Abstract

Objective

This study was undertaken to determine whether there is familial aggregation of Hyperemesis Gravidarum making it a disease amenable to genetic study.

Study Design

Cases with severe nausea and vomiting in a singleton pregnancy treated with intravenous hydration and unaffected friend controls completed a survey regarding family history.

Results

Sisters of women with Hyperemesis Gravidarum have a significantly increased risk of having Hyperemesis Gravidarum themselves (OR=17.3, p=0.005). Cases have a significantly increased risk of having a mother with severe nausea and vomiting; 33% of cases reported an affected mother compared to 7.7% of controls (p<.0001). Cases reported a similar frequency of affected second-degree maternal and paternal relatives (18% maternal lineage, 23% paternal lineage).

Conclusion

There is familial aggregation of Hyperemesis Gravidarum. This study provides strong evidence for a genetic component to hyperemesis gravidarum. Identification of the predisposing gene(s) may determine the cause of this poorly understood disease of pregnancy.

Keywords: Familial Aggregation, Genetic, Hyperemesis Gravidarum, Nausea, Pregnancy

1. Introduction

Hyperemesis gravidarum (HG), severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy, hospitalizes more than 59,000 pregnant women in the U.S. annually, with most authors reporting an incidence of 0.5% [1,2]. Estimates of severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy vary greatly and range from 0.3% in a Swedish registry to as high as 10.8% in a Chinese registry of pregnant women [3,4]. Recent large population studies support ethnic variation in the incidence of HG. A Norwegian Study of the medical birth registry of Norway from 1967 to 2005, defined HG as persistent nausea and vomiting in pregnancy associated with ketosis and weight loss >5% of pre-pregnancy weight, and revealed an overall prevalence of 0.9%, but when broken down by ethnicity, found HG in 2.2% of 3927 Pakistani women and 1.9% of 1997 Turkish women, both more than twice the incidence of 0.9% in 798,311 Norwegian women [5]. A study of California birth and death certificates after 20 weeks gestation linked to neonatal hospital discharge data in 1999 with the primary diagnosis of hyperemesis found an incidence 0.5% (2466 cases out of 520,739 births), and women with HG were reportedly significantly less likely to be white or hispanic compared to non-whites or non-hispanics [6]. A Canadian study found HG in 1270 (0.8%) out of 156,091 of women with singleton deliveries between 1988 and 2002 [7]. This rate was confirmed in a second Canadian study during the same timeframe of the population-based Nova Scotia Atlee Perinatal Database of deliveries at 20 weeks gestation, that found HG in 1301 (0.8%) out of 157,922 pregnancies [8]. Asian populations tend to have higher incidence rates. For example, a Malaysian study identified 192 recorded cases (3.9%) out of 4937 maternities [9]. Additionally, a study of 3350 singleton deliveries in an Eastern Asian population observed HG in 119 (3.6%) of the population [10]. As mentioned, a study of 1867 singleton live births revealed the highest rate of severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy in Shanghai, China, from 1986 to 1987, with an incidence of 10.8%. However, unlike the other studies mentioned, this study was based on a clinical record of severe vomiting on prenatal care cards, rather than hospitalization for HG, did not limit itself to a primary diagnosis of HG and included, for example, women with chronic liver disease, chronic hypertension, chronic renal illness, and preeclampsia [4]. Hyperemesis gravidarum is the most common cause of hospitalization in the first half of pregnancy and is second only to preterm labor for pregnancy overall [11]. HG can be associated with serious maternal and fetal morbidity such as Wernicke’s encephalopathy [12], fetal growth restriction, and even maternal and fetal death [6,13].

