Abstract

Bryostatin 1 is a marine natural product that is a very promising lead compound due to the potent biological activity it displays against a variety of human disease states. We describe herein the first total synthesis of this agent. The synthetic route adopted is a highly convergent one in which preformed and heavily functionalized pyran rings A and C are united by “pyran annulation”: the TMSOTf promoted reaction between a hydroxy allylsilane appended to the A ring fragment and an aldehyde contained in the C ring fragment, with concomitant formation of the B ring. Further elaborations of the resulting very highly functionalized intermediate include macrolactonization and selective cleavage of just one of five ester linkages present.

Bryostatin 1 is a now well-known natural product originally isolated by Pettit and coworkers from the marine organism Bugula neritina.1 Since that time, other members of this family have been isolated such that some 20 members are now known.2 It has also been established that the true source of the bryostatins is not actually Bugula neritina, but rather a bacterial symbiont.3

Interest in the bryostatins, and bryostatin 1 in particular, has been intense due to the wide range of potent bioactivity associated with bryostatin 1. Bryostatin 1 has shown activity against a range of cancers, and has also shown synergism with established oncolytic agents such as Taxol®.4 This has led to the use of bryostatin 1 in numerous clinical trials for cancer, despite the absence of any renewable supply for this compound at present. In addition, bryostatin 1 has shown promising activity relevant to a number of other diseases and conditions, including diabetes,5 stroke,6 and Alzheimer's disease.7 A clinical trial for Alzheimer's disease is commencing.8 This wide range of promising potential indications for bryostatin 1 becomes more understandable when it is recognized that at least one mechanism for function of this agent involves activity on protein kinase C (PKC) isozymes and on other C1 domain containing proteins.9 These signaling proteins are known to regulate some of the most critical cellular processes and properties, including proliferation, differentiation, motility and adhesion, inflammation, and apoptosis.10

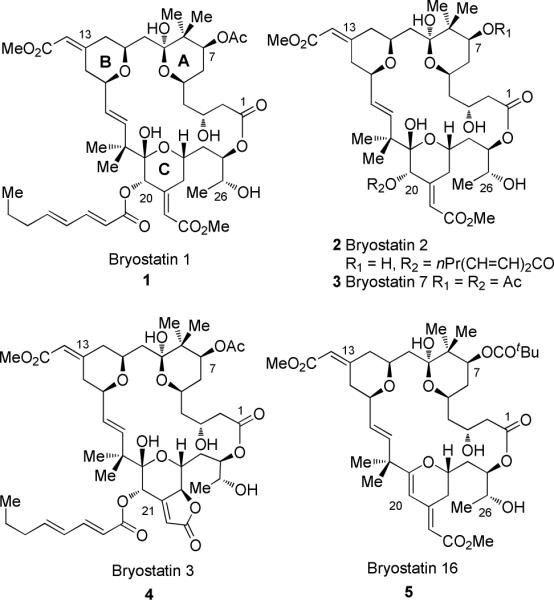

Given this backdrop, it is not surprising that synthetic activity directed towards the bryostatins has been intense. What is surprising, perhaps, is that bryostatin 1 itself has not been previously synthesized, while other members of the family have been prepared. Previous total syntheses include those of bryostatin 7 (2, by Masamune), bryostatin 2 (3, by Evans), bryostatin 3 (4, by Yamamura), and bryostatin 16 (5, by Trost). In addition, Hale has described a formal synthesis of bryostatin 7, and Trost has recently reported a synthesis of C20-epi-bryostatin 7.11

