Abstract

We evaluated the effects of previous pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) on the risk of obstructive lung disease. We analyzed population-based, the Second Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001. Participants underwent chest X-rays (CXR) and spirometry, and qualified radiologists interpreted the presence of TB lesion independently. A total of 3,687 underwent acceptable spirometry and CXR. Two hundreds and ninty four subjects had evidence of previous TB on CXR with no subjects having evidence of active disease. Evidence of previous TB on CXR were independently associated with airflow obstruction (adjusted odds ratios [OR] = 2.56 [95% CI 1.84-3.56]) after adjustment for sex, age and smoking history. Previous TB was still a risk factor (adjusted OR = 3.13 [95% CI 1.86-5.29]) with exclusion of ever smokers or subjects with advanced lesion on CXR. Among never-smokers, the proportion of subjects with previous TB on CXR increased as obstructive lung disease became more severe. Previous TB is an independent risk factor for obstructive lung disease, even if the lesion is minimal and TB can be an important cause of obstructive lung disease in never-smokers. Effort on prevention and control of TB is crucial in reduction of obstructive lung disease, especially in countries with more than intermediate burden of TB.

Keywords: Tuberculosis; Lung Diseases, Obstructive

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are major public health problems worldwide. Despite intensive global efforts, the total number of new TB cases is still increasing, with 9.27 million new cases and 1.78 million deaths in 2006 (1). The mortality rate of COPD is also increasing, and more than three million people worldwide were estimated to die from COPD in 2005 (2). About 80 million people worldwide are estimated to have moderate-to-severe COPD. Several previous reports have suggested an association between these two diseases. There is a high and increasing prevalence of obstructive lung disease in patients who are being treated for pulmonary TB (3). A previous epidemiological study found that the prevalence of COPD may be different in subjects with and those without a history of TB (4). Another population-based study found that a history of TB is closely associated with airflow obstruction (5).

Although some previous studies have shown an association of TB and obstructive lung disease, most of these studies had small sample sizes and did not totally exclude the effect of smoking, a potential and strong confounding factor. Smoking is a major cause of COPD (6) and also increases the risk of developing TB (7). In most studies, a medical history of TB is based on self-reporting, a method limited by recall bias. Patients with spontaneously healed TB will not report a history of TB, and that can be the cause of underestimation on the presence of TB (8). Therefore, a previous TB should be also evaluated by chest imaging.

In the present study, we evaluated the risk attributable to pulmonary TB on the development of obstructive lung disease. We performed nationwide representative sampling in Korea, a country with an intermediate TB burden. We also evaluated the risk in patients with minimal TB lesions, and in patients who have never smoked.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data collection

We analyzed the Second Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES II) 2001 data that were prospectively collected in 2001 by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. Based on the 2000 Population Census of the National Statistical Office of Korea, a stratified, multi-stage, clustered, probability design was used to select a representative sample of civilian, non-institutionalized Korean adults aged 18 yr and older. Trained interviewers visited subjects' homes and administered standardized questionnaires to determine health status.

Pulmonary function test

Spirometry was conducted by trained pulmonary technicians according to the 1994 American Thoracic Society (ATS) recommendations (9), using Dry Rolling-seal spirometry (Vmax-2130, Sensor-Medics, Yorba Linda, CA, USA). The electronically generated spirometric data were transferred via the internet to the review center on the same day. Two trained nurses reviewed the test results and provided quality control feedback to the technicians. All data were saved for further analysis. Even though the ATS recommendations require three or more acceptable curves for an adequate test, this is not practical for a large-scale examination survey, so we analyzed only the data of subjects with two or more acceptable spirometry performances (10). The predicted forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) were derived from the survey data of lifetime nonsmoking subjects with normal chest radiographs and no history of respiratory disease or symptoms (11). Airflow obstruction was defined as FEV1/FVC less than 70% (6) or lower limit of normal (LLN) (12).

Chest radiograph (CXR)

CXR images were taken in specially-equipped mobile examination cars at the time of spirometry. Two qualified radiologists evaluated CXRs independently using standard criteria for reporting of radiological abnormalities (13). If there was disagreement about interpretation of a CXR, the two radiologists discussed this with a third radiologist and reached a consensus. TB lesion on CXR was defined as the presence of discrete linear or reticular fibrotic scars, or dense nodules with distinct margins, with or without calcification, within the upper lobes. Based on CXR findings, we categorized the TB lesion of each subject as minimal, moderately advanced, or far-advanced, based on the classification of the National Tuberculosis and Respiratory Disease Association of the USA (14).

