Abstract

The calcium-regulated transcription factor NFAT is emerging as a key regulator of neuronal development and plasticity but precise cellular consequences of NFAT function remain poorly understood. Here, we report that the single Drosophila NFAT homolog is widely expressed in the nervous system including motor neurons and unexpectedly controls neural excitability. Likely due to this effect on excitability, NFAT regulates overall larval locomotion and both chronic and acute forms of activity-dependent plasticity at the larval glutamatergic neuro-muscular synapse. Specifically, NFAT-dependent synaptic phenotypes include changes in the number of pre-synaptic boutons, stable modifications in synaptic microtubule architecture and pre-synaptic transmitter release, while no evidence is found for synaptic retraction or alterations in the level of the synaptic cell adhesion molecule FasII. We propose that NFAT regulates pre-synaptic development and constraints long-term plasticity by dampening neuronal excitability.

Keywords: Drosophila, NFAT, Plasticity, Synapse, Neuron, Transcription

Introduction

The Drosophila third instar larval neuro-muscular junction has served as a robust model to investigate synaptic function, mechanisms of synaptic development and synaptic plasticity including homeostatic regulation of growth and transmitter release (Brunner and O’Kane, 1997; Ruiz-Canada and Budnik, 2006; Sanyal and Ramaswami, 2006). In particular, the role of key plasticity-related transcription factors such as CREB and Fos have been studied in detail and have contributed to a widely held model of activity and protein synthesis-dependent long-term plasticity, that crucially involve such transcription factors (Davis et al., 1996; Freeman et al.; Hoeffer et al., 2003; Sanyal et al., 2002). Since these transcription factors appear to perform conserved functions in all invertebrate and vertebrate models tested, studies in Drosophila have the power to illuminate the function of other hitherto unstudied transcription factors in neural development and plasticity. Recently, in a screen devised to identify genes that modify a Fos-dependent synaptic phenotype, we isolated alleles of the fly homolog of the transcription factor NFAT (Franciscovich et al., 2008). Since numerous studies have documented functional interactions between Fos (and the hetero-dimeric transcription factor AP-1) and NFAT in non-neuronal cells (Rao et al., 1997), we investigated neuronal functions of NFAT at the Drosophila NMJ.

In recent years, the transcription factor NFAT (Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cells) has been steadily emerging as an important regulator of neural development and plasticity (Graef et al., 1999; Graef et al., 2003; Kao et al., 2009; Schwartz et al., 2009). For instance, mice mutant for multiple NFAT genes have abnormally developed dorsal root ganglion neurons and in vitro experiments suggest aberrant responses to growth factor stimulation (Graef et al., 2003). Similarly, a GSK-3-Calcineurin-NFAT signaling module is known to operate in hippocampal neurons and actively participates in the growth and plasticity of tectal neuron dendrites in the tadpole (Graef et al., 1999; Schwartz et al., 2009). In these model systems (as in T-cells), the Calcium regulated phosphatase Calcineurin controls NFAT nuclear entry, and thereby NFAT-dependent transcription, by dephosphorylating conserved amino acid residues. While these studies have highlighted conserved and important neural roles for Calcineurin and NFAT, precise functional consequences of NFAT on pre-synaptic growth and transmitter release, potential cellular mechanisms downstream of NFAT, and its impact on behavioral outputs of the nervous system have not been investigated (Nguyen and Di Giovanni, 2008).

In the present report, we address this deficiency by presenting an extensive analysis of the single Drosophila NFAT homolog. We show that neuronal NFAT inversely regulates the number of pre-synaptic boutons and pre-synaptic transmitter release at this synapse. Although we find no evidence for altered synaptic retraction, mislocalization of both pre-(Shi/Dynamin) and post-synaptic (Dlg/PSD-95) proteins, or changes in levels of the neural cell adhesion molecule FasII, we do detect strong variations in the number of MAP1B (Futsch) labeled synaptic microtubule loops in NFAT manipulated synapses. Functionally, our results suggest that NFAT attenuates the intrinsic excitability of motor neuron in vivo. Consistently, this altered excitability leads to measurable changes in larval locomotor behavior. Finally, we demonstrate that NFAT also inhibits both chronic and acutely induced activity-dependent pre-synaptic plasticity in these motor neurons.

The potency of neural activity to regulate neural development and plasticity is firmly established. Thus, across model systems, changes in activity or excitability profoundly impact both short- and long-term plasticity. Indeed several transcription factors involved in plasticity and behavioral adaptation such as Fos, CREB and Zif-268 have been shown to be responsive to changes in neural activity (Bartsch et al., 1998; Cole et al., 1989; Flavell and Greenberg, 2008; Hoeffer et al., 2003; Hope et al., 1992; Kaang et al., 1993; Sanyal and Ramaswami, 2006; Wayman et al.; Wong and Ghosh, 2002). However, whether these or other plasticity-related transcription factors might themselves alter excitability in neurons is relatively poorly explored. Our results, in addition to establishing NFAT as a regulator of neural development and plasticity, also reveal an unexpected function of NFAT in the maintenance of normal neuronal excitability. While the precise molecular mechanism by which NFAT might influence neural activity remains a topic of future investigation, our current findings suggest a model in which NFAT restricts activity-dependent plasticity by directly modulating neuronal excitability.

Results

A single Drosophila NFAT homolog is expressed in the nervous system

Drosophila has only one NFAT homolog (CG 11172) with two splice isoforms (Keyser et al., 2007) that is 53% similar to mammalian NFATc2 and 64% similar to mammalian NFAT5. Key diagnostic features of NFAT are conserved including the Rel Homology Domain (RHD), part of the Calcineurin binding domain and a subset of amino acid residues that mediate direct interactions with the AP-1 transcription factor (Chen et al., 1998; Clipstone and Crabtree, 1992; Kao et al., 2009; Rao et al., 1997) (Figure 1A). We identified NFAT in a screen for genetic interactors of AP-1, and found that pan-neuronal NFAT over-expression from two EP lines (19579 and 1508) causes observable phenotypes in synaptic structure at the larval muscle 6/7 neuro-muscular synapse as reported previously in a separate screen (Franciscovich et al., 2008; Kraut et al., 2001). EP elements contain multiple GAL4 responsive UAS sites at their 3′ ends (Rorth, 1996) and when inserted upstream of gene coding regions, enable directed expression of the downstream gene in a spatio-temporal domain of interest. We sequence verified the insertion site and orientation of the two EP lines, to confirm that 19579 is in a position to drive expression of NFAT isoform A (NFAT-A) while 1508 can drive expression of NFAT isoform B (NFAT-B) (Figure 1A; note that the two isoforms differ only in their first exon). To carry out loss-of-function analysis of NFAT, we also obtained a previously described deletion allele (NFATΔAB) from Daniel Hultmark (Umeå university, Sweden) (Keyser et al., 2007). This deletion removes common exons 2 and 3 that are shared between NFAT-A and NFAT-B and should, therefore, eliminate expression of the full length NFAT-A and B isoforms (Figure 1A). We did not detect a truncated protein in our western analysis of this deletion allele, suggesting that this allele is most likely null for NFAT expression (see below). In our own attempts at generating excision alleles, we recovered two independent lines that remove either the first exon of NFAT-A (NFATΔA) or NFAT-B (NFATΔB). These lines were isolated by excising either EP19579 or EP1508 respectively, and were sequenced to confirm the extent of these deletions.

Figure 1. Drosophila NFAT is expressed in the nervous system.

A) Schematic of the NFAT gene showing exon-intron boundaries and two NFAT transcripts, NFAT-A and NFAT-B (specific riboprobes to these transcripts are designated RP-A and RP-B). Also shown are insertion sites for the two EP elements (19579 and 1508) that predictably drive expression of the NFAT-A or NFAT-B isoforms respectively, the site of insertion of the GFP exon trap element, and the region targeted by the NFAT-RNAi construct. The conserved Rel-Homology Domain (RHD) spans exons 5 and 6 and the NFAT deletion ΔAB used in this study eliminates shared exons 2 and 3. B) Western blot of brain protein extracts probed with antibodies raised against the C-terminal of NFAT. A band of the predicted molecular weight (~150 KD) is recognized in wild type brains, is absent in the deletion mutant heterozygous over a non-complementing deficiency and is present in higher level when either NFAT-A or NFAT-B is overexpressed pan-neuronally using the elavC155-GAL4 driver line. C) RNA in situ experiments on larval brains with riboprobes directed against either NFAT-A or NFAT-B. Isoform specific mRNA is detected in larval brains that are absent in the deletion mutant and increased in specific over-expression conditions. Sense probe is used as a control. D) Larval ventral nerve cords from NFAT-A::GFP animals double stained for Elav (top row) and expressing nls-dsRed in motor neurons using a C380(Futsch)-GAL4 (bottom row; arrow marks motor neuron nuclei) to show that NFAT-A is expressed in larval motor neurons. E) Pan-neuronal expression of NFAT-RNAi knocks down NFAT-A::GFP expression in larval brains (bottom) as compared to controls (top). Elav counter-staining is used to label all post-mitotic neurons (top and bottom left panels). GFP staining is used to detect endogenous NFAT::GFP fusion protein (top and bottom right panels). Inset shows close-up of dorsal medial motor neurons from one segment, while arrows mark cluster of neurons in the brain that express NFAT-A::GFP that lose expression following RNAi mediated knock-down of NFAT.

