Abstract

Neuroinflammation and associated neuronal dysfunction mediated by activated microglia play an important role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease (AD). Microglia are activated by aggregated forms of amyloid-β protein (Aβ), usually demonstrated in vitro by stimulating microglia with micromolar concentrations of fibrillar Aβ, a major component of amyloid plaques in AD brains. Here we report that amyloid-β oligomer (AβO), at 5–50 nm, induces a unique pattern of microglia activation that requires the activity of the scavenger receptor A and the Ca2+-activated potassium channel KCa3.1. AβO treatment induced an activated morphological and biochemical profile of microglia, including activation of p38 MAPK and nuclear factor κB. Interestingly, although increasing nitric oxide (NO) production, AβO did not increase several proinflammatory mediators commonly induced by lipopolyliposacharides or fibrillar Aβ, suggesting that AβO stimulates both common and divergent pathways of microglia activation. AβO at low nanomolar concentrations, although not neurotoxic, induced indirect, microglia-mediated damage to neurons in dissociated cultures and in organotypic hippocampal slices. The indirect neurotoxicity was prevented by (i) doxycycline, an inhibitor of microglia activation; (ii) TRAM-34, a selective KCa3.1 blocker; and (iii) two inhibitors of inducible NO synthase, indicating that KCa3.1 activity and excessive NO release are required for AβO-induced microglial neurotoxicity. Our results suggest that AβO, generally considered a neurotoxin, may more potently cause neuronal damage indirectly by activating microglia in AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer Disease, Amyloid, Neuron, Neuroscience, Potassium Channels, Microglia

Introduction

Aβ,2 a hydrophobic protein derived from proteolytic processing of the amyloid-β precursor protein, self-aggregates into amyloid fibrils and deposits as amyloid plaques, one of the pathological hallmarks of AD. Aβ aggregates, especially those of the 42-residue Aβ42, are potent toxins to neurons. In addition, Aβ aggregates activate microglia, which clear Aβ, but in the process release inflammatory mediators that cause indirect neurotoxicity (1). A commonly held view is that microglia react to fAβ deposited in amyloid plaques, which form a nidus for microglia-mediated neuronal damage. However, because the number of amyloid plaques correlates poorly with the degree of dementia (2, 3), it follows that plaque-associated microglia may not be a major player in cognitive impairment. Emerging evidence including two recent in vivo positron emission tomography studies indicates that microglia may respond to stimuli other than plaque fAβ (4, 5), suggesting that alternative ways to activate microglia must occur in AD.

In addition to fibrillar forms, Aβ exists in various smaller assemblies in AD brains, which may mediate diverse toxic effects at different stages of the disease. Although these smaller aggregates, variously named as oligomers (AβO), protofibrils, amyloid pores, or AD diffusible ligands, have been considered transient or metastable intermediates in fibril formation (6), some of them may not be obligate intermediates in the fibril formation pathway and can be stable (7, 8). Importantly, recent in vitro and in vivo studies have revealed that the build-up of soluble AβO may be an early and central event in the pathogenesis of AD (9–12). The strong and rapidly disruptive effect of AβO on synaptic plasticity and neuronal integrity is hypothesized to cause memory problems in AD and is generally attributed to their direct neuro- or synaptotoxicity (3). However, one plausible but less studied possibility is that AβO activates microglia and causes indirect, microglia-mediated neuro- and synaptotoxicity. However, AβO, at micromolar concentrations, appeared no more potent than fAβ in activating microglia (13–17). In contrast, AβO is much more potent than fAβ in causing synaptic disruption and neuronal death (10, 11, 18, 19).

To examine microglia activators that are pathologically relevant to the development of AD, we investigated the ability of low levels of AβO to activate microglia. Here we report a previously unrecognized AβO effect in activating microglia at 5–50 nm, concentrations that are usually not sufficient to cause direct neurotoxicity. This effect follows a bell-shaped dose-response curve and tapers off at concentrations above 100 nm. Importantly, we show that AβO-activated microglia release NO to cause neuronal damage, and this mode of microglia activation and neurotoxicity is dependent on microglial KCa3.1. Therefore, our data suggest a significant contribution of AβO to microglial neurotoxicity in AD, which may even be more potent than its direct neurotoxicity. This mode of neurotoxicity could be alleviated by inhibitors of KCa3.1 channel activity and NO production.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals

LPS, Congo red (CR), MTT, polyinosinic acid, [3,8-diamino-5-(3-(diethylmethylamino)propyl)-6-phenyl phenanthridinium diiodide (PI), apamin, doxycycline, N-iminoethyl-l-lysine (l-NIL), and N-[(3-aminomethyl)benzyl]acetamidine (1400W) were purchased from Sigma. The CD40 ligand, CD 154, was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). The macrophage colony stimulatory factor was purchased from R & D Systems. The KCa3.1 inhibitor TRAM-34 (1-[(2-chlorophenyl)diphenylmethyl]-1H-pyrazole) was synthesized as described previously (20).

Preparation of Aβ Solutions

AβO solutions as well as the unaggregated and fibrillary Aβ were prepared as described (21). Our preparation of AβO follows the procedure described by Lambert et al. (9) except that the Aβ42 peptide was diluted with Opti-MEM culture medium instead of the F12 medium originally described, before incubation at 4 °C for 24 h to generate oligomers. This preparation of AβO has been extensively characterized in our laboratory (21, 22). To ensure consistency of quality, a random sample from each batch was chosen and imaged using electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy to characterize the size and shape of the aggregates (21–23). The biological activities of each batch were confirmed by determining for AβO the neurotoxic activity, synaptic binding activity, and ability to rapidly induce exocytosis of MTT formazan, as described previously (21, 23).

Soluble AβO from Human Brain Tissue

We obtained hippocampal tissues from three AD subjects and two cognitively and pathologically normal control subjects from the University of California Davis Alzheimer's Disease Center. The use of these samples has been approved by the University of California Davis Institutional Review Board Administration and was reported before (21). All of the subjects had comparable postmortem intervals averaging 5.5 h. Soluble extracts from brain tissues were prepared as described (19, 21, 24). Molecular weight fractionation of oligomeric species was performed using Centricon YM-100 and YM-10 concentrators (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The relative abundance of AβO in the resulting solutions was determined by Western blots using the 6E10 antibody and dot blots using the A11 antibody (25). Although the AD samples contained various amounts of AβO, the two control samples showed no detectable AβO on Western blots and almost background levels on dot blots.

To ensure accurate measurement of the total quantity of Aβ in the extract, we used two Aβ ELISA kits purchased from IBL America (Minneapolis, MN) and Wako Chemicals USA (Richmond, VA), respectively. The procedures were conducted according to manufacturer's protocols.

Primary Cultures

Primary microglia cultures derived from newborn C57BL/6J mice were prepared from mixed glia cultures (1–2 weeks in vitro) with the “shaking off” method as described previously (26). Cultures were ≥99% pure for microglia as demonstrated by anti-IBA1 immunostaining. To obtain conditioned medium (CM) for treating neurons, microglia were first cultured in 24-well culture plates at a density of 1.3 × 105 cells/cm2 for 24 h in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (DMEM10). The cultures were washed extensively and changed to the neurobasal medium with B27 supplement (NB/B27; Invitrogen) without serum and cultured for another 24 h. The NB/B27-based microglia CMs were collected, briefly centrifuged, and used immediately or frozen for future uses.

Hippocampal neuronal cultures were prepared from newborn wild type C57BL/6J mice according to the method of Xiang et al. (27). The neurons were cultured in NB/B27 at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells/well in 12-well plates or 8 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates for at least 14 days before they were treated with microglia CM.

Hippocampal slice cultures (400 μm thick) were prepared from 7-day-old C57BL/6J mice as described previously (26) and cultured for 10 days in vitro before use. Neuronal damage in the slices was monitored by PI uptake following Bernardino et al. (28). PI itself is not toxic to neurons (28). Briefly, hippocampal slices were pretreated with or without doxycycline (20 μm), TRAM-34 (1 μm), 1400W (5 μm), or l-NIL (100 μm) for 1 h and then treated with medium containing PI (2 μm) and AβO of indicated concentration, with or without the above inhibitor compound. After 24 h, the slices were observed under a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope, and the red (630 nm) fluorescence emitted by PI taken up by damaged cells was photographed by a digital camera (SPOT RTke, SPOT Diagnostics, Sterling Heights, MI) with fixed exposure time.

