Abstract

Interfering intracellular antibodies are valuable for biological studies as drug surrogates and as potential macromolecular drugs per se. Their application is still limited because of the difficulty of acquisition of functional intracellular antibodies. We describe the use of the new intracellular antibody capture procedure (IAC3) to facilitate direct isolation of functional single domain antibody fragments using four independent target molecules (LMO2, TP53, CRAF1, and Hoxa9) from a set of diverse libraries. Initially, these have variability in only one of the three antigen-binding CDR regions of VH or VL and first round single domains are affinity matured by iterative randomization of the two other CDRs and reselection. We highlight the approach using a single domain binding to LMO2 protein. Our results show that interfering with LMO2 protein function demonstrates a role specifically in erythroid differentiation, confirm a necessary and sufficient function for LMO2 as a cancer therapy target in T-cell neoplasia and allowed for the first time production of soluble recombinant LMO2 protein by co-expression with intracellular domain antibodies. Co-crystallization of LMO2 and the anti-LMO2 VH protein was successful. These results demonstrate that this third generation IAC3 offers a robust toolbox for various biomedical applications and consolidates functional features of the LMO2 protein complex, which includes the importance of Lmo2-Ldb1 protein interaction.

Keywords: Antibodies, Cancer Therapy, Erythropoeisis, Hematopoiesis, Homeobox, Immunology, Leukemia, Protein Drug Interactions, Protein Structure, Protein-Protein Interactions

Introduction

Antibodies and derivative fragments are molecules that can capture a huge variety of antigens with high specificity and affinity and are indispensable tools and reagents in bioscience and in medicine (1). The utilities of intracellular application of antibody fragments is that, unlike gene knock-out and interfering RNAs or antisense, these molecules interfere with cellular functions directly by binding to target proteins and can therefore target specific properties of proteins such as particular signal transduction via blockading protein-protein interaction (2, 3). This not only provides valuable and robust tools in biological analysis such as functional genomics and proteomics but also serve as drug surrogates to establish the target validity for drug development by ascertaining the biological effects from targeting the protein. To make these options possible on a broad basis, robust screening methods with high quality libraries are needed to allow selection of target-specific intracellular antibodies.

Antibody binding sites comprise heavy chain variable domain (VH)4 and light chain variable domains (VL), each with three complementarity determining regions (CDRs), directly contacting antigen and concerned in binding affinity and specificity. Single domain antibody fragments (DAbs), comprising either VH or VL, encompass a minimal antigen recognition can also be used for intracellular applications, so-called intracellular domain antibodies (iDAbs) (4). Structural analysis of V regions based on a consensus framework sequence have shown that essentially no difference exists between VH or VL with or without disulfide bonds (5), and these can be used as intracellular functional agents (4, 6).In addition, this property allows libraries of iDAbs to be developed based on the single consensus framework sequence but diverse CDR sequences (4). The single domain comprising specific V region framework scaffolds have excellent properties of solubility, stability, and high expression levels within the cell (7).

The latest generation of intracellular antibody capture (IAC3 (8)) allows for screening without the need for preparation of native antigen in vitro (as in IAC (4, 9, 10)) and overcomes the hitherto restricted V region diversity inherent to yeast methods, by employing a series of single domain VH and VL libraries, each with amino acid randomization initially only at the CDR3. Here, we describe use of IAC3 to isolate VH or VL iDAbs binding to LMO2, TP53, CRAF1, and Hoxa9. We have characterized one VH binding to LMO2 in cells that can inhibit the Lmo2 protein-protein interactions in cells and interfere with Lmo2 function in an erythroid differentiation and in a T-cell tumorigenesis assay. Furthermore, because the anti-LMO2 VH was selected against native LMO2 protein, co-expressing the VH with LMO2 in Escherichia coli facilitated bulk production of soluble recombinant LMO2 protein and crystallization of the protein complex for the first time. These results illustrate that the iDAbs isolated from the libraries by IAC3 can be applied successfully to difficult problems in biochemical and structural analysis in addition to dissecting in vivo cell biology.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bait Plasmids

pBTM116-LMO2 (codons 26–159, see supplemental Fig. S3) is described elsewhere (11). pBD-LMO2 was constructed by subcloning the EcoRI and PstI fragment from pBTM116-LMO2 into EcoRI/PstI sites of pBD-Gal4-Cam (Stratagene).

pBTM116-Hoxa9HD and pBD-Hoxa9HD were constructed by subcloning the fragment of mouse homeobox-a9 homeodomain (Hoxa9-HD, codons 205–267), from cDNA prepared from mouse spleen RNA into the EcoRI/PstI sites of the parental vectors. pBTM116-CRAF1-RBD and pBD-CRAF1-RBD were constructed by subcloning the cDNA fragment of human CRAF1 RAS binding domain (CRAF1-RBD, codon 1 to 151) into the EcoRI/BamHI sites of the parental vectors. pBTM116-TP53 and pBD-TP53 were constructed by subcloning the fragment of human TP53 cDNA with R273H mutation (codon 73 to 393) into the EcoRI/BamHI sites of the parental vectors.

iDAb Library Construction and IAC Screening

The principle method to construct single domain VH or VL libraries in the yeast prey expression vector pVP16* (which carries the leucine auxotrophy gene) is shown in supplemental Fig. S1 and described in detail elsewhere (12). pEFVP16-VH#6 (13) was used as the parental template for the VH libraries, and pEFVP16-VL#204 (14) was used for the single VL library. Fragments containing single domains with unchanged CDR1 and CDR2 and randomized CDR3 were amplified by PCR with EFFP5 and one of 14 rdmVHCDR3Rev-n primers designed to both randomize and vary the length of CDR3 (for VH) or EFFP5 and rdmVLCDR3Rev (for VL) (primer sequences in supplemental Fig. S1E). Amplified PCR fragments were purified from 2% agarose gel and purified, and further PCRs were performed with EFFP5 and NXJH5R2 (for VH) or VLDR2 (for VL) to cloning into pVP16* cut with SfiI and NotI to generate the 14 VH libraries (each with a different length of CDR3) and one VL library. The initial diversity of each library is shown in supplemental Fig. S2 (estimated from total transformants and the ratio of in-frame fusion of VH or VL with the VP16 segment). Amplification of the library was done by plating primary transformants on 25 × 25 cm LB plates containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin (at maximum of 2–4 × 105 colonies/plate) and incubating at 37 °C overnight. All the colonies were harvested by scraping, and plasmid DNAs were extracted by alkaline lysis method and further purified by using caesium chloride ultracentrifugation. IAC screening of single domain VH and VL libraries was performed in accordance with the protocol of the third generation IAC screening method as described elsewhere in detail (8).

