Abstract

SNF1-related protein kinases 2 (SnRK2s) are plant-specific enzymes involved in environmental stress signaling and abscisic acid-regulated plant development. Here, we report that SnRK2s interact with and are regulated by a plant-specific calcium-binding protein. We screened a Nicotiana plumbaginifolia Matchmaker cDNA library for proteins interacting with Nicotiana tabacum osmotic stress-activated protein kinase (NtOSAK), a member of the SnRK2 family. A putative EF-hand calcium-binding protein was identified as a molecular partner of NtOSAK. To determine whether the identified protein interacts only with NtOSAK or with other SnRK2s as well, we studied the interaction of an Arabidopsis thaliana orthologue of the calcium-binding protein with selected Arabidopsis SnRK2s using a two-hybrid system. All kinases studied interacted with the protein. The interactions were confirmed by bimolecular fluorescence complementation assay, indicating that the binding occurs in planta, exclusively in the cytoplasm. Calcium binding properties of the protein were analyzed by fluorescence spectroscopy using Tb3+ as a spectroscopic probe. The calcium binding constant, determined by the protein fluorescence titration, was 2.5 ± 0.9 × 105 m−1. The CD spectrum indicated that the secondary structure of the protein changes significantly in the presence of calcium, suggesting its possible function as a calcium sensor in plant cells. In vitro studies revealed that the activity of SnRK2 kinases analyzed is inhibited in a calcium-dependent manner by the identified calcium sensor, which we named SCS (SnRK2-interacting calcium sensor). Our results suggest that SCS is involved in response to abscisic acid during seed germination most probably by negative regulation of SnRK2s activity.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, Calcium-binding proteins, Plant, Protein Kinases, Signal Transduction, BiFC, EF-hand, SnRK2, Protein-Protein Interactions

Introduction

Plants respond to environmental stresses by induction of various defense mechanisms. Stress signals are recognized and transmitted to different cellular compartments by specialized signaling pathways in which protein kinases and phosphatases are key components. The SnRK2 family members are plant-specific kinases considered as important regulators of plant response to abiotic stresses. Ten members of the SnRK2 family have been identified in both Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa (1, 2). All of them, except SnRK2.9 from A. thaliana, were shown by transient expression in protoplasts to be rapidly activated by treatment with different osmolytes, such as sucrose, mannitol, sorbitol, or NaCl and some of them also by abscisic acid (ABA),3 suggesting that these kinases are involved in a general response to osmotic stress (1–3). It was also reported that in tobacco BY-2 cells Nicotiana tabacum osmotic stress-activated protein kinase (NtOSAK), a member of the SnRK2 subfamily, is activated rapidly in response to hyperosmotic stress (4–6).

Ample data indicate that SnRK2s are positive regulators of plant response to drought. ABA-activated protein kinase (AAPK) is activated by ABA in guard cells of fava bean (Vicia faba) in response to drought and is involved in the regulation of anion channels and stomatal closure (7). The A. thaliana SRK2E/OST1/SnRK2.6 protein kinase, an enzyme related to ABA-activated protein kinase, has been shown to mediate the regulation of stomatal aperture by ABA and to act upstream of reactive oxygen species production (8). The srk2e mutant cannot cope with a rapid decrease in humidity and has a wilty phenotype. Loss of the kinase function causes an ABA-insensitive phenotype in stomatal closure (9). The Arabidopsis triple mutant snrk2.2/snrk2.3/snrk2.6, also known as srk2d/e/i, disrupted in three ABA-dependent SnRK2s (SnRK2.2/SRK2D, SnRK2.3/SRK2I, and SnRK2.6/SRK2E), is extremely insensitive to ABA and exhibits greatly reduced tolerance to drought, primarily as a result of down-regulation of ABA- and water stress-induced genes (10, 11). The results show that these kinases are major regulators of ABA signaling in response to water stress. The intensity of the triple mutant phenotype is far stronger than that of any of the single or double mutants, indicating that SnRK2.2, SnRK2.3, and SnRK2.6 are to some extent redundant key regulators of the plant response to ABA. Another member of the SnRK2 family in Arabidopsis, SKR2C/SnRK2.8, also plays a significant role in drought tolerance (12). Similarly to SnRK2.2, SnRK2.3, and SnRK2.6, this enzyme is involved in the control of stress-responsive gene expression. It has also been shown that SnRK2.8 is a positive regulator of plant growth, most probably by phosphorylation and regulation of the activity of several enzymes involved in metabolism (13). The results of Diédhiou et al. (14) have revealed that overexpression of SAPK4 (a rice SnRK2) increases rice tolerance to salinity and oxidative stress. SnRK2s have been implicated not only in environmental stress signaling but also in plant development. Recent data reveal that the snrk2.2/2.3/2.6 (srk2d/e/i) triple mutant grows poorly and shows severe defects during seed development. The expression of ABA-induced genes, whose promoters contain an ABA-responsive element, was almost completely blocked in this mutant (10, 11, 15). In vitro studies show that the ABA-activated SnRK2s phosphorylate ABA-responsive element binding factors (16, 17), and this phosphorylation is needed for their transcriptional activity. It is, therefore, suggested that ABA-responsive element binding factors are targets of ABA-dependent SnRK2s (10, 11, 15–19).

Even though it is well established that SnRK2s play a role in the regulation of plant development and abiotic stress signaling, information on the mechanism(s) regulating their activity is still limited. Results presented by several groups provide evidence that phosphorylation in the kinase activation loop is required for SnRK2 activation (6, 20, 21). It has also been shown that group A of PP2C-type protein phosphatases interacts with ABA-dependent SnRK2s and inactivates them efficiently via dephosphorylation of Ser/Thr residues in the activation loop (22, 23). Here, we characterize another potential SnRK2s regulator, a plant-specific calcium sensor SCS, that interacts with the SnRK2 family members in plant cells and participates in inhibition of their activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plant Lines and Growth Conditions

For transient expression experiments protoplasts were isolated from A. thaliana T87 cells or N. tabacum BY-2 cells. Arabidopsis suspension cultures were grown in Gamborg B5 medium as described by Yamada et al. (24); BY-2 cells were grown under conditions described elsewhere (4, 25). Cells were subcultured every 7 days.

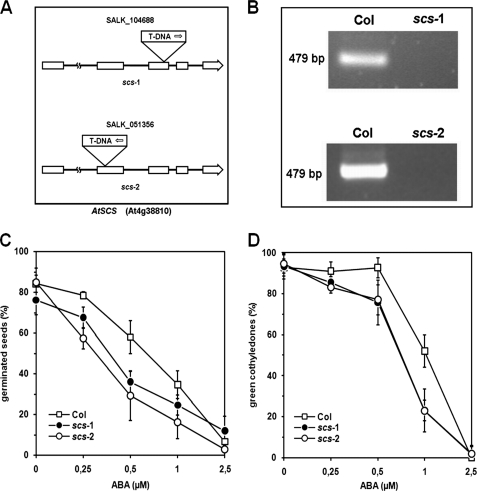

T-DNA insertion lines scs-1 (SALK_051356), and scs-2 (SALK-104688) were obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Center (26). Homozygous plants were selected by PCR screening using specific LP, RP, and left-border LBb1.3 primers. The level of AtSCS expression was analyzed by RT-PCR. All primers used in this study are listed in the supplemental Data 1.

For germination assays, sterilized seeds were sown on ½MS medium with 8 g/liter agar supplemented with ABA at concentration as indicated under “Results.” Plated seeds were stratified at 4 °C for 4 days in darkness. Germination (emergence of radicles) or the presence of green cotyledons was scored 3 or 5 days, respectively, after transferring plates into 16-h light/8-h dark photoperiod at 22/20 °C. All salts and chemicals were from Sigma.

Yeast Two-hybrid Screen and Interaction Assay

The Matchmaker yeast two-hybrid system was used to screen a Nicotiana plumbaginifolia library fused to the Gal4 activation domain for proteins interacting with NtOSAK. The library was kindly provided by Prof. Witold Filipowicz (Friedrich-Miescher Institute, Basel, Switzerland). Yeast plasmids pGBT9 and pGAD424 were from Clontech. Manipulation of yeast cells, transformation, rescue, and library screening were carried out according to standard protocols (Clontech Yeast Protocol Handbook, PT3024-1). The NtOSAK coding region was amplified by PCR with EcoRI and SalI flanking primers (see supplemental Data 1). The resulting PCR product was digested and cloned into pGBT9 to form pGBT9-NtOSAK, which was introduced into the yeast strain PJ69-4a (27). PJ69-4a containing pGBT9-NtOSAK was transformed with the cDNA library and screened for histidine and adenine prototrophy. Plasmids containing cDNA of putative NtOSAK-interacting proteins were isolated from the obtained colonies, and cDNAs were sequenced. To confirm the interaction, the cDNA of the identified NtOSAK-interacting protein (later named NpSCS) was cloned into pGBT9 plasmid, whereas NtOSAK cDNA into pGAD424 and the resulting constructs were retransformed into yeast cells. Interactions between other proteins studied here were analyzed in the same way.