5′-Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdUrd) Incorporation Assay

Microglia were plated onto 48-well culture plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well in DMEM10 and incubated for 24 h. The cells were washed with serum-free Opti-MEM medium three times and treated with the indicated concentrations of AβO in Opti-MEM. After 5 h of incubation, 10 μm BrdUrd was added and allowed to be incorporated into DNA of proliferating cells during an additional 16 h of incubation. The cells with positive BrdUrd incorporation were determined by an immunocytochemical stain for BrdUrd using an anti-BrdUrd antibody conjugated with Alexa594 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol (Chemicon) and counted.

NFκB Assay

The detection of cells with active NFκB was performed according to a previously published method (29). Briefly, microglia were plated as described above and treated with activators for 2 h. The cells were fixed and stained with anti-NFκBp65 antibody (1:250; Chemicon) and with the nuclear dye DAPI.

Assays for Neuronal Viability

Hippocampal neurons were prepared as described above and were plated onto 96-well plate at a density of 6 × 104 cells/well and cultured for 14 days. CM from microglia cultures was added onto neurons with indicated dilutions, and the cultures were incubated for 24 h. Neuronal viability was evaluated by the MTT assay and the lactate dehydrogenase release assay as described previously (22, 26).

Immunofluorescence Staining and Quantification

For immunofluorescent staining of neurons, the cultures were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with anti-PSD95 (1:200; Cell Signaling), anti-MAP2 (1:500; Chemicon), and anti-acetylated α-tubulin (1:250; Zymed Laboratories Inc.). For immunofluorescent staining of microglia, cultures or hippocampal slices were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with anti-IBA1 (1:500; Wako Chemicals USA), anti-SRA (E-20, 1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-CD11b (1:200; AbD Serotec USA, Raleigh, NC). The fixed cells or hippocampal slices were incubated with antibodies overnight at 4 °C followed by secondary Alexa488-conjugated anti-mouse or Alexa568-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (1:700; Molecular Probes). Immunostained images were observed under a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope and photographed by a digital camera (SPOT RTke; SPOT Diagnostics, Sterling Heights, MI).

For quantification of the PSD95-immunoreactive puncta along the dendrites, photomicrographs of PSD95 immunostained cultures were randomly taken from each culture condition. The images were transformed to 8-bit gray scale and analyzed with the Image J program. The number of puncta in each photomicrograph was counted and normalized by dendritic length. The photography and analysis were conducted in an investigator-blinded manner.

Western Blot Analysis

To obtain lysates, cells or tissues were washed with ice-cold PBS and incubated with a buffer containing 50 mmol/liter Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mmol/liter NaCl, 2% SDS, proteinase inhibitor mixture (Sigma), and phosphatase inhibitor mixture (Sigma). The lysates were briefly sonicated and cleared by centrifugation at 50,000 rpm for 10 min. Equivalent amounts of protein were analyzed by Tris-HCl gel electrophoresis. The proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and probed with antibodies. Visualization was performed using ECL (Amersham Biosciences).

The following primary antibodies (dilutions) were used: anti-p38 MAPK (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA), anti-phospho-p38 MAPK (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Synaptophysin (1:1000; Abcam), anti-PSD95 (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-GRIP1 (1:1000; Upstate), anti-MAP2 (1:1000; Chemicon), anti-acetylated α-tubulin (1:2000; Zymed Laboratories Inc.), and anti-β-actin (1:3000; Sigma). Secondary antibodies were HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit, anti-goat, or anti-mouse antibody (1:3000; Amersham Biosciences).

Assay for NO

Conditioned medium collected from microglia cultures (1 × 105/0.75 cm2) and hippocampal slices treated with AβO for 24 h were analyzed by a nitric oxide quantization kit according to the protocol of the manufacturer (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). The data were normalized to the amount of total protein.

Patch Clamp Experiments

Microglia derived from mixed glia cultures (1–2 weeks in vitro) were washed, attached to poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips, and then studied in the whole cell mode of the patch clamp technique with an EPC-10 HEKA amplifier. The pipette solution contained 145 mm K+ aspartate, 2 mm MgCl2, 10 mm HEPES, 10 mm K2EGTA, and 8.5 mm CaCl2 (1 μm free Ca2+), pH 7.2, 290 mOsm. To reduce chloride “leak” currents, we used a Na+ aspartate external solution containing 160 mm Na+ aspartate, 4.5 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 5 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 300 mOsm. K+ currents were elicited with voltage ramps from −120 to 40 mV of 200-ms duration applied every 10 s. Whole cell KCa3.1 conductances were calculated from the slope of the TRAM-34-sensitive KCa current between −80 and −75 mV, where KCa3.1 currents are not “contaminated” by Kv1.3 (which activates at voltages above −40 mV) or inward rectifier K+ currents (which activate a voltages more negative than −80 mV). Cell capacitance, a direct measurement of cell surface area, was continuously monitored during recordings. KCa3.1 current density was determined by dividing the TRAM-34-sensitive slope conductance by the cell capacitance.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaPlot 11 software (Systat Software, Inc). Analysis of variance or repeated-measures analysis of variance was used to compare quantitative values from cultures across groups. Tukey's studentized range test was used to adjust for multiple comparisons in post hoc pairwise tests.

RESULTS

AβO at Low Nanomolar Concentrations Stimulates Microglia into a Distinct Activation Phenotype

Our AβO preparations affected viability of cultured hippocampal neurons at concentrations above 100 nm, consistent with previously published results (22). Interestingly, the same preparations induced proliferation of cultured microglia, starting at 5 nm (22.5 ng/ml) and maximizing at ∼50 nm (225 ng/ml) (Fig. 1, A and B). At 24 and 48 h post-stimulation, cell counts in cultures treated with 20 nm AβO were 184 ± 8.59% (mean ± S.E., n = 6, p < 0.001; Fig. 1D) and 330 ± 21.8% (n = 3, p < 0.001; Fig. 1B) of the values of solvent-treated controls, respectively. The identity of the proliferating cells was confirmed by their immunoreactivity to anti-ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (IBA-1), a microglia-specific marker (Fig. 1A). The mitogenic effect was confirmed by BrdUrd incorporation. Proliferation measured by both cell counting and BrdUrd followed a bell-shaped curve (Fig. 1, B and C), which is very similar to the previously reported chemotactic activity of soluble Aβ for macrophages/microglia that also maximized at low nanomolar concentrations (30). The mitogenic effect was blocked by a neutralizing oligomer-specific antibody A11 (25) and by CR, an amyloid ligand that neutralizes the activity of AβO (21) (Fig. 1D). Because both A11 and CR recognize conformational features but not the primary sequence of Aβ, our results indicate that the conformation of AβO was responsible for the mitogenic effect. The unaggregated Aβ1–42 showed a mild although statistically not significant induction of proliferation (Fig. 1B), attributable to the small amount of AβO invariably formed in aqueous solution because this effect was also blocked by A11 and CR. Fibrillar Aβ and preparations of reverse sequence Aβ peptide (Aβ42–1) up to 500 nm showed no effect (supplemental Fig. S1). These results indicate that at concentrations lower than those required for direct neurotoxicity, AβO is mitogenic for microglia.

FIGURE 1.