Mammalian Two-hybrid (M2H) Assays

Transient mammalian two-hybrid assays (15) have been described elsewhere (4). Antibody fragments cloned into the SfiI and NotI sites of the pEFVP16 mammalian prey vector (12) were anti-LMO2 VH#576 and VL#551 (isolated from yeast IAC3 single domain library screening), anti-LMO2 scFv ALR3 (11), anti-ATF2 VH#27 (4), or anti-RAS VH#6 (13). Bait clones expressing Gal4-DBD-antigen fusions were cloned in pM (16), and the various forms of LMO2 bait and Gal4-DBD-RAS have been described previously (4, 11). For transient transfection, pM bait, pEFVP16-prey, pG5-Fluc, and pRL-CML plasmids were co-transfected into CHO cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). At 48 h after transfection, the cells were lysed and assayed with the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Competitive M2H Assays

We have established a “one-plasmid” mammalian two-hybrid assay system for competitive M2H assays using a Triplex vector (8), which allows expression of a prey protein-VP16 fusion (from the EF1α promoter) and a bicistronic mRNA (from the SV40 early promoter) comprising the Gal4-DBD-bait fusion-internal ribosome entry site-Renilla luciferase. Transfection of this plasmid was carried out into a line of CHO cells stably carrying a Firefly luciferase gene with Gal4 DNA binding sites (CHOluc15 (8)).

Anti-LMO2 VH#576 or VL#551 were subcloned into SfiI and NotI sites of the Triplex vector to produce an iDAb-VP16 fusion gene, and LMO2 was subcloned into the BamHI/PstI sites to produce a Gal4DBD-LMO2 fusion gene. As competitors, scFv or single domains were subcloned into pEF/Myc/nuc (Invitrogen). For competitive M2H assays, the CHOluc15 were seeded in 12-well culture plates the day before transfection and grown until >90% confluent. One μg triplex vector and 1 or 2 μg competitor plasmid was transfected using 2 μl Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 48 h, the cells were harvested, lysed, and assayed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The data represent a minimum of three experiments for each point, and each of which was performed in duplicate. Values are normalized for stimulated Firefly luciferase levels compared with levels for transfected Renilla luciferase.

Erythroid Differentiation Assay in MEL Cells

To determine the biological effects of the IAC-selected anti-LMO2 iDAb VH#576 in vivo, hexamethylene bisacetamide (HMBA) induced erythroid differentiation assays were performed with amurine erythroleukemia (MEL) cells expressing various single domains. MEL cell clone 585 (a kind gift from professor D. R. Higgs) were grown in suspension culture in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% fetal calf serum plus penicillin and streptomycin. To express single domains in MEL cells, retroviruses encoding VH or VL were constructed by subcloning the single domain PCR fragments with nuclear localization signal into the BglII/EcoRI sites of pMIG (17) and were transiently transfected into Plat-E viral packaging cells (18) using Lipofectamine 2000. Two days after transfection, culture medium containing retrovirus were harvested and used to infect MEL585 by spinoculation at 650 × g for 1.5 h at 25 °C. Forty-eight hours after infection, GFP-positive MEL cells were separated by sorting using a Cytomation MOFLOW flow cytometer. One million GFP-positive cells were seeded into 6-cm culture dishes and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% fetal calf serum plus penicillin and streptomycin with or without 4 mm HMBA. After initiation of HMBA treatment, an aliquot of the culture was harvested for cell number counting, hemoglobin staining, and Western blotting. The viable cell numbers were calculated by adding 20 μl cell culture to 20 μl trypan blue (0.4%, w/v), and viability was assessed based on the exclusion of the dye by live cells. Cell counts were conducted in triplicate. To test hemoglobin production in MEL cells, the cells were stained with diaminofluorene (DAF). A DAF stock solution was prepared to a final concentration of 10 mg/ml DAF (Sigma) in 90% glacial acetic acid and stored at 4 °C. The staining solution was prepared by adding 50 μl of DAF stock and 30 μl of 30% H2O2 to 500 μl of 0.2 m Tris-HCl, pH 7.0. 50 μl cell suspension in PBS were added to 50 μl of DAF staining solution and left at room temperature for 2 min, and the blue staining cells were counted under the microscope. To detect protein expression in the cells, the harvested cells were lysed by resuspending in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 1% Nonidet P-40, 150 mm NaCl, 1% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS) and incubated on ice for 30 min. After spinning, the supernatants were fractionated by 15% SDS-PAGE gel, transferred to PVDF membranes, and were immunodetected with anti-LMO2 monoclonal antibody (19) and anti-α-tubulin monoclonal antibody (B-5-1-2, Sigma) as the SDS-PAGE loading control.

Nude Mouse Transplantation Assay

A transgenic line has been established in which Lmo2 is expressed under the control of the T-cell promoter Lck and transplantable T-cell neoplasias arise in these mice, manifest by thymoma and splenomegaly.5 T-cells from Lck-Lmo2 thymoma were injected into CD1 nude (nu/nu) mouse recipients and splenomegaly allowed to occur. Immediately after sacrifice and harvesting the splenic neoplastic T-cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium with 20% FCS, 200 μg/ml gentamycin (Sigma), 20 units/ml recombinant murine IL-2, 10 units/ml recombinant murine IL-6, and 10 units/ml recombinant human IL-7 plus penicillin and streptomycin for 48 h, and these dividing cell populations were infected with pMIG-derived retroviruses as described above. The pMIG vector allows expression of an iDAb and co-expression of GFP, allowing determination of the proportion of infected cells by flow cytometry. Specific iDAb-expressing viruses were made expressing anti-LMO2 VH#576 with a nuclear localization signal (pMIG-VH#576-nuc) or anti-RAS VH#6 with nuclear localization signal (pMIG-VH#6-nuc) and GFP.

Following flow cytometric determination of percentage of infected cells, the infected populations were used for transplantation in CD1 nu/nu mice. A bolus of one million T-cells containing the infected GFP-expressed population was injected into the tail vein of recipient CD1 nu/nu mice, and recipient mice were sacrificed at 4–6 weeks (when the mice showed lymph node enlargement in mandibular, axillary, and iliac regions) after injection by which time splenomegaly was observed. The spleens were dissected from mice and weighed. To prepare single T-cell suspensions for flow cytometry, the spleen was minced in cold PBS, passed through a cell strainer (70 μm of nylon), treated with red blood cell lysis buffer (150 mm NH4Cl, 10 mm KHCO3, and 0.1 mm EDTA) for 2 min at room temperature, and single cells were finally resuspended in PBS with 1% FCS. The percentage of GFP expressed cells in spleen was assessed by flow cytometry and compared with the initial population before transplantation.

Protein Expression and Purification

For co-expression of recombinant LMO2 and the anti-LMO2 VH single domain, isolated from IAC, bicistronic expression vectors were constructed by subcloning anti-LMO2 VH#576 and various truncated forms of LMO2 cDNA in pRK-HISTEV (13) and transformed into the C41(DE3) bacterial strain (20). The transformed bacteria were grown in LB with 100 μg/ml ampicillin at 37 °C until A600 nm 0.6 at which stage ZnSO4 was added to a final concentration of 0.1 mm. Protein expression was induced by addition of isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (final concentration, 0.5 mm) at 16 °C overnight (up to 16 h). The cell pellet was resuspended in 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 250 mm NaCl, 20 mm imidazole, 1 μm ZnSO4, and 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol. Proteins were extracted by cell disruption (Constant Systems Ltd., UK) at 25,000 psi. LMO2 and anti-LMO2 VH single domain were co-purified using a Ni2+-charged HiTrap chelating HP column (5 ml, GE healthcare) using a gradient elution from 20 to 300 mm imidazole. The protein purity was analyzed by SDS-PAGE stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. The appropriate fractions were pooled and completely digested with His-tagged tobacco etch virus protease during dialysis against the buffer without imidazole at 4 °C overnight. The protein complex was repurified with nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (Qiagen) to remove cleaved His6 tags and tobacco etch virus protease. The unbound fractions (LMO2-anti LMO2 VH#576) were concentrated using an Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter device with Ultracel-10 membrane (Millipore) and were further purified by gel filtration with HiLoad Superdex-75 (GE Healthcare) in 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 150 mm NaCl, and 1 mm DTT. Fractions corresponding to the LMO2-anti-LMO2 VH#576 complex were pooled and concentrated again to ∼10 mg/ml for further experiments.