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between variables were tested using the chi-square test or Student's t-test. We constructed a logistic regression model with obstructive lung disease as the dependent variable and age, sex, smoking history (more than 2 weeks), and TB lesions on CXR as independent variables. A forward selection method was used to exclude multi-colinearity of each variable. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated with PASW 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethics statement

The institutional review board of the Asan Medical Center (Seoul, Korea) approved this analysis of the Korean population, which was prospectively collected. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects during the initial data collection.

RESULTS

Characteristics of enrolled subjects

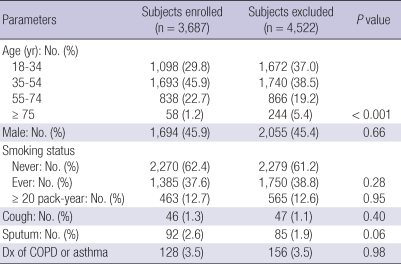

Among 9,243 subjects (> 18 yr old), 8,209 (88.8%) responded to the questionnaires, 4,479 (48.5%) completed spirometry and CXR; and 3,687 (39.9%) subjects underwent at least two spirometry measurements acceptable by ATS criteria with chest radiograph data (we analyzed these subjects). Although there was significant difference in age distribution between subjects enrolled and excluded, the pattern of sex, smoking status, respiratory symptoms, physician based diagnosis of COPD and asthma, and mean age (43.4 yr in enrolled vs 43.1 yr in excluded, P = 0.33) were similar, suggesting the data were representative (Table 1). Among 3,687 enrolled for analysis, radiologists concluded that 294 (8.0%) subjects were classified as having TB lesion on CXR. All TB lesions were classified as inactive and there was no subject with lesion indicative of active TB on CXR. Two hundreds and ninty subjects had minimal lesions and four subjects had moderately or far-advanced lesions. Initial interpretation between two radiologists about the presence of TB lesion showed almost perfect agreement (κ = 0.95, P < 0.001) with 99.3% of agreement rate. There were characteristic differences in sex, age and number of smokers between subjects with and without TB lesion on CXR. Group with TB lesion on CXR had higher mean age (53.3 ± 14.0 yr vs 42.5 ± 14.0 yr, P < 0.001), more male sex (184/294 [62.6%] vs 1,510/3,393 [44.5%], P < 0.001) and more smokers (156/294 [53.1%] vs 1,229/3,393 [36.2%], P < 0.001).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the subjects

Dx, physician diagnosis; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

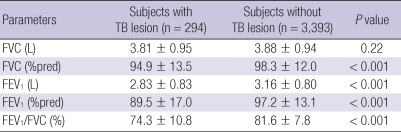

Pulmonary function as the presence of TB lesion on CXR

Subjects with TB lesion had relatively lower FVC per predicted value (94.9 ± 13.5% vs 98.3 ± 12.0%, P < 0.001), FEV1 (2.83 ± 0.83L vs 3.16 ± 0.80, P < 0.001), FEV1 per predicted value (89.5 ± 17.0% vs 97.2 ± 13.1, P < 0.001) and FEV1/FVC (74.3 ± 10.8% vs 81.6 ± 7.8, P < 0.001), compared with those without TB lesion on CXR. FVC did not show significant difference between two groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pulmonary function of subjects with or without TB lesion on CXR

CXR, chest X-rays; TB, tuberculosis; %pred, % of predicted value; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second.

