Abstract

The abundance of microbes in soil is thought to be strongly influenced by plant productivity rather than by plant species richness per se. However, whether this holds true for different microbial groups and under different soil conditions is unresolved. We tested how plant species richness, identity and biomass influence the abundances of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), saprophytic bacteria and fungi, and actinomycetes, in model plant communities in soil of low and high fertility using phospholipid fatty acid analysis. Abundances of saprophytic fungi and bacteria were driven by larger plant biomass in high diversity treatments. In contrast, increased AMF abundance with larger plant species richness was not explained by plant biomass, but responded to plant species identity and was stimulated by Anthoxantum odoratum. Our results indicate that the abundance of saprophytic soil microbes is influenced more by resource quantity, as driven by plant production, while AMF respond more strongly to resource composition, driven by variation in plant species richness and identity. This suggests that AMF abundance in soil is more sensitive to changes in plant species diversity per se and plant species composition than are abundances of saprophytic microbes.

Keywords: AMF, biodiversity, soil, ecosystem functioning, grassland, phospholipid fatty acid

1. Introduction

Many studies have explored effects of plant species or functional group richness on aboveground primary production [1]. However, our understanding of how plant diversity influences belowground properties remains limited, and those studies that have investigated this issue present conflicting results [2]. Ample studies report positive effects of plant diversity on net primary production [1], which leads to an increased quantity and diversity of resources entering the soil, potentially stimulating the abundance of decomposer organisms [2]. However, whether such effects are driven by changes in plant productivity or by species identity is unclear: some studies show that abundances of decomposer fungi and bacteria can be stimulated by larger plant productivity in high diversity treatments [3], whereas others indicate that abundances of decomposer microbes are primarily affected by the identity of plant species [4,5] or by species richness per se [6]. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) are known to respond strongly to individual plant species [7], but their relationship to plant species richness is unclear. Plant species richness can stimulate AMF abundance in soil via larger plant biomass [8], although in a cross-site study Hedlund et al. [4] found that AMF biomass related positively to plant species richness and negatively to plant biomass, or showed no relationship to plant species richness depending on field site.

The aim of this study was to test how different groups of soil microbes, including AMF and saprophytic microflora, respond to plant species richness, identity and productivity, and to assess whether these responses vary depending on soil fertility. This was done by assessing the abundance of their specific phospholipid fatty acids (PLFAs) in model grassland communities in which plant diversity and soil fertility were found to increase total plant and microbial biomass [9]. We hypothesized that: (i) AMF abundance, being obligate plant symbionts, responds more strongly to plant species identity than abundances of saprophytic soil microbes, including decomposer bacteria and fungi; and (ii) abundances of saprophytes and AMF increase with larger plant biomass, which increases the quantity of carbon input to soil, but not with species richness per se.

2. Material and methods

(a). Experimental design

Model plant communities were established in outdoor mesocosms (36×36 cm, 30 cm deep) filled with 20.8 l of soil on top of a 10-cm layer of limestone chippings. We used two soils of contrasting fertility, collected from two adjacent grasslands of contrasting long-term fertilizer management, hereafter referred to as high- and low-fertility soil (see [9]), at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne Farm (54°1′ N, 0°23′ W).

The experiment comprised 128 mesocosms. Half of these contained low-fertility soil, the other half high-fertility soil, and vegetation treatments for each of the two soils included: four unplanted mesocosms, 24 monocultures (four replicates per plant species), 24 mixtures of two plant species, eight mixtures of three species and four mixtures of six plant species arranged in a randomized design with four replicated blocks. Each planted mesocosm received 36 plant individuals. The plant species were taken from a pool of six common grassland species, and per level of species richness, each species was present in an equal number of mesocosms [9]. Aboveground and belowground biomass were measured after two growing seasons at the end of August. Shoots were clipped above the soil surface, and root biomass was measured by extracting all roots, by sieving (2.6-mm mesh) and by handpicking, contained in five soil cores (34 mm diameter, full mesocosm depth) collected immediately after clipping. Shoots and roots were dried at 70°C and weighed. Subsamples of the sieved soil (average moisture content 23%), were immediately frozen at −80°C and freeze dried for PLFA analysis.

(b). Soil microbial composition and abundance

Soil microbial community composition was assessed using the PLFA protocol described in Harrison & Bardgett [10]. The PLFA C16 : 1ω5 was used as an indicator for AMF abundance, and although the specificity of this PLFA is limited, it is commonly used to indicate changes in AMF abundance in soil, especially when unplanted soil is used as a reference [8,11]; C18 : 2ω6,9 and C18 : 1ω9 were used for abundance of saprophytic fungi, C18 : 0(10Me) for abundance of actinomycetes, PLFAs C16 : 1ω7c, C16 : 1ω7t, C17 : 0cy, C18 : 1ω7 and C19 : 0cy for abundance of Gram-negative bacteria and PLFAs C15 : 0i, C15 : 0ai, C16 : 0i, C17 : 0i and C17 : 0ai for Gram-positive bacteria and the PLFAs C15:0 and C17:0 as additional markers for bacterial abundance [12].