Circular Dichroism Measurement

Far-UV CD spectra were recorded on the Jasco J-715 spectropolarimeter (Jasco Spectroscopic Co., Ltd.) equipped with a Peltier temperature control unit. CD data were collected by scanning in the wavelength range of 190–260 nm with a resolution of 1 nm and a response time of 8 s. Final spectra were the sum of 10 scans accumulated at a scanning speed of 50 nm/min. Background contribution due to buffer was subtracted. The concentration of the sample was 0.22 mg/ml and dissolved in 25 mm NaH2PO4, pH 8.

Crystallization of LMO2-anti-LMO2 Single Domain Complex

Crystallization conditions were screened at 294 K by the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method using Greiner 96 well crystallization plates (Greiner Bio-One Ltd). The Cartesian Technologies MicroSys MIS4000 pipetting instrument (Digilab Genomic Solutions) was used to perform nanoliter-scale crystallization experiments. Reservoir solutions were taken from commercial crystallization screening kits (Hampton Research): Crystal Screen I, Crystal Screen II, Salt RX, Index, Natrix, Grid Screen PEG 6000, Grid screen ammonium sulfate, Grid screen PEG/LiCl, Grid screen NaCl, Grid screen MPD, and “Quik screen” sodium phosphate. 96 solutions from each screen were dispensed, in 95-μl volumes, into the crystallization plate reservoirs by a Robbins Hydra-96 microdispenser (Art Robbins Instruments). These plates were processed by the Cartesian robot, which first dispensed 100-nl protein droplets onto the 96 crystallization platforms and then added 100 nl from the reservoir solution to each platform. The plates were sealed manually using transparent self-adhesive foil (Greiner). Crystals formed in 2 days at 294 K using Natrix reagent N5 (0.2 m potassium chloride, 0.01 m magnesium chloride hexahydrate, 0.05 m MES monohydrate, pH 5.6, 5% w/v polyethylene glycol 8000), Natrix reagent N3 (0.1 m magnesium acetate tetrahydrate, 0.05 m MES monohydrate, pH 5.6, 20% (v/v) (±)-2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol), and Grid screen ammonium sulfate A3 100 mm MES monohydrate, pH 6.0, 0.8 m ammonium sulfate. The protein crystals were confirmed as containing both LMO2 and VH#576 by SDS-PAGE using silver staining (supplemental Fig. S4C).

RESULTS

Selection of Antigen-specific iDAbs Using IAC3

To maximize the possibility of isolating iDAbs against any antigen using IAC3, a series of single domain VH or VL synthetic libraries with different length of CDR3 have been designed and constructed (supplemental Fig. S1, A–D). The randomisation of codons in CDR3 was achieved by PCR mutagenesis method with oligonucleotide primers shown in supplemental Fig. S1E (12). The single domain anti-RAS VH#6 and VL#204 were used as the templates for PCR reactions. For VH libraries, 14 VH single domain libraries with different length of CDR3 (from 8 to 21 residues, according to ImMunoGeneTics information system numbering (21), supplemental Fig. S2) were prepared. A single VL library was prepared because the VL CDR3 is invariant in length. The diversity of each library is shown on supplemental Fig. S2 together with the percentage of clones with open reading frames determined by sequence analysis of 10–20 randomly selected clones from each library.

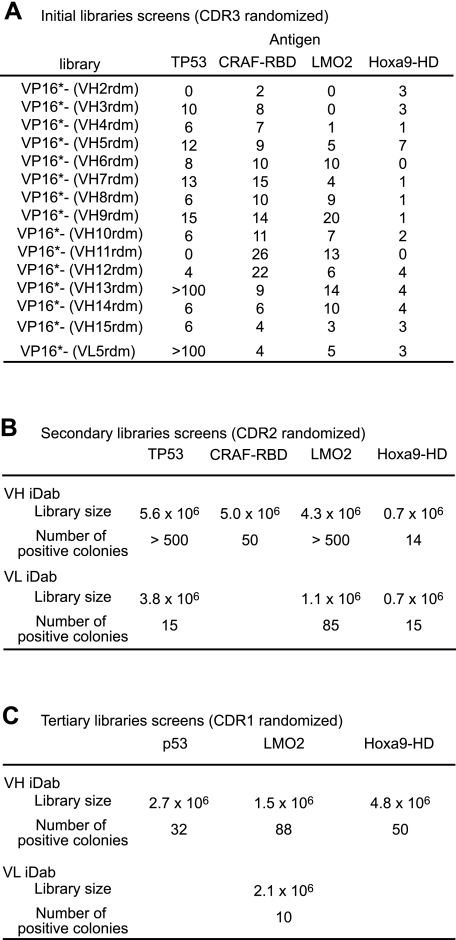

The utility of these IAC3 libraries as sources of intracellular antibodies was assessed using a panel of different intracellular protein antigens, namely LMO2, TP53, CRAF1-RBD, and Hoxa9-HD. The bait plasmids for each protein, constructed by fusion to the DNA-binding domains of LexA (in pBTM116) or Gal4 (in pBD-Gal4). Initial rounds of screening of single domain libraries with CDR3 randomization were performed with LexA-antigen fusions (Fig. 1A) and interaction of bait (LexA-antigen) and prey (iDAb) confirmed with lacZ reporter expression. Prey plasmid DNAs were rescued from each initial screen, pooled, and used as PCR templates for constructing second sublibraries with CDR2 randomized. (The size of the sublibraries for each antigen are shown in Fig. 1B.) Positives from screening these secondary libraries were again pooled, and finally the CDR1 was randomized (Fig. 1C) for a tertiary screen. The Gal4-DBD antigen fusion was used as the bait in secondary and tertiary screens, to avoid carrying through VH or VL that bind to either the LexA-DBD or the DBD-antigen fusion region from initial screening.

FIGURE 1.

Single domain VH and VL library screening data. The 15 libraries (14 VH and 1 VL library) were screened with four different antigen baits (TP53, CRAF1-RBD, LMO2, and Hoxa9-HD). Initial screens used the bait vector pBTM116 vector encoding LexA-DBD-fusion, the indicated numbers of yeast clones growing on −WLH selection plates anti-LMO2 and Hoxa9-HD screens were carried out in the presence of 8 mm 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole. B, for the secondary library screens, all clones that grew on −WLH selection plates and were positive on X-gal staining on initial screening were pooled, the CDR2 regions were randomized, and a new sublibrary was screened using pBD-cam bait vectors. The results show the number of colonies growing on −WLH plates with 50 mm (or 100 mm 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole for the VL screened with Gal4-DBD-LMO2). C, a tertiary library screen was carried out with the LMO2, TP53, and Hoxa9-HD baits using new sublibraries made by randomization of CDR1 from pooled secondary screen clones. The sizes of sublibraries are shown with the number of clones growing on −WLH plates with 75 mm (for Hoxa9-HD), 150 mm (for TP53), or 200 mm 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (for LMO2).