Synthetic and human-derived AβO stimulates microglia proliferation at subneurotoxic concentrations. A, microglia were treated with AβO of indicated Aβ concentrations for 48 h. All of the cells in the microglia cultures were stained with Calcein AM. The identity of cells was confirmed by immunostaining with IBA-1, a microglia marker. Cont, control. B, the number of cells in each condition was determined. AβO treatment caused microglia proliferation in a dose-dependent manner, and the effect tapered off at 100 nm. Aβ monomer caused a mild but statistically not significant increase of proliferation. The data presented are the means ± S.E. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001 compared with the 0 nm solvent treatment controls. C, mitogenic assay based on BrdUrd incorporation. AβO treatment caused a dose-dependent incorporation of BrdUrd, following a bell-shaped curve (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001 compared with the 0 nm solvent treatment controls. D, microglia were treated for 24 h with 20 nm AβO or mock-treated with solvent, in the presence of A11 (50 nm), or CR (100 nm), and the cell numbers were determined (n = 5). *, p < 0.001; #, p < 0.05. As a control for the specificity of A11, a rabbit polyclonal antiserum specific for Aβ40 (anti-Aβ40) was also tested and showed no difference from the control. E, soluble extracts with a 10–100-kDa molecular mass cut-off were obtained from AD and control hippocampi. Microglia were treated with these extracts diluted into the medium at indicated percentile (v/v), and the numbers of cells were determined after 24 h. Shown are data from using a representative pair of AD (black bars) and control (white bars) extracts. The actual Aβ42 concentrations (Conc., in nm) for the indicated dilutions of the AD extract are indicated on the x axis (n = 3). *, p < 0.05 for control versus AD in each concentration between the pair of extracts; **, p < 0.001 for 10% AD versus 10% AD + A11 and for 10% AD versus 10% AD + CR.

To determine whether AβO derived from human brain would also promote microglia proliferation, we obtained soluble extracts from hippocampi of AD and age-matched nondemented control subjects. Using Centricon concentrators with molecular mass cut-off between 10 and 100 kDa, we prepared fractions containing AβO but excluding unaggregated Aβ and large aggregates. This preparation of human AβO has been well characterized in previous studies (19, 21, 24, 31). It contains bioactive AβO indistinguishable from synthetic AβO in terms of structure and selective attachment to nerve cell surfaces (21, 24). It contains AβO species recognizable by A11 (21) and a main species at 56 kDa, which is perhaps equivalent to the Aβ42 12-mer oligomers (dubbed Aβ*56) shown to correlate with cognitive deficits in Tg2576 mice (10). We determined the quantities of Aβ in these extracts by sandwich ELISA. Because ELISA may underestimate the total quantity of Aβ when in oligomeric forms (32), we first deaggregated Aβ in the extract with guanidine HCl as described previously (33). In addition, we used two different commercial ELISA kits and obtained consistent Aβ concentrations. Surprisingly, soluble extracts containing AβO from all three AD brains consistently stimulated microglia proliferation at sub-nanomolar to low nanomolar concentrations (∼0.11–1.24 nm Aβ42) (Fig. 1E and supplemental Fig. S2) and thus were ∼50-fold more potent than the synthetic AβO. Parallel treatments of hippocampal neurons with soluble AD brain extracts of the same or higher concentrations did not show any effect on neuronal viability (supplemental Fig. S3). The equivalent fractions from two age-matched control individuals contained little AβO and showed no microglia mitogenic effect. The addition of A11 or CR blocked the mitogenic effect (Fig. 1E), confirming that this effect was mediated by AβO. These results again show that AβO is a potent mitogen for microglia at concentrations that do not cause direct neurotoxicity.

Microglia after synthetic or AD patient brain-derived AβO treatment showed a morphology resembling those activated by LPS or macrophage colony stimulatory factor (Fig. 2A). Biochemical and immunocytochemical evidence also supports that AβO treatment induces an activated phenotype. AβO-treated microglia showed strong up-regulation of MAC-1 (CD11b) and SRA, two markers of microglia activation (Fig. 2A) (34), and increased levels of phosphorylated, therefore activated, p38 MAPK, although the total levels of total p38 MAPK protein were not changed (Fig. 2, B and C). AβO treatment further induced a 6-fold increase of cells showing immunoreactivities of active nuclear factor κB (NFκB, n = 6, p < 0.001; Fig. 2D) (29). This set of cellular responses is qualitatively similar to those induced by LPS activation through the CD14/TLR4 co-receptors, including the stimulation of pathways that are dependent on p38 MAPK and NFκB signaling (26).

FIGURE 2.

AβO (20 nm) treatment induced an activated phenotype of microglia. A, photomicrographs of microglia treated for 24 h with solvent, 20 nm AβO, 50 nm fAβ, 100 ng/ml LPS, and 100 ng/ml macrophage colony stimulatory factor, respectively. B, time course of p38 MAPK activation. A representative set of data is shown. Microglia were treated for 30 min with AβO, AβO with 20 μm doxycycline (Doxy), AβO with 1 μm TRAM-34, or the compound alone. The activation state of p38 MAPK was evaluated by Western blot using an antibody for its phosphorylated epitope. An antibody for p38 MAPK was used to quantify the total p38 MAPK level. The activation of p38 MAPK is represented by the band intensity of phosph-p38 MAPK (p-p38) normalized to that of total p38 MAPK (t-p38). C, quantification from three independent experiments. #, p < 0.001 compared with the 0-min control; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001 compared with the AβO group in the same time point. There was no significant difference between the 0-min control versus AβO + TRAM-34 at any time point. There was no significant difference between AβO versus AβO + doxycycline after 30 min. D, microglia after the indicated treatment for 2 h were immunostained with an antibody for p65 of NFκB to mark cells with NFκB activation. Numbers of p65-immunoreactive cells/200 DAPI-labeled cells were determined. Treatment with AβO and LPS increased the number of cells with activated NFκB (n = 6). *, p < 0.001 compared with control. The AβO-induced activation was prevented by 20 μm doxycycline and 1 μm TRAM-34. **, p < 0.001 compared with the AβO group. LPS-induced activation was prevented by doxycycline. #, p < 0.001 compared with the LPS group but not significantly by TRAM-34. E, nitric oxide (i.e. nitrite) production by microglia after 24 h of indicated treatment was measured in the conditioned medium and normalized by the amount of total cellular protein in each culture. Treatment with AβO and LPS increased microglia NO production (n = 4). *, p < 0.001 compared with control. The AβO- and LPS-induced increase was prevented by 20 μm doxycycline and 1 μm TRAM-34 (n = 4). **, p < 0.001 compared with the AβO group. Doxycycline or TRAM-34 alone did not affect NO production.

Microglia activation is often accompanied by increased release of NO, synthesized by the inducible NO synthase (iNOS) (35). We found that AβO treatment significantly increased NO generation as evaluated by measuring the concentration of nitrite, its stable metabolite, released into the medium (36). After normalization to the total amount of cellular protein, the data indicate an ∼80% increase of NO release/cell; therefore this increase cannot be explained solely by AβO-induced cell proliferation (Fig. 2E). Parallel treatment with Aβ monomer or fibril failed to show any increase in NO (data not shown). Besides NO, however, our initial investigation of several commonly studied neuroinflammatory mediators did not show any AβO-induced increases above basal, sometimes undetectable, levels. These mediators include prostaglandin E2, glutamate, and proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. Parallel microglia cultures treated with LPS showed substantially increased releases of all of these mediators (supplemental Fig. S4). These results suggest that AβO induces a “milder” microglia activation that is significantly different from LPS-induced activation.

AβO-stimulated Microglia Activation Depends on SRA and Can Be Blocked by Doxycycline

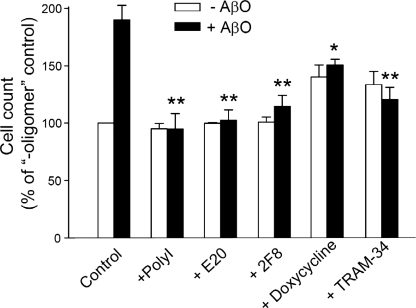

To identify potential targets for pharmacological blockade of AβO-induced microglia activation, we tested several known inhibitors of microglia activation. It was previously shown that scavenger receptors, in particular, SRA, participate in the binding of fAβ (37, 38). Previously we showed that fAβ and AβO share cell surface-binding conformations that can be recognized by amyloid dyes, such as CR (21). Because AβO treatment increased microglial expression of SRA (Fig. 2A), it is possible that SRA may also recognize the amyloid conformation of AβO and mediate at least some of the effects of AβO. Both the general scavenger receptor inhibitor polyinosinic acid and two neutralizing SRA antibodies, E-20 and 2F8 (37), blocked the AβO-induced microglia activation (Fig. 3), suggesting that SRA mediates the interaction of AβO with microglia.

