Abstract

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6), which plays a critical role in immune responses, is activated by interleukin-4 (IL-4). Activity of STAT family members is regulated primarily by tyrosine phosphorylations and possibly also by serine phosphorylations. Here, we report a previously undescribed serine phosphorylation of STAT6, which is activated by cell stress or by the pro-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-1β (IL-1β). Our analyses suggest that Ser-707 is phosphorylated by c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK). Phosphorylation decreases the DNA binding ability of IL-4-stimulated STAT6, thereby inhibiting the transcription of STAT6-responsive genes. Inactivation of STAT6 by JNK-dependent Ser-707 phosphorylation may be one mechanism of controlling the balance between IL-1β and IL-4 signals.

Keywords: Cytokine, JNK, MAP Kinases (MAPKs), Phosphorylation Enzymes, Phosphotyrosine Signaling, Signal Transduction, STAT Transcription Factor

Introduction

STAT proteins are transcription factors that are activated by a variety of cytokines and growth factors. Seven mammalian STAT proteins have been identified, which contain a conserved structure composed of SH2, DNA binding, and trans-activation domains. Extracellular binding of cytokines or growth factors to the receptors of these STAT proteins induces the activation of intracellular Janus kinases (JAK), which phosphorylate STAT proteins on a specific tyrosine residue. The phosphorylated STAT proteins promote formation of homo- or heterodimers from the phosphorylated tyrosine residue and its partner SH2 domains. The dimers are transported into the nucleus, where they induce transcription of the target genes (1–4). One of the seven STAT proteins, STAT6, was originally cloned as an IL-4-activated transcription factor (5). Studies of STAT6-deficient mice showed that STAT6 plays key roles in the differentiation of TH2 cells, the switching of B-cell immunoglobulin isotype to IgE, and the induction of allergic disease (6–9).

The mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) include three families of serine/threonine-protein kinases: extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), JNK, and p38. JNK and p38 are activated by environmental stress and pro-inflammatory cytokines. JNK, also known as stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK), is activated by IL-1, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), UV radiation, osmotic stress, anisomycin, and other stress factors (10–14). JNK activation leads to Ser/Thr phosphorylation of several transcription factors and other cellular substrates that are implicated in cell survival, insulin receptor signaling, and mRNA stabilization (15–19).

In addition to the tyrosine phosphorylations, those of serine residues are also important for regulation of STAT activities. The serine residue in a conserved Pro-X-Ser-Pro sequence at the COOH termini of STAT1, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5a, and STAT5b is phosphorylated in response to cytokines and growth factors (20–23). Serine phosphorylation of STAT6 has also been demonstrated. Following IL-4 stimulation, Ser-756 in the transactivation domain of STAT6 is concurrently phosphorylated with Tyr-641, which is essential for the activation of STAT6 (24). However, the biological significance of this phosphorylation remains unclear. Phosphorylation of other multiple serine residues at unspecified locations in the transactivation domain of STAT6 has also been detected, following treatment of cells with protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A)2 inhibitors, such as calyculin A (25, 26). These serine phosphorylations led to reduced transcriptional activity of STAT6. Despite the previous findings, the biological roles of serine phosphorylations in STAT6 and the specific kinases involved are not clear. Results of the present study show that Ser-707 in the transactivation domain of STAT6 is directly phosphorylated by JNK in response to stress treatments or IL-1β stimulation. Ser-707 phosphorylation appears to play a role in a crosstalk between the intracellular signals of IL-4 and IL-1β by negatively regulating IL-4-induced transcriptional activation of STAT6.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Transfection

Human HeLa cells and HEK293 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin (50 units/ml and 50 μg/ml, respectively) at 37 °C, under humidified 5% CO2. For transient transfection studies, the cells were transfected with an expression plasmid of STAT6 or its mutants, using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). All analyses were performed 24 h after transfection.

Antibodies and Reagents

The following primary antibodies were used: anti-pY-STAT6, anti-JNK, anti-ERK, and anti-AKT (Cell Signaling Technology); anti-STAT6, anti-actin, and anti-PARP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); anti-Flag (Sigma-Aldrich); and anti-Myc (Novus Biologicals). Recombinant human IL-4, IFN-γ, and IL-1β (PeproTech) were used at final concentrations of 10 ng/ml. Anisomycin, MG-132, SB202190, and SP600125 were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Nocodazole, taxol, colchicine, and calyculin A were obtained from Wako Chemicals.

Plasmid Constructs

The cDNA of full-length STAT6 was cloned into pCMV-3Tag-1A (Flag-tagged) and pCMV-3Tag-9 (Myc-tagged) (Stratagene). For overexpression experiments, five alanine substitution mutants of STAT6 (T168A, S583A, T658A, S707A, and S756A) were obtained by overlap PCR from STAT6 cDNA.

In Vitro Phosphatase Assay

Whole cell lysates (50 μg) from anisomycin-treated HeLa cells were prepared in a phosphatase reaction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 9.0, 1 mm MgCl2) and incubated with alkaline phosphatase (CIAP: 10 units) for 30 min at 30 °C in the presence or absence of phosphatase inhibitors. The reactions were terminated by adding an SDS sample buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by Western blotting.

In Vitro Kinase Assay

cDNA encoding, human STAT6621–847 or ATF21–109 was inserted into pET41a expression vector (Novagen). Their GST fusion proteins were induced in BL21 cells of Escherichia coli by adding 0.4 mm isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, and were purified by glutathione-Sepharose 4B (Amersham Biosciences). Five micrograms of GST-STAT6621–847 or GST-ATF21–109 were incubated with 100 ng of JNK1 (Carna Biosciences, Inc.) or p38α (Upstate Biotechnology) for 30 min at 30 °C in 30 μl of kinase buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mm MgCl2, 2 mm DTT, 5 mm NaF, 0.2 mm Na3VO4, 3 μCi [γ-32P]ATP). The kinase reactions were terminated by adding an SDS sample buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by autoradiography.

Electrophoretic Gel Mobility-Shift Assay

For electrophoretic gel mobility-shift assays, HeLa or HEK293 cells were lysed in buffer C (20 mm HEPES, 25% glycerol, 0.42 m NaCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm EDTA). Twenty micrograms of the cell lysates were incubated with 200 ng of poly-dI-dC (Sigma-Aldrich) and 32P-labeled N6-GAS oligonucleotide (5′-GATCGCTCTTCTTCCCAGGAACTCAATG) (5) for 30 min on ice in 15 μl of a reaction buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, 1 m NaCl, 0.1 m EDTA, 0.1 m DTT, 37.6% glycerol, 1.5% Nonidet P-40, 5 mg/ml BSA). The samples were separated by 4% (w/v) Tris borate EDTA (TBE)-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography.

Cross-linking Experiments

HeLa cells grown on 6-well plates were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (150 mm NaCl, 10 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.4) and collected into a lysis buffer (phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% Triton X-100). The cell lysates were incubated with or without disuccinimidyl suberate (DSS, 0.5 mm) for 30 min on ice. The reaction was stopped by adding 4 mm glycine. The cross-linked products were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting.

Immunoprecipitation of STAT6 Homodimers

HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors of Flag-tagged and Myc-tagged STAT6. The transfected cells were treated with 1% (v/v) DMSO or 500 ng/ml anisomycin for 1 h, then stimulated with 10 ng/ml IL-4 for 30 min. The cells were lysed in buffer C and centrifuged at 65,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was incubated with anti-c-Myc agarose beads (Sigma) at 4 °C for 2 h. Bound fractions were eluted with an SDS sample buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-Flag antibody.

Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extracts

HeLa cells cultured on 100 mm dishes were transferred into 1 ml of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline. The cells were centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min and lysed in 150 μl of low salt buffer (10 mm HEPES, 10 mm KCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, and 0.5 mm DTT) on ice. After a 20-min incubation, the cell suspension was homogenized by passage through a 27-gauge needle. The supernatant was collected as a cytoplasmic extract after centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The nuclear pellet was resuspended in buffer C and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was saved as a nuclear extract.

Reverse Transcription PCR

Total cellular RNA was extracted with QIAshredder (Qiagen) and further isolated with an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). First-strand cDNAs were synthesized using Superscript II (Invitrogen) and amplified using the following primers: 5′-GGAACTGCCACACGTGGGAGTGAC and 5′-CTCTGGGAGGAAACACCCTCTCC for Eotaxin-3 (CCL26); 5′-CACGCACTTCCGCACATTCC and 5′-TCCAGCAGCTCGAAGAGGCA for SOCS-1; 5′-CTCAAGACCTTCAGCTCCAA and 5′-TTCTCATAGGAGTCCAGGTG-3′ for SOCS-3; 5′-GACCACAGTCCATGCCATCACT and 5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAG for GAPDH.

RESULTS

Cell Stress Induces Phosphorylation of STAT6 in HeLa Cells

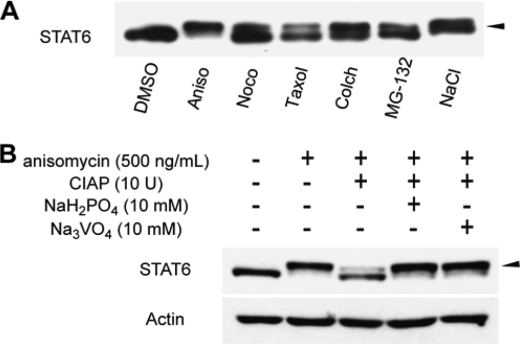

During the course of our investigation, we discovered a mobility shift of STAT6 in Western blot analyses of HeLa cells treated with a range of bioactive small molecules. Among thirteen molecules with distinct pharmacological effects, anisomycin (a protein synthesis inhibitor), nocodazole and cholchitin (microtubule inhibitors), taxol (a microtubule stabilizer), and MG-132 (a proteasome inhibitor) exhibited clear band shifts or doublet formations of STAT6 bands on an SDS gel (Fig. 1A). In particular, 500 ng/ml of anisomycin induced a complete band shift of STAT6. The pharmacological diversity of these five molecules suggested that the mobility shift might be induced by cell stress. Indeed, 0.5 mm NaCl, an osmotic stress inducer, produced a band shift similar to that produced by anisomycin.

FIGURE 1.

Bioactive small molecules induce phosphorylation of STAT6. A, treatment with several bioactive compounds induced a STAT6 mobility shift. HeLa cells were incubated with DMSO, anisomycin (Aniso; 500 ng/ml, 1 h), nocodazole (Noco; 80 ng/ml, 16 h), taxol (500 nm, 16 h), colchicine (Colch; 200 nm, 16 h), MG-132 (10 μm, 16 h), or NaCl (0.2 m, 1 h). Whole cell lysates were separated by 5% SDS- polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-STAT6 antibody. Arrow shows a mobility shift band. B, effects of CIAP treatment on a STAT6 mobility shift. Whole cell lysates from anisomycin-treated HeLa cells were reacted with CIAP or co-reacted with CIAP and phosphatase inhibitor, NaH2PO4 or Na3VO4. The reaction mix was separated by 5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by Western blotting, using anti-STAT6 antibody (upper panel) or anti-β-actin (lower panel). β-Actin served as a loading control. The arrow shows a mobility shift band.

The band shift implied post-translational modification of STAT6 upon cell stress. A number of post-translational modifications are known to exhibit such band shifts and induce biologically significant outputs, including phosphorylation, acetylation, glycosylation, and ubiqutination (27–30). We hypothesized that the stress-induced post-translational modification plays a role in the regulation of STAT6. Our further studies used anisomycin as an inducer of the modification of STAT6, because anisomycin induced a most prominent band shift on an SDS gel (Fig. 1A).

Phosphorylation is the most general post-translational modification that often induces an upper band shift. Therefore, we performed in vitro phosphatase assays, in which whole cell lysates from anisomycin-treated HeLa cells were treated with CIAP, a universal protein phosphatase. The phosphatase treatment converted the slower-migrating band back to the faster-migrating band. In contrast, co-treatment of cells with CIAP and a phosphatase inhibitor (Na2PO4 or Na3VO4) restored the slower-migrating band (Fig. 1B). Thus, the band shift caused by anisomycin did appear to be due to protein phosphorylation.

JNK Directly Phosphorylates Ser-707 of STAT6

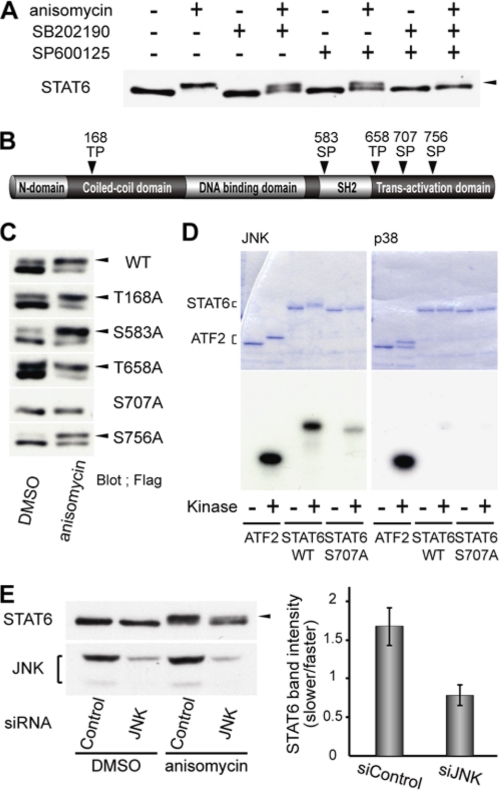

Cell stress inducers, including anisomycin, activate the protein kinases, p38 and JNK (31, 32). Therefore, we examined the effects of two kinase inhibitors, SB202190 for p38 and SP600125 for JNK, on the band shift of STAT6. Co-treatment of cells with anisomycin and either inhibitor converted the slower-migrating band to the faster-migrating band (Fig. 2A). Co-treatment of cells with anisomycin and both inhibitors completely shifted STAT6 back to the faster-migrating band.

FIGURE 2.

STAT6 Ser-707 is directly phosphorylated by JNK. A, effects of kinase inhibitor, SB202190 for p38 and SP600125 for JNK, on phosphorylation of STAT6. The levels of phosphorylation of STAT6 were observed as a mobility shift. HeLa cells were co-treated for 1 h with anisomycin (500 ng/ml) and SB202190 (10 μm), SP600125 (20 μm), or both inhibitors. The whole cell lysates were separated by 5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by Western blotting, using anti-STAT6 antibody. The arrow shows a mobility shift band. B, schematic representation of STAT6 and potential sites of phosphorylation by MAPK. C, effects of anisomycin treatment on the phosphorylation of Flag-STAT6WT (wild-type) and five Flag-STAT6 mutants, T168A, S583A, T658A, S707A, and S756A, transiently expressed in HeLa cells. The HeLa cells were incubated with DMSO or anisomycin (500 ng/ml) for 1 h. The levels of phosphorylation of STAT6 and its mutants were observed as a mobility shift. STAT6 and its mutants were detected by using anti-Flag antibody. The upper arrow shows GST-STAT6 and lower arrow shows GST-ATF2. D, in vitro kinase assay of recombinant GST-STAT6 protein by purified active JNK and p38. Purified GST-ATF2 (lanes 1 and 2), GST-STAT6WT (lanes 3 and 4) and GST-STAT6S707A (lanes 5 and 6) were incubated in the presence or absence of purified active JNK (left panel) or p38 (right panel), separated by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and analyzed by Coomassie staining (upper panel) and autoradiogram (lower panel). E, effects of JNK knockdown on Ser-707 phosphorylation of STAT6. JNK siRNA or control siRNA were transfected in HeLa cells, which were incubated with DMSO or anisomycin (500 ng/ml) for 1 h. The levels of phosphorylation of STAT6 were observed as a mobility shift. The expression levels of endogenous JNK were analyzed by Western blotting, using anti-JNK antibody. STAT6 (left upper panel) and JNK (left lower panel) are shown. Quantification of slower-migrating bands in anisomycin-treated cells (right panel). Values are means ± S.D. of three independent experiments. The arrow shows a mobility shift band.

p38 and JNK usually phosphorylate Ser/Thr-Pro sequences, and STAT6 has five such sequences (Fig. 2B). To determine whether any of the five potential sites are phosphorylated in cells treated with anisomycin, we transiently expressed five alanine-substitution mutants of STAT6 (T168A, S583A, T658A, S707A, and S756A) in HeLa cells. Cells transfected with an expression plasmid encoding WT or mutant STAT6 were treated with anisomycin for 1 h, and whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blots. Of the five mutants, only S707A failed to exhibit a mobility shift in the presence of anisomycin (Fig. 2C). These results suggested that p38 and/or JNK phosphorylate STAT6 at Ser-707.

To test this hypothesis, we performed an in vitro kinase assay using purified recombinant proteins. Kinase activity of p38 and JNK was verified by phosphorylation of a GST-tagged NH2-terminal fragment of ATF2 (amino acids 1–109), a known substrate of p38 and JNK (33). Ser-707 of STAT6 is located in the transactivation domain (amino acids 621–847), so we prepared a GST-tagged transactivation domain of STAT6 (GST-STAT6) and determined whether or not this fusion protein is phosphorylated by p38 or JNK. Recombinant JNK did phosphorylate GST-STAT6 and shifted its band on an SDS gel; recombinant p38 failed to do so (Fig. 2D). We also prepared a Ser-707-mutated version of GST-STAT6 and used it as a substrate. JNK showed little, if any, phosphorylation of this Ser-707 mutant and failed to induce a band shift. These results indicated that Ser-707 in STAT6 is directly phosphorylated by JNK, and that the phosphorylation of Ser-707 induces a mobility shift of STAT6 on an SDS gel.

We further examined the phosphorylation of STAT6 induced by anisomycin, using siRNA knockdown of JNK. Transient knockdown of JNK converted the slower migrating band to the faster migrating band, and the percentages of the slower migrating band decreased, while the faster-migrating band increased (Fig. 2E). These results confirmed that STAT6 is directly phosphorylated at Ser-707 by JNK in cells treated with anisomycin.

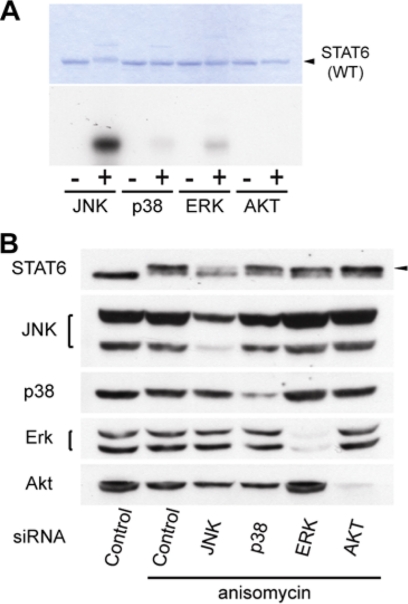

JNK Specifically Phosphorylates Ser-707 of STAT6

To confirm that JNK is a specific kinase for the phosphorylation of Ser-707, we performed two series of experiments. First, ERK, another Ser/Thr MAP kinase, and AKT, a major Ser/Thr protein kinase, were tested for their ability to phosphorylate STAT6 in vitro, in addition to p38 and JNK. Only JNK exhibited strong phosphorylation (Fig. 3A). Second, each of the four Ser/Thr protein kinases was transiently knocked down by siRNA. Although all of the siRNAs reduced the expression of corresponding kinases at comparable levels, only the siRNA of JNK blocked the STAT6 band-shift induced by anisomycin (Fig. 3B). These results indicated that Ser-707 of STAT6 is specifically phosphorylated by JNK.

FIGURE 3.

Specificity of kinases for Ser-707 phosphorylation of STAT6. A, purified GST-STAT6WT was incubated in the presence or absence of purified active JNK (lanes 1 and 2), p38 (lanes 3 and 4), ERK (lanes 5 and 6), or AKT (lanes 7 and 8). Products were separated on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and analyzed by Coomassie staining (upper panel) or autoradiogram (lower panel). B, effects of JNK, p38, ERK, or AKT knockdown on Ser-707 phosphorylation of STAT6. siRNAs were transfected into HeLa cells, which were incubated with DMSO (control) or anisomycin (500 ng/ml) for 45 min. The levels of Ser-707 phosphorylation of STAT6 were observed as a mobility shift in Western blots. The arrow indicates a shifted band.

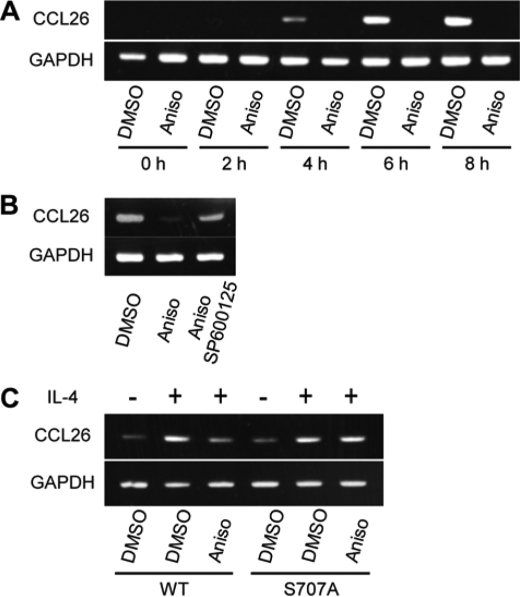

Ser-707 Phosphorylation of STAT6 Negatively Regulates Its Transcriptional Activity

Small molecule inhibitors of PP2A, a Ser/Thr-protein phosphatase, are known to induce multiple serine phosphorylations in the transactivation domain of STAT6, which repress its transcriptional activity (20, 24). Serine phosphorylations in the transactivation domains of STAT1 and STAT3 also regulate their transcriptional activities. Therefore, we hypothesized that Ser-707 phosphorylation of STAT6 similarly regulates the transcriptional activity of STAT6. To test this hypothesis, we compared expression levels of CCL26, a representative STAT6-responsive gene (34), in anisomycin-treated and untreated HeLa cells. Cells were exposed to IL-4 after incubation with anisomycin or DMSO control for 1 h. RT-PCR analysis of extracted mRNA samples revealed a decrease of CCL26 expression in anisomycin-treated cells compared with control cells (Fig. 4A). Similar repression of CCL26 was observed in nocodazole-treated cells (supplemental Fig. S1). Expression levels of CCL26 did not decrease in HeLa cells co-treated with anisomycin and SP600125, a well-known JNK inhibitor (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Repression of IL-4-induced transcriptional activity of STAT6 by Ser-707 phosphorylation. A, effects of anisomycin treatment on IL-4-indcued transcriptional activity of STAT6. HeLa cells were incubated with DMSO or anisomycin (Aniso; 500 ng/ml) for 1 h, and stimulated by IL-4 (10 ng/ml) for 0–8 h. The mRNA levels of CCL26 (upper panel) and GAPDH (lower panel) were quantified by RT-PCR. GAPDH served as a loading control. B, effects of JNK inhibitor on IL-4-indcued transcriptional activity of STAT6 in anisomycin-treated cells. HeLa cells were co-incubated with anisomycin (Aniso; 500 ng/ml) and JNK inhibitor, SP600125 (20 μm), for 1 h, then stimulated by IL-4 (10 ng/ml) for 6 h. The CCL26 levels were quantified by RT-PCR. C, IL-4-induced transcriptional activity of STAT6 in anisomycin-treated cells with WT and S707A mutant STAT6. WT or S707A mutant-expressed HEK293 cells were incubated with anisomycin for 1 h, then stimulated by IL-4 (10 ng/ml) for 6 h. The CCL26 levels were quantified by RT-PCR.

We next tested the hypothesis that overexpression of the S707A mutant of STAT6 would maintain transcriptional activity in anisomycin-treated cells. HEK293 cells, which do not express endogenous functional STAT6, were used in this experiment. Anisomycin had no detectable effects on the expression level of CCL26 in the S707A-overexpressed cells (Fig. 4C), further confirming that Ser-707 phosphorylation by JNK inhibits IL-4-induced gene activation by STAT6.

Ser-707 Phosphorylation Decreases the DNA Binding Activity of STAT6

To determine how phosphorylation of Ser-707 down-regulates STAT6, we first examined the effects of anisomycin on Tyr-641 phosphorylation induced by IL-4. HeLa cells were incubated with anisomycin for 1 h, then stimulated with IL-4 for 30 min. Whole cell lysates were subsequently analyzed by Western blotting, using an anti-pY STAT6 antibody. Anisomycin had no effects on the amount of IL-4-induced tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT6, and the bands of Tyr-641-phosphorylated STAT6 were shifted by anisomycin treatment (Fig. 5A).

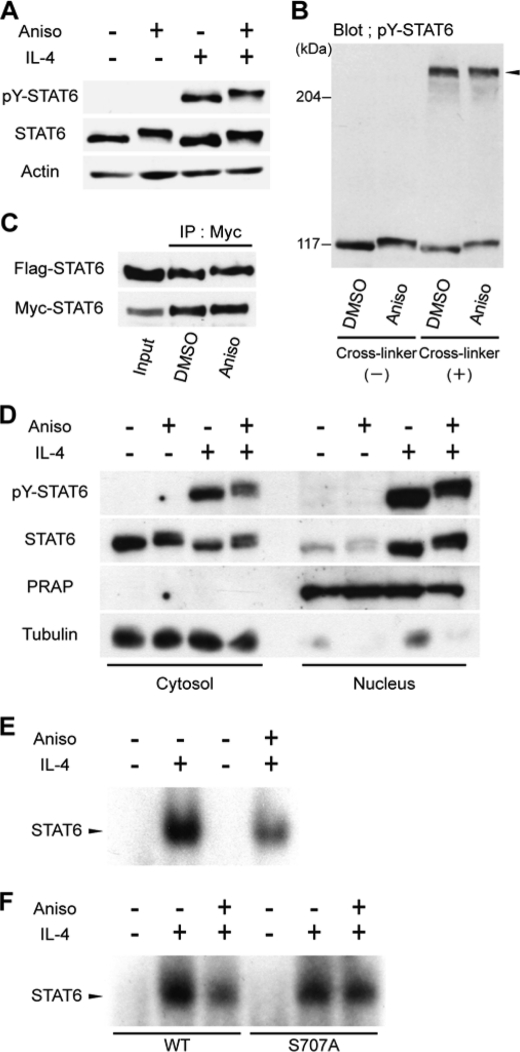

FIGURE 5.

Analysis of repression mechanism for transcriptional activity of Ser-707-phosphorylated STAT6. A, effects of anisomycin treatment on tyrosine phosphorylation levels of STAT6. HeLa cells were incubated with anisomycin (Aniso; 500 ng/ml) for 1 h, then stimulated by IL-4 (10 ng/ml) for 30 min. The whole cell lysates were separated by 5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by Western blotting, using anti-pY STAT6 (upper panel), anti-STAT6 (middle panel), or anti-β-actin antibodies (lower panel). β-Actin served as a loading control. B, effects of anisomycin treatment on dimerization levels of STAT6. Whole cell lysates prepared as described for A were reacted by cross-linking reagent (DSS, 0.5 mm) for 30 min, then the reaction mixtures were analyzed as described for A using anti-pY STAT6 antibody. The arrow shows a band of STAT6 dimer. C, effects of anisomycin treatment on dimerization levels of STAT6. HEK293 cells were transiently co-transfected with expression vectors of Myc-tagged and Flag-tagged STAT6. After 24 h, the cells were incubated with anisomycin (Aniso; 500 ng/ml) for 1 h, and then stimulated by 10 ng/ml IL-4 for 30 min. The cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc-agarose beads. The immunoprecipitated samples and the input sample (1%) were resolved by 5% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-Flag (upper panel) and anti-Myc (lower panel) antibodies. D, effects of anisomycin treatment on nuclear translocation of STAT6. HeLa cells were incubated with anisomycin (Aniso; 500 ng/ml) for 1 h, then stimulated by 10 ng/ml IL-4 for 30 min. The cell lysates were fractionated into nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments. Each compartment was subsequently analyzed by Western blotting, using anti-pY STAT6 (upper panel), anti-STAT6 (upper middle panel), anti-PARP (lower middle panel), or anti-α-tubulin (lower panel) antibodies. PARP and α-tubulin served as nuclear and cytoplasmic controls, respectively. E, effects of anisomycin treatment on DNA binding affinity of endogenous STAT6. HeLa cells were incubated with anisomycin (Aniso; 500 ng/ml) for 1 h, then stimulated by 10 ng/ml IL-4 for 30 min. Twenty micrograms of whole cell lysates, prepared using buffer C, were used for EMAS, with N6-GAS as a probe. F, DAN binding activities of STAT6WT and S707A mutant in the presence of anisomycin. HEK293 cells expressing WT or S707A mutant of STAT6 were incubated with anisomycin (Aniso; 500 ng/ml) for 1 h, and then stimulated by 10 ng/ml IL-4 for 30 min. DNA binding activities were analyzed by EMSA as described in E.

To determine whether Ser-707 phosphorylation induced by anisomycin inhibits IL-4-induced dimerization of STAT6, HeLa cells were treated with anisomycin, and cell lysates were reacted with a cross-linking agent, so that endogenous STAT6 dimers were covalently crosslinked. Western blot analysis using anti-pY STAT6 antibody showed that treatment with anisomycin did not affect the band whose molecular weight matched that of the STAT6 homodimer (Fig. 5B).

We also performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments for the STAT6 homodimer. HEK293 cells were co-transfected with two expression plasmids encoding Flag-tagged STAT6 and Myc-tagged STAT6. The transfected cells were treated with anisomycin for 1 h, then stimulated with IL-4 for 30 min. Myc-tagged STAT6 in the lysates was immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc agarose beads, and the co-immunoprecipitated Flag-tagged STAT6 was analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-Flag antibody. Anisomycin treatment had no detectable impact on the amount of Flag-tagged STAT6 co-immunoprecipitated with Myc-tagged STAT6 (Fig. 5C), consistent with the cross-linking experiments. Therefore, we concluded that Ser-707 phosphorylation of STAT6 has no significant effect on its IL4-induced dimerization.

We next checked the nuclear translocation of STAT6. HeLa cells were incubated with anisomycin for 1 h, and then stimulated with IL-4 for 30 min. The cell lysates were fractionated into nuclear and cytoplasmic components. Each component was subsequently analyzed by Western blotting, using anti-STAT6 and anti-pY STAT6 antibodies. Anisomycin treatment had no detectable effect on the levels of STAT6 and pY-STAT6 in nuclear extracts, indicating that Ser-707 phosphorylation does not affect the IL4-induced nuclear translocation of STAT6 (Fig. 5D).

Finally, electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were performed to analyze the DNA-binding activity of STAT6. HeLa cells were incubated with anisomycin for 1 h, then stimulated with IL-4 for 30 min, and whole cell lysates were prepared. The DNA binding affinity of endogenous STAT6 was analyzed using N6-GAS, an oligonucletide containing a high affinity binding site for STAT6, as a probe (5, 35). The DNA binding activity of STAT6 decreased in anisomycin-treated cells compared with control (DMSO-treated) cells (Fig. 5E), and restored by addition of SP600125, a JNK inhibitor (supplemental Fig. S2A). The decrease of the DNA binding activity of STAT6 was also observed in nocodazole-treated cells (supplemental Fig. S2B).

Similar experiments were conducted with HEK293 cells, which do not express functional endogenous STAT6. HEK293 cells were transfected with an expression vector encoding wild-type STAT6 or its S707A mutant. The DNA binding affinity of wild-type STAT6 decreased upon anisomycin treatment, while the binding affinity of the S707A mutant was not affected (Fig. 5F). Overall, these results suggest that Ser-707 phosphorylation impairs the DNA binding activity of IL4-activated STAT6, resulting in the suppression of STAT6-responsive genes.

IL-1β Stimulation Induces Ser-707 Phosphorylation and Suppresses Transcriptional Activity of STAT6

Ser-707 of STAT6 is directly phosphorylated by JNK, which is activated by a number of endogenous and exogenous factors, including cytokines, ultraviolet irradiation, heat shock, and osmotic shock. Based on the relevance of STAT6 to cytokine signaling, the effects of JNK-activating cytokines on Ser-707 phosphorylation of STAT6 were examined. We first tested the ability of IL-1β, a typical pro-inflammatory cytokine that leads to activation of JNK (36, 37), to induce the STAT6 band shift. Whole cell lysates from HeLa cells stimulated by IL-1β showed the predicted STAT6 mobility shift (Fig. 6A). However, the S707A alanine-substitution mutant of STAT6 failed to show a mobility shift in response to IL-1β treatment (Fig. 6B). These results indicated that IL-1β stimulation induces Ser-707 phosphorylation of STAT6.

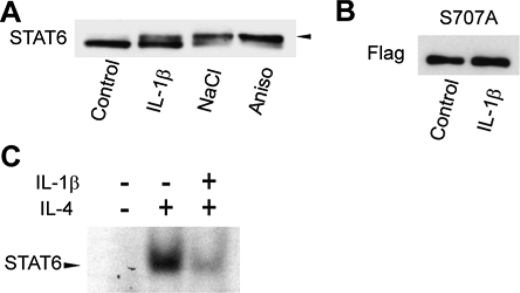

FIGURE 6.

Ser-707 phosphorylation and down-regulation of STAT6 by IL-1β. A, induction of the STAT6 mobility shift by IL-1β treatment. HeLa cells were stimulated by 10 ng/ml IL-1β for 1 h, then the whole cell lysates were separated by 5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-STAT6 antibody. B, induction of STAT6 Ser-707 phosphorylation by IL-1β stimulation. S707A mutant was transiently overexpressed in HeLa cells, which were stimulated by 10 ng/ml IL-1β for 1 h. The whole cell lysates were separated by 5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-Flag antibody. C, effects of IL-1β stimulation on DNA binding affinity of STAT6. HeLa cells were stimulated by 10 ng/ml IL-1β for 1 h, then stimulated by 10 ng/ml IL-4 for 30 min. Twenty micrograms of whole cell lysates, prepared using buffer C, were used for EMSA, with N6-GAS as a probe.

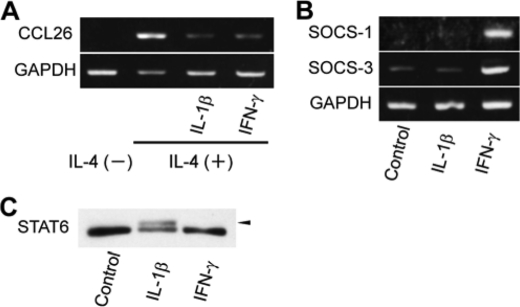

Because Ser-707 phosphorylation of STAT6 represses its transcriptional activity, we examined the effects of IL-1β on the DNA binding affinity of STAT6. Treatment with IL-1β decreased of STAT6-DNA complexes upon IL-4 stimulation by an amount similar to the decrease caused by treatment with anisomycin (Fig. 6C). IL-1β stimulation also repressed the IL-4-induced expression of CCL26, a representative STAT6-responsive gene. HeLa cells were stimulated by IL-1β for 1 h, then by IL-4 for 6 h. RT-PCR analyses of extracted mRNA samples showed that the IL-4-induced expression of CCL26 was reduced by IL-1β to the levels in non-stimulated cells or cells stimulated by interferon-γ (IFN-γ) (Fig. 7A). IFN-γ, a T helper 1 (Th1) cytokine, which plays a critical role in host immune responses, suppresses IL-4-induced STAT6 activation through the induction of expression of suppresser of cytokine signal (SOCS) genes (38, 39). Expression of SOCS-1 and -3 genes in HeLa cells, measured by RT-PCR, was not induced by IL-1β, but was induced by IFN-γ (Fig. 7B). Western blot analysis also showed that IFN-γ stimulation failed to induce Ser-707 phosphorylation of STAT6 in HeLa cells (Fig. 7C). The mechanism by which IL-1β deactivates STAT6 is clearly distinct from that of IFN-γ, and phosphorylation of Ser-707 is likely to mediate the deactivation of STAT6 by IL-1β.

FIGURE 7.

Ser-707 phosphorylation of STAT6 inhibits overlap between IL-1β and IL-4 signals. A, effects of IL-1β and IFN-γ signals on IL-4-induced transcriptional activity of STAT6. HeLa cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml IL-1β or IFN-γ for 1 h, then stimulated by 10 ng/ml IL-4 for 6 h. The mRNA levels of CCL26 (upper panel) and GAPDH (lower panel) were quantified by RT-PCR. B, induction of SOCS-1 and -3 gene expression by stimulation with IL-1β or IFN-γ. HeLa cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml IL-1β or IFN-γ for 6 h, then the mRNA levels of SOCS-1 (upper panel), SOCS-3 (middle panel), and GAPDH (lower panel) were quantified by RT-PCR. GAPDH served as a loading control. C, comparison of Ser-707 phosphorylation levels with IL-1β and IFN-γ stimulation. Whole cell lysates were separated by 5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by Western blotting, using anti-STAT6 antibody.

DISCUSSION

Results of the present study demonstrate that JNK phosphorylates Ser-707 and, thereby, suppresses the IL-4-induced transcriptional activation of STAT6. When cells were treated with either p38 or JNK inhibitors, the Ser-707 phosphorylation of STAT6 was impaired. However, Ser-707 of STAT6 was phosphorylated in vitro only by JNK, and not by p38; and knockdown of p38 had no detectable effects on Ser-707 phosphorylation. Although the p38 inhibitor, SB202190, has been reported to have little inhibitory activities against JNK at the concentration used in the present study, SB202190 did block the Ser-707 phosphorylation in cell-based assays. SB202190 inhibits cyclin G-associated kinase (GAK) and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) at levels similar to p38, and inhibits receptor-interacting protein 2 (RIP2) even more than p38 (40, 41), suggesting that Ser/Thr-protein kinases other than JNK might be involved in the phosphorylation of Ser-707 of STAT6. Indeed, in STAT1 and STAT3, identical serine residues are phosphorylated by a few distinct kinases (21, 22, 42, 43). Further investigations are needed to determine if additional kinases are involved in Ser-707 phosphorylation of STAT6.

Our studies identified a new phosphorylation site, Ser-707, in STAT6, which controls the transcriptional activity of STAT6 upon cell stress or exposure to IL-1β. Although STAT6 possesses five potential phosphorylation sites that match the consensus substrate sequences of JNK, we detected phosphorylation only of Ser-707 in the transactivation domain. Phosphorylation of multiple serine residues at unknown locations in the transactivation domain of STAT6 has been reported in cells treated with calyculin A, a small molecule that inhibits PP2A (22). To determine if calyculin A treatment induces Ser-707 phosphorylation, the S707A mutant of STAT6 was transiently expressed in HeLa cells, and the cells were treated with calyculin A for 45 min. Western blot analyses revealed that calyculin A treatment induced a large shift of the S707A mutant band, similar to the band shift observed in wild-type STAT6 (supplemental Fig. S3), suggesting that the sites of phosphorylation induced by PP2A inhibition are distinct from those induced by Ser-707.

The transactivation domain of STAT6 (amino acids 621–847) is one of a family of proline-rich transactivation domains in a variety of transcription factors, including B cell-specific activator protein (44) and erythroid kruppel-like factor (45), which are proposed to recruit various chromatin remodeling proteins and coactivators. The transactivation domain of STAT6 has been suggested to interact with a number of coactivators, including p100 (46) and NcoA-1 (47). There are numerous examples in which phosphorylation of transactivation domains modulates interactions with coactivators. Therefore, we examined the effects of anisomycin on the protein-protein interaction between STAT6 and one of its co-activators, NcoA-1. Anisomycin treatment had no detectable impact on the amount of NcoA-1 co-immunoprecipitated with Flag-tagged STAT6 (supplemental Fig. S4), suggesting that the inhibition of STAT6 by Ser-707 phosphorylation is not due to decreased interaction with NcoA-1. Indeed, the LXXLL motif, a typical binding site for NcoA-1, is 100 amino acids away from Ser-707.

It remains unknown how phosphorylation in the transactivation domain, which is ∼280 amino acids away from the COOH terminus of the DNA-binding domain in the primary sequence, reduces the DNA binding activity of STAT6. Results of previous investigations indicated that phosphorylation of various transcription factors modulates their DNA binding activities primarily by two mechanisms. First, phosphorylation of residues within or close to the DNA-binding site can directly affect DNA binding (48–51). Second, phosphorylation can lead to a conformational change, resulting in an indirect modulation of DNA-binding activity (52–54). In STAT6, Ser-707 is located away from the DNA-binding domain (amino acids 268–430) in the primary sequence, and therefore, direct inhibition of DNA binding by the negatively charged phosphorous group seems unlikely. The second mechanism, in which phosphorylation of Ser-707 induces a conformational alteration extending to the DNA-binding domain, appears more likely. The peptide segment adjacent to Ser-707 is rich in acidic residues (707Ser-Pro-Glu-Glu-Ser), which upon phosphorylation, might mask the positively charged DNA binding interface of STAT6 through intramolecular interactions.

Inhibition of IL-4 signals by other classes of cytokines, such as IFN-γ, has been well described. This interference is usually mediated by induction of SOCS genes, which bind to the IL-4 receptor or JAK (55). In contrast, our results suggest that IL-1β interferes with IL-4 signals by phosphorylating Ser-707 of STAT6 in HeLa cells without inducing SOCS genes. Ser-707 phosphorylation of STAT6 may be an alternate mechanism for deactivating IL-4 signals by other classes of cytokines.

Our results showed that JNK is one of the kinases that phosphorylate Ser-707 of STAT6. Results of previous studies have suggested a role of JNK in immune responses. The JNK signaling pathway has been implicated to play important roles in the differentiation and activation of T cells (56). Moreover, JNK activation negatively regulates production of Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4 (57, 58). Although further studies are needed for confirmation, the ability of JNK to phosphorylate Ser-707 of STAT6 might be involved in its roles in immune responses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Osada and T. Sudo (Riken) for providing DNA constructs and the members of the Uesugi research group for helpful discussion and support. The Kyoto research group participates in the Global COE program “Integrated Material Sciences” (B-09).

This work was supported in part by grants from JSPS (21310140, to M. U., and 20611007, to Y. K.), the Uehara Memorial Foundation (to M. U.), and the Naito Foundation (to S. S.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4.

- PP2A

- protein phosphatase 2A

- DSS

- disuccinimidyl suberate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Darnell J. E., Jr., Kerr I. M., Stark G. R. (1994) Science 264, 1415–1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Darnell J. E., Jr. (1997) Science 277, 1630–1635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ivashkiv L. B., Hu X. (2004) Arthritis Res. Ther. 6, 159–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ihle J. N. (1996) Cell 84, 331–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hou J., Schindler U., Henzel W. J., Ho T. C., Brasseur M., McKnight S. L. (1994) Science 265, 1701–1706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Akimoto T., Numata F., Tamura M., Takata Y., Higashida N., Takashi T., Takeda K., Akira S. (1998) J. Exp. Med. 187, 1537–1542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kaplan M. H., Schindler U., Smiley S. T., Grusby M. J. (1996) Immunity 4, 313–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Takeda K., Tanaka T., Shi W., Matsumoto M., Minami M., Kashiwamura S., Nakanishi K., Yoshida N., Kishimoto T., Akira S. (1996) Nature 380, 627–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shimoda K., van Deursen J., Sangster M. Y., Sarawar S. R., Carson R. T., Tripp R. A., Chu C., Quelle F. W., Nosaka T., Vignali D. A., Doherty P. C., Grosveld G., Paul W. E., Ihle J. N. (1996) Nature 380, 630–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen Y. R., Wang X., Templeton D., Davis R. J., Tan T. H. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 31929–31936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dérijard B., Hibi M., Wu I. H., Barrett T., Su B., Deng T., Karin M., Davis R. J. (1994) Cell 76, 1025–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marshall S. W., Kawachi I., Cryer P. C., Wright D., Slappendel C., Laird I. (1994) N Z Med J 107, 434–437 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mansour S. J., Matten W. T., Hermann A. S., Candia J. M., Rong S., Fukasawa K., Vande Woude G. F., Ahn N. G. (1994) Science 265, 966–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sluss H. K., Barrett T., Dérijard B., Davis R. J. (1994) Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 8376–8384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wei Y., Pattingre S., Sinha S., Bassik M., Levine B. (2008) Mol Cell 30, 678–688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gupta R. K., Bhatia V., Poptani H., Gujral R. B. (1995) J Pediatr. 126, 389–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Galcheva-Gargova Z., Dérijard B., Wu I. H., Davis R. J. (1994) Science 265, 806–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aguirre V., Uchida T., Yenush L., Davis R., White M. F. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 9047–9054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen C. Y., Del Gatto-Konczak F., Wu Z., Karin M. (1998) Science 280, 1945–1949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yamashita H., Xu J., Erwin R. A., Farrar W. L., Kirken R. A., Rui H. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 30218–30224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wen Z., Zhong Z., Darnell J. E., Jr. (1995) Cell 82, 241–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lim C. P., Cao X. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 31055–31061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morinobu A., Gadina M., Strober W., Visconti R., Fornace A., Montagna C., Feldman G. M., Nishikomori R., O'Shea J. J. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 12281–12286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang Y., Malabarba M. G., Nagy Z. S., Kirken R. A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 25196–25203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Maiti N. R., Sharma P., Harbor P. C., Haque S. J. (2005) J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 25, 553–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Woetmann A., Brockdorff J., Lovato P., Nielsen M., Leick V., Rieneck K., Svejgaard A., Geisler C., Ǿdum N. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 2787–2791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wilkinson K. A., Henley J. M. (2010) Biochem. J. 428, 133–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bode A. M., Dong Z. (2004) Nat. Rev. Cancer 4, 793–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Golks A., Guerini D. (2008) EMBO Rep. 9, 748–753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gu W., Roeder R. G. (1997) Cell 90, 595–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shifrin V. I., Anderson P. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 13985–13992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cano E., Hazzalin C. A., Mahadevan L. C. (1994) Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 7352–7362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yamagishi S., Yamada M., Ishikawa Y., Matsumoto T., Ikeuchi T., Hatanaka H. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 5129–5133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ahn H. J., Kim J. Y., Nam H. W. (2009) Korean J Parasitol 47, 117–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schindler U., Wu P., Rothe M., Brasseur M., McKnight S. L. (1995) Immunity 2, 689–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Uciechowski P., Saklatvala J., von der Ohe J., Resch K., Szamel M., Kracht M. (1996) FEBS Lett. 394, 273–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li X., Commane M., Jiang Z., Stark G. R. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 4461–4465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dickensheets H. L., Venkataraman C., Schindler U., Donnelly R. P. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 10800–10805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Losman J. A., Chen X. P., Hilton D., Rothman P. (1999) J. Immunol. 162, 3770–3774 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Uddin S., Sassano A., Deb D. K., Verma A., Majchrzak B., Rahman A., Malik A. B., Fish E. N., Platanias L. C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 14408–14416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bain J., Plater L., Elliott M., Shpiro N., Hastie C. J., McLauchlan H., Klevernic I., Arthur J. S., Alessi D. R., Cohen P. (2007) Biochem. J. 408, 297–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chung J., Uchida E., Grammer T. C., Blenis J. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 6508–6516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Becker S., Groner B., Müller C. W. (1998) Nature 394, 145–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Anderson K. P., Kern C. B., Crable S. C., Lingrel J. B. (1995) Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 5957–5965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shen C. H., Stavnezer J. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 3395–3404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Välineva T., Yang J., Palovuori R., Silvennoinen O. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 14989–14996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Litterst C. M., Pfitzner E. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 45713–45721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Boyle W. J., Smeal T., Defize L. H., Angel P., Woodgett J. R., Karin M., Hunter T. (1991) Cell 64, 573–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lin A., Frost J., Deng T., Smeal T., al-Alawi N., Kikkawa U., Hunter T., Brenner D., Karin M. (1992) Cell 70, 777–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Caelles C., Hennemann H., Karin M. (1995) Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 6694–6701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Coqueret O., Martin N., Bérubé G., Rabbat M., Litchfield D. W., Nepveu A. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 2561–2566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bullock B. P., Habener J. F. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 3795–3809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cowley D. O., Graves B. J. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 366–376 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yang S. H., Shore P., Willingham N., Lakey J. H., Sharrocks A. D. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 5666–5674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yoshimura A., Naka T., Kubo M. (2007) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 454–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rincón M., Flavell R. A., Davis R. A. (2000) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 28, 1328–1337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dong C., Yang D. D., Tournier C., Whitmarsh A. J., Xu J., Davis R. J., Flavell R. A. (2000) Nature 405, 91–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Dong C., Yang D. D., Wysk M., Whitmarsh A. J., Davis R. J., Flavell R. A. (1998) Science 282, 2092–2095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.