On secondary screening, large numbers of colonies from VH sublibraries grew on tryptophan, leucine, and histidine dropout selection plates. To restrict the iDAbs to those with the highest specificity and affinity, we repeated screening of LMO2, TP53, and Hoxa9-HD sublibraries with randomized CDR1 under stringent conditions of 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole concentration. Finally, we obtained 88 anti-LMO2, 32 anti-TP53, and 50 anti-Hoxa9-HD VH segments and 10 anti-LMO2 VL segments (Fig. 1C). The amino acid sequences of representative anti-LMO2, anti-TP53, and anti-Hoxa9 single domains are shown in Fig. 2.

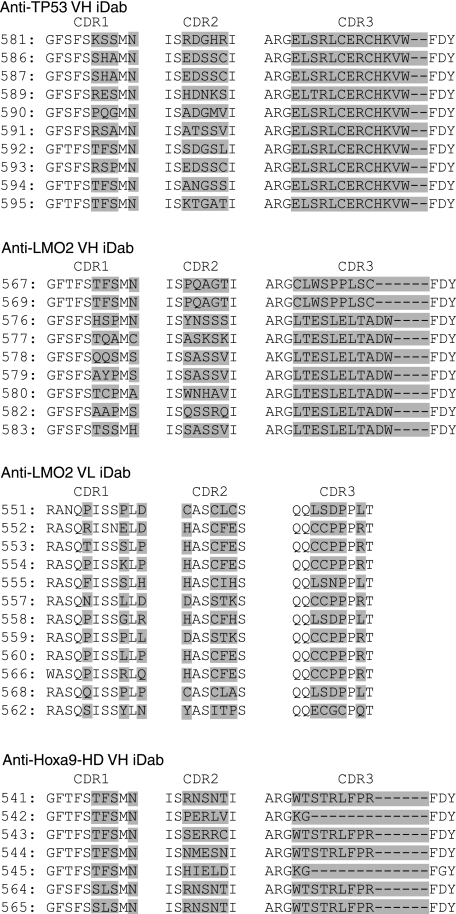

FIGURE 2.

VH or VL amino acid sequences of selected single domains. The amino acid (single letter code) of iDAbs isolated from the tertiary library screens with TP53, LMO2, and Hoxa9-HD baits. In these sequences, residues that were randomized in the libraries are highlighted for each CDR. The iDAbs shown are selected from a variety of screens and those for TP53 are all from the VH library with 19-residue CDR3 (VH13rdm, Fig. 1); those for LMO2 were from either VH libraries VH9rdm or 11rdm) or the VL library; and those for Hoxa9HD were from either VH2rdm or VH9rdm).

Production and Crystallization of Recombinant LMO2 in Complex with a Single VH Domain

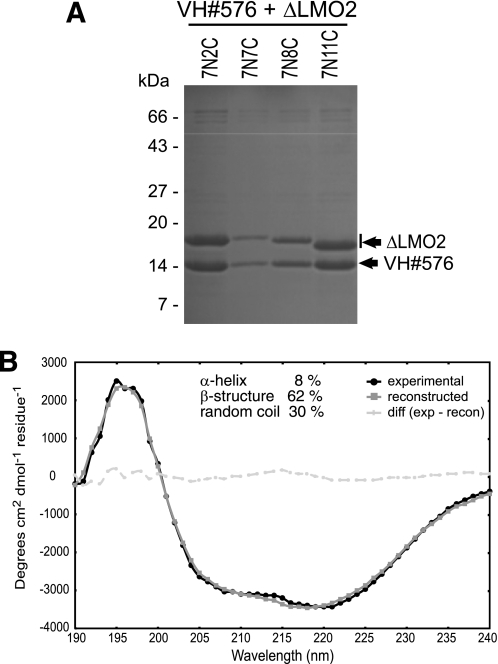

Although protein expression in E. coli offers a rapid way of producing bulk recombinant protein, often target proteins (including LMO2, where our previous attempts at recombinant LMO2 expression had only resulted in LMO2 inclusion bodies in all tested experimental conditions) prove problematic to express as soluble and correctly folded proteins in quantities sufficient for structure determination, e.g. crystallization or NMR spectroscopy. IAC methods develop single domains that are selected using native protein antigens (i.e. because the selection works in vivo) and thus to evaluate the utility of these single domains as tools for biophysical analysis, we assessed synthesis of soluble recombinant LMO2 protein via co-expression with the VH#576 single domain. A His-tagged VH#576 and various forms of LMO2, encoding short truncations of LMO2 at N- and C-terminal ends, were cloned into a bicistronic expression vector, expressed in bacteria at 16 °C and co-purified with nickel-affinity chromatography. The purified complexes were analyzed by SDS-PAGE showing excellent levels of expression for all the LMO2 forms with approximately stoichiometric amounts of VH (Fig. 3A). The best yields were obtained with LMO2-Δ7N11C (LMO2 truncated seven amino acids of N-terminal and 11 of C-terminal regions, see supplemental Fig. S3) and VH#576, and the amounts were >10 mg per liter of bacterial culture. The quality of the LMO2 and VH#576 proteins was assessed by estimating the proportion of secondary structure using far-UV CD spectra (Fig. 3B). Spectra showed the complex contains significant levels of secondary structure, estimating 8% α-helix, 62% β-structure, and 30% random coil.

FIGURE 3.

Production of soluble recombinant LMO2 by co-expression with anti-LMO2 VH#576. Recombinant LMO2 was produced by co-expression with anti-LMO2 VH#576. A, various truncated forms of the LMO2 protein with deletion of the seven N-terminal amino acids and increasing truncation of the C terminus from two to 11 residues (see supplemental Fig. S3) were co-expressed in E. coli and co-purified as complex with His-tagged anti-LMO2 VH#576. B, the structural integrity of the heterodimer complex was analyzed by circular dichroism of purified VH and the truncated ΔLMO2(7N11C) complex. The data were deconvoluted with the CDSSTR method (45). CDSSTR-calculated content of various secondary structures were 8% α-helix, 62% β-structure, and 30% random coil.

The ability to produce high quantities of soluble LMO2-VH#576 heterodimer and the apparent quality of the tertiary structure of the complex suggested that crystal formation might be possible. Accordingly, protein crystallization was carried out, and initial screening of crystallization conditions yielded plate-like crystals or needle-shaped crystals within 2 days (supplemental Fig. S4, A and B) and confirmed these were as containing both LMO2 and VH#576 molecules in equal molarities (supplemental Fig. S4C). This method finding suggests that co-purification and co-crystallization of LMO2-VH proteins will allow us to take further optimized crystals to x-ray crystallographic analysis and that the general approach of single domain “coating” of recombinant protein could be applicable to other proteins that are intransigent to recombinant production systems.