Expression of Recombinant Proteins in Escherichia coli

Full-length cDNAs for SnRK2.4, SnRK2.6, SnRK2.8, and AtSCS, were PCR-amplified using specific primers (listed in supplemental Data 1) and cloned as EcoRI/SalI or BamH1/SalI fragments into pGEX-4T-1 vector (Amersham Biosciences). All PCR reactions were performed using high-fidelity Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and verified by sequencing. cDNAs encoding SnRK2.4, SnRK2.6, and AtSCS (A. thaliana orthologue of NpSCS) obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Center (26) and cDNA encoding SnRK2.8 kindly provided by Prof. D. P. Schachtman (Donald Danforth Plant Science Center, St Louis, MO), were used as templates for PCR. In the case of NpSCS, the EcoRI/EcoRI fragment was cloned into pGEX-4T-1 vector. Additionally, full-length NpSCS cDNA was introduced into plasmid pET-28A (Novagen) to produce a His6-NpSCS fusion protein.

Expression and purification of GST-NtOSAK and GST-SnRK2.8 were performed as previously described (6, 13). Recombinant SnRK2s were expressed overnight in E. coli BL21-DE3 at 18 °C and purified using glutathione-agarose beads (Sigma). Recombinant NpSCS and AtSCS were produced at 37 °C for 2 h and purified using glutathione-agarose beads or nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose beads (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Protein Kinase Activity Assays

The kinase activity assays were performed as described by Mikołajczyk et al. (4), with some modifications.

Aliquots of purified recombinant kinase (about 0.2 μg) or NtOSAK purified from BY-2 cells (about 0.01 μg) were incubated with MBP and/or recombinant AtSCS/NpSCS in a concentration as indicated under “Results” and with 50 μm ATP supplemented with 1 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP in kinase buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mm EGTA, 1 mm DTT, 30 mm MgCl2). To analyze the effect of Ca2+ on the kinase activity, EGTA in the reaction mixtures was replaced with 5 mm CaCl2. The final volume of an incubation sample was 25 μl. After 20 min of incubation at 37 °C, the reaction was stopped by addition of Laemmli sample buffer and boiling for 5 min.

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and phosphorylated substrate was visualized by autoradiography. The kinase activity of NtOSAK purified from BY-2 cells was analyzed by spotting the reaction mixture onto P81 phosphocellulose and washing the filter with 0.85% H3PO4. The radioactivity incorporated into protein was measured by scintillation counting.

Purification of NtOSAK from Tobacco BY-2 Cells

NtOSAK was purified from BY-2 cells treated for 5 min with 250 mm NaCl according to the method described previously (4, 5).

In Vitro Binding Assays

Homogenates of E. coli expressing His6-NpSCS, GST-NtOSAK, or GST as control were used for in vitro binding studies. Protein extracts of His6-NpSCS, GST-NtOSAK, and GST (1 ml containing about 3 mg of protein for each extract) prepared in binding buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 0.005% Tween 20, 1 mm DTT, and 1 mm PMSF) supplemented with either 5 mm CaCl2 or 5 mm EGTA were combined pairwise (His6-NpSCS with GST-NtOSAK and His6-NpSCS with GST as a negative control) (1:1) and incubated at 4 °C with 100 μl of glutathione-Sepharose beads. After gentle rotation for 2 h, at 4 °C the beads were centrifuged and washed three times with the binding buffer. Proteins attached to the resin were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and then by Western blotting using anti-His-tag antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and anti-GST antibodies (Amersham Biosciences).

Immunoblot Analysis

Western blotting was performed as described previously (6). Proteins from crude extracts were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes by tank electroblotting. The membrane was blocked overnight at 4 °C in TBST buffer (10 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) containing 5% bovine serum albumin or 10% (w/v) skimmed milk powder and then incubated for 2 h in TBST buffer with primary anti-His or anti-GST antibodies diluted 1:2000 or 1:5000, respectively. After removing unbound antibodies by extensive washing, the blots were incubated with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody, and the results were visualized by staining with p-nitro blue tetrazolium chloride/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate p-toluidine salt.

Detection of Calcium Binding by 45Ca Autoradiography

45Ca binding was performed according to Maruyama et al. (28). Recombinant proteins were separated on 12% polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto nitrocellulose by tank electroblotting, as described above. The membrane was stained with Ponceau Red, de-stained with water, and soaked in incubation buffer containing 60 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, and 10 mm imidazole-HCl, pH 6.8. The membrane after extensive washing with the above buffer was incubated in the same buffer with the addition of 45CaCl2 (Polonus) to 5 μCi/ml for 10 min. The unbound isotope was removed by washing the membrane with 50% ethanol (4 times for 5 min). The protein-bound 45Ca was visualized by autoradiography.

Calcium Ion Binding Analysis Using Fluorescence Methods

The recombinant protein was purified by reverse-phase HPLC on an analytical ACT Ace C18 column and identified by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry on a Macromass Q-Tof spectrometer (Micromass, Manchester, Great Britain). Protein concentration was determined from UV absorption at 280 nm using the molar extinction coefficient of 10500 m−1 cm−1, calculated for one Trp and three Tyr residues, according to Mach et al. (29). UV absorption spectra were measured on a Cary 3E spectrophotometer (Varian) in thermostated cells of 10-mm path length. In calcium binding experiments, 20 mm Tris buffer, pH 7.4, with 100 mm NaCl was used as a solvent. All measurements were made at 25 °C.

The protein fluorescence was measured using an apparatus described previously (30). The fluorescence of the only tryptophan residue of the protein was excited at 298 nm using a xenon-mercury lamp (Hamamatsu L2482) equipped with a double prism monochromator (M3, Cobrabid). The emission in titration experiments was measured as a total fluorescence signal for λ > 310 nm using a glass filter (UG3, Schott, Jena, Germany) with transmission less than 1% below 310 nm and an R585 (Hamamatsu) photomultiplier working in a single photon counting regime. The fluorescence of all fluorophores of the protein, one tryptophan residue and three tyrosine residues, was excited at 280 nm. The emission was measured as a total fluorescence signal for λ > 295 nm using a glass filter (UG1, Schott, Jena, Germany). In fluorescence titration experiments, small aliquots of concentrated calcium chloride solution were added until the protein fluorescence ceased to change. All protein solutions used in the fluorescence titration experiments were checked for possible calcium contamination by comparing the fluorescence signals of a sample measured in the presence and absence of EDTA.

We measured terbium fluorescence lifetime in water solutions with and without the protein by direct excitation of metal ions at 365 nm (31) in an apparatus described elsewhere (30). The terbium concentration was 1.3 μm, and the protein was 2 μm in 20 mm Tris buffer, pH 7.4 with 100 mm NaCl. Terbium ion fluorescence lifetimes were obtained with a Nucleus Personal Computer Analyzer PCA-II (Tennelec/Nucleus, Inc.) card working in the microchannel scaler mode with 10-μs time resolution. The card was synchronized with a chopper cutting off the exciting light. All fluorescence decays were fitted to a monoexponential function with satisfactory accuracy.

Calcium Ion Binding Constant

The measured fluorescence signal (F) is defined as

where F0 and F1 are fluorescence of the protein without and with the ligand, respectively, and xF and x1 are mole fractions of free protein, PF (without the ligand bound), and the protein with one ligand molecule bound, P1, respectively. The binding constant of the ligand to the protein in the reaction P + L ↔ P1 is defined as

where P0 is the total concentration of the protein, P1 + PF = P0, and L0 is the total concentration of the ligand, LF + P1 = L0. If F′ = F/F0, f1 = F1/F0, x1 = P1/P0, then

The equation is analogous with Equation 8 in Eftink et al. (32) describing single-site ligand binding, where the variables are F′ (from experimental measurements), total ligand concentration L0, and protein concentration P0, and the parameters are the ligand binding constant K1 and relative fluorescence signal f1. Here, the ligand is Ca2+. A two-site model for consecutive calcium binding, Equations 11 and 12 in Eftink et al. (32), was also tried. The parameter values were determined by least-square fitting of theoretical curves to experimental data using the NiceFit program.

Circular Dichroism Measurements

Circular dichroism (CD) experiments were carried out at 25 °C on an Aviv Model 202 spectropolarimeter with a 10-mm path length cuvette. The protein solutions (∼2 μm) were prepared in 5 mm Tris buffer, pH 7.4, with 100 mm NaCl. Spectra were collected with an average time of 3 s for each point and a step size of 1 nm from 198 to 270 nm. All spectra were corrected against the buffer. The data were converted to molar residue ellipticity using the relationship [ϴ] = θ/(10 × n × l × c), where [ϴ] is molar residue ellipticity in (degree cm2 dmol−1), θ is the observed ellipticity in millidegrees, n is the number of amino acid residues in the protein, l is the path length in cm, and c the protein concentration in M. Secondary structure content of the proteins was estimated using the CDNN program (CD spectroscopy deconvolution software) (33).