A biologic component to the condition has been suggested from animal studies. Anorexia of early pregnancy has been observed in various mammals including monkeys [14]. In dogs, anorexia can be accompanied by vomiting and can be severe enough to require pregnancy termination [15]. Several lines of evidence support a genetic predisposition to nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (NVP). Firstly, in the only study of NVP in twins, concordance rates were more than twice as high for monozygotic compared to dizygotic twins [16]. Secondly, several investigators have noted that siblings and mothers of patients affected with NVP and HG are more likely to be affected than siblings and mothers of unaffected individuals [17,18]. Thirdly, the higher frequency of severe NVP in patients with certain genetically determined conditions such as defects in taste sensation [19,20], glycoprotein hormone receptor defects [21–23], or latent disorders in fatty acid transport or mitochondrial oxidation [24,25], suggests that some portion of HG cases may be related to discrete, genetically transmitted disease states that are unmasked or exacerbated in pregnancy. Finally, in a previous survey administered by the Hyperemesis Education and Research Foundation, approximately 28% of cases reported their mother had severe nausea and vomiting or hyperemesis gravidarum while pregnant with them. Of the 721 sisters with a pregnancy history, 137 (19%) had hyperemesis gravidarum. Among the most severe cases, those requiring total parenteral nutrition or nasogastric feeding tube, the proportion of affected sisters was even higher, 49/198 (25%). Nine percent of cases reported having at least two affected relatives including sister(s), mother, grandmother, daughters, aunt(s), and cousin(s). There is a high prevalence of severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy/hyperemesis gravidarum among relatives of hyperemesis gravidarum cases in this study population [26]. Overall, these data suggest that genetic predisposition may play a role in the development of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. However, to our knowledge, a case-control study of familial aggregation of severe nausea and vomiting in pregnancy and hyperemesis gravidarum has never been done. The goal herein is to determine whether there is familial aggregation of severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and hyperemesis gravidarum in a case-control setting.

2. Methods

Recruitment

The University of Southern California–Los Angeles and the University of California, Los Angeles are currently conducting a study of the genetics and epidemiology of HG, and more than 650 participants have been recruited, primarily through advertising on the Hyperemesis Education and Research Foundation Web site at www.HelpHer.org. The inclusion criteria for cases are a diagnosis of HG and treatment with IV fluids and/or total parenteral nutrition/nasogastric feeding tube. Participants are asked to [1] submit their medical records, [2] provide a saliva sample, and [3] complete an online survey regarding family history, treatment, and outcomes. Each case is asked to recruit a friend with at least 2 pregnancies that went beyond 27 weeks to participate as a control. Controls are eligible if they experience normal (did not interfere with their daily routine) or no nausea/vomiting in their pregnancy, no weight loss due to nausea/vomiting and no medical attention in their pregnancy due to nausea. Eligibility questions for cases and controls are attached in Appendix A.

Survey

Participants were asked to report on the severity of nausea and vomiting of their family members according to the following definitions:

No nausea and vomiting-never felt nauseous and never vomited in this pregnancy.

Very little nausea and vomiting-felt nauseous and/or vomited for a total of 1–7 days during this pregnancy.

Typical nausea and vomiting-may have nausea and/or vomiting in this pregnancy but (all of the following must be true) 1) did not lose weight from nausea/vomiting and 2) was able to sustain normal daily routine most days with little change in productivity due to nausea/vomiting most of the time, and 3) no need to consult health professional for medical treatment due to nausea and vomiting.

More severe morning sickness-1) persistent nausea and vomiting that interfered with normal daily routine in this pregnancy but did NOT require IV hydration or TPN due to persistent nausea/vomiting. 2) May have consulted a medical professional to treat nausea and vomiting. 3) May have lost a few pounds or one kg.

Hyperemesis Gravidarum-persistent nausea and vomiting with weight loss that interfered significantly with daily routine, and led to need for 1) IV hydration or nutritional therapy (feeding by an iv (TPN) or tube (NG) through the nose), and/or 2) prescription medications to prevent weight loss and/or nausea/vomiting.

Other OR UNSURE - please describe in text box at end of section.

The survey used for this study can be found at: http://www.helpher.org/HER-Research/2007-Genetics/

Statistical Methods

Characteristics were summarized for both the case group and the control group, and compared between the two groups. For the characteristics race and current pregnancy, the Chi-square test was used to compare the difference between the two groups. For the characteristics age, pregnancy losses, number of living children, and voluntary (VT) termination, Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the two groups.

