5 μm) for 2 h. ABCA1 was immunoprecipitated and blotted using phospho-PKA substrate antibody and ABCA1 antibody, respectively. Representative blots from three independent experiments were shown. The bars represent the means ± standard deviations. C, induced BHK cells were treated with st-Ht31 at indicated concentration for 2 h. Methylthiazol tetrazolium toxicity tests were carried out. The results are presented as O.D. (550 nm) readings from formazan, and the bars represent the means ± standard deviation of triplicate wells. IP, immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblot.

st-Ht31 Increases PKA Activity Specifically in the Cytoplasm

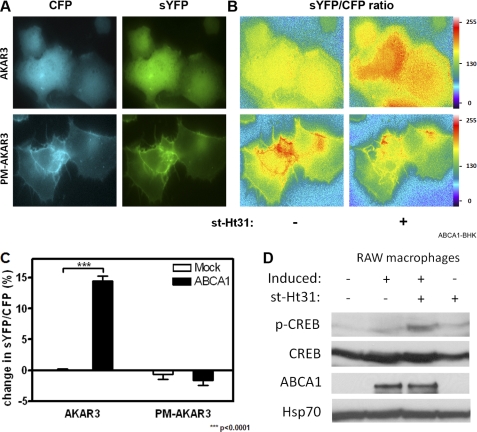

To explore the mechanism by which st-Ht31 exports cholesterol, we next analyzed spatially resolved PKA activities in st-Ht31-treated cells. Unlike PKI, st-Ht31 interferes with PKA anchoring without directly affecting PKA catalytic capacity. We reasoned that preventing PKA from anchoring should increase PKA in the cytoplasm, which in turn could elevate PKA activity specifically in the cytoplasm. Hence, we employed FRET-based biosensors to analyze compartmentalized PKA activities in live cells. The main component of the sensor, termed PKA kinase activity reporter 3 (AKAR3), is composed of a PKA substrate peptide and a phosphorylation binding domain sandwiched between cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) and yellow fluorescent protein (YFP). Upon phosphorylation by PKA, the peptide undergoes a conformational change that brings CFP in close proximity to YFP. This generates sensitized YFP or FRET signal (10) (supplemental Fig. S2A). AKAR3 can also be targeted to specific subcellular sites through additional localization motifs, which enable them to report PKA activities in their immediate environment in live cells. We were particularly interested in PKA activity in the cytoplasm as well as at the plasma membrane, because many known AKAPs are located at the plasma membrane.

AKAR3 and pm-AKAR3, a cytosolic form and a plasma membrane targeted variance, respectively (10), were expressed in ABCA1- and Mock-BHK cells. As expected, pm-AKAR3 mainly decorates the plasma membrane, whereas AKAR3 is diffusely distributed in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3A). To measure FRET, a pair of CFP and sensitized YFP images was taken from the same field of the cells before and after st-Ht31 addition (the pair taken before adding st-Ht31 is shown). Each pair of images was then processed to produce a ratio image, indicative of FRET intensity (Fig. 3B). FRET intensities before and after st-Ht31 addition were then compared and presented as percentages of change in individual cells in response to st-Ht31. The results from individual cells were then pooled to give FRET efficiency for the cell population. As shown in Fig. 3C, st-Ht31 significantly increased PKA activity in the cytoplasm of ABCA1-expressing BHK cells, as indicated by the boost in FRET change of AKAR3. The plasma membrane PKA activity, probed by pm-AKAR, did not increase by st-Ht31. Instead, there was a drop in plasma membrane PKA activity upon st-Ht31 addition, perhaps reflecting PKA de-anchoring from the plasma membrane. The response from similarly treated Mock-BHK cells was minimal (Fig. 3C). To validate our experimental protocol, we stimulated Mock-BHK cells with forskolin/isobutylmethylxanthine, which artificially activate PKA, and detected elevated FRET signals from both biosensors (supplemental Fig. S2, B and C). In addition, we probed phosphorylation of CREB, a PKA substrate. We found that st-Ht31 increases CREB phosphorylation in induced and hence ABCA1-expressing RAW macrophages, whereas this phosphorylation is minimally altered in noninduced macrophages (Fig. 3D). Together, we conclude that st-Ht31 activates PKA, and this activation is predominantly in the cytoplasm.