In order to define the endogenous expression pattern of NFAT we raised antibodies in rabbits against a bacterially expressed recombinant protein comprising Glutathione S-transferase and the C-terminal portion of Drosophila NFAT (amino acids 989–1419; materials and methods). This affinity-purified antibody recognizes a band of the predicted molecular weight (approximately 150 KD) on western blots from adult and larval brain extracts (Figure 1B). Expectedly, over-expression of this protein from the two EP lines (EP19579 = NFAT-A and EP1508 = NFAT-B) using the GAL4-UAS system (Brand and Perrimon, 1993) (elavC155-GAL4) results in a stronger band on this western, while a genomic deletion for NFAT (NFATΔAB) eliminates expression of this protein. Consistent with NFAT protein expression, presence of NFAT mRNA was also detected in larval brains through RT-PCR (supplementary Figure 1A) and RNA in situ experiments (Figure 1C). When probed with isoform-specific probes that are complementary to the first exon of either NFAT-A or B, isoform-specific expression was detected in larval brains. This is most evident when either NFAT-A or B is expressed in the larval brain using a pan-neuronal elavC155-GAL4 driver. Thus, these experiments also directly verified that EP19579 and 1508 can be used to over-express either NFAT-A or NFAT-B respectively in the brain when combined with an elavC155-GAL4. Similarly, we found that the genomic deletion (NFATΔAB) does not have detectable NFAT mRNA (Figure 1C and supplementary Figure 1A).

Since our antibodies did not prove to be useful for immuno-histochemistry, we could not detect endogenous NFAT protein in tissues with this reagent. However, we identified a pre-existing GFP “splice trap” strain in which a GFP exon flanked by splice acceptor and donor sites is integrated into the first intron of the NFAT-A gene (Figure 1A and supplementary Figure 1) such that GFP is spliced in frame with the endogenous NFAT-A transcript (Buszczak et al., 2007). Reverse transcriptase PCR and sequencing of the NFAT-A transcript from this homozygous viable line confirmed that the coding sequence for GFP is indeed integrated between exons 1 and 2 in the NFAT-A transcript (supplementary Figure 1 A and B). Additionally, we also detected the presence of a fusion protein of the expected size when we probed a western blot of protein extract from the NFAT::GFP strain with anti-NFAT or anti-GFP antibodies (supplementary Figure 1C and 1D). Staining larval and adult brains in this strain for GFP showed widespread expression of NFAT in the nervous system (in addition to some non-neuronal cells) including larval glutamatergic motor neurons that are marked by the C380-GAL4 line (Figure 1D; for adult brain staining see supplementary Figure 2) (Sanyal, 2009). In neurons, NFAT staining appears restricted to nuclei suggesting a predominantly different steady-state cellular localization than its vertebrate counterpart which is known to shuttle between the cytoplasm and nucleus based on its phosphorylation state (Graef et al., 1999; Loh et al., 1996; Schwartz et al., 2009). That this staining indeed represents functional endogenous NFAT is further confirmed through RNAi mediated knock down of NFAT (and hence of GFP fluorescence) in a tissue specific manner, and by the observation that NFAT::GFP heterozygous over a genomic deficiency that removes NFAT (Df(1)ED7217: 12A9-12B2) produces completely viable adults whereas the NFATΔAB allele does not (suggesting that NFAT::GFP has normal NFAT activity). Additionally, NMJ size (bouton numbers) and various parameters of pre-synaptic transmitter release in NFAT::GFP homozygous animals are indistinguishable from wild type (supplementary Figure 3). Expression of NFAT-RNAi in neurons or muscle strongly attenuates NFAT::GFP staining in that particular tissue (Figure 1E and supplementary Figure 4). Specifically, as shown in the inset images in Figure 1E, NFAT::GFP expression in the dorsal medial cluster of larval motor neuron (top row shows larval brains from the NFAT::GFP line stained for Elav and GFP) is abolished through expression of NFAT RNAi in these neurons (bottom row shows the NFAT::GFP line in which NFAT RNAi is expressed pan-neuronally; while Elav staining persists, GFP staining is almost completely eliminated). In sum, these results demonstrate that a) both Drosophila NFAT mRNA and protein are normally expressed in the nervous system including motor neurons and, b) our experimental reagents can be used effectively to either overexpress or knock down NFAT in vivo.

NFAT regulates pre-synaptic growth

Our results suggest that neuronal NFAT regulates the number of pre-synaptic boutons. NFATΔAB mutants (either homozygous or heterozygous with the non-complementing genomic deficiency) have expanded synapses as compared to controls (measured by counting synaptotagmin labeled pre-synaptic puncta or boutons at the stereotypic muscle 6/7 synapse) and a precise excision line, while average muscle surface area remains unaffected (supplementary Figure 5). As compared to this larger deletion allele, deletion of either NFAT-A (NFATΔA) or NFAT-B (NFATΔB) had minimal effects on NMJ size (Keyser et al., 2007) (Figure 2A and 2B; Mean bouton numbers: NFATΔAB/Df(1)ED7127 = 206+/−9; Df(1)ED7127/w1118 = 151+/−5; p<0.001). Similarly, pan-neuronal RNAi mediated knock down of NFAT achieved through the expression of NFAT-targeted dsRNA from the elavC155-GAL4 driver also results in NMJs larger than control animals (Mean bouton numbers: elavC155 control = 133+/−6; NFAT-RNAi = 162+/−6; p<0.001). Contrarily, expression of either NFAT-A or NFAT-B in neurons using the same pan-neuronal GAL4 driver line (elavC155-GAL4) results in synapses that are significantly smaller than appropriate genetic controls (Mean bouton numbers: w1118 = 137+/−3; NFAT-A = 67+/−3; NFAT-B = 106+/−4; p<0.001) (Figure 2A and 2B). Rescue of synaptic phenotypes observed in the NFATΔAB deletion allele with the wild type NFAT transgene has been hampered by the non-availability of a full-length NFAT cDNA (we found the cDNA available from DGRC to be a truncated transcript, suggesting perhaps more complex transcriptional regulation at the NFAT locus). In an alternate strategy, we asked whether synaptic phenotypes resulting from over-expression of NFAT were due to the transcriptional activity of the NFAT protein. To this end, we generated an NFAT dominant-negative transgene that solely expresses the RHD domain (predicted to be involved in transcriptional regulation) of NFAT without the transcription activating region (materials and methods), with the idea that this protein could interfere with endogenous or over-expressed NFAT function. When co-expressed with normal NFAT from either of the two EP lines, smaller NMJs due to NFAT over-expression alone are rescued to wild type sizes by this NFAT-RHD transgene. This observation suggests that the RHD domain in Drosophila NFAT is functionally active and the transcriptional activity of NFAT is required for NFAT-mediated synaptic growth phenotypes (Heckscher et al., 2007). Although NFAT is normally expressed in larval muscle tissue as well (Supplementary Figure 4), post-synaptic muscle expression of NFAT (Sanyal et al., 2005) using a mef2-GAL4 driver line had no observable effect on NMJ size, suggesting a pre-synaptic locus for these phenotypes. Together, these results confirm negative regulation of pre-synaptic growth by NFAT. Interestingly, expression of either NFAT-A or NFAT-B partially suppresses the effect of AP-1 on synapse growth (Figure 2B). However, since co-expression of NFAT and AP-1 results in a synapse that has an intermediate number of boutons, a clear epistatic relationship between NFAT and AP-1 seems unlikely. As such it is difficult to define a precise hierarchical relationship between these two transcription factors in the regulation of Drosophila synaptic development, though they seem to regulate NMJ growth antagonistically. It is to be noted that this situation is somewhat reminiscent of that in vertebrate T-cells (Macian et al., 2002).

