Cecal volvulus is a rare cause of bowel obstruction that carries significant mortality. A high index of suspicion is needed to avoid delay in definitive treatment.

Keywords: Cecal volvulus, Laparoscopic nephrectomy

Abstract

Cecal volvulus is a rare cause of bowel obstruction that carries a high mortality. Recent surgery is known to be a risk factor for the development of cecal volvulus. We present a case of cecal volvulus following laparoscopic nephrectomy and renal transplantation.

INTRODUCTION

Cecal volvulus is axial twisting involving the cecum, ascending colon, and terminal ileum, resulting in a closed loop obstruction of the cecum. If persistent, vascular compromise will develop. It is an infrequent cause of bowel injury, but carries a high mortality of up to 40%.1 The high mortality rate is likely due to the delay in diagnosis and treatment.

Previous surgery is known to be a risk factor for the development of a cecal volvulus with reports of up to 68% of patients having previous abdominal surgery.2,3 We present the first reported case of cecal volvulus following laparoscopic nephrectomy.

CASE REPORT

A 63-year-old female with chronic kidney disease secondary to polycystic kidney disease was evaluated and found to be a suitable candidate for renal transplantation. Due to the large size of her kidney (Figure 1), bilateral nephrectomy was recommended. Although she was on hemodialysis, she was reluctant to have both kidneys removed. She underwent hand-assisted laparoscopic right nephrectomy that was complicated by persistent ascites and prolonged postoperative ileus.

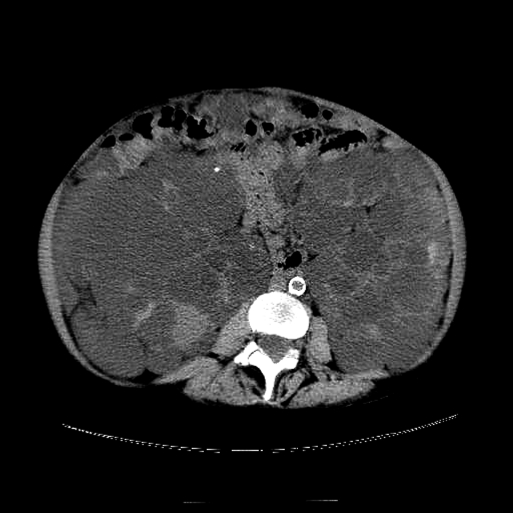

Figure 1.

Computed tomography showing grossly enlarged kidneys consistent with polycystic kidney disease.

Six weeks after her nephrectomy, she underwent deceased donor renal transplantation into her right iliac fossa. Again, her postoperative course was complicated by an ileus. A week after her transplantation, she was discharged home with a well-functioning renal allograft.

One month after transplantation, she complained of abdominal pain and obstipation of 1-day duration. Examination was significant for abdominal distension with a palpable left polycystic kidney and polycystic liver. In addition, there was tenderness and tympany over the right abdomen without discrete peritoneal signs. She was admitted and radiologic studies, including plain abdominal films and computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, were performed. Imaging showed features consistent with ileus. A day later, she reported the passage of flatus, but her abdominal examination and abdominal films remained unchanged. A colonoscopy was performed and described as “technically difficult,” and the cecum could not be reached. The visualized colon was otherwise unremarkable. Failure of her symptoms to resolve prompted a gastrograffin enema yielding the diagnosis of a cecal volvulus (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Gastrograffin enema showing characteristic “beak” at distal end of cecal volvulus (arrow).

Laparotomy performed 3 days after presentation confirmed the presence of a cecal volvulus. This was associated with a small perforation at the torsion point. The patient underwent a right hemicolectomy with primary ileocolic anastomosis. Three weeks after her colectomy, the patient was transferred to an inpatient rehabilitation facility. Throughout her hospitalization, she demonstrated excellent renal function.

DISCUSSION

Cecal volvulus is a rare cause of intestinal obstruction. Volvulus of the cecum is second to the sigmoid among colonic volvulus. The incidence ranges from 2.8 to 7.1 per million people per year.1 There is a female preponderance with a median age of occurrence in the sixth decade of life.2

Cecal volvulus occurs when a mobile cecum twists along its mesenteric axis, resulting in a closed loop obstruction of the cecum. Embryologically, this occurs when there is inadequate fixation of the right colon to the retroperitoneum. Cecal mobility is not uncommon, with up to 25% of cadavers found to have a mobile cecum.1 Besides a mobile cecum, an additional factor is required for the development of a cecal volvulus. Reported risk factors include previous abdominal surgery, pregnancy, high fiber intake, chronic constipation, adynamic ileus, and distal bowel obstruction.2,3

Symptoms of a cecal volvulus include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain with distension, diarrhea, constipation, and obstipation.2,3 The symptoms may suggest recurrent intermittent acute bowel obstruction or persistent bowel obstruction. On clinical findings alone, it is often difficult to distinguish cecal volvulus from small bowel obstruction, constipation, adynamic ileus, or other causes of colonic obstruction.