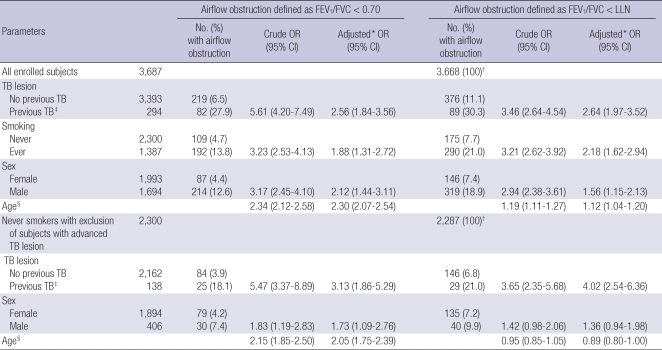

The risk of airflow obstruction by TB lesions on CXR

Based on univariate analysis, male sex, age, smoking history, and TB lesions were associated with airflow obstruction. After adjustment for sex, age, smoking history, TB lesions on CXR were still associated with airflow obstruction. Adjusted ORs were 2.56 (95% CI = 1.84-3.56) by the definition of airflow obstruction FEV1/FVC < 0.70 and 2.64 (95% CI = 1.97-3.52) by FEV1/FVC < LLN. After excluding subjects with smoking histories and subjects with moderate or far-advanced TB lesions (n = 2,298), minimal TB lesions on CXR remained associated with airflow obstruction, with adjusted ORs of 3.13 (95% CI = 1.86-5.29) by the definition of airflow obstruction FEV1/FVC < 0.70 and 4.02 (95% CI = 2.54-6.36) by FEV1/FVC < LLN (Table 3).

Table 3.

Risks of airflow obstruction by previous TB. Odd Ratios are analyzed in all enrolled subjects and in never smokers with exclusion of subjects with advanced TB lesion, separately

*Adjusted for TB lesion on CXR, smoking history, sex and age; †Subjects without data of height and weight were excluded in analysis; ‡Previous TB was defined by TB lesions on chest X-ray; §Odds ratio as age increased by 10 yr. TB, tuberculosis; LLN, lower limit of normal; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

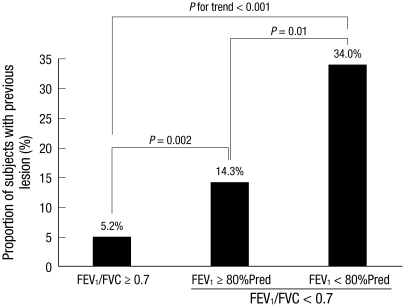

Subjects with TB lesions as severity of airflow obstruction among never smokers

Among never smokers, the proportion of subjects with TB lesions increased as the severity of obstructive lung disease increased (P for trend < 0.001). A total of 113 (5.2%) of 2,190 subjects without airflow obstruction (FEV1/FVC > 0.7) had TB lesions. Among subjects with airflow obstruction, 9 (14.3%) of 63 subjects with FEV1 ≥ 80% of predicted values, 16 (34.0%) of 47 with FEV1 < 80% of predicted values had TB lesions (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Proportion of subjects with TB lesion as the severity of airflow obstruction. % Pred, % of predicted value; TB, tuberculosis; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second.

DISCUSSION

In this study, based on a nationwide representative sampling of Korean subjects, we found that previous TB was a risk factor for obstructive lung disease and even a minimal TB lesion was an also strong risk factor in never smokers. The proportions of subjects with previous TB lesion increased as the severity of obstructive lung disease, suggesting previous TB is an important contributing factor for obstructive lung disease among never smokers.

Previous studies have suggested that pulmonary TB is associated with obstructive lung disease. Patients with previous pulmonary TB were more likely to suffer from acute exacerbation of COPD than those who did not have pulmonary TB (15). In silicosis patients, history of TB is an independent predictor of airflow obstruction (16). The bronchodilator response of patients with a tuberculous-destroyed lung is lower than that of patients with COPD (17). Airflow impairment is related to the radiological extent of TB (3) and to the number of TB episodes. However, most of these studies had small sample sizes, were not population-based, or did not fully adjust for smoking history. A smoking history could potentially have biased the estimated effect of TB on loss of lung function. A previous study found that smoking history is associated with an increased risk of TB for a cohort of white gold miners, and smoking is known to increase lung function loss (18). Recently, a population-based study of Latin American middle-aged and older adults found that previous medical diagnosis of TB was associated with airflow obstruction (5). A cohort study showed that radiologic evidence of inactive TB was associated with increased risk of airflow obstruction, although it was not population-based (8).

A history of TB may affect lung function by pleural change, bronchial stenosis, or parenchymal scarring. TB increases the activity of the matrix metalloproteinases, thus contributing to pulmonary damage (19). Extensive TB lesions may produce restrictive changes, with reduced transfer of carbon monoxide in the lung (20). However, we found that the presence of minimal lesions was also an independent risk factor for airflow obstruction. In these patients, airway fibrosis and inflammation may play important roles. TB infection is associated with airway fibrosis and the immune response to mycobacteria could cause airway inflammation, a characteristic of obstructive lung disease (21).