Figure 2. Neuronal NFAT negatively regulates pre-synaptic bouton number.

A) Representative images from synaptotagmin stained muscle 6/7 neuro-muscular synapses at the larval body wall in abdominal segment A2. The number of independent synaptotagmin stained puncta is used as a measure of NMJ size. Loss of NFAT in a deletion mutant or neuronally targeted RNAi-mediated knock-down of NFAT results in more numerous synaptic boutons, while neuronal expression of either NFAT-A or NFAT-B produces a smaller NMJ. The pan-neuronal elavC155-GAL4 driver was used for pan-neuronal expression. Scale bar = 25μm. B) Quantification of bouton numbers across genotypes to show that pre-synaptic perturbation of NFAT influences bouton number while post-synaptic manipulations (using a muscle specific Mef2-GAL4 driver line) are ineffective. Loss of NFAT in deletion mutants (NFATΔAB) and following RNAi-mediated knock-down in neurons results in NMJs that are significantly larger than genetically matched controls. Conversely, expression of wild type NFAT pan-neuronally results in fewer pre-synaptic boutons. Co-expression of wild type NFAT with the RHD domain of Drosophila NFAT results in partial rescue of the NFAT-mediated small NMJ phenotype. Although NFAT is expressed in larval muscles, over-expression of NFAT in muscles using the mesoderm-specific Mef2-GAL4 driver does not alter pre-synaptic growth. NFAT also antagonizes the growth promoting effect of the transcription factor AP-1 (a dimer of fos and jun) on these synapses. As a result animals co-expressing NFAT and AP-1 have NMJs that are intermediate and not significantly different from wild type animals. Co-expression of NFAT with the bZip domain of Fos (FBZ; this leads to AP-1 inhibition) leads to small NMJs that are similar in size to expression of either FBZ or NFAT alone. This suggests that NFAT and AP-1 antagonize one another in pre-synaptic growth control. Numbers on the histograms, in this graph and in all others, are the number of NMJs analyzed for that genotype.

NMJ size, estimated by counting the number of synaptic boutons in this case, can be altered either through changes in rates of synapse growth or synapse retraction (Eaton et al., 2002; Keller-Peck et al., 2001). Synaptic retraction has previously been reported at this synapse and is measured by double-staining the synapse for a pre-and post-synaptic marker. If synaptic retraction has taken place, then post-synaptic densities are observed without corresponding pre-synaptic boutons (synaptic “footprints”; (Collins and DiAntonio, 2007)). Since these synapses are generally considered to be stable by the end of the larval period, and post-synaptic densities are usually formed opposite existing pre-synaptic contacts, the presence of isolated post-synaptic densities is considered a mark of synaptic retraction. To measure retraction, we co-stained NFAT manipulated synapses with antibodies against the pre-synaptic protein Shibire (the Drosophila Dynamin homolog) and the membrane associated synaptic scaffold protein Dlg (Drosophila PSD-95) (Estes et al., 1996; Lahey et al., 1994). In addition to normal Dyn and Dlg sub-synaptic localization (Figure 3A high magnification images for control and NFAT-A overexpression synapses), we found no evidence for altered synapse retraction when NFAT was increased or decreased in neurons (Eaton et al., 2002). Figure 3A and 3C show that no “footprints” are found at the muscle 4 NMJ in any genotype tested, while the effect of NFAT perturbation on bouton number is consistently observed at this synapse, using a different pre-synaptic marker (Dynamin). These results suggest that NFAT might alter the rate or manner of synapse growth. To determine potential mechanisms for altered synaptic growth we first focused on a Drosophila neural cell adhesion molecule, FasII, a protein that has been implicated in synapse growth regulation in several previous studies (Koh et al., 2002; Sanyal et al., 2002; Schuster et al., 1996b). However, FasII protein levels in terminal boutons, normalized to anti-HRP staining intensity in the same boutons, remain invariant under conditions of NFAT over-expression, suggesting alternate means of growth regulation (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. NFAT-dependent changes in NMJ growth correlate with altered Futsch (MAP1B) staining.

A) Representative muscle 4 synapse images double stained for Dynamin (anti-Shibire, pre-synaptic marker) and PSD-95 (anti-Dlg, post-synaptic marker) show no postsynaptic structures without corresponding presynaptic terminals, which would be evidence of synapse retraction. Higher magnification images are shown for control and NFAT-A synapses to show normal localization of these two synaptic proteins suggesting grossly normal sub-synaptic architecture (scale bar = 1 μm). However, note that the architecture of terminal synaptic boutons is significantly different in animals expressing NFAT with a cluster of terminal synaptic boutons. B) Double stained (anti-HRP and anti-Futsch) synapses in control (top) and NFAT-A overexpressing synapses (bottom; C155 = elavC155-GAL4) showing the presence of more than twice as many Futsch-positive microtubule loops per synapse following neuronal NFAT expression. Arrows mark Futsch loops and inset shows these in close-up. Scale bar = 10μm. C) Bouton numbers (counted in this case using anti-Shibire staining) were affected as described before through NFAT perturbations. D) Synaptic FasII (measured as a ratio of FasII fluorescence staining intensity to HRP staining intensity for each synapse analyzed) levels were unaltered following neuronal expression of NFAT. E) Quantification of the number of Futsch positive loops per NMJ. Neuronal expression of either NFAT-A or NFAT-B increases while loss of NFAT decreases the number of Futsch labeled loops significantly, as compared to controls. F) Synapse length (the expanse of the pre-synaptic arbor on muscle 6) is reduced in NFAT overexpressing NMJs. Thus, expression of either NFAT-A or NFAT-B in motor neurons using the motor-neuron specific GAL4, D42, results in NMJs with reduced length as compared to the D42 line alone. This phenotype is rescued through reduction in the gene dosage of Futsch using the hypomorphic allele futschN94.

Next, we noticed that NFAT over-expression resulted in clusters of terminal synaptic boutons and an overall reduction in the expanse of the pre-synaptic arbor (note clusters of terminal boutons following neuronal NFAT expression in enlarged panels of Figure 3A). To test the hypothesis that these synapses represent abnormal growth where multiple terminal boutons surround an older bouton, we stained for the microtubule binding protein, Futsch (Roos et al., 2000) (the Drosophila MAP1B homolog). In stable terminal boutons, Futsch is known to decorate closed loops of synaptic microtubules (Roos et al., 2000; Ruiz-Canada et al., 2004). If multiple terminal synaptic boutons are found in NFAT over-expressing synapses, then we predicted that these boutons should contain closed Futsch decorated microtubule loops. Consistent with our hypothesis, the number of Futsch positive microtubule loops is increased dramatically in NFAT over-expressing animals, while NFAT deletion animals had significantly fewer loops as compared to controls (Mean number of Futsch labeled loops per synapse: w1118 = 14+/−1; NFAT-A = 21+/−2; NFAT-B = 27+/−1; NFATΔAB/Df(1)ED7127 = 11+/−1; p<0.001) (Figure 3B and 3E). When we measured the length of these synapses (mean longitudinal distance covered by pre-synaptic varicosities on muscle 6), we observed a significant reduction in NFAT over-expression synapses. To test whether this reduced synaptic length might correlate with Futsch, we reduced the gene dosage of Futsch using the hypomorphic FutschN94 allele in the background of NFAT expression (Roos et al., 2000). Results shown in Figure 3F indicate that reducing Futsch restores normal synaptic length when NFAT is expressed in motor neurons with the D42-GAL4 (Sanyal, 2009). Thus, using multiple markers of synapse growth and a motor neuron enriched GAL4 line, these observations together confirm that NFAT negatively regulates synapse growth and also point to an important role for the microtubule binding protein Futsch in NFAT mediated regulation of synapse growth.

