Abstract

Sororin is a positive regulator of sister chromatid cohesion that interacts with the cohesin complex. Sororin is required for the increased stability of the cohesin complex on chromatin following DNA replication and sister chromatid cohesion during G2. The mechanism by which sororin ensures cohesion is currently unknown. Because the primary sequence of sororin does not contain any previously characterized structural or functional motifs, we have undertaken a structure-function analysis of the sororin protein. Using a series of mutant derivatives of sororin, we show that the ability of sororin to bind to chromatin is separable from both its role in sister chromatid cohesion and its interaction with the cohesin complex. We also show that derivatives of sororin with deletions or mutations in the conserved C terminus fail to rescue the loss-of-cohesion phenotype caused by sororin RNAi and that these mutations also abrogate the association of sororin with the cohesin complex. Our data suggest that the interaction of the highly conserved motif at the C terminus of sororin with the cohesin complex is critical to its ability to mediate sister chromatid cohesion.

Keywords: Cell Division, Chromosomes, Mitosis, Protein Sequence, Protein-Protein Interactions, Cohesin Complex, Sister Chromatid Cohesion, Sororin, Structure-Function

Introduction

Sister chromatid cohesion ensures accurate segregation of chromosomes and thus is essential to propagation of the genome during growth and development. Cohesion is mediated by cohesin, a large, multisubunit protein complex. The core cohesin complex consists of two large coiled-coil-containing proteins, Smc1 and Smc3, as well Scc1/Mcd1 and Scc3/SA1/2 subunits, and is thought to form a ring-like structure that physically encircles sister chromatids (for review, see Ref. 1).

Several additional proteins are required to modulate cohesin function. The heterodimeric Scc2/Scc4 complex regulates replication licensing-dependent loading of cohesin onto chromatin in telophase in eukaryotes (2, 3). Additionally, the acetyltransferase Eco1/Ctf7 in yeast and the orthologous Eco1 and Eco2 in vertebrates are required for cohesion establishment (4). Recent studies have shown that Smc3 is the relevant substrate for Eco1 acetylation (5–7). The substrate for Eco2 is still unknown. It has been proposed that the acetylation of Smc3 by Eco1 counteracts the “antiestablishment” activity of the WAPL protein (6). Wapl forms a complex with Pds5, a protein that interacts with the cohesin complex (8, 9). Wapl is a negative regulator of cohesion that is thought to destabilize the interaction between the cohesin complex and chromatin during G2 and into prophase (8, 10). WAPL contains several FGF (Phe-Gly-Phe) sequence motifs that mediate interactions both with Pds5 and with the Rad21 subunit of cohesin (9).

Sororin is an essential regulator of sister chromatid cohesion in vertebrates; RNAi of sororin in cultured cells causes loss of cohesion. Sororin was first identified as a substrate of the anaphase-promoting complex (APC)4 and is targeted for degradation in telophase when the APC is activated by the Cdh1 specificity factor (11). Although sororin orthologs can be readily identified throughout the chordate lineage, no obvious orthologs have been identified in lower organisms. Sororin associates with the cohesin complex both in vitro and in vivo and is chromatin-associated during interphase (12, 13). In Xenopus egg extracts, sororin loading onto chromatin is dependent on the cohesin complex, DNA replication, and the Eco2 acetyltransferase (14). The mechanism by which sororin ensures cohesion has not been identified.

In the work presented here we identify regions of the sororin protein required for chromatin binding, interaction with the cohesin complex, and regulation of sister chromatid cohesion. We show that the association of sororin with chromatin is separable from its ability to mediate sister chromatid cohesion. We demonstrate that mutation or deletion of the well conserved C terminus completely abrogates cohesin binding and sister chromatid cohesion.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Sequence Analysis and Alignment

The protein sequence of sororin from several species was scanned for functional and structural motifs using a variety of algorithms available at or through the ExPASy proteomics server of the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, including InterPro Scan, ScanProsite, and PsiPred (15).