Protoplast Transient Expression Assay

Protoplasts were isolated and transformed via PEG treatment according to the protocol of He et al. (34) with minor modifications.

After transformation, Arabidopsis T87 protoplasts were suspended in WI incubation solution (0.5 m mannitol, 4 mm MES, pH 5.7, 20 mm KCl), whereas BY-2 protoplasts were transferred into K4 medium (MS salt, MS vitamins, 0.4 m sucrose, xylose 250 mg/liter, 0.1 mg/liter 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, 0.2 mg/liter 6-benzylaminopurine, 1 mg/liter 1-naphthaleneacetic acid) and incubated at 25 °C in the dark for 2 days.

cDNAs encoding NtOSAK, SnRK2.4, SnRK2.6, SnRK2.8, AtSCS, or NpSCS were PCR-amplified using Pfu DNA polymerase and appropriate plasmids constructed for expression of GST fusion proteins listed above as templates, cloned into pCR II-TOPO (Invitrogen), and verified by DNA sequencing. For intracellular localization, the cDNAs were inserted into the pSAT6-EGFP-C1 and, for bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC), into pSAT4-nEYFP-C1 or pSAT4-cEYFP-C1-B. The vectors were provided by Prof. T. Tzfira (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI). Primers are listed in supplemental Data 1.

In each transformation about 2 × 105 protoplasts were transfected with about 40 μg of plasmid DNA; for BiFC experiments the plasmids were mixed in a 1:1 (w/w) ratio. The transfected protoplasts were subjected to 0.3 m sorbitol treatment. In control experiments, water instead of sorbitol was added to the transfected protoplasts. Protoplasts were carefully placed on slides with home-made chambers preventing damage and drying. Fluorescence images were taken with a Nikon EZ-C1 laser scanning microscope mounted on an inverted epifluorescence microscope TE 2000E (Nikon) equipped with a 60× (NA 1.4) oil-immersion objective and Nomarski contrast (differential interference contrast). The 488-nm line from an argon-ion laser (40 milliwatts, Melles Griot) was used for excitation of YFP. YFP fluorescence was detected with a 535/30-nm band-pass filter and rendered in false green. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (H3570, Invitrogen), excited with the 408-nm line from an MOD diode laser (Melles Griot), detected with a 450/35-nm band-pass filter, and rendered in false blue. Differential interference contrast images were acquired using the transmission mode of the EZ-C1 confocal system. The images are z-series projections or single optical sections made with the standard EZ-C1 Nikon software. Images were processed with the EZ-C1 Viewer 3.6 and Adobe Photoshop 6.0 software.

RT-PCR Analysis

RT-PCR analysis was performed as previously described (6). Total RNA was isolated from A. thaliana leaves using TRI REAGENT (MRC, Cincinnati, OH) according to the procedure recommended by the manufacturers. Primers were selected from AtRTPrimer data base (35) and listed in supplemental Data 1.

RESULTS

Putative Calcium-binding Protein Interacts with NtOSAK in the Yeast Two-hybrid System

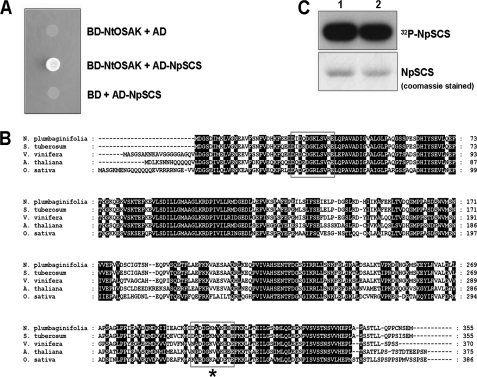

To identify proteins interacting with NtOSAK two-hybrid screening of a N. plumbaginifolia Matchmaker cDNA library was conducted using NtOSAK (GenBankTM accession number AY081175) as bait. The cDNA encoding NtOSAK was fused in-frame with the DNA binding domain of GAL4 in pGBT9 vector, and the obtained construct pGBT9-NtOSAK was transformed into the yeast strain PJ69-4a. The bait plasmid by itself did not activate transcription of reporter genes. Plasmids of the prey library were transformed into the yeast strain expressing NtOSAK, and several positive clones were identified (data not shown). A large proportion of these clones corresponded to the same protein, a putative EF-hand calcium-binding protein, later named by us NpSCS (N. plumbaginifolia SnRK2-interacting calcium sensor). The isolated cDNA encodes a 355-amino acid protein (GenBankTM accession number FJ882981) containing two EF-hand motifs predicted by Prosite; one of them is a classical EF-hand motif with all the conserved residues needed for calcium binding, whereas the other does not completely match the EF-hand consensus sequence. The sequences of the predicted calcium binding loops of NpSCS are shown in Fig. 1. The classical EF-hand motif is a helix-loop-helix structure in which Ca2+ is coordinated by ligands within a 12-residue loop, 7 oxygen atoms from the side chain carboxyl or hydroxyl groups (positions of the EF-hand loop: 1, 3, 5, 12), a main chain carbonyl group (position 7), and a bridged water (via position 9). Residue at position 12 is a bidentate ligand (36). In the same way as calcium, lanthanide ions are coordinated (37). In the second predicted EF-hand motif, position 5 is Gly instead of a residue with a carboxyl or hydroxyl group. Therefore, the second motif probably does not bind calcium ion or binds it weakly.

FIGURE 1.

NtOSAK interacts with putative calcium-binding protein. A, shown is the physical interaction between NtOSAK and NpSCS in a yeast two-hybrid assay. Interaction was monitored by yeast growth on selective medium without adenine and histidine. Yeast were transformed with pGBT9 and pGAD424 plasmids with inserted cDNA encoding NtOSAK and NpSCS, respectively (BD-NtOSAK+AD-NpSCS). As controls, yeast was transformed with one construct containing NtOSAK cDNA and the complementary empty vector (BD-NtOSAK+AD) or plasmid with NpSCS and the other empty vector (BD+AD-NpSCS). Data represent one of three independent experiments showing similar results. B, shown is the amino acid sequence of NpSCS from N. plumbaginifolia (GenBankTM accession number FJ882981) and its orthologues from Solanum tuberosum (CAA04670), Vitis vinifera (CBI37946), A. thaliana (AAL07098), and O. sativa (AAL77132). Predicted EF-hand motifs are boxed; EF-hand-like motif is marked with star (*). Gaps introduced to maximize alignment are marked with dashes. C, NpSCS is phosphorylated in vitro by NtOSAK. GST-NpSCS was expressed in E. coli, purified, and used as substrate in phosphorylation reaction catalyzed by NtOSAK. Incorporation of 32P from [γ-32P]ATP was monitored by gel autoradiography. Upper panel, shown is an autoradiogram. Lower panel, shown is an image of the gel stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R250. Phosphorylation of GST-NpSCS by NtOSAK in reaction buffer with 1 mm EGTA (lane 1) or with 1 mm CaCl2 (lane 2) is shown. Data represent one of three independent experiments showing similar results.

NpSCS is a plant-specific protein; genes encoding its orthologues were found in the genomes of all higher plants that had been completely sequenced and also in lower plants like the moss Physcomitrella patens. In the Arabidopsis genome there is only one member of this family and two in rice. However, function of SCS is still unknown. To confirm NpSCS interaction with NtOSAK, full-length NpSCS cDNA was cloned into the pGBT9 plasmid (BD-NpSCS) and NtOSAK cDNA into pGAD424 (AD-NtOSAK), and the resulting constructs were retransformed into yeast cells. The yeast growth on selective medium confirmed the interaction between the proteins (Fig. 1A). The bait and prey constructs by themselves did not activate expression of the reporter genes, indicating that the two proteins specifically interact in the yeast two-hybrid system (Fig. 1A).

NtOSAK Phosphorylates NpSCS in Vitro

The interaction between NtOSAK and NpSCS indicates that the putative calcium-binding protein can be a substrate of NtOSAK and/or a regulator of its kinase activity. To define a role of this interaction, we first asked whether GST-NpSCS could be phosphorylated by NtOSAK. Our previous studies allowed us to determine the NtOSAK substrate specificity (5). That analysis indicated that a basic residue at position −3 with respect to the phosphorylated Ser/Thr is the main substrate determinant.

Analysis of the NpSCS amino acid sequence indicated Ser-233 and Thr-313, as potential NtOSAK phosphorylation sites. To determine whether NpSCS could be indeed phosphorylated by NtOSAK, an in vitro phosphorylation reaction was performed using NtOSAK purified from BY-2 cells and GST-NpSCS expressed in E. coli. Phosphorylation reaction was conducted in standard phosphorylation conditions elaborated for this kinase (5). We found that GST-NpSCS was phosphorylated by NtOSAK, and the phosphorylation was not dependent on calcium presence (Fig. 1C).