IAC3-selected Single Domains Function in Mammalian Cells

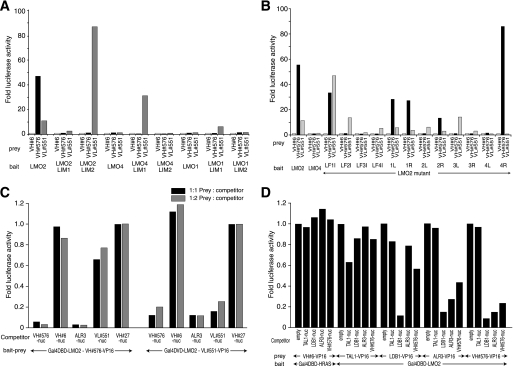

The IAC3 methods rely on the use of yeast as a counterpart intracellular environment to mammalian cells in which ultimately the antibody fragments will be used. To evaluate whether IAC3-selected single domains are also functional in mammalian cells, we tested both VH and VL single domains binding LMO2 using mammalian two-hybrid assays (Fig. 4). Two anti-LMO2 single domain clones VH#576 and VL#551 were cloned into the expression vector pEFVP16 to express VP16AD fusion proteins. CHO cells were transfected with constructs expressing single domain-VP16AD fusions and either LMO2 or other LIM domain-only (LMO) family proteins LMO1 or LMO4 fused to Gal4-DBD. Both of these single domains bind to the LMO2 bait in CHO cells. VH#576 specifically binds to the LMO2 bait comprising both LIM1 and LIM2 domains, but not to separate LIM1 or LIM2 domains of LMO2 (Fig. 4A). Conversely, VL#551 not only binds the LIM2 domain LMO2, but also to the LIM1 domains of LMO1 and LMO4.

FIGURE 4.

Characterization of anti-LMO2 single VH and VL domains using mammalian two-hybrid assays. Two hybrid assays were carried out using CHO cells or a CHO line with stable integration of the luciferase gene (CHOluc15 (8)) with various baits (Gal4-DBD-LMO2 fusions) and preys (iDAb-VP16 fusions) and in some cases in the presence of potential protein inhibitors of protein interaction. Interaction signals were measured by luciferase gene activation (assessed as fold luciferase activity compared with negative control using an irrelevant iDAb anti-RAS VH#6 prey (13) in A and B, anti-ATF2 VH#27 (4) as competitor in C, or no competitor in D). A, CHO cells were transiently transfected with plasmids expressing Gal4-DBD baits comprising LIM domain fragments of LMO1, LMO2, or LMO4 proteins and preys expressing anti-LMO2 VH#576 or VL#551 or VH#6 iDAbs fused to the VP16AD, together with luciferase reporters. B, determination of binding sites of single VH and VL domains with LMO2 LIM fingers. The chimeric LIM finger bait proteins (with ISL1 or LMO4 LIM finger sequences grafted into LMO2 and fused to Gal4-DBD (11) as shown in supplemental Fig. S3) were co-expressed with VH#576 or VL#551 iDAbs or VH#6 as negative control. L, left side sequence; R, right side sequence. C, competition assays between antibody fragments binding to LMO2. CHOluc15 cells were co-transfected with the triplex M2H vector co-expressing Gal4-DBD-LMO2 and VH#576-VP16 or VL#551-VP16 with competitor plasmids expressing either VH#576 or VL#551 iDAbs or an anti-LMO2 scFv ALR3 (11), or nonrelevant single iDAbs (VH#6 (4) and VH#27 (4)). The prey:competitor plasmid ratio was used in either a 1:1 or 1:2 molar ratio. D, competition assays between LMO2 and its partner protein interactions. CHO cells were co-transfected with Gal4-DBD-LMO2 and baits comprising the LMO2 partners TAL1, LDB1, or the VH#576 and ALR3 fused to the VP16AD, together with the competitor proteins indicated and Dual-Luciferase reporters. LDB1-VP16AD fusion was used at a 1:10 dilution.

Epitope mapping was carried out with each single domain (VH#576 and VL#551) using a series of LMO2 LIM finger replacement mutants (in which parts of the LIM fingers of LMO2 have been replaced by homologous parts of LMO4 or the LIM homeodomain family protein ISL1; see supplemental Fig. S3 and Fig. 4B) (11). VH#576 binding to LMO2 was abolished with LIM finger 2, 3, or 4 mutations, and VL#551 does not bind to LIM finger 3 or 4 mutants. The result suggests VH#576 binds a wider surface of the LMO2 protein, including the LIM1-LIM2 junction. Although VH#576 appears to bind LMO2 with stronger affinity than VL#551, their epitopes seem to overlap to some extent. This conclusion was supported by competition two-hybrid assays (Fig. 4C). The single domains or the anti-LMO2 scFv ALR3 (11) with nuclear localization signal constructs were transfected with the LMO2 bait and either anti-LMO2 VH#576 or VL#551 preys in CHO cells, and luciferase reporter activities were tested. VH#576 could inhibit the interaction of LMO2 and VL#551, and vice versa for VL#551. Interestingly, anti-LMO2 scFv ALR3 could also inhibit both LMO2-VH#576 and LMO2-VL#551 interactions. Furthermore, we also tested whether anti-LMO2 VH#576 could interfere with LMO2 and its partner interactions to form LMO2 multimer complexes (Fig. 4D). VH#576 inhibits LMO2-LDB1 interaction by up to 50% of reporter activity. This was also found for the reciprocal that LDB1 could interfere with anti-LMO2 VH#576 binding LMO2. This suggests that the anti-LMO2 VH#576 and LDB1 bind to LMO2 at overlapping sites or that either protein can induce a conformational change in LMO2 that precludes or inhibits the binding of the other protein.