Sequences for sororin orthologs were obtained from the NCBI data base. Sequences were aligned with the MegAlign module of the Lasergene 8 Suite (DNAstar, Madison, WI), using the ClustalW algorithm. The consensus sequence was defined as the amino acid most frequently found at that position, where an X indicates no clear majority in the consensus. The consensus strength, defined as the fraction of orthologs with that particular amino acid, is indicated by the height and color of the vertical bars, with the red bars being the most frequent, and dark blue being the least. The overall alignment was scanned for areas with high consensus strength, and boundaries of conserved sequences were drawn manually. Region C was selected manually based on both consensus strength and unusually high lysine content. The accession numbers for the aligned sequences are: dog (Cf; XP_854890), horse (Ec; XP_001491909.1), human (Hs; NP_542399.1), possum (Md; XP_001380073.1), frog (Xl; NP_001088380), zebrafish (Dr; NP_001094417.1). Consensus sequences in text: x, no sequence similarity; −, negatively charged amino acid; p, polar amino acid; and h, hydrophobic amino acid.

Plasmids and Site-directed Mutagenesis

The mu6pro-derived plasmid encoding the shRNA against sororin was described previously (11). Hairpin-insensitive derivatives of sororin were generated by PCR and cloned into a modified version of pCS2 (16). Primers used for each construction are shown in supplemental Tables 1 and 2. Alignment of the mutant proteins is presented in supplemental Fig. 1. For vector controls, both empty pCS2HA and empty mU6pro (17) were used in the same ratios as the derivative constructs.

Antibodies and Immunoblots

Rabbit polyclonal anti-Smc3 antibody was developed against a bacterially expressed fragment encompassing the C-terminal 163 amino acids of human Smc3, and rabbit polyclonal anti-sororin antibody was developed against full-length human sororin expressed in bacteria (Cocalico Biologicals, Reamstown, PA). Antibodies for Nck (NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA) and topoisomerase II (Enzo Life Sciences, formerly StressGen, Plymouth Meeting, PA), and HRP-labeled anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Thermo, Rockford, IL, and Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) were obtained commercially. 12CA5 hybridoma supernatant was used as a source of anti-HA antibody. For immunoblots, samples were resolved on 5–15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with antibodies using standard techniques.

Cell Culture, Synchronization, and Transfection

HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS and 50 mm glutamine. To obtain a population of transfected cells enriched in G2 phase, cells were grown in either 6-well or 10-cm dishes in medium supplemented with 2 mm thymidine for 24 h. Cells were washed to remove thymidine and transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in serum-free medium (Opti-MEM; Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions with either 2 μg of DNA/well (6-well dishes) or 4 μg of DNA (10-cm dishes). Six hours later cells were fed with complete medium supplemented with 2 mm thymidine for 16 h. Thymidine was removed, and the cells were returned to the incubator for 6 h and then harvested. A ratio of 2:1 (shRNA plasmid:pCS2-derived expression construct) was used in all cotransfection experiments.

Chromatin-binding Assay

The chromatin-binding assay was carried out as described by Mendez and Stillman (18). The soluble fraction (S1) and chromatin pellet (P3) as described therein were analyzed.

Sororin Immunoprecipitation Assay

Chromatin was obtained as described above, and the P3 pellet was washed with IP buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.7, 100 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 1 mm DTT, 0.2 mm PMSF) supplemented with 0.1% Triton X-100. Washed pellets were then resuspended in IP buffer supplemented with 0.1% Nonidet P-40 and 2 mm CaCl2 and digested with 2 units/ml micrococcal nuclease (Sigma) for 5 min at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 4 mm EDTA and subjected to a clarifying spin (13,680 × g, 10 min, 4 °C in a Hettich Mikro 220R centrifuge). The supernatant was incubated with anti-HA beads (Roche Applied Science) for 45 min at 4 °C and washed four times with ice-cold IP buffer supplemented with 0.1% Nonidet P-40. Beads were resuspended in SDS sample buffer, boiled for 5 min, and spun briefly. A sample of supernatant equivalent to 10% of the starting material was analyzed by immunoblotting alongside the bead-associated fraction.

Chromosome Spreads

Asynchronously growing HeLa cells were transfected as above and transferred to new dishes after transfection to allow continued growth as necessary. Sixty hours after transfection, cells were harvested with trypsin, washed, and swelled in 0.075 m KCl for 20 min at 20 °C. Cells were pelleted, gently resuspended in ice-cold Carnoy's fix (MeOH:acetic acid 3:1), and incubated on ice for 20 min. Cells were pelleted again and resuspended to a concentration of 5 × 106 cells/ml in Carnoy's fix. Approximately 20 μl of the cell suspension was dropped onto glass slides from a height of 60 centimeters. Slides were air-dried overnight then stained with Giemsa stain (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Slides were analyzed for mitotic index and cohesion phenotypes using a Zeiss AxioImager Z1 upright microscope. Mitotic index (MI) = number of mitotic figures/total number of nuclei, expressed as a percentage of the total population. Color images were collected using a Zeiss AxioImager 2 upright microscope, Zeiss Axiocam MRc camera, and the AxioVision software program (Zeiss; Thornwood, NY).