FIGURE 3.

st-Ht31 specifically increases PKA activity in the cytoplasm. A, ABCA1-BHK cells were transfected with either AKAR3 or pm-AKAR3 and induced overnight with mifepristone. Representative images from CFP and sensitized YFP channels were shown. B, CFP and sensitized YFP images were taken before and after st-Ht31 addition (10 min). After background and cross-talk correction, a pair of ratio images (YFP/CFP) was produced and displayed under identical setting. C, FRET intensities (YFP/CFP) were calculated for each individual cell and presented as percentages of change before and after st-Ht31 addition. The data represent the averages from 50–100 cells and standard errors of the mean. D, PKA activity was also analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against CREB and phospho-CREB. ABCA1 was probed by a monoclonal antibody. Hsp70 was used as loading control.

PKA Activity Is Required for st-Ht31-induced Cholesterol Efflux

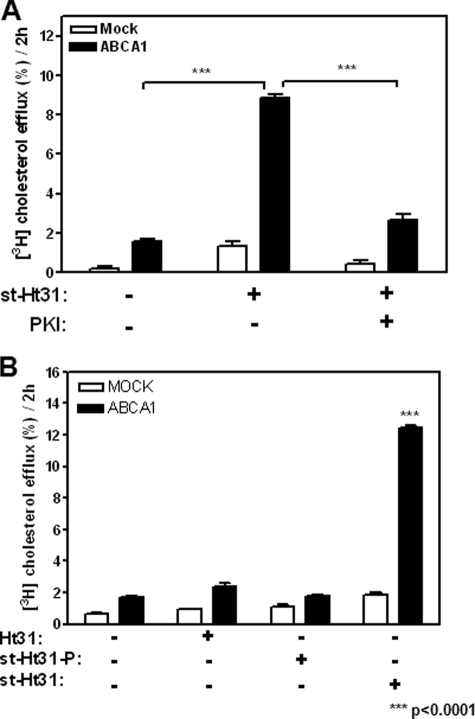

We next examined whether this elevated PKA activity is the cause of cholesterol efflux triggered by st-Ht31. If so, the cholesterol efflux stimulated by st-Ht31 should be sensitive to PKA inhibition. Indeed, we found that PKI effectively abolished this process (Fig. 4A), consistent with cytosolic PKA activation by st-Ht31.

FIGURE 4.

st-Ht31 relies on its capacity to activate PKA, de-anchor PKA, and permeate into cells to enhance cholesterol export. A, BHK cells prelabeled with 1 μCi/ml [3H]cholesterol were analyzed for their capacity to efflux cholesterol in the presence of st-Ht31 (5 μm) with or without PKI (50 μm) for 2 h. B, cells were also analyzed for their capacity to efflux cholesterol in the presence of Ht31, st-Ht31-P, or st-Ht31 for 2 h. The bars represent the means ± standard deviations of triplicate wells.

Furthermore, Ht31 is known to form an amphipathic helix (12), a functional characteristic also shared by apoA-I. We have established previously that apoA-I primarily acquires cholesterol from the plasma membrane without the need of endocytosis (15). To test the possibility that st-Ht31 might mimic apoA-I and mediate cholesterol export by lipidating itself at the plasma membrane without entering cells, we incubated cells with Ht31, a nonstearated and thus nonpermeate form. As shown in Fig. 4B, Ht31 at the similar concentration did not induce cholesterol efflux. This demonstrates that although Ht31 forms amphipathic helix, such a structure motif alone is not sufficient to acquire membrane cholesterol. Ht31 therefore cannot mimic apoA-I.

