Abstract

Retroviruses must integrate their cDNA to a host chromosome, but a significant fraction of retroviral cDNA is degraded before integration. XPB and XPD are part of the TFIIH complex which mediates basal transcription and DNA nucleotide excision repair. Retroviral infection increases when XPB or XPD are mutant. Here we show inhibition of mRNA or protein synthesis does not affect HIV cDNA accumulation suggesting that TFIIH transcription activity is not required for degradation. Other host factors implicated in the stability of cDNA are not components of the XPB and XPD degradation pathway. Although an increase of retroviral cDNA in XPB or XPD mutant cells correlates with an increase of integrated provirus, the integration efficiency of pre-integration complexes is unaffected. Finally, HIV and MMLV cDNA degradation appears to coincide with nuclear import. These results suggest that TFIIH mediated cDNA degradation is a nuclear host defense against retroviral infection.

INTRODUCTION

All retroviruses reverse transcribe a genomic RNA to a linear cDNA molecule (Coffin, Hughes, and Varmus, 1997). The cDNA is part of a pre-integration complex (PIC) which includes at least the viral proteins reverse transcriptase, matrix, and integrase (Miller, Farnet, and Bushman, 1997). The retroviral PIC integrates the cDNA into a host chromosome to continue the viral life cycle. Retroviruses, including Molony murine leukemia virus (MMLV), require cellular division and breakdown of the nuclear envelope for the PIC to enter the nucleus. Lentiviruses, such as HIV, do not require cellular division and can traverse an intact nuclear envelope. Previous studies have shown that most of the cDNA that completes reverse transcription will be degraded before integration (Barbosa et al., 1994; Brussel and Sonigo, 2003; Butler, Johnson, and Bushman, 2002; Van Maele et al., 2003; Vandegraaff et al., 2001).

Several host proteins have been shown to inhibit viral replication before integration (Goff, 2004). Most notably, APOBEC3G deaminates cytosines during reverse transcription (Harris et al., 2003; Mangeat et al., 2003). APOBEC3G has also been shown to reduce the accumulation of cDNA, but this finding is controversial (Bishop, Holmes, and Malim, 2006). The proteasome has been shown to play a role in cDNA stability (Butler, Johnson, and Bushman, 2002; Schwartz et al., 1998). In the presence of proteasome inhibitors more retroviral cDNA accumulates. Similarly, mutations of the host XPB (ERCC3) and XPD (ERCC2) proteins correlate with an increase of retroviral cDNA (Yoder et al., 2006). The kinetics of cDNA accumulation is affected by the rate of reverse transcriptase synthesis and the rate of degradation. Degradation of cDNA may be analyzed by abrogating synthesis with the non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor efavirenz. Treatment of XPB or XPD mutant cells with efavirenz following infection resulted in a significantly slower decrease of HIV cDNA compared to wild type cells, suggesting that these proteins participate in a cDNA degradation pathway (Yoder et al., 2006).

XPB and XPD are part of TFIIH, a ten-subunit complex that participates in both basal transcription and DNA nucleotide excision repair (NER; (Giglia-Mari et al., 2004; Ranish et al., 2004). During transcription TFIIH unwinds promoter DNA allowing RNA polymerase access to the DNA template. TFIIH participates in NER by unwinding the DNA helix at the site of DNA damage. XPB and XPD are ATPase helicases with opposing polarity. XPB 3'→5' helicase activity is required for transcription while XPD 5'→3' helicase activity is required for NER (Coin, Oksenych, and Egly, 2007). The XPB ATPase activity is also required for NER, possibly acting as a wrench to initialize separating the DNA helix (Fan et al., 2006). Three diseases are associated with mutations of XPB or XPD: xeroderma pigmentosum (XP), XP with Cockayne Syndrome (XP/CS), and trichothiodystrophy (TTD) (Lehmann, 2001). XP patients are prone to skin cancer due to an inability to complete NER. The XP associated mutation XPB(F99S) reduces interaction of XPB with TFIIH subunit p52, which stimulates XPB ATPase activity at sites of DNA damage (Coin, Oksenych, and Egly, 2007). The XP associated mutation XPD(R683W) affects interaction of XPD with p44 and helicase activity (Dubaele et al., 2003). Hence it is possible to identify and isolate cell lines from XP patients with mutations of XPB or XPD that affect NER. However, deletion of any TFIIH complex gene is lethal due to its essential role in transcription (Friedberg and Meira, 2006).

Previous studies have shown that XPB and XPD mediated degradation of retroviral cDNA is associated with NER activity, but did not directly address the transcription activity of these proteins during cDNA degradation (Yoder et al., 2006). Here we show that XPB and XPD mediated cDNA degradation is not due to altered transcription or translation of other host factors. This degradation pathway is distinct from APOBEC3G or proteasome host defense pathways. While degradation of cDNA leads to less integrated provirus in vivo, the integration efficiency in vitro of PICs isolated from XPB or XPD mutant cells is similar to PICs from wild type cells. Finally, studies of cells arrested by aphidicolin indicate that TFIIH mediated cDNA degradation coincides with entry to the nucleus.

RESULTS

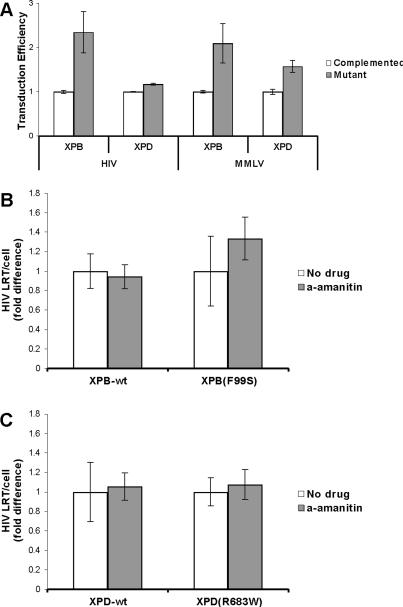

XPB and XPD do not affect cDNA accumulation by transcription

Cell lines were derived from XP patients expressing the XPB(F99S) mutation or the XPD(R683W) mutation (Gozukara et al., 1994; Riou et al., 1999). These cell lines were complemented with the respective wild type gene to generate isogenic cell lines XPB-wt and XPD-wt (Gozukara et al., 1994; Riou et al., 1999). XPB(F99S) and XPD(R683W) cell lines are more sensitive to UV irradiation compared to the complemented cell lines, indicating defective NER (Yoder et al., 2006). Previous studies have shown that retroviral infection, both HIV and MMLV, is more than 100% greater in XPB(F99S) cell lines compared to cells expressing the wild type gene; XPD(R683W) cells have 15% greater retroviral infection efficiency compared to cells expressing wild type XPD (Yoder et al., 2006). The XP cell lines were infected with HIV or MMLV vector particles expressing GFP following successful integration. The cells were analyzed for GFP expression by flow cytometry (Fig. 1A). XPB(F99S) cells showed greater than 100% increase in HIV or MMLV transduction efficiency compared to XPB-wt cells (HIV P=0.0063, MMLV P=0.022). XPD(R683W) cells also display an increase in HIV or MMLV transduction efficiency (HIV P=0.0003, MMLV P=0.0005).

