Abstract

Shotgun proteomics has been used extensively for characterization of a number of proteomes. High resolution Fourier transform mass spectrometry (FTMS) has emerged as a powerful tool owing to its high mass accuracy and resolving power. One of its major limitations, however, is that the confidence level of peptide identification and sensitivity cannot be maximized simultaneously. Although it is generally assumed that higher resolution is better for peptide identifications, the precise effect of varying resolution as a parameter on peptide identification has not yet been systematically evaluated. We used the Escherichia coli proteome and a standard 48 protein mix to study the effect of different resolution parameters on peptide identifications in the setting of a shotgun proteomics experiment on an LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer. We observed a higher number of peptide-spectrum matches (PSMs) whenever the MS scan was carried out by FT and the MS/MS in the ion-trap (IT) with the maximum PSMs obtained at an MS resolution of 30,000. In contrast, when samples were analyzed by FT for both MS and MS/MS, the number of PSMs was significantly lower (~40% as compared to FT-IT experiments) with the maximum PSMs obtained when both the MS and MS/MS resolution were set to 15,000. Thus, a 15K-15K resolution setting may provide the best compromise for studies where both speed and accuracy such as high-throughput post-translational analysis and de novo sequencing are important. We hope that our study will allow researchers to choose between different resolution parameters to achieve their desired results from proteomic analyses.

Keywords: FTMS, duty cycle, E. coli proteome, PSM

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, shotgun proteomics has become one of the most popular techniques in proteomics. Most recently, the LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer [1], one of high resolution Fourier transform mass spectrometers (FTMS), has been applied to a diverse set of experiments ranging from metabolomic analyses to clinical proteomics. [2] In an Orbitrap analyzer, the ions can be detected with a high mass accuracy of less than 2 parts per million (ppm) using internal standards and 5 ppm with external calibration. [3] The maximum resolving power exceeds 100,000 at 400 m/z [3], with additional features such as a wide dynamic range, fast duty cycle, and high sensitivity. These advantages allow complex peptide mixtures to be analyzed in greater depth with high confidence [4–6].

The various fragmentation methods available in LTQ-Orbitrap include collision induced dissociation (CID), electron transfer dissociation (ETD) [7] and relatively newer methods such as pulsed-Q-dissociation (PQD) [8], high energy C-trap dissociation and higher energy collision dissociation (HCD) [9]. In most shotgun proteomic experiments, the important goal is to achieve a deeper proteome coverage which can be accomplished by the above mentioned fragmentation methods. In the recent years, there have also been several efforts to combine two fragmentation methods such as ECD-CID [10], CID-ETD [11], CID-PQD [12] and CID-HCD [13] to maximize the number of identified and quantitated peptides. The most popular method, however, for obtaining peptide sequence information remains CID based fragmentation. In MS-based proteomic analyses, tandem mass spectrometry is one of the conventional methods in which gaseous peptide ions are analyzed in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) [14] mode where one MS scan for detecting precursors is followed by data dependent MS/MS scans for fragments generated by CID. The combined information from MS and MS/MS scans is used to search tandem spectra against protein sequence database using search algorithms such as Mascot [15], SEQUEST [16], OMSSA [17], X!Tandem [18] and Spectrum Mill [11].

There are a multitude of factors that directly affect the quality and quantity of the MS/MS spectra, which in turn influence the peptide identifications in proteomic analyses. Given the popularity of the LTQ mass spectrometer and the hybrid LTQ-FTMS, it is essential to systematically optimize the factors controlling the mass spectrometer. Although a number of parameters that could influence the peptide identification rate have been studied including signal threshold of precursors for data dependent scans [19] and dynamic exclusion duration [20], the impact of varying resolution parameters has not been systematically.