We also tested a control peptide st-Ht31-p, which differs from st-Ht31 by isoleucine-to-proline substitutions and consequently can no longer bind to PKA (12). st-Ht31-p had no effect on cholesterol efflux (Fig. 4B). Together, these experiments demonstrate that st-Ht31 exerts its influence on cholesterol efflux intracellularly and through its capacity of releasing and activating PKA.

ABCA1 Facilitates st-Ht31 Uptake to Efficiently Stimulate Cholesterol Efflux

We noted that st-Ht31 promotes cholesterol efflux primarily from ABCA1-expressing cells (Fig. 1). PKA activation by st-Ht31, as measured with FRET, is also only seen in ABCA1-expressing BHK cells (Fig. 3). To explore the mechanism by which ABCA1 accentuates the activity of st-Ht31, we tested whether ABCA1, a member of ABC transporter family, may facilitate st-Ht31 uptake. Because st-Ht31 has to reach its target, PKA, inside of cells to be effective, an efficient uptake would be necessary for its function. We therefore analyzed the uptake of a fluorescently tagged st-Ht31. Cy2-st-Ht31 functioned equally well in promoting cholesterol export as untagged st-Ht31 (not shown). When BHK cells were incubated with Cy2-st-Ht31 on ice for 2 h, we observed much more st-Ht31 taken up by ABCA1-expressing cells than by Mock cells (Fig. 5A). This suggests that st-Ht31 is able to function much more effectively in ABCA1-expressing cells, at least partially because of enhanced st-Ht31 uptake through ABCA1.

FIGURE 5.

ABCA1 expression increases permeability of st-Ht31. A, BHK cells were incubated with mifepristone overnight and then treated with Cy2-st-Ht31 (10 μm) for 2 h on ice. Images from ABCA1-BHK or Mock-BHK cells were taken under identical conditions and displayed identically. B, BHK cells were induced with mifepristone overnight. Cholesterol efflux was analyzed by quantifying the percentage of cell-associated cholesterol that appeared in the medium during a 2-h period with 50 μm (Mock) or 3 μm (ABCA1) st-Ht31. C, CHO and NIH 3T3 cells were incubated in growth medium containing 1 μCi/ml [3H]cholesterol for 1–2 days. Cholesterol efflux was analyzed by quantifying the percentage of cell-associated cholesterol appeared in the medium during a 2-h period with 50 μm st-Ht31. D, BHK cells were similarly treated as in C. The cells were then incubated with 50 μm Ht-31, st-Ht31-P, or st-Ht31, respectively, for 2 h, before cholesterol efflux analysis. The bars represent the means ± standard deviations of triplicate wells.

If st-Ht31 uptake is the key event downstream of ABCA1, we should be able to induce ABCA1-null cells to export cholesterol by forcing more st-Ht31 into these cells. We therefore treated ABCA1-null cells with 50 μm st-Ht31, a concentration more than 10 times higher than we normally used. We indeed observed a moderate cholesterol efflux from Mock-BHK cells, comparable with that from ABCA1-BHK cells treated with 3 μm st-Ht31 (Fig. 5B). Cholesterol release can also be moderately stimulated by 50 μm st-Ht31 in CHO cells and NIH 3T3 fibroblasts that express little ABCA1 (Fig. 5C). 50 μm st-Ht31, when applied to ABCA1-expressing BHK cells, was able to export large quantity of cholesterol (∼40% in 2 h; supplemental Fig. S1C) without any apparent toxicity (Fig. 2). Importantly, even at 50 μm, neither nonstearated Ht31 nor st-Ht31p, the defective mutant, was able to promote cholesterol export from ABCA1- or Mock-BHK cells (Fig. 5D). This once again supports the notion that intracellular PKA de-anchoring is essential for st-Ht31 to promote cholesterol export. Taken together, we conclude that st-Ht31 stimulates cholesterol export preferentially from ABCA1-expressing cells. This is likely due to efficient st-Ht31 uptake by ABCA1, which in turn activates PKA in the cytoplasm to promote cholesterol export.