FIGURE 3.

Blockade of AβO-induced microglia activation. Microglia were treated with (black bars) or without (white bars) 20 nm AβO for 24 h in the presence of indicated inhibitors: 100 ng/ml polyinosinic acid, 10 μg/ml anti-SRA antibody E-20 and 2F8, 20 μm doxycycline, or 1 μm TRAM-34 (n = 4). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001 compared with the +AβO control group.

Doxycycline, a second generation tetracycline, has been shown to provide neuroprotection in various models of neuronal injuries by inhibiting microglia activation (39, 40). The reported mechanisms include inhibitions of iNOS, p38 MAPK, and NFκB (41). We found that doxycycline was able to inhibit AβO-induced microglia activation, including NFκB activation and NO generation (Figs. 3 and 2, D and E, and supplemental Fig. S5). Doxycycline also blocked microglia activation induced by human brain AβO (supplemental Fig. S6). Interestingly, doxycycline suppressed the initial (earlier than 30 min) but not the later phase of p38 MAPK phosphorylation following stimulation by AβO (Fig. 2, B and C).

Regulation of AβO-stimulated Microglia Activation by KCa3.1

By modulating Ca2+ signaling, the calcium-activated potassium channel KCa3.1 has been reported to be involved in microglia proliferation, oxidative burst, NO production, and microglia-mediated neuronal killing in rat microglia (42–44). To determine whether our mouse microglia also expressed functional KCa3.1 channels, we studied their K+ channel expression in the whole cell configuration of the patch clamp technique (45). Similar to previous electrophysiological studies of mouse and rat microglia cultured under various conditions (46–49), we observed KCa, KV, and Kir currents. The KV currents exhibited the typical biophysical properties of Kv1.3 and were not studied in detail here. We likewise did not further characterize the Kir currents, which were observed in only a subset of cells. Instead we focused on the KCa currents, which became visible when microglia were dialyzed through the patch pipette with 1 μm of free Ca2+ (Fig. 4A). These currents were clearly not carried by the large conductance KCa channel KCa1.1 (also named BK or maxi-K) because they were voltage-independent as determined by ramp pulses ranging from −100 to +100 mV. The currents further proved insensitive to 100 nm of the KCa2 channel inhibitor apamin (Fig. 4B). However, most of the voltage-independent current component visible during application of voltage ramps from −120 to +40 mV (Fig. 4A) was sensitive to the selective KCa3.1 blocker TRAM-34 (20). The current remaining after perfusion of 1 μm TRAM-34 probably constitutes a combination of Kv1.3, Kir, and another uncharacterized K current. On average, mouse microglia exhibited a KCa3.1 current density of 0.026 pA/pF (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Mouse microglia express the calcium-activated K+ channel KCa3.1. A, scatter plot of TRAM-34-sensitive (KCa3.1) current density and two representative recordings showing the effect of 1 μm TRAM-34. B, the KCa current is insensitive to the KCa2 channel blocker apamin.

Using TRAM-34 as a pharmacological tool, we probed the role of KCa3.1 in AβO-induced microglia activation and neurotoxicity. TRAM-34 alone did not affect microglia viability, as judged by cell count and NO generation (Figs. 2E and 3). TRAM-34 blocked AβO-induced microglia proliferation, p38 MAPK phosphorylation, NFκB activation, and NO generation (Figs. 3 and 2, D–F, and supplemental Fig. S5), suggesting that the AβO effect requires Ca2+ signals maintained by KCa3.1-regulated K+ efflux. TRAM-34 also blocked microglia activation induced by human brain AβO (supplemental Fig. S6). Interestingly, TRAM-34 reduced AβO- but not LPS-induced NFκB activation (Fig. 2E), consistent with a previous study (44) and further indicating the divergent signaling pathways stimulated by AβO and LPS.

AβO Cause Indirect Neuronal Damage via Microglia

Although AβO induced microglia activation at concentrations lower than those required for direct neurotoxicity, we asked whether this activation would result in indirect neuronal damage. To test this possibility, we activated cultured microglia using subneurotoxic concentrations of AβO and transferred the microglia-conditioned medium (AβO-CM) to cultured hippocampal neurons. As negative controls, we treated neurons with CM derived from microglia mock-treated with solvent (Con-CM) and medium with AβO not conditioned by microglia. As positive controls, we treated neurons with CM derived from microglia treated with LPS (26). Fig. 5 shows that AβO-CM significantly reduced neuronal viability in a dose-dependent manner. Con-CM also caused mild neurotoxicity at high concentrations, but the toxicity was much less than that exerted by AβO-CM. In contrast, the equivalent amount of AβO directly added to the medium without being conditioned by microglia did not reduce neuronal viability. Independent experiments using the lactate dehydrogenase release assay for cell death showed similar results (supplemental Fig. S7). This indirect neurotoxic effect of AβO is still significant even after normalization by microglia cell number, which increased ∼1.8-fold after AβO treatment. The AβO-CM-mediated neurotoxicity was not blocked by adding A11 or CR to the neuron cultures (data not shown), further supporting that it was not due to residual AβO in CM.

FIGURE 5.

AβO caused indirect, microglia-mediated neurotoxicity. Hippocampal neurons, 14 days in vitro, were treated with three kinds of media diluted into the neuronal culture medium at the indicated percentiles for 24 h. They are (i) medium with direct addition of AβO (20 nm) but without conditioned by microglia (+AβO), (ii) medium previously conditioned by unstimulated microglia (+Con-CM), (iii) medium previously conditioned by AβO (20 nm)-stimulated microglia (+AβO-CM), and (iv) medium previously conditioned by LPS (100 ng/ml)-stimulated microglia (+LPS-CM). Neuronal viability was evaluated by the MTT assay (n = 3; except n = 1 for the LPS-CM group). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001; ***, p < 0.0001 compared with the control (no addition) group. #, p < 0.05; ##, p < 0.001 when compared with the +Con-CM values of the same dilution of microglia CM.

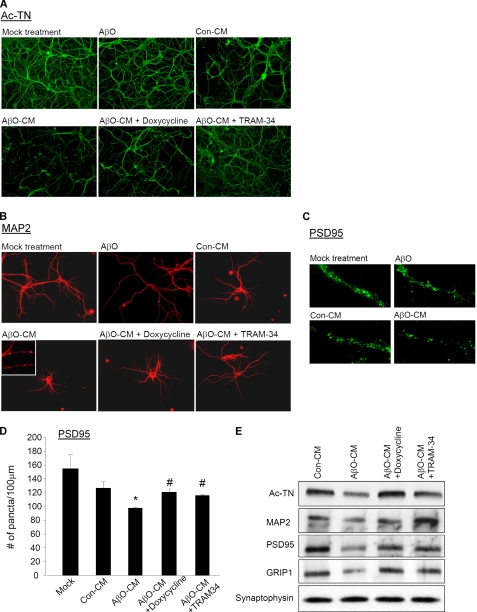

Because dendritic and synaptic damage likely play a more important role than neuronal loss in the early stages of AD, we asked whether AβO could enhance the ability of microglia to damage dendrites and synapses. We found that neurons treated with AβO-CM showed much more robust signs of dendritic damage than those treated with Con-CM, as demonstrated by immunofluorescent stains with two dendritic markers: acetylated tubulin (Ac-TN) and microtubule associated protein 2 (MAP2) (Fig. 6, A and B). Dendrites of AβO-CM-treated neurons were thinner and shorter, with significantly stunted arborization and frequently fragmented or “beaded” appearance (50), best illustrated by sparsely plated neurons (Fig. 6B). Treatments with AβO-CM also substantially reduced the number of PSD95-immunoreactive puncta, which represent the PSD of excitatory synapses (Fig. 6, C and D). Western blots of neuronal extracts revealed that treatments with AβO-CM resulted in reduced levels of Ac-TN, MAP2, PSD95, and another scaffolding protein in the postsynaptic compartment called glutamate receptor-interacting protein 1 (GRIP1) (51) but not the presynaptic marker protein synaptophysin (Fig. 6E; for quantification, see supplemental Fig. S8). In contrast, adding the low nanomolar amount of AβO directly to the hippocampal neuron cultures did not cause a significant reduction of postsynaptic proteins (Fig. 6, A–C).