To systematically evaluate the effect of resolution parameters in shotgun proteomic experiments, we used the Escherichia coli (E. coli) proteome as a model system with different MS and MS/MS resolution combinations. E. coli tryptic digests were fractionated by strong cation exchange chromatography and analyzed on an LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer coupled to a nanoflow reversed phase liquid chromatography system. The spectra were acquired in the Orbitrap mass analyzer at five different resolution settings for MS and in the LTQ or Orbitrap mass analyzer for MS/MS. We performed 100 LC-MS/MS runs using different combinations of resolution settings (each ‘setting’ being a specific resolution for MS in combination with a specific resolution for MS/MS) in the DDA mode. Using over 700,000 spectra generated in this study, false discovery rates (FDR) were calculated using target/decoy searches and 1% FDR was used as a cutoff value for comparison. The criteria for evaluating resolution parameters included a comparison of the number of total spectra and the total number of identified unique peptides, peptide-spectrum matches (PSMs) and unique proteins. Finally, five different FT-IT resolution settings were explored in greater detail to evaluate the resolution settings for an optimal LC-MS/MS analysis using a 48 standard protein mixture.

MATERALS AND METHODS

Sample preparation and processing

Escherichia coli MG1655 (E. coli) cultures were grown overnight at 37°C in LB medium (MP Biomedicals). The cells were washed three times in sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at room temperature and transferred to Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Invitrogen, Cat No. 31053-028) containing 0.584 g/L of glutamine and 0.11 g/L of sodium pyruvate and further cultured for 4 hrs. The cells were centrifuged, washed once with PBS and the pellet was lysed by sonicating in the presence of 0.5% SDS. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 20,000 g for 15 min and the supernatant was used for proteomic analysis. Protein concentration was determined using Lowry’s method. Protein reduction was carried out using 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) at 60°C for 20 min and subsequently alkylated with 10 mM iodoacetamide (IAA) in the dark at room temperature for 10 min. In-solution digestion was carried out using trypsin protease (Promega, 1:50 ratio in 0.01% SDS final) overnight at 37°C. [11] The tryptic digests were acidified by addition of formic acid (0.1% final concentration). The peptides were fractionated on a strong cation exchange (SCX) column (2.1 mm × 200 mm, 200 Å pore, PolySULFOETHYL A, PolyLC Inc., Columbia, MD) with a mobile phase of 25% acetonitrile, 10 mM KH2PO4 pH 2.85 (buffer A) and six fractions were generated by increasing the salt gradient up to 350 mM KCl in buffer A [21]. A 48 standard protein mixture (UPS1, Sigma-Aldrich) was digested using trypsin as described earlier [11].

LC-MS/MS experiments

Each SCX fraction was analyzed on an LTQ-Orbitrap XL ETD mass spectrometer (Thermo, San Jose, CA) at several resolution combinations. Approximately 1 μg of peptides were trapped on a 2 cm long trap column packed with C18 material (5 μm and 300 Å pore, Jupiter, Phenomenex) with 5 μL/min of flow rate at 99% solvent A (0.1% formic acid in H2O) and separated in 10 cm analytical column packed with C18 materials (5 μm and 300 Å pore, Jupiter, Phenomenex) by gradient from 10% solvent B (0.1% formic acid in 90% acetonitrile) to 60% solvent B for 65 min, to 97% solvent B for 74 min and to 90 min at 3% solvent B. All the MS spectra were acquired on the Orbitrap while the data dependent MS/MS spectra were acquired on either the LTQ or the Orbitrap. Four most intense precursor ions from a survey scan within m/z range from 400 to 1,400 above 20,000 of intensity were isolated with a 4 Da window and fragmented by CID with 35% normalized collision energy and the fragment ions were acquired at the profile mode with 1 microscan. The precursors were excluded, after fragmentation, for 90 seconds with a 0.02 Da window. Maximum ion injection times were set to 10 ms for MS and 100 ms for MS/MS. The automatic gain control targets were set to 5×10−5 for MS in the Orbitrap, 1×10−4 for MSn in the LTQ and 2×10−5 for MSn in the Orbitrap. For further FT-IT comparison, peptides from a 48 protein mix digest were separated on a homemade Magic AQ C18 column (10 cm × 75 μm, 5 μm and 100 Å pore, Michrom Bioresources, Inc) including a 2 cm Magic AQ C18 trap column. LC-MS/MS data was acquired in a data dependent mode in which 4 most intense precursor ions were isolated (width m/z= 4) for CID with 35% normalized collision energy and detected in LTQ. The automatic gain control targets were set to 1×10−6 for MS in the Orbitrap and 1×10−4 for MSn in the LTQ.