Smoking is a well-established major risk factor for COPD (22) and much COPD research has focused on smokers (23). However, recent evidence suggests that other risk factors are also important in causing obstructive lung disease, especially in developing countries. These factors include air pollutants, dust and fumes, history of repeated lower respiratory tract infections during childhood, chronic asthma, intrauterine growth retardation, poor nourishment, and poor socioeconomic status. Several questionnaire studies have also suggested that a history of TB is a risk factor for airflow obstruction (24, 25). In our study, 22.7% (25/110) of never smokers with airflow obstruction had TB lesions, and the proportion increased for subjects with FEV1 < 80% of predicted value. This suggests that previous TB can be an important cause of obstructive lung disease among never smokers.

In this study, we defined airflow obstruction as FEV1/FVC less than 0.70 or LLN. Although a fixed ratio of 0.70 is simple and widely used, it is criticized due to over-diagnosis of both the presence and severity of COPD in the elderly (26). TB lesion on CXR was still associated with airflow obstruction (adjusted OR = 2.66, 95% CI 1.99-3.55, P < 0.001) and it is consistent in never smokers (adjusted OR = 4.02, 95% CI 2.54-6.36, P < 0.001), when we defined obstructive lung disease by LLN. We enrolled subjects with two or more acceptable spirometry performances for practical consideration of a large-scale examination survey. ATS and European Respiratory Society (ERS) recommendations was published after this survey, requiring three or more acceptable curves for an adequate test with the differance in the two largest values of FVC or FEV1 < 0.150 L (27). When we adopted this recommendation (n = 2,533), TB lesion on CXR was still associated with airflow obstruction (FEV1/FVC < 0.70) with adjusted OR = 2.20, 95% CI 1.44-3.35, P < 0.001) and it was also consistent in never smokers (adjusted OR = 3.38, 95% CI 1.75-6.55, P = 0.001).

This study has some limitations. First, airflow obstruction was defined by FEV1/FVC rather than post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC. This might lead to an overestimate of the prevalence of obstructive lung disease. However, our estimates are similar to those of previous studies. Second, previous TB was only evaluated by CXR and clinical history was not examined. From a specificity point of view, a lesion that seems to be TB-related on CXR could be a sequela of other diseases such as pneumonia. From a view of sensitivity, CXR could miss some parenchymal TB lesions, which can only be identified by computed tomography (CT) analysis (28, 29). In addition, some TB patients might have had complete healing without any evidence on the CXR. Although CXR has limitations in confirming previous TB, in the present study 3 qualified radiologists interpreted the CXRs to reduce this limitation and interpretation on CXRs of radiologists showed almost perfect agreement. Third, there was relatively large number of subjects with TB lesion on CXR (8.0%), compared with the number of TB reports in Korea (30). In other study, the prevalence of prior TB based on self-reports (2.9%) was also significantly lower than that defined by CXR (24.2%) (8). Considering this discrepancy between radiologic evidence and self-report of TB and continuously decreasing annual incidence in Korea, our interpretations of TB lesion on CXR do not seem to go beyond reasonable level. Fourth, there were only four subjects with advanced TB lesion. In this survey, subjects should visit a car with special equipment to undergo spirometry. Therefore, the possibility of selection bias, to enroll relatively healthy subjects mainly, cannot be excluded.

In conclusion, previous TB was an independent risk factor for obstructive lung disease, even if the lesions are minimal. TB could be also an important cause of airflow obstruction in subjects who had never smoked. The results of this population-based study indicated that appropriate management and control of TB is as important as smoking quitting for reducing obstructive lung disease.

AUTHOR SUMMARY

The Risk of Obstructive Lung Disease by Previous Pulmonary Tuberculosis in a Country with Intermediate Burden of Tuberculosis

Sei Won Lee, Young Sam Kim, Dong-Soon Kim, Yeon-Mok Oh, and Sang-Do Lee

We evaluated the effects of previous pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) on the risk of obstructive lung disease. We analyzed population-based, the Second Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001. Participants underwent chest X-rays (CXR) and spirometry, and qualified radiologists interpreted the presence of TB lesion independently. Among 3,687 participants, 294 subjects had evidence of previous TB on CXR. Evidence of previous TB on CXR were independently associated with airflow obstruction (odds ratios = 2.56, 95% CI 1.84-3.56) after adjustment for sex, age and smoking history. Previous TB was still a risk factor with exclusion of ever smokers or subjects with advanced lesion on CXR. Previous TB is an independent risk factor for obstructive lung disease, even if the lesion is minimal and TB can be an important cause of obstructive lung disease in never smokers.