NtOSAK Interacts with NpSCS Regardless of the Presence of Calcium Ions

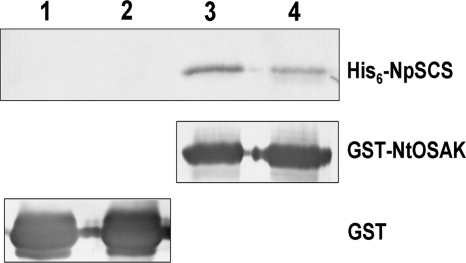

To corroborate the interaction between NtOSAK and NpSCS and to determine whether the binding depends on the presence of calcium, an in vitro pulldown assay was performed. For this purpose, homogenates of E. coli expressing recombinant proteins GST-NtOSAK, His6-NpSCS, and GST (as a control) were used. A homogenate containing His6-NpSCS was mixed with one containing GST-NtOSAK or GST (control) and incubated with glutathione-Sepharose beads with or without CaCl2 (5 mm CaCl2 or EGTA). After incubation followed by extensive washing of the beads, the presence of His-tagged NpSCS bound to GST-NtOSAK or to GST (attached to the beads) was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and then by Western blotting using anti-His antibodies. The level of GST and GST-NtOSAK bound to the beads was analyzed by Western blotting with anti-GST antibodies. As depicted in Fig. 2, NtOSAK and NpSCS were found to interact with each other in vitro both in the presence and absence of calcium ions. The somewhat lower amount of His6-NpSCS bound to GST-NtOSAK in the presence of calcium ions is due to NpSCS degradation under this condition.

FIGURE 2.

NtOSAK interacts with NpSCS in vitro. An in vitro binding assay of His6-NpSCS with GST-NtOSAK (lanes 3 and 4) or GST (as a control) (lanes 1 and 2) attached to glutathione-Sepharose beads is shown. The binding was determined in the absence (lanes 1 and 3) or presence (lanes 2 and 4) of Ca2+ (5 mm CaCl2 or 5 mm EGTA). The presence of bound His6-NpSCS and the amount of GST and GST-NtOSAK bound to the beads were monitored by Western blotting using anti-His tag or anti-GST antibodies, respectively. Data represent one of three independent experiments showing similar results.

NpSCS Binds Calcium Ions

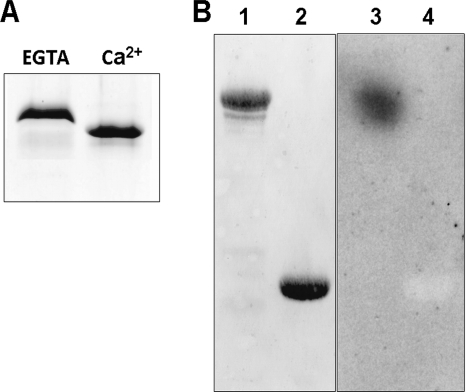

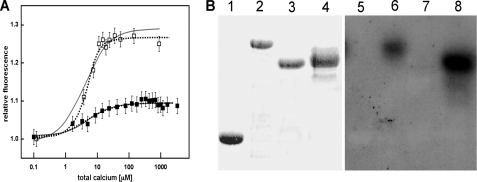

The features of purified recombinant NpSCS protein were examined. The protein was dissolved in a buffer with 5 mm CaCl2 or without calcium ions (with 5 mm EGTA) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The protein migrated differently in the gel depending on the presence of calcium ions in the sample. With CaCl2 it exhibited a specific downward shift characteristic for calcium-binding proteins (Fig. 3A), strongly suggesting that this protein binds Ca2+. The ability of the protein to bind 45Ca2+ was tested in an overlay assay. Purified proteins GST-NpSCS and GST, as a negative control, were separated on SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and the membrane was incubated in a solution containing 45CaCl2 in the presence of 5 mm MgCl2, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” As expected, 45Ca2+ was bound by GST-NpSCS but not by GST (Fig. 3B), thus, indicating that the studied protein does bind calcium ions.

FIGURE 3.

NpSCS binds calcium ions. A, purified NpSCS expressed in E. coli was incubated in buffer without or with Ca2+ (with 5 mm EGTA or 5 mm CaCl2) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Faster migration of NpSCS after incubation with Ca2+ indicates that the protein binds Ca2+ and changes conformation upon Ca2+ binding. B, NpSCS binds 45Ca2+ in an overlay assay. GST-NpSCS (lanes 1 and 3) and GST as control (lanes 2 and 4) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and blotting to a nitrocellulose membrane, and the membrane was incubated in solution with 45Ca2+. After extensive washing, proteins with bound 45Ca2+ were identified by autoradiography of the membrane. Lanes 1 and 2, proteins transferred onto membrane stained with Ponceau S; lanes 3 and 4, autoradiography.

Members of the SnRK2 Family Interact with the Calcium-binding Protein

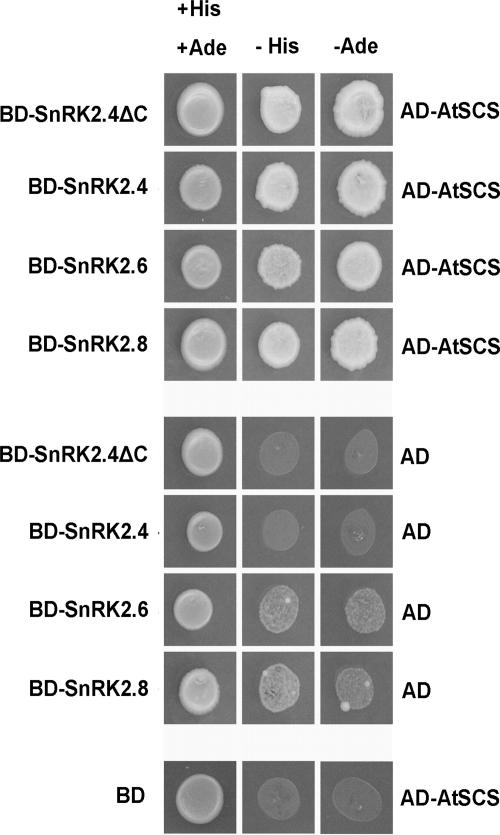

In Arabidopsis and in rice there are 10 members of the SnRK2 family. They can be classified into three groups. According to the Boudsocq and Laurière (3) classification, Arabidopsis group I comprises kinases activated by both osmotic stress and ABA (SnRK2.2, SnRK2.3, and SnRK2.6), group II ABA-independent kinases activated by osmotic stress (SnRK2.1, SnRK2.4, SnRK2.10, SnRK2.5) plus SnRK2.9, which is not activated by osmolytes, and group III kinases activated by osmotic stress and also weakly by ABA (SnRK2.7, SnRK2.8). To check if the identified calcium-binding protein interacts exclusively with NtOSAK or also with other members of the SnRK2 family, we cloned cDNA of NpSCS Arabidopsis orthologue (GenBankTM accession number At4G38810). Full-length cDNA was fused in-frame to cDNA encoding Gal4 activation domain in the pGAD424 yeast expression vector. We also prepared plasmids carrying cDNA encoding SnRK2.4 (from group II, a close homologue of NtOSAK), SnRK2.6 (from group I), and SnRK2.8 (from group III) fused to the DNA binding domain derived from pGBT9 (pGBT9-SnRK2.4, pGBT9-SnRK2.6, and pGBT9-SnRK2.8). Using the two-hybrid system we checked for an interaction between the calcium-binding protein from Arabidopsis and each of the kinases studied. The results revealed that all SnRK2s analyzed interacted with AtSCS (Fig. 4). Additionally, we studied with the two-hybrid system whether SCS forms homodimers in vivo. cDNA encoding AtSCS was introduced into both bait and prey vectors, and protein-protein interaction was analyzed as for the SnRK2-SCS binding studies. No interaction between two AtSCS molecules was detected (Fig. 4). A similar experiment performed with NpSCS showed the same results (data not shown); therefore, we can conclude that SCS does not form oligomeric forms in vivo.

FIGURE 4.

AtSCS interacts with different SnRK2 kinases. Interaction between Arabidopsis SnRK2.4, SnRK2.6, SnRK2.8, and AtSCS was analyzed by yeast two-hybrid assay as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Additionally, interaction of SnRK2.4 without C-terminal regulatory domain (ΔC SnRK2.4) with AtSCS was analyzed. Yeast transformed with a construct bearing cDNA encoding one of the analyzed SnRK2 and complementary empty vector (BD-SnRK2+AD) or a construct bearing AtSCS and the other empty vector (BD+AD-AtSCS) were used as controls. Data represent one of five independent experiments showing similar results.