NFAT regulates transmitter release at the NMJ

In addition to regulating NMJ growth, NFAT also negatively controls transmitter release from the pre-synaptic terminal. Thus, neuronal expression of either NFAT-A or NFAT-B reduces (Mean EJC amplitude: p<0.001), while loss of NFAT increases transmitter release (Mean evoked junction current or EJC amplitude: w1118 = 83+/−3 nA; NFAT-A = 67+/−3 nA; NFAT-B = 34+/−5 nA; Df(1)ED7127/w1118 = 79+/−4; NFATΔAB/Df(1)ED7127 = 94+/−6; p<0.001) as determined by measurements of evoked excitatory junctional current (EJC) amplitudes under two-electrode voltage clamped conditions (Figure 4A and 4C). These changes are pre-synaptic in origin since average amplitudes of spontaneous release (mini EJCs) are comparable across genotypes and not significantly different (Figure 4D). Therefore, the quantal content of transmitter release, i.e. the number of synaptic vesicles released per action potential, (measured by dividing the mean EJC amplitude by the mean mEJC amplitude for each recording) is negatively regulated by NFAT (Figure 4E). For reasons currently unclear a stronger reduction in quantal content was observed with NFAT-B than with NFAT-A which is in apparent opposition to the effect seen on synapse growth (Figure 2). It is possible that homeostatic mechanisms act differently based on expression levels of NFAT-A and NFAT-B to result in the final state of the synapse vis-à-vis growth and transmitter release. We also observed some variations in mEJC frequency but these did not correlate in any meaningful manner with levels of NFAT expression and are likely unlinked to NFAT (Figure 4F).

Figure 4. NFAT negatively regulates pre-synaptic transmitter release.

A) Representative traces of Evoked Junction Currents (EJCs) and miniature EJC (mEJCs) measured using two-electrode voltage clamp from muscle 6 in larval abdominal segment A2. Neuronal expression of NFAT-A or NFAT-B from the elavC155-GAL4 driver results in smaller EJCs, while loss of NFAT in the NFATΔAB allele results in significantly larger EJC amplitudes. Vertical scale bar for EJC = 20nA, and mEJC = 5nA; horizontal scale bar = 200 ms. B) EJC measurements at three different calcium concentrations shows that calcium dependence of transmitter release is altered in NFAT manipulated animals at higher concentrations of calcium, with loss of NFAT increasing and overexpression of NFAT reducing transmitter release. C) Quantification of mean EJC amplitude in different genotypes shows that pan-neuronal expression of either NFAT-A or NFAT-B results in smaller mean EJC amplitudes while loss of NFAT in NFATΔAB produces a larger EJC. D) mEJC amplitudes are comparable across genotypes. Average mEJC amplitudes were calculated from 2 minutes of continuous recordings in each animal. E) Increased pan-neuronal NFAT expression decreases the quantal content of transmitter release, while loss of NFAT increases it. Quantal content is measured by dividing the mean EJC amplitudes by the mean mEJC amplitude for each recording. F) The frequency of spontaneous release, mEJC frequency, is comparable across genotypes with no significant differences. These recordings show that NFAT influences the quantal content of transmitter release without affecting quantal size or mini frequency. G) Quantification of total Brp labeled spots per NMJ in different genotypes measured by counting the number of individual puncta labeled by the monoclonal antibody nc82. The total number of Brp positive active zones are not altered either through expression of NFAT-A or NFAT-B or in an NFAT loss of function background.

Changes in the quantal content of release might arise due to alterations in the number of release sites or active zones (Kim et al., 2009; Marrus and DiAntonio, 2004). However, when we counted the number of active zones at the muscle 6/7 synapse using staining for an active zone localized protein Bruchpilot (Wagh et al., 2006) and a semi-automated method that uses a software commonly used to detect protein spots in 2D-electrophoresis (supplementary Figure 6; see materials and methods), we found these numbers to be mostly invariant across all genotypes tested (Figure 4G) (Kim et al., 2009). We concluded that NFAT does not alter transmitter release by affecting the number of active zones, and therefore is likely to influence the probability of synaptic vesicle release. Consistent with this idea, the calcium responsiveness of transmitter release differs significantly between control and NFAT manipulated animals. For instance, recordings of EJCs at 1.1 mM external calcium shows that while neuronal expression of NFAT-A or NFAT-B limits EJC amplitude (as compared to controls), loss of NFAT results in a greater increase in EJC amplitude with elevated external calcium (Figure 4B). However, a precise determination of changes in release probability will require further measurements of transmitter release derived from paired-pulse facilitation experiments and quantal analysis. Together with demonstrations of synapse growth regulation, these data show that NFAT belongs to a select group of transcription factors that control both pre-NMJ size and strength at this synapse similar, for example, to AP-1, but distinct from CREB and Adf-1 (Davis et al., 1996; DeZazzo et al., 2000; Sanyal et al., 2002).

NFAT suppresses neuronal excitability in Drosophila larval motor neurons

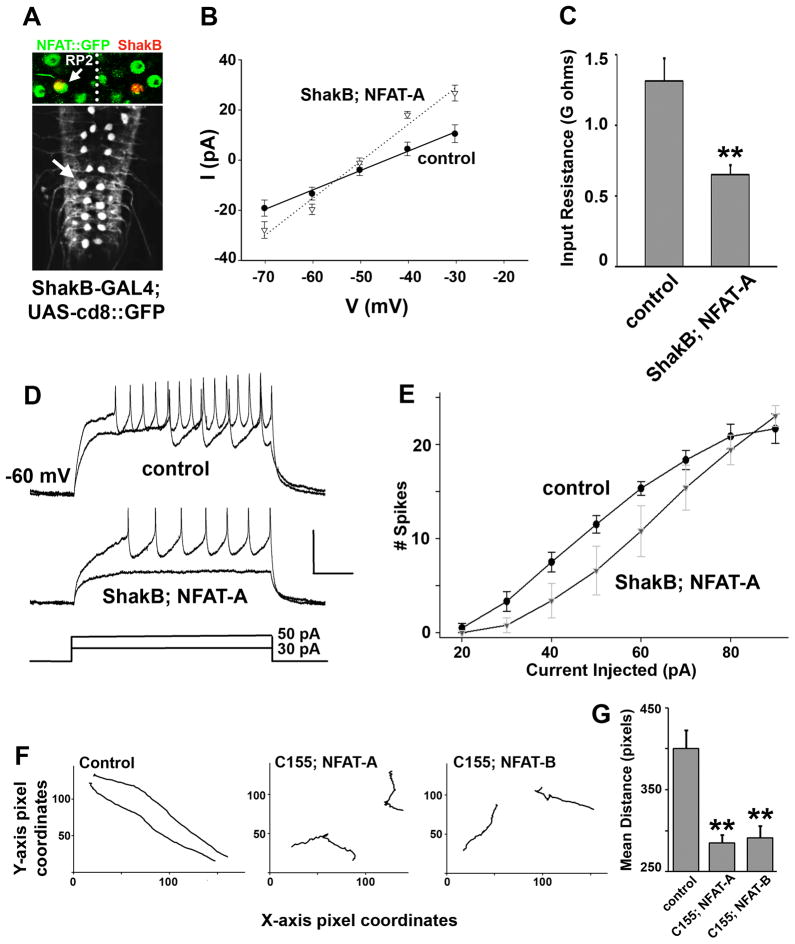

Since NFAT controls pre-synaptic growth and transmitter release, but apparently not through modulation of either active zone number or the NCAM homolog FasII, we considered the possibility that NFAT regulates neuronal excitability. Abnormal neuronal excitability can alter synaptic morphology through cellular processes including microtubule rearrangements (Budnik et al., 1990; Davis et al., 1996; Freeman et al.; Mosca et al., 2005) and can directly affect the probability of neurotransmitter release (Sandstrom, 2004). Moreover, initial examination suggested altered overall motor activity following neuronal expression of NFAT (see below). To directly test the outcome of increased neuronal NFAT on excitability, we performed patch-clamp measurements on the well characterized and easily identified dorso-medial RP2motor neuron in larvae. Figure 5A shows the dorsal surface of a larval ventral nerve cord (VNC) expressing GFP in RP2 neurons from a ShakB-GAL4 line (materials and methods) (Takizawa et al., 2007). RP2 neurons also express NFAT, since NFAT::GFP staining overlaps with ShakB-GAL4 driven expression of nuclear localized β-galactosidase. Overexpression of NFAT-A dramatically reduces the excitability of RP2, in that the input resistance (Rin) measured in voltage clamp is reduced to half of the wildtype (Mean Rin: control = 1.31+/− 0.16; NFAT-A = 0.65 +/− 0.39; p < 0.01; Figure 5B and C). As a consequence of this drastic increase in the leakiness of the cell, NFAT neurons depolarize much less, and produce fewer action potentials than controls for the same magnitude of current injected (Figure 5D and E), and therefore, require a greater degree of synaptic current to fire action potentials. As a result, we expect that neurons with more NFAT should have considerably reduced input-output properties in vivo.

Figure 5. NFAT regulates neuronal excitability.