Data analysis

Statistics of acquired spectra

The total number of MS and MS/MS scans was directly counted from the raw data by summing the number of scans from five SCX fractions. There were 208,863 and 240,387 spectra acquired in FT for MS and MS/MS, respectively, and 115,356 and 149,078 spectra acquired in FT for MS and in IT for MS/MS, respectively, resulting in a total of 713,684 spectra. In a separate FT-IT experiment, fifteen LC-MS/MS analyses using standard proteins yielded a total of 168,873 spectra including 65,241 MS spectra in FT and 103,632 MS/MS spectra in IT.

Database search and processing

Tandem mass spectra were extracted from raw files using Mascot Daemon (version 2.2.2) with mass range from 600 Da to 5,000 Da. The processed spectral data were then searched against E. coli protein database (4,526 sequences and 1,431,860 residues) using Mascot search algorithms (version 2.2.0). The data from 48 protein mix was searched against IPI human protein database (148,380 sequences and 62,526,836 residues). In each case a reversed database was used to determine the false discovery rates (FDR). The search criteria included trypsin as protease with a maximum of 2 missed cleavages allowed. Carbamidomethylation at cysteine was set as a fixed modification, while deamidation at aspargine and glutamine and oxidation at methionine were set as variable modifications. Mass tolerance of ±30 ppm for precursor ions and 0.5 Da and 0.05 Da for fragments detected using Orbitrap and LTQ, respectively, were used in database search. The search results were downloaded from the Mascot server and processed using in-house python scripts for the estimation of FDR and the extracted data were stored in a MySQL database for subsequent analyses. As described previously, false discovery rates were calculated by dividing the number of PSMs from forward database search by the number of PSMs from reverse database search above a given score [22, 23].

Scan cycle times

For calculating the time acquired for one scan cycle (i.e. the time taken to acquire one MS scan and four subsequent MS/MS scans), we first counted the number of scans acquired in a 10 min window in the middle of the LC-MS/MS experiment where resolution setting for both MS and MS/MS were same. Hence average scan time is calculated by dividing 600 second by number of scans. Finally, the scan cycle time for each resolution combination was calculated based on the single scan times at the corresponding resolution.

Data availability

These raw data associated with this manuscript have been submitted to Tranche and are downloadable from the ProteomeCommons.org website (https://proteomecommons.org/tranche/) using the following hash: ROWCCrxC7ic21GeOrFnT/vKd/A/NwYLPjmfSu5iWIdIGMgciGNqEsHcGrU0XLTVjEvdPlW zOJlzq1CEwKOVwQbEgyMcAAAAAAABjHQ== The processed data along with the search results have also been submitted to the NCBI peptide data resource, Peptidome [24] and can be accessed using the URL http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/peptidome/repository/PSE126/.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Selection of resolution combinations for MS and MS/MS

LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer allows detection of gaseous ions and their fragments either in the linear ion trap (IT) or the Orbitrap (FT), where FT allows five different resolutions of 7,500 to 100,000 in both MS and MS/MS. We decided to test twenty different combinations of resolution parameters during data dependent acquisition such that the MS/MS resolution does not exceed that of MS. Indeed, in the context of a shotgun proteomic experiment, high resolution MS/MS spectra are of little use if the MS spectra themselves are acquired at low resolution. As shown in Figure 1, 15 combinations from FT for MS and FT for MS/MS were chosen from the maximum of 25 theoretical combinations such that the resolution at the MS/MS level was always the same or lower than the setting for MS. In addition, 5 combinations of FT for MS and IT for MS/MS were also used to compare the influence of the resolution. For example, the resolution of 100,000 for MS can be combined with the resolutions of 100,000, 60,000, 30,000, 15,000 and 7,500 for MS/MS, which will referred to as 100-100, 100-60, 100-30, 100-15 and 100-7, respectively, in this article. Each combination of parameters was used to run five SCX fractions as a set, thereby resulting in a total of 100 LC-MS/MS runs for comparison purposes. The data was searched against an E. coli database using the Mascot search algorithm.