SCS Interacts with the Kinase Domain of SnRK2

All SnRK2 kinases are low molecular weight proteins of about 40–42 kDa. The N-terminal part is the kinase domain, whereas the C-terminal region with characteristic stretches of acidic residues most probably plays a regulatory role. To determine whether the C-terminal region is involved in the interaction with SCS, we again resorted to the yeast two-hybrid system. SnRK2.4 cDNA fragment encoding the kinase domain of SnRK2.4 (SnRK2.4ΔC, residues 1–315) was fused with Gal4 DNA binding domain. Expression of this construct together with an appropriate empty prey vector did not activate the reporter genes. The construct was used to transform yeast carrying the prey vector with AtSCS. As shown in Fig. 4, AtSCS interacts with the kinase domain of SnRK2.4. Because the kinase domains of all SnRK2s share about 90% identity, this result suggests that most probably also in the case of other SnRK2s, SCS interacts with them through their kinase domains.

Analysis of Calcium Binding Properties of AtSCS

For calcium binding analysis we used fluorescence methods; that is, Tb3+ ion fluorescence lifetime measurements and protein fluorescence titration by Ca2+.

Terbium ion (Tb3+) has been shown to occupy the same binding sites as the Ca2+ ion in many calcium-binding proteins (38). Both ions have an almost identical radius and similar coordination properties. The fluorescence of free terbium ions in water is weak because of the strong quenching by water OH− groups. The fluorescence, however, is enhanced upon protein binding as a result of shielding of terbium from water molecules as well as an energy transfer from nearby aromatic amino acid residues. This allows monitoring of the binding equilibrium and sampling of probable calcium-binding sites. We measured the terbium fluorescence lifetime in water solutions with and without the AtSCS protein. The large increase of the terbium fluorescence lifetime in the presence of the protein against the fluorescence lifetime of free terbium ions, τ = 1040 ± 20 μs versus τ = 550 ± 10 μs, indicates that the protein binds terbium in a specific manner. Moreover, the fluorescence lifetime being close to 1200 μs is consistent with that for Tb3+ bound to EF-hand calcium-binding site (39). The value of τ = 1040 μs, a little less than that characteristic for an EF-hand site, suggests that not all Tb3+ ions were protein-bound. This could be due to a low protein to Tb3+ ratio used in the measurements.

Estimation of the Calcium Binding Constant of AtSCS

The equilibrium constant of Ca2+ binding by AtSCS was determined by Ca2+ titration of the protein fluorescence intensity and a simplex fit of a theoretical curve to experimental data. Ca2+ binding is accompanied by an enhancement of fluorescence intensity. The protein-calcium binding constant, the average of results from several independent experiments for the protein fluorescence excited at 298 nm (monitoring the fluorescence of Trp-182 residue only) and for excitation at 280 nm (monitoring fluorescence of Trp-182 and of Tyr residues Tyr-80, Tyr-139, and Tyr-278) was, thus, calculated at K = 2.5 ± 0.9 × 105 m−1. A theoretical curve for the one-site model of Ca2+ titration of the fluorescence signal, calculated from Equations 1, 2, and 3, with the best-fit parameters K and f found by the Nicefit program, is shown in Fig. 5A. The parameters are K = 3.5 × 105 m−1 and f = 1.29 for excitation at 298 nm and K = 2.6 × 105 m−1 and f = 1.09 for 280 nm excitation. An analysis of the fluorescence data using a simple two-site model of consecutive calcium binding differentiates the fluorescence experiments for excitation at 298 nm from that at 280 nm. The two-site ligand binding model yielded the fit (K1 = 1 × 106 m−1, f1 = 1.05, and K2 = 7 × 104 m−1, f2 = 1.09) with similar accuracy as the single-site model for 280 nm excitation for the fluorescence change of all the protein fluorophores, three tyrosine residues and one tryptophan residue, whereas the fluorescence change of the single Trp-182 is best fitted by the two-site ligand binding model (K1 = 3.5 × 105 m−1, f1 = 1.09 and K2 = 1 × 106 m−1, f2 = 1.27). The parameters for the two-site model are coupled so that determination of all four parameters K1, f1, K2, and f2 using a curve-fitting procedure is not possible without further studies including Ca2+ binding experiments for the two separate calcium-binding sites of the protein (40). Some of those experiments are in progress.

FIGURE 5.

Calcium binding properties of AtSCS. A, calcium ion titration of AtSCS (2.6 μm) results in the rise of the protein fluorescence. Protein fluorescence excited at 298 nm (□) or 280 nm (■) rises with [Ca2+] increasing to reach a maximum at 100 μm Ca2+. The calcium binding constant, calculated from four independent experiments, is K = 2.5 ± 0.9 × 105 m−1. The experimental error was about 2%. A theoretical curve of Ca2+ titration of the fluorescence signal, calculated for a single-site ligand binding model (solid gray line) and two-site model (dotted line) with the best-fit parameters found by the Nicefit program is shown. B, a 45Ca2+ overlay assay is shown. GST-AtSCS (lanes 2 and 6), GST-AtSCS(111–375) (lanes 3 and 7), GST-AtSCS-(1–312) (lanes 4 and 8), and GST as control (lanes 1 and 5) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and blotting to nitrocellulose membrane, and the membrane was incubated with 45Ca2+. After extensive washing, proteins with bound 45Ca2+ were identified by autoradiography of the membrane. Lanes 1, 2, 3, 4, proteins transferred onto membrane stained with Ponceau S; lanes 5, 6, 7, 8, autoradiography.

The Classical EF-hand of SCS Is Involved in Calcium Binding

To prove that the classical EF-hand motif is involved in calcium binding, we performed a 45Ca2+ overlay assay. Purified proteins GST-AtSCS, GST-AtSCS-(1–312) fragment containing only the first predicted EF-hand motifs, GST-AtSCS-(111–375) containing the second putative EF-hand motif, and GST as a negative control were separated on SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and the membrane was incubated with 45CaCl2 as described under “Experimental Procedures.” As expected, 45Ca2+ bound to GST-AtSCS and to the shortened form of GST-AtSCS with the first canonical EF-hand, GST-AtSCS-(1–312), whereas it did not bind or it bound weakly to the N-terminal-truncated GST-AtSCS with the second (putative) EF-hand, GST-AtSCS- (111–375) or by GST (Fig. 5B), thus indicating that the studied protein binds calcium ions, probably through its single classical EF-hand motif.

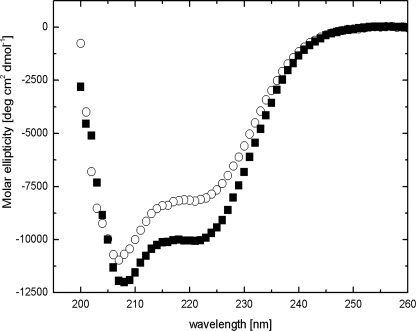

Calcium Influences SCS Conformation

Far-UV CD spectroscopy is commonly used to monitor changes in secondary structure content of proteins; we applied this technique to investigate if calcium binding was accompanied by structural changes of the protein.

The CD spectrum of AtSCS in the apo state (+0.1 mm EDTA) differs from that in the holo state (+0.2 mm Ca2+) (Fig. 6). In the absence of calcium ions, the CD spectrum of the protein indicates an α-helix content of 28%, β-sheet and β-turn content of 38%, and random coil content of 34%, as calculated by the CDNN program (32). Binding of Ca2+ causes a marked increase in the α-helix content of the protein, up to 33%, and a decrease of β-sheet and β-turn content to 34% and of the unordered structure to 33% (Table 1). One may, thus, conclude that the secondary structure of AtSCS changes substantially upon calcium binding.

FIGURE 6.

Conformation of NpSCS changes upon Ca2+ binding. CD spectra of 2 μm AtSCS solution in 5 mm Tris, pH 7.4, with 100 mm NaCl with or without calcium ions are shown. ■, plus 0.1 mm Ca2+ (enough for saturation of Ca2+ binding loop as inferred from fluorescence measurements; Fig. 5A). ○, plus 0.1 mm EDTA.

TABLE 1.