FIGURE 6.

AβO caused indirect, microglia-mediated damage to dendrites and synapses. The levels of dendritic and synaptic markers were compared between hippocampal neurons treated with solvent only (mock treatment), 20 nm AβO, Con-CM, AβO-CM (see Fig. 5), or CM from microglia cultures in which AβO-induced activation was inhibited by doxycycline (AβO-CM + doxycycline) or TRAM-34 (AβO-CM + TRAM-34), for 24 h. All of the CM used were diluted at 12.5% into the neuronal culture medium. A, dendrites were demonstrated by immunostaining for Ac-TN (green). B, for better visualization of individual dendrites, dendrites of the sparsely plated neurons were demonstrated by immunostaining for MAP2 (red). The inset contains a magnified image showing the “beaded” appearance of dendrites of AβO-CM-treated neurons. C, PSD95-immunoreactive puncta (green) along representative segments of dendrites. D, The mean counts of PSD95-immunoreactive puncta per unit (100 μm) length. AβO-CM treatment significantly reduced the PSD95 count (n = 3). *, p < 0.001 compared with the Con-CM group. This reduction was prevented by inhibition of microglia activation by 20 μm doxycycline or 1 μm TRAM-34 (n = 3). #, p < 0.001 compared with the AβO-CM group. E, Western blot analysis of lysates from neurons with indicated treatment, analyzed by antibodies to dendritic proteins Ac-TN and MAP2, postsynaptic proteins PSD95 and GRIP1, and presynaptic protein synaptophysin.

To confirm that the indirect neurotoxicity was a consequence of microglia activation by AβO, we tested whether blocking AβO-induced microglia activation by doxycycline or TRAM-34 also blocks the indirect neurotoxicity. CM from AβO-treated microglia co-incubated with doxycycline or TRAM-34 did not alter the dendritic morphology (Fig. 6, A and B) and did not cause significant decreases in levels of Ac-TN, MAP2, PSD95, and GRIP1 (Fig. 6, D and E). The lack of KCa3.1 expression in neurons (45, 52, 53) makes it unlikely that the above neuroprotective effect was due to a direct effect of residual TRAM-34 in transferred CM on neurons. Taken together, these results indicate that AβO at subneurotoxic concentrations damage dendrites and synapses by an indirect, microglia-mediated mechanism.

AβO Induces Neurotoxicity via Activating Microglia in Organotypic Hippocampal Slices

We further tested the AβO effect on microglia using organotypic hippocampal slice cultures, which would better reflect the conditions in the brain in terms of microglial density and their interaction with astroglia and neurons. Treating hippocampal slices with 5–50 nm AβO caused a significant increase in cells immunoreactive for SRA and CD11b, markers for activated microglia (Fig. 7A). AβO treatment resulted in a transformation of microglia into an activated morphology with retracted processes and enlarged cell bodies (Fig. 7A). Microglia activation was blocked by co-treatment with A11 antibody, confirming that this effect was due to AβO (Fig. 7A). The CM after the treatment contained increased levels of NO (Fig. 7B). AβO treatment did not increase the release of glutamate, prostaglandin E2, TNF-α, IL-1β, or IL-6 (supplemental Fig. S9), consistent with our findings using dissociated microglia cultures. Parallel treatments with unaggregated and fibrillar Aβ did not induce microglia activation.

FIGURE 7.

AβO activated microglia and caused indirect, microglia-mediated neurotoxicity in hippocampal slices. The treatment consisted of 20 nm AβO for 24 h. A, hippocampal slices were treated as indicated and stained with Hoechst to outline the slices and with anti-CD11b (green) and anti-SRA (red) to evaluate microglia activation. AβO treatment caused increased staining of CD11b and SRA. A magnified image from an outlined SRA-immunoreactive area is shown on the far right to demonstrate the activated morphology of microglia. B, NO production was measured as nitrite level in the conditioned medium as described in Fig. 2E and normalized to the amount of total protein of the slice. Treatment with AβO and LPS increased NO production from hippocampal slices (n = 4). #, p < 0.001 compared with the control group. The AβO-induced increase was prevented by 20 μm doxycycline and 1 μm TRAM-34 (n = 4). *, p < 0.05 compared with the AβO group. Doxycycline or TRAM-34 alone did not affect NO production. C, paired consecutive slices received the same indicated treatment. One slice was then used for PI uptake study for neuronal damage, and the other for CD11b staining for microglia activation. There was low background PI uptake and CD11b staining in the control slices. AβO significantly enhanced PI uptake and CD11b staining, which were ameliorated by doxycycline and TRAM-34. The locations of hippocampal subfields CA1, CA3, and dentate gyrus (DG) are indicated. D, Western blot analysis of lysates from hippocampal slices with indicated treatment, analyzed by antibodies to dendritic proteins Ac-TN and MAP2, postsynaptic proteins PSD95 and GRIP1, and the presynaptic protein synaptophysin.

The uptake of the fluorescent dye propidium iodide (PI) is frequently used to monitor neuronal damage in slice cultures (28, 54). AβO treatment resulted in significantly increased uptake of PI by neurons of all hippocampal subfields, a pattern approximating the pattern of microglia activation, although the distribution of activated microglia was broader, extending outside the neuronal domains (Fig. 7C). By co-staining the slices used for PI uptake assay for the neuronal marker NeuN, we further showed substantial NeuN immunoreactivity in nuclei that had taken up PI, indicating neuronal damage (Fig. 8D and supplemental Fig. S11). Western blotting demonstrated that AβO treatment also resulted in significant damage to post-synaptic elements, as demonstrated by reduced levels of Ac-TN, MAP2, PSD95, and GRIP1 but not the pre-synaptic marker synpatophysin (Fig. 7D; for quantification, see supplemental Fig. S10).

FIGURE 8.

NO mediates AβO-induced microglial neurotoxicity. A, NO production was quantified as described for Fig. 2E. The AβO-induced increase was prevented by 5 μm 1400W and 100 μm l-NIL (n = 3). *, p < 0.01 compared with the AβO group. B, AβO-induced microglial neurotoxicity was evaluated as described for Fig. 5. Control or AβO-treated microglia cultures were at the same time treated with vehicle, 1400W, or l-NIL for 24 h. Hippocampal neuron cultures were then treated with 25% CM from each microglial culture. Neuronal viability was determined after 24 h. Both 1400W and l-NIL blocked the AβO-induced microglial neurotoxicity (n = 3). *, p < 0.001 compared with the AβO-CM/vehicle group. C, NO released by hippocampal slices was measured as described in Fig. 7B. Both 1400W and l-NIL blocked AβO-induced NO production (n = 3). *, p < 0.001 compared with the AβO group. D, hippocampal slices were treated with the indicated conditions, and the PI uptake assay was performed as described for Fig. 7C. The same slices were then immunostained with NeuN that marked neuronal nuclei (NeuN, green; PI uptake, red). A magnified image from an outlined area in the CA1 region of the AβO-treated hippocampal slice is shown on the right upper panel to demonstrate the substantial colocalization of NeuN immunoreactivity and PI fluorescence. Both 1400W and l-NIL blocked AβO-induced neuronal damage as indicated by significantly reduced PI uptake.

To determine whether the neurotoxic effects of low nanomolar AβO were indeed mediated by activation of microglia, we again tested doxycycline and TRAM-34 for their ability to block toxicity to neurons. AβO-induced microglia activation (Fig. 7C), NO generation (Fig. 7B), PI uptake (Fig. 7C), and reduction of dendritic and post-synaptic proteins (Fig. 7D) were substantially ameliorated by co-treatment with either inhibitor. These effects were unlikely to be caused by direct actions of the compounds on neurons because neurons do not express KCa3.1 as discussed above, and doxycycline was shown to provide neuroprotection by regulating microglia but not via neuronal mechanisms (55). Although a direct anti-amyloidogenic property of doxycyline was previously shown (56), our results did not support its direct effect on AβO because we could not demonstrate any effect of doxycycline on the morphology, size, or neurotoxic activities of AβO (data not shown). Therefore, our results indicate that in the more physiological hippocampal slice cultures, low nanomolar AβO causes indirect neurotoxicity by activating microglia.