A) The ShakB-GAL4 line is used to visualize RP2 motor neurons in the larval ventral nerve chord, and to express NFAT-A in these neurons. Upper image shows co-localization of NFAT::GFP with ShakB-GAL4 driven nuclear β-galactosidase, confirming that NFAT is endogenously expressed in RP2 motor neurons. B) Current-voltage relations for wild-type RP2 neurons (filled circles, solid line) and those expressing NFAT-A (open triangles, dotted line). Each data point is the mean of five experiments, and the regression lines are fit through the means. C) Quantification of input resistance. Expression of NFAT-A significantly reduced the input resistance of RP2, measured as the slope of the I–V relation. D) Representative traces showing the effect of current injection (bottom) into wild-type (top) and NFAT-A-expressing RP2 (middle). As expected from its reduced input resistance, the NFAT-A neuron depolarizes less and fires fewer spikes than the wildtype. E) Quantification of spiking responses to current injection. At almost all current levels, NFAT-A-expressing RP2s fired fewer action potentials. F) Crawling profiles of two animals for each genotype. X and Y axes represent pixel dimensions such that all tracks are to the same scale. Expression of either NFAT-A or NFAT-B pan-neuronally results in significantly slower and uneven crawling patterns. G) Mean distance moved by ten larvae of each genotype in 1 minute. NFAT-A or NFAT-B expression in all neurons results in smaller distances traveled as compared to wild type control animals.

Translated to the whole nervous system, the above reduction in excitability is expected to produce observable behavioral consequences. To measure behavioral output, we assayed crawling patterns in freely moving wandering third instar larvae following chronic manipulations in neuronal NFAT. Larvae were imaged individually on agar plates containing no sucrose for a total period of 1 minute. Larval crawling patterns were tracked and measured using ImageJ (see materials and methods) and distance traveled compared across genotypes. As shown in Figure 5F, larvae expressing either NFAT-A or NFAT-B moved significantly slower than control animals and thus covered a smaller distance in the allotted time (representative tracks from two independent animals are shown for each genotype). Moreover, as compared to a relatively straight trajectory in wild type animals, NFAT expressing larvae also displayed a greater degree of turning and “rolling”. From these recordings we concluded that NFAT expression in neurons results in lowered motor neuron firing that ultimately correlates with slow and unsteady locomotory patterns (quantitative analysis of crawling is shown in Figure 5G).

NFAT constrains activity-dependent pre-synaptic plasticity

Sustained alterations in the electrical activity of neurons is widely acknowledged to be a key regulator of long-term synaptic plasticity (Budnik et al., 1990; Chen and Tonegawa, 1997). Since our results show that NFAT reduces neuronal excitability, we hypothesized that increased neuronal NFAT would be sufficient to inhibit activity-driven synaptic changes at the larval NMJ. To test this idea we used two separate models that assay chronic (developmental) and acute forms of activity-dependent plasticity at this synapse.

The recently developed chronic plasticity model utilizes a combination of two mutations, comatose and Ca-P60A (called CK henceforth), that stably increases neuronal activity and activates the Ras/MAPK signaling cascade in larval motor neurons to produce larger larval NMJs (increased pre-synaptic bouton number) with stably elevated transmitter release as compared to similarly reared genetic controls (Freeman et al.; Hoeffer et al., 2003). Consistent with our prediction for NFAT, we discovered that motor neuron limited expression of either NFAT-A or NFAT-B using the OK6-GAL4 driver line (Sanyal, 2009) completely abolished increased synapse growth and transmitter release observed in CK animals (Figure 6). In fact, these two synaptic parameters were indistinguishable between control animals expressing NFAT and CK animals expressing NFAT, suggesting that NFAT function in pre-synaptic neurons is sufficient to inhibit activity-dependent plasticity in CK animals (p >0.18). Additionally, since OK6-GAL4 limits expression to larval motor neurons, these results also demonstrate cell autonomous roles for NFAT in Drosophila motor neurons in the regulation of neuronal excitability and plasticity.

Figure 6. NFAT constrains activity-dependent developmental plasticity.

A) Representative images of synapses showing increased NMJ size (bouton number) in a double mutant of comt and Ca-P60A (Kum) (CK) as compared to control synapses. This increase is completely inhibited by motor neuron restricted expression of NFAT, using the OK6-GAL4 driver line in a CK background. Expression of NFAT-A or NFAT-B by the OK6-GAL4 line in an otherwise wild type background results in a slightly reduced NMJ size. Scale bar = 25μm. B) Representative EJC traces showing that pre-synaptic transmitter release, also elevated in comt; Kum (CK) animals, is similarly limited by neuronal NFAT-B expression. Scale bar = 20nA; 200 ms. C) Quantification of bouton numbers shows that in comt; Kum mutants NMJs are larger than genetically relevant controls. Expression of either NFAT-A or NFAT-B in motor neurons using the motor neuron restricted OK6-GAL4 line leads to slightly reduced NMJ size. However, expression of NFAT in motor neurons in a CK background completely precludes the increase in NMJ size seen in CK animals. D) Quantification of synapse strength (mean EJC amplitude) demonstrating that NFAT expression also constrains activity-dependent increase in transmitter release seen in comt; Kum (CK) double mutant animals.

We further tested whether NFAT expression was capable of inhibiting acute activity-dependent bouton formation at the NMJ (Ataman et al., 2008). Spaced treatment of dissected larval neuro-muscular preparations with high potassium containing saline results in the formation of “ghost boutons”, pre-synaptic varicosities that lack opposing post-synaptic receptor clusters. These nascent boutons are believed to be the precursors of stable synaptic boutons, the formation of which is induced by increased neural activity. Under basal conditions, synapses typically contain 1–2 ghost boutons, but this number is increased several fold to 6–7 ghost boutons per synapse following spaced stimulation with high potassium containing saline. Expression of NFAT-A in motor neurons, however, completely precludes such activity-induced ghost bouton formation, such that the number of ghost boutons per synapse remains at baseline levels (Figure 7). Together with previous observations, these results strongly suggest that NFAT inhibits activity-dependent plasticity at the larval NMJ (Figure 7D).

Figure 7. NFAT inhibits acute activity-dependent plasticity at the larval NMJ.

A) Multiple spaced incubations of wild type larval fillet preparations with high potassium containing saline results in the formation of “ghost boutons” that are labeled by pre-synaptic markers such as HRP, but that do not contain corresponding post-synaptic receptors (labeled with Dlg) (arrows) B) Neuronal expression of NFAT completely precludes the formation of these ghost boutons upon stimulation with high potassium containing saline. C) Quantification of ghost boutons from ten independent preparations per genotype shows that while acutely increasing neural activity in a spaced fashion leads to the formation of more ghost boutons in a wild type animal, neuronal expression of NFAT-A prevents such an increase in ghost boutons. D) Model depicting how NFAT might dampen neuronal excitability thereby restricting activity-dependent synaptic plasticity. In this way it is in a position to antagonize positive regulators of plasticity such as AP-1 and CREB.

Discussion

NFAT-dependent cellular phenotypes in neurons are poorly understood. In this report we show that the single Drosophila NFAT homolog is expressed widely in the nervous system including motor neurons and using the established larval neuromuscular junction preparation, we demonstrate that pre-synaptic NFAT negatively regulates both synapse growth and transmitter release in a cell autonomous fashion. Synapse growth is regulated not by altered synaptic retraction or through neural cell adhesion molecules but involves stable modifications in the synaptic microtubule skeleton. Quite unexpectedly, we also find that neuronal expression of NFAT results in a decrement in neuronal excitability. Reduced neuronal excitability manifests as slower larval crawling suggesting behavioral outcomes of NFAT-mediated cellular phenotypes. These results provide evidence for the idea that specific plasticity-related transcriptional pathways can directly regulate neuronal excitability thereby exerting a strong influence on activity-dependent synaptic plasticity.