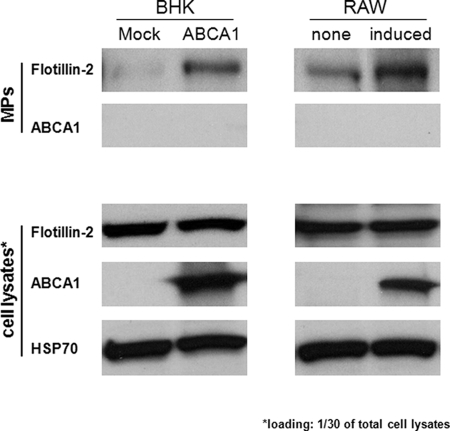

ABCA1 Likely Exports Cholesterol through Exosome Pathway

We have so far established that ABCA1-expressing cells constitutively export cholesterol because microparticles and st-Ht31 further promote this process. However, the origin of the microparticles remains elusive. It was recently reported that oligo-dentroglial precursor cells export cholesterol by exosome pathway (16). We therefore asked whether microparticle release is also through a similar mechanism. We indeed found flotillin-2, an exosome marker (17), in microparticle preparations from the medium of ABCA1-expressing BHK cells and RAW macrophages, respectively (Fig. 6). The expression of flotillin-2 is not altered by ABCA1. In addition, ABCA1 itself, a plasma membrane protein, did not appear in the microparticle preparations. Together, our observations suggest that ABCA1-expressing cells release microparticles through a mechanism similar to the exosome pathway.

FIGURE 6.

Flotillin 2 is preferentially associated microparticles released from ABCA1-expressing cells. BHK were induced with mifepriston, and RAW macrophages were either induced with 8-Br-cAMP (induced) or without (none) overnight. The medium was collected from equal numbers of cells, and microparticles (MPs) were prepared by a series centrifugation and filtration before being concentrated with a 100-kDa filter. Cell lysates ( of total) and microparticle preparations were then analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against flotillin 2, ABCA1, and HSP70, respectively.