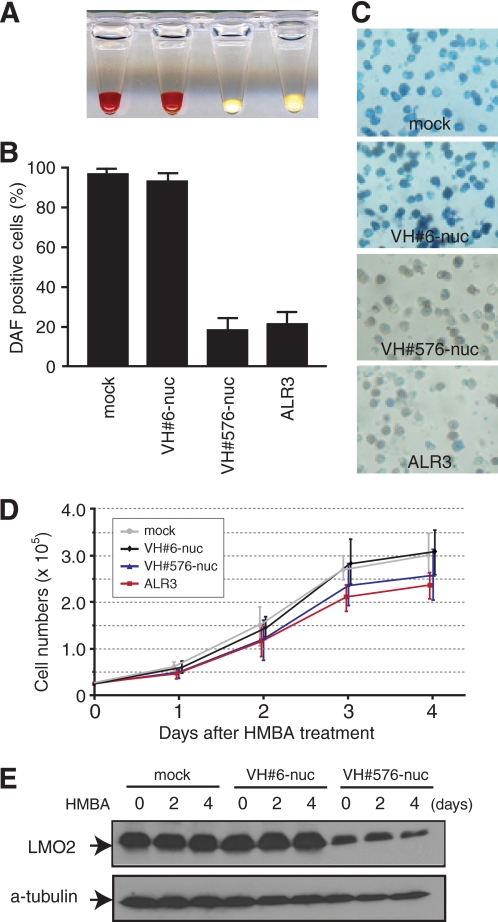

VH#576 Interferes with Lmo2 Function in Erythropoiesis

LMO2 is known to form multiprotein complexes involving LDB1, E47, TAL1, GATA-1 (22), and additional proteins and to regulate hematopoietic development (23) as gene targeting has shown a necessary function in primitive and definitive hematopoiesis (24). The cell-specific functions of LMO2 have not been well characterized previously due to lack of LMO2-specific reagents. We have now used the anti-LMO2 VH#576 to determine the biological effects of interfering with Lmo2 function in erythroid cell differentiation. MEL cells are erythroid precursors blocked at the proerythroblast stage (25, 26), and erythroid differentiation can be induced (manifest by hemoglobinization) by treatment of MEL cells with HMBA (26, 27). MEL cells were infected with recombinant retrovirus expressing anti-LMO2 VH#576 or ALR3 or anti-RAS VH#6 with nuclear localization signal, plus a GFP reporter. Infected cells expressing GFP were sorted by flow cytometry and treated with 4 mm HMBA for 4 days. After this period of HMBA treatment, cells were stained with DAF, reflecting hemoglobin production in the cells (Fig. 5A). We observed that HMBA-treated MEL cells expressing anti-LMO2 VH#576 or ALR3 were suppressed in hemoglobin production (only ∼20% of cells stained with DAF compared with those expressing the anti-RAS VH or infected with virus only; Fig. 5, A–C). Cell growth characteristics were unaffected by expressing iDAbs in the nucleus (Fig. 5D) and immunoblotting with anti-LMO2 mAb demonstrated that anti-LMO2 VH#576 has a moderate effect on Lmo2 protein levels (Fig. 5E). These data show that the VH#576 iDAb is an effective anti-Lmo2 agent and that the erythroid differentiation, discernible by hemoglobinization of MEL cells, is dependent on Lmo2 function. One important facet of this Lmo2 function is its interaction with Ldb1 because the VH576 has an inhibitory effect on Lmo2-Ldb1 interaction (Fig. 4D).

FIGURE 5.

Effect of anti-LMO2 intracellular antibodies on HMBA-induced erythroid differentiation of MEL cells. MEL clone 585 cells (46) were infected with a bicistronic retrovirus expressing GFP together with anti-LMO2 iDAb VH#576, anti-LMO2 scFv ALR3, or a single domain recognizing RAS (VH#6). The antibody fragments each had a nuclear localization signal (nuc). Forty-eight hours after infection, GFP-expressing cells were sorted by flow cytometry and cultured in the presence of 4 mm HMBA. Four days later, the cells were harvested, and hemoglobinization was assessed by red coloration of cell pellets (A). Staining with DAF was used for quantification of hemoglobin production in cells (B and C). Error bars represent S.D. Cell viability during HMBA treatment was assessed daily with trypan blue staining (three independent experiments; error bars, S.D) (D). The levels of LMO2 protein were assessed during the HMBA-differentiation process by Western blot analysis using anti-LMO2 monoclonal antibody (19) (E). The arrowheads indicated approximate 18-kDa LMO2 bands. α-Tubulin protein levels served as internal controls.

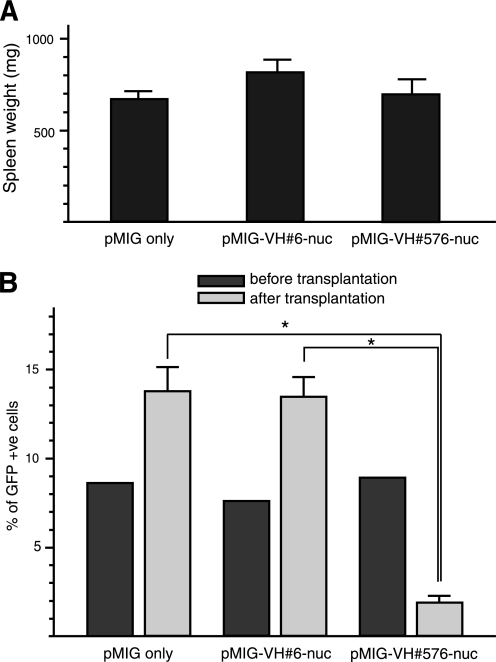

VH#576 Hinders LMO2-dependent T-cell Neoplasia

LMO2 was originally discovered because it is activated in T-cell acute leukemia by chromosomal translocations (28, 29) and, using macrodrugs such as scFv and peptide aptamers, we have shown that it is required for tumor growth in transgenic mouse models of Lmo2-dependent neoplasia (11, 30). We sought to further validate the anti-LMO2 VH#576 utilizing the same neoplasia assay, and we can now begin to evaluate the specific role of particular partner proteins in the Lmo2-directed tumor formation and maintenance. Neoplastic T-cells from Lck-Lmo2 transgenic mice were infected with retrovirus expressing either VH#576 or anti-RAS VH#6 nuclear localization signal, along with GFP, and cells were transplanted into recipient nude mice. After splenomegaly arose in these recipients (comparable spleen weights that we found in recipients injected with virus-only, anti-RAS, and anti-LMO2-infected cells; Fig. 6A), the spleen cells were harvested, and the percentage of cells expressing GFP from the virus was determined by flow cytometry in comparison to the initial infected populations (Fig. 6B). In these assays, we observed an 80% inhibition of growth of VH#576-infected cells compared with controls where the percent of GFP-expressing cells tended to increase compared with starting cell populations. There are three conclusions. LMO2 is necessary for overt T-cell tumorigenesis, the anti-LMO2 VH#576 is a potential anti-LMO2 macrodrug, and the IAC3 method is efficacious for selecting functionally useful intracellular antibody fragments.

FIGURE 6.

Anti-LMO2 VH#576 inhibits T-cell neoplasia in a nude mouse transplantation assay. Neoplastic T-cells from an Lck-Lmo2 transgenic mouse thymoma were infected with a retrovirus expressing GFP (pMIG only) or bicistronic vectors expressing anti-LMO2 VH#576 with a nuclear localization signal (pMIG-VH#576-nuc) and GFP or anti-RAS VH#6 with nuclear localization signal (pMIG-VH#6-nuc) and GFP. The percentages of infected cells were determined by assessing the proportion of GFP-expressing cells using flow cytometry. A bolus of one million T-cells from the infected population was injected into the tail vein of recipient CD1 nu/nu mice and mice were sacrificed at 4–6 weeks after injection. In all recipients, splenomegaly was observed, and comparable weights of enlarged spleens were found (A). Single T-cell suspensions were prepared from the recipient mouse spleens, and GFP expression was assessed by flow cytometry (B). The histogram displays the percentage of GFP-expressing T-cells before transplantation (black boxes) and after transplantation (gray boxes). Data show S.E. from n = 9 (pMIG-only transplanted mice), n = 10 (pMIG-VH#6-nuc-transplanted mice) and n = 10 (pMIG-VH#576-nuc-transplanted mice). p values of <0.001 were determined as differences between either pMIG-VH#576-nuc-transplanted mice and pMIG only or pMIG-VH#576-nuc-transplanted mice and pMIG-VH#6-nuc (t test).