NFAT negatively regulates the number of boutons at the larval neuro-muscular synapse. As such, over-expression of either NFAT isoform in motor neurons leads to a smaller synapse with fewer boutons, while loss of NFAT produces more boutons as compared to control animals. Such bi-directional regulation of bouton numbers is also seen in the case of the transcription factor AP-1 and in instances where neural activity or cAMP signaling has been experimentally manipulated (Budnik et al., 1990; Davis et al., 1996; Mosca et al., 2005; Sanyal et al., 2002). In these cases, such changes are accompanied by alterations in the synaptic levels of the NCAM FasII. In general, synapse expansion requires local down-regulation, through internalization, of FasII and vice versa (Schuster et al., 1996a). However, our results suggest that synaptic FasII levels remain invariant following perturbation in NFAT expression pointing to different cellular pathways being regulated by NFAT. Synapse retraction, the withdrawal of pre-synaptic boutons after synaptic connections have been established, is also absent, suggesting that synapse growth per se is perhaps altered by NFAT. This idea is supported by the differences in MAP1B (Futsch) decorated microtubule structures that are observed in terminal synaptic boutons. NFAT over-expressing animals have many more closed stable microtubule loops while NFAT loss-of-function synapses have fewer. This phenotype is accompanied by modifications in the total expanse of the pre-synaptic arbor on the muscle cells. Interestingly, reducing the gene dosage of Futsch restores synaptic length. However, although Futsch is perhaps required for NFAT- and activity-dependent synaptic phenotypes, it is likely not a target of NFAT, since total Futsch protein levels remain unaltered following changes in NFAT expression (supplementary Figure 7). At this point we favor the idea that synaptic changes mediated by NFAT, including an effect on the number of Futsch positive terminal loops, are due to its effect on neuronal excitability (see below).

In addition to the number of pre-synaptic boutons, NFAT also regulates pre-synaptic transmitter release. Expression of either NFAT isoform strongly reduces the quantal content of release, while loss of NFAT increases it. Through EJC measurements under varying concentrations of extra-cellular calcium, we find that at relatively higher concentrations of extracellular calcium, the calcium dependence of release is inhibited by NFAT. This, in addition to no discernible changes in the number of active zones, might reflect an effect on either calcium entry through voltage gated calcium channels at the synapse, or on calcium sensing mechanisms within the boutons. Since the vast majority of studies have focused on a regulatory connection between calcium entry, calcineurin activation and NFAT nuclear translocation, the possibility that NFAT might itself regulate calcium entry and/or sensing is intriguing. It is also possible that a reduction in membrane resistance at the synaptic membrane, similar to that observed in the neuronal soma, might lead to reduced depolarization and less than normal calcium entry at the synapse. Future studies might discriminate between these possibilities by directly measuring calcium entry into synapses, genetically and biochemically testing interaction with calcium sensors such as synaptotagmin, subunits of calcium channels such as cacophony, and proteins that are known to regulate calcium dynamics in the synapse and influence neurotransmission such as frequenin and Cysteine-string Protein (csp) (Dason et al., 2009; Dawson-Scully et al., 2000; Kawasaki et al., 2000; Littleton et al., 1993).

What are the implications of reduced neuronal excitability and NFAT-dependent synaptic growth and transmitter release phenotypes on neuronal plasticity? To specifically answer this question, we used a recently developed model of pre-synaptic activity-dependent plasticity in the Drosophila larval preparation (Freeman et al.). We believe this model better represents plasticity pathways commonly observed in a variety of model systems, since it engages several known plasticity regulators such as the Ras/MAPK signaling module and the transcription factors Fos and CREB (Freeman et al.; Sanyal et al., 2002; Sweatt, 2001). In support of the notion that reduced neuronal excitability should inhibit activity-dependent plasticity, neuronal expression of NFAT completely limits synaptic plasticity seen in the CK model. Together with the observation that NFAT expression also attenuates rapid activity-dependent nascent bouton formation at this synapse, these findings support a scenario in which NFAT constrains synaptic plasticity potentially through attenuation of neural activity. Significantly, an NFAT-dependent alteration in neuronal excitability provides a unifying mechanism that satisfactorily explains NFAT’s role in growth factor mediated axonal outgrowth in cultured mouse embryonic neurons (Graef et al., 1999), both structural and functional plasticity of neuronal dendrites in Xenopus tadpole tectal neurons (Schwartz et al., 2009) and our own results with Drosophila motor neuron synapses. It is tempting to speculate that increasing NFAT activity in relevant neuronal circuits will also inhibit long-term behavioral adaptation. It is also possible that physiological levels of NFAT activity in individual neurons establish a threshold for synaptic growth and strengthening. Thus, when NFAT expression is increased in neurons (perhaps through the established pathways of calcium entry and calcineurin activation), the barrier for activity-dependent changes is elevated. In this way, the magnitude of NFAT activity in neurons might help filter out spurious, non-relevant fluctuations in neural activity from more salient, long-lasting variations such that only these are able to translate into persistent changes in neuronal function and behavior. While the downstream effects of NFAT on gene expression and precise mechanisms by which NFAT modulates neuronal excitability remain to be discovered, results from this study support the possibility that transcriptional regulation of neuronal excitability could be a more widely prevalent phenomenon during long-term plasticity and behavioral adaptation across species.

Experimental Methods

Fly stocks, rearing, transgenics and genetics

Drosophila strains were reared in standard corn meal – dextrose – yeast containing food at 25°C in controlled humidity incubators under a constant 12 hour light:dark cycle with the exception of experiments with comt; Kum mutants which were reared at 21°C (Freeman et al.). GAL4 lines elavC155, OK6, Mef2 and ShakB have been described previously (Lin et al., 1994; Sanyal, 2009; Sanyal et al., 2005; Takizawa et al., 2007). The two EP lines that were used to express either NFAT-A or NFAT-B, Df(1)ED7217, futschN94 and Df(1)Exel6239 were obtained from the Drosophila Stock Collection at Bloomington, the NFAT deletion allele (NFATΔAB) was from Dan Hultmark (Keyser et al., 2007), NFAT::GFP trap was from the FlyTrap collection (Buszczak et al., 2007), and the UAS-NFAT-RNAi line is from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Collection (VDRC). The UAS-NFAT[DN] transgene was generated by cloning the Rel-Homology Domain (RHD) of the NFAT gene into the pENTR-D Gateway cloning vector (Invitrogen Inc.) followed by insertion into the pTW Gateway compatible destination vector.

Antibodies, RNA in situs, immuno-histochemistry, western blotting and imaging

Larval dissection, staining and confocal microscopy were performed according to standard protocols (Franciscovich et al., 2008). Briefly, larvae were dissected in Ca2+ free HL3 ringer’s solution, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with primary antibody overnight, and followed by incubation in Alexa Fluor conjugated secondary antibody. For CNS staining, antibody incubation and washes were in a modified phosphate buffer (Sanyal, 2003). Mouse anti-Elav (partially purified IgG; DSHB, Iowa) was used at 1:100, mouse anti-syt (ascites, DSHB, Iowa) at 1:1000, rabbit anti-GFP (Molecular Probes) was used at 1:1000. Cy-5 conjugated Phalloidin (Jackson Laboratories) and all Alexa Fluor conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) were used at 1:200. An inverted 510 Zeiss LSM microscope was used for imaging. For quantitative fluorescence care was taken to prepare samples identically. Samples were imaged and analyzed double blind, and all imaging was interleaved such that control and experimental samples were imaged alternately on the same day. Confocal settings including black level (offset/contrast), gain, pixel dwell time and the number of iterative samplings for noise reduction were kept constant. Quantification of average fluorescence was done using ImageJ after background subtraction of 8-bit grayscale images. Mean FasII fluorescence intensity was divided by the mean HRP fluorescence intensity for each NMJ analyzed. This ratio was then plotted as a percentage of the control mean fluorescence ratio. NMJ size was counted as the number of Syt labeled boutons on muscles 6 and 7 (VL1 and VL2) in abdominal segment A2. Only one synapse was counted from one animal and at least 13 animals were counted for each genotype. Numbers were not normalized to muscle surface area since muscle sizes were independently determined to be comparable across genotypes (supplementary Figure 5). For Western blotting, adult Drosophila heads were isolated by snap freezing whole flies in liquid nitrogen and then using mechanical decapitation (vortexing) and separation with tissue isolation sieves. Adult heads or larval CNSs were added to 2x SDS protein extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, ph 6.8, 1.6% SDS, 8% glycerol, 4% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.04% xylene cyanol/bromophenol blue, including 2x Complete Mini Roche Protease Inhibitor) and homogenized using a motorized pestle. Protein lysates were separated on a 12% acrylamide gel. Proteins were visualized with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000) and developed with an ECL chemiluminescence kit (Amersham Biosciences). Anti-NFAT antibodies were raised in rabbits against a C-terminal portion of the protein comprising amino acids 989–1419 that was found to diverge most significantly from the vertebrate NFAT sequence. This partial protein was cloned downstream of an N-terminal GST tag in the vector pGS-21a (Genscript Inc.) and expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. The fusion protein was detected in inclusion bodies, which were purified and used for antibody production (Genscript Inc.). Bleeds were affinity purified against immobilized fusion protein and used for western blotting experiments (1:100).