The familial aggregation of Hyperemesis Gravidarum was examined by modeling the probability of having one or more sisters with HG using the logistic regression method. The status whether a participant was a case or a control was assumed to affect the probability of having one or more affected sisters through a logit fashion, in this way the effect of being a case on having at least one affected sisters can be expressed in odds ratio (OR). If we use Y to denote the status whether a participant had one or more sisters with HG, i.e. Y=1 if a participant has one or more affected sisters, and Y=0 otherwise, then the probability that a participant had one or more affected sisters Pr(Y =1) was modeled as following,

| (1) |

Where, X denotes the status that whether a participant was a case or a control, i.e. X=1 if a participant was a case, and X=0 if a participant was a control; β0 is the regression intercept which was of little interest in this case; β1 is the regression coefficient for variable X, and the exponential of the estimated β1 is the estimated OR of being a case on having at least one affected sister, i.e. the odds of having one or more affected sisters for a case over the odds of having one or more affected sisters for a control. In this analysis, two definitions were used to define that a sister had HG. In the first definition, a sister was said to have HG if she had severity 4, more severe morning sickness and severity 5, Hyperemesis Gravidarum. In the second definition, a sister was said to have HG only if she had Hyperemesis Gravidarum (severity 5). Since the cases and controls were not perfectly matched in terms of race and white was the dominating race in both case group and control group, analyses were also conducted only on white women for both definitions of HG.

This study has been approved by Institutional Review Boards, USC IRB # HS-06-00056 and UCLA IRB # 09-08-122-01A.

3. Results

Sisters

Cases and controls are well matched for distribution of the number of pregnant and therefore informative sisters, as shown in Table 1. 207 cases and 110 controls had at least one sister with a pregnancy history and were included in the study of affected sisters. Age, race, and pregnancy characteristics of cases and controls with informative sisters are shown in Table 2. Cases were significantly more likely to report having a sister with more severe morning sickness or HG than controls (OR=5.6, p<.001), Table 3a.

Table 1.

Distribution of Number of Pregnant Sisters (N=317)

| Controls (N=110) | Cases (N=207) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of pregnant sisters (%) | 0.4854 | |||

| 1 | 74 (67.27%) | 146 (70.53%) | ||

| 2 | 23 (20.91%) | 45 (21.74%) | ||

| ≥3 | 13 (11.82%) | 16 (7.73%) | ||

Table 2.

Summaries for Several Characteristics

| Controls | Cases | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 37.92 (5.65) | 35.77 (6.13) | 0.0016 | |

| Pregnancies losses | 0.55 (0.88) | 0.62 (1.43) | 0.7597 | |

| No. of living children | 2.48 (1.00) | 1.89 (1.07) | <.0001 | |

| Pregnancy termination | 0.16 (0.44) | 0.24 (0.74) | 0.0664 | |

| Currently pregnant (%) | 9 (8.65%) | 36 (19.25%) | 0.0166 | |

| Race (%) | 0.0346 | |||

| White | 107 (97.27%) | 181 (87.44%) | ||

| African American | 0 (0.00%) | 10 (4.83%) | ||

| Asian | 0 (0.00%) | 3 (1.45%) | ||

| Hispanic | 2 (1.82%) | 4 (1.93%) | ||

| other | 1 (0.91%) | 9 (4.35%) | ||

Table 3.

| a. Distribution of Affected Sisters (All races, More Severe NVP and HG*) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Cases | P value | |

| Affected sisters | 9 (8.33%) | 68 (33.83%) | <.0001 |

| Unaffected sisters | 99 (91.67%) | 133 (66.17%) | |

| b. Distribution of Affected Sisters (All races, HG) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Cases | P value | |

| Affected sisters | 1 (0.93%) | 28 (13.93%) | <.0001 |

| Unaffected sisters | 107 (99.07%) | 173 (86.07%) | |

| c. Distribution of Missingness of Affected Sisters (All races) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Cases | P value | |

| Missing | 2 (1.82%) | 6 (2.90%) | 0.7186 |

| Non missing | 108 (98.18%) | 201 (97.10%) | |

| d. Distribution of Missingness of Affected Sisters (White only) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Cases | P value | |

| Missing | 2 (1.87%) | 4 (2.21%) | 1.000 |

| Non missing | 105 (98.13%) | 177 (97.79%) | |

More Severe Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy and Hyperemesis Gravidarum

Because the cases and controls were not perfectly matched with respect to race, and the majority of participants were white, the analysis was repeated with whites only and the odds ratios were very similar (OR=5.2, p<.001).