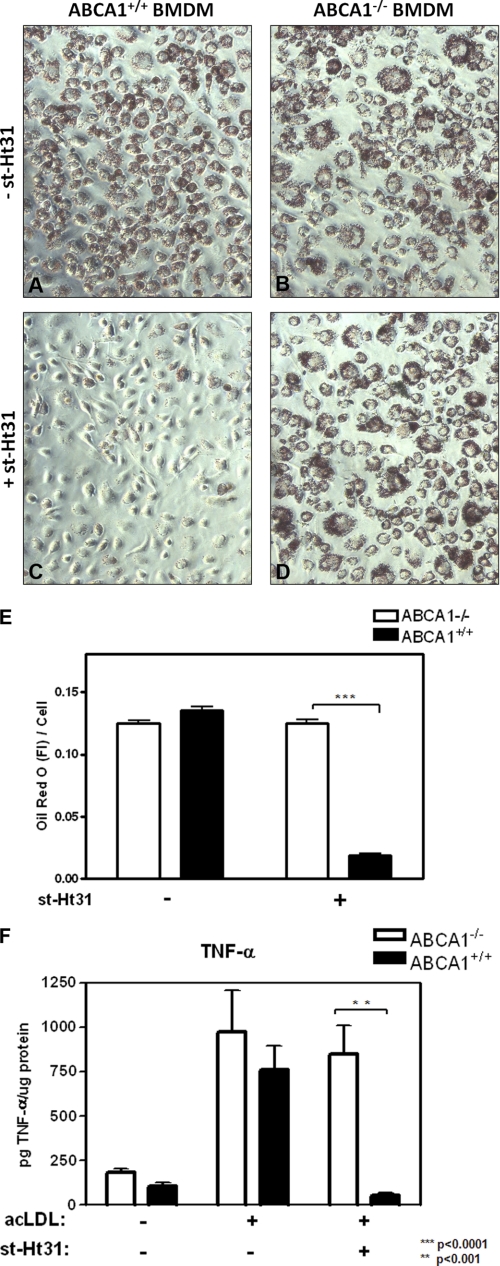

st-Ht31 Reverses Foam Cell Formation and Restores Metabolic Health of Macrophage

Perhaps most intriguingly, this ABCA1-facilitated cholesterol export by st-Ht31 may provide a unique opportunity to specifically relieve cholesterol burden from foam cells. ABCA1 is highly expressed in these macrophages as a consequence of excess cholesterol (18). st-Ht31 may preferentially remove cholesterol from foam cells, without affecting macrophages that do not express ABCA1. To test this, we fed BMDMs from ABCA1+/+ and ABCA1−/− mice with acetylated LDL for 2 days. This produces foam cells. We then removed acetylated LDL and added 10 μm st-Ht31 or medium alone for another 24 h. The cells were then stained with Oil Red O to visualize neutral lipids. Without st-Ht31, both ABCA1+/+ and ABCA1−/− BMDM remained as typical foam cells with abundant lipid droplets and heavily stained by Oil Red O (Fig. 7, A and B). With st-Ht31, however, ABCA1+/+ BMDM were almost void of neutral lipids, evidenced by greatly diminished lipid droplets and Oil Red O staining (Fig. 7C). BMDM are now restored to a much healthier morphology. In contrast, st-Ht31 had little effect on ABCA1−/− BMDM (Fig. 7D). This is consistent with our observations that, without ABCA1 to take up st-Ht31 in Mock-BHK cells or uninduced RAW macrophages, low concentrations of st-Ht31 (≪ 50 μm) were unable to induce significant cholesterol efflux (Fig. 1). We quantified Oil Red O by its fluorescent intensity (19) (supplemental Fig. S3) and found that st-Ht31 removed ∼90% neutral lipids from ABCA1+/+ BMDM foam cells but not at all from ABCA1−/− foam cells (Fig. 7E). Interestingly, the effect of st-Ht31 is reminiscent of that of apoA-I. apoA-I at 10 μg/ml was also able to fully reverse foam cell formation (supplemental Fig. S3A).

FIGURE 7.

st-Ht31 reverses foam cell formation in ABCA1+/+ BMDM, but not ABCA1−/− BMDM. A–D, BMDM from ABCA1+/+ and ABCA1−/− mice were incubated with acetyl-LDL (acLDL, 100 μg/ml) for 2 days, washed, and changed into the fresh medium with (C and D) or without (A and B) st-Ht31 (10 μg/ml) for another day (day 3). The cells were then fixed and stained with Oil Red O. E, Oil Red O fluorescence was recorded and quantified from 10 random fields and expressed as fluorescent intensity/cell. The bars are the means ± S.E. of the mean. F, similarly treated BMDM as in A–D were challenged after day 3 with LPS (100 ng/ml). The medium was collected and analyzed by ELISA for secreted TNF-α. The data are presented as the means of triplicates ± standard deviation.

Macrophages with heavy cholesterol load are known to be susceptible to excessive pro-inflammatory activation (20). We therefore tested whether st-Ht31 could rescue foam cells from such heightened inflammatory response. As shown in Fig. 7F, cholesterol loading by acetylated LDL greatly augmented LPS-induced TNF-α secretion in both ABCA1+/+ and ABCA1−/− BMDM. However, st-Ht31 was able to completely suppress TNF-α secretion in ABCA1+/+ BMDM without affecting ABCA1−/− BMDM. Once again, the suppression of TNF-α secretion by st-Ht31 is comparable with that by apoA-I (supplemental Fig. S3B), consistent with their similar capacity of removing cholesterol. Together, we conclude that st-Ht31 is capable of reversing foam cell formation in an ABCA1-dependent fashion. Perhaps more importantly, st-Ht31 is able to restore metabolic homeostasis in these macrophages such that they can now mount a well modulated inflammatory response to LPS challenge.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identify a novel mechanism that promotes robust cholesterol export in an ABCA1-dependent fashion. We provide evidence that, by inhibiting PKA anchoring on AKAPs, st-Ht31 enhances cytosolic PKA activity, and this PKA activity is essential for cholesterol export. ABCA1 facilitates st-Ht31 uptake and thereby increases the effective activity of PKA in the cytoplasm. This ultimately leads to efficient cholesterol export. Significantly, at 10 μm, st-Ht31 is able to exclusively remove lipids from ABCA1+/+ foam cells and restore these cells back to healthy macrophages. st-Ht31 at 10 μm has little effect on ABCA1−/− BMDM foam cells and on BHK cells or RAW macrophages that do not express ABCA1.