Electrophysiology

Patch Clamp Recordings

Whole cell tight seal recordings were performed on motoneuron RP2 (MNISN1s) using external (mM: 118 NaCl, 2 NaOH, 2 KCl, 4 MgCl2, 4 CaCl2, 40 sucrose, 5 trehalose, 5 HEPES; pH 7.1; osmolality 305 mmol kg−1) and internal salines (mM 130 K-gluconate, 2 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 1 EGTA, 2 MgCl2, 0.1 CaCl2, 10 KOH; pH 7.2; osmolality 285 mmol kg−1) as described previously (Choi, 2004; Sandstrom, 2008). RP2 somata were visualized with ShakB-gal4 (Takizawa et al., 2007) driving membrane-bound GFP, using a parental strain that was homozygous w; ShakB-gal4; UAS-mCD8-GFP. When crossed to a line carrying a UAS-driven transgene, all progeny expressed both GFP and the transgene in RP2 (Figure 5A) and a small number of ventral neurons (Takizawa et al., 2007). For control experiments, ShakB-gal4;UAS-mCD8-GFP was crossed to wildtype. For recording, the CNS was removed from the larva, immobilized on a small chip of coverslip coated with poly-DL-ornithine (Sigma), and placed in a recording chamber under continuous superfusion. The sheath was softened and removed using a small-bore pipette filled with 0.1% collagenase type XIV (Sigma). Neurons were visualized with a 63X water-immersion objective, using Nomarski optics and GFP fluorescence (Olympus BX51WI; Olympus America, Center Valley, PA). Whole-cell recordings were performed with an AxoPatch 200B controlled by pClamp 8.2. Electrodes were fabricated to 5 – 10 Mohm from thick-walled capillary glass (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) on a vertical puller (Narishige PP-830, Narashige International USA, East Meadow, NY). F/I curves were measured in current clamp at -60 mV, while input resistance was measured from the slope of the I-V relation in voltage clamp at a holding potential of −70 mV.

Larval NMJ recordings

Two-electrode voltage clamp (TEVC) experiments were performed as described previously (Franciscovich et al., 2008; Sanyal et al., 2002). Briefly, larvae were dissected in normal HL3 ringer’s solution (Stewart et al., 1994) with 1 mM Ca2+. Both recording and current injecting electrodes were filled with 3 M KCl. Only those recordings were used where the voltage deflection following nerve stimulation could be clamped to within 5 mV. Muscle 6 (VL2) in abdominal segment A2 was used for all recordings and muscles were clamped at −70 mV. A train of 25 supra-threshold stimuli at 0.5 Hz was delivered in each experiment from which mean peak EJC values were obtained by averaging the last 20 traces. 8–10 separate animals were used for each genotype. A 2 minute continuous recording was used to measure mini frequency and amplitude. Traces were analyzed using Clampfit or Mini-Analysis programs (Synaptosoft). 8–10 separate animals were analyzed for each genotype. Quantal content was determined by dividing the mean EJC amplitude for a given synapse by the mean mEJC amplitude.

Larval locomotion assays

Larval locomotion was measured by videotaping individual larvae as they crawled on the surface of a 1% agar plate that did not contain any food source. Wandering third instar larvae were collected from standard culture vials at 25°C using a fine painting brush and added to a few drops of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at room temperature. Larvae were transferred individually onto the test plate and imaged for 30 seconds at a time. Each larva was imaged at least three times. For image analysis, each video file was converted to Quicktime and initial frames were deleted such that the file contained the last 20 seconds of recording. The entire image series was thresholded to increase contrast and larval locomotion was tracked across frames using the SpotTracker plugin for ImageJ. Three such 20 second recordings were summed to derive the total distance traveled in a 1 minute period. At least 10 larvae were analyzed for each genotype. Larval tracks were plotted using X and Y axis pixel coordinates from SpotTracker.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significances were determined using one-way ANOVA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge members of the Sanyal lab., Howard Nash, Veronica Rodrigues and Mani Ramaswami for useful discussions and insights. DJS thanks Howard Nash for space, material and intellectual support. We also thank the confocal microscopy facilities at the Cell Biology department at Emory University. We are grateful to Dan Hultmark for the NFATΔAB flies, and the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center for NFAT-RNAi flies. The anti-Syt (Kaushiki Menon and Kai Zinn) and anti-Elav (Gerald Rubin) antibodies were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by the University of Iowa, Department of Biological Sciences, Iowa City, IA 52242. This work was supported by grants from the URC, Emory University, a NARSAD Young Investigator Fellowship and grant DA027979-01 from NIDA to SS and the FIRST fellowship to AF.