Fig. 1.

Retroviral infection of wild type and NER mutant cell lines. (A) An equal number of NER mutant (XPB(F99S) and XPD(R683W)) and complemented cells (XPB-wt and XPD-wt) were infected with HIV or MMLV retroviral vectors expressing GFP following integration to the host genome. At 72 hpi the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for GFP expression. Transduction efficiency is expressed relative to the complemented cells expressing the wild type gene. (B and C) HIV late reverse transcripts in wild type and NER mutant cells treated with the transcription inhibitor α-amanitin. An equal number of wild type and NER defective cells were treated with the RNA polymerase II inhibitor α-amanitin for 2 hours and infected with an HIV based retroviral vector in the continued presence of α-amanitin (a-amanitin). DNA was collected at 6 hours after the addition of HIV. HIV late reverse transcripts (LRT) and the cellular 18S gene were measured by qPCR. The quantity of HIV LRT was divided by the number of cellular genomes to obtain the number of HIV LRT per cell (HIV LRT/cell). (B) XPB-wt and NER defective XPB(F99S) cell lines. (C) XPD-wt and NER defective XPD(R683W) cell lines. Data from α-amanitin treated cells is expressed relative to untreated cells (No drug). Error bars indicate the standard deviation between triplicates at two MOI in three independent experiments.

The role of XPB and XPD in basal transcription suggests the possibility that shortly following viral entry to the cell, new host factors are transcribed that could be responsible for the observed host defense against retroviral cDNA. To determine whether the TFIIH proteins are transcribing nascent host factors that mediate cDNA degradation, XPB-wt and XPB(F99S) cells were treated with the transcription inhibitor α-amanitin for 2 hours (Fig. 1B). In the continued presence of α-amanitin, cells were infected with an HIV based retroviral vector encoding GFP (Follenzi et al., 2000). These vector particles have previously been shown to faithfully recapitulate the HIV life cycle from reverse transcription through integration (Butler, Johnson, and Bushman, 2002). DNA was collected at 6 hours post infection (hpi), a time point previously shown to display significant differences in cDNA accumulation between mutant and wild type cells (Yoder et al., 2006). The DNA samples were analyzed for HIV late reverse transcripts (LRT) by quantitative PCR (qPCR). The LRT qPCR primer set spans the primer binding site and amplifies all forms of full length HIV cDNA including linear unintegrated cDNA, 1LTR circles, 2LTR circles, and integrated provirus (Butler, Hansen, and Bushman, 2001). In both the presence and absence of α-amanitin, the NER mutant cell line XPB(F99S) showed greater accumulation of cDNA than XPB-wt cells (P < 0.0001 with or without α-amanitin, data not shown). If XPB mediates cDNA degradation through transcription of new host factors, then treatment with α-amanitin will prevent the appearance of nascent defense factors and cDNA accumulation will increase. However, there was no significant difference (XPB-wt P=0.54, XPB(F99S) P=0.19) in cDNA accumulation between untreated cells and cells treated with α-amanitin, suggesting that the transcription activity of TFIIH does not affect retroviral cDNA stability (Fig. 1B). This data is similar to previous reports which found no difference in retroviral infection efficiency between cells expressing XPB-wt and a TTD mutation, XPB(T119P), which has no effect on NER activity (Coin, Oksenych, and Egly, 2007; Yoder et al., 2006). XPD-wt and XPD(R683W) cells were also infected in the presence of α-amanitin and showed no significant difference (XPD-wt P=0.56, XPD(R683W) P=0.13) in the accumulation of HIV cDNA at 6 hpi (Fig. 1C). These results indicate that TFIIH transcription activity is not involved in the degradation of retroviral cDNA.

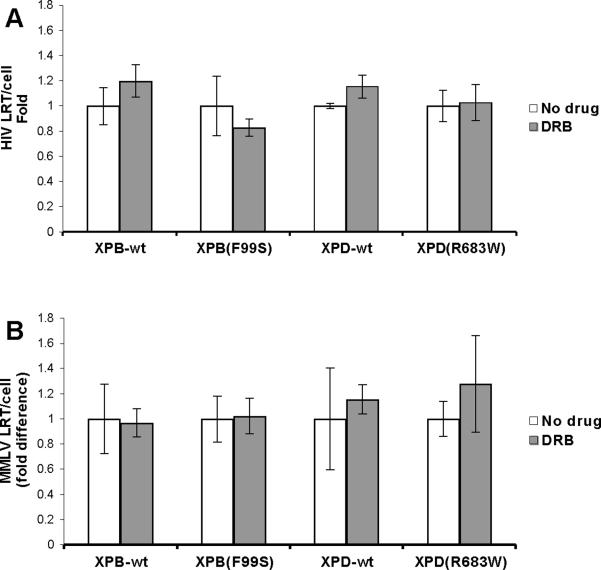

During transcription, the CDK-activating kinase (CAK) subunit of TFIIH exhibits kinase activity necessary for elongation of a nascent mRNA transcript (Roy et al., 1994). The drug DRB inhibits the CAK kinase (Yankulov et al., 1995). DRB was added to the XP cell lines for two hours prior to the addition of HIV and continued for the first 6 hpi to assess the role of TFIIH kinase activity on cDNA degradation. DRB has previously been shown to reduce HIV replication by inhibiting Tat mediated transcription of the integrated HIV provirus (Biglione et al., 2007; Critchfield et al., 1997). In contrast, this experiment measures HIV cDNA well before integration of the provirus. Cells were analyzed for HIV late reverse transcripts by qPCR (Fig. 2A). There was no significant difference in HIV cDNA per cell in any of the XP cell lines when DRB was present (XPB-wt P=0.066, XPB(F99S) P=0.092, XPD-wt P=0.055, XPD(R683W) P=0.69). Similarly, cells were treated with DRB and infected with and MMLV based retroviral vector (Fig. 2B). As with HIV, there was no significant difference in MMLV LRT per cell in any cell line when DRB was present (XPB-wt P=0.76, XPB(F99S) P=0.10, XPD-wt P=0.24, XPD(R683W) P=0.14). The presence of DRB during the first 6 hours of retroviral infection appears to have no significant effects on cDNA stability, suggesting that the CAK kinase activity and TFIIH dependent mRNA transcription elongation do not participate in cDNA degradation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

HIV late reverse transcripts in XP cell lines treated with a CAK inhibitor. Wild type and NER mutant cells were treated with the CAK inhibitor DRB for 2 hours and infected with an HIV based retroviral vector in the continued presence of the drug. DNA was collected at 6 hours after the addition of HIV. HIV late reverse transcripts (LRT) and the cellular 18S gene were measured by qPCR and used to determine HIV LRT per cell. (A) XPB-wt and NER defective XPB(F99S) cell lines. (B) XPD-wt and NER defective XPD(R683W) cell lines. Data from DRB treated cells is expressed relative to untreated cells (No drug). Error bars indicate the standard deviation between triplicates at two MOI in three independent experiments.