In many ways, the effect of st-Ht31 is similar to that of apoA-I. It is well established that apoA-I can relieve lipid burden from macrophage foam cells through ABCA1. We indeed observed a similar reversing effect on ABCA1+/+ foam cells by apoA-I. Through this process, apoA-I initiates the so-called “reverse cholesterol transport” that shuttles excess cholesterol to the liver for excretion. Perhaps more importantly, by removing excess lipids, apoA-I restores the healthy homeostasis in macrophages. This ensures that the macrophages can continue with their anti-inflammatory and anti-atherogenic functions. These include eliminating oxidized LDL and apoptotic bodies, modulating inflammatory processes, and repairing tissue damage. As we show here, st-Ht31 is equally as effective in reversing foam cell formation as apoA-I. In this way, st-Ht31 could play an important role in promoting healthy macrophages. Indeed, st-Ht31-treated macrophages display well modulated inflammatory responses, similar to the ones treated with apoA-I.

It is noteworthy that st-Ht31 is less than of apoA-I in size (24 amino acids versus 244 amino acids). This will likely provide a significant advantage if st-Ht31 were to be used in therapeutic interventions. st-Ht31 is similar in some ways to apoA-I mimic peptides, particularly 5A, one of the 37-pA derivatives (21). However, there is a fundamental difference between st-Ht31 and apoA-I mimics. apoA-I mimics, as the name implies, have apoA-I-like structure motifs that are capable of loading lipids onto themselves. Ht31 does not sequester lipids onto itself. Instead, it targets to a particular domain of a known molecule, PKA RII subunit, to release cellular cholesterol. This is a novel and unique advantage. The crystal structure of the PKA anchoring domain is known (22), and small nonpeptide molecules can be readily developed to target this domain. These small molecules can be further tailored to target ABCA1-expressing cells, which would allow cholesterol removal specifically from foam cells.

Suppression of inflammatory cytokine secretion by st-Ht31 is not entirely unexpected, because depleting cellular cholesterol by MCD is known to have similar effects (25). However, MCD removes cholesterol indiscriminately and suppresses inflammatory responses independent of ABCA1 expression (25). This could potentially suppress constructive inflammatory responses aimed to restore tissue homeostasis. st-Ht31, conversely, specifically modulates the pool of macrophages that are highly cholesterol-loaded and at risk of causing damage to blood vessels. Therefore, this has to be beneficial in atherogenic environments.

Currently, we do not understand the fate of the cholesterol released by st-Ht31. However, compared with the whole plasma cholesterol pool, the amount of cholesterol released from lipid-laden foam cells must be very small and will not likely influence plasma lipid profile. This is supported by the observation that macrophage-specific deletion of ABCA1 in Ldlr−/− or apoE−/− mouse models does not alter plasma lipid profile including HDL levels. Macrophage-specific deletion nevertheless significantly exaggerates atherosclerotic lesion formation (26–28). This again strongly supports the critical importance of healthy macrophages at potential lesion sites. If these macrophages remain healthy, there is a much better chance for injured vessels to be repaired even under highly unfavorable lipid environments such as those in Ldlr−/− or apoE−/− animals. It is therefore tempting to speculate that st-Ht31 or its nonpeptide analogues could exert significant anti-atherogenic functions in vivo by specifically relieving cholesterol burden from lesion foam macrophages.