Figure 1. Resolution combinations chosen for this study.

There are 36 possible resolution combinations in MS and MS/MS in an LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer. Of these 36 possible combinations, twenty were selected for comparison purposes in this study. For example, 60-15 indicates that the resolution of 60,000 for MS and 15,000 for MS/MS was employed to acquire data-dependent MS/MS spectra.

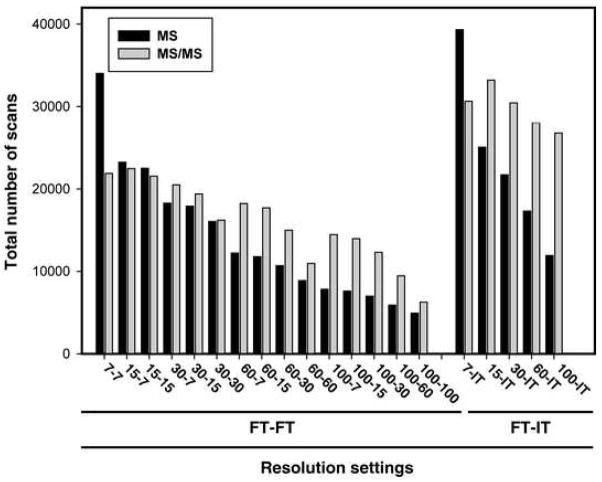

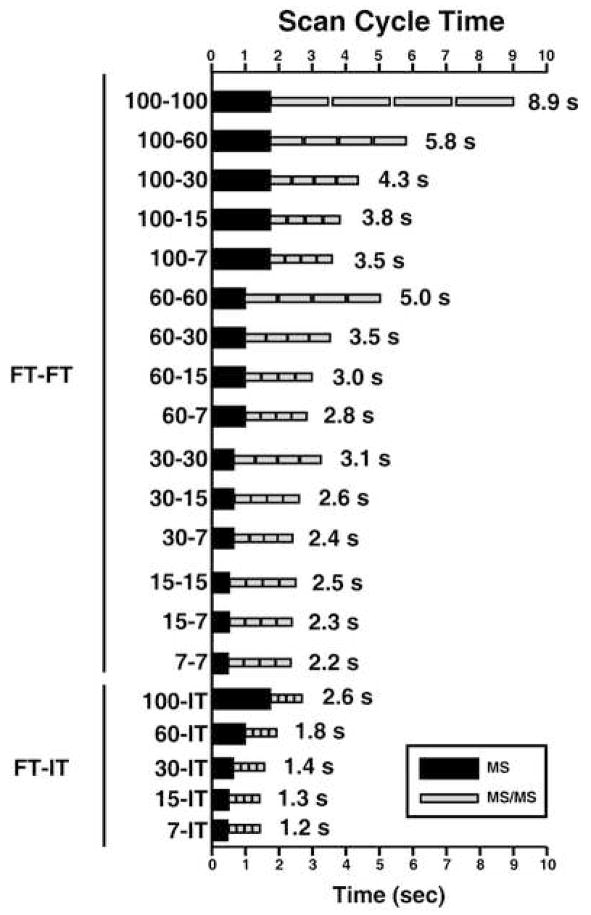

The number of MS/MS scans is inversely related to the scan cycle time

The number of scans differed considerably at various MS resolution parameters and with respect to detection methods (IT vs. FT) as shown in Figure 2. For example, the difference in the number of MS/MS spectra ranges from 1.2-fold between 100-IT (lowest in FT-IT experiments) and 15-7 (highest in FT-FT experiment) to 5-fold between 100-100 (lowest in FT-FT experiments) and 15-IT (highest in FT-IT experiments). The number of MS/MS spectra was similar in FT-IT experiments (~8.4% relative standard deviation (RSD)), while they varied greatly in FT-FT experiments (~30% RSD). As expected, the number of MS/MS scans acquired at lower MS/MS resolution either by FT or IT was greater than those acquired at higher resolution. This is because of the fact that increasing resolution increases scan duration. As described in data analysis section, acquiring scans at resolution of 7,500, 15,000, 30,000, 60,000 or 100,000 took, on average, 0.44, 0.50, 0.62, 1.00 and 1.78 seconds, respectively. Based on these estimates, scan