We also found that human AβO in AD brain extracts induced neurotoxicity in hippocampal slices, which was substantially alleviated by co-treatment with CR, doxycycline, and TRAM-34 (supplemental Fig. S11). This result indicates that, similar to synthetic AβO, AD AβO at low concentrations causes indirect neurotoxicity by activating microglia.

NO Is the Major Mediator of AβO-induced Microglial Neurotoxicity

Because NO is the major inflammatory mediator we have found so far released by AβO-stimulated microglia, we tested whether NO mediates neurotoxicity. We used two selective inhibitors of iNOS, l-NIL (57) and 1400W (58), and found that both compounds significantly blocked the increased NO release induced by AβO (Fig. 8A). When AβO-treated microglia were concurrently treated with iNOS inhibitors, their CM were no longer neurotoxic (Fig. 8B). When applied to cultured hippocampal slices 1 h prior to AβO application, both iNOS inhibitors reduced NO release (Fig. 8C) and inhibited neuronal damage as indicated by reduced PI uptake (Fig. 8D).

DISCUSSION

Our data show that AβO is able to activate microglia at concentrations at least 10-fold lower than those used to induce direct neurotoxicity. Low nanomolar AβO activates microglia to release soluble neurotoxic factors and thus indirectly damages the integrity of neurons and synapses. AβO stimulates a unique neuroinflammatory pattern with increased NO generation but without the production of a regular panel of inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandin E2, glutamate, and the cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. These observations were reproduced using the more physiological hippocampal slices in addition to dissociated microglia cultures. Neurotoxicity was ameliorated by a well studied inhibitor of microglia activation, doxycycline, the KCa3.1 blocker TRAM-34, and two iNOS inhibitors, indicating that KCa3.1 activity and excessive NO release are required for AβO-induced microglial neurotoxicity.

We also found that soluble AβO extracted from AD hippocampi were ∼50 times more potent than synthetic AβO in activating microglia, further suggesting a role of AβO in activating microglia. The reason for the higher potency of brain-derived AβO is not known but is possibly due to the presence of co-fractionated co-stimulators or in vivo modifications of brain-derived Aβ that are not present in synthetic Aβ peptides.

The great majority of prior studies have focused on fAβ because of the observed abundance of activated microglia in and around amyloid plaques (1, 59). However, the ability of fAβ to activate microglia is generally low or absent when fAβ is the only stimulant; activation requires micromolar concentrations (2–100 μm) of fAβ and enhancement by co-stimulators such as γ-interferon, lipopolysaccharides, advanced glycation end products, complement factors, and macrophage colony stimulatory factor (35, 60–65). A few reports showed that unaggregated forms of Aβ at micromolar concentrations were able to activate microglia (14, 65). Tan et al. (66) showed that freshly solubilized, nonaggregated Aβ42 at 500 nm activated microglia in the presence of CD40 ligand. However, it is unlikely that any soluble Aβ42 preparations are devoid of oligomeric Aβ at high nanomolar concentrations. A few groups have investigated the activation of microglia by variably prepared AβO and found that AβO, in concentrations ranging from 2 to 50 μm, was equally or less potent than fAβ in activating microglia (13–17). In contrast to previous studies, we used well defined AβO at concentrations ∼1,000 times lower and were able to show that the potency of AβO was significantly higher than that of fAβ or unaggregatd Aβ in activating microglia. Because this activity has a bell-shaped concentration-response curve, which maximizes at 20–50 nm Aβ, it was not recognized in prior studies using micromolar or high nanomolar Aβ. The reason for the bell-shaped response is not known. Interestingly, a study by Schubert and co-workers (30), conducted prior to our knowledge of Aβ oligomerization, described a similar bell-shaped chemotactic effect of low nanomolar soluble Aβ on microglia/macrophages. In retrospect, their preparation of soluble Aβ, without prior solubilization by hexafluoroisopropanol, likely contained AβO. In contrast, when its effect on neurons was evaluated, AβO showed a nearly linear dose response in causing neuronal death, up to 10 μm (9, 18, 22). The linear dose-response pattern of neuronal AβO potency argues against the possibility that AβO self-aggregates into higher order and therefore less bioactive assemblies when its concentration is above 50 nm.

Soluble nonfibrillar Aβ assemblies have been classified according to their size, structure, and immunological response to conformation-specific antibodies (8). The activities in our AβO preparations and in AD brain lysates reported here can be attributed to the prefibrillar oligomer according to the Glabe classification, because they were immunoneutralized by the conformation-specific antiserum A11 (8). In AD brains, prefibrillar oligomers and other forms of oligomers were found to accumulate focally as clusters of immunoreactive deposits (67–69). It is highly likely that focally AβO can reach the low nanomolar concentrations required for activating microglia in the course of AD development when AβO progressively accumulates (3). In contrast to the relatively permanent nature of plaque-associated inflammation that is prominently detectable histologically, the microglial response to soluble AβO may be transient in nature and resolve after successful Aβ clearance by microglia. Alternatively, AβO-induced focal inflammation may enhance neuronal stress and further increase Aβ deposition, engendering a vicious cycle that is conducive to plaque formation (70, 71). In both scenarios, neurotoxic mediators would be generated to cause indirect neuronal damage and synaptic disruption. This notion of AβO-induced microglia activation is compatible with two recent positron emission tomography studies concluding that stimuli other than plaque fAβ activate microglia in AD patients (4, 5). Notably, within the sensitivity of positron emission tomography detection, Okello et al. (5) were able to detect microglia activation independent of plaque formation in patients with mild cognitive impairment, a prodrome that with a high likelihood precedes AD. The non-fAβ stimuli may thus include AβO. Because levels of soluble Aβ correlate best, whereas numbers of amyloid plaque correlate poorly with the degree of clinical dementia (2, 72, 73), it follows that AβO-activated microglia might play a more significant role than plaque-associated microglia in the cognitive decline of the patient.

AβO was also found concentrated at synaptic sites (74), where it binds postsynaptic density complexes with a high affinity (19, 21, 75). This provides strong evidence for direct AβO toxicity to post-synaptic components, a possible physical basis of synaptic dysfunction in AD. Our results, however, showed that the detrimental effects of AβO upon synapses were ameliorated by inhibitors of microglia activation and therefore support an alternative, microglia-mediated mechanism of synaptic dysfunction. We showed that AβO at low nanomolar concentrations activated microglia and caused reduced levels of critical dendritic and postsynaptic proteins in both dissociated neuronal cultures and hippocampal slices. We also found a pattern of preferential postsysynaptic damage mediated by AβO-activated microglia; this pattern is similar to those found in Tg2576 transgenic mice (76) and in human AD cortex (77), suggesting a pathological relevance. Recently it was found that microglia processes make regular direct contact with synapses and that prolonged contact increases the turnover of synapses (78). Therefore we hypothesize that synaptic AβO might attract microglia by its potent chemotactic effect (30) and promote a synapse-centered neuroinflammatory reaction to damages synapses. Supporting this notion, a previous study showed that the inhibition of NMDA receptor-dependent long term potentiation by soluble Aβ (500 nm, which might contain oligomers) can be prevented by minocycline, a microglia activation inhibitor in the same class as doxycycline, and iNOS inhibition to reduce NO production from microglia (79). Interestingly, NO is the only AβO-promoted mediator we have so far uncovered and mediates AβO-induced microglial neurotoxicity.

One limitation of our experimental paradigm is that although cultures derived from early postnatal brains are currently the standard tool for functional and molecular studies of microglia, the microglia may differ from their adult counterparts in vivo. One alternative approach is to isolate microglia from adult brains without culturing, which may generate microglia samples closer in phenotype to adult microglia in vivo (80, 81). However, this approach has the drawbacks of low yields, limited applications, and potential cell sorting-induced activation. Therefore, based on the current findings, future in vivo experiments such as those utilizing the KCa3.1 knock-out mice and “Aβ oligomer” mice (82) are needed to fully understand the significance of AβO-induced microglia activation in AD.