(c). Data analysis

The effect of soil fertility, plant species richness (or identity for comparison between monocultures) and their interaction on PLFA abundances of actinomycetes, AMF and saprophytic fungi and bacteria were tested by MANOVAs and because these showed significant treatment effects by subsequent ANOVAs for the different PLFA groups. To separate effects of plant species richness from that of plant biomass (aboveground + belowground), plant biomass was included as first (co-)factor in ANCOVA with soil fertility, plant species richness and their interaction as other explanatory factors. PLFA abundance of AMF was square root transformed prior to analysis to obtain equal variances across levels of plant species richness. Relationships between AMF and shoot biomass of each plant species across levels of plant species richness and soil fertility were analysed using multiple linear regression and the effect of absence/presence of Anthoxantum odoratum per species richness level by t-tests. Differences between treatments of plant species richness were determined with conservative post hoc tests (Tukey for unequal N and Bonferroni). Data were analysed with STATISTICA v. 8 (StatSoft).

3. Results

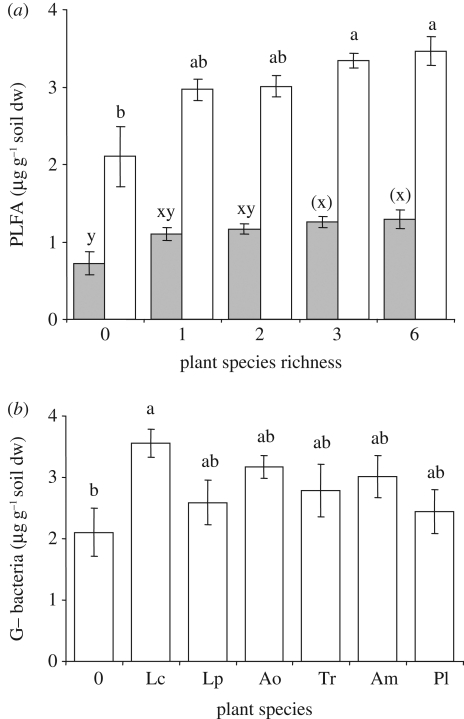

Microbial PLFA abundances were significantly affected by soil fertility (table 1, MANOVA), owing to abundances of non-mycorrhizal fungi, actinomycetes and Gram-negative bacteria, which were greater in high- than in the low-fertility soil (table 1, ANOVA). The separate ANOVAs also indicated effects of plant species richness on the abundances of AMF, non-mycorrhizal fungi and Gram-negative bacteria (table 1), which all tended to increase with plant species richness (figures 1a and 2a). After accounting for significant effects of plant biomass (figure S1a,b in the electronic supplementary material) on non-mycorrhizal fungi (ANCOVA F1,114 = 8.73, p < 0.01) and Gram-negative bacteria (ANCOVA F1,114 = 12.25, p < 0.001), plant species richness no longer affected abundances of non-mycorrhizal fungi (ANCOVA F4,114 = 1.85, p = 0.12) or Gram-negative bacteria (F4,114 = 1.99, p = 0.10). In contrast, abundance of AMF was strongly affected by plant species richness (ANCOVA F4,114 = 3.40, p = 0.011) when influence of vegetation biomass, which itself had no significant impact on AMF (ANCOVA F1,114 = 0.32, p = 0.58; figure S1c in the electronic supplementary material), was taken into account.

Table 1.

F- and p-values of MANOVA and ANOVA testing effects of soil type (S), plant species richness (P) or identity of monocultures (ID) and their interaction (S × P or S × ID) on PLFA abundance of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), non-mycorrhizal fungi (other fungi), G− and G+ bacteria and actinomycetes.

