Abstract

Objective

Systemic lupus erythematousus (SLE) is a chronic inflammatory disease associated with aberrant immune cell function. Treatment involves the use of indiscriminate immunosuppression with significant side effects. SLE T cells express high levels of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type IV (CaMKIV) which translocates to the nucleus upon engagement of the T cell receptor (TCR)/CD3 and accounts for abnormal T cell function. We hypothesized that inhibition of CaMKIV should improve disease pathology.

Methods

We treated MRL/lpr mice with KN-93, a CaMKIV inhibitor, starting either at week 8 or week 12 of age through week 16 and evaluated skin lesions, proteinuria, kidney histopathology, pro-inflammatory cytokine production and co-stimulatory molecule expression. We also determined the effect of silencing of CaMKIV on IFN-γ expression by human SLE T cells.

Results

We report that CaMKIV inhibition in MRL/lpr mice results in significant suppression of nephritis, skin disease, decreased expression of the co-stimulatory molecules CD86 and CD80 on B cells and suppression of IFN-γ and TNF-α production. In human SLE T cells, silencing of CaMKIV resulted in suppression of IFN-γ production.

Conclusion

We conclude that suppression of CaMKIV mitigates disease development in lupus-prone mice by suppressing cytokine production and co-stimulatory molecule expression. Specific silencing of CaMKIV in human T cells results in similar suppression of IFN-γ production. Our data justify the development of small molecule CaMKIV inhibitors for the treatment of patients with SLE.

INTRODUCTION

Autoantibodies, immune complexes, cytokines and T lymphocytes contribute to tissue injury in SLE (1, 2) and treatment involves the use of indiscriminate immunosuppressive drugs with significant side effects. T cells from SLE patients have an altered pattern of gene expression that modifies their behavior and grants them increased inflammatory capacity (3). Circulating anti-T cell receptor (TCR)/CD3 complex antibodies present in the sera of SLE patients contribute to the SLE T cell phenotype through a mechanism that involves the activation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type IV (CaMKIV) and its translocation to the nucleus where it affects the expression of genes (4). The pro-inflammatory cytokine IFN-γ (5) and TNF-α (6) have been shown to contribute to the immunopathogenesis of human and murine lupus.

Previous studies examining the role of B cells as autoantigen presenting cells (APCs) in the activation of autoreactive T cells, demonstrated that expression of CD86 and/or CD80 molecules by B cells are essential for breaking T cell tolerance to self antigens (7). CD86 and CD80 expression are increased on the surface membrane of peripheral blood B cells from patients with SLE (8) and may contribute to the increased ability of B cells to provide help to T cells. Moreover, the expression of CD86 and CD80 has been shown to be expressed in the glomeruli of various types of glomerulonephritis and is believed to contribute to tissue pathology (9, 10). Absence of CD86 and/or CD80 co-stimulation interfere with the spontaneous activation and the accumulation of memory CD4+ or CD8+ T lymphocytes in MRL/lpr mice and the development of nephritis, antibody production (11, 12) and skin disease (13).

We hypothesized that inhibition of CaMKIV should interfere with the development of autoimmunity and the expression of disease pathology. Accordingly, we treated MRL/lpr mice with KN-93, a known CaMKIV inhibitor (14–17). We report that CaMKIV inhibition with this small drug inhibitor results in significant suppression of proteinuria, nephritis, IFN-γ and antibody production as well as the expression of CD86 and CD80 on the surface of B cells. In experiments using human SLE T cells, we show that silencing of CaMKIV results in suppression of IFN-γ production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Female MRL/MpJ-Tnfrsf6lpr (MRL/lpr) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. MRL/lpr mice were treated with the CaMKIV inhibitor KN-93 (EMD Bioscience). The agent was administered by intraperitoneal injections at a dose of 0.24 mg/mouse/week of body weight, three times a week. In a disease prevention experiment, KN-93 administration was started before the onset of proteinuria, when the mice were 8 weeks old. These mice received the agent every other week. In a separate experiment, the effectiveness of KN-93 in established disease was evaluated. KN-93 administration was started when mice were 12 weeks old and continued three times a week during 5 weeks. Mice of both experiments were sacrificed at the end of their 16th week of age. All mice were maintained in our SPF animal facility and all experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Urine Analysis

The mice in each group were placed overnight in a Nalgene metabolic cage to collect urine. Urine was measured with Multistix 10SG reagent strips and analyzed by Clinitek Status analyzer (Bayer Healthcare). Proteinuria is expressed as 0–4, 0+ (none), 1+ (30–100 mg/dl), 2+ (100–300 mg/dl), 3+ (300–2000 mg/dl) or 4+ (> 2000 mg/dl) (18, 19).

Histological Analysis

Kidneys and skin were removed, fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections (5μm) were stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin (HE) or Periodic Acid Schiff for light microscopic observation. We evaluated the kidney pathology and quantified the intensity of the disease in glomerular, tubulo-interstitial and perivascular areas according to a previously described scoring system (20, 21).

Measurement of serum anti-dsDNA antibody and cytokines

Serum anti-dsDNA antibody concentration was detected by mouse anti-dsDNA IgG ELISA kit (Alpha Diagnostic). Serum IFN-γ and TNF-α concentrations were detected with ELISA kits (R&D Systems) as per the manufacturer’s protocols.

Measurement of cytokines in cell supernatants

Two million splenocytes were incubated in 1 mL of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS and stimulated with PBS or LPS (1 μg/ml) for 24 hr. At the end of the culture period supernatants were collected. IFN-γ and TNF-α concentrations were detected with ELISA kits (R&D Systems) as per the manufacturer’s protocols.

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions from the spleens of MRL/lpr mice were isolated and stimulated with LPS (1μg/ml) or PBS for 24 hr. Spleen cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated CD80, CD86 (eBioscience) and CD19 (BioLegend) antibodies. Samples were acquired in a LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Analysis was performed with FlowJo v. 7.5.3 (Tree Star). Thirty-thousand T cells were acquired for analysis.

RNA extraction and polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Human T cells from SLE patients and controls were homogenized and total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). cDNA was produced using random primers from an equal amount of RNA. The following primers were designed using Primer3 software (22): IFN-γ forward: 5′-GCAGCCAACCTAAGCAAGAT-3′, IFN-γ reverse: 5′-GGGTCACCTGACACATTCAA-3′, CaMKIV forward: 5′-TGTACACATGGATACCGCTC-3′, CaMKIV reverse: 5′-TCTTCAGCTTCTCCTCTGCT-3′, 18s rRNA forward: 5′-ACTCAACACGGGAAACCTCA-3′, 18s rRNA reverse: 5′-AACCAGACAAATCGCTCCAC-3′.

siRNA transfection

T cells were purified from peripheral blood of patients with SLE and age- and sex-matched controls using Rosettesep (Stem Cell Technologies). T cells were electroporated in the presence of CaMKIV siRNA (Qiagen) or control siRNA using an Amaxa nucleofector (Lonza). After 48 hr of incubation, cells were stimulated with PBS or plate-bound anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies (CD3: 2 μg/ml, CD28: 2μg/ml). After 5 hr culture supernatants were collected and cells were lysed for RNA extraction. IFN-γ concentration was detected with ELISA kit (R&D Systems) as per the manufacturer’s protocols.

Human SLE T cells

T cells were obtained from the peripheral blood of patients with SLE or matched controls as described previously under an Institutional Review Board-approved protocol and transfected with CaMKIV siRNA or control siRNA as described previously (4).

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as mean + SD. Kruskal-Wallis test with post-hoc comparisons using the Scheffe’s test were employed for inter-group comparisons of multiple variables. Statistical analyses were performed by StatView software (Abacus Concepts). A level of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Inhibition of CaMKIV activity blocks disease development in MRL/lpr mice

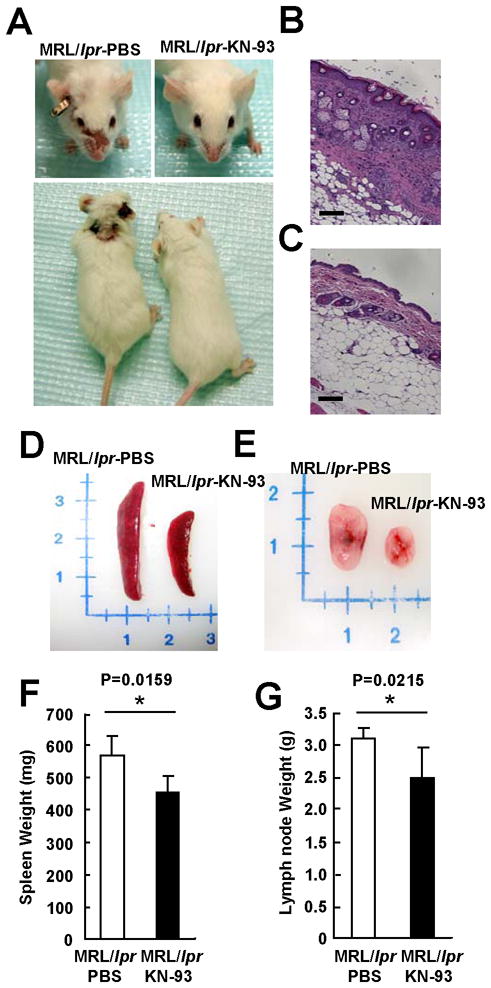

In order to determine if CaMKIV plays a role in the pathogenesis of lupus in the MRL/lpr model, we treated 8-week-old mice with KN-93, a pharmacological CaMKIV inhibitor. As shown in Figure 1, KN-93 administration prevented the appearance of skin lesions (Figure 1A and B) and reduced significantly the size and weight of spleens (Figure 1D and F) and lymph nodes (Figure 1E and G). The well-known expanded double negative T cell population (CD3+CD4−CD8−) in the spleens of MRL/lpr mice decreased significantly after treatment with KN93, whereas the CD8+ cell subset increased (Suppl Fig. 1). Similarly, the percentage of CD62Llow (activated T cells) decreased significantly (not shown). Further, serum titers of anti-double stranded DNA antibodies decreased significantly in mice treated with KN-93 (P<0.01) (Figure 2E). These results indicate that CaMKIV contributes to the increased lymphocyte activation that causes skin disease and spleen and lymph node enlargement in the MRL/lpr mouse (Figure 4E).

Figure 1. Treatment of MRL/lpr mice with the CaMKIV inhibitor KN-93 ameliorates disease expression in MRL/lpr mice.

(A) Facial and body skin lesions of MRL/lpr mice treated with PBS or KN-93 starting at week 8 of age. Representative skin sections stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin (HE), (B) MRL/lpr mice treated with PBS, (C) MRL/lpr mice treated with KN-93. Bar equals to 100 μm. Representative spleen (D) and lymph nodes (E) from MRL/lpr mice treated with PBS or KN-93 starting at week 8 of age. Spleen (F) and lymph node (G) weight of MRL/lpr mice treated with KN-93 starting at week 8 of age presented (*p<0.05; n≥6 mice per group).

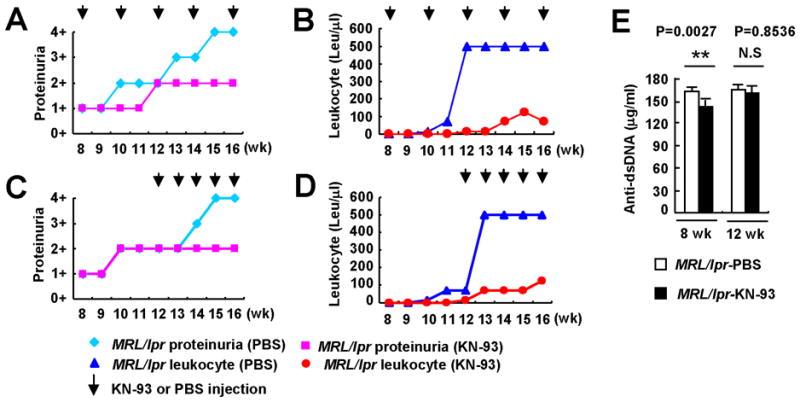

Figure 2. Treatment of MRL/lpr mice with the CaMKIV inhibitor KN-93 ameliorates lupus nephritis.

(A, Urinary protein B, Leukocytes) Pre-disease, 8-week-old MRL/lpr mice were treated with either KN-93 or PBS. The agent was administered intraperitoneally three times a week (0.24 mg/mouse/week), every other week, for 8 weeks. Measurements were performed weekly during the treatment period. The arrows indicate administration of treatment. (C, Urinary protein; D Leukocytes) Diseased, 12-week-old MRL/lpr mice were treated with KN-93 or PBS. Treatment was administered three times a week (0.24 mg/mouse/week), for 5 weeks and measurements were performed weekly (n≥5 mice per group). (E) Anti-dsDNA IgG antibodies were detected by ELISA (**p<0.01; n≥6 mice per group). Kruskal-Wallis test was used for statistical analyses. Results are expressed as mean + SD.

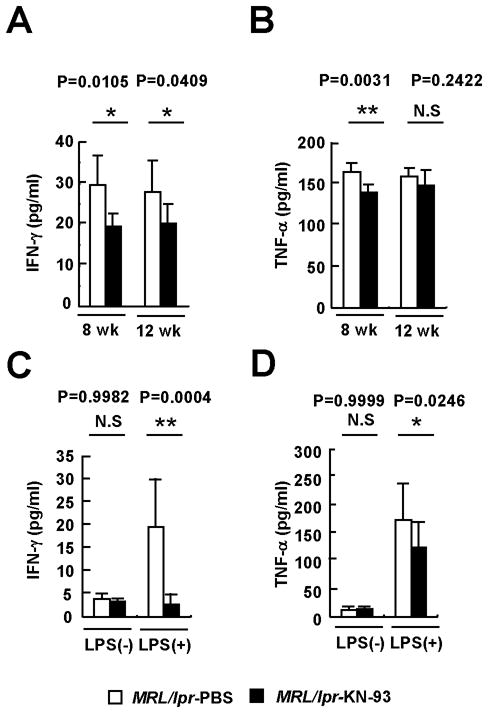

Figure 4. KN-93 suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokine production in MRL/lpr mice.

(A) IFN-γ and (B) TNF-α levels were quantified in sera from MRL/lpr mice treated with PBS or KN-93 from the 8th or 12th week of age (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; n≥6 mice per group). (C) IFN-γ and (D) TNF-α levels in supernatants from splenocytes incubated with PBS or LPS (1 μg/ml) for 24 hr in the presence or absence of KN-93 (10 μM) (*p< 0.05; **p<0.01; n≥6 16-week-old mice per group). (E) Anti-dsDNA IgG antibodies were detected by ELISA (**p<0.01; n≥6 mice per group). Kruskal-Wallis test was used for statistical analyses. Results are expressed as mean + SD.

MRL/lpr mice develop an immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis manifested by proteinuria and pyuria

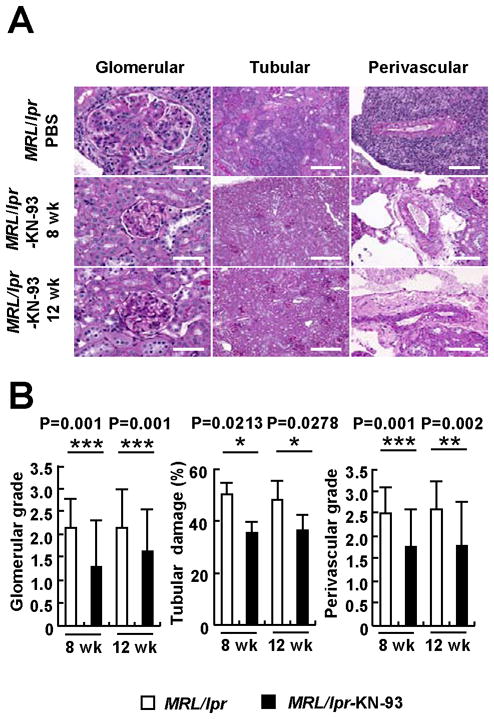

As shown in Figure 2, these signs of renal inflammation were prevented by the administration of KN-93. Accordingly, inhibition of CaMKIV decreased significantly the degree of kidney damage assessed by histological analysis (Figure 3). Mice treated with KN-93 developed significantly less damage in glomerular, tubule-interstitial, and perivascular areas than mice treated with PBS. Importantly, these results were observed when preventive KN-93 administration was started in 8-week-old mice (before the onset of disease) and also when disease onset preceded the instauration of treatment (Figure 2 and 3).

Figure 3. Treatment of MRL/lpr mice with the CaMKIV inhibitor KN-93 ameliorates lupus nephritis.

(A) Representative images of glomerular, tubulo-interstitial and perivascular areas from 16-week-old MRL/lpr mice treated with PBS (upper panels, stained with Periodic Acid Schiff) and KN-93.. The photographs in the middle panels correspond to mice treated before the onset of proteinuria (8-week-old); the lower panels to mice treated after the disease had been established (12-week-old). Bar equals to 50μm (glomerular), 200μm (tubular) and 100μm (perivascular). (B) Mean scores of glomerular injury, tubular damage and perivascular lymphocyte infiltration (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p=0.001; n≥6 mice per group). Kruskal-Wallis test was used for the statistical analyses.

Inhibition of CaMKIV reduces pro-inflammatory cytokine production and expression of co-stimulatory molecules

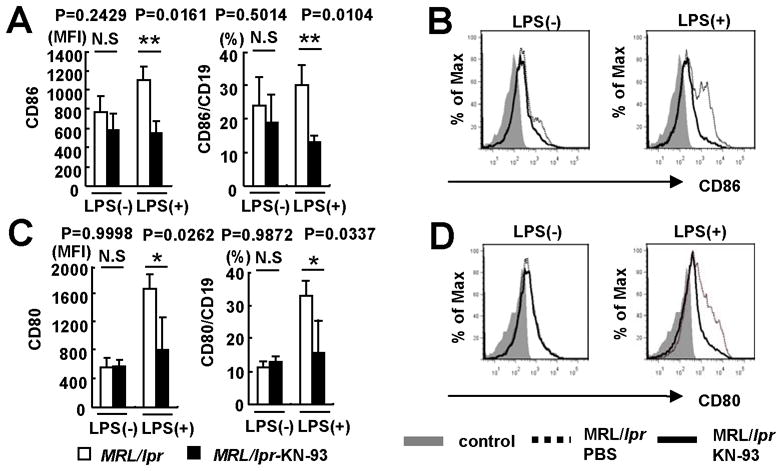

To define the mechanism through which KN-93 prevents disease in MRL/lpr mice, we analyzed the production of two essential inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ and TNF-α). As shown in Figure 4, KN-93 treatment caused a significant reduction in the serum levels of these mediators. Ex vivo stimulation of spleen cells isolated from MRL/lpr mice confirmed the fact that KN-93 is able to block LPS-induced production of IFN-γ and to reduce significantly the secretion of TNF-α. Inhibition of CaMKIV in spleen cells also diminished the activation of B cells in response to LPS and decreased their capacity to stimulate T lymphocytes by abolishing the up-regulation of the co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 (Figure 5). Taken together, these data indicate that CaMKIV is a key element in the inflammatory response that drives autoimmunity in the MRL/lpr mice.

Figure 5. KN-93 decreases CD86 and CD80 expression on spleen B cells from MRL/lpr mice.

Splenocytes were isolated from MRL/lpr mice and stimulated with LPS (1μg/ml) or PBS for 24hr. Cumulative data of flow cytometry for (A) CD86 and (C) CD80 expression gated for CD19+ cells. MFI; mean fluorescence intensity. Kruskal-Wallis test was used for statistical analyses. Results are expressed as mean + SD (*p<0.05; **p=0.01; n=3 24-week-old mice per group). Representative histograms comparing (B) CD86 and (D) CD80 expression gated for CD19+ cells. Splenocytes were treated with KN-93 (10μM) (solid line) or PBS (dotted line) for 24hr. Shaded area represents isotype control staining.

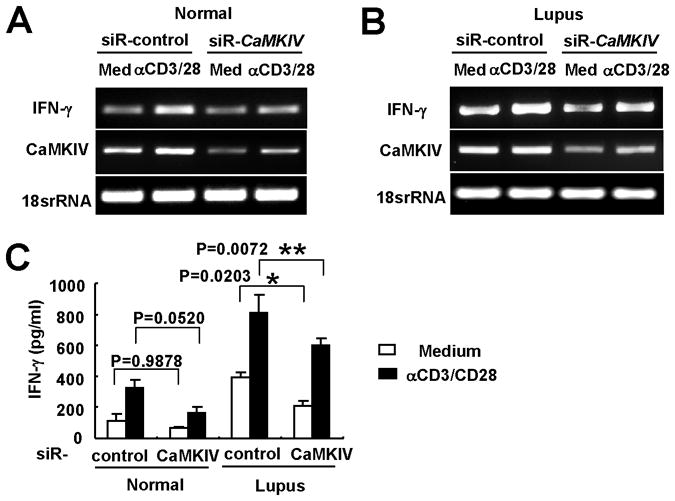

CaMKIV is involved in the production of IFN-γ in T cells from patients with SLE

To determine the relevance of our findings in human disease, we analyzed the effect of CaMKIV inhibition in T cells obtained from patients with SLE and healthy individuals. Production of IFN-γ was higher in cells from patients with SLE than in normal controls (Figure 6). Transfection with specific siRNA was able to knockdown the expression of CaMKIV in T cells (Figure 6A and B); this inhibition caused a significant decrease in the production of IFN-γ in cells from patients with SLE. This indicates that the CaMKIV is involved in the expression of IFN-γ in patients with SLE.

Figure 6. CaMKIV siRNA suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokine production by human T cells.

T cells from a healthy control (left panel) and a patient with SLE (right panel) were transfected with either control siRNA or CaMKIV-specific siRNA. After 48 hr cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 5 hr. IFN-γ mRNA and CaMKIV mRNA of T cells from a healthy control (A) and a patient with SLE (B) were quantified by RT-PCR. 18srRNA was used as loading control. 1 of 4 similar experiments is shown. (C) IFN-γ levels in supernatants from human T cells (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; n=4).

DISCUSSION

In the present study we demonstrate that CaMKIV inhibition results in significant suppression of proteinuria, glomerulonephritis, IFN-γ and antibody production and decreased expression of the co-stimulatory molecules CD86 and CD80. The experiments herein were designed after we had shown that SLE T cells express high levels of CaMKIV which translocates to the nucleus upon engagement of the TCR/CD3 (4) in order to demonstrate the in vivo significance of the CaMKIV overexpression in the development of SLE. The successful treatment of MRL/lpr mice with the CaMKIV inhibitor KN-93, prior to and after the initiation of the disease, suggests that CaMKIV contributes to the expression of autoimmunity and organ damage through mechanisms unrelated to thymic selection.

Several effector immune cell mechanisms are known to contribute to the pathogenesis of murine and human lupus (3). IFN-γ has been demonstrated to be important in the expression of disease in the MRL/lpr mouse and disruption of its production suppresses or eliminates the expression of the disease (23). Here we show that inhibition of CaMKIV in the MRL/lpr mouse and silencing CaMKIV in human lupus T cells significantly suppresses the expression of IFN-γ (Figures 4 and 6).

It has been reported that lymphoid hyperplasia in MRL/lpr mice represents the expansion of double negative (DN) T cells, which may derive, both in mice (24, 25) and humans (26) from activated CD8 T cells. We evaluated whether KN-93 can influence CD4, CD8, DN T cells and B cells populations in MRL/lpr mice. In our studies we observed that while the CD8+ population increased, the DN subset decreased significantly in the spleens of MRL/lpr treated with KN93 (Supplemental figure 1).

In human SLE, CD86 and CD80 expression on resting and activated B cells is increased compared to cells from normal individuals (8, 27). In the lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice upregulation of CD86 and CD80 expression has been reported (12, 13) and demonstrated to be important in the expression of the disease. Moreover, blockade of the engagement of CD86 and CD80 with CTLA4-Ig in NZB/NZW F1 mice prevented the development of a lupus-related disease. This treatment blocked autoantibody production and prolonged survival, even when it was delayed until the advanced stages of the disease (28). Our studies demonstrate that pharmacologic inhibition of CaMKIV, using ex vivo B cells from MRL/lpr mice (Figure 5), resulted in decreased expression of CD86 and CD80 expression.

KN-93 probably has global suppressive effects on the immune system which extend beyond those of T cells of MRL/lpr mice. Herein we show that costimulatory molecule expression by B cells is decreased (Figure. 5) along with the production of TNFα by spleen macrophages (Figure. 4). In addition, we have found that IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α production by human monocytes/macrophages is suppressed in the presence of KN93 (not shown).

Although KN-93 has been claimed to inhibit CaMKIV, it has been reported to inhibit CaMKI and CaMKII as well (14–17). It is possible that some of the observed effects may be due to the inhibition of several CaMKs. Although, SLE T cells express increased amounts of CaMKIV and not other CaMKs (4), we used a CaMKIV-specific silencing approach to reproduce one of the claimed mechanisms of action, the IFN-γ production. The fact that silencing CaMKIV suppresses IFN-γ production by human T cells supports our claim that CaMKIV inhibition is important in the mitigation of lupus pathology and these claims are transferable to humans.

In conclusion, we have provided evidence that increased IFN-γ, TNF-α and autoantibody production as well as increased expression of CD86 and CD80 represent pathways through which increased level of CaMKIV may lead to autoimmunity and to relevant pathology. We have presented in vivo and in vitro evidences that KN-93, or another, more specific CaMKIV inhibitor may deserve to be further developed for the treatment of patients with SLE. We show that KN-93 not only prevents, but it also suppresses established disease in MRL/lpr mice. The agreement between our human and murine data further strengthens this claim. Since CaMKIV is expressed in neuronal cells also and it is important for the proper function of these cells, like in case of any other drug, timing and dosing will determine its therapeutic efficacy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by PHS NIH Grant RO1 AI 49954.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT INFORMATION

The work presented herein was exclusively supported by NIH funds. None of the authors have received or expect to receive royalties from industry as a result of this work. None of the authors has potential financial conflicts that could compromise the claims made here in.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Drs. Ichinose, Juang and Tsokos had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study design: Kunihiro Ichinose, Yuang-Taung Juang, George C. Tsokos

Acquisition of data: Kunihiro Ichinose, Yuang-Taung Juang, Jose Crispin, Katalin Kis-Toth

Analysis and interpretation of data: Kunihiro Ichinose, Yuang-Taung Juang, Jose Crispin, Katalin Kis-Toth, George Tsokos

Manuscript preparation: Kunihiro Ichinose, George C. Tsokos

Statistical analysis: Kunihiro Ichinose

References

- 1.Mayadas TN, Tsokos GC, Tsuboi N. Mechanisms of immune complex-mediated neutrophil recruitment and tissue injury. Circulation. 2009;120(20):2012–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.771170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davidson A, Aranow C. Lupus nephritis: lessons from murine models. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6(1):13–20. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crispin JC, Liossis SN, Kis-Toth K, Lieberman LA, Kyttaris VC, Juang YT, et al. Pathogenesis of human systemic lupus erythematosus: recent advances. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16(2):47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juang YT, Wang Y, Solomou EE, Li Y, Mawrin C, Tenbrock K, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus serum IgG increases CREM binding to the IL-2 promoter and suppresses IL-2 production through CaMKIV. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(4):996–1005. doi: 10.1172/JCI200522854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baccala R, Kono DH, Theofilopoulos AN. Interferons as pathogenic effectors in autoimmunity. Immunol Rev. 2005;204:9–26. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacob CO. Studies on the role of tumor necrosis factor in murine and human autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 1992;5 (Suppl A):133–43. doi: 10.1016/0896-8411(92)90028-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roth R, Nakamura T, Mamula MJ. B7 costimulation and autoantigen specificity enable B cells to activate autoreactive T cells. J Immunol. 1996;157(7):2924–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolff S, Wilde B, Patschan S, Durig J, Specker C, Philipp T, et al. Peripheral circulating activated b-cell populations are associated with nephritis and disease activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Scand J Immunol. 2007;66(5):584–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.02008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Q, Jinde K, Endoh M, Sakai H. Costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 in human crescentic glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41(5):950–61. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Odobasic D, Kitching AR, Semple TJ, Timoshanko JR, Tipping PG, Holdsworth SR. Glomerular expression of CD80 and CD86 is required for leukocyte accumulation and injury in crescentic glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(7):2012–22. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004060437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang B, Gee RJ, Kashgarian MJ, Sharpe AH, Mamula MJ. B7 costimulation in the development of lupus: autoimmunity arises either in the absence of B7.1/B7.2 or in the presence of anti-b7.1/B7.2 blocking antibodies. J Immunol. 1999;163(4):2322–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang B, Kashgarian MJ, Sharpe AH, Mamula MJ. Autoantibody responses and pathology regulated by B7-1 and B7-2 costimulation in MRL/lpr lupus. J Immunol. 2000;165(6):3436–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kinoshita K, Tesch G, Schwarting A, Maron R, Sharpe AH, Kelley VR. Costimulation by B7-1 and B7-2 is required for autoimmune disease in MRL-Faslpr mice. J Immunol. 2000;164(11):6046–56. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.6046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, Wheeler D, Tang Y, Guo L, Shapiro RA, Ribar TJ, et al. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) IV mediates nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and release of HMGB1 during lipopolysaccharide stimulation of macrophages. J Immunol. 2008;181(7):5015–23. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.5015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsung A, Klune JR, Zhang X, Jeyabalan G, Cao Z, Peng X, et al. HMGB1 release induced by liver ischemia involves Toll-like receptor 4 dependent reactive oxygen species production and calcium-mediated signaling. J Exp Med. 2007;204(12):2913–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sato K, Suematsu A, Nakashima T, Takemoto-Kimura S, Aoki K, Morishita Y, et al. Regulation of osteoclast differentiation and function by the CaMK-CREB pathway. Nat Med. 2006;12(12):1410–6. doi: 10.1038/nm1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Illario M, Giardino-Torchia ML, Sankar U, Ribar TJ, Galgani M, Vitiello L, et al. Calmodulin-dependent kinase IV links Toll-like receptor 4 signaling with survival pathway of activated dendritic cells. Blood. 2008;111(2):723–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-091173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng GM, Tsokos GC. Cholera toxin B accelerates disease progression in lupus-prone mice by promoting lipid raft aggregation. J Immunol. 2008;181(6):4019–26. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng GM, Liu L, Bahjat R, Pine PR, Tsokos GC. Inhibition of spleen tyrosine kinase suppresses skin and kidney disease in lupus prone mice. Arthritis Rheum. doi: 10.1002/art.27452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kikawada E, Lenda DM, Kelley VR. IL-12 deficiency in MRL-Fas(lpr) mice delays nephritis and intrarenal IFN-gamma expression, and diminishes systemic pathology. J Immunol. 2003;170(7):3915–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sadanaga A, Nakashima H, Akahoshi M, Masutani K, Miyake K, Igawa T, et al. Protection against autoimmune nephritis in MyD88-deficient MRL/lpr mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(5):1618–28. doi: 10.1002/art.22571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rozen S, Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;132:365–86. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balomenos D, Rumold R, Theofilopoulos AN. Interferon-gamma is required for lupus-like disease and lymphoaccumulation in MRL-lpr mice. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(2):364–71. doi: 10.1172/JCI750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balomenos D, Rumold R, Theofilopoulos AN. The proliferative in vivo activities of lpr double-negative T cells and the primary role of p59fyn in their activation and expansion. J Immunol. 1997;159(5):2265–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Budd RC, Mixter PF. The origin of CD4−CD8−TCR alpha beta+ thymocytes: a model based on T-cell receptor avidity. Immunol Today. 1995;16(9):428–31. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crispin JC, Oukka M, Bayliss G, Cohen RA, Van Beek CA, Stillman IE, et al. Expanded double negative T cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus produce IL-17 and infiltrate the kidneys. J Immunol. 2008;181(12):8761–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Folzenlogen D, Hofer MF, Leung DY, Freed JH, Newell MK. Analysis of CD80 and CD86 expression on peripheral blood B lymphocytes reveals increased expression of CD86 in lupus patients. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;83(3):199–204. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finck BK, Linsley PS, Wofsy D. Treatment of murine lupus with CTLA4Ig. Science. 1994;265(5176):1225–7. doi: 10.1126/science.7520604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.