Abbreviations

- NFAT

Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cells

- NMJ

Neuromuscular junction

- EJC

Evoked Junctional Current

- RHD

Rel-homology domain

- AP-1

Activating Protein-1

- MAP1B

Microtubule associated protein 1B

- FasII

Fasciclin II

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ataman B, Ashley J, Gorczyca M, Ramachandran P, Fouquet W, Sigrist SJ, Budnik V. Rapid activity-dependent modifications in synaptic structure and function require bidirectional Wnt signaling. Neuron. 2008;57:705–718. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartsch D, Casadio A, Karl KA, Serodio P, Kandel ER. CREB1 encodes a nuclear activator, a repressor, and a cytoplasmic modulator that form a regulatory unit critical for long-term facilitation. Cell. 1998;95:211–223. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81752-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunner A, O’Kane CJ. The fascination of the Drosophila NMJ. Trends Genet. 1997;13:85–87. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Budnik V, Zhong Y, Wu CF. Morphological plasticity of motor axons in Drosophila mutants with altered excitability. J Neurosci. 1990;10:3754–3768. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-11-03754.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buszczak M, Paterno S, Lighthouse D, Bachman J, Planck J, Owen S, Skora AD, Nystul TG, Ohlstein B, Allen A, Wilhelm JE, Murphy TD, Levis RW, Matunis E, Srivali N, Hoskins RA, Spradling AC. The carnegie protein trap library: a versatile tool for Drosophila developmental studies. Genetics. 2007;175:1505–1531. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.065961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen C, Tonegawa S. Molecular genetic analysis of synaptic plasticity, activity-dependent neural development, learning, and memory in the mammalian brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1997;20:157–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen L, Glover JN, Hogan PG, Rao A, Harrison SC. Structure of the DNA-binding domains from NFAT, Fos and Jun bound specifically to DNA. Nature. 1998;392:42–48. doi: 10.1038/32100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clipstone NA, Crabtree GR. Identification of calcineurin as a key signalling enzyme in T-lymphocyte activation. Nature. 1992;357:695–697. doi: 10.1038/357695a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole AJ, Saffen DW, Baraban JM, Worley PF. Rapid increase of an immediate early gene messenger RNA in hippocampal neurons by synaptic NMDA receptor activation. Nature. 1989;340:474–476. doi: 10.1038/340474a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins CA, DiAntonio A. Synaptic development: insights from Drosophila. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dason JS, Romero-Pozuelo J, Marin L, Iyengar BG, Klose MK, Ferrus A, Atwood HL. Frequenin/NCS-1 and the Ca2+-channel alpha1-subunit co-regulate synaptic transmission and nerve-terminal growth. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:4109–4121. doi: 10.1242/jcs.055095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis GW, Schuster CM, Goodman CS. Genetic dissection of structural and functional components of synaptic plasticity. III. CREB is necessary for presynaptic functional plasticity. Neuron. 1996;17:669–679. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawson-Scully K, Bronk P, Atwood HL, Zinsmaier KE. Cysteine-string protein increases the calcium sensitivity of neurotransmitter exocytosis in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6039–6047. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06039.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeZazzo J, Sandstrom D, de Belle S, Velinzon K, Smith P, Grady L, DelVecchio M, Ramaswami M, Tully T. nalyot, a mutation of the Drosophila myb-related Adf1 transcription factor, disrupts synapse formation and olfactory memory. Neuron. 2000;27:145–158. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eaton BA, Fetter RD, Davis GW. Dynactin is necessary for synapse stabilization. Neuron. 2002;34:729–741. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00721-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Estes PS, Roos J, van der Bliek A, Kelly RB, Krishnan KS, Ramaswami M. Traffic of dynamin within individual Drosophila synaptic boutons relative to compartment-specific markers. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5443–5456. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-17-05443.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flavell SW, Greenberg ME. Signaling mechanisms linking neuronal activity to gene expression and plasticity of the nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:563–590. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franciscovich AL, Mortimer AD, Freeman AA, Gu J, Sanyal S. Overexpression screen in Drosophila identifies neuronal roles of GSK-3 beta/shaggy as a regulator of AP-1-dependent developmental plasticity. Genetics. 2008;180:2057–2071. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.085555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freeman A, Bowers M, Mortimer AV, Timmerman C, Roux S, Ramaswami M, Sanyal S. A new genetic model of activity-induced Ras signaling dependent pre- synaptic plasticity in Drosophila. Brain Res. 1326:15–29. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.02.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graef IA, Mermelstein PG, Stankunas K, Neilson JR, Deisseroth K, Tsien RW, Crabtree GR. L-type calcium channels and GSK-3 regulate the activity of NF-ATc4 in hippocampal neurons. Nature. 1999;401:703–708. doi: 10.1038/44378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graef IA, Wang F, Charron F, Chen L, Neilson J, Tessier-Lavigne M, Crabtree GR. Neurotrophins and netrins require calcineurin/NFAT signaling to stimulate outgrowth of embryonic axons. Cell. 2003;113:657–670. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00390-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heckscher ES, Fetter RD, Marek KW, Albin SD, Davis GW. NF-kappaB, IkappaB, and IRAK control glutamate receptor density at the Drosophila NMJ. Neuron. 2007;55:859–873. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoeffer CA, Sanyal S, Ramaswami M. Acute induction of conserved synaptic signaling pathways in Drosophila melanogaster. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6362–6372. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-15-06362.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hope B, Kosofsky B, Hyman SE, Nestler EJ. Regulation of immediate early gene expression and AP-1 binding in the rat nucleus accumbens by chronic cocaine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5764–5768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaang BK, Kandel ER, Grant SG. Activation of cAMP-responsive genes by stimuli that produce long-term facilitation in Aplysia sensory neurons. Neuron. 1993;10:427–435. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90331-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kao SC, Wu H, Xie J, Chang CP, Ranish JA, Graef IA, Crabtree GR. Calcineurin/NFAT signaling is required for neuregulin-regulated Schwann cell differentiation. Science. 2009;323:651–654. doi: 10.1126/science.1166562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawasaki F, Felling R, Ordway RW. A temperature-sensitive paralytic mutant defines a primary synaptic calcium channel in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4885–4889. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-13-04885.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keller-Peck CR, Walsh MK, Gan WB, Feng G, Sanes JR, Lichtman JW. Asynchronous synapse elimination in neonatal motor units: studies using GFP transgenic mice. Neuron. 2001;31:381–394. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00383-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keyser P, Borge-Renberg K, Hultmark D. The Drosophila NFAT homolog is involved in salt stress tolerance. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;37:356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim SM, Kumar V, Lin YQ, Karunanithi S, Ramaswami M. Fos and Jun potentiate individual release sites and mobilize the reserve synaptic-vesicle pool at the Drosophila larval motor synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4000–4005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806064106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koh YH, Ruiz-Canada C, Gorczyca M, Budnik V. The Ras1-mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway regulates synaptic plasticity through fasciclin II-mediated cell adhesion. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2496–2504. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02496.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kraut R, Menon K, Zinn K. A gain-of-function screen for genes controlling motor axon guidance and synaptogenesis in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2001;11:417–430. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lahey T, Gorczyca M, Jia XX, Budnik V. The Drosophila tumor suppressor gene dlg is required for normal synaptic bouton structure. Neuron. 1994;13:823–835. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90249-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin DM, Fetter RD, Kopczynski C, Grenningloh G, Goodman CS. Genetic analysis of Fasciclin II in Drosophila: defasciculation, refasciculation, and altered fasciculation. Neuron. 1994;13:1055–1069. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Littleton JT, Stern M, Schulze K, Perin M, Bellen HJ. Mutational analysis of Drosophila synaptotagmin demonstrates its essential role in Ca(2+)-activated neurotransmitter release. Cell. 1993;74:1125–1134. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90733-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loh C, Carew JA, Kim J, Hogan PG, Rao A. T-cell receptor stimulation elicits an early phase of activation and a later phase of deactivation of the transcription factor NFAT1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3945–3954. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Macian F, Garcia-Cozar F, Im SH, Horton HF, Byrne MC, Rao A. Transcriptional mechanisms underlying lymphocyte tolerance. Cell. 2002;109:719–731. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00767-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marrus SB, DiAntonio A. Preferential localization of glutamate receptors opposite sites of high presynaptic release. Curr Biol. 2004;14:924–931. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mosca TJ, Carrillo RA, White BH, Keshishian H. Dissection of synaptic excitability phenotypes by using a dominant-negative Shaker K+ channel subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3477–3482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406164102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nguyen T, Di Giovanni S. NFAT signaling in neural development and axon growth. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2008;26:141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rao A, Luo C, Hogan PG. Transcription factors of the NFAT family: regulation and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:707–747. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roos J, Hummel T, Ng N, Klambt C, Davis GW. Drosophila Futsch regulates synaptic microtubule organization and is necessary for synaptic growth. Neuron. 2000;26:371–382. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rorth P. A modular misexpression screen in Drosophila detecting tissue-specific phenotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:12418–12422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruiz-Canada C, Ashley J, Moeckel-Cole S, Drier E, Yin J, Budnik V. New synaptic bouton formation is disrupted by misregulation of microtubule stability in aPKC mutants. Neuron. 2004;42:567–580. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00255-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruiz-Canada C, Budnik V. Synaptic cytoskeleton at the neuromuscular junction. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2006;75:217–236. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(06)75010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sandstrom DJ. Isoflurane depresses glutamate release by reducing neuronal excitability at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. J Physiol. 2004;558:489–502. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.065748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanyal S. Genomic mapping and expression patterns of C380, OK6 and D42 enhancer trap lines in the larval nervous system of Drosophila. Gene Expr Patterns. 2009;9:371–380. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanyal S, Consoulas C, Kuromi H, Basole A, Mukai L, Kidokoro Y, Krishnan KS, Ramaswami M. Analysis of conditional paralytic mutants in Drosophila sarco-endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase reveals novel mechanisms for regulating membrane excitability. Genetics. 2005;169:737–750. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.031930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sanyal S, Ramaswami M. Activity-dependent regulation of transcription during development of synapses. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2006;75:287–305. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(06)75013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanyal S, Sandstrom DJ, Hoeffer CA, Ramaswami M. AP-1 functions upstream of CREB to control synaptic plasticity in Drosophila. Nature. 2002;416:870–874. doi: 10.1038/416870a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schuster CM, Davis GW, Fetter RD, Goodman CS. Genetic dissection of structural and functional components of synaptic plasticity. I. Fasciclin II controls synaptic stabilization and growth. Neuron. 1996a;17:641–654. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schuster CM, Davis GW, Fetter RD, Goodman CS. Genetic dissection of structural and functional components of synaptic plasticity. II. Fasciclin II controls presynaptic structural plasticity. Neuron. 1996b;17:655–667. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwartz N, Schohl A, Ruthazer ES. Neural activity regulates synaptic properties and dendritic structure in vivo through calcineurin/NFAT signaling. Neuron. 2009;62:655–669. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stewart BA, Atwood HL, Renger JJ, Wang J, Wu CF. Improved stability of Drosophila larval neuromuscular preparations in haemolymph-like physiological solutions. J Comp Physiol [A] 1994;175:179–191. doi: 10.1007/BF00215114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sweatt JD. The neuronal MAP kinase cascade: a biochemical signal integration system subserving synaptic plasticity and memory. J Neurochem. 2001;76:1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takizawa E, Komatsu A, Tsujimura H. Identification of common excitatory motoneurons in Drosophila melanogaster larvae. Zoolog Sci. 2007;24:504–513. doi: 10.2108/zsj.24.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wagh DA, Rasse TM, Asan E, Hofbauer A, Schwenkert I, Durrbeck H, Buchner S, Dabauvalle MC, Schmidt M, Qin G, Wichmann C, Kittel R, Sigrist SJ, Buchner E. Bruchpilot, a protein with homology to ELKS/CAST, is required for structural integrity and function of synaptic active zones in Drosophila. Neuron. 2006;49:833–844. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wayman GA, Impey S, Marks D, Saneyoshi T, Grant WF, Derkach V, Soderling TR. Activity-dependent dendritic arborization mediated by CaM-kinase I activation and enhanced CREB-dependent transcription of Wnt-2. Neuron. 2006;50:897–909. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wong RO, Ghosh A. Activity-dependent regulation of dendritic growth and patterning. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:803–812. doi: 10.1038/nrn941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.