| MANOVA |

ANOVA |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-values | d.f. | Wilks lambda | d.f. | AMF | other fungi | G− bacteria | G+ bacteria | actinomycetes |

| soil type (S) | 5113 | 5.65 (p < 0.001) | 1117 | 0.71 (p = 0.40) | 17.69 (p < 0.0001) | 8.86 (p = 0.003) | 3.37 (p = 0.07) | 13.22 (p = 0.0004) |

| plant species richness (P) | 20 376 | 1.11 (p = 0.33) | 4117 | 3.04 (p = 0.020) | 2.52 (p = 0.045) | 3.55 (p = 0.009) | 1.16 (p = 0.33) | 0.97 (p = 0.43) |

| S × P | 20 376 | 0.62 (p = 0.90) | 4117 | 0.55 (p = 0.70) | 0.21 (p = 0.93) | 0.57 (p = 0.68) | 0.05 (p = 0.99) | 0.40 (p = 0.81) |

| soil type (S) | 537 | 7.90 (p < 0.0001) | 141 | 1.54 (p = 0.22) | 11.97 (p = 0.001) | 11.92 (p = 0.001) | 2.10 (p = 0.15) | 17.76 (p = 0.001) |

| plant species identity (ID) | 30 150 | 2.49 (p = 0.0002) | 641 | 2.64 (p = 0.030) | 1.12 (p = 0.37) | 2.48 (p = 0.039) | 0.86 (p = 0.54) | 0.76 (p = 0.61) |

| S × ID | 30 150 | 0.89 (p = 0.63) | 641 | 0.47 (p = 0.83) | 0.05 (p = 1) | 0.48 (p = 0.82) | 0.38 (p = 0.89) | 0.26 (p = 0.95) |

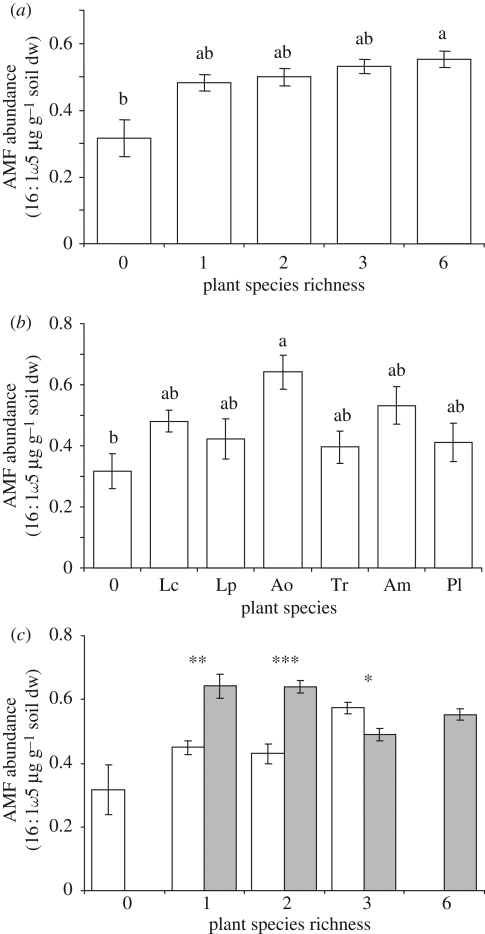

Figure 1.

Abundance of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) in relation to plant species (a) richness, (b) monoculture identity, and (c) absence/presence of Anthoxanthum odoratum (Ao) across levels of plant species richness. Lp, Lolium perenne; Ao, Anthoxanthum odoratum; Pl, Plantago lanceolata; Am, Achillea millefolium; Tr, Trifolium repens; Lc, Lotus corniculatus; 0, bare soil. Bars: means ± s.e., bars not sharing the same letter are significantly different at p < 0.05. Significance within species richness level: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Open bars, −Ao; filled bars, +Ao.

Figure 2.

Abundance of non-mycorrhizal soil fungi and Gram-negative soil bacteria PLFAs in relation to plant species (a) richness and (b) identity in monocultures. x-axis labels as in figure 1. Bars: means ± s.e., bars not sharing the same letter are significantly different at p < 0.05 or for letters in parentheses ( ) p < 0.10. Filled bars, fungi; open bars, Gram-negative bacteria.

PLFA abundances in monocultures and unplanted soil were significantly affected by plant species identity and soil fertility (table 1, MANOVA). Non-mycorrhizal fungi, Gram-negative bacteria and actinomycetes responded to soil fertility, while plant species identity affected AMF and Gram-negative bacteria (table 1, ANOVA). The abundance of AMF was greatest in soil of A. odoratum, and that of Gram-negative bacteria in Lotus corniculatus (figures 1b and 2b). The influence of A. odoratum on AMF was also notable in species mixtures (figure 1c) and multiple linear regression across all levels of plant species richness and soil fertility between AMF-specific PLFA C16 : 1ω5 and shoot biomass of individual plant species (F6,120 = 5.36, r2 = 0.21, p < 0.001) revealed a positive relationship between AMF abundance and shoot biomass of A. odoratum (β = 0.48, p < 0.0001; figure S2 in the electronic supplementary material).