References

- 1.Global tuberculosis control: surveillance, planning, financing. WHO report 2007. Report No.: (WHO/HTM/TB/ 2007.376) World Health Organization. [accessed on 11 Feb 2010]. Available at http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/2007/pdf/full.pdf.

- 2.Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Burden, 2008. World Health Organization. [accessed on 17 Sep 2009]. Available at http://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/burden/en/index.html.

- 3.Willcox PA, Ferguson AD. Chronic obstructive airways disease following treated pulmonary tuberculosis. Respir Med. 1989;83:195–198. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(89)80031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim SJ, Suk MH, Choi HM, Kimm KC, Jung KH, Lee SY, Lee SY, Kim JH, Shin C, Shim JJ, In KH, Kang KH, Yoo SH. The local prevalence of COPD by post-bronchodilator GOLD criteria in Korea. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:1393–1398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menezes AM, Hallal PC, Perez-Padilla R, Jardim JR, Muino A, Lopez MV, Valdivia G, Montes de Oca M, Talamo C, Pertuze J, Victora CG. Latin American Project for the Investigation of Obstructive Lung Disease (PLATINO) Team. Tuberculosis and airflow obstruction: evidence from the PLATINO study in Latin America. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:1180–1185. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00083507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Global Institute for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Geneva, Switzerland: 2008. [accessed on 17 Sep 2009]. Workshop report: global strategy for diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD. Available at http://www.goldcopd.org. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lowe CR. An association between smoking and respiratory tuberculosis. Br Med J. 1956;2:1081–1086. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5001.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lam KB, Jiang CQ, Jordan RE, Miller MR, Zhang WS, Cheng KK, Lam TH, Adab P. Prior tuberculosis, smoking and airflow obstruction: a cross-sectional analysis of the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study. Chest. 2010;137:593–600. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Thoracic Society. Standardization of Spirometry, 1994 Update. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1107–1136. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim DS, Kim YS, Jung KS, Chang JH, Lim CM, Lee JH, Uh ST, Shim JJ, Lew WJ Korean Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Korea: a population-based spirometry survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:842–847. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200502-259OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi JK, Paek D, Lee JO. Normal predictive values of spirometry in Korean population. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2005;58:230–242. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hwang YI, Kim CH, Kang HR, Shin T, Park SM, Jang SH, Park YB, Kim CH, Kim DG, Lee MG, Hyun IG, Jung KS. Comparison of the prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease diagnosed by lower limit of normal and fixed ratio criteria. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24:621–626. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.4.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Instruction to panel for completing chest X-ray and classification worksheet (DS-3024) The United States of America Department of State. [accessed on 26 Nov 2009]. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dq/dsforms/3024.htm.

- 14.Falk AJ, O'Connor B, Pratt PC. Classification of pulmonary tuberculosis. 12th ed. New York: National Tuberculosis and Respiratory Disease Association; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohan A, Premanand R, Reddy LN, Rao MH, Sharma SK, Kamity R, Bollineni S. Clinical presentation and predictors of outcome in patients with severe acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring admission to intensive care unit. BMC Pulm Med. 2006;6:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leung CC, Chang KC, Law WS, Yew WW, Tam CM, Chan CK, Wong MY. Determinants of spirometric abnormalities among silicotic patients in Hong Kong. Occup Med (Lond) 2005;55:490–493. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqi107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JH, Chang JH. Lung function in patients with chronic airflow obstruction due to tuberculous destroyed lung. Respir Med. 2003;97:1237–1242. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(03)00255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hnizdo E, Murray J. Risk of pulmonary tuberculosis relative to silicosis and exposure to silica dust in South African gold miners. Occup Environ Med. 1998;55:496–502. doi: 10.1136/oem.55.7.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elkington PT, Friedland JS. Matrix metalloproteinases in destructive pulmