Abstract

Mutations in glycyl-, tyrosyl-, and alanyl-tRNA synthetases (GARS, YARS and AARS respectively) cause autosomal dominant Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, and mutations in Gars cause a similar peripheral neuropathy in mice. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (ARSs) charge amino acids onto their cognate tRNAs during translation; however, the pathological mechanism(s) of ARS mutations remains unclear. To address this, we tested possible mechanisms using mouse models. First, amino acid mischarging was discounted by examining the recessive “sticky” mutation in alanyl-tRNA synthetase (Aarssti), which causes cerebellar neurodegeneration through a failure to efficiently correct mischarging of tRNAAla. Aarssti/sti mice do not have peripheral neuropathy, and they share no phenotypic features with the Gars mutant mice. Next, we determined that the Wallerian degeneration slow (Wlds) mutation did not alter the Gars phenotype. Therefore, no evidence for misfolding of GARS itself or other proteins was found. Similarly, there were no indications of general insufficiencies in protein synthesis caused by Gars mutations based on yeast complementation assays. Mutant GARS localized differently than wild type GARS in transfected cells, but a similar distribution was not observed in motor neurons derived from wild type mouse ES cells, and there was no evidence for abnormal GARS distribution in mouse tissue. Both GARS and YARS proteins were present in sciatic axons and Schwann cells from Gars mutant and control mice, consistent with a direct role for tRNA synthetases in peripheral nerves. Unless defects in translation are in some way restricted to peripheral axons, as suggested by the axonal localization of GARS and YARS, we conclude that mutations in tRNA synthetases are not causing peripheral neuropathy through amino acid mischarging or through a defect in their known function in translation.

Keywords: DI-CMTC, HSMN2D, hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy, dSMAV, distal spinal muscular atrophy type V, amino acylation, axonal translation

Introduction

Mutations in three genes encoding aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (ARSs) have recently been associated with dominant peripheral neuropathies (Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease) (Antonellis et al., 2003; Jordanova et al., 2006; Latour et al., 2010). The extent to which these conditions share common pathogenic mechanisms and what these mechanisms may be remain unclear. We therefore compared possible pathogenic mechanisms in mice with mutations in two ARS genes, and examined other phenotypes related to the known function of these enzymes.

The canonical activity of ARSs is to charge amino acids onto their cognate tRNAs so they can function in translation (Ibba and Soll, 2004; Schimmel, 2008). As such, these enzymes are responsible for maintaining the fidelity of the genetic code. The mammalian nuclear genome contains 37 ARS genes, generally with two genes encoding an enzyme for each amino acid - one encoding the cytosolic enzyme, the other encoding the enzyme that functions in mitochondrial protein synthesis (Antonellis and Green, 2008). In some cases, a single gene encodes both the cytosolic and mitochondrial forms of the protein by using alternative start codons, as is the case for glycyl-tRNA synthetase (Gars, or GARS for the protein). Thus, each ARS gene is essential for its nonredundant role in translation.

Human mutations in mitochondrial aspartyl-tRNA synthetase (DARS2) and mitochondrial arginyl-tRNA synthetase (RARS2) cause leukoencephalopathy with brain stem and spinal cord involvement and lactate elevation (LBSL), and pontocerebellar hypoplasia and multiple mitochondrial respiratory-chain defects, respectively (Edvardson et al., 2007; Scheper et al., 2007). In both cases, the mutations are in the genes encoding the mitochondrial forms of the enzymes, and the disease phenotypes may be a reflection of mitochondrial dysfunction arising from impaired protein synthesis.

A recessive mutation in the cytosolic form of alanyl-tRNA synthetase (the sticky mutation, Aarssti) causes a neurological phenotype in mice through a different mechanism (Lee et al., 2006). This mutation is a single amino acid change in the editing domain of AARS (A734E), causing a subtle but significant decrease in the ability of AARS to proofread mischarged tRNAAla. The most common mischarging of this tRNA is expected to be with glycine or serine, given the molecular dimensions of the enzyme’s active site and data from editing deficient bacterial alanyl-tRNA synthetase (Beebe et al., 2008; Guo et al., 2009). The Aarssti homozygous mice have degeneration of Purkinje cells that contain ubiquitin inclusions as well as other non-neuronal phenotypes such as trichodystrophy. Protein misfolding is caused by a low level of amino acid misincorporation in place of alanine residues across the entire proteome, resulting in neurodegeneration.

In addition, three human peripheral neuropathies, Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 2D (CMT2D), Dominant Intermediate Charcot-Marie-Tooth type C (DI-CMTC), and a third recently characterized form of CMT2 are caused by mutations in glycyl-tRNA synthetase (GARS), tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (YARS), and alanyl-tRNA synthetase (AARS) respectively (Antonellis et al., 2003; Jordanova et al., 2006; Latour et al., 2010). Interestingly, mutations in DARS2 also cause an axonal neuropathy in some patients (Isohanni et al., 2010), and a patient with mutations in lysyl-tRNA synthetase (KARS) has also recently been identified (McLaughlin et al., 2010). This patient carries compound heterozygous mutations including an amino acid substitution (L133H) that causes a severe reduction in tRNA charging activity, and a frame shift (Y173SerfsX7) that causes a presumed null allele. Severe neurological and behavior phenotypes were present, including an axonal neuropathy. While there may be pathological gain-of-function effects of the point mutation, a loss-of-function of KARS activity seems likely to be contributing to the severity of the phenotype.

The mutations in YARS that cause DI-CMTC are proposed to be partial loss-of-function or dominant-negative changes, based on yeast complementation studies and altered subcellular localization of the mutant protein in transfected cells (Jordanova et al., 2006). Studies in Drosophila also indicate that expression of mutant forms of YARS specifically in neurons results in axonal defects, but mammalian models of DI-CMTC are not yet available (Storkebaum et al., 2009). Mutant forms of the GARS protein also have altered distribution, but there is a less clear correlation between retained enzymatic activity and the disease phenotype (Antonellis et al., 2006; Nangle et al., 2007). Mice with a spontaneous, dominant mutation in Gars (GarsNmf249/+) develop a peripheral neuropathy very similar to human CMT2D (Seburn et al., 2006). This phenotype is not evident in mice heterozygous for a loss-of-function gene trap allele that decreases expression of Gars at the RNA level with a corresponding reduction in enzyme activity in tissue homogenates. Similar but milder neuromuscular dysfunction is also seen in second, dominant Gars allele (GarsC201R) (Achilli et al., 2009). These results suggest that the disease phenotype of CMT2D requires the expression of the mutant protein and this interpretation is supported by studies of protein expression in patient cell lines (Antonellis et al., 2006). The neuropathy mutation in AARS affects a residue (R329H) critical for binding and aminoacylation of tRNAAla based on studies of the bacterial protein, but how this mutation affects the function of the mammalian protein has not been tested and a mischarging mechanism analogous to the Aarssti mouse has been suggested (Latour et al., 2010).

There are several possible mechanisms by which ARS mutations could cause disease (Motley et al., 2010). For example, disease-causing mutations could change the structure of the active site of the tRNA synthetase, allowing misincorporation of amino acids, analogous to the editing domain mutation in Aarssti. Indeed, GARS does not have an editing domain because its active site is normally conformationally constrained to accept only glycine, the smallest amino acid (Arnez et al., 1999; Logan et al., 1995). A crystal structure of the human GARS protein is solved, and some mutations are predicted to influence the conformation of the active site, but many are not, although this has not been experimentally tested (Xie et al., 2007).

The ARS phenotypes could also arise from defects in protein synthesis caused by insufficient enzyme activity. In some GARS mutations, enzyme activity assayed in vitro is reduced, and in other cases it is not (Antonellis et al., 2006; Nangle et al., 2007; Seburn et al., 2006). Even in cases where enzymatic activity is retained, activity within cells could be compromised if the enzymes are not properly localized and therefore not available to participate in translation (Antonellis et al., 2006; Nangle et al., 2007). Furthermore, the mutant proteins could result in toxic aggregates, as noted for other neurodegenerative conditions, or they could be assuming a novel pathological function. However, the incidence of three ARS genes causing peripheral neuropathy suggests a common mechanism related to their shared function in translation.

To test these possible mechanisms, we have compared the phenotypes and pathogenic changes in the mouse Aarssti and GarsNmf249 mutations and examined GARS localization and the in vivo ability of the mutant protein to sustain protein synthesis. We conclude that Aarssti and GarsNmf249 are indeed distinct phenotypes, affecting different cell populations through different mechanisms, making it unlikely that the human GARS, YARS and AARS mutations cause amino acid misincorporation. Furthermore, if the GarsNmf249/+ phenotype arises from deficits in protein synthesis, this is unlikely to be a general phenomenon, but may represent dysfunction specifically in axons based on analyses of cell morphology, activity and localization. Consistent with this, the GARS and YARS proteins are found in peripheral axons and Schwann cells, suggesting a direct role for the protein in peripheral nerves.

Materials and Methods

Mice

The Aarssti mutation has been previously described and is maintained in a congenic C57BL/6J background (Lee et al., 2006). The GarsNmf249 and GarsC201R mutations have also been previously described (Achilli et al., 2009; Seburn et al., 2006). The GarsNmf249/+ mice used in the present studies are derived from a colony carrying a modifier locus (or loci) from CAST/EiJ (CAST) that facilitates colony maintenance. Mice on an inbred C57BL/6J background die at 6–8 weeks of age, complicating breeding and propagation of the allele. To circumvent this, a cross was performed to CAST and increased viability was seen. These modifier loci from CAST were then selected for by backcrossing to C57BL/6J for at least 5 generations. The age of onset (approximately two weeks) and severity of motor axon loss in the femoral nerve (approximately 25–30% as shown in figure 4 for example) is very similar in these mice compared to the inbred C57BL/6J strain. Therefore, these mice survive to at least 18 months of age and are appropriate for the studies described here. The basis for the increased viability is under investigation. The Wlds allele has been previously described, and the original Wlds line in a congenic C57BL/6J background was used (Coleman et al., 1998). The Thy1-YFPH transgenics used in Figure 5 are officially B6.Cg-Tg(Thy1-YFPH)2Jrs/J and are available from The Jackson Laboratory.

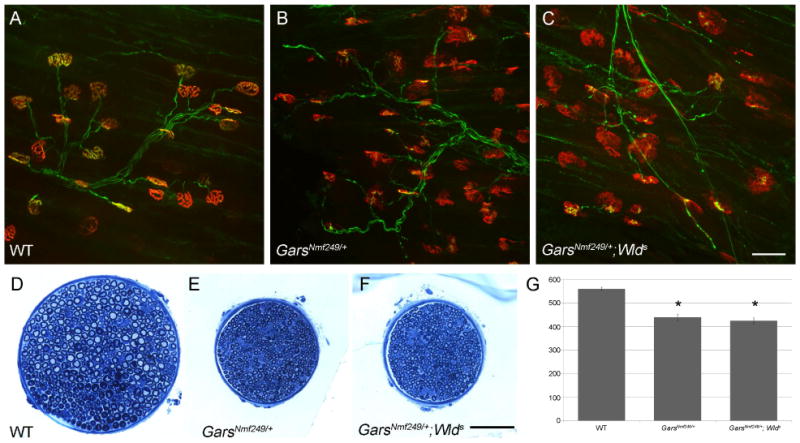

Figure 4.

Wlds does not suppress peripheral neuropathy in GarsNmf249/+. Neuromuscular junctions from the gastrocnemius were visualized in wild type (A), GarsNmf249/+ (B), and GarsNmf249/+; Wlds (C). Defects including abnormal postsynaptic morphology, partial innervation, and atrophic axons were observed in both GarsNmf249/+ and GarsNmf249/+; Wlds. D-F) The motor branch of the femoral nerve was also examined in each genotype and GarsNmf249/+ and GarsNmf249/+; Wlds nerves were similarly reduced in size and lacked large diameter myelinated axons. G) The number of myelinated axons in the motor branch of the femoral nerve for both GarsNmf249/+ and GarsNmf249/+; Wlds were significantly reduced compared to control, but were not significantly different from one another. The scale bars in C and F are 50μm.

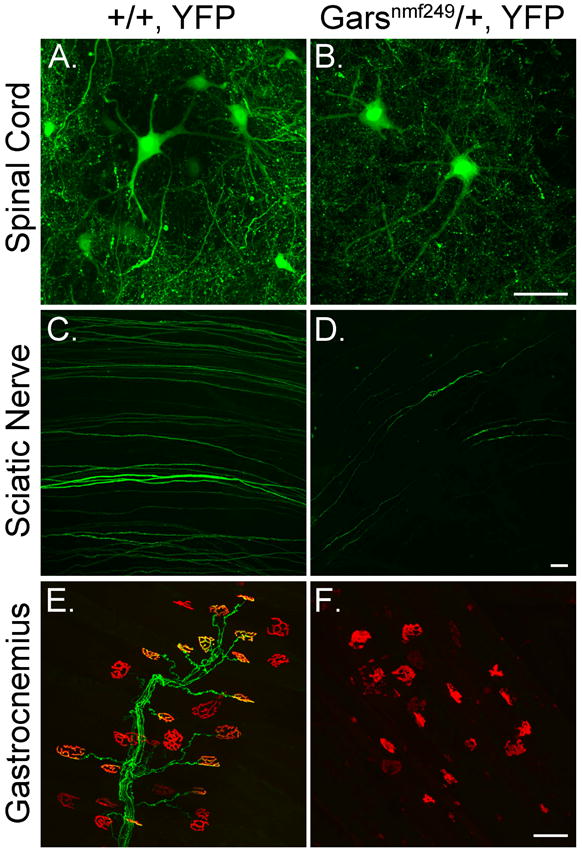

Figure 5.

Motor neuron morphology in GarsNmf249/+ mice. A, B) Projections of confocal Z-series of motor neuron cell bodies and dendrites in the spinal cord of littermate control (A) and GarsNmf249/+ mice (B) that also carry the Thy1-YFP-H transgene to label a subset of neurons revealed that cell morphology and dendrite arborization is maintained in the GarsNmf249/+ mutant spinal cord. C, D) Wholemount sciatic nerves of control mice contains many YFP-positive axons, but these are greatly reduced in number in the GarsNmf249/+ sciatic nerve, indicating axonal defects in this population of neurons. E, F) A subset of neuromuscular junctions in the gastrocnemius were YFP-positive in control mice (green), but no YFP-positive nerve terminals could be seen in the GarsNmf249/+ mice. Postsynaptic morphology, visualized with α-bungarotoxin (red) was also abnormal in the mutant muscles. Scale bars = 50 μm.

All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of The Jackson Laboratory. Mice were housed in the Research Animal Facility at The Jackson Laboratory and provided a standard NIH6% diet and water ad libitum. Numbers and ages of mice associated with each experiment are indicated below or in the text and figure legends.

Mouse ages and numbers

For peripheral nerve and NMJ analysis of Aarssti/sti (Figure 1), N=8 Aarssti/sti mice, 3 at 2.5 months, 2 at 5 months of age (2.5 and 5 month mice pooled as “young”), 3 at >1 year. For ubiquitin staining of cerebellum and spinal cord (Figure 3), Ns for ubiquitin staining: 4 Aarssti/sti at 4 weeks, 5 Aarssti/sti at 2.5-5 months, 3 GarsNmf249/+ at 4 weeks, and 4 GarsNmf249/+ at > 1year, 3 controls at 4 weeks, 2 controls at 2.5–5 months, and 2 controls at >1 year. For GARS protein localization studies (Figure 7 and Supp. Figure 1), 3 GarsNmf249/+ and 3 wild type mice were used at both 4 weeks and 10 weeks of age, and 2 wild type mice were used at 3, 6, and 12 months of age. Teased axons were prepared from 5 P23 wild type C57BL/6 mice, 3 GarsC201R/+ and 5 Gars+/+ mice at 88 days of age, and 2 GarsC201R/+ and 2 Gars+/+ mice at 57 days of age. Other experimental sample numbers and ages are given at relevant points in the text.

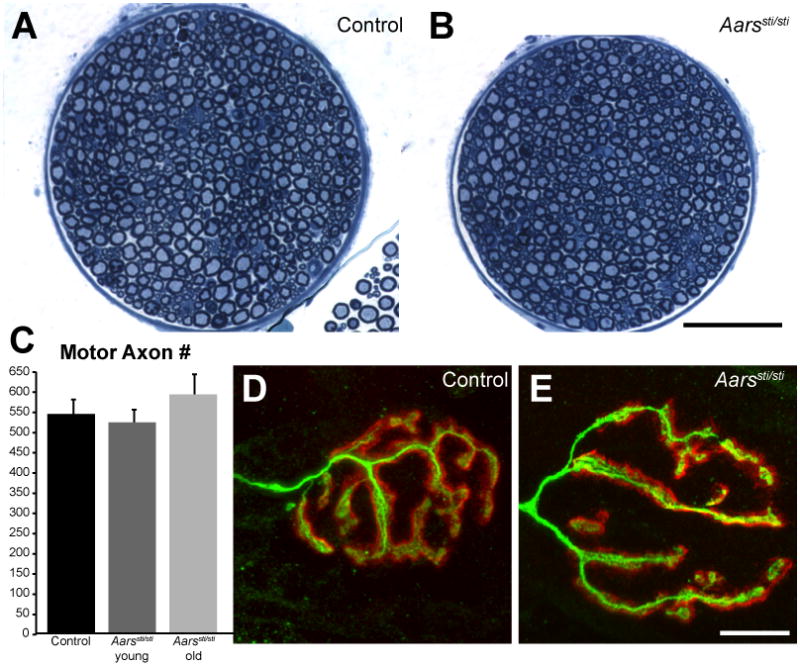

Figure 1.

Peripheral nerves are normal in Aarssti/sti mice. A, B) Cross-sections of the motor branch of the femoral nerve from control and Aarssti/sti mice (5 month old mutant shown) revealed only a uniform decrease in size in the mutant samples. C) The number of myelinated axons was not decreased in the motor branch of the femoral nerve in Aarssti/sti mice, even at greater than a year of age (young = 2-5 months, old = 14 months of age). D, E) Neuromuscular junction morphology was normal in Aarssti/sti mice, nerve terminals labeled with anti-neurofilament/anti-SV2 (green) completely overlapped the postsynaptic acetylcholine receptors labeled with α-bungarotoxin (red) in both control and mutant samples (5 month old mutant shown). Scale bar for A,B = 75 μm, for D, E = 14 μm.

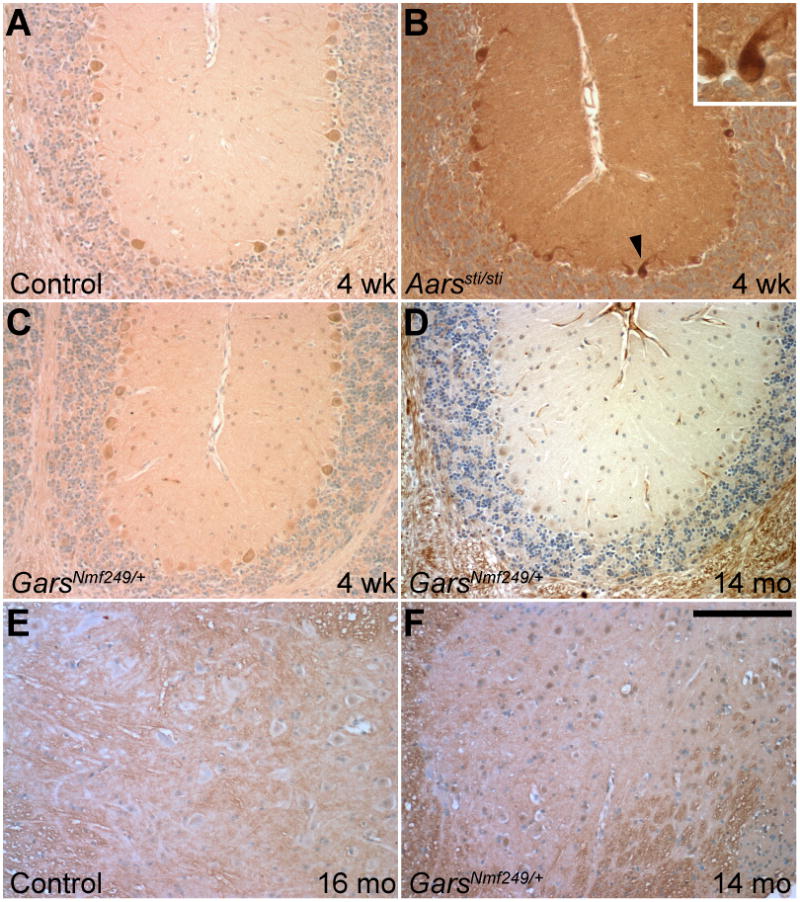

Figure 3.

Ubiquitin in cerebellum and spinal cord. A) Levels of ubiquitin staining are low in 4-week-old control cerebellum. B) The Aarssti/sti mice have much higher levels of ubiquitin staining at 4 weeks of age, filling the cytoplasm of Purkinje cells prior to their degeneration (arrowhead and inset). The GarsNmf249/+ mice do not show cerebellar ubiquitin staining that is different than control at 4 weeks of age,(C), when motor axons are actively degenerating, or at greater than 1 year (D). All images are from a similar region of the base of the rostral folia (3 and 4) of the cerebellum. In the spinal cord, motor neuron cell bodies in the ventral horn do not show ubiquitin staining in mice greater than a year of age in control (E) or GarsNmf249/+ (F) samples. Scale bar in F = 145μm.

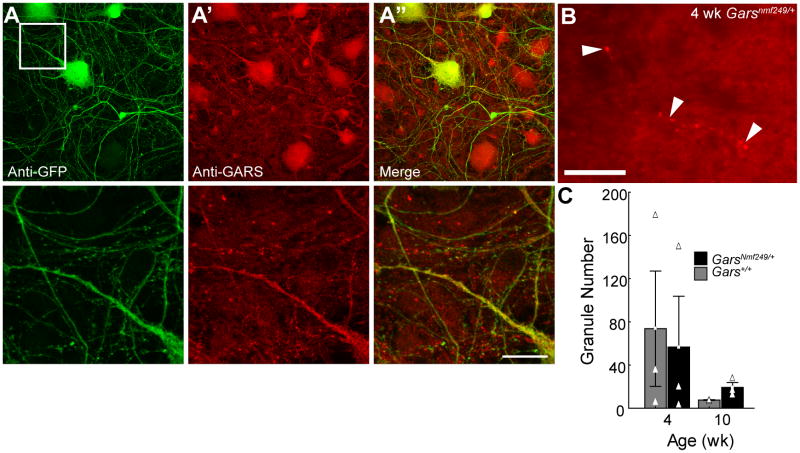

Figure 7.

GARS localization. Motor neurons derived from ES cells carrying an HB9-driven GFP transgene were labeled with anti-GFP to mark cells that had assumed a motor neuron fate (A) and anti-GARS (A’). In the merged image (A”), many puncta of GARS staining are not associated with GFP-positive processes. Higher magnification views of the boxed region in A are shown below. B) Cross sections of spinal cord from control and GarsNmf249/+ (4 week old mutant shown) mice were labeled with anti-GARS. Granules (arrowheads) were observed that appear to associate with cell processes, but the number was highly variable and did not significantly correlate with sex, age, or genotype (C). The scale bar in A” is 56 μm for the low magnification views and 14 μm for the high magnification views below, the scale in B is 24 μm.

Analysis of peripheral nerves

Peripheral nerve axon number was analyzed as described previously (Seburn et al., 2006). In brief, the motor and sensory branches of the femoral nerve were dissected free and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, 2% glutaraldehyde, in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer. Samples were then processed for transmission electron microscopy and embedded in Epon resin. Thick sections (0.5 μm) were cut and stained with Toluidine Blue to visualize myelin, and counts of myelinated axon profiles were performed by light microscopy. In all cases, at least three mice were examined for each genotype. Student’s two-tailed ttest was used to test for significant differences between each population unless otherwise noted in the text, p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Immunocytochemistry

For calbindin staining, tissue was fixed with 4% buffered paraformaldehyde and processed for paraffin embedding. Using a microtome, 4 μm sagittal sections of cerebellum or horizontal sections of lumbar spinal cord were cut and stained using anti-calbindin (D-280, Swant) with secondary antibody and signal detection using the ABC kit (Vector) and diaminobenzidine (Zymed). Ubiquitin staining was performed similarly, except tissue was fixed in acetic acid/methanol and an antigen retrieval step (microwave boiling for 5 minutes in 0.01M citrate, pH 6.0) was used prior to application of the primary antibody (Cell Signal Technologies, mAb).

Neuromuscular junctions were visualized in 150 μm vibratome sections of muscles fixed in 2% buffered paraformaldehyde. Sections were incubated with a cocktail of primary monoclonal antibodies (anti-SV2 (DSHB) and anti-neurofilament (2H3, DSHB)), following rinses, they were then stained with Alexa488 anti-mouse IgG1 and Alexa 594 conjugated α-bungarotoxin to label postsynaptic acetylcholine receptors. Samples were imaged on Leica SP2 or SP5 confocal microscopes, and Z-series projections are shown.

GARS immunocytochemistry and quantification

The GARS protein localization was examined in tissue sections by immunocytochemistry using a rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against recombinant human GARS protein (Nangle et al., 2007). Sagittal sections of cerebellum and cross sections of spinal cord were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, cryostat sectioned, stained with the antibody at a 1:200 dilution, and signals were detected using an Alexa584 conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody. All images were collected using a Nikon Eclipse 600 fluorescence microscope with a SPOT-RT digital camera. Images were exposure matched and samples were processed (tissue prepared, sectioned, and stained) in parallel in all cases where direct comparisons between ages or genotypes were being made. Fluorescence intensities were quantified using NIH-ImageJ software and the statistical significance of intensity differences were tested using Student’s two-tailed t-test. At least three mice of each age and genotype were used in these studies, except the aging time-course of wild type mice (Supp. figure 1) where only two mice at each time point were used. The staining pattern was confirmed using a second, independently generated anti-GARS anti-serum (Antonellis et al., 2006). Background fluorescence levels were determined using control slides in which the primary antibody was omitted during the staining, and these background values, if measurable, were subtracted from the fluorescence intensities presented.

Teased axons were prepared as described in (Arroyo et al., 2004). Anti-GARS staining intensities were quantified in individual confocal sections to correct for intensity differences resulting from the larger volume of large diameter axons. All nerves were double labeled with anti-neurofilament (2H3, DSHB) with an Alexa 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG1 secondary antibody (Invitrogen). Staining was assessed only in nerves with strong neurofilament immunoreactivity as an indicator of good fixation and permeabilization, as well as an indicator of the center of the axon. GARS was labeled with a rabbit polyclonal serum against human GARS (Nangle et al., 2007), as well as a commercial anti-serum (Abcam, ab42905), both at 1:100 dilution, and using a CY3-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch). YARS was labeled with a Goat polyclonal antibody at 1:100 dilution (Santa Cruz, sc26209) and an Alexa594-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen). All staining protocols were tested with the primary antibodies omitted, secondary antibody cross reactivity was also tested and found to be negative.

GARS localization was examined in vitro in transfected MN-1 cells as previously described (Antonellis et al., 2006), and in ES cell-derived motor neurons generated from mouse with an Hb9-driven GFP transgenic marker of motor neuron lineages. The mouse motor neuron cell line MN-1 (Salazar-Grueso et al., 1991) was cultured in DMEM growth medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM L-glutamine under standard incubation conditions. Constructs containing wild-type or P234KY GARS tagged with EGFP or no insert were generated as previously described and transfected into MN-1 cells using the lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Antonellis et al., 2006). For each reaction, 2.35 μl of lipofectamine 2000 and 250 μl of OptiMEM I minimal growth medium (Invitrogen) were combined and incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. Purified plasmid DNA (2 μg) or the equivalent volume of water (in the case of negative controls) was diluted in 250 μL of OptiMEM I, combined with the above lipofectamine-OptiMEM I mixture, and incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes. The entire sample was then added to a single well of a 2-well culture slide containing MN-1 cells. After a 4-hour incubation, the transfection medium was aspirated and replaced with normal growth medium. After a 48-hour incubation, slides were analyzed using an Olympus model IX71 fluorescence microscope equipped (Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA) with an F-View II digital camera (Olympus) using MicroSuite FIVE software (Olympus). The ES cell-derived motor neurons were prepared and differentiated as previously described and generously provided by Dr. Prabakaran Soundararajan (Soundararajan et al., 2006; Wichterle et al., 2002). Immunofluorescence was performed on fixed cells using anti-GARS and anti-GFP antibodies ((Nangle et al., 2007) and Abcam ab1218 respectively).

Yeast complementation

The yeast strain RJT3/II-1 [his3del200, leu2del1, ura3-52, grs1::HIS3; maintained by a GRS1-containing centromere vector bearing URA3 (Turner et al., 2000)] is devoid of an endogenous GRS1 locus, which was deleted via a recombination with a HIS3-containing cassette containing sequences that flank GRS1 in the yeast genome. This strain was transformed with pRS315 constructs containing wild-type GRS1, mutant GRS1, or no insert. To test each mutation, we modeled L129P, P234KY, G240R, G598A GARS at the orthologous amino acid in GRS1. Constructs were generated as previously described (Antonellis et al., 2006). Briefly, lithium acetate transformations were performed at 30°C using 200 ng of plasmid DNA. Transformation reactions were plated on yeast medium lacking uracil and leucine, and the resulting colonies were tested by PCR using primers specific to GRS1 and pRS315. For each transformation, 2 colonies found to carry the appropriate construct were selected for further analysis. Each colony was then inoculated into 2 ml of yeast medium lacking uracil and leucine, and incubated shaking at 30°C for 18 hours. Culture dilutions (1:1, 1:5, 1:10, and 1:125) were generated in YPD (Qbiogene, Irvine, CA), spotted on growth medium containing 0.1% 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA, Teknova, Hollister, CA), and incubated at 30°C for 2 days. Growth was assessed by visual inspection.

Results

Peripheral Neuropathy Versus Purkinje Cell Loss in Aarssti/sti and GarsNmf249/+ Mice

To compare the pathogenic mechanisms of mutations in Aars and Gars and to determine if mischarging of tRNAAla can lead to peripheral neuropathy, we first compared the phenotypes in cell populations affected by each mouse mutation. As previously described, GarsNmf249/+ mice have overt neuromuscular dysfunction and peripheral neuropathy beginning at 2–3 weeks of age (Seburn et al., 2006). In contrast, Aarssti/sti mice have ataxia and cerebellar Purkinje cell death caused by protein misfolding, but peripheral axons were not examined, although dominant mutations in human AARS were recently shown to cause an axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (Latour et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2006). We therefore examined the femoral nerves and neuromuscular junctions of Aarssti/sti mice to look for signs of peripheral neuropathy. There was no decrease in axon number in the motor branch of the femoral nerve, even at 14 months of age (Figure 1A-C, 540±40, 521±36 and 590±54 in control, young Aarssti/sti, and old Aarssti/sti mice respectively). Similarly, there was no defect in NMJ morphology or motor nerve terminal occupancy in the gastrocnemius, with the nerve terminal completely overlapping the field of postsynaptic acetylcholine receptors (Figure 1D,E). The apparent decrease in overall cross-sectional area of the nerve (Figure 1A,B) is consistent with a significant, uniform decrease in axon diameter, but no change in the G-ratio (a comparison of axon diameter to myelin thickness). The decreased nerve diameters correlate with a general decrease in body size (at least 20% decrease in body weight) in the Aarssti/sti mice. Therefore, the Aarssti/sti mice do not develop a peripheral neuropathy phenotype, even at ages when the loss of Purkinje cells in the cerebellum is nearly complete.

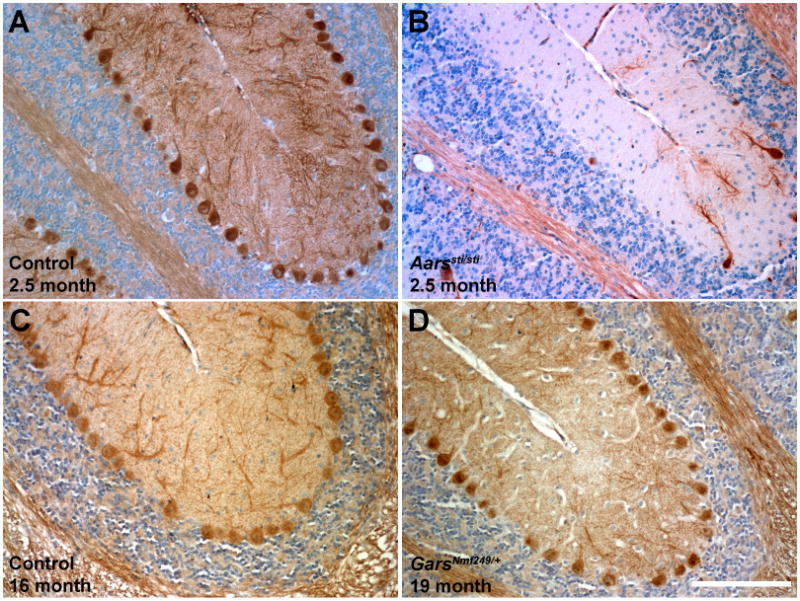

We next asked whether GarsNmf249/+ mice develop Purkinje cell degeneration as the Aarssti/sti mice do (Lee et al., 2006). No Purkinje cell loss was evident, even in mice 1.5 years old (Figure 2). To have the greatest probability of finding cell loss, very old mice from the GarsNmf249/+ colony were examined. Therefore, Aarssti/sti and GarsNmf249/+ appear to affect different cell populations.

Figure 2.

Cerebellar Purkinje cells persist in GarsNmf249/+ mice. Cerebellar Purkinje cells were stained with anti-calbindin in control (A, C), Aarssti/sti (B), and GarsNmf249/+ (D) mice. Purkinje cell loss is almost complete in Aarssti/sti by 2.5 months of age, but is not seen in GarsNmf249/+ mice, even at 1.5 years of age. All images are from a similar region of the base of the rostral folia (3 and 4) of the cerebellum. Scale bar in D = 145 μm.

No Evidence of Misfolded Proteins in GarsNmf249/+

Since amino acid misincorporation leads to ubiquitination of misfolded proteins, we examined the GarsNmf249/+ mice for ubiquitination in the spinal cord and cerebellum (Lee et al., 2006). Purkinje cells in the Aarssti/sti mice have marked cytoplasmic ubiquitin at 4 weeks of age, prior to cell loss (Figure 3A,B). No ubiquitin-positive inclusions were evident in Purkinje cells in the GarsNmf249/+ mice at 1 month, or even at 1.5 years (Figure 3C,D). Similarly, the spinal cord motor neurons of aged GarsNmf249/+ mice were also free of ubiquitin puncta (Figure 3E,F). The Aarssti/sti mice had some ubiquitin accumulation in the spinal cord as well as the cerebellum (not shown), consistent with their general increase in misfolded protein, but this does not lead to motor neuron loss or axonopathy. Therefore, it appears that the mechanism of pathogenesis in the GarsNmf249/+ mice is inconsistent with an accumulation of mutant GARS proteins or an accumulation of other neuronal proteins due to random misincorporation of amino acids through mischarging of tRNAGly by mutant GARS. Furthermore, the absence of ubiquitin staining in the GarsNmf249/+ brain and spinal cord suggests that there is no pathological aggregation of GARS or other misfolded proteins. A mouse model of Aars that causes peripheral neuropathy is not yet available, but the recessive Aarssti mouse does not show peripheral neuropathy, suggesting that the defect in the editing domain is distinct from the dominant mutation in the catalytic domain seen in CMT patients.

Effects of Wlds on the GarsNmf249/+ phenotype

The Wallerian Degeneration Slow (Wlds) mutation is a spontaneous mutation in mice resulting in the fusion of nicotinamide nucleotide adenylyltransferase 1 (Nmnat1), and ubiquitination factor E4B (Ube4b) (Coleman et al., 1998). This rearrangement slows Wallerian degeneration of axons following injury and preserves axons in a number of genetic models (Ferri et al., 2003; Mack et al., 2001; Mi et al., 2005). The mechanism underlying the axonal preservation is proposed to depend on overexpression of the Nmnat1 portion of the locus, and NMNAT may be serving as a chaperone to decrease protein misfolding or to decrease reactive oxygen species, preventing mitochondrial dysfunction (Press and Milbrandt, 2008; Zhai et al., 2006; Zhai et al., 2008). We therefore tested the ability of Wlds to preserve peripheral axons in the GarsNmf249/+ mice. No rescue of the axonal phenotype was seen at 4 weeks of age. Neuromuscular junctions from the gastrocnemius were similar between GarsNmf249/+; Wlds/+ and GarsNmf249/+ mice, with partial innervation by the motor nerve terminals and an immature morphology of the postsynaptic acetylcholine receptors (Figure 4A-C). The motor branch of the femoral nerve was also similarly reduced in size, and the large diameter myelinated axons were not present in either the GarsNmf249/+; Wlds or GarsNmf249/+ mice (Figure 4D-F). The number of axons was similar between GarsNmf249/+ (440 ± 14 from 6 mice) and GarsNmf249/+;Wlds (425 ± 13 from 4 mice, ttest p=0.39) mice, but was reduced compared to controls (561 ± 8 from 4 mice, ttest p<0.0001) (Figure 4G). Therefore, the Wlds mutation does not change the severity of the GarsNmf249/+ phenotype, further suggesting that the proposed chaperone and mitochondrial homoestatic mechanisms of Wlds are distinct from the pathogenic mechanism of Gars mutations.

Dendrite Morphology in GarsNmf249/+ mice

Neurons null for tRNA synthetases or other mutations that impair protein synthesis have defects in both axons and dendrites, as indicated by recent results in Drosophila (Chihara et al., 2007). We therefore examined the dendrites of motor neurons in the ventral horn of the spinal cord in GarsNmf249/+ mice using a Thy1-YFP-H transgenic strain to visualize a subset of motor neurons. We have not seen evidence of cell death or other pathology in the spinal cord of GarsNmf249/+ mice, although CMT patients with long-term, chronic neuropathy may lose neurons (Bird et al., 1997). In the mice, YFP+ cell bodies were readily found in the ventral horn of GarsNmf249/+ mice (4 mice examined, 4 weeks of age). These cells showed prominent dendritic arbors (Figure 5A,B), with an average of 5.0 ± 0.15 large, primary dendrites projecting from each soma (39 cells examined), which was the same as control (5.3 ± 0.26 from 32 control cells in 3 mice, Mann-Whitney rank sum test p= 0.36). The YFP+ cells were comparably abundant in the mutant and control spinal cord, consistent with previous studies that did not find a decrease in axon number in the ventral roots of mutant mice (Seburn et al., 2006). However, in the periphery, the number of YFP+ axons in wholemount preparations of sciatic nerve was greatly reduced, and no YFP+ NMJs were observed, suggesting the YFP+ cells constitute an affected motor neuron population (Figure 5C-F). We did not perform an extensive analysis of dendritic morphology, but dendrites were clearly not as adversely affected as axons. Thus, the motor neuron morphology defects in the GarsNmf249/+ mice are restricted to the axon, a phenotype that is inconsistent with the axonal and dendritic defects observed in Drosophila neurons with impaired protein synthesis.

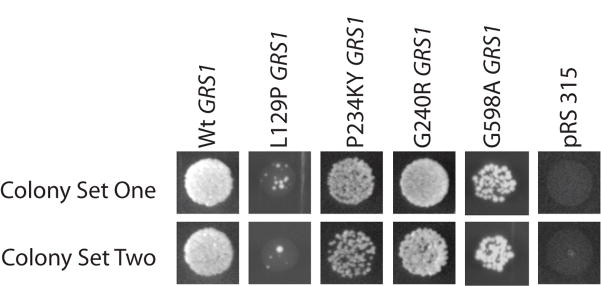

Yeast Complementation

We further examined the ability of the GarsNmf249 allele to support protein synthesis by performing complementation tests in yeast. The Nmf249 P to KY mutation was introduced into the yeast Gars ortholog GRS1 (P217 in yeast or P234 in human), and this construct was used to test complementation of the lethal phenotype associated with deletion of GRS1 (Antonellis et al., 2006). The mutant plasmid supported growth comparable to the wild type GRS1 sequence and to two CMT-causing GARS alleles (G240R and G598A; Figure 6). This is consistent with previous in vitro studies that did not detect a change in tRNA charging activity of the mutation (Seburn et al., 2006), but is in contrast to other GARS alleles (human L129P, H418R, and G526R), which fail to complement the GRS1 deletion (Antonellis et al., 2006). Thus, the P to KY mutation is capable of sustaining translation in yeast, as indicated by cell viability.

Figure 6.

The GARS P to KY mutation in yeast. The P to KY amino acid change (P234KY in human, P278KY in mouse) was introduced into the yeast homolog GRS1 at the conserved Proline 217, and used in complementation tests. GRS1 is a lethal mutation in yeast, but the P234KY GRS1 was capable of supporting growth comparable to a previously tested CMT-causing allele (G240R) and to an allele associated with the most severe patient phenotype reported to date (G598A GRS1). Therefore, the P234KY allele is capable of supporting translation. Two replica trials of each allele are shown and compared to the GRS1 mutant strain transfected with wild type GRS1, the previously-reported hypomorphic allele L129P GRS1, and the empty vector (lethal).

GARS Protein Localization

Altered subcellular protein localization has been reported for mutant forms of both GARS and YARS (Antonellis et al., 2006; Jordanova et al., 2006; Nangle et al., 2007). This was examined for the P to KY mutation found in the GarsNmf249 allele by introducing the mutation into the human coding sequence (P234KY) in frame with an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) tag, and transfecting immortalized motor neurons (MN-1 cells, Supp. Figure 1). In cells expressing wild type GARS-EGFP, the protein localized to cytoplasmic granules, and is also found in puncta in the extending processes of these cells. In contrast, P234KY GARS-EGFP was diffusely localized throughout the cytoplasm and processes and did not show any points of concentrated localization. The physiological significance of this altered localization is unclear, although it is a consistent result with many mutant forms of GARS (Antonellis et al., 2006; Nangle et al., 2007). We therefore examined cells with a better-defined motor neuron fate and without transfection and overexpression. Endogenous GARS protein labeled in motor neurons differentiated from ES cell cultures was not localized to cytoplasmic granules, although the pattern of intracellular staining was somewhat punctate (Figure 7A). The ES cells used were wild type except for an Hb9-driven GFP transgene that is a marker of motor neuron cell fates. Cells that were positive for GFP immunoreactivity (motor neurons) were not markedly different in their GARS staining intensity or localization from other cell types in the culture. In spinal cord and peripheral nerve samples derived from presumably unaffected human cadavers, wild-type GARS protein also localizes to granules (Antonellis et al., 2006). Spinal cord cross sections from wild type and GarsNmf249/+ mice were also stained with GARS antibodies and granules were seen in what appeared to be cell processes (Figure 7B, N=3 mice each genotype, 4 and 7 weeks of age). However, the number of granules was highly variable and did not correlate with age, sex, or genotype. Therefore, the significance of this staining pattern is unclear.

GARS localization was also examined in the cerebellum of GarsNmf249/+ and control mice (data not shown). Mutant and control samples showed generally the same pattern of staining. We noted a trend for brighter staining in the GarsNmf249/+ samples, and brighter staining in axon tracts than in cellular regions in both the cerebellum and spinal cord in both mutant and control samples. A trend for decreasing fluorescence intensity with age was also seen in comparing 4 week and 10 week-old samples of both genotypes. This general pattern of anti-GARS staining was preserved, even in mice of 1.5 years of age, in both wild type and GarsNmf249/+ samples (not shown), and whereas staining in the cerebellum tended to decrease in intensity with age, staining intensity in the spinal cord was constant.

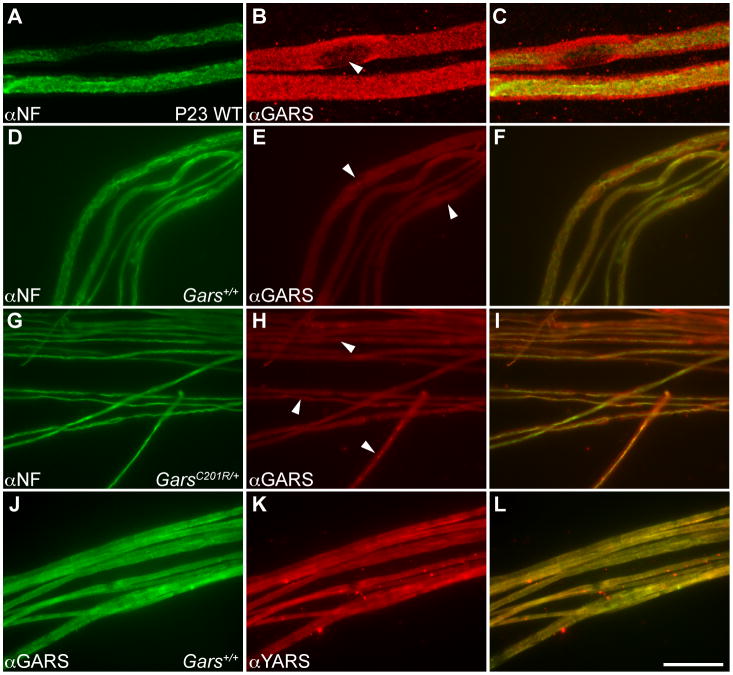

In light of the apparently axon-specific degeneration (Figure 5) caused by Gars mutations, and the axon pathology of DI-CMTC associated with human YARS mutations, we examined the localization of GARS and YARS in teased fiber preparations from mouse sciatic nerve. Staining wild type C57BL/6J mice at P23 demonstrated robust GARS immunoreactivity in both axons and Schwann cells (Figure 8A-C, N=5 mice, pattern was confirmed with two independent anti-GARS antibodies). The relative intensities of the Schwann cell versus axonal staining were variable, but generally close to equal. Large diameter fibers are more severely affected by the GarsNmf249 mutation and begin degenerating at approximately this age, but there was no correlation between axon diameter and GARS staining intensity (r=0.005). As anticipated, GARS was excluded from Schwann cell nuclei, but was present in the surrounding cytoplasm. Axons from mice carrying the milder GarsC201R/+ mutation were compared to wild type littermates to determine if the mutant protein is mislocalized (Figure 8D-I). The C201R allele was chosen because the axons are not as different in size and some larger diameter axons persist (N=3 C201R and 5 WT at P88, 2 C201R and 2 WT at P57). As at younger ages, GARS was present in the Schwann cells and axons of both wild type and GarsC201R/+ axons. Some apparent enrichment of the protein in a subset of axons was observed in one P88 mutant mouse (10 of 39 axons), but this effect was not generally observed (1 of 96 axons from the other two GarsC201R/+ P88 mice, and never in two GarsC201R/+ mice at P57, 3 of 140 axons in three wild type P88 mice). The GARS protein colocalized with YARS, which also was found in Schwann cells and axons in a pattern indistinguishable from GARS in both GarsC201R/+ and wild type nerves (Figure 8J-L). The localization of both GARS and YARS to peripheral axons and Schwann cells is consistent with the axon-specific pathology of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, but whether these proteins may be performing noncanonical functions, particularly in axons, is unknown.