Image Quantification and Normalization

Immunoblots were processed with secondary antibodies coupled to HRP and visualized with chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce). Data were collected using a Kodak Image Station 4000R and the Kodak Molecular Imaging Software S.E., and quantified using MetaMorph. Background intensity was calculated by averaging pixel intensity of four background regions of each blot. The average background was then subtracted from the integrated intensity of each measured area. The signal obtained from each sororin band was first normalized to the corresponding topoisomerase II band to account for loading differences between samples. The levels of each mutant were then normalized to the sororin:topoisomerase ratio obtained by expression of wild-type sororin to obtain the relative level of chromatin binding for each sororin derivative.

Statistics for Chromosome Spreads

The Fisher's exact two-tailed test was used to determine the significance of the differences between samples.

RESULTS

Identification of Conserved Regions

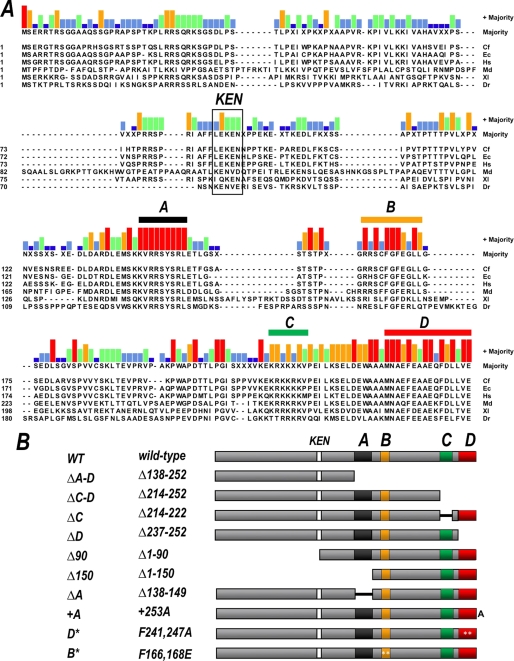

The sororin protein contains no readily identifiable domains or functional motifs. We therefore sought to identify regions of high conservation among sororin proteins from different species, reasoning that these regions are likely to be important for function. Alignment of sororin orthologs from several species indicated that the protein is in fact relatively poorly conserved even among vertebrates, especially compared with most other cohesion proteins (Fig. 1A). Nonetheless, four short stretches of conservation were readily identified. For simplicity, we have arbitrarily named them regions A through D (Fig. 1). They include stretches covering amino acids 138–149 (region A; KVRRSYSRL), amino acids 162–171 containing an invariant FGF motif (region B; SxFGF-xLL), a lysine-rich stretch from amino acids 214 to 222 (region C), and the acidic extreme C terminus of the protein, amino acids 237–252 (region D; MNApF-xAEpF-LhVE) (numbering refers to the human protein sequence). Also indicated in Fig. 1 is the previously described KEN box, which targets sororin for APCCdh1-dependent degradation (11, 19) and thus affects sororin stability in cell cycle-dependent manner.

FIGURE 1.

Identification and mutation of conserved regions in sororin. A, alignment of sororin orthologs from various species. Bar height above the sequence alignment indicates the strength of the consensus at each position, where the consensus is defined as most frequent residue at a given position. Short stretches of high similarity are overlined with colored bars and are arbitrarily named regions A through D. The position of the KEN box degron is also indicated. Cf, Canis familiaris; Ec, Equus caballus; Hs, Homo sapiens; Md, Monodelphis domestica; Xl, Xenopus laevis; Dr, Danio rerio. B, derivatives of human sororin generated based on the alignment shown. Asterisks indicate point mutations, and black connecting lines and spaces indicate deletions. +253A, addition of a single amino acid (alanine) at the extreme C terminus. See supplementary information for details.