cycle times at different resolution combinations (i.e., one scan cycle consisting of one MS scan followed by four MS/MS scans) was calculated. For example, one scan cycle took 8.9 seconds at 100-100, while only 1.2 seconds were used in one scan cycle at 7-IT. Thus the scan cycle times at 100-100 are ~7-fold, ~4-fold, ~3-fold and ~2-fold longer than those at 7-IT, 7-7, 60-15 and 100-30, respectively. The scan cycle times were similar at 7-7, 15-7, 15-15 and 30-7 and quite short (1.2~1.8s) for 7-IT, 15-IT, 30-IT and 60-IT as shown in Figure 3. As expected, it was observed that the scan cycle time was inversely proportional to the number of MS/MS scans.

Figure 2. Total number of MS and MS/MS scans.

Total number of MS and MS/MS scans was directly counted from each raw file. The number of MS scans varied greatly at different resolution combinations ranging from ~5,000 (100-100) to ~40,000 (7-IT) while those of MS/MS scans ranged from ~6,000 (100-100) to ~33,000 (15-IT).

Figure 3. Scan cycle times for FT-IT and FT-FT experiments.

The scan cycle times (i.e. one MS scan and the subsequent four MS/MS scans) were calculated based on actual scan times at resolutions of 7-7, 15-15, 30-30, 60-60 and 100-100 resulting in total scan cycle times of 0.44s, 0.50s, 0.62s, 1.00s and 1.78s, respectively. The slowest scan cycle time was observed at 100-100, while the fastest scan cycle times were observed at 7-IT, 15-IT, 30-IT and 60-IT.

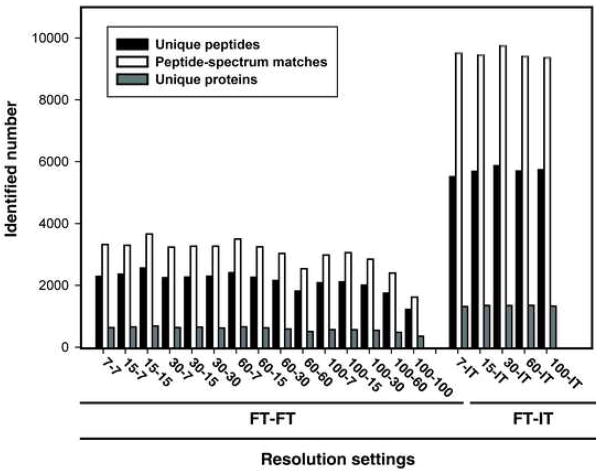

Resolution settings yielding the highest number of peptide-spectrum matches, unique peptides and proteins