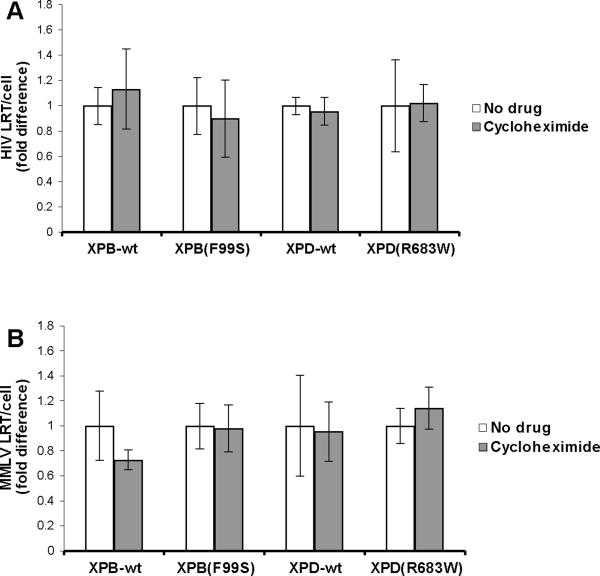

Cycloheximide inhibits the translation of mRNA to protein by the ribosome. This drug was added to XPB-wt, XPB(F99S), XPD-wt, and XPD(R683W) cells for 2 hours. The cells were then infected with HIV in the continued presence of cycloheximide. DNA was collected at 6 hpi and analyzed by qPCR for late reverse transcripts (Fig. 3A). There was no significant difference in HIV cDNA between cells in the presence or absence of cycloheximide (XPB-wt P=0.14, XPB(F99S) P=0.042, XPD-wt P=0.49, XPD(R683W) P=0.91). These results suggest that nascent protein synthesis is not required for cDNA degradation in any of the XP cell lines. Similarly, cells were infected with MMLV in the presence of cycloheximide and cDNA was quantified at 6 hpi (Fig. 3B). There was no significant difference in MMLV cDNA accumulation when cycloheximide was present for any of the XP cell lines (XPB-wt P=0.061, XPB(F99S) P=0.89, XPD-wt P=0.075, XPD(R683W) P=0.11). Taken as a whole, these results suggest that the transcription activity of TFIIH is not involved in the retroviral cDNA degradation pathway.

Fig. 3.

HIV late reverse transcripts in wild type and NER mutant XP cell lines treated with the translation inhibitor cycloheximide. An equal number of (A) XPB-wt and XPB(F99S) or (B) XPD-wt and XPD(R683W) cells were treated with the ribosome inhibitor cycloheximide for 2 hours and infected with an HIV based retroviral vector in the continued presence of cycloheximide. DNA was collected at 6 hours after the addition of HIV particles. HIV late reverse transcripts (LRT) and the cellular 18S gene were measured by qPCR. The quantity of HIV LRT was divided by the number of cellular genomes to obtain the number of HIV LRT per cell (HIV LRT/cell). Data from cycloheximide treated cells is expressed relative to untreated cells (No drug). Error bars indicate the standard deviation between triplicates at two MOI in three independent experiments.

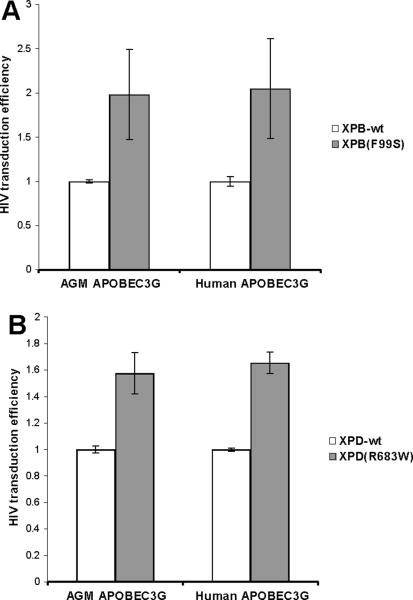

XPB and XPD mediated cDNA degradation is distinct from other retroviral cDNA stability pathways

The host protein APOBEC3G deaminates cytosines in retroviral cDNA during reverse transcription (Harris et al., 2003). Studies have also suggested that APOBEC3G affects the accumulation of full-length reverse transcripts, although this observation is controversial (reviewed in (Albin and Harris, 2010). The HIV Vif protein is able to target human APOBEC3G, but not African green monkey (AGM) APOBEC3G, to the proteasome for degradation (Mariani et al., 2003). Thus, HIV particles generated in the presence of AGM APOBEC3G show significantly reduced infectivity compared to virus generated in the presence of human APOBEC3G. HIV based retroviral vector particles, including the Vif protein, were produced in the presence of either human APOBEC3G or AGM APOBEC3G. XPB(F99S) and XPB-wt cells were infected with these vector particles (Fig. 4). Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for GFP expression and the percentage of positive cells is expressed relative to XPB-wt cells. Infection efficiency in the presence of AGM APOBEC3G was consistently 5 fold lower than human APOBEC3G (data not shown). XPB(F99S) cells displayed greater infection efficiency than XPB-wt cells, confirming previous reports (Fig. 4A, (Yoder et al., 2006). The difference of infection efficiency between XPB(F99S) and XPB-wt cells was similar in the presence of either human or AGM APOBEC3G (Fig. 4A). In the presence of AGM APOBEC3G, infection efficiency of XPB(F99S) cells was 98% greater than XPB-wt; in the presence of human APOBEC3G, the infection efficiency of XPB(F99S) was 104% greater than XPB-wt. A similar pattern was observed for XPD(R683W) and matched wild type cells (Fig. 4B) These results suggest that the difference in infection efficiency between XPB or XPD mutant cells compared to their matched wild type cells was not affected by the presence of AGM APOBEC3G or human APOBEC3G. XPB and XPD appear to act on retroviral cDNA in a pathway that is distinct from APOBEC3G.

Fig. 4.

Role of TFIIH in the APOBEC3G host defense pathway. HIV vector particles including Vif were generated in the presence of African green monkey (AGM) or human APOBEC3G. (A) XPB-wt and XPB(F99S) or (B) XPD-wt and XPD(R683W) cells were infected with AGM or human APOBEC3G HIV vectors. The HIV vector expresses GFP following integration. Cells were assayed by flow cytometry for GFP expression from the integrated HIV cDNA. The infection efficiency of mutant cell lines is expressed relative to wild type cells and % difference graphed. Error bars indicate the standard deviation between duplicates at two MOI in two independent experiments.