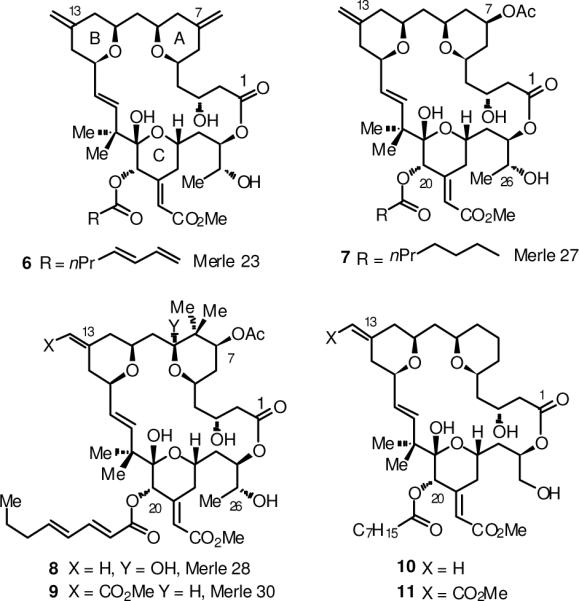

Another very important aspect of bryostatin synthesis has been the area of analogue synthesis, originally introduced by Wender and coworkers.12 This group targeted analogues in which the B-ring pyran was replaced by an acetal linkage for ease of synthesis. Recent work in our laboratory directed at establishing structure activity relationships for bryostatin 1 has led to the synthesis of a number of bryopyrans which are close structural analogues of the bryostatin natural products, using methodology developed explicitly for this purpose.13 The pyran annulation process has been used to prepare the analogues Merle 23 (6) and Merle 27 (7),14 which display phorbol ester-like biology in U937 leukemia cells, as well as analogues Merle 28 (8) and Merle 30 (9), which are predominantly bryo-like in the same differential assay.15 In addition, Wender has prepared the bryopyran analogues 10 and 11 using the intramolecular variant of the pyran annulation reaction, as well as numerous other analogues incorporating the previously mentioned scaffold variation in which the B-ring pyran is replaced by an acetal.16

The work directed at Merle 23 and 27, when compared to that directed towards Merle 28 and 30, afforded an opportunity to compare two convergent strategies for the union of A-ring and C-ring fragments with concomitant formation of the B-ring. Based on this previous experience, a strategy of A-ring hydroxy allylsilane plus C-ring aldehyde was selected for an attempted synthesis of bryostatin 1.

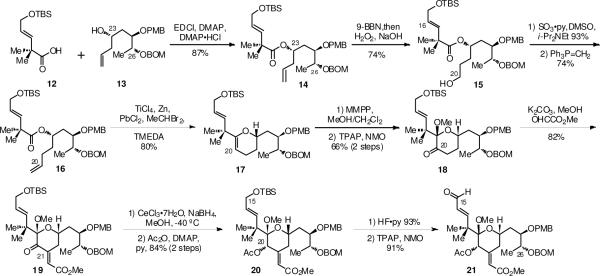

The synthesis of the fully functionalized C-ring fragment used a new approach which was more convergent than that utilized previously for the Merle analogues. Carboxylic acid 12 (available in 4 steps) was esterified with the previously reported homoallylic alcohol 13 (prepared from commercial R-isobutyl lactate in 6 steps).13b Selective oxidative functionalization at the terminus of the less hindered alkene followed by Wittig chain extension afforded 16, which was then utilized in a Rainier metathesis reaction to construct glycal 17 in 80% yield.17 Oxidative functionalization of the glycal afforded methoxy ketone 18 in 66% yield over two steps. Aldol condensation with methyl glyoxylate then afforded the enoate 19 in 82% isolated yield.18 Luche reduction gave an intermediate C20 alcohol which was found to be unstable with respect to purification by column chromatography or to storage. Immediate acetylation of the alcohol after isolation gave the C20 acetate derivative 20 in 84% yield for the two steps of reduction and acylation. This was converted to aldehyde 21 in 91% yield by TBS removal and Ley oxidation using TPAP and NMO.

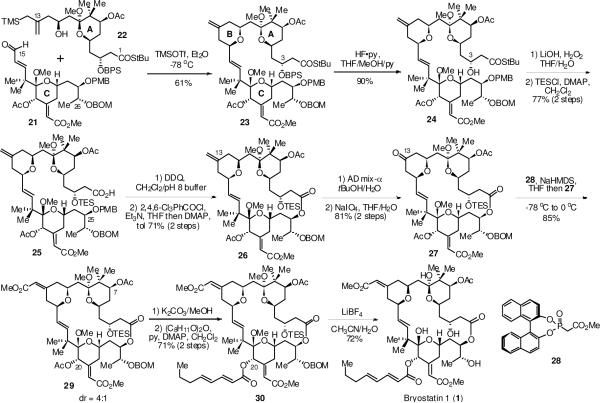

The A ring hydroxy allylsilane 22 was prepared in three steps via an allylation of the corresponding and previously reported aldehyde.19 The crucial pyran annulation reaction between the A ring hydroxy allylsilane 22 and the C ring aldehyde 21 then provided the tricyclic intermediate 23 in 61% isolated yield. This represents one of the most complex examples of such a pyran annulation to date. The major byproduct was a spirocylic structure formed via an intramolecular cyclization of the silane onto the C9 position of 22. However, attempts to suppress this side reaction by increasing the number of equivalents of the aldehyde or increasing the concentration of the reaction were not successful.

Hydrolysis of the thiolester to reveal the carboxylic acid was attempted next. Selective hydrolysis using various reagents such as LiOH/H2O2, AgNO3/H2O, or Hg(OCOCF3)2 was complicated due to the competitive hydrolysis of other esters, hydrolysis of the methyl ketals, or oxymercuration of the olefins. After considerable experimentation, it was discovered that this hydrolysis could be carried out selectively using LiOH/H2O2 if the C3 hydroxyl was free. The exact origin of the selectivity is unclear but a decrease in the steric hindrance around the thiolester and activation of the C1 carbonyl due to hydrogen bonding with the C3 alcohol seems to be the most reasonable explanation. To obtain the free alcohol, the BPS group was removed using HF·py under buffered conditions. The presence of methanol during the silyl deprotection was necessary to avoid any hydrolysis of the methyl ketals at C19 and particularly C9. Treatment of the β-hydroxy thiolester with LiOH/H2O2 in aqueous THF then cleanly afforded the β-hydroxy carboxylic acid. Since the free hydroxyl group at the C3 position was found to interfere with the subsequent macrolactonization, it was protected as the TES ether. Following removal of the PMB group using DDQ, the resulting seco acid was subjected to Yamaguchi macrolactonization conditions20 which gave the macrolactone 26 in 71% yield over the two steps.

At this point, the regioselective oxidative cleavage of the C13–C30 olefin could be achieved on 26 by either ozonolysis or by reaction with OsO4/NaIO4. However a protocol involving Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation followed by periodate oxidation was found superior to other conditions and provided ketone 27 in 81% yield.21 An asymmetric Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons reaction on the ketone using Fuji's chiral BINOL phosphonate 28 provided a 4:1 mixture of Z:E α,β-unsaturated methyl esters in favor of the desired isomer.22 The geometric isomers were easily separated using preparative thin layer silica gel chromatography.

When the bisacetate 29 was subjected to exposure to K2CO3/MeOH, we were pleased to find that selective methanolysis of the C20 acetate occurred in just 45 min providing the desired C20 alcohol. The regioselectivity observed in this reaction could be best explained by activation of the C20 acetate due to the inductive effects associated with the neighboring groups. Since the C20 alcohol was again found to be unstable, it was immediately esterified by reaction with (2E,4E)-octa-2,4-dienoic anhydride to give a protected version of bryostatin 1 in 71% yield from bis-acetate 29. When this protected bryostatin 1 derivative 30 was subjected to global deprotection using LiBF4 in acetonitrile/water at 80 °C,23 two methyl ketals, the TES ether and the BOM group were all removed, without cleavage of any of the five esters present, providing bryostatin 1 in 72% yield. It should be noted that a similar deprotection of the bisacetate 29 would provide bryostatin 7. In addition, it is apparent that introduction of other side chains at the C20 position as described above would lead to the synthesis of other naturally occurring bryostatins such as bryostatins 9 and 15, as well as new bryostatin analogues.

The analytical data for synthetic bryostatin 1 were found to be in excellent agreement with those of a sample of natural bryostatin 1 by several criteria such as TLC, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, 13C DEPT, high resolution mass spectroscopy, optical rotation, and LC/MS. As previously reported in the literature and observed by us, the 1H NMR spectra of the bryostatins are highly concentration dependent and very sensitive to trace water or D2O.24 A change of just twofold in concentration gave observable changes in the proton NMR spectra. Thus the richly detailed 13C NMR spectra (all carbons observed) of synthetic and natural samples serve as a more reliable fingerprint.

In summary, the total synthesis of bryostatin 1 has been achieved by convergent union of the A-ring hydroxy allylsilane 22 with the C ring aldehyde 21. An almost perfect balance in convergence was realized as 21 was prepared in 18 steps while 22 was made in 17 steps. After union of these two fragments an additional 11 steps afforded bryostatin 1. This first total synthesis of bryostatin 1 was thus accomplished in 30 steps for the longest linear sequence, from commercially available R-isobutyl lactate.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Bryostatin structures.

Figure 2.

Representative bryopyran analogues.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of C ring aldehyde 21 using the Rainier metathesis reaction.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of bryostatin 1 via pyran annulation.

Acknowledgment

Financial support of this research by the National Institutes of Health through Grant GM-28961 is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Dr. Peter Blumberg of the NCI for supplying an authentic sample of bryostatin 1 for comparison purposes.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Experimental procedures and spectral data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).Pettit GR, Herald CL, Doubek DL, Herald DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:6846–6848. [Google Scholar]

- (2).For reviews of the bryostatins and bryostatin analogues, see:Hale KJ, Hummersome MG, Manaviazar S, Frigerio M. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2002;19:413–453. doi: 10.1039/b009211h.. Hale KJ, Manaviazar S. Chem. Asian J. 2010;5:704–754. doi: 10.1002/asia.200900634..

- (3).Sudek S, Lopanik NB, Waggoner LE, Hildebrand M, Anderson C, Liu H, Patel A, Sherman DH, Haygood MG. J. Nat. Prod. 2007;70:67–74. doi: 10.1021/np060361d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Schwartz GK, Shah MA. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:9408–9421. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.5594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang S, Wang Z, Dent P, Grant S. Blood. 2003;101:3648–3657. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Way KJ, Katai N, King GL. DiabeticMed. 2001;18:945–959. doi: 10.1046/j.0742-3071.2001.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Sun M-K, Hongpaisan J, Nelson TJ, Alkon DL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., U.S.A. 2008;105:13620–13625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805952105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Etcheberrigaray R, Tan M, Dewachter I, Kuiperi C, Vander Au, Wera I, Wera S, Qiao L, Bank B, Nelson TJ, Kozikowski AP, Van Leuven F, Alkon DL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., U.S.A. 2004;101:11141–11146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403921101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Alkon DL, Sun M-K, Nelson TJ. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2007;28:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).For further information see: http://www.brni.org.

- (9).Dell'Aquilla ML, Harold CL, Kamano Y, Pettit GR, Blumberg PM. Cancer Res. 1988;48:3702–3708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).(a) Reyland ME, Insel PA, Messing RO, Dempsey EC, Newton AC, Mochly-Rosen D, Fields AP. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2000;279:429–438. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.3.L429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Griner EM, Kazanietz MG. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:281–294. doi: 10.1038/nrc2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Roffey J, Rosse C, Linch M, Hibbert A, McDonald NQ, Parker PJ. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2009;21:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).(a) Kageyama M, Tamura T, Nantz MH, Roberts JC, Somfai P, Whritenour DC, Masamune S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:7407–7408. [Google Scholar]; (b) Evans DA, Carter PH, Carreira EM, Charette AB, Prunet JA, Lautens M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:7540–7552. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ohmori K, Ogawa Y, Obitsu T, Ishikawa Y, Nishiyama S, Yamamura S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000;39:2290–2294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Manaviazar S, Frigerio M, Bhatia GS, Hummersone MG, Aliev AE, Hale KJ. Org. Lett. 2006;8:4477–4480. doi: 10.1021/ol061626i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Trost BM, Dong G. Nature. 2008;456:485–488. doi: 10.1038/nature07543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Trost BM, Dong G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:16403–16416. doi: 10.1021/ja105129p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) For other synthetic work directed towards the bryostatins, see reference 2.

- (12).Wender PA, DeBrabander J, Harran PG, Jimenez J-M, Koehler MFT, Lippa B, Park C-M, Shiozaki M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:4534–4535. [Google Scholar]

- (13).(a) Keck GE, Covel JA, Schiff T, Yu T. Org. Lett. 2002;4:1189–1192. doi: 10.1021/ol025645d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Keck GE, Truong AP. Org. Lett. 2005;7:2149–2152. doi: 10.1021/ol050511w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Keck GE, Truong AP. Org. Lett. 2005;7:2153–2156. doi: 10.1021/ol050512o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).(a) Keck GE, Kraft MB, Truong AP, Li W, Sanchez CC, Kedei N, Lewin N, Blumberg PM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:6660–6661. doi: 10.1021/ja8022169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Keck GE, Li W, Kraft MB, Kedei N, Lewin NE, Blumberg PM. Org. Lett. 2009;11:2277–2280. doi: 10.1021/ol900585t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).(a) Keck GE, Poudel YB, Welch DS, Kraft MB, Truong AP, Stephens JC, Kedei N, Lewin NE, Blumberg PM. Org. Lett. 2009;11:593–596. doi: 10.1021/ol8027253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) eck GE, Poudel YB, Rudra A, Stephens JC, Kedei N, Lewin NE, Peach ML, Blumberg PM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:4580–4584. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Wender PA, DeChristopher BA, Schrier AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:6658–6659. doi: 10.1021/ja8015632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For an overview of bryostatin analogue synthesis by the Wender group, see: Wender PA, Baryza JL, Hilinski MK, Horan JC, Kan C, Verma VA. Beyond Natural Products: Synthetic Analogues of Bryostatin 1. In: Huang Z, editor. Drug Discovery Research: New Frontiers in the Post-Genomic Era. Wiley-VCH; Hoboken, NJ: 2007. pp. 127–162..

- (17).Iyer K, Rainier JD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12604–12605. doi: 10.1021/ja073880r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Similar aldols have been used previously by Evans (ref 11b), by Wender (ref 16b) and by us (ref 14 and 15). The yield in the present instance is noteworthy, however.

- (19).Keck GE, Welch DS, Poudel YB. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:8267–8270. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.09.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Inanaga J, Hirata K, Saeki H, Katsuki T, Yamaguchi M. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1979;52:1989–1993. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Sharpless KB, Amberg W, Bennani YL, Crispino GA, Hartung J, Jeong KS, Kwong HL, Morikawa K, Wang ZM. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:2768–2771. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Tanaka K, Ohta Y, Fuji K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:4071–4074. [Google Scholar]; (b) For the previous use of the reagent in bryostatin synthesis, see ref 11b.

- (23).Lipschutz BH, Harvey DF. Synth. Commun. 1982;14:267–277. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Chmurny GN, Koleck MP. Mag. Res. Chem. 1991;29:366–374. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.