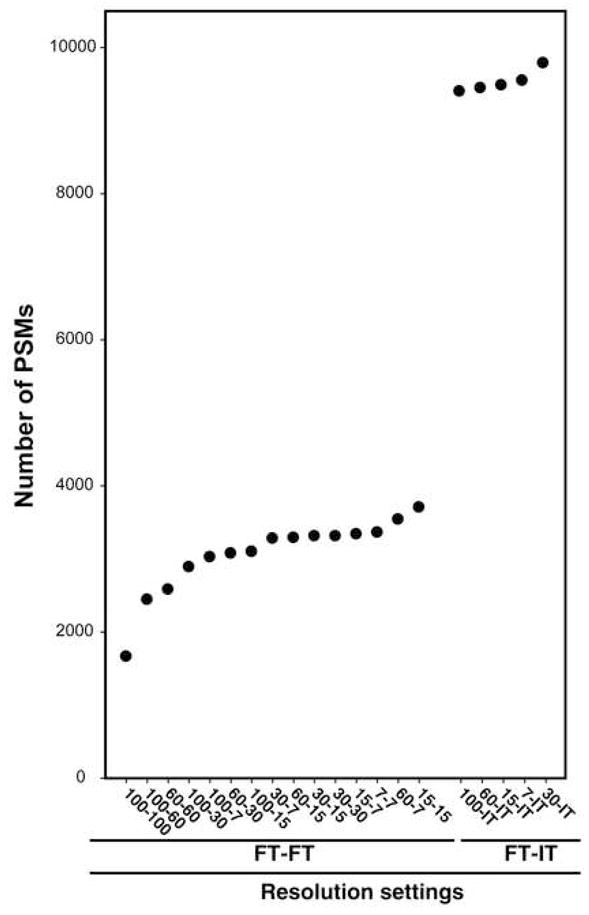

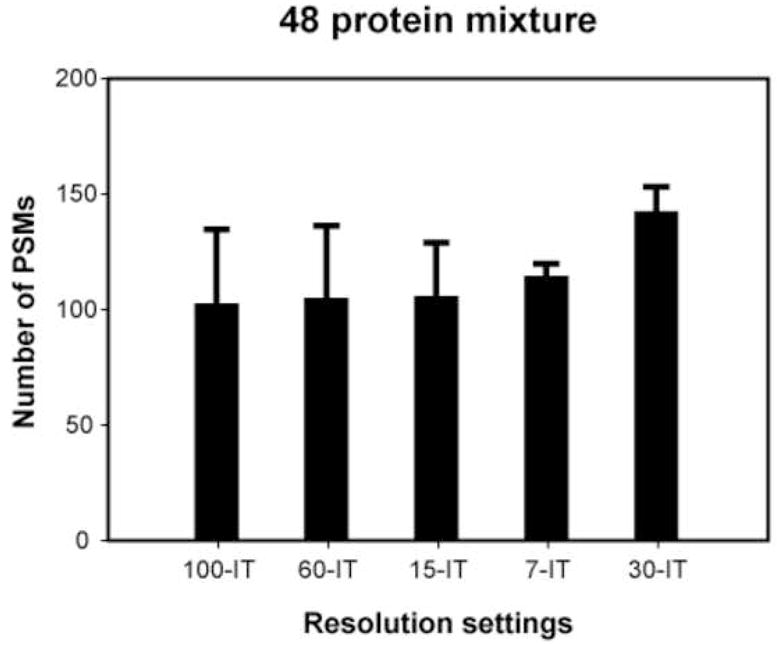

The total number of unique peptides, peptide-spectrum-matches (PSMs) or unique proteins identified at 1% FDR was examined at all resolution combinations (Figure 4). In FT-FT experiments, the number of unique peptides ranged from 1,264 at 100-100 to 2,603 at 15-15 and PSMs from 1,663 at 100-100 to 3,705 at 15-15. The number of unique proteins identified was 398 at 100-100 and 725 at 15-15. In FT-IT experiments, the number of unique peptides was 5,554 at 7-IT and 5,909 at 30-IT while the number of PSMs was 9,401 at 100-IT and 9,789 at 30-IT. The number of unique proteins ranged from 1,356 at 7-IT to 1,393 at 60-IT. The number of unique peptides, PSMs and unique proteins exhibited a greater variation in the FT-FT experiments, while a similar number of unique peptides, PSMs and unique proteins were identified across all the FT-IT experiments. To better assess whether the differences in the identification between FT-FT group and FT-IT group were statistically significant, we performed a two-tailed unpaired t-test. We observed that the number of PSMs in FT-FT group was significantly lower than that observed in FT-IT group (p-value = 1.8×10−16). This can be explained by the fact that IT detection is more sensitive that FT detection because of faster scan speed and lower detection threshold in the ion-trap [25]. Although the difference in the number of PSMs obtained at different FT-IT settings was not dramatic (9,401-9,789 PSMs), there was a large variation in the number of PSMs at different FT-FT settings (1,663-3,705 PSMs) with the maximum number of PSMs observed at the 15-15 setting (Figure 5). Although, additional experiments will be required to evaluate this in greater detail, it seems that longer scan cycle times (e.g. 100-100, 100-60 and 60-60) result in a corresponding decrease in PSMs. Within the FT-IT group, we wished to determine if any resolution combination consistently led to a higher number of PSMs. Thus, we analyzed a 48 protein mix in triplicate at the five different FT-IT settings. We again observed that the maximum number of PSMs was obtained at an MS resolution of 30,000. This number was significantly higher (p-value < 0.05) than all other resolution settings except for 60-IT (Figure 6).