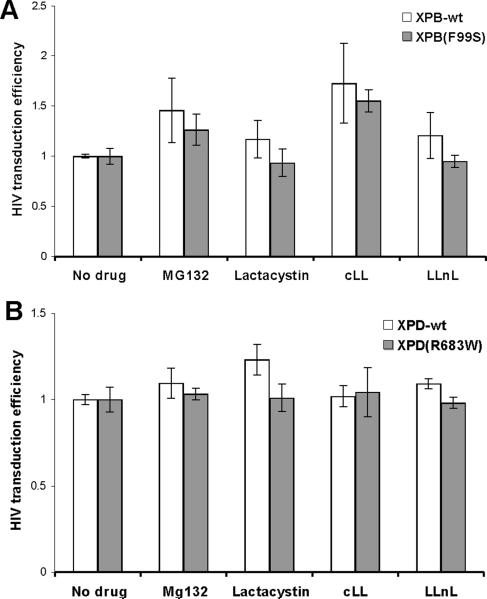

Previous studies with proteasome inhibitors led to an increase in cDNA stability and integration through an unknown mechanism (Butler, Johnson, and Bushman, 2002; Schwartz et al., 1998). NER defective XPB(F99S) cells and XPB-wt cells were treated with the highest tolerable doses of proteasome inhibitors MG132, lactacystin, and clasto-lactacystin β-lactone or a different protease inhibitor, calpain inhibitor I (Fig. 5A). In the continued presence of drug, cells were infected with HIV expressing GFP following integration. The cells were evaluated by flow cytometry for GFP expression at 72 hpi; data is shown relative to infection efficiency in the absence of drug. The addition of proteasome inhibitors slightly increased HIV infection efficiency but only significantly in the presence of clasto-lactacystin β-lactone (no drug vs. clasto-lactacystin β-lactone: XPB-wt P=0.0016, XPB(F99S) P=0.01; Fig. 5A). There was no significant difference between matched XPB NER mutant and wild type cells (Fig. 5A, MG132 P=0.11, lactacystin P=0.20, clasto-lactacystin β-lactone P=0.15). An inhibitor that does not target the proteasome, calpain inhibitor I, also did not display a significant difference between XPB mutant and wild type cells (calpain inhibitor I P=0.14). Similar results were observed with the NER mutant XPD(R683W) and XPD-wt cell lines (Fig. 5B, MG132 P=0.40, lactacystin P=0.075, clasto-lactacystin β-lactone P=0.63). This data suggests that the proteasome effects on cDNA accumulation appear to be unrelated to XPB/XPD mediated cDNA degradation.

Fig. 5.

Effects of proteasome inhibitors on HIV infection efficiency in XP cell lines. (A) XPB-wt and XPB(F99S) cells were infected with HIV vector particles in the presence of 2 μM MG132, 2 μM lactacystin, 2 μM clasto-lactacystin β-lactone (cLL), or 5 μM calpain inhibitor I (LLnL). (B) XPD-wt and XPD(R683W) cells were infected with HIV vector particles in the presence of 0.5 μM MG132, 2.5 μM lactacystin, 1 μM clasto-lactacystin β-lactone (cLL), or 50 μM calpain inhibitor I (LLnL). The HIV vector particles express GFP following integration and cells were assayed by flow cytometry for GFP expression 72hpi. Infection efficiency is expressed relative to cells infected in the presence of DMSO (No drug). Error bars indicate the standard deviation between duplicates at two MOI in three independent experiments.

XPB and XPD do not affect PIC-mediated integration in vitro

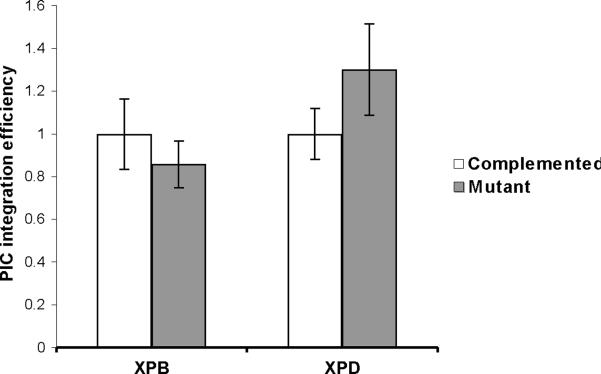

Our previous studies showed that integration efficiency increases in the presence of NER mutant XPB or XPD (Yoder et al., 2006). Change of integration efficiency could be due to direct effects of XPB/XPD proteins on the enzymatic activity of the integration complex or wild type XPB/XPD may simply reduce the number of full length cDNAs available for integration. The effects of XPB and XPD on integrase catalytic activity were evaluated with pre-integration complexes (PICs, Fig. 6). PICs were isolated from infected cells 6 hours after HIV particles were added to the cells. An exogenous target DNA was added to the PICs allowing integration in vitro (Farnet and Haseltine, 1990). The integration efficiency of PICs was calculated as the number of integrated proviruses divided by the total number of complete late reverse transcripts measured by qPCR. PICs were prepared from XPB(F99S), XPB-wt, XPD(R683W), and XPD-wt cells (Fig. 6). Genomic DNA from uninfected 293T cells was added to the PICs as an exogenous DNA target. Integration efficiency was measured by qPCR and is expressed relative to PICs from wild type cells. We found no significant differences in the integration efficiency between PICs prepared from matched NER mutant and wild type cells (Fig. 6, XPB P=0.053, XPD P=0.14). These results suggest that XPB and XPD are unlikely to directly affect the integration reaction.

Fig. 6.

Integration efficiency of PICs derived from XP cell lines. XPB-wt (complemented), XPB(F99S), XPD-wt (complemented), and XPD(R683W) cell lines were infected with HIV vector particles. PIC extracts were harvested at 6 hpi. 100 ng human genomic DNA was added to PICs as an integration target and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. DNA was purified and assayed by qPCR for late reverse transcripts and integration products. The PIC integration efficiency is expressed relative to PICs from wild type complemented cells. Error bars indicate the standard deviation between duplicate integration reactions from two independent preparations of PICs.

Degradation of retroviral cDNA coincides with entry to the nucleus

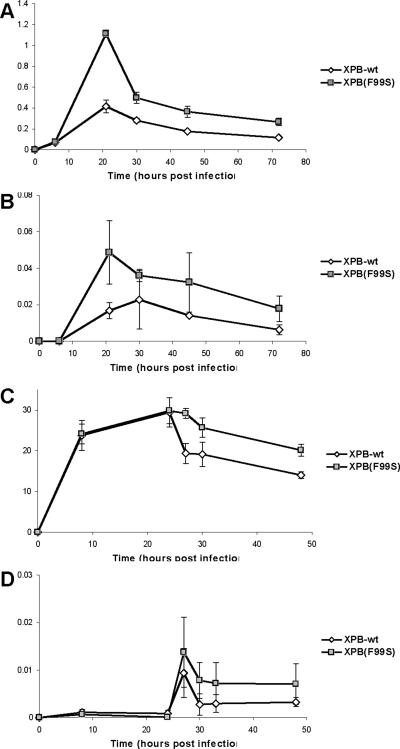

XPB and XPD proteins appear to have no effect on integration efficiency in vitro, yet they alter the frequency of integration events in vivo (Fig. 6 and (Yoder et al., 2006). As a nuclear resident, it is likely that TFIIH does not interact with retroviral cDNA until the PIC enters the nucleus (Coin et al., 2006). However, differences in HIV cDNA accumulation have been observed at time points before entry to the nucleus in cycling cells (Yoder et al., 2006). To determine the subcellular localization of TFIIH mediated cDNA degradation, XPB cells were arrested at G1/S by treating with aphidicolin for 18 hours and infecting with an HIV vector in the continued presence of aphidicolin. Aphidicolin is an inhibitor of cellular DNA replication polymerases and induces accumulation of cells in G1/S phases of the cell cycle (Supplemental Fig. 1). The numbers of late reverse transcripts (LRT) and 2LTR circles per cell at 6, 21, 30, 48, and 72 hpi were determined by qPCR (Fig. 7A and B, respectively). 2LTR circles serve as an indicator of nuclear entry since this form of cDNA is only found in the nucleus (Bukrinsky et al., 1992). The appearance of 2LTR circles indicates that although the cells are arrested, HIV PICs are able to enter the nucleus (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Infection of XPB cell lines in the presence of aphidicolin. XPB-wt (open diamonds) and XPB(F99S) (filled squares) cells were treated with 1 μg/ml aphidicolin for 18 hours before infection and arrested at G1/S. HIV vector particles were added in the continued presence of aphidicolin. DNA was collected at 6, 24, 30, 48, and 72 hours post infection and analyzed by qPCR for the accumulation of (A) HIV late reverse transcripts (LRT), (B) HIV 2LTR circles. The 18S gene was quantified to yield the number of HIV cDNAs per cell. (C and D) XPB-wt (open diamonds) and XPB(F99S) (filled squares) cells were treated with 1 μg/ml aphidicolin for 18 hours before infection and arrested at G1/S. MMLV vector particles were added in the continued presence of aphidicolin. Aphidicolin was removed at 24 hpi. DNA was collected at 8, 24, 27, 30, and 48 hours post infection and analyzed by qPCR for the accumulation of (C) MMLV late reverse transcripts (LRT) and (D) MMLV 2LTR circles. The 18S gene was quantified to yield the number of MMLV LRT per cell. Error bars indicate the standard deviation between duplicates in two independent experiments.

At the 6 hpi there are no detectable HIV 2LTR circles, indicating that the HIV cDNA is still in the cytoplasm while TFIIH proteins are sequestered in the nucleus. At this early time point the amount of LRT is similar for both XPB NER mutant and XPB-wt cells (Fig. 7A). This suggests that cDNA synthesis by reverse transcriptase in the cytoplasm of arrested cells is not affected by nuclear XPB. 2LTR circles begin to appear at 21 hpi indicating that the HIV cDNA has begun to enter the nucleus (Fig. 7B). At this time point differences in the number of cDNA molecules in mutant and wild type cells begin to appear. Cells expressing wild type XPB have fewer cDNA molecules at 21 hpi compared to XPB(F99S). XPB-wt cells have 37% LRT compared to XPB(F99S) cells at 21 hpi (Fig. 7A). This observation suggests that although a similar number of cDNA molecules are synthesized and enter the nucleus, the wild type XPB cells display a more robust cDNA degradation activity.

Unlike HIV, MMLV is not able to enter the nucleus of arrested cells. XPB(F99S) and XPB-wt cells were treated with aphidicolin for 18 hours to induce a G1/S arrest (Supplemental Fig. 1). These cells were infected with MMLV in the continued presence of aphidicolin for 24 hours (Fig. 7C and D). At 24 hpi, aphidicolin was removed; this allows the cell cycle to resume, the nuclear envelope to breakdown, and MMLV cDNA to enter the nucleus. DNA was purified at 8, 24, 27, 30, and 48 hpi and analyzed by qPCR for MMLV LRTs and 2LTR circles (Fig. 7C and D, respectively). 2LTR circles are an indicator of MMLV cDNA entry to the nucleus and are only observed at time points after aphidicolin is removed (Fig 7D). At 8 hpi and 24 hpi when aphidicolin is present, the accumulation of MMLV LRTs appears similar in XPB-wt and XPB(F99S) cells (8 hpi P=0.76, 24 hpi P=0.80). When aphidicolin is removed from the culture, XPB-wt cells showed an immediate decline in MMLV cDNA. In contrast, the XPB(F99S) cells do not degrade the MMLV cDNA to the same extent as the XPB-wt cells (Fig. 7C, 27 hpi P=0.0004, 30 hpi P=0.01, 48 hpi P=0.0002). The degradation of MMLV cDNA only occurs when the aphidicolin mediated cell cycle arrest is removed and is less in the presence of a DNA repair mutant XPB. When compared with the HIV infection studies (Fig. 7 A and B), these results are consistent with the conclusion that XPB mediated cDNA degradation coincides with entry to the nucleus.

DISCUSSION

The fates of retroviral cDNA include degradation, 1LTR or 2LTR circle formation, and integration. Only the integrated provirus is able to continue the viral life cycle (Coffin, Hughes, and Varmus, 1997). A significant fraction of complete reverse transcripts will not become an integrated provirus (Barbosa et al., 1994; Brussel and Sonigo, 2003; Butler, Johnson, and Bushman, 2002; Van Maele et al., 2003; Vandegraaff et al., 2001). The dead-end fates of circularization and degradation appear to effectively defend the host genome from invading DNA molecules. Retroviral 2LTR circles are only found in the nucleus and may be formed by host DNA repair factors (Bukrinsky et al., 1992; Li et al., 2001). This study suggests that at least a fraction of retroviral cDNA degradation events also occur in the nucleus and involve host DNA repair proteins.

A previous study of XPB and XPD showed differences in the accumulation of cDNA at early time points before nuclear entry in cycling cells (Yoder et al., 2006). To more accurately determine the subcellular localization of TFIIH mediated cDNA degradation, we arrested XPB cell lines with aphidicolin. At the earliest time point in the presence of aphidicolin, the number of HIV late reverse transcripts was the same in both NER mutant and wild type cells. Detection of 2LTR circles indicated when HIV cDNA entered the nucleus. The appearance of 2LTR circles correlated with a significant difference in cDNA accumulation between wild type and mutant cells. Infection of arrested cells with MMLV also showed that cDNA accumulation was similar in XPB-wt and XPB(F99S) cells. Only when aphidicolin was removed and cells could resume cycling did the MMLV cDNA begin to degrade in both cell lines. The degradation of MMLV cDNA degradation was greater in XPB-wt cells compared to XPB(F99S) cells. These results strongly suggest that cDNA degradation occurs in the nucleus and that wild type TFIIH protein XPB participates in the degradation of retroviral cDNA.

The TFIIH complex is required for basal transcription and NER (Lehmann, 2001). Each of these processes involves a distinct subset of cellular partners. Additional factors that participate in TFIIH mediated degradation of retroviral cDNA remain to be identified. Other host defense pathways, including APOBEC3G and proteasome associated pathways, are apparently not related to the XPB/XPD cDNA degradation pathway. Additionally, TFIIH transcription activity does not appear to be involved in retroviral defense either directly or indirectly by transcribing additional genes. While NER associated mutants of XPB and XPD reduce cDNA degradation, previous studies indicated that other NER factors, including XPA and XPC, do not participate in cDNA degradation (Yoder et al., 2006) and data not shown). Additional proteins that participate in the TFIIH mediated cDNA degradation pathway, including an exonuclease or endonuclease, may not be part of transcription or NER pathways and remain to be identified.

The mechanism of TFIIH cDNA degradation is also mysterious. The substrate preference of XPD has been exhaustively evaluated in vitro (Rudolf et al., 2010). The XPD helicase will unwind a substrate with a 5' overhang or a 5' flap of DNA, but not a 3' overhang or 3' flap. The ends of retroviral cDNA are 5' dinucleotide overhangs after processing by integrase (Coffin, Hughes, and Varmus, 1997). Lentiviruses also display a 5' flap of DNA at the central polypurine tract (cPPT). This feature is likely not required for TFIIH mediated cDNA degradation since MMLV does not have a cPPT. Additional studies should identify the features of the retroviral cDNA that are required for cDNA degradation.

There are few identified individuals world-wide with mutations of XPB, 9 patients, or XPD, less than 60 patients (Lehmann, 2001; Oh et al., 2006). It is statistically unlikely that individuals with mutations of XPB or XPD will acquire a retroviral infection. However, there are two XPD single nucleotide polymorphisms, XPD(D312N) and XPD(K751Q), that change the coding sequence of the protein and occur at >1% frequency in the general population (Clarkson and Wood, 2005). Many studies have evaluated the role of XPD polymorphisms in the development of cancer; careful review suggests that an association of lung cancer and XPD(D312N) and XPD(K751Q) is unclear (Benhamou and Sarasin, 2005). However, a recent study of XPD(K751Q) and HIV infection concluded that this polymorphism may associate with accelerated disease progression (Sobti et al., 2010). Further study will be required to assess any role of TFIIH polymorphisms on HIV infection and disease progression.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Cell lines

All media reagents were obtained from Invitrogen. XPB cell lines include the XP/CS patient derived cell line XPCS2BASV expressing the mutant allele XPB(F99S) (referred to in the text as XPB(F99S)) and the XPCS2BASV cell line complemented with the wild type XPB allele (XPCS2BASV+LXPBSNA, referred to in the text as XPB-wt) (Riou et al., 1999). The second XPB allele in the XPB(F99S) cell line is a truncation mutant that is not expressed (Oh et al., 2006). XPB(F99S) derived cell lines were transformed with SV40 large T antigen (Riou et al., 1999). XPB(F99S) and XPB-wt cell lines were grown in DMEM/F12 media supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum, penicillin, streptomycin, and L-glutamine.

XPD cell lines include the XP patient derived cell line XP6BE(SV40) encoding two XPD mutations, one allele encodes a 78 nucleotide deletion which is not expressed and the second allele encodes the expressed XPD(R683W) mutation (referred to in the text as XPD(R683W) (Gozukara et al., 1994). This XPD(R683W) mutant cell line was complemented with the wild type XPD allele and called here XPD-wt (XP6BE-ER2-9 (Gozukara et al., 1994). The XPD(R683W) derived cell lines were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum, penicillin, streptomycin, and L-glutamine. The XPD-wt cell line was also supplemented with 600 μg/ml G418.

Drugs

Cells were treated with varying amounts of α-amanitin (Sigma), cycloheximide (Sigma), or 5,6-Dichloro-1-b-D-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole (DRB, Calbiochem) for 24 hours to determine the highest tolerated dose for each cell line (data not shown). The cytotoxicity was similar for all the cell lines and cells were treated with 25 μg/ml α-amanitin, 100 μg/ml cycloheximide, or 10 μM DRB. The XP cell lines were also treated with varying concentrations of proteasome inhibitors to determine the highest tolerable dose for each cell line (data not shown). XPB-wt and XPB(F99S) cells were treated with 2 μM lactacystin, 2 μM MG132, 2 μM clasto-lactacystin β-lactone, 5 μM calpain inhibitor I (Calbiochem). XPD-wt and XPD(R683W) cells were treated with 2.5 μM lactacystin, 0.5 μM MG132, 1 μM clasto-lactacystin β-lactone, 50 μM calpain inhibitor I. Cells were treated with varying concentrations of aphidicolin (Sigma) to determine the minimal dosage required to arrest cells at G1/S. XPB(F99S) and XPB-wt cells were treated with 1 μg/ml aphidicolin.

Infections

HIV based retroviral vector particles were produced by transfecting 293T cells with three plasmids: an envelope plasmid coding the VSV-G protein (Stratagene), a packaging construct derived from HIV pΔR8.2 (Zufferey et al., 1997), and a genomic RNA construct also derived from HIV but coding only for GFP (Follenzi et al., 2000). A fourth plasmid encoding either human APOBEC3G or African green monkey APOBEC3G was included in the transfection for some experiments (a kind gift from N. Landau, NYU, (Mariani et al., 2003). MMLV based retroviral vector particles were produced similarly to HIV but using an MMLV derived packaging construct (HIT60) and genomic RNA construct pLEGFP-C1 (Cannon et al., 1996) and Clontech). The MMLV genomic construct also coded only a GFP gene. Following transfection, supernatants were collected, filtered to remove producer cells, and treated with DNaseI (Roche, (Lu et al., 2004).

For infections, cells were plated at equal densities in 6 well dishes. Cell lines were infected with the HIV or MMLV based retroviral vector particles at two multiplicites of infection (MOI) in the presence of 10 μg/ml DEAE dextran (Sigma) in triplicate. The media was replaced after two hours in the continued presence of drug where indicated. For flow cytometry analysis of infection efficiency, after 72 hours the cells were trypsinized, washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma), and analyzed for GFP expression by flow cytometry (BD FACS Calibur and Cellquest software).