Microglia are promising cellular targets for controlling harmful CNS inflammation in a wide variety of neurodegenerative disorders (83). The unique mechanism utilized by AβO to activate microglia as well as its potential impact on the development of AD provides an excellent possibility for novel therapeutic approaches. One example we show here is TRAM-34, a small molecule that selectively blocks the intermediate conductance calcium-activated potassium channel KCa3.1 (20, 84, 85). Our data provide the first evidence that a specific K+ channel regulates Aβ-induced microglia activation and neurotoxicity. KCa3.1 regulates Ca2+ signaling by maintaining a negative membrane potential through K+ efflux, thus facilitating Ca2+ entry through a calcium-release activated Ca2+ channel, a channel responsible for the store-operated Ca2+ entry required for microglia activation (44, 86). The anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties of KCa3.1 blockers have been shown in models of traumatic brain injury (87), multiple sclerosis (88), and retinal ganglion cell degeneration after optic nerve transection (44). In addition, TRAM-34, although inhibiting microglia-mediated neurotoxicity, does not affect the beneficial activities of microglia such as migration and phagocytosis (44). Our results suggest that specific KCa3.1 blockers, targeting microglia selectively because of the microglia-restrictive cellular expression of KCa3.1 in the CNS, might provide a novel anti-inflammatory strategy for AD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. George Martin for helpful comments on this manuscript. We thank Dr. Charles Glabe for providing the A11 antibody. We thank colleagues at the University of California Davis Alzheimer's Disease Center for providing frozen brain samples for this study.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants AG025500 and AG031362. This work was also supported by University of California Davis Alzheimer's Disease Center Grant AG010129.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S11.

- Aβ

- amyloid-β protein

- AD

- Alzheimer disease

- fAβ

- amyloid-β fibril

- AβO

- amyloid-β oligomer

- CR

- Congo red

- NFκB

- nuclear factor κB

- SRA

- scavenger receptor A

- iNOS

- inducible NO synthase

- CM

- conditioned medium

- Ac-TN

- acetylated tubulin

- MAP2

- microtubule-associated protein 2

- PSD

- postsynaptic density

- GRIP1

- glutamate receptor-interacting protein 1

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- PI

- [3,8-diamino-5-(3-(diethylmethylamino)propyl)-6-phenyl phenanthridinium diiodide