This is also the first report to identify a spatial pool of PKA for cholesterol export. Interestingly, when we increased PKA activities by artificially raising cAMP levels using forskolin/isobutylmethylxanthine presumably at all cellular locations (supplemental Fig. S2), cholesterol efflux was not altered. This may reflect a necessity for finely orchestrated spatial and temporal PKA activation in biological events. The mechanism by which cytosolic PKA activation promotes cholesterol efflux remains to be determined and is currently under investigation. Another interesting aspect from the current study is that disrupting PKA anchoring on AKAP by st-Ht31 has been frequently used to inhibit local PKA activity in cells. Our study here demonstrates a previously unforeseen event: by removing PKA from anchoring sites (thus diminishing local PKA activity), st-Ht31 redistributes PKA and PKA activity. This, as shown here, has significant consequences in at least cholesterol homeostasis. At 50 μm, a frequently used concentration (29), st-Ht31 activates cytosolic PKA and depletes 10% cellular cholesterol in 2 h in cells without ABCA1. Moreover, if cells happened to express ABCA1, they could lose up to 40% cellular cholesterol in 2 h. This, undoubtedly, will significantly influence many physiological events, particularly the ones sensitive to the lipid rafts.

ABCA1/st-Ht31 releases cholesterol mainly in the form of microparticles. We presently do not understand the detailed cholesterol trafficking pathway that generates microparticles. These microparticles are uniform in size (<200 nm) and between 1.063 and 1.21 in density (6). We provide evidence here that these microparticles contain flotillin-2, an exosome marker and also a potential molecular module for exosome release (16). This suggests that these microparticles may be related to exosomes. ABCA1 and st-Ht31 may influence multivesicular body biogenesis and eventually exosome release, which is a topic currently under investigation.

In summary, we report here that de-anchoring PKA by st-Ht31 triggers robust cholesterol export preferentially from ABCA1-expressing cells. This effectively reverses macrophage foam cell formation and restores healthy inflammatory response. We speculate that PKA anchoring could be used as a therapeutic target to relieve lipid burden from lesion macrophages and promote lesion regression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jin Zhang (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine) for sharing AKAR constructs and also acknowledge Dr. Yves Marcel (University of Ottawa Heart Institute) for providing bone marrow-derived macrophages.

This work is supported in part by a grant from Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