To identify potential roles for the conserved regions of sororin, we generated a panel of plasmids encoding human sororin proteins that were mutated by either deletion or mutation of conserved residues (Fig. 1B). Region A was deleted both alone and in combination with other conserved regions as shown. Region B was of particular interest because it contains an invariant FGF sequence. This motif has previously been shown to play an important role in the interaction between Wapl and other cohesion proteins, such as Pds5 and Rad21. To test the role of this sequence directly, we converted the FGF to EGE, because this change in Wapl had been shown to disrupt interactions with its partners (9). Region C comprises a lysine-rich patch, with no strict consensus among species. Finally, region D at the extreme C terminus (arguably contiguous with region C) contains the longest stretch of similarity among species. We noted that all of the sororin proteins terminated with a glutamic acid at precisely the same relative position. To determine whether region D as well as its position relative to the C terminus of the protein is critical to function, we generated both a deletion mutation (ΔD) as well as a construct encoding a single amino acid addition (alanine) at the extreme C terminus (+253A). In a separate construct, we mutated the two invariant phenylalanines in region D (D* = F241,247A). It should be noted that two of the mutants (Δ90 and Δ150) do not contain the KEN box and therefore are predicted to be unaffected by APCCdh1 activity. All derivatives were made from a sororin cDNA with silent mutations in the shRNA target region, which render the messages hairpin-insensitive. Using these constructs it is possible to express the mutant protein and inhibit the expression of the endogenous protein simultaneously, as described previously (11).

Sororin-Chromatin Interaction

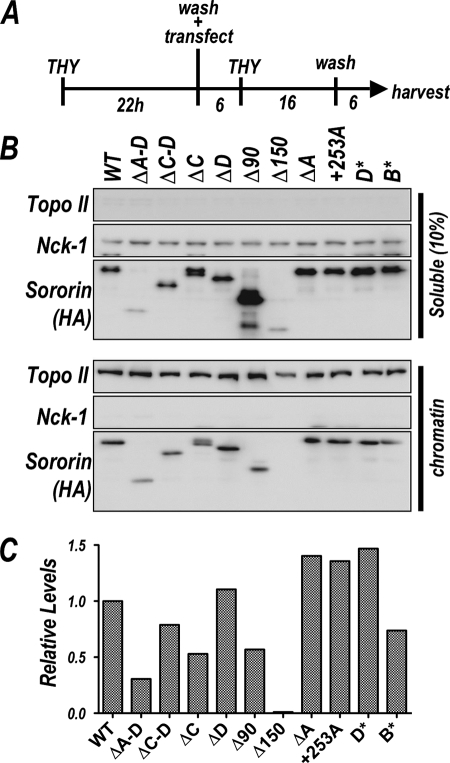

Endogenous sororin binds chromatin throughout interphase (11). Having constructed the panel of sororin mutants, we first tested how the mutations affected the ability of sororin to associate with chromatin. To eliminate the potentially confounding effects of cell cycle perturbation due to cohesion failure over the course of the experiment, cells were synchronized in late S/G2 by double thymidine arrest, as illustrated in Fig. 2A.

FIGURE 2.

Analysis of chromatin association by sororin derivatives. A, schematic illustrates transfection protocol. HeLa cells were arrested with thymidine for 22 h, washed, and transfected with plasmids encoding HA-tagged sororin derivatives. Cells were harvested after release from a second thymidine block to maximize the number of cells in G2. B, samples were processed to separate soluble (upper) and chromatin-associated (lower) proteins and analyzed for sororin by immunoblotting (HA). Nck-1 and topoisomerase II were used as loading controls for soluble and chromatin-bound proteins, respectively. C, data from blot shown in B were quantified. For each sample, levels of sororin were normalized to topoisomerase levels, and this ratio was then compared with that obtained with the wild-type protein, which was set at 1.

We next transfected plasmids encoding hemagglutinin (HA) epitope-tagged versions of the sororin derivatives shown in Fig. 1 and assayed whether the expressed proteins associated with chromatin. Expression of endogenous sororin message was reduced by cotransfection of the shRNA plasmid. The levels of sororin in both chromatin and cytosolic fractions were determined by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 2B).

The use of the same epitope tag on all of the derivatives allowed quantitation of the data because the number of antibody-binding sites is not affected by protein length (Fig. 2C). All of the mutants were overexpressed compared with endogenous protein levels, showed variable total levels of expression, and resulted in unbound (soluble) protein. To avoid the confounding effects of differential expression levels obtained with the different mutants, in our analysis we made the assumption that the sororin-binding sites on chromatin were saturated, and we measured relative binding per unit chromatin by normalizing to topoisomerase levels. As a positive control, HA-tagged wild-type protein was expressed under the same conditions. The binding levels of the HA-tagged wild-type protein were arbitrarily set at 1, and the levels of all other mutant proteins were normalized to this number. Most of the mutant proteins bound chromatin at or near the levels of the wild type. The exceptions are ΔA–D, which generally bound chromatin at a lower level than wild type, and Δ150, which was severely compromised for chromatin binding. It is possible that these two derivatives are relatively unstable because they do not express as well as some of the other variants.

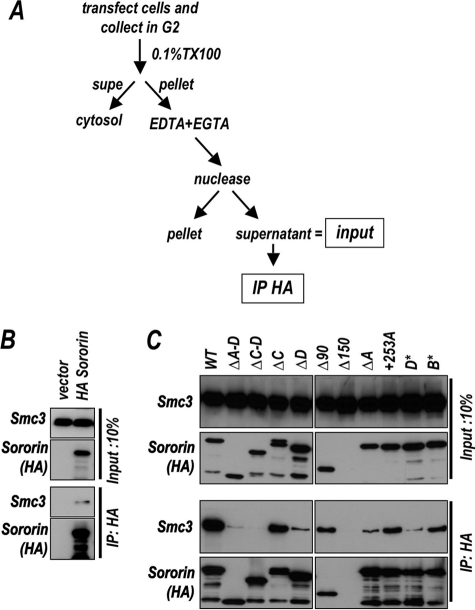

Sororin Association with Chromatin-bound Cohesin

We next tested the ability of mutant derivatives of sororin to interact with the cohesin complex. Sororin associates with the cohesin complex both in vitro and in vivo (11, 13). Because attempts to characterize the interaction between sororin and cohesin in soluble fractions were inconclusive, we decided to probe the interaction on chromatin isolated from late S/G2 phase cells, reasoning that this would reflect the time and site of functional interaction between sororin and the cohesin complex. Again, cells were synchronized and transfected with plasmids encoding HA-tagged sororin derivatives. Cells in G2 phase of the cell cycle were fractionated as illustrated in Fig. 3A. Chromatin-associated sororin was released from the extracted chromatin pellet by nuclease treatment and subject to anti-HA immunoprecipitation.

FIGURE 3.

Coimmunoprecipitation of cohesin with chromatin-associated sororin. A, schematic illustrates method used to obtain chromatin-associated sororin and cohesin. B, chromatin from cells transfected with either a vector control or a vector encoding HA tagged sororin was isolated and extracted as shown in panel A. Lysates were precipitated with anti-HA antibody and the precipitates were analyzed for sororin (HA) and cohesin (Smc3). C, chromatin from cells transfected with sororin derivatives as described in Fig. 2 was treated with micrococcal nuclease to release chromatin bound proteins. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-sororin (HA) antibody bound to beads, and the bead-associated proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting for the presence of both sororin (HA) and cohesin (Smc3). Starting material representing the equivalent of 10% (Input, 10%; top) of the material shown in the immunoprecipitated sample (IP: HA; bottom) is also analyzed.

Immunoprecipitation of HA-tagged full-length sororin from the chromatin of transfected cells resulted in the coprecipitation of cohesin (Fig. 3B). We noted that only a small fraction of the chromatin-associated cohesin was pulled down using this strategy. In the example shown in Fig. 3B, 0.5% of the cohesin was precipitated. We do not yet know what factors affect the efficiency of this reaction, although the results are consistent (n = 6).

We next tested the ability of the panel of sororin derivatives, shown in Fig. 1B, to precipitate the cohesin complex. Again, cohesin coimmunoprecipitated with wild-type sororin, whereas deletion or mutation of the C terminus of sororin abrogated this interaction (Fig. 3C). Specifically, the deletion of region D caused a reduced interaction with the cohesin complex, whereas deletion of both C and D was most reduced for binding (Fig. 3C, bottom panel, third and fifth lanes). Importantly, point mutations in D (D*) also reduced the level of coimmunoprecipitated cohesin, suggesting that this reduction is not simply due to gross misfolding of the deletion mutant. Deletion of region A also reduced interaction with the cohesin complex, although generally not as severely as loss or mutation of region D (Fig. 3C, eighth lane). In the absence of the C terminus, however, region A was unable to mediate any residual cohesin binding, suggesting that this region alone is not sufficient for robust interaction (see ΔC–D). Finally, truncation of the N terminus (Δ90) had no effect on the ability of sororin to precipitate cohesin (Fig. 3C, sixth lane). The Δ150 mutant was not present in the chromatin-associated pool and thus gave a negative result in this cohesin pulldown assay.