Quantitative PCR

Cells were trypsinized and washed with PBS at indicated time points following infection. Total DNA was purified by DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen). HIV DNA forms were quantified with previously described primer sets to late reverse transcripts, and 2LTR circles (Butler, Hansen, and Bushman, 2001; Chiu et al., 2005). The MMLV LRT primer set spans the MMLV primer binding site and includes primers KY366 5' AGCTTACCTCCCGGTGGTGG 3', KY372 5' TCTCCTCTGAGTGATTGACTACC 3', and probe KY364 5' FAM-CATTTGGGGGCTCGTCCGGGAT-TAMRA 3'. The MMLV 2LTR circle primer set is primers KY367 5' GCGTTACTTAAGCTAGCTTGCC 3' and KY368 5' GCGTCGCCCGGGTACCCG 3' and probe KY369 5' FAM-GGTAGTCAATCACTCAGAGGAG-TAMRA 3'. The number of cellular genomes present per sample was quantified by primers to the 18S gene (Applied Biosystems). Absolute quantitation was performed with known amounts of plasmid standards or cellular genomes with Taqman mastermix in an ABI Prism 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) at the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center Nucleic Acid Shared Resource. The amount of retroviral DNA was divided by the number of cellular genomes to yield the amount of retroviral DNA per cell. All qPCR reactions were performed in triplicate.

Integration reactions in vitro

Cells were infected with HIV based retroviral vector particles as described (Hansen et al., 1999). After 6 hours, the cells were trypsinized and washed with Buffer K (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM KCl, and 5 mM MgCl2). Cells were resuspended in Buffer K with 1 mM DTT, 0.5% NP-40, and protease inhibitors and incubated on ice for 10 min. The PIC extracts were spun at 3000×g for 3 min and then 10,000×g for 3 min. The supernatant was frozen with liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. 100 ng genomic DNA from uninfected 293T cells was added to the PICs and incubated at 37°C for one hour. DNA was then isolated from the integration reactions by the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen). Late reverse transcripts and integrated provirus were measured by qPCR as described (Brussel and Sonigo, 2003; Butler, Hansen, and Bushman, 2001; Lu et al., 2005; Vandegraaff et al., 2006). A negative control of HIV PICs with no target (0% integration) and a positive control of genomic DNA from infected cells passaged for multiple generations (100% integration) were included. The total amount of late reverse transcripts was measured by qPCR indicating the total number of unintegrated and integrated PICs present in each sample. 104 late reverse transcripts were amplified with 100 nM each of the previously described primers L-M667, Alu1, and Alu2, for 20 cycles (Brussel and Sonigo, 2003). The reaction products were diluted 1:10 and amplified by qPCR with 300 nM primers Lambda T and AA55M and 200 nM probe MH603 (Brussel and Sonigo, 2003; Butler, Hansen, and Bushman, 2001). The integration efficiency of HIV PICs derived from mutant cells is expressed relative to integration of HIV PICs derived from wild type cells.