DISCUSSION

Advantages of IAC3 Library Approach to Single Domain Intracellular Antibodies

A key feature of effective isolation of antigen-specific intracellular antibody fragments as iDAbs is to screen with high diversity antibody libraries, which are described in this work. The IAC3 method has several advantages compared with other antibody selection approaches, but a critical advantage is that it obviates the preparation of a purified antigen protein and allows the isolation of iDAbs binding to the native conformation of antigen, thus suitable for in-cell use. This feature is complemented by the use of a consensus single scaffold for VH and VL based on optimal intracellular folding that does not require the intrachain disulfide bond (5) naturally occurring in variable region domains. Furthermore, the limitation that direct screening imposes on the diversity of iDAb libraries is overcome in IAC3 by use of initial libraries with diversity only in CDR3 and subsequent “affinity maturation” by successive selections of sublibraries randomized in CDR2 and then CDR1, which achieves overall high diversity library screening.

Our screening data shows that VH or VL iDAbs can be isolated using varied types of antigen ranging from transcription factors that bind to DNA, a protein that is involved formation of in transcription protein complexes or protein involved in signal transduction (LMO2, TP53, Hoxa9-HD, and CRAF1-RBD, respectively). These iDAbs can serve as valuable tools for biological and functional genomic research with similar effectiveness, but different principles, to RNA interference knockdown technologies. Examination of the CDR sequences of the isolated iDAbs shows various properties of the resultant single domains that emanate from the IAC3 screens. For instance, >100 clones of the anti-TP53 VHs were isolated particularly from the initial VP16*-VH13rdm library, yet only one CDR3 type emerged from the second and third sublibrary screens. The CDR1 and CDR2 sequences vary, whereas the CDR3 is invariant. It is interesting that this CDR3 sequence has a CXXC motif (CERC) that might bind to TP53 in the zinc-binding region of the DNA binding domain (31). Further sublocation of the iDAb binding to TP53 would allow the binding site location to be evaluated. Similar to this are the anti-LMO2 VL clones, which have a CXXC or HXXC motif in CDR2 (Fig. 2), and an analogous phenomenon has been reported for anti-LMO2 VL segments, which may be iDAbs that bind to zinc-binding regions of LMO2. A related effect was found with an anti-LMO2 peptide aptamer described previously that seems to interact with the zinc in LMO2 LIM finger 4 (30).

IAC3-derived Single Domains Facilitate Recombinant Protein Production for Structural Analysis

X-ray crystallography is a key technique in facilitating the determination of the structures of many important proteins and complexes to help elucidate biological mechanisms. However, the crystal structures of many molecules, including membrane proteins, still remain unsolved because either bulk of protein with high purity is difficult to make in soluble form, and/or the structure of single proteins are too disordered to facilitate crystal formation. Thus, one rate-limiting step is preparation of bulk protein samples with enough stability. For instance, recombinant LMO2 produced in bacteria is known to be unstable and insoluble in solution (32–34). The structure of the LIM domain-only family member protein LMO4 has only been solved in the form of a LMO4-LDB1 chimeric protein designated as FLINC4, in which there is stabilized interaction of LMO4 and LDB1-LIM domain binding region (35). By co-expressing and co-crystallizing of LMO2 and VH#576, we have been able to make stabilized and soluble LMO2 because of its binding with the single domain. A similar observation has been reported with MDM2 using MDM2-specific DAb (36). As our single domains selected from IAC3 libraries were optimized for intracellular production and activity, these antibody fragments can potentially be applicable to co-production with other unstable recombinant proteins in bacteria to express high yield of proteins. In addition, the single domains selected by IAC are based on their ability to bind the native conformation of target antigens with high affinity. These should facilitate recombinant protein production for difficult proteins and co-crystallization by stabilizing with antibody fragment, for example of stable membrane-antibody complex (37, 38). This approach also has the potential to improve the crystallization of a target protein as the strong and specific noncovalent bonds, which form between the iDAb and target protein, restrict the dynamics of flexible domains. Interactions between the iDAb and target protein can also help to increase the hydrophilicity of the complex and maintain the protein in a more monodisperse solution. Furthermore, immunoglobulin fragments including single variable domains have a known structure (39, 40), and this can be advantageous in crystallization studies through the use of molecular replacement, providing molecular phasing information for the target protein complex.

iDAb-mediated Dissection of LMO2 Protein Interactions Defines Mandatory Roles for LMO2-LDB1

The LMO2 protein can directly interact with LDB1/NLI, SCL/TAL1, GATA1/2 (22, 41), and other components (33, 42, 43), forming a multicomplex that regulates gene expression through binding GATA and E-box sites in hematopoiesis (22, 41). In addition, structural data of FLIN2, an intramolecular LMO2-Ldb1 fusion protein, shows at least the LIM1 domain of LMO2 interacts with LDB1 (44). Competitive M2H analysis showed that the VH#576 was able to partly interfere with the LDB1-LMO2 interaction but not TAL1-LMO2. LDB1 was able to efficiently compete VH#576 binding as, paradoxically, also did the previously identified neutralizing anti-LMO2 scFv ALR3 (11). VL#551 binding is depleted by all of the LMO2 natural partners and the antibody binders. At face value, this implies that the LMO2 interface, which binds VH#576, VL#551, and ALR3 scFv, is overlapping with the binding surface of LDB1, especially because we found that VH#576 binds across fingers 2, 3, and part of 4, and ALR3 binds to finger 3 and part of finger 4 (11). However, the M2H assay is a surrogate assay for binding, and only binding on the linear sequence can truly be assessed. If the binding of two proteins has structural consequences, there could be effects on the binding of other components of the complex. The final dissection of the binding sites must await structural studies of free LMO2, LDB1, and VH. This has been difficult thus far due to the intransigence to production of LMO2 protein; however, employing the LMO2-VH#576 heterodimer, we have begun to develop soluble LMO2 and preliminary co-crystals have been obtained that should make structural resolution of LMO2 possible. We have employed the VH fragment VH#576 to ascertain the importance of the LMO2-LDB1 interaction during the function of LMO2 in two LMO2-dependent settings (i.e. hematopoiesis and T-cell neoplasia). We have shown previously that Lmo2 is necessary for primitive erythropoiesis and definitive hematopoiesis (23, 24). We have now addressed the question of whether the Lmo2-Ldb1 heterodimer is required in the hemoglobinization steps during the differentiation steps of MEL erythroid cells in vitro (27). We showed that anti-LMO2 VH#576 could prevent hemoglobinization in these cells (Fig. 5). This inhibitory effect on the differentiation process occurs without substantial inhibition of cell growth and only a small diminution of the level of Lmo2 protein. We draw two conclusions, first, that Lmo2 is a required protein for the late stages of erythropoiesis as evident in MEL cells and second, that Lmo2-Ldb1 protein interactions are needed for this process.