SCS protein secondary structure revealed by CD measurements

The content of secondary structure was calculated by CDNN program (29).

| SCS form | α-Helix | β-Sheet | β-Turn | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | |

| Apo (+0.1 mm EDTA) | 28 ± 1 | 20 ± 1 | 18 ± 1 | 34 ± 2 |

| Holo (+0.2 mm Ca2+) | 33 ± 1 | 17 ± 1 | 17 ± 1 | 33 ± 2 |

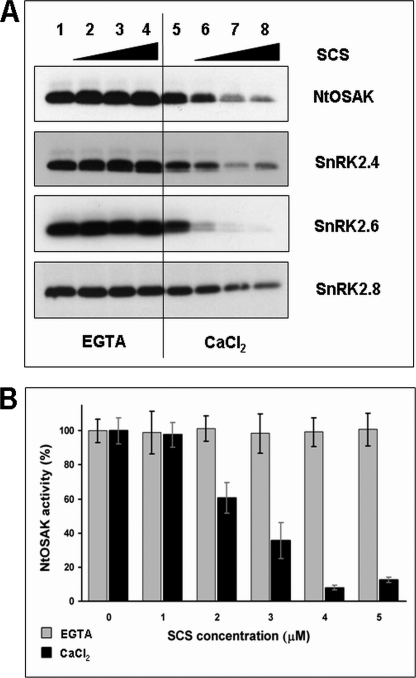

SCS Is a Negative Regulator of SnRK2 Activity in the Presence of Calcium

We tested the effects of NpSCS and AtSCS on the activity of recombinant SnRK2s produced in E. coli, NtOSAK and the Arabidopsis kinases SnRK2.4, SnRK2.6, and SnRK2.8, respectively. The kinase activity was analyzed in vitro by phosphorylation assay with MBP as a substrate. The phosphorylation was carried out in the presence of increasing amounts of NpSCS (for NtOSAK) or AtSCS (for the Arabidopsis kinases) with or without calcium ions in the reaction mixture. The results presented in Fig. 7 show that the kinase activity of all the SnRK2s tested, both ABA-independent and ABA-dependent ones, is negatively regulated by the calcium-binding protein in the presence of Ca2+ ions. However, in the case of all recombinant kinases studied we observed somewhat reduced radioactivity incorporated into MBP when the reaction was performed in the presence of calcium (even without SCS) compared to the conditions with EGTA (Fig. 7A). Therefore, we tested the effect of calcium (up to 5 mm) on phosphorylation of MBP catalyzed by SnRK2 (supplemental Fig. S1). We have observed slightly higher activity of the recombinant kinases in the presence of EGTA; however, the reduction of MBP phosphorylation did not depend on calcium concentration. Moreover, calcium ions have no effect on autophosphorylation of the kinases, which was the same both in presence of EGTA or CaCl2. We have additionally analyzed the effect of SCS on activity of native SnRK2 isolated from plant cells with and without calcium. For this purpose we used NtOSAK purified from tobacco BY-2 cells whose specific activity (about 65 pmol min−1mg−1) is about 100 times higher than that of the recombinant NtOSAK (4, 6) and presumably also than the specific activity of the other SnRK2s produced in the bacterial system. NtOSAK activity is not regulated by calcium in the absence of NpSCS, whereas the inhibitory effect of NpSCS on the kinase activity is in agreement with the qualitative data obtained from analysis of inhibition of the recombinant kinases studied (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 7.

SCS is a calcium-dependent negative regulator of SnRK2 activity. Shown is the effect of SCS on activity of SnRK2 kinases analyzed by in vitro kinase assay. A, kinases studied and SCS from Arabidopsis or tobacco were expressed in E. coli, and kinase activity was measured in presence of increasing amounts of SCS (0, 40, 80, and 160 ng/μl) without or with Ca2+ (5 mm EGTA or 5 mm CaCl2, respectively) in reaction mixture. Kinase activity was monitored using MBP and [γ-32P]ATP as substrates. Reaction products were separated by SDS-PAGE, and MBP phosphorylation was determined by autoradiography. Data represent one of three independent experiments showing similar results. B, NtOSAK was purified from tobacco BY-2 cells (specific activity about 65 pmol min−1mg−1). The kinase activity was analyzed in the presence of increasing amounts of NpSCS (without or with Ca2+). The kinase activity was monitored as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The radioactivity incorporated into protein was measured by scintillation counting. Data represent the mean ± S.E. of four independent experiments.

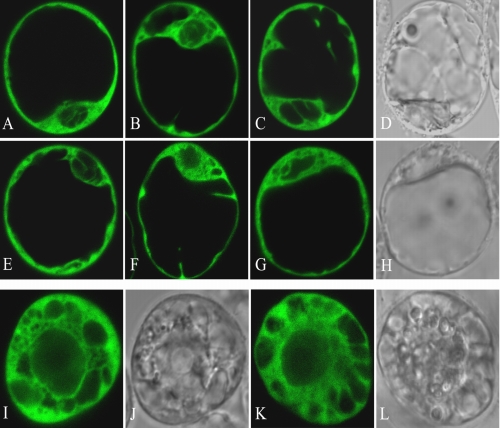

SCS Interacts with SnRK2s in the Cytoplasm

To study the interaction between SnRK2s and SCS in plant cells, we used a transient expression assay. Because the localization of some SnRK2 family members and SCS inside the cell was not known, we decided to determine the subcellular localization of the studied proteins first. The proteins were produced as fusions with EGFP. cDNAs encoding NtOSAK, SnRK2.4, SnRK2.6, SnRK2.8, and Arabidopsis or tobacco SCS were inserted individually into the pSAT6-EGFP-C1 plant expression vector under the control of the tandem cauliflower mosaic virus 35 S promoter. The constructs encoding the tobacco or Arabidopsis proteins as well as a control empty vector encoding EGFP were introduced into tobacco (BY-2) or Arabidopsis (T-87) protoplasts by polyethylene glycol-mediated transfection. As shown in supplemental Fig. S2, the fusion proteins EGFP-NtOSAK, EGFP-SnRK2.4, EGFP-SnRK2.6, and EGFP-SnRK2.8 as well as EGFP-AtSCS and EGFP-NpSCS localized to the nucleus and to the cytoplasm, and their localization was not altered by osmotic stress (300 mm sorbitol treatment). It should be mentioned that none of the proteins studied has a discernible nuclear localization signal. To confirm that an interaction between the proteins studied takes place in planta, we applied BiFC. Appropriate constructs, described under “Experimental Procedures,” encoding each of the studied SnRK2 kinases and SCS (from Arabidopsis or tobacco) fused to complementary non-fluorescent fragments of YFP were introduced into Arabidopsis or tobacco protoplasts, respectively. An interaction of the protein partners should result in reconstruction of a functional YFP protein and its fluorescence. For negative controls, each fusion protein was tested in the presence of the other half of YFP alone (supplemental Fig. S3). Very low fluorescence signal was detectable in the control samples. This signal was comparable with the level of autofluorescence but much weaker than YFP in BiFC samples. The settings of confocal system were the same in all experiments. Our results prove that all analyzed kinases interact with the identified calcium-binding protein in living plant cells, and the interaction occurs exclusively in the cytoplasm (Fig. 8) even though SnRK2.4, SnRK2.6, SnRK2.8, and SCS localize both to the nucleus and the cytoplasm.

FIGURE 8.

SnRK2 kinases interact with SCS in plant cells. Interaction of the proteins was analyzed by BiFC. The interaction led to reconstitution of functional YFP from chimeric proteins bearing non-florescent halves of YFP and its fluorescence. Interactions between AtSCS and SnRK2.4 (A and E), SnRK2.6 (B and F), SnRK2.8 (C and G) in T87 protoplasts not treated (A, B, and C) or treated with 300 mm sorbitol (E, F, and G) are shown. Interactions between NpSCS and NtOSAK in BY-2 protoplasts not treated (I) and treated with 300 mm sorbitol (K) are shown. Images of C, G, I, and K in transmitted light are presented in D, H, J, and L, respectively. Data represent one of several independent experiments showing similar results.

Additionally we applied BiFC for verification of our yeast two-hybrid system data indicating that SCS does not form homodimers. For this purpose we transfected Arabidopsis protoplasts with the pSAT4-nEYFPC1-AtSCS and pSAT4-cEYFPC1-B-AtSCS constructs to check whether AtSCS could dimerize. The lack of YFP fluorescence indicated that SCS does not form homodimers in plant cells (supplemental Fig. S3).

SCS Affects Seed Germination and ABA Sensitivity

Recently, several papers have been published showing that ABA-dependent SnRK2s are involved in the control of stress tolerance, seed development, dormancy, and germination (7, 8, 12, 14). Our results indicated that in vitro SCS inhibits several, most probably all, SnRK2s, and the strongest inhibition was observed for an ABA-dependent kinase (SnRK2.6). Therefore, we analyzed ABA-dependent seed germination of two independent Arabidopsis knock-out mutants (scs-1 and scs-2) in comparison with the wild type Col-0. Wild type and scs T-DNA insertion mutants seeds were sown on plates with ½ MS supplemented with ABA (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2.5 μm). We did not see significant differences in germination rates between lines studied on medium without ABA (Fig. 9C). Seeds of scs mutants were oversensitive to ABA; only 40% of scs-1 and 30% of scs-2 germinated (radicle emergence test) on medium with 0.5 μm ABA, whereas about 60% of Col-0 seeds germinated under the same conditions. Similar differences were observed when the emergence of green cotyledons was scored (Fig. 9D and supplemental Fig. S4). As expected, the phenotype of the scs mutants is opposite that of the snrk2.2/snrk2.3 and snrk2.2/snrk2.3/snrk2.6 mutants. The scs-1 and scs-2 seeds are oversensitive to ABA in the germination assay. The preliminary results suggest that SCS is involved in seed germination, most probably as a negative regulator of SnRK2. At later stages of plant development we do not observe any obvious phenotypic differences between wild type Arabidopsis and the scs mutants under normal growth conditions.