Figure 8.

GARS and YARS in peripheral axons. A-C) Teased fibers from wild type P23 sciatic nerves were stained with anti-neurofilament (A) and anti-GARS (B) and visualized as projections of confocal Z-series. The merged image (C) demonstrates that both the axon and Schwann cells exhibit robust GARS staining. As anticipated, the protein is excluded from the Schwann cell nucleus (arrowhead in B), but is present in the cytoplasm. D-F) With standard fluorescence microscopy, three-month-old wild type mice had a similar staining pattern to P23 mice, nodes of Ranvier are denoted by the arrowheads in E. G-I) Three-month-old GarsC201R/+ littermates were also stained for neurofilament and GARS. In some axons, the GARS protein appears to be enriched in the axon in the mutant samples (arrowheads in H), but this was not a reproducible effect and was not observed in mutant axons at two months of age (not shown). J-L) Staining with GARS (J) and YARS (K) showed an identical pattern in peripheral nerves, demonstrated by the complete overlap of signals in the merged image (L). The scale bar in L represents 14 μm in A-C and 49 μm in D-L.

Discussion

We have tested several pathogenic mechanisms through which mutations in alanyl- and glycyl-tRNA synthetase may cause neurodegeneration and peripheral neuropathy. First, we tested whether amino acid misincorporation and accumulation of misfolded proteins arising from tRNA mischarging leads to peripheral axon defects. This was done in direct comparison of GarsNmf249/+ with Aarssti/sti mice, in which an editing domain mutation in AARS reduces translational fidelity (Lee et al., 2006). We saw no peripheral neuropathy in the Aarssti/sti mice, nor any Purkinje cell degeneration in the GarsNmf249/+ mice. Furthermore, we saw no increase in ubiquitin staining in either the brains or spinal cords of GarsNmf249/+ mice, whereas this is readily apparent in the Purkinje cells of Aarssti/sti mice prior to their degeneration. Next, we tested possible defects arising from insufficiencies in protein synthesis in GarsNmf249/+ mice. In contrast to Drosophila neurons lacking ARS activity, we observed no defects in dendrite morphology in ventral-horn motor neurons in the spinal cord (Chihara et al., 2007). Furthermore, the Nmf249 allele of Gars was able to complement yeast mutations in GRS1, the yeast glycyl tRNA synthetase ortholog. Both of these results are inconsistent with a profound defect in protein synthesis in vivo. Third, we examined GARS protein localization both in vitro and in wild type and Gars mutant mice. The mutant recombinant protein shows a diffuse cytoplasmic distribution in transfected MN-1 cells, whereas the wild type protein has punctate accumulations in the cell body and extending neurites. However, such puncta were not observed in ES cell-derived wild type motor neurons, and the pattern of GARS immunoreactivity was not changed in the central nervous system or peripheral nerves of Gars mutant mice. Both GARS and YARS localized to peripheral axons and Schwann cells in mouse sciatic nerve.

Each of these experiments tested a proposed pathogenic mechanism for ARS mutations, and their interpretation and implications for these mechanisms are discussed below.

Amino Acid Misincorporation and Protein Misfolding

The neurodegeneration of the Aarssti/sti mice is consistent with amino acid misincorporation and this is a proposed mechanism for AARSR329H mutation causing CMT (Latour et al., 2010). The sticky mutation is in the editing domain of the AARS enzyme and the active site of AARS allows both glycine and serine, in addition to alanine, to be charged onto tRNAala, though less well than alanine itself (Lee et al., 2006). The role of the editing domain is to correct these misacylations, repressing the rate of mischarging from 1 in 400, as predicted from the energetics of the enzymatic reaction, to 1 in 3000-10,000 (Jakubowski and Goldman, 1992; Loftfield and Vanderjagt, 1972). Indeed, primary embryonic fibroblasts (MEFS) from Aarssti/sti mice are sensitive to high concentrations of serine in culture, and the nervous system of Aarssti/sti mice show signs of misfolded protein responses. Although the sticky mutation is a subtle change in editing function, this may correlate well with the recessive, degenerative phenotype. More dramatic changes in editing activity in valyl-tRNA sythetase (VARS) lead to rapid apoptosis of mammalian cells in culture and may therefore prove to be lethal in mice or humans (Nangle et al., 2006). Presumably, the Aarssti mutation is recessive due to a threshold effect for levels of protein misfolding, and more severe editing mutations may result in phenotypes even in heterozygous mice.

In contrast, GARS does not have an editing domain. The active site of the wild type enzyme is sterically constrained and can only accept glycine, the smallest amino acid (Arnez et al., 1999). For Gars mutations to lead to misacylation, the structure of the active site would have to be affected, opening it so other amino acids could fit; but if this were true, the enzyme would have no ability to correct mistakes, as there is no editing function. The structure of the GARS enzyme predicts that only a few alleles will alter the active site structure (G526 and E71), whereas most affect the dimer interface, sometimes acting at a distance, and these typically lead to a decrease or loss in enzymatic activity (Nangle et al., 2007; Xie et al., 2007). However, other mutations in which changes in the amino acid substrate specificity of an enzyme lead to neuro toxic effects are documented. For example, mutations in the SPTLC1 subunit of Serine Palmitoyltransferase lead to Hereditary Sensory and Autonomic Neuropathy 1 (HSAN1) because glycine and alanine are mistakenly condensed onto palmitoyl-CoA leading to an accumulation of toxic deoxysphygoid bases (Eichler et al., 2009; Penno et al., 2010).

Mischarging of tRNAs was tested in vitro by our collaborators, Drs. Paul Schimmel and Leslie Nangle of The Scripps Research Institute (personal communication). In a pyrophosphate release assay that measures the first step in amino acylation, mutant forms of GARS showed only background activity in the presence of other amino acids, whereas they were active in the presence of glycine. However, these are challenging assays, and a negative result in vitro may not be definitive. We therefore felt it was important to examine the possibility of amino acid misincorporation in vivo.

The differences in phenotype between Aarssti/sti and GarsNmf249/+ suggest the mutations cause distinct neurodegenerative conditions. The lack of ubiquitin accumulation in GarsNmf249/+ mice, even in aged motor neurons, also argues against significant levels of misfolded proteins arising from misacylation, or the formation of aggregates of GARS or other proteins. Furthermore, the proposed function of Wlds as a chaperone protein would also predict that the Gars phenotype would be suppressed if protein misfolding were indeed the underlying mechanism (Zhai et al., 2008). This absence of protein misfolding sets GARS mutations and CMT2D apart from other motor neuron diseases such as SOD1-mediated ALS, in which SOD1 itself is misfolded and found in aggregates and there is a general increase in ubiquitin labeling in tissue. These results, taken with the considerations of biochemistry and structural biology, lead us to conclude that the GarsNmf249 mutation is not causing peripheral neuropathy through the misincorporation of amino acids during translation. Also, we conclude that the amino acid misincorporation demonstrated in Aarssti/sti mice does not lead to peripheral neuropathy, suggesting a different mechanism for the dominant human disease-associated AARS allele.

Insufficient protein synthesis

Our hypothesis that the peripheral neuropathy of GarsNmf249/+ may arise from insufficiencies in protein synthesis was based in part on results from Drosophila (Chihara et al., 2007). In flies, clonal patches of Gars-null neurons were generated using the mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM) system (Lee et al., 2000). In these patches, neurons had retracted axons and dendrites. Homozygous Gars-null cells should be incapable of translation, and consistent with this mechanism underlying the morphological changes, other Drosophila mutations that eliminate protein synthesis had a similar phenotype. Interestingly, impeded cytoplasmic protein synthesis affected both dendrites and axons whereas dendrites were more affected when mitochondrial protein synthesis was selectively eliminated. Also, the maintenance of dendritic arbors required Gars while the axons were affected at earlier stages of outgrowth. These Drosophila phenotypes are caused by loss-of-function recessive mutations, and while they caused changes in neurite (axon and dendrite) morphology, it is unclear if they represent a Charcot-Marie-Tooth phenotype, in which the mutations are dominant and affects have only been described in axons. Our examination of the dendrites of motor neuron dendrites in the spinal cord suggests that the CMT-phenotype of the GarsNmf249/+ mice is indeed restricted to the axon, in contrast to the findings from null mutant cells in flies. It is possible that by selecting for Thy1-YFP-H positive cells we inadvertently selected a healthy population. However, we have previously shown that there is no reduction in axon number in the ventral roots, nor any pathology in the spinal cord, suggesting that there was no loss of cells in the spinal cord (Seburn et al., 2006). In CMT patients, chronic neuropathy can lead to neuronal loss (Bird et al., 1997), and such phenotypes may eventually arise in mice if aged beyond 1.5 years. The reduction of YFP-positive axons in the peripheral nerve and high percentage of dysmorphic motor nerve terminals in the mutant muscle argue that it is unlikely that all motor neurons in the spinal cord would look normal if a dendritic phenotype was at all comparable in severity to the axonal defects.