When excluding the less severe definition (more severe morning sickness) and looking at reports of sisters with HG only, cases were even more likely to report having a sister with HG than controls (OR=17.3, p=.005), Table 3b. Again, the analysis was repeated with whites only and the odds ratios were very similar (OR=17.9, p=.005). Very few cases and controls were missing data on the nausea and vomiting in pregnant sisters and the distribution of missingness was not significantly different between cases and controls as shown in Table 3c and 3d.

Mothers

469 cases and 216 controls were included in the analysis of mothers. Cases were significantly more likely to report an affected mother (p<.0001) as 33% of cases and only 8% of controls reported having a mother affected with HG or more severe morning sickness (Table 4a). Cases and controls were well-matched for distribution of missing data on affected and unaffected mothers (Table 4b).

Table 4.

| a. Distribution of Affected Mothers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Cases | P value | |

| Affected mothers | 15 (7.73%) | 143 (32.65%) | <.0001 |

| Unaffected mothers | 179 (92.27%) | 295 (67.35%) | |

| b. Distribution of Missingness of Affected Mothers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Cases | P value | |

| Missing | 22 (10.19%) | 31 (6.61%) | 0.1233 |

| Non missing | 194 (89.81%) | 438 (93.39%) | |

Maternal and Paternal Grandmothers

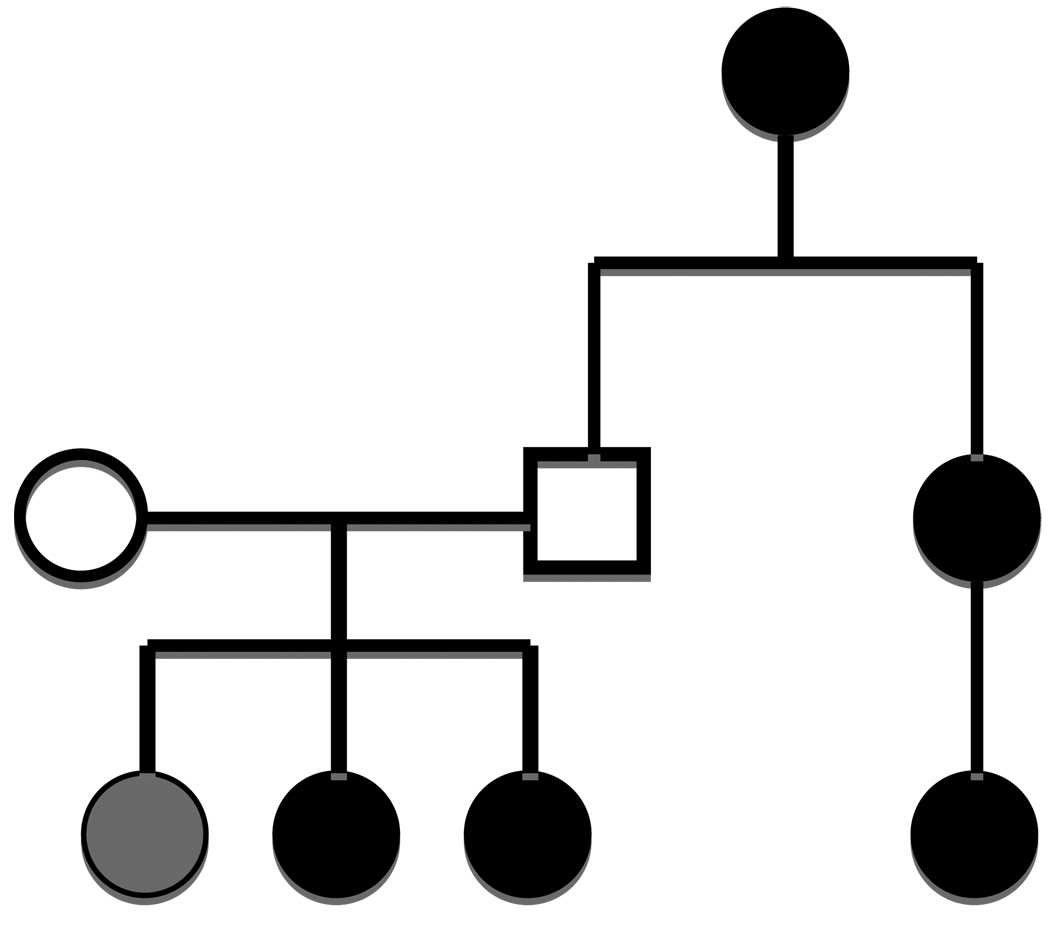

Cases and controls were NOT well matched with respect to missing data on second-degree relatives (maternal and paternal grandmothers) and therefore a comparison between cases and controls is not interpretable and is not included herein. However, 18% of cases reported an affected maternal grandmother and 23% of cases reported an affected paternal grandmother. Inheritance can pass through maternal and paternal lines and multiple generations as exhibited in the pedigree show in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

FAMILY A shows inheritance passes through maternal and paternal lines and multiple generations. Black circles=HG, Grey circle=More Severe Morning Sickness, No fill=not affected.

4. Comment

This study demonstrates a remarkably high risk of more severe morning sickness and HG among relatives of HG cases as approximately one-third of cases reported an affected mother and/or sister. The odds ratio is highest (OR=17) when comparing the proportion of affected sisters of cases to the proportion of affected sisters of controls using the most stringent definition of HG, rather than grouping HG and more severe morning sickness.

Although we realize that shared environmental risk factors can also contribute to the observed high prevalence of affected family members, to our knowledge no such factors have been identified. In addition, although sisters commonly have a similar in utero and childhood environment, it is unlikely that they share the same environment during their own pregnancy, when HG occurs. This study also suggests grandmothers, mothers, and daughters commonly share severe nausea of pregnancy and it is unlikely that this can be entirely explained by shared cross-generational environmental factors. Other reports of half-siblings reared in separate states and identical twins pregnant and diagnosed with HG while residing in different countries, although anecdotal, lend further support to a role for genetics [26].