Radiologic imaging may provide clues in diagnosing a cecal volvulus. A plain abdominal radiograph may reveal either a collapsed or dilated cecum errant from the right iliac fossa.3 Its accuracy in diagnosing cecal volvulus ranges from 4% to 50%.3 Computed tomography may identify the “coffee bean,” “bird beak,” or “whirl” sign to suggest acute cecal volvulus.4 Contrast enema may be most helpful in confirming the diagnosis of a cecal volvulus with demonstration of a spiralling or beaking of the mucosa at the site of torsion.3 The accuracy of contrast enema for diagnosing cecal volvulus approaches 90%.2

Treatment of cecal volvulus involves detorsion of the volvulus. This can be accomplished with contrast or air enema, colonoscopy, or surgery. Unless fixation of the mobile cecum is performed, the cecum will remain mobile and is associated with a recurrence rate of 11%.2 If the cecum is viable, a cecostomy tube may be considered. The cecostomy tube anchors the cecum, rendering it im-mobile and allows venting of the dilated colon. Unfortunately, this requires opening of an unprepped bowel and is associated with an increased risk of infectious complications.3,5 Recurrence of volvulus with cecostomy tube placement alone has been reported.1 Cecopexy with fixation of the mobile cecum to the parietal peritoneum with multiple nonabsorbable sutures does not require an enterotomy but has a recurrence rate as high as 40%.5 No recurrence has been reported following cecopexy with cecostomy tube placement. When there is questionable viability of the cecum, obvious strangulation, or perforation, an ileocolectomy must be performed. The decision to perform a primary anastomosis versus ileostomy is determined by the stability of the patient and amount of contamination.

A mobile cecum is required for the development of cecal volvulus. It is likely our patient developed a mobile cecum following her initial surgery. Our patient had a transabdominal hand-assisted laparoscopic right nephrectomy, which required mobilization of the entire right colon. The presence of ascites postoperatively likely prevented the right colon from adhering back onto the retroperitoneum. She then underwent renal transplantation with the kidney placed in an extraperitoneal location. Although abdominal surgery is a risk factor, cecal volvulus has been reported following retroperitoneal surgery.6–8 Postoperative ileus following renal transplantation is not uncommon. Retrospectively, the presence of ileus in our patient may have been due to mobile cecum syndrome.1

At her acute presentation, multiple diagnostic tests were obtained. Because early radiologic tests suggested an ileus, we were falsely reassured. Colonoscopy was obtained to evaluate for a colonic obstruction but was inconclusive because the entire colon was not visualized. Gastrografin enema performed due to the incomplete colonoscopy was successful in providing the diagnosis of cecal volvulus.

Upon diagnosis of the cecal volvulus, the patient was promptly taken to the operating suite. The presence of a perforation necessitated a colectomy. An ileocolic anastomosis was performed as the patient remained stable, and there was no gross contamination. Despite the delay in diagnosis and treatment, this patient did well postoperatively.

CONCLUSION

Cecal volvulus is a rare cause of bowel obstruction that carries a high mortality. As our case demonstrates, symptoms are difficult to distinguish from other causes of bowel obstruction. Therefore, a high index of suspicion is needed to avoid delay in definitive treatment.

Our patient is unique in that her mobile cecum is likely acquired. Laparoscopic surgery to retroperitoneal structures requires the mobilization of the colon. Laparoscopic surgery is known to have less adhesion formation.9,10

Unless the colon adheres back onto the retroperitoneum, the colon will remain mobile and at risk for volvulus. A literature review has identified multiple cases of volvulus following laparoscopic procedures.11–14 Whether the incidence of volvulus has increased as more laparoscopic procedures are being performed has yet to be determined. Certainly, in patients with a history of a laparoscopic procedure who present with bowel obstruction, colonic volvulus should be considered early to avoid the high mortality associated with delay.

Contributor Information

Mary Eng, Department of Surgery, Division of Transplantation, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky, United States..

Kadiyala Ravindra, Department of Surgery, Division of Transplantation, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky, United States..

References:

- 1. Consorti ET, Liu TH. Diagnosis and treatment of caecal volvulus. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:772–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ballantyne GH, Brandner MD, Beart RW, Ilstrup DM. Volvulus of the colon: Incidence and mortality. Ann Surg. 1985;202:83–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Mara CS, Wilson TH, Stonesifer GL, Cameron JL. Cecal volvulus: Analysis of 50 patients with long-term follow-up. Ann Surg. 1979;189:724–731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moore CJ, Corl FM, Fishman EK. CT of cecal volvulus: unraveling the image. AJR. 2001;177:95–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Madiba TE, Thomson SR. The management of cecal volvulus. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45(2):264–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khan SA, Desai PG, Siddarth P, Smith N. Volvulus of cecum following simple nephrectomy. Urol Int. 1985;40:1–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Etheredge EE, Martz M, Anderson CB. Volvulus of the cecum following transplant donor nephrectomy. Surgery. 1977;82(5):764–767 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guerra EE, Nghiem DD. Posttransplant cecal volvulus. Transplantation. 1990;50(4):721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gutt CN, Oniu T, Schemmer P, Mehrabi A, Buchler MW. Fewer adhesions induced by laparoscopic surgery? Surg Endosc. 2004;18:898–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Szabo G, Miko I, Nagy P, Brath E, Peto K, Furka I, Gamal EM. Adhesion formation with open versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an immunologic and histologic study. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:252–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bariol SV, McEwen HJ. Caecal volvulus after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Aust NZ J Surg. 1999;69:79–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ferguson L, Higgs Z, Brown S, McCarter D, McKay C. Intestinal volvulus following laparoscopic surgery: A literature review and case report. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2008;18(3):405–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McIntosh SA, Ravichandran D, Wilmink ABM, Baker A, Purushotham AD. Cecal volvulus occurring after laparoscopic appendectomy. JSLS. 2001;5:317–318 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ulloa SA, Ramirez LO, Ortiz VN. Cecal volvulus after laparoscopic liver biopsy. Bol Asoc Med P R. 1997;89(10–12):195–196 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]