Furthermore, the P to KY mutation of the GarsNmf249/+ mutant enzyme is capable of rescuing yeast GRS1 mutations, indicating it is functional and sufficient for protein synthesis in the context of a yeast cell. This is consistent with the mutation not reducing in vitro enzymatic activity (Seburn et al., 2006). Other alleles of GARS do show reduced activity, and these alleles also fail to complement the yeast mutations (Antonellis et al., 2006). The exception to this is the G240R allele, which is reported to have reduced activity because of impaired dimerization, but is capable of rescuing GRS1 mutations when introduced into the yeast sequence (Antonellis et al., 2006; Nangle et al., 2007). However, all of these alleles cause a similar neuropathy, complicating the correlation between the phenotype and the loss of known enzymatic function. Indeed, G598A GARS is associated with the most severe phenotype reported to date (James et al., 2006). While the effect of this mutation on tRNA charging has not been assessed, we show here that this mutation is also able to complement deletion of yeast GRS1. Therefore, it is possible that some of these mutations do cause a peripheral neuropathy through their effects on GARS tRNA charging activity, but this would require that other alleles cause the same phenotype through other mechanisms. This seems unlikely, and we therefore conclude that generalized defects in protein synthesis are unlikely to be a common mechanism for Gars mutations, and any such effects would instead have to be occurring in a specific subcellular compartment such as the axon. However, the recently identified patient with compound heterozygous mutations in KARS would also suggest that loss-of-function could be contributing to the axonal neuropathy phenotype, as well as the more severe generalized neurological presentation.

Changes in Protein Localization

Mutant forms of both YARS and GARS have altered subcellular localization in transfected cells, and this could provide an alternative mechanism for cellular loss of function, even when enzymatic activity is retained. When transfected into neuroblastoma cell lines, wild type YARS localizes to the tips of outgrowing protrusions in differentiating cells. The mutant forms of YARS that cause DI-CMTC maintain a diffuse cytoplasmic localization in these cells (Jordanova et al., 2006). Similar results were obtained transfecting wild type and CMT2D-causing alleles of human GARS (Antonellis et al., 2006; Nangle et al., 2007), and we show here that GARS carrying the human equivalent of the mouse allele (P234KY) also has diffuse cytoplasmic localization. Furthermore, GARS antibodies label cytoplasmic granules in human peripheral nerve and spinal cord samples (Antonellis et al., 2006). We did not observe a change in granules in the spinal cord of the GarsNmf249/+ mice, or the formation of granules of endogenous GARS in cultured ES cell-derived motor neurons.

The localization of both GARS and YARS to peripheral axons and Schwann cells is consistent with the axon specific pathology caused by mutations in these genes. The presence of ARS in the cytoplasm of Schwann cells is not unexpected, as this is the site of translation in these cells. However, the significance of the wide spread distribution of GARS and YARS in Schwann cells and the localization of these proteins in axons is unclear. This distribution may suggest axonal functions of GARS and YARS in the adult. The occurrence of axonal translation in adult vertebrates is gaining acceptance, but is still poorly understood (Giuditta et al., 2008; Lin and Holt, 2008; Wang et al., 2007), again calling into question whether ARSs localized to axons are functioning in protein synthesis, or whether they may have an unknown, noncanonical activity. A failure of a maintenance level of translation in adult steady-state axons is an unorthodox proposal, but it would provide a disease mechanism that is easy to reconcile with GARS-associated CMT2D and other axonal neuropathies cause by ARS genes.

Summary and Conclusions

We are now able to exclude some previous hypotheses concerning how ARS mutations cause peripheral neuropathy, and also develop new ones. First, misacylation of tRNAs leading to misfolded proteins appears to be the mechanism underlying the cerebellar neurodegeneration in the Aarssti mutation, but it does not lead to a peripheral neuropathy. There is no evidence for such a mechanism underlying the GarsNmf249/+phenoytpe. There is also no evidence to suggest a general insufficiency in protein synthesis as the mechanism underlying the GarsNmf249 allele, unless such a defect arose in a specific subcellular compartment, most likely the axon. The P to KY mutant form of GARS did indeed mislocalize in vitro, and the protein is present in axons and Schwann cells in vivo. However, the GARS protein does not appear to be redistributed in the Gars mutant mice at the resolution by which we can analyze it with immunocytochemistry and with the limitation of examining heterozygous mice, which may make a change in localization less obvious. The presence of GARS and YARS in axon tracts and peripheral nerves of adult mice may suggest a non-canonical function in that cellular compartment given the general lack of other protein synthesis machinery in adult vertebrate axons, or it may be revealing a greater role for axonal translation in adults than previously anticipated. Alternatively, the mutant forms of the protein may be adopting a novel pathological function unrelated to the known activity of GARS.

Supplementary Material

GARS transfection in MN1 cells. A) In transfected MN-1 cells, wild type GARS is found in punctate structures in the cell body and in outgrowing processes. B) GARS carrying the P234KY mutation is found diffusely throughout the cell. The scale bar is 12.5 μm for A,B.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Greg Cox for comments on the manuscript, and members of the Ackerman and Burgess labs for discussion, reagents, and animal husbandry. We would also like to thank the scientific services at The Jackson Laboratory, particularly Pete Finger and the Histology and Microscopy service, as well as Dr. Eric Green for wild-type GARS constructs, Dr. Prabakaran Soundararajan for differentiated ES cell cultures, Drs. Pat Nolan and Elizabeth Fisher for providing the GarsC201R mice, and Drs. Paul Schimmel and Leslie Nangle for the RJT3/II-1 yeast strain, the anti-GARS anti serum, and communication of unpublished data. The Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank provided reagents for these studies. S.L.A. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. This work was supported by the Fondation pour la Recherche Medicale, France, to M.S., the National Institutes of Health [NS054154 to R.W.B., NS060983 to A.A., NS042613 to S.L.A.], and the Amyotropic Lateral Sclerosis Association to K.L.S. The Scientific Services at The Jackson Laboratory are supported by the NCI Cancer Center CA034196.