The pedigree presented in this study, the fact that mothers and sisters are commonly affected, and the similar frequency of maternal and paternal grandmothers affected, suggest that, HG may be inherited in an autosomal dominant manner with incomplete penetrance, although other modes of inheritance in some families cannot be ruled out. Regardless of the mode of inheritance, this is the first case:control study of familial aggregation for hyperemesis gravidarum and in addition to previous studies showing higher concordance for nausea and vomiting in monozygotic vs. dizygotic twins [16] and a high prevalence of HG among family members of affected individuals [26] provides strong support for a genetic contribution to severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy.

HG often leads to extreme weight loss and may result in a state of nutrient deprivation, malnutrition, and starvation for both the mother and the developing fetus. Fetal outcome remains controversial. Some studies suggest infants exposed to HG in utero are significantly more likely to be born earlier, weigh less, be small for gestational age, and die between 24 and 30 weeks gestation than infants not so exposed [6]. Other studies show that these associated outcomes are only significant in cases with hyperemesis and low-pregnancy weight gain [7], and that, if treated early, severe nausea may be associated with a protective effect against major malformations [26]. While few long-term studies of HG offspring have been conducted, there is a body of literature on starvation in pregnancy in humans and animals, providing convincing evidence that nutritional deprivation in utero, can have lasting or lifelong significance [28]. These data, along with the evidence of a familial component to HG, suggest that healthcare providers should be vigilant in identifying and treating women with a family history of HG.

While our data implicate a strong maternal genetic component, other observations suggest that additional risk factors may influence severity of NVP. An increased incidence of HG has been reported with multiple gestations, gestational trophoblastic disease, fetal chromosomal abnormalities and central nervous system malformations, and for mothers of female offspring [8,29]. While smoking during pregnancy was recently reported to decrease the risk of hyperemesis, smoking by the partner was reported to increase the risk [4,8]. Other than second-hand smoke, to our knowledge, no environmental factors have been identified that increase risk. Non-genetic maternal factors such as advanced maternal age have been associated with decreased risk, and adolescent pregnancy with increased risk for HG [30,31]. Finally, evidence for a paternal and fetal contribution was controversial. While one study suggested that HG recurrence decreases with a change in partner, suggesting paternal genes expressed in the fetus may play a role, this conclusion was recently refuted by a separate study [32,33]. Additionally, a consanguinity study also found no increased risk of HG, suggesting recessive fetal genes may not be involved in HG risk [5].