FIGURE 9.

The scs mutants show hypersensitivity to ABA during germination. A, a diagram of AtSCS shows the position of T-DNA insertions. B, RT-PCR analysis of AtSCS expression in wild type Col-0 (Col) and the scs T-DNA insertion mutants (scs-1 and scs-2) is shown. C, radicle emergence in Col-0, scs-1, and scs-2 seeds 3 days after the end of stratification is shown. D, Col-0, scs-1, and scs-2 seedlings with green cotyledons 5 days after the end of stratification is shown. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of six independent experiments, with at least 30 seeds per genotype and experiment.

DISCUSSION

We have previously demonstrated that in response to hyperosmotic stress the activity of NtOSAK is regulated by reversible phosphorylation (6). Now, to identify the NtOSAK regulators or its cellular substrates, we screened the Matchmaker N. plumbaginifolia cDNA library for NtOSAK interactors. A calcium-binding protein was found to strongly interact with NtOSAK. It should be noted that recently two orthologues of this protein were identified in rice as proteins interacting with SnRK2s, but neither their properties nor the physiological meaning of this interaction were analyzed. In that experiment a high-throughput yeast two-hybrid system was applied to build a rice kinase-protein interaction map (41). Genes encoding homologues of this protein have been identified in different plant species, but not in animal genomes, indicating that it is a plant-specific protein. Our results show that the calcium-binding protein interacts with every SnRK2 tested; we studied kinases representing each group of the SnRK2 family according to the classification proposed by Boudsocq et al. (3); SnRK2.6 from group I, SnRK2.4 and NtOSAK from group II, and SnRK2.8 from group III. Our studies revealed that the protein interacting with SnRK2 binds calcium ions (K = 2.5 ± 0.9 × 105 m−1), and its conformation undergoes significant changes upon calcium binding, suggesting that the protein can play a role of a calcium sensor in plant cells. To stress the general character of this interaction we named the protein SCS, SnRK2-interacting calcium sensor. It is plausible that the SnRK2s signaling pathways are closely connected with calcium signaling by the identified calcium sensor. SCS is most likely involved in sensing the fluctuations of calcium ion concentration inside the plant cell and transfers this information via the SnRK2 kinases downstream to effect response to a variety of stimuli.

Calcium is a ubiquitous second messenger in all eukaryotic organisms, including plants. Strong evidence indicates that every stimulus induces a specific calcium ion oscillation in the cytosol with a defined frequency and amplitude, termed “calcium signature.” Specific calcium signatures are generated in plant cells by diverse hormonal and environmental signals, leading to regulation of growth and development, elicitation of plant defense against abiotic and biotic stresses, or induction of programmed cell death (for review, see Refs. 42–45). Specific calcium sensors are involved in decoding each signal. In plants, several hundreds of proteins that potentially bind calcium ions have been identified. A computational analysis of the A. thaliana genome has revealed the presence of 250 EF-hand- or putative EF-hand-containing proteins (45). For most of them, the actual calcium binding properties and function have not been studied. Only about 50 bona fide EF-hand calcium proteins have been characterized so far. According to classification presented by Day et al. (46), SCS belongs to group III of EF-hand-containing proteins. This group contains several proteins involved in abiotic signal transduction in plants, e.g. calcineurin B-like proteins (CBLs) also known as SOS3-like proteins or SCaBPs. These calcium-binding proteins activate CBL-interacting protein kinases (CIPKs), also designated as PKSs, protein kinases related to SOS2. The CIPKs belong to the SnRK3 subfamily of plant SNF1-related protein kinases. Both, the SnRK2 and SnRK3 subfamilies belong to the CDPK-SnRK superfamily (47, 48). Like SnRK2, SnRK3 are plant-specific enzymes involved in regulation of plant responses to abiotic stress. The Arabidopsis genome encodes at least 25 putative CIPK and 10 CBL proteins. Several studies have revealed that each CBL interacts with a subset of CIPKs, and each CIPK interacts with one or more CBLs (for review, see Refs. 49 and 50). Similarly to SnRK2s and SCSs, CBLs and CIPKs have been indentified in all higher plant species whose genomes have been sequenced. However, there is a major difference between the CBL-CIPK and SnRK2-SCS networks; that is, the interaction between CBL and CIPK in the presence of Ca2+ causes activation of the kinase, whereas we report that the activity of SnRK2 is inhibited by SCS in the presence of Ca2+. Earlier studies indicated that calcium ions were required for the CBL-CIPK interaction, but recent crystallographic data suggest that calcium ions are in fact not needed for the complex formation but only for CIPK activation (51). However, it should be mentioned that the function of Ca2+ both in the CBL-CIPK and SnRK2-SCS complexes has only been analyzed in vitro so far. All CBL proteins contain four EF-hand motifs, but only a few contain several canonical EF-hands; two canonical EF-hands are present in CBL1 and CBL9 and one in CBL6, CBL7, and CBL10, whereas CBL2, CBL3, CBL4, CBL5, and CBL8 do not harbor any canonical EF-hand motif (50). This can probably explain the different specificity of each CBL-CIPK complex in decoding various environmental signals resulting in a characteristic calcium signature, although the calcium binding affinity of CBLs has not been determined so far.

SCS has one canonical EF-hand motif and one motif similar to an EF-hand. The results of the fluorescence analysis and 45Ca2+ overlay assay indicate that primarily the canonical EF-hand is involved in calcium binding, but the Ca2+ titration of the protein Trp residue fluorescence also suggested a second calcium-binding site, most probably the atypical EF-hand. It cannot be ruled out that in some circumstances the atypical EF-hand also plays a role in calcium sensing and in specific protein-protein interactions. In our analysis we used SCS proteins expressed in a bacterial system, but one has to bear in mind that the calcium binding properties of SCS can be different in vivo in the presence of SnRK2s and other cellular proteins. Several years ago, based on the structure of SnRK2 kinases, it was predicted that calcium could be somehow involved in their regulation (48). All SnRK2 family members have characteristic acidic C-terminal regions that could play a role in calcium binding. In the case of low affinity, high capacity calcium-binding proteins such as calsequestrin and calreticulin and some bacterial proteins, similar stretches of acidic amino acids are indeed involved in calcium binding (52, 53). Therefore, most probably the acidic C-terminal tails of SnRK2s could cooperate in the calcium binding with specific calcium sensors such as, e.g. SCS.

Our in vitro studies have revealed that the kinase activity of the SnRK2s studied is inhibited by recombinant SCS in a calcium-dependent manner. Because an interaction between SCS and selected SnRK2 kinases was observed both in the yeast two-hybrid system and in plant protoplasts, we suggest that SCS plays a role of a negative regulator of SnRK2 kinases in planta, and its activity depends on a specific calcium signal. We performed some preliminary experiments to establish the role of SCS in vivo. ABA-dependent SnRK2s, SnRK2.2, SnRK2.3, and SnRK2.6 are involved in the control of seed development and dormancy (11, 15). The double snrk2.2/snrk2.3 and triple snrk2.2/snrk2.3/snrk2.6 knock-out mutants exhibit a strong ABA-insensitive phenotype in seed germination (11, 15, and 17). Therefore, we analyzed ABA-dependent seed germination of an scs knock-out mutant in comparison with wild type Arabidopsis. Our results indicate that the scs mutants are ABA-oversensitive in the germination assay. In this aspect the phenotype of scs is just opposite to that of the snrk2.2/snrk2.3 and snrk2.2/snrk2.3/snrk2.6 mutants, suggesting that SCS acts as a negative regulator of SnRK2 not only in vitro but also in vivo. It is highly plausible that by regulating SnRK2 activity SCS affects seed development or maturation, and therefore, we observe oversensitivity to ABA of scs mutants in seed germination assay.

Earlier reports indicate that NO mediates intracellular calcium increase partly through phosphorylation-dependent events sensitive to broad-range protein kinase inhibitors, staurosporine and K252A (54, 55). NtOSAK is activated in response to NO donor treatment (54, 56) and is sensitive to low concentrations of staurosporine (5), and its activation in plant cells is not dependent on Ca2+ influx or Ca2+ release from internal stores (54). Therefore, we can speculate that SnRK2 kinases potentially can be involved in regulation of calcium influx into cytoplasm in response to osmotic stress or ABA. When calcium ions reach an appropriate high level in cytoplasm, SCS binds calcium and participates in turning off SnRK2 activity. Exactly how SCS participates in the calcium-dependent SnRK2 signaling and what are its effects on seed development or dormancy as well as on stress signal transduction awaits further studies. Some of these issues are currently under investigation in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Professor Daniel P. Schachtman and Dr. Ryoung Shin for providing plasmids for SnRK2.8 expression in E. coli and in the yeast two-hybrid system. We thank Professors G. Muszyńska, A. Bierzyński, and J. Fronk for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank the Salk Institute Genomic Analysis Laboratory and Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Center for providing the sequence-indexed Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion mutants and cDNA clones and all members of our laboratory for stimulating discussions.