The LMO2 gene was originally discovered by its association with chromosomal translocations in T-cell leukemia (28, 29), and later, we developed an Lmo2-dependent gain of function transgenic model in which the mice develop clonal T-cell neoplasia (11). This model was used to validate the Lmo2 protein as a cancer therapy target using anti-LMO2 peptide aptamer (30) and anti-LMO2 scFv ALR3 (11). Here, we have shown anti-LMO2 iDAb VH#576 can impede Lmo2-dependent neoplastic growth in recipient mice by a mechanism that operates, directly or indirectly, by affecting the Lmo2-Ldb1 interaction. Our data thus show that this intermolecular interaction is critical for function in two distinct settings. Finally, these results with VH#576, and previous data with anti-RAS VH (13), demonstrate that the IAC3 strategy is effective for selecting functional iDAbs with the ability to interfere with protein function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are indebted Thomas Walter and the Oxford Protein Production Facility for protein crystallization trials and to professor D. R. Higgs and Dr. B. Wood for MEL 585 cells and professor R. Levy for anti-LMO2 monoclonal antibody.

This work was supported by grants from the Medical Research Council, from Leukemia and Lymphoma Research, and from the Leeds Institute of Molecular Medicine (University of Leeds).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4.

L. Drynan, A. Forster, and T. H. Rabbitts, unpublished data.

- VH

- immunoglobulin heavy chain variable domain

- AD

- activation domain

- CDR

- complementarity determining region

- DAF

- diaminofluorene

- DBD

- DNA binding domain

- HMBA

- hexamethylene bisacetamide

- IAC

- intracellular antibody capture

- DAb

- single domain antibody fragment

- iDAb

- intracellular single domain antibody fragment

- MEL

- murine erythroleukemia

- scFv

- single chain variable fragment

- M2H

- mammalian two-hybrid

- luc

- luciferase

- RBD

- RAS binding domain

- V region

- immunoglobulin variable region

- VL

- immunoglobulin light chain variable domain

- HD

- homeodomain.

REFERENCES

- 1. Reichert J. M., Rosensweig C. J., Faden L. B., Dewitz M. C. (2005) Nat. Biotechnol. 23, 1073–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Visintin M., Meli G. A., Cannistraci I., Cattaneo A. (2004) J. Immunol. Methods 290, 135–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pérez-Martínez D., Tanaka T., Rabbitts T. H. (2010) Bioessays. 32, 589–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tanaka T., Lobato M. N., Rabbitts T. H. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 331, 1109–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tanaka T., Rabbitts T. H. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 376, 749–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Colby D. W., Chu Y., Cassady J. P., Duennwald M., Zazulak H., Webster J. M., Messer A., Lindquist S., Ingram V. M., Wittrup K. D. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 17616–17621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tanaka T., Rabbitts T. H. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 1025–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tanaka T., Rabbitts T. H. (2010) Nature Protocols 5, 67–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Visintin M., Tse E., Axelson H., Rabbitts T. H., Cattaneo A. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 11723–11728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tse E., Lobato M. N., Forster A., Tanaka T., Chung G. T., Rabbitts T. H. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 317, 85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nam C. H., Lobato M. N., Appert A., Drynan L. F., Tanaka T., Rabbitts T. H. (2008) Oncogene 27, 4962–4968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tanaka T., Chung G. T., Forster A., Lobato M. N., Rabbitts T. H. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tanaka T., Williams R. L., Rabbitts T. H. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 3250–3259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tanaka T., Rabbitts T. H. (2009) Nucleic. Acids Res. 37, e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fearon E. R., Finkel T., Gillison M. L., Kennedy S. P., Casella J. F., Tomaselli G. F., Morrow J. S., Van Dang C. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 7958–7962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sadowski I., Bell B., Broad P., Hollis M. (1992) Gene. 118, 137–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Refaeli Y., Van Parijs L., Alexander S. I., Abbas A. K. (2002) J. Exp. Med. 196, 999–1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morita S., Kojima T., Kitamura T. (2000) Gene. Ther. 7, 1063–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Natkunam Y., Zhao S., Mason D. Y., Chen J., Taidi B., Jones M., Hammer A. S., Hamilton Dutoit S., Lossos I. S., Levy R. (2007) Blood 109, 1636–1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miroux B., Walker J. E. (1996) J. Mol. Biol. 260, 289–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lefranc M. P., Pommié C., Ruiz M., Giudicelli V., Foulquier E., Truong L., Thouvenin-Contet V., Lefranc G. (2003) Dev. Comp. Immunol. 27, 55–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wadman I. A., Osada H., Grütz G. G., Agulnick A. D., Westphal H., Forster A., Rabbitts T. H. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 3145–3157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Warren A. J., Colledge W. H., Carlton M. B., Evans M. J., Smith A. J., Rabbitts T. H. (1994) Cell 78, 45–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yamada Y., Warren A. J., Dobson C., Forster A., Pannell R., Rabbitts T. H. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 3890–3895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marks P. A., Rifkind R. A. (1978) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 47, 419–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Friend C., Scher W., Holland J. G., Sato T. (1971) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 68, 378–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reuben R. C., Wife R. L., Breslow R., Rifkind R. A., Marks P. A. (1976) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 73, 862–866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Boehm T., Foroni L., Kaneko Y., Perutz M. F., Rabbitts T. H. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 4367–4371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Royer-Pokora B., Loos U., Ludwig W. D. (1991) Oncogene. 6, 1887–1893 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Appert A., Nam C. H., Lobato N., Priego E., Miguel R. N., Blundell T., Drynan L., Sewell H., Tanaka T., Rabbitts T. (2009) Cancer Res. 69, 4784–4790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pavletich N. P., Chambers K. A., Pabo C. O. (1993) Genes. Dev. 7, 2556–2564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Archer V. E., Breton J., Sanchez-Garcia I., Osada H., Forster A., Thomson A. J., Rabbitts T. H. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 316–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ryan D. P., Duncan J. L., Lee C., Kuchel P. W., Matthews J. M. (2008) Proteins 70, 1461–1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Deane J. E., Sum E., Mackay J. P., Lindeman G. J., Visvader J. E., Matthews J. M. (2001) Protein Eng 14, 493–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Deane J. E., Maher M. J., Langley D. B., Graham S. C., Visvader J. E., Guss J. M., Matthews J. M. (2003) Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 59, 1484–1486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yu G. W., Vaysburd M., Allen M. D., Settanni G., Fersht A. R. (2009) J. Mol. Biol. 385, 1578–1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Röthlisberger D., Pos K. M., Plückthun A. (2004) FEBS Lett. 564, 340–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ostermeier C., Iwata S., Ludwig B., Michel H. (1995) Nat. Struct. Biol. 2, 842–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ruiz M., Lefranc M. P. (2002) Immunogenetics 53, 857–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ramsland P. A., Farrugia W. (2002) J Mol. Recognit 15, 248–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Grütz G. G., Bucher K., Lavenir I., Larson T., Larson R., Rabbitts T. H. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 4594–4605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bégay-Müller V., Ansieau S., Leutz A. (2002) FEBS Lett. 521, 36–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mao S., Neale G. A., Goorha R. M. (1997) Oncogene. 14, 1531–1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Deane J. E., Mackay J. P., Kwan A. H., Sum E. Y., Visvader J. E., Matthews J. M. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 2224–2233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Manavalan P., Johnson W. C., Jr. (1987) Anal. Biochem. 167, 76–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Deisseroth A., Hendrick D. (1978) Cell 15, 55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.