A major strength of this study stems from the collaboration with the HER Foundation, which allowed collection of family history information on a large sample of women affected by HG. To date, most studies of hyperemesis gravidarum have been small case series or population studies relying on hospital databases with no information on family history. Thus this study is the first case-control report of its kind.

Admittedly, this study has some methodological concerns. One potential limitation arises from the use of an internet-based survey. While internet-based research is quickly becoming scientifically recognized as a reliable recruiting tool, the study population consists only of cases with internet-access, and thus may represent women of higher education and income. We feel, however, that the generalizability of our study results should be reasonably good since we have no reason to suspect that education level and income would affect the likelihood of having a family history of HG.

Another limitation is that family history of HG were based on self-reports, which can lead to misclassification of disease status and/or family history. However, we believe it would be highly unlikely for women to misclassify disease status of affected family members as they are given definitions to classify disease in family members and are required themselves to have been treated with iv therapy for severe nausea and vomiting.

Finally, the control group (friends of cases) was not perfectly matched for several characteristics. The controls were significantly older and had more living children than the cases which is likely due to the fact that while cases were eligible with only one pregnancy affected with HG, controls had to have completed at least one pregnancy and 2 trimesters of a second pregnancy without experiencing HG. The fact that controls on the whole were slightly older should not have any affect on the affected status of family members and sisters, in particular, because the number of pregnant and therefore informative sisters was similar for cases and controls. Cases were also more likely to be currently pregnant which is likely due to the fact that some cases searched the internet when they were diagnosed with HG and found the study information at that time. Again, we cannot think of a reason that this would bias the results. However, the cases were not well matched for race and this was of particular concern as genetic factors can be linked to race. We addressed this issue by repeating the analysis with the race that represented the majority for cases and controls (whites) and the results were very similar, suggesting that the differences in race do not affect the results of this study.

Because the incidence of hyperemesis gravidarum is most commonly reported to be 0.5% in the population and the sisters of cases have as much as an 18-fold increased familial risk for HG compared to controls, this study provides strong evidence for a genetic component to extreme nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. In summary, this study demonstrates that maternal genetic susceptibility plays a role in the development of severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy.

Future work should focus on reproducing these results in other populations and on the identification of genetic variants that may contribute to HG susceptibility. Identification of genetic factors will elucidate the biology of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy and allow novel therapeutics to be developed to treat the cause of the disease rather than the symptoms.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This case-control study of Hyperemesis Gravidarum, severe nausea/vomiting of pregnancy, shows strong familial aggregation of Hyperemesis Gravidarum, making it a disease amenable to genetic study.

References

- 1.Jiang HG, Elixhauser A, Nicholas J, Steiner C, Reyes C, Brierman AS. Care of women in U.S. hospitals, 2000. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Publication; 2002. HCUP fact book no. 3, No. 02-0044. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verberg MF, Gillott DJ, Al-Fardan N, Grudzinskas JG. Hyperemesis gravidarum, a literature review. Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11(5):527–539. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmi021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kallen B. Hyperemesis during pregnancy and delivery outcome: a registry study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1987;26(4):291–302. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(87)90127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang J, Cai WW. Severe vomiting during pregnancy: antenatal correlates and fetal outcomes. Epidemiology. 1991;2(6):454–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grjibovski AM, Vikanes A, Stoltenberg C, Magnus P. Consanguinity and the risk of hyperemesis gravidarum in Norway. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;12:1–6. doi: 10.1080/00016340701709273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailit JL. Hyperemesis gravidarum: epidemiologic findings from a large cohort. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:811–814. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodds L, Fell DB, Joseph KS, Allen VM, Butler B. Outcomes of pregnancies complicated by hyperemesis gravidarum. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(2):285–292. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000195060.22832.cd. Part 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fell DB, Dodds L, Joseph KS, Allen VM, Butler B. Risk factors for hyperemesis gravidarum requiring hospital admission during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(2):277–284. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000195059.82029.74. Part 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan PC, Jacob R, Quek KF, Omar SZ. The fetal sex ratio and metabolic, biochemical, haematological and clinical indicators of severity of hyperemesis gravidarum. BJOG. 2006;113(6):733–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuo K, Ushioda N, Nagamatsu M, Kimura T. Hyperemesis gravidarum in eastern Asian population. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2007;64(4):213–216. doi: 10.1159/000106493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gazmararian JA, Petersen R, Jamieson DJ, et al. Hospitalizations during pregnancy among managed care enrollees. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:94–100. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiossi G, Neri I, Cavazutti M, Basso G, Fucchinetti F. Hyperemesis gravidarum complicated by Wernicke’s encephalopathy: background, case report and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2006;61:255–268. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000206336.08794.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fairweather DVI. Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1968;102(1):135–175. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(68)90445-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Czaja JA. Food rejection by female rhesus monkeys during the menstrual cycleand early pregnancy. Physiol Behav. 1975;14(5):579–587. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(75)90185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoskins J. How to manage the pregnant bitch. DVM News. 2003 Retrieved from http://www.dvmnewsmagazine.com/dvm/article/articleDetail.jsp?id=70328&pageID=2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corey LA, Berg K, Solaas MH, Nance WE. The epidemiology of pregnancy complications and outcome in a Norwegian twin population. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80(6):989–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gadsby R, Barnie-Adshead AM, Jagger C. Pregnancy nausea related to women’sobstetric and personal histories. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1997;43:108–111. doi: 10.1159/000291833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vellacott ID, Cooke EJA, James CE. Nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1988;27:57–62. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(88)90088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sipiora ML, Murtaugh MA, Gregoire MD, Duffy VB. Bitter taste perception and severe vomiting in pregnancy. Physiol Behav. 2000;69:259–267. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00223-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartoshuk LM, Duffy VB, Reed D, Williams A. Supertasting, ear-aches and head injury: genetics and pathology alter our taste worlds. Appetite. 2002;38:45–51. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(95)00042-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodien P, Jordan N, Lefevre A, et al. Abnormal stimulation of the thyrotrophin receptor during gestation. Hum Reprod Update. 2004;10:95–105. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmh008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodien P, Bremont C, Raffin Sanson M, et al. Familial gestational hyperthyroidism caused by a mutant thyrotropin receptor hypersensitive to human chorionic gonadotropin. New Engl J Med. 1998;339(25):1823–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812173392505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akerman FM, Zhenmin L, Rao CV, Nakajim ST. A case of spontaneous ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome with a potential mutation in the hCG receptor gene. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:403–404. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)00628-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Innes AM, Seargeant LE, Balachandra K, et al. Hepatic carnitine palmitoyltransferase I deficiency presenting as maternal illness in pregnancy. Pediatr Res. 2000;47:43–45. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200001000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Outlaw WM, Ibdah JA. Impaired fatty acid oxidation as a cause for liver disease associated with hyperemesis gravidarum. Med Hypotheses. 2005;65:1150–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fejzo MS, Ingles SA, Wilson M, Wang W, MacGibbon K, Romero R, Goodwin TM. High prevalence of severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and hyperemesis gravidarum among relatives of affected individuals. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008 Nov;141(1):13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seto A, Einarson T, Koren G. Pregnancy outcome following first trimester exposure to antihistamines: meta-analysis. Am J Perinatol. 1997;14(3):119–124. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Painter RC, Roseboom TJ, Bleker OP. Prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine and disease in later life: an overview. Reprod Toxicol. 2005;20:345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eliakim R. Hyperemesis gravidarum: a current review. Am J Perinatol. 2000;17(4):207–218. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klebanoff MA, Koslowe PA, Kaslow R, Rhodes GG. Epidemiology of vomiting in early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;66:612–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Depue RH, Bernstein L, Ross RK, Judd HL, Henderson BE. Hyperemesis gravidarum in relation to estradiol levels, pregnancy outcome, and other maternal factors: a seroepidemiologic study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;156:1137–1141. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(87)90126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trogstad LI, Stoltenberg C, Magnus P, Skjaerven R, Irgens LM. Recurrence risk in hyperemesis gravidarum. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;112(12):1641–1645. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Einarson TR, Navioz Y, Maltepe C, Einarson A, Koren G. Existence and severity of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (NVP) with different partners. J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;27(4):360–362. doi: 10.1080/01443610701327362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]