This work was supported by Ministry of Science and Higher Education Grants N-N301-2540 and 500/N-COST/2009/0 (to G. D.) and European Union Grant COST FA0605.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4 and Data 1.

- ABA

- abscisic acid

- NtOSAK

- N. tabacum osmotic stress-activated protein kinase

- SnRK2

- Snf1-related protein kinase 2

- MBP

- myelin basic protein

- BiFC

- bimolecular fluorescence complementation

- EGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- CBL

- calcineurin B-like protein

- CIPK

- CBL-interacting protein kinase

- SCS

- SnRK2-interacting calcium sensor.

REFERENCES

- 1. Boudsocq M., Barbier-Brygoo H., Laurière C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 41758–41766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kobayashi Y., Yamamoto S., Minami H., Kagaya Y., Hattori T. (2004) Plant Cell 16, 1163–1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boudsocq M., Laurière C. (2005) Plant Physiol. 138, 1185–1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mikołajczyk M., Awotunde O. S., Muszyńska G., Klessig D. F., Dobrowolska G. (2000) Plant Cell 12, 165–178 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kelner A., Pekala I., Kaczanowski S., Muszynska G., Hardie D. G., Dobrowolska G. (2004) Plant Physiol. 136, 3255–3265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burza A. M., Pekala I., Sikora J., Siedlecki P., Małagocki P., Bucholc M., Koper L., Zielenkiewicz P., Dadlez M., Dobrowolska G. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 34299–34311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li J., Wang X. Q., Watson M. B., Assmann S. M. (2000) Science 287, 300–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mustilli A. C., Merlot S., Vavasseur A., Fenzi F., Giraudat J. (2002) Plant Cell 14, 3089–3099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yoshida R., Hobo T., Ichimura K., Mizoguchi T., Takahashi F., Aronso J., Ecker J. R., Shinozaki K. (2002) Plant Cell Physiol. 43, 1473–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fujita Y., Nakashima K., Yoshida T., Katagiri T., Kidokoro S., Kanamori N., Umezawa T., Fujita M., Maruyama K., Ishiyama K., Kobayashi M., Nakasone S., Yamada K., Ito T., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2009) Plant Cell Physiol. 50, 2123–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fujii H., Zhu J. K. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 8380–8385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Umezawa T., Yoshida R., Maruyama K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 17306–17311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shin R., Alvarez S., Burch A. Y., Jez J. M., Schachtman D. P. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 6460–6465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Diédhiou C. J., Popova O. V., Dietz K. J., Golldack D. (2008) BMC Plant Biol. 8, 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nakashima K., Fujita Y., Kanamori N., Katagiri T., Umezawa T., Kidokoro S., Maruyama K., Yoshida T., Ishiyama K., Kobayashi M., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2009) Plant Cell Physiol. 50, 1345–1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Furihata T., Maruyama K., Fujita Y., Umezawa T., Yoshida R., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 1988–1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fujii H., Verslues P. E., Zhu J. K. (2007) Plant Cell 19, 485–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Johnson R. R., Wagner R. L., Verhey S. D., Walker-Simmons M. K. (2002) Plant Physiol. 130, 837–846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kobayashi Y., Murata M., Minami H., Yamamoto S., Kagaya Y., Hobo T., Yamamoto A., Hattori T. (2005) Plant J. 44, 939–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boudsocq M., Droillard M. J., Barbier-Brygoo H., Laurière C. (2007) Plant Mol. Biol. 63, 491–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Belin C., de Franco P. O., Bourbousse C., Chaignepain S., Schmitter J. M., Vavasseur A., Giraudat J., Barbier-Brygoo H., Thomine S. (2006) Plant Physiol. 141, 1316–1327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vlad F., Rubio S., Rodrigues A., Sirichandra C., Belin C., Robert N., Leung J., Rodriguez P. L., Laurière C., Merlot S. (2009) Plant Cell 21, 3170–3184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Umezawa T., Sugiyama N., Mizoguchi M., Hayashi S., Myouga F., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Ishihama Y., Hirayama T., Shinozaki K. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 17588–17593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yamada H., Koizumi N., Nakamichi N., Kiba T., Yamashino T., Mizuno T. (2004) Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 68, 1966–1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nagata T., Nemoto Y., Hasezawa S. (1992) Int. Rev. Cytol. 132, 1–30 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alonso J. M., Stepanova A. N., Leisse T. J., Kim C. J., Chen H., Shinn P., Stevenson D. K., Zimmerman J., Barajas P., Cheuk R., Gadrinab C., Heller C., Jeske A., Koesema E., Meyers C. C., Parker H., Prednis L., Ansari Y., Choy N., Deen H., Geralt M., Hazari N., Hom E., Karnes M., Mulholland C., Ndubaku R., Schmidt I., Guzman P., Aguilar-Henonin L., Schmid M., Weigel D., Carter D. E., Marchand T., Risseeuw E., Brogden D., Zeko A., Crosby W. L., Berry C. C., Ecker J. R. (2003) Science 301, 653–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. James P., Halladay J., Craig E. A. (1996) Genetics 144, 1425–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maruyama K., Mikawa T., Ebashi S. (1984) J. Biochem. 95, 511–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mach H., Middaugh C. R., Lewis R. V. (1992) Anal. Biochem. 200, 74–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dadlez M., Góral J., Bierzyński A. (1991) FEBS Letters 282, 143–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Horrocks W. D., Jr., Schmidt G. F., Sudnick D. R., Kittrell C., Bernheim R. A. (1977) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 99, 2378–2380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eftink M. R. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 278, 221–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Böhm G., Muhr R., Jaenicke R. (1992) Protein Eng. 5, 191–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. He P., Shan L., Sheen J. (2007) Methods Mol. Biol. 354, 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Han S., Kim D. (2006) BMC Bioinformatics 7, 179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kretsinger R. H., Nockolds C. E. (1973) J. Biol. Chem. 248, 3313–3326 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Marsden B. J., Hodges R. S., Sykes B. D. (1989) Biochemistry 28, 8839–8847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brittain H. G., Richardson F. S., Martin R. B. (1976) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 98, 8255–8260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Horrocks W. D., Jr., Rhee M. J., Snyder A. P., Sudnick D. R. (1980) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 102, 3650–3652 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goch G., Vdovenko S., Kozłowska H., Bierzyñski A. (2005) FEBS J. 272, 2557–2565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ding X., Richter T., Chen M., Fujii H., Seo Y. S., Xie M., Zheng X., Kanrar S., Stevenson R. A., Dardick C., Li Y., Jiang H., Zhang Y., Yu F., Bartley L. E., Chern M., Bart R., Chen X., Zhu L., Farmerie W. G., Gribskov M., Zhu J. K., Fromm M. E., Ronald P. C., Song W. Y. (2009) Plant Physiol. 149, 1478–1492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kudla J., Batistic O., Hashimoto K. (2010) Plant Cell 22, 541–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dodd A. N., Kudla J., Sanders D. (2010) Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61, 593–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gilroy S., Trewavas A. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 307–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. DeFalco T. A., Bender K. W., Snedden W. A. (2010) Biochem. J. 425, 27–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Day I. S., Reddy V. S., Shad Ali G., Reddy A. S. N. (2002) Genome Biology 3, RESEARCH0056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hrabak E. M., Chan C. W., Gribskov M., Harper J. F., Choi J. H., Halford N., Kudla J., Luan S., Nimmo H. G., Sussman M. R., Thomas M., Walker-Simmons K., Zhu J. K., Harmon A. C. (2003) Plant Physiol. 132, 666–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Harmon A. C. (2003) Gravit. Space Biol. Bull. 16, 1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Luan S. (2009) Trends Plant Sci. 14, 37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Batistic O., Kudla J. (2009) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1793, 985–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Akaboshi M., Hashimoto H., Ishida H., Saijo S., Koizumi N., Sato M., Shimizu T. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 377, 246–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Beard N. A., Laver D. R., Dulhunty A. F. (2004) Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 85, 33–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Michiels J., Xi C., Verhaert J., Vanderleyden J. (2002) Trends Microbiol. 10, 87–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lamotte O., Courtois C., Dobrowolska G., Besson A., Pugin A., Wendehenne D. (2006) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 40, 1369–1376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sokolovski S., Hills A., Gay R., Garcia-Mata C., Lamattina L., Blatt M. R. (2005) Plant J. 43, 520–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wawer I., Bucholc M., Astier J., Anielska-Mazur A., Dahan J., Kulik A., Wysłouch-Cieszynska A., Zareba-Kozioł M., Krzywinska E., Dadlez M., Dobrowolska G., Wendehenne D. (2010) Biochem. J. 429, 73–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.