4. Discussion

In line with earlier studies, we found positive effects of plant species richness on PLFA abundances [3,8], but in contrast plant biomass could only explain this response for saprophytic soil microbes and not for AMF. We found that AMF respond more strongly to resource composition, driven by variation in plant species richness and identity, probably because AMF live on living plants unlike the saprophytes that decompose dead organic matter. The discrepancy between the studies could be due to the use of different plant species and their specific effects, as found in our study; however, specific plant species effects on soil microbes were not tested in the aforementioned studies. The impact of specific plant species on AMF abundance in mixed plant communities may also depend on their abundance and/or interactions with other plant species, as indicated by the less pronounced effect of A. odoratum on AMF in three-species mixtures. Overall, our results are in line with responses of AMF diversity to grassland plant communities, in that this measure was greater in plant species mixtures than in monocultures and independent of plant productivity [13].

Collectively, our findings suggest that, irrespective of soil fertility, the abundance of AMF in soil is under strong direct influence of plant species identity and composition by responding to specific plant characteristics, while the abundance of decomposer soil fungi, bacteria and actinomycetes is primarily driven by plant production, and hence mostly responsive to the quantity of plant inputs to soil. These findings suggest that AMF are more sensitive to plant species losses than saprophytic soil biota, and demonstrate the need for more detailed studies of functionally different groups of soil microbes as they may be driven differentially by specific plant community attributes.

Acknowledgements

We thank BBSRC for funding, William Taylor, Kate Harrison, Will Mallott for practical assistance and the referees for helpful comments.

References

- 1.Balvanera P., Pfisterer A. B., Buchmann N., He J. S., Nakashizuka T., Raffaelli D., Schmid B. 2006. Quantifying the evidence for biodiversity effects on ecosystem functioning and services. Ecol. Lett. 9, 1146–1156 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00963.x (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00963.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bardgett R. D., Wardle D. A. 2010. Aboveground–belowground linkages: biotic interactions, ecosystem processes, and global change. Oxford Series in Ecology and Evolution. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zak D. R., Holmes W. E., White D. C., Peacock A. D., Tilman D. 2003. Plant diversity, soil microbial communities, and ecosystem function: are there any links? Ecology 84, 2042–2050 10.1890/02-0433 (doi:10.1890/02-0433) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hedlund K., et al. 2003. Plant species diversity, plant biomass and responses of the soil community on abandoned land across Europe: idiosyncracy or above-belowground time lags. Oikos 103, 45–58 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12511.x (doi:10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12511.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wardle D. A., Bonner K. I., Barker G. M., Yeates G. W., Nicholson K. S., Bardgett R. D., Watson R. N., Ghani A. 1999. Plant removals in perennial grassland: vegetation dynamics, decomposers, soil biodiversity, and ecosystem properties. Ecol. Monogr. 69, 535–568 10.1890/0012-9615(1999)069[0535:PRIPGV]2.0.CO;2 (doi:10.1890/0012-9615(1999)069[0535:PRIPGV]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenhauer N., et al. 2010. Plant diversity effects on soil microorganisms support the singular hypothesis. Ecology 91, 485–496 10.1890/08-2338.1 (doi:10.1890/08-2338.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bever J. D., Morton J. B., Antonovics J., Schultz P. A. 1996. Host-dependent sporulation and species diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in a mown grassland. J. Ecol. 84, 71–82 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung H. G., Zak D. R., Reich P. B., Ellsworth D. S. 2007. Plant species richness, elevated CO2, and atmospheric nitrogen deposition alter soil microbial community composition and function. Glob. Change Biol. 13, 980–989 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01313.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01313.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Deyn G. B., Quirk H., Yi Z., Oakley S., Ostle N. J., Bardgett R. D. 2009. Vegetation composition promotes carbon and nitrogen storage in model grassland communities of contrasting soil fertility. J. Ecol. 97, 864–875 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01536.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01536.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison K. A., Bardgett R. D. 2010. Influence of plant species and soil conditions on plant-soil feedback in mixed grassland communities. J. Ecol. 98, 384–395 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01614.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01614.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsson P. A. 1999. Signature fatty acids provide tools for determination of the distribution and interactions of mycorrhizal fungi in soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 29, 303–310 10.1111/j.1574-6941.1999.tb00621.x (doi:10.1111/j.1574-6941.1999.tb00621.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patra A. K., Le Roux X., Grayston S. J., Loiseau P., Louault F. 2008. Unraveling the effects of management regime and plant species on soil organic carbon and microbial phospholipid fatty acid profiles in grassland soils. Bioresour. Technol. 99, 3545–3551 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.07.051 (doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2007.07.051) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson D., Vandenkoornhuyse P. J., Leake J. R., Gilbert L. A., Booth R. E., Grime J. P., Young J. P. W., Read D. J. 2004. Plant communities affect arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal diversity and community composition in grassland microcosms. New Phytol. 161, 503–516 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00938.x (doi:10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00938.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]