Abbreviations

- ARS

aminoacyl tRNA synthetase

- GARS

glycyl-tRNA synthetase

- YARS

tyrosyl tRNA synthetase

- AARS

alanyl tRNA synthetase

- CMT

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease

- Wlds

Wallerian degeneration slow

- HSMN

hereditary sensory and motor neuropathy

- DI-CMTC

dominant intermediate Charcot-Marie-Tooth type C

- CMT2D

Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 2D

- CAST

Castaneus

- YFP

yellow fluorescent protein

- WT

wild type

- ES

embryonic stem cell

- P#

postnatal age in days

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Achilli F, Bros-Facer V, Williams HP, Banks GT, Alqatari M, Chia R, Tucci V, Groves M, Nickols CD, Seburn KL, Kendall R, Cader MZ, Talbot K, van Minnen J, Burgess RW, Brandner S, Martin JE, Koltzenburg M, Greensmith L, Nolan PM, Fisher EM. An ENU-induced mutation in mouse glycyl-tRNA synthetase (GARS) causes peripheral sensory and motor phenotypes creating a model of Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 2D peripheral neuropathy. Disease models & mechanisms. 2009 doi: 10.1242/dmm.002527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonellis A, Ellsworth RE, Sambuughin N, Puls I, Abel A, Lee-Lin SQ, Jordanova A, Kremensky I, Christodoulou K, Middleton LT, Sivakumar K, Ionasescu V, Funalot B, Vance JM, Goldfarb LG, Fischbeck KH, Green ED. Glycyl tRNA synthetase mutations in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2D and distal spinal muscular atrophy type V. American journal of human genetics. 2003;72:1293–1299. doi: 10.1086/375039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonellis A, Green ED. The role of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases in genetic diseases. Annual review of genomics and human genetics. 2008;9:87–107. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonellis A, Lee-Lin SQ, Wasterlain A, Leo P, Quezado M, Goldfarb LG, Myung K, Burgess S, Fischbeck KH, Green ED. Functional analyses of glycyl-tRNA synthetase mutations suggest a key role for tRNA-charging enzymes in peripheral axons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10397–10406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1671-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnez JG, Dock-Bregeon AC, Moras D. Glycyl-tRNA synthetase uses a negatively charged pit for specific recognition and activation of glycine. Journal of molecular biology. 1999;286:1449–1459. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo EJ, Sirkowski EE, Chitale R, Scherer SS. Acute demyelination disrupts the molecular organization of peripheral nervous system nodes. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2004;479:424–434. doi: 10.1002/cne.20321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe K, Mock M, Merriman E, Schimmel P. Distinct domains of tRNA synthetase recognize the same base pair. Nature. 2008;451:90–93. doi: 10.1038/nature06454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird TD, Kraft GH, Lipe HP, Kenney KL, Sumi SM. Clinical and pathological phenotype of the original family with Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 1B: a 20-year study. Annals of neurology. 1997;41:463–469. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chihara T, Luginbuhl D, Luo L. Cytoplasmic and mitochondrial protein translation in axonal and dendritic terminal arborization. Nature neuroscience. 2007;10:828–837. doi: 10.1038/nn1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman MP, Conforti L, Buckmaster EA, Tarlton A, Ewing RM, Brown MC, Lyon MF, Perry VH. An 85-kb tandem triplication in the slow Wallerian degeneration (Wlds) mouse. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:9985–9990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edvardson S, Shaag A, Kolesnikova O, Gomori JM, Tarassov I, Einbinder T, Saada A, Elpeleg O. Deleterious mutation in the mitochondrial arginyl-transfer RNA synthetase gene is associated with pontocerebellar hypoplasia. American journal of human genetics. 2007;81:857–862. doi: 10.1086/521227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler FS, Hornemann T, McCampbell A, Kuljis D, Penno A, Vardeh D, Tamrazian E, Garofalo K, Lee HJ, Kini L, Selig M, Frosch M, Gable K, von Eckardstein A, Woolf CJ, Guan G, Harmon JM, Dunn TM, Brown RH., Jr Overexpression of the wild-type SPT1 subunit lowers desoxysphingolipid levels and rescues the phenotype of HSAN1. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14646–14651. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2536-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri A, Sanes JR, Coleman MP, Cunningham JM, Kato AC. Inhibiting axon degeneration and synapse loss attenuates apoptosis and disease progression in a mouse model of motoneuron disease. Curr Biol. 2003;13:669–673. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuditta A, Chun JT, Eyman M, Cefaliello C, Bruno AP, Crispino M. Local gene expression in axons and nerve endings: the glia-neuron unit. Physiological reviews. 2008;88:515–555. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00051.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M, Chong YE, Beebe K, Shapiro R, Yang XL, Schimmel P. The C-Ala domain brings together editing and aminoacylation functions on one tRNA. Science (New York, NY) 2009;325:744–747. doi: 10.1126/science.1174343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibba M, Soll D. Aminoacyl-tRNAs: setting the limits of the genetic code. Genes & development. 2004;18:731–738. doi: 10.1101/gad.1187404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isohanni P, Linnankivi T, Buzkova J, Lonnqvist T, Pihko H, Valanne L, Tienari PJ, Elovaara I, Pirttila T, Reunanen M, Koivisto K, Marjavaara S, Suomalainen A. DARS2 mutations in mitochondrial leucoencephalopathy and multiple sclerosis. Journal of medical genetics. 2010;47:66–70. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.068221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski H, Goldman E. Editing of errors in selection of amino acids for protein synthesis. Microbiological reviews. 1992;56:412–429. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.3.412-429.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James PA, Cader MZ, Muntoni F, Childs AM, Crow YJ, Talbot K. Severe childhood SMA and axonal CMT due to anticodon binding domain mutations in the GARS gene. Neurology. 2006;67:1710–1712. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000242619.52335.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordanova A, Irobi J, Thomas FP, Van Dijck P, Meerschaert K, Dewil M, Dierick I, Jacobs A, De Vriendt E, Guergueltcheva V, Rao CV, Tournev I, Gondim FA, D'Hooghe M, Van Gerwen V, Callaerts P, Van Den Bosch L, Timmermans JP, Robberecht W, Gettemans J, Thevelein JM, De Jonghe P, Kremensky I, Timmerman V. Disrupted function and axonal distribution of mutant tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase in dominant intermediate Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. Nature genetics. 2006;38:197–202. doi: 10.1038/ng1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latour P, Thauvin-Robinet C, Baudelet-Mery C, Soichot P, Cusin V, Faivre L, Locatelli MC, Mayencon M, Sarcey A, Broussolle E, Camu W, David A, Rousson R. A Major Determinant for Binding and Aminoacylation of tRNA(Ala) in Cytoplasmic Alanyl-tRNA Synthetase Is Mutated in Dominant Axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. American journal of human genetics. 2010;86:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Beebe K, Nangle LA, Jang J, Longo-Guess CM, Cook SA, Davisson MT, Sundberg JP, Schimmel P, Ackerman SL. Editing-defective tRNA synthetase causes protein misfolding and neurodegeneration. Nature. 2006;443:50–55. doi: 10.1038/nature05096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T, Winter C, Marticke SS, Lee A, Luo L. Essential roles of Drosophila RhoA in the regulation of neuroblast proliferation and dendritic but not axonal morphogenesis. Neuron. 2000;25:307–316. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80896-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin AC, Holt CE. Function and regulation of local axonal translation. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2008;18:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftfield RB, Vanderjagt D. The frequency of errors in protein biosynthesis. The Biochemical journal. 1972;128:1353–1356. doi: 10.1042/bj1281353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan DT, Mazauric MH, Kern D, Moras D. Crystal structure of glycyl-tRNA synthetase from Thermus thermophilus. Embo J. 1995;14:4156–4167. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack TG, Reiner M, Beirowski B, Mi W, Emanuelli M, Wagner D, Thomson D, Gillingwater T, Court F, Conforti L, Fernando FS, Tarlton A, Andressen C, Addicks K, Magni G, Ribchester RR, Perry VH, Coleman MP. Wallerian degeneration of injured axons and synapses is delayed by a Ube4b/Nmnat chimeric gene. Nature neuroscience. 2001;4:1199–1206. doi: 10.1038/nn770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin HM, Sakaguchi R, Liu C, Igarashi T, Pehlivan D, Chu K, Iyer R, Cruz P, Cherukuri PF, Hansen NF, Mullikin JC, Biesecker LG, Wilson TE, Ionasescu V, Nicholson G, Searby C, Talbot K, Vance JM, Zuchner S, Szigeti K, Lupski JR, Hou YM, Green ED, Antonellis A. Compound heterozygosity for loss-of-function lysyl-tRNA synthetase mutations in a patient with peripheral neuropathy. American journal of human genetics. 2010;87:560–566. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi W, Beirowski B, Gillingwater TH, Adalbert R, Wagner D, Grumme D, Osaka H, Conforti L, Arnhold S, Addicks K, Wada K, Ribchester RR, Coleman MP. The slow Wallerian degeneration gene, WldS, inhibits axonal spheroid pathology in gracile axonal dystrophy mice. Brain. 2005;128:405–416. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motley WW, Talbot K, Fischbeck KH. GARS axonopathy: not every neuron's cup of tRNA. Trends in neurosciences. 2010;33:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nangle LA, Motta CM, Schimmel P. Global effects of mistranslation from an editing defect in mammalian cells. Chem Biol. 2006;13:1091–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nangle LA, Zhang W, Xie W, Yang XL, Schimmel P. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease-associated mutant tRNA synthetases linked to altered dimer interface and neurite distribution defect. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:11239–11244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705055104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penno A, Reilly MM, Houlden H, Laura M, Rentsch K, Niederkofler V, Stoeckli ET, Nicholson G, Eichler F, Brown RH, Jr, von Eckardstein A, Hornemann T. Hereditary sensory neuropathy type 1 is caused by the accumulation of two neurotoxic sphingolipids. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:11178–11187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.092973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press C, Milbrandt J. Nmnat delays axonal degeneration caused by mitochondrial and oxidative stress. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4861–4871. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0525-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar-Grueso EF, Kim S, Kim H. Embryonic mouse spinal cord motor neuron hybrid cells. Neuroreport. 1991;2:505–508. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199109000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheper GC, van der Klok T, van Andel RJ, van Berkel CG, Sissler M, Smet J, Muravina TI, Serkov SV, Uziel G, Bugiani M, Schiffmann R, Krageloh-Mann I, Smeitink JA, Florentz C, Van Coster R, Pronk JC, van der Knaap MS. Mitochondrial aspartyl-tRNA synthetase deficiency causes leukoencephalopathy with brain stem and spinal cord involvement and lactate elevation. Nature genetics. 2007;39:534–539. doi: 10.1038/ng2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmel P. Development of tRNA synthetases and connection to genetic code and disease. Protein Sci. 2008;17:1643–1652. doi: 10.1110/ps.037242.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seburn KL, Nangle LA, Cox GA, Schimmel P, Burgess RW. An active dominant mutation of glycyl-tRNA synthetase causes neuropathy in a Charcot-Marie-Tooth 2D mouse model. Neuron. 2006;51:715–726. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soundararajan P, Miles GB, Rubin LL, Brownstone RM, Rafuse VF. Motoneurons derived from embryonic stem cells express transcription factors and develop phenotypes characteristic of medial motor column neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3256–3268. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5537-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storkebaum E, Leitao-Goncalves R, Godenschwege T, Nangle L, Mejia M, Bosmans I, Ooms T, Jacobs A, Van Dijck P, Yang XL, Schimmel P, Norga K, Timmerman V, Callaerts P, Jordanova A. Dominant mutations in the tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase gene recapitulate in Drosophila features of human Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:11782–11787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905339106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, van Niekerk E, Willis DE, Twiss JL. RNA transport and localized protein synthesis in neurological disorders and neural repair. Developmental neurobiology. 2007;67:1166–1182. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichterle H, Lieberam I, Porter JA, Jessell TM. Directed differentiation of embryonic stem cells into motor neurons. Cell. 2002;110:385–397. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00835-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W, Nangle LA, Zhang W, Schimmel P, Yang XL. Long-range structural effects of a Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease-causing mutation in human glycyl-tRNA synthetase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:9976–9981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703908104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai RG, Cao Y, Hiesinger PR, Zhou Y, Mehta SQ, Schulze KL, Verstreken P, Bellen HJ. Drosophila NMNAT maintains neural integrity independent of its NAD synthesis activity. PLoS biology. 2006;4:e416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai RG, Zhang F, Hiesinger PR, Cao Y, Haueter CM, Bellen HJ. NAD synthase NMNAT acts as a chaperone to protect against neurodegeneration. Nature. 2008;452:887–891. doi: 10.1038/nature06721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

GARS transfection in MN1 cells. A) In transfected MN-1 cells, wild type GARS is found in punctate structures in the cell body and in outgrowing processes. B) GARS carrying the P234KY mutation is found diffusely throughout the cell. The scale bar is 12.5 μm for A,B.