Figure 4. Distribution of the number of unique peptides, peptide-spectrum matches and unique proteins.

The number of unique peptides, peptide-spectrum-matches (PSMs) and unique proteins is shown at the indicated resolution combinations at 1% FDR.

Figure 5. Ordered resolution combinations by the number of peptide-spectrum matches.

The number of PSMs identified at 1% FDR was used to order resolution combinations.

Figure 6. Comparison of different resolution settings in FT-IT experiments.

The number of PSMs at different resolution settings at 1% FDR using the 48 protein standard mixture are shown. Error bars denote standard deviations of the number of PSMs obtained in each case.

CONCLUSIONS

The impact of resolution parameters on the throughput of tandem mass spectrometry experiments was systematically assessed in this study. In our analysis, based on the number of unique peptides, PSMs and unique proteins identified at 1% FDR from E coli proteome, a higher number of identifications were obtained in the FT-IT experiments as compared to FT-FT experiments. For maximizing the number of identifications, we found that 30-IT settings (closely followed by 60-IT setting) performed significantly better than other settings from a 48 protein mixture. Thus, we conclude that the rate of identification could be maximized at 30-IT setting for proteomic profiling studies. However, 15-15 setting may be preferable for applications such as high throughput post-translational modification analysis, proteogenomic studies and de novo sequencing; where one seeks a compromise between the number of identifications and a high accuracy of identification.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a grant S10RR023025 from the High End Instrumentation Program of the National Institutes of Health, a Department of Defense Era of Hope Scholar award (W81XWH-06-1-0428), an NIH roadmap grant for Technology Centers of Networks and Pathways (U54RR020839) and a contract N01-HV-28180 from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Makarov A. Electrostatic axially harmonic orbital trapping: a high-performance technique of mass analysis. Anal Chem. 2000;72(6):1156–62. doi: 10.1021/ac991131p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yates JR, Ruse CI, Nakorchevsky A. Proteomics by mass spectrometry: approaches, advances, and applications. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2009;11:49–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-061008-124934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Makarov A, Denisov E, Kholomeev A, Balschun W, Lange O, Strupat K, Horning S. Performance evaluation of a hybrid linear ion trap/orbitrap mass spectrometer. Anal Chem. 2006;78(7):2113–20. doi: 10.1021/ac0518811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clauser K, Baker P, Burlingame A. Role of accurate mass measurement (+/- 10 ppm) in protein identification strategies employing MS or MS MS and database searching. Anal Chem. 1999;71(14):2871–2882. doi: 10.1021/ac9810516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zubarev R, Hakansson P, Sundqvist B. Accuracy requirements for peptide characterization by monoisotopic molecular mass measurements. Anal Chem. 1996;68(22):4060–4063. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conrads TP, Anderson GA, Veenstra TD, Pasa-Tolic L, Smith RD. Utility of accurate mass tags for proteome-wide protein identification. Anal Chem. 2000;72(14):3349–54. doi: 10.1021/ac0002386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Syka JE, Coon JJ, Schroeder MJ, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF. Peptide and protein sequence analysis by electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(26):9528–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffin TJ, Xie H, Bandhakavi S, Popko J, Mohan A, Carlis JV, Higgins L. iTRAQ reagent-based quantitative proteomic analysis on a linear ion trap mass spectrometer. J Proteome Res. 2007;6(11):4200–9. doi: 10.1021/pr070291b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsen JV, Macek B, Lange O, Makarov A, Horning S, Mann M. Higher-energy C-trap dissociation for peptide modification analysis. Nat Methods. 2007;4(9):709–12. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bushey JM, Baba T, Glish GL. Simultaneous Collision Induced Dissociation of the Charge Reduced Parent Ion during Electron Capture Dissociation. Anal Chem. 2009;81(15):6156–6164. doi: 10.1021/ac900627n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molina H, Matthiesen R, Kandasamy K, Pandey A. Comprehensive comparison of collision induced dissociation and electron transfer dissociation. Anal Chem. 2008;80(13):4825–35. doi: 10.1021/ac8007785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo T, Gan CS, Zhang H, Zhu Y, Kon OL, Sze SK. Hybridization of pulsed-Q dissociation and collision-activated dissociation in linear ion trap mass spectrometer for iTRAQ quantitation. J Proteome Res. 2008;7(11):4831–40. doi: 10.1021/pr800403z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kocher T, Pichler P, Schutzbier M, Stingl C, Kaul A, Hasenfuss G, Teucher N, Penninger J, Mechtler K. High precision quantitative proteomics using iTRAQ on an LTQ Orbitrap: a new mass spectrometric method combining the benefits of all. J Proteome Res. 2009 doi: 10.1021/pr900451u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wenner BR, Lynn BC. Factors that affect ion trap data-dependent MS/MS in proteomics. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2004;15(2):150–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perkins DN, Pappin DJ, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS. Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis. 1999;20(18):3551–67. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3551::AID-ELPS3551>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eng J, McCormack A, Yates J. An approach to correlate tandem mass-spectral data of peptides with amino-acid-sequences in a protein database. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1994;5(11):976–989. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geer LY, Markey SP, Kowalak JA, Wagner L, Xu M, Maynard DM, Yang X, Shi W, Bryant SH. Open mass spectrometry search algorithm. J Proteome Res. 2004;3(5):958–64. doi: 10.1021/pr0499491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Craig R, Beavis RC. TANDEM: matching proteins with tandem mass spectra. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(9):1466–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong CC, Cociorva D, Venable JD, Xu T, Yates JR. 3rd, Comparison of different signal thresholds on data dependent sampling in Orbitrap and LTQ mass spectrometry for the identification of peptides and proteins in complex mixtures. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2009;20(8):1405–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y, Wen Z, Washburn MP, Florens L. Effect of Dynamic Exclusion Duration on Spectral Count Based Quantitative Proteomics. Anal Chem. 2009;81(15):6317–6326. doi: 10.1021/ac9004887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaerkady R, Harsha HC, Nalli A, Gucek M, Vivekanandan P, Akhtar J, Cole RN, Simmers J, Schulick RD, Singh S, Torbenson M, Pandey A, Thuluvath PJ. A quantitative proteomic approach for identification of potential biomarkers in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Proteome Res. 2008;7(10):4289–98. doi: 10.1021/pr800197z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elias JE, Gygi SP. Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat Methods. 2007;4(3):207–14. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kandasamy K, Pandey A, Molina H. Evaluation of Several MS/MS Search Algorithms for Analysis of Spectra Derived from Electron Transfer Dissociation Experiments. Anal Chem. 2009;81(17):7170–7180. doi: 10.1021/ac9006107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slotta DJ, Barrett T, Edgar R. NCBI Peptidome: a new public repository for mass spectrometry peptide identifications. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27(7):600-1. doi: 10.1038/nbt0709-600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olsen JV, Schwartz JC, Griep-Raming J, Nielsen ML, Damoc E, Denisov E, Lange O, Remes P, Taylor D, Splendore M, Wouters ER, Senko M, Makarov A, Mann M, Horning S. A Dual Pressure Linear Ion Trap Orbitrap Instrument with Very High Sequencing Speed. Molecular and Cellular Proteomics. 2009;8:2759. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900375-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

These raw data associated with this manuscript have been submitted to Tranche and are downloadable from the ProteomeCommons.org website (https://proteomecommons.org/tranche/) using the following hash: ROWCCrxC7ic21GeOrFnT/vKd/A/NwYLPjmfSu5iWIdIGMgciGNqEsHcGrU0XLTVjEvdPlW zOJlzq1CEwKOVwQbEgyMcAAAAAAABjHQ== The processed data along with the search results have also been submitted to the NCBI peptide data resource, Peptidome [24] and can be accessed using the URL http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/peptidome/repository/PSE126/.