- ABCA1

- ATP-binding cassette transporter A1

- PKA

- protein kinase A

- apo

- apolipoprotein

- AKAP

- protein kinase A-anchoring protein

- BHK

- baby hamster kidney

- BMDM

- bone marrow-derived macrophage

- PKI

- protein kinase inhibitor

- CFP

- cyan fluorescent protein

- YFP

- yellow fluorescent protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bodzioch M., Orsó E., Klucken J., Langmann T., Böttcher A., Diederich W., Drobnik W., Barlage S., Büchler C., Porsch-Ozcürümez M., Kaminski W. E., Hahmann H. W., Oette K., Rothe G., Aslanidis C., Lackner K. J., Schmitz G. (1999) Nat. Genet. 22, 347–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brooks-Wilson A., Marcil M., Clee S. M., Zhang L. H., Roomp K., van Dam M., Yu L., Brewer C., Collins J. A., Molhuizen H. O., Loubser O., Ouelette B. F., Fichter K., Ashbourne-Excoffon K. J., Sensen C. W., Scherer S., Mott S., Denis M., Martindale D., Frohlich J., Morgan K., Koop B., Pimstone S., Kastelein J. J., Genest J., Jr., Hayden M. R. (1999) Nat. Genet. 22, 336–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Orci L., Montesano R., Meda P., Malaisse-Lagae F., Brown D., Perrelet A., Vassalli P. (1981) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 78, 293–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rust S., Rosier M., Funke H., Real J., Amoura Z., Piette J. C., Deleuze J. F., Brewer H. B., Duverger N., Denèfle P., Assmann G. (1999) Nat. Genet. 22, 352–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Duong P. T., Collins H. L., Nickel M., Lund-Katz S., Rothblat G. H., Phillips M. C. (2006) J. Lipid Res. 47, 832–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nandi S., Ma L., Denis M., Karwatsky J., Li Z., Jiang X. C., Zha X. (2009) J. Lipid Res. 50, 456–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haidar B., Denis M., Marcil M., Krimbou L., Genest J., Jr. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 9963–9969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. See R. H., Caday-Malcolm R. A., Singaraja R. R., Zhou S., Silverston A., Huber M. T., Moran J., James E. R., Janoo R., Savill J. M., Rigot V., Zhang L. H., Wang M., Chimini G., Wellington C. L., Tafuri S. R., Hayden M. R. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 41835–41842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beene D. L., Scott J. D. (2007) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19, 192–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Allen M. D., Zhang J. (2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 348, 716–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Knighton D. R., Zheng J. H., Ten Eyck L. F., Xuong N. H., Taylor S. S., Sowadski J. M. (1991) Science 253, 414–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carr D. W., Hausken Z. E., Fraser I. D., Stofko-Hahn R. E., Scott J. D. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 13376–13382 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Snyder E. M., Colledge M., Crozier R. A., Chen W. S., Scott J. D., Bear M. F. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 16962–16968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hayon T., Dvilansky A., Shpilberg O., Nathan I. (2003) Leuk. Lymphoma 44, 1957–1962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Denis M., Landry Y. D., Zha X. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 16178–16186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Strauss K., Goebel C., Runz H., Möbius W., Weiss S., Feussner I., Simons M., Schneider A. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 26279–26288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Trajkovic K., Hsu C., Chiantia S., Rajendran L., Wenzel D., Wieland F., Schwille P., Brügger B., Simons M. (2008) Science 319, 1244–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fitzgerald M. L., Moore K. J., Freeman M. W. (2002) J. Mol. Med. 80, 271–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Buono C., Anzinger J. J., Amar M., Kruth H. S. (2009) J. Clin. Invest. 119, 1373–1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Groeneweg M., Kanters E., Vergouwe M. N., Duerink H., Kraal G., Hofker M. H., de Winther M. P. (2006) J. Lipid Res. 47, 2259–2267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sethi A. A., Stonik J. A., Thomas F., Demosky S. J., Amar M., Neufeld E., Brewer H. B., Davidson W. S., D'Souza W., Sviridov D., Remaley A. T. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 32273–32282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kinderman F. S., Kim C., von Daake S., Ma Y., Pham B. Q., Spraggon G., Xuong N. H., Jennings P. A., Taylor S. S. (2006) Mol. Cell 24, 397–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Deleted in proof.

- 24. Deleted in proof.

- 25. Zhu X., Lee J. Y., Timmins J. M., Brown J. M., Boudyguina E., Mulya A., Gebre A. K., Willingham M. C., Hiltbold E. M., Mishra N., Maeda N., Parks J. S. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 22930–22941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aiello R. J., Brees D., Bourassa P. A., Royer L., Lindsey S., Coskran T., Haghpassand M., Francone O. L. (2002) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22, 630–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. van Eck M., Bos I. S., Kaminski W. E., Orsó E., Rothe G., Twisk J., Böttcher A., Van Amersfoort E. S., Christiansen-Weber T. A., Fung-Leung W. P., Van Berkel T. J., Schmitz G. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 6298–6303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yvan-Charvet L., Ranalletta M., Wang N., Han S., Terasaka N., Li R., Welch C., Tall A. R. (2007) J. Clin. Invest. 117, 3900–3908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schillace R. V., Miller C. L., Pisenti N., Grotzke J. E., Swarbrick G. M., Lewinsohn D. M., Carr D. W. (2009) PLoS ONE. 4, e4807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.