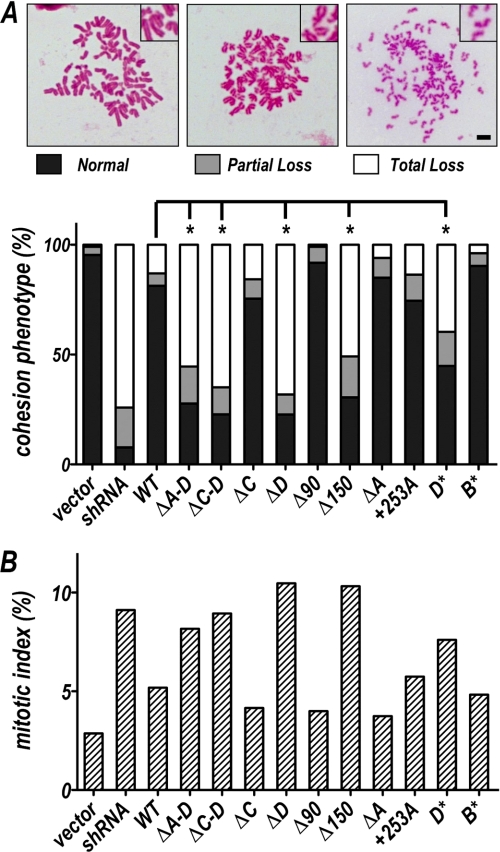

Sororin and Sister Chromatid Cohesion

We utilized a rescue strategy to identify regions of sororin that are critical for sister chromatid cohesion. We showed previously that expression of an shRNA directed against sororin causes cohesion failure in mitotic cells (11). We tested whether expression of the mutant derivatives of sororin described in Fig. 1 could rescue the loss of cohesion caused by shRNA-mediated decrease in sororin levels. To do this, we cotransfected the shRNA-expressing plasmid and plasmids encoding each sororin derivative. Sixty hours after transfection, samples were collected, and chromosome spreads were prepared. Mitotic chromosome spreads were analyzed for cohesion phenotypes, which were scored in one of three categories: normal, in which the arms are paired along the lengths of the sister chromatids and the primary constriction is evident; partial loss of cohesion, where sister chromatid arms are splayed apart or have bubbles or the primary constriction is not evident; and total loss of cohesion, in which no or few paired sisters can be seen, and in many cases chromatids appear hypercondensed (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Rescue of cohesion defects by expression of wild-type and mutant sororin proteins. A, cohesion phenotypes obtained with various sororin derivatives. HeLa cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting the endogenous sororin message as well as plasmids encoding various hairpin-insensitive wild-type and mutant sororin proteins described in Fig. 1. Cells were harvested 60 h after transfection, and chromosome spreads from mitotic cells were assessed for cohesion phenotypes illustrated in photomicrographs at top. The observed cohesion phenotypes, represented as percent total mitotic cells, are shown (n > = 100 mitotic cells in each sample). *, significant difference (p < 0.001; Fisher exact two-tailed test; normal versus aberrant cohesion). The data shown are representative of six experiments with similar outcomes. B, mitotic indices from the same samples tested in A, represented as percent of nuclei showing mitotic morphology. Scale bar, 5 mm.

As shown previously, hairpin-insensitive full-length sororin was able rescue a sororin RNAi phenotype (Fig. 4A). Strikingly, sororin variants with mutations or deletions within the highly conserved C terminus failed to rescue cohesion. For example, ΔD, which lacks only the C-terminal 16 amino acids, was unable to rescue cohesion in this assay. Similarly, D*, in which only the conserved phenylalanine residues within region D are replace by alanines, was also unable to rescue the cohesion defect. In contrast, even a large deletion of the N terminus (Δ90) did not affect cohesion activity. We noted that although the C terminus is critical for function, addition of a single amino acid to the end of the protein did not greatly affect cohesion levels (+253A). Interestingly, the sororin C terminus alone (Δ150) is not sufficient to rescue sister chromatid cohesion. We speculate that this may be due to failure of this mutant protein to bind appropriately to chromatin (see Fig. 2). Mutations within the other conserved regions of the sororin protein, such as a deletion of region A or point mutations in B, did not have strong impact on cohesion activity (ΔA and B*). We conclude from these experiments that the extreme C terminus of sororin mediates sister chromatid cohesion through interaction with the cohesin complex.

Loss of cohesion activates the spindle checkpoint through loss of tension at the kinetochore, causing mitotic arrest and an increase in the mitotic index (for review, see Ref. 20). The mitotic index correlated well with the degree of cohesion failure; cells expressing sororin mutants that were unable to rescue cohesion showed elevated mitotic indices. Rescue of cohesion with wild type or other derivatives restored the low mitotic indices (Fig. 4B).

With the data presented in Fig. 4, we cannot rule out the possibility that the overexpression of sororin in this system prevents our detection of subtle defects in activity. However, the ability to rescue loss of cohesion is a stringent requirement for positive activity, and the inability to complement the phenotype caused by the shRNA strongly implies a loss of function.

DISCUSSION

The mechanism by which sororin regulates sister chromatid cohesion has remained elusive. This has in part been due to the lack of previously characterized functional motifs or structural domains in the protein. Here, we have used a structure-function approach to understand better which regions of sororin are critical for activity. We have identified regions in the protein that are important for association with chromatin, interaction with the cohesin complex, and the ability to mediate sister chromatid cohesion. From these experiments we can draw several interesting conclusions.

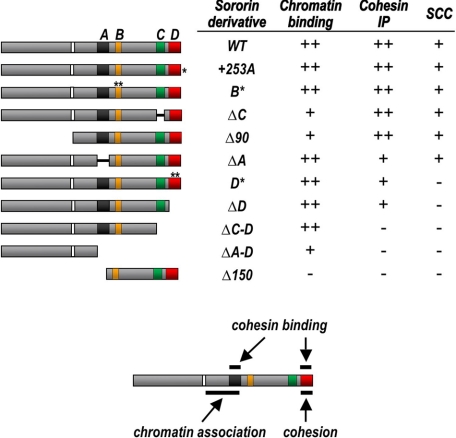

First, our data clearly indicate that the ability of sororin to mediate sister chromatid cohesion is separable from its ability to bind chromatin (see data summary in Fig. 5). Several sororin derivatives presented in this study were inactive for sister chromatid cohesion and unable to bind the cohesin complex, although able to bind chromatin at levels similar to that seen with the wild-type protein. This suggests the interesting possibility that sororin has an additional binding partner, other than the core cohesin complex, on chromatin. For example, sororin may interact with other cohesion factors that modulate the stability of the cohesin-chromatin interaction, such as Eco acetyltransferases or the related Pds5/Wapl complex. It is also possible that sororin interacts with another chromatin-associated protein, such as a replication factor, or perhaps directly with DNA itself. Alternatively, sororin may interact with cohesin through its central region in a manner too weak to survive immunoprecipitation and more strongly through the C terminus. Further investigation is required to distinguish among these possibilities.

FIGURE 5.

Summary. The sororin derivatives are shown sorted in order of degree of defectiveness compared with the wild-type protein, for the assays described in this work. The most defective mutants are shown at the bottom, and proteins with function most similar to wild type are shown at the top. The data indicate that the extreme C terminus of sororin mediates both sister chromatid cohesion and association with the cohesin complex. ++, wild-type levels; −, no apparent activity. Intermediate phenotypes are indicated by +, except for cohesion rescue (SCC, sister chromatid cohesion), which was scored + or −. Bottom, graphical representation of functional map of sororin.

Our data also suggest that sororin-binding sites on chromatin are not saturated under normal conditions. The sororin derivatives characterized in this study, both wild type and mutant, were expressed at levels well over that of the endogenous protein (50–100-fold) and associated with chromatin at levels far above than those that seen for endogenous protein (∼50-fold). Interestingly, even under these conditions we were not able to detect a clear overcohesion phenotype, typically seen as failure to resolve sister chromatids, in cells overexpressing sororin. This suggests that sororin levels are not limiting for maximal cohesion, at least under these conditions. This is in contrast to embryonic extracts, in which overexpression of sororin results in apparent overcohesion defects (11).

Finally, we show that there is a strong correlation between mutant derivatives of sororin that bind cohesin in a pulldown assay and those that are able to rescue loss of cohesion caused by depletion of endogenous sororin. This suggests that interaction of sororin with cohesin, either directly or indirectly, is important for function. This is of course not surprising but had not previously been formally demonstrated. The identity and nature of the sororin-binding site on chromatin are of great interest and will offer insight into the regulation of cohesin stability on chromatin. We have recently shown that sororin recruitment to chromatin requires the cohesin complex, active DNA replication, and the presence of the Eco2 acetyltransferase (14). Together with the data presented here, it seems likely that cohesin modification during DNA replication, presumably by the acetyltransferase, results in development of the sororin-binding site.

The experiments presented here made use of a chromatin extraction procedure to study the interaction between sororin and cohesin. Despite strong effort, we have been unable to detect interaction between soluble cohesin (from cell lysates) and sororin. Attempts based both on addition of recombinant sororin to nuclear extracts and isolation of soluble sororin from somatic cells overexpressing the protein did not suggest any specific interaction with the cohesin complex. We suspect this is because cohesin, and perhaps sororin too, acquires a unique conformation when present on chromatin. The simplest model is that sororin recognizes modified cohesin and that this modification is stimulated during cohesion establishment. We recently demonstrated that the Eco2 acetyltransferase in Xenopus laevis egg extracts is essential for sororin binding, suggesting that sororin binds acetylated cohesin. Eco1, which is not present at significant levels in egg extracts, may also mediate sororin recruitment by a similar mechanism. Because the cohesin complex is also required for sororin recruitment, it is unlikely that sororin itself is a substrate of the acetyltransferase, although this remains a formal possibility. The exact relative contributions of Eco1 and Eco2 to cohesion establishment remain an important and poorly understood aspect of vertebrate chromosome cohesion.

We do not know whether sororin binds cohesin directly or whether other proteins mediate this interaction. Wapl and Pds5, which form a complex that regulates stability of the cohesin-chromatin interaction, are likely candidates for proteins that would mediate an indirect interaction between sororin and the cohesin complex. Future experiments will help to define the relationship between sororin and these proteins, all of which affect the stability of the interaction of cohesin with chromatin in G2.

Structure prediction tools suggest that sororin comprises mostly random coils with a few short helical stretches, making it a member of a class of intrinsically unstructured proteins. Such proteins are often found to perform regulatory roles and have induced folding upon substrate binding, and can bind to multiple partners (21, 22). Future experiments will identify the direct interacting partner(s) of sororin and define the nature of this interesting interaction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Rankin laboratory for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant RR016478 through the NCRR. This work was also supported by Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology Grant HR06-175S.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables 1 and 2 and Fig. 1.

- APC

- anaphase-promoting complex.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nasmyth K., Haering C. H. (2009) Annu. Rev. Genet. 43, 525–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gillespie P. J., Hirano T. (2004) Curr. Biol. 14, 1598–1603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Takahashi T. S., Yiu P., Chou M. F., Gygi S., Walter J. C. (2004) Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 991–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hou F., Zou H. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 3908–3918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rolef Ben-Shahar T., Heeger S., Lehane C., East P., Flynn H., Skehel M., Uhlmann F. (2008) Science 321, 563–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rowland B. D., Roig M. B., Nishino T., Kurze A., Uluocak P., Mishra A., Beckouët F., Underwood P., Metson J., Imre R., Mechtler K., Katis V. L., Nasmyth K. (2009) Mol. Cell 33, 763–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang J., Shi X., Li Y., Kim B. J., Jia J., Huang Z., Yang T., Fu X., Jung S. Y., Wang Y., Zhang P., Kim S. T., Pan X., Qin J. (2008) Mol. Cell 31, 143–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kueng S., Hegemann B., Peters B. H., Lipp J. J., Schleiffer A., Mechtler K., Peters J. M. (2006) Cell 127, 955–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shintomi K., Hirano T. (2009) Genes Dev. 23, 2224–2236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gandhi R., Gillespie P. J., Hirano T. (2006) Curr. Biol. 16, 2406–2417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rankin S., Ayad N. G., Kirschner M. W. (2005) Mol. Cell 18, 185–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rankin S. (2005) Cell Cycle 4, 1039–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schmitz J., Watrin E., Lénárt P., Mechtler K., Peters J. M. (2007) Curr. Biol. 17, 630–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lafont A. L., Song J., Rankin S. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 20364–20369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones D. T. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 292, 195–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Turner D. L., Weintraub H. (1994) Genes Dev. 8, 1434–1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yu J. Y., DeRuiter S. L., Turner D. L. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 6047–6052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Méndez J., Stillman B. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 8602–8612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pfleger C. M., Kirschner M. W. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 655–665 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nezi L., Musacchio A. (2009) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21, 785–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Galea C. A., Wang Y., Sivakolundu S. G., Kriwacki R. W. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 7598–7609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dunker A. K., Brown C. J., Lawson J. D., Iakoucheva L. M., Obradoviæ Z. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 6573–6582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.