Statistical Analysis

Data in Figures 1B, 1C, 2, 3, and 5 is expressed relative to no drug present. Data in Figures 1A, 4, and 6 is expressed relative to wild type cells. Flow cytometry and qPCR data was analyzed by paired t test to generate two-tail P values (GraphPad Prism 4, San Diego). P values were rounded to two significant figures.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Nathan Landau for APOBEC3G plasmids and the Ohio State University Center for Retrovirus Research for scientific discussion. This work was supported by NIH grant AI82422 (KY and RF).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Albin JS, Harris RS. Interactions of host APOBEC3 restriction factors with HIV-1 in vivo: implications for therapeutics. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2010;12:e4. doi: 10.1017/S1462399409001343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa P, Charneau P, Dumey N, Clavel F. Kinetic analysis of HIV-1 early replicative steps in a coculture system. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10(1):53–9. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benhamou S, Sarasin A. ERCC2 /XPD gene polymorphisms and lung cancer: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(1):1–14. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglione S, Byers SA, Price JP, Nguyen VT, Bensaude O, Price DH, Maury W. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication by P-TEFb inhibitors DRB, seliciclib and flavopiridol correlates with release of free P-TEFb from the large, inactive form of the complex. Retrovirology. 2007;4:47. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-4-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop KN, Holmes RK, Malim MH. Antiviral potency of APOBEC proteins does not correlate with cytidine deamination. J Virol. 2006;80(17):8450–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00839-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brussel A, Sonigo P. Analysis of early human immunodeficiency virus type 1 DNA synthesis by use of a new sensitive assay for quantifying integrated provirus. J Virol. 2003;77(18):10119–24. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.18.10119-10124.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukrinsky MI, Sharova N, Dempsey MP, Stanwick TL, Bukrinskaya AG, Haggerty S, Stevenson M. Active nuclear import of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 preintegration complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(14):6580–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler SL, Hansen MS, Bushman FD. A quantitative assay for HIV DNA integration in vivo. Nat Med. 2001;7(5):631–4. doi: 10.1038/87979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler SL, Johnson EP, Bushman FD. Human immunodeficiency virus cDNA metabolism: notable stability of two-long terminal repeat circles. J Virol. 2002;76(8):3739–47. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.8.3739-3747.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon PM, Kim N, Kingsman SM, Kingsman AJ. Murine leukemia virus-based Tat-inducible long terminal repeat replacement vectors: a new system for anti-human immunodeficiency virus gene therapy. J Virol. 1996;70(11):8234–40. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8234-8240.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu YL, Soros VB, Kreisberg JF, Stopak K, Yonemoto W, Greene WC. Cellular APOBEC3G restricts HIV-1 infection in resting CD4+ T cells. Nature. 2005;435(7038):108–14. doi: 10.1038/nature03493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson SG, Wood RD. Polymorphisms in the human XPD (ERCC2) gene, DNA repair capacity and cancer susceptibility: an appraisal. DNA Repair (Amst) 2005;4(10):1068–74. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Varmus HE. Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coin F, Oksenych V, Egly JM. Distinct roles for the XPB/p52 and XPD/p44 subcomplexes of TFIIH in damaged DNA opening during nucleotide excision repair. Mol Cell. 2007;26(2):245–56. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coin F, Proietti De Santis L, Nardo T, Zlobinskaya O, Stefanini M, Egly JM. p8/TTD-A as a repair-specific TFIIH subunit. Mol Cell. 2006;21(2):215–26. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchfield JW, Coligan JE, Folks TM, Butera ST. Casein kinase II is a selective target of HIV-1 transcriptional inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(12):6110–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubaele S, Proietti De Santis L, Bienstock RJ, Keriel A, Stefanini M, Van Houten B, Egly JM. Basal transcription defect discriminates between xeroderma pigmentosum and trichothiodystrophy in XPD patients. Mol Cell. 2003;11(6):1635–46. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L, Arvai AS, Cooper PK, Iwai S, Hanaoka F, Tainer JA. Conserved XPB core structure and motifs for DNA unwinding: implications for pathway selection of transcription or excision repair. Mol Cell. 2006;22(1):27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnet CM, Haseltine WA. Integration of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 DNA in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(11):4164–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follenzi A, Ailles LE, Bakovic S, Geuna M, Naldini L. Gene transfer by lentiviral vectors is limited by nuclear translocation and rescued by HIV-1 pol sequences. Nat Genet. 2000;25(2):217–22. doi: 10.1038/76095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg EC, Meira LB. Database of mouse strains carrying targeted mutations in genes affecting biological responses to DNA damage Version 7. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5(2):189–209. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giglia-Mari G, Coin F, Ranish JA, Hoogstraten D, Theil A, Wijgers N, Jaspers NG, Raams A, Argentini M, van der Spek PJ, Botta E, Stefanini M, Egly JM, Aebersold R, Hoeijmakers JH, Vermeulen W. A new, tenth subunit of TFIIH is responsible for the DNA repair syndrome trichothiodystrophy group A. Nat Genet. 2004;36(7):714–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff SP. Retrovirus restriction factors. Mol Cell. 2004;16(6):849–59. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozukara EM, Parris CN, Weber CA, Salazar EP, Seidman MM, Watkins JF, Prakash L, Kraemer KH. The human DNA repair gene, ERCC2 (XPD), corrects ultraviolet hypersensitivity and ultraviolet hypermutability of a shuttle vector replicated in xeroderma pigmentosum group D cells. Cancer Res. 1994;54(14):3837–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groschel B, Bushman F. Cell cycle arrest in G2/M promotes early steps of infection by human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 2005;79(9):5695–704. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5695-5704.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen MS, Smith GJ, 3rd, Kafri T, Molteni V, Siegel JS, Bushman FD. Integration complexes derived from HIV vectors for rapid assays in vitro. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17(6):578–82. doi: 10.1038/9886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RS, Bishop KN, Sheehy AM, Craig HM, Petersen-Mahrt SK, Watt IN, Neuberger MS, Malim MH. DNA deamination mediates innate immunity to retroviral infection. Cell. 2003;113(6):803–9. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00423-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann AR. The xeroderma pigmentosum group D (XPD) gene: one gene, two functions, three diseases. Genes Dev. 2001;15(1):15–23. doi: 10.1101/gad.859501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Olvera JM, Yoder KE, Mitchell RS, Butler SL, Lieber M, Martin SL, Bushman FD. Role of the non-homologous DNA end joining pathway in the early steps of retroviral infection. EMBO J. 2001;20(12):3272–81. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.12.3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R, Limon A, Devroe E, Silver PA, Cherepanov P, Engelman A. Class II integrase mutants with changes in putative nuclear localization signals are primarily blocked at a postnuclear entry step of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J Virol. 2004;78(23):12735–46. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.12735-12746.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R, Vandegraaff N, Cherepanov P, Engelman A. Lys-34, dispensable for integrase catalysis, is required for preintegration complex function and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J Virol. 2005;79(19):12584–91. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.19.12584-12591.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangeat B, Turelli P, Caron G, Friedli M, Perrin L, Trono D. Broad antiretroviral defence by human APOBEC3G through lethal editing of nascent reverse transcripts. Nature. 2003;424(6944):99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature01709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani R, Chen D, Schrofelbauer B, Navarro F, Konig R, Bollman B, Munk C, Nymark-McMahon H, Landau NR. Species-specific exclusion of APOBEC3G from HIV-1 virions by Vif. Cell. 2003;114(1):21–31. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00515-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MD, Farnet CM, Bushman FD. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 preintegration complexes: studies of organization and composition. J Virol. 1997;71(7):5382–90. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5382-5390.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh KS, Khan SG, Jaspers NG, Raams A, Ueda T, Lehmann A, Friedmann PS, Emmert S, Gratchev A, Lachlan K, Lucassan A, Baker CC, Kraemer KH. Phenotypic heterogeneity in the XPB DNA helicase gene (ERCC3): xeroderma pigmentosum without and with Cockayne syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2006;27(11):1092–103. doi: 10.1002/humu.20392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi M, Yang R, Aiken C. Cyclophilin A-dependent restriction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid mutants for infection of nondividing cells. J Virol. 2008;82(24):12001–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01518-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranish JA, Hahn S, Lu Y, Yi EC, Li XJ, Eng J, Aebersold R. Identification of TFB5, a new component of general transcription and DNA repair factor IIH. Nat Genet. 2004;36(7):707–13. doi: 10.1038/ng1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riou L, Zeng L, Chevallier-Lagente O, Stary A, Nikaido O, Taieb A, Weeda G, Mezzina M, Sarasin A. The relative expression of mutated XPB genes results in xeroderma pigmentosum/Cockayne's syndrome or trichothiodystrophy cellular phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8(6):1125–33. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.6.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy R, Adamczewski JP, Seroz T, Vermeulen W, Tassan JP, Schaeffer L, Nigg EA, Hoeijmakers JH, Egly JM. The MO15 cell cycle kinase is associated with the TFIIH transcription-DNA repair factor. Cell. 1994;79(6):1093–101. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolf J, Rouillon C, Schwarz-Linek U, White MF. The helicase XPD unwinds bubble structures and is not stalled by DNA lesions removed by the nucleotide excision repair pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(3):931–41. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuitemaker H, Kootstra NA, Fouchier RA, Hooibrink B, Miedema F. Productive HIV-1 infection of macrophages restricted to the cell fraction with proliferative capacity. EMBO J. 1994;13(24):5929–36. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06938.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz O, Marechal V, Friguet B, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Heard J-M. Antiviral activity of the proteasome on incoming Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1. J Virology. 1998;72:3845–3850. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3845-3850.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobti RC, Berhane N, Mahdi SA, Kler R, Hosseini SA, Kuttiat V, Wanchu A. Impact of ERCC2 gene polymorphism on HIV-1 disease progression to AIDS among North Indian HIV patients. Mol Biol Rep. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-9958-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Maele B, De Rijck J, De Clercq E, Debyser Z. Impact of the central polypurine tract on the kinetics of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vector transduction. J Virol. 2003;77(8):4685–94. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4685-4694.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandegraaff N, Devroe E, Turlure F, Silver PA, Engelman A. Biochemical and genetic analyses of integrase-interacting proteins lens epithelium-derived growth factor (LEDGF)/p75 and hepatoma-derived growth factor related protein 2 (HRP2) in preintegration complex function and HIV-1 replication. Virology. 2006;346(2):415–26. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandegraaff N, Kumar R, Burrell CJ, Li P. Kinetics of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV) DNA integration in acutely infected cells as determined using a novel assay for detection of integrated HIV DNA. J Virol. 2001;75(22):11253–60. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.11253-11260.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yankulov K, Yamashita K, Roy R, Egly JM, Bentley DL. The transcriptional elongation inhibitor 5,6-dichloro-1-beta-D-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole inhibits transcription factor IIH-associated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(41):23922–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.23922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder K, Sarasin A, Kraemer K, McIlhatton M, Bushman F, Fishel R. The DNA repair genes XPB and XPD defend cells from retroviral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(12):4622–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509828103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zufferey R, Nagy D, Mandel RJ, Naldini L, Trono D. Multiply attenuated lentiviral vector achieves efficient gene delivery in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15(9):871–5. doi: 10.1038/nbt0997-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.