- l-NIL

- N-iminoethyl-l-lysine

- 1400W

- N-[(3-aminomethyl)benzyl]acetamidine

- BrdUrd

- 5′-bromodeoxyuridine

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cameron B., Landreth G. E. (2010) Neurobiol. Dis. 37, 503–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Terry R. D., Masliah E., Salmon D. P., Butters N., DeTeresa R., Hill R., Hansen L. A., Katzman R. (1991) Ann. Neurol. 30, 572–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hardy J., Selkoe D. J. (2002) Science 297, 353–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Edison P., Archer H. A., Gerhard A., Hinz R., Pavese N., Turkheimer F. E., Hammers A., Tai Y. F., Fox N., Kennedy A., Rossor M., Brooks D. J. (2008) Neurobiol. Dis. 32, 412–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Okello A., Edison P., Archer H. A., Turkheimer F. E., Kennedy J., Bullock R., Walker Z., Kennedy A., Fox N., Rossor M., Brooks D. J. (2009) Neurology 72, 56–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Caughey B., Lansbury P. T. (2003) Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 26, 267–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Necula M., Kayed R., Milton S., Glabe C. G. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 10311–10324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Glabe C. G. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29639–29643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lambert M. P., Barlow A. K., Chromy B. A., Edwards C., Freed R., Liosatos M., Morgan T. E., Rozovsky I., Trommer B., Viola K. L., Wals P., Zhang C., Finch C. E., Krafft G. A., Klein W. L. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 6448–6453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lesné S., Koh M. T., Kotilinek L., Kayed R., Glabe C. G., Yang A., Gallagher M., Ashe K. H. (2006) Nature 440, 352–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shankar G. M., Li S., Mehta T. H., Garcia-Munoz A., Shepardson N. E., Smith I., Brett F. M., Farrell M. A., Rowan M. J., Lemere C. A., Regan C. M., Walsh D. M., Sabatini B. L., Selkoe D. J. (2008) Nat. Med. 14, 837–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Roychaudhuri R., Yang M., Hoshi M. M., Teplow D. B. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 4749–4753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Takata K., Kitamura Y., Umeki M., Tsuchiya D., Kakimura J., Taniguchi T., Gebicke-Haerter P. J., Shimohama S. (2003) J. Pharmacol. Sci. 91, 330–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hashioka S., Monji A., Ueda T., Kanba S., Nakanishi H. (2005) Neurochem. Int. 47, 369–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jimenez S., Baglietto-Vargas D., Caballero C., Moreno-Gonzalez I., Torres M., Sanchez-Varo R., Ruano D., Vizuete M., Gutierrez A., Vitorica J. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28, 11650–11661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sondag C. M., Dhawan G., Combs C. K. (2009) J. Neuroinflamm. 6, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Parvathy S., Rajadas J., Ryan H., Vaziri S., Anderson L., Murphy G. M., Jr. (2009) Neurobiol. Aging 30, 1792–1804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dahlgren K. N., Manelli A. M., Stine W. B., Jr., Baker L. K., Krafft G. A., LaDu M. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32046–32053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lacor P. N., Buniel M. C., Chang L., Fernandez S. J., Gong Y., Viola K. L., Lambert M. P., Velasco P. T., Bigio E. H., Finch C. E., Krafft G. A., Klein W. L. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24, 10191–10200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wulff H., Miller M. J., Hansel W., Grissmer S., Cahalan M. D., Chandy K. G. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 8151–8156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maezawa I., Hong H. S., Liu R., Wu C. Y., Cheng R. H., Kung M. P., Kung H. F., Lam K. S., Oddo S., Laferla F. M., Jin L. W. (2008) J. Neurochem. 104, 457–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maezawa I., Hong H. S., Wu H. C., Battina S. K., Rana S., Iwamoto T., Radke G. A., Pettersson E., Martin G. M., Hua D. H., Jin L. W. (2006) J. Neurochem. 98, 57–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hong H. S., Maezawa I., Yao N., Xu B., Diaz-Avalos R., Rana S., Hua D. H., Cheng R. H., Lam K. S., Jin L. W. (2007) Brain Res. 1130, 223–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gong Y., Chang L., Viola K. L., Lacor P. N., Lambert M. P., Finch C. E., Krafft G. A., Klein W. L. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 10417–10422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kayed R., Head E., Thompson J. L., McIntire T. M., Milton S. C., Cotman C. W., Glabe C. G. (2003) Science 300, 486–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maezawa I., Nivison M., Montine K. S., Maeda N., Montine T. J. (2006) FASEB J. 20, 797–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xiang H., Kinoshita Y., Knudson C. M., Korsmeyer S. J., Schwartzkroin P. A., Morrison R. S. (1998) J. Neurosci. 18, 1363–1373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bernardino L., Xapelli S., Silva A. P., Jakobsen B., Poulsen F. R., Oliveira C. R., Vezzani A., Malva J. O., Zimmer J. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25, 6734–6744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Franciosi S., Ryu J. K., Choi H. B., Radov L., Kim S. U., McLarnon J. G. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26, 11652–11664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Davis J. B., McMurray H. F., Schubert D. (1992) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 189, 1096–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kuo Y. M., Emmerling M. R., Vigo-Pelfrey C., Kasunic T. C., Kirkpatrick J. B., Murdoch G. H., Ball M. J., Roher A. E. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 4077–4081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stenh C., Englund H., Lord A., Johansson A. S., Almeida C. G., Gellerfors P., Greengard P., Gouras G. K., Lannfelt L., Nilsson L. N. (2005) Ann. Neurol. 58, 147–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shie F. S., Jin L. W., Cook D. G., Leverenz J. B., LeBoeuf R. C. (2002) Neuroreport 13, 455–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bornemann K. D., Wiederhold K. H., Pauli C., Ermini F., Stalder M., Schnell L., Sommer B., Jucker M., Staufenbiel M. (2001) Am. J. Pathol. 158, 63–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Xie Z., Wei M., Morgan T. E., Fabrizio P., Han D., Finch C. E., Longo V. D. (2002) J. Neurosci. 22, 3484–3492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maezawa I., Maeda N., Montine T. J., Montine K. S. (2006) J. Neuroinflamm. 3, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. El Khoury J., Hickman S. E., Thomas C. A., Cao L., Silverstein S. C., Loike J. D. (1996) Nature 382, 716–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Paresce D. M., Ghosh R. N., Maxfield F. R. (1996) Neuron 17, 553–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yrjänheikki J., Keinänen R., Pellikka M., Hökfelt T., Koistinaho J. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 15769–15774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jantzie L. L., Cheung P. Y., Todd K. G. (2005) J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 25, 314–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bernardino A. L., Kaushal D., Philipp M. T. (2009) J. Infect. Dis. 199, 1379–1388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gallin E. K. (1984) Biophys. J. 46, 821–825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Khanna R., Roy L., Zhu X., Schlichter L. C. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol 280, C796–C806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kaushal V., Koeberle P. D., Wang Y., Schlichter L. C. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27, 234–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ghanshani S., Wulff H., Miller M. J., Rohm H., Neben A., Gutman G. A., Cahalan M. D., Chandy K. G. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 37137–37149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Eder C., Fischer H. G., Hadding U., Heinemann U. (1995) J. Membr. Biol. 147, 137–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schilling T., Eder C. (2003) Pflugers Arch. 447, 312–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schilling T., Stock C., Schwab A., Eder C. (2004) Eur. J. Neurosci. 19, 1469–1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kettenmann H., Hoppe D., Gottmann K., Banati R., Kreutzberg G. (1990) J Neurosci. Res. 26, 278–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Takeuchi H., Jin S., Wang J., Zhang G., Kawanokuchi J., Kuno R., Sonobe Y., Mizuno T., Suzumura A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 21362–21368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hoogenraad C. C., Milstein A. D., Ethell I. M., Henkemeyer M., Sheng M. (2005) Nat. Neurosci. 8, 906–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Joiner W. J., Wang L. Y., Tang M. D., Kaczmarek L. K. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 11013–11018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ishii T. M., Silvia C., Hirschberg B., Bond C. T., Adelman J. P., Maylie J. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 11651–11656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vornov J. J., Tasker R. C., Coyle J. T. (1991) Exp. Neurol. 114, 11–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lai A. Y., Todd K. G. (2006) Glia 53, 809–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Forloni G., Colombo L., Girola L., Tagliavini F., Salmona M. (2001) FEBS Lett. 487, 404–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Connor J. R., Manning P. T., Settle S. L., Moore W. M., Jerome G. M., Webber R. K., Tjoeng F. S., Currie M. G. (1995) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 273, 15–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Li J., Baud O., Vartanian T., Volpe J. J., Rosenberg P. A. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 9936–9941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bamberger M. E., Harris M. E., McDonald D. R., Husemann J., Landreth G. E. (2003) J Neurosci. 23, 2665–2674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Meda L., Cassatella M. A., Szendrei G. I., Otvos L., Jr., Baron P., Villalba M., Ferrari D., Rossi F. (1995) Nature 374, 647–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Muehlhauser F., Liebl U., Kuehl S., Walter S., Bertsch T., Fassbender K. (2001) Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 39, 313–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Veerhuis R., Van Breemen M. J., Hoozemans J. M., Morbin M., Ouladhadj J., Tagliavini F., Eikelenboom P. (2003) Acta Neuropathol. 105, 135–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gasic-Milenkovic J., Dukic-Stefanovic S., Deuther-Conrad W., Gärtner U., Münch G. (2003) Eur. J. Neurosci. 17, 813–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Li M., Pisalyaput K., Galvan M., Tenner A. J. (2004) J. Neurochem. 91, 623–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lindberg C., Selenica M. L., Westlind-Danielsson A., Schultzberg M. (2005) J Mol. Neurosci. 27, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tan J., Town T., Paris D., Mori T., Suo Z., Crawford F., Mattson M. P., Flavell R. A., Mullan M. (1999) Science 286, 2352–2355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kokubo H., Kayed R., Glabe C. G., Yamaguchi H. (2005) Brain Res. 1031, 222–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lambert M. P., Velasco P. T., Chang L., Viola K. L., Fernandez S., Lacor P. N., Khuon D., Gong Y., Bigio E. H., Shaw P., De Felice F. G., Krafft G. A., Klein W. L. (2007) J. Neurochem. 100, 23–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. van Helmond Z., Miners J. S., Kehoe P. G., Love S. (2010) Brain Pathol. 20, 468–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Bahr B. A., Hoffman K. B., Yang A. J., Hess U. S., Glabe C. G., Lynch G. (1998) J. Comp. Neurol. 397, 139–147 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Tamagno E., Guglielmotto M., Aragno M., Borghi R., Autelli R., Giliberto L., Muraca G., Danni O., Zhu X., Smith M. A., Perry G., Jo D. G., Mattson M. P., Tabaton M. (2008) J. Neurochem. 104, 683–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lue L. F., Kuo Y. M., Roher A. E., Brachova L., Shen Y., Sue L., Beach T., Kurth J. H., Rydel R. E., Rogers J. (1999) Am. J. Pathol. 155, 853–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. McLean C. A., Cherny R. A., Fraser F. W., Fuller S. J., Smith M. J., Beyreuther K., Bush A. I., Masters C. L. (1999) Ann. Neurol. 46, 860–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Deshpande A., Kawai H., Metherate R., Glabe C. G., Busciglio J. (2009) J. Neurosci. 29, 4004–4015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Lacor P. N., Buniel M. C., Furlow P. W., Clemente A. S., Velasco P. T., Wood M., Viola K. L., Klein W. L. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27, 796–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Calon F., Lim G. P., Yang F., Morihara T., Teter B., Ubeda O., Rostaing P., Triller A., Salem N., Jr., Ashe K. H., Frautschy S. A., Cole G. M. (2004) Neuron 43, 633–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Gylys K. H., Fein J. A., Yang F., Wiley D. J., Miller C. A., Cole G. M. (2004) Am. J. Pathol. 165, 1809–1817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wake H., Moorhouse A. J., Jinno S., Kohsaka S., Nabekura J. (2009) J. Neurosci. 29, 3974–3980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Wang Q., Rowan M. J., Anwyl R. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24, 6049–6056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Carson M. J., Reilly C. R., Sutcliffe J. G., Lo D. (1998) Glia 22, 72–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hickman S. E., Allison E. K., El Khoury J. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28, 8354–8360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Tomiyama T., Matsuyama S., Iso H., Umeda T., Takuma H., Ohnishi K., Ishibashi K., Teraoka R., Sakama N., Yamashita T., Nishitsuji K., Ito K., Shimada H., Lambert M. P., Klein W. L., Mori H. (2010) J. Neurosci. 30, 4845–4856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. McGeer E. G., McGeer P. L. (2010) J. Alzheimers Dis. 19, 355–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Wulff H., Kolski-Andreaco A., Sankaranarayanan A., Sabatier J. M., Shakkottai V. (2007) Curr. Med. Chem. 14, 1437–1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Wulff H., Zhorov B. S. (2008) Chem. Rev. 108, 1744–1773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Ohana L., Newell E. W., Stanley E. F., Schlichter L. C. (2009) Channels 3, 129–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Mauler F., Hinz V., Horváth E., Schuhmacher J., Hofmann H. A., Wirtz S., Hahn M. G., Urbahns K. (2004) Eur. J. Neurosci. 20, 1761–1768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Reich E. P., Cui L., Yang L., Pugliese-Sivo C., Golovko A., Petro M., Vassileva G., Chu I., Nomeir A. A., Zhang L. K., Liang X., Kozlowski J. A., Narula S. K., Zavodny P. J., Chou C. C. (2005) Eur. J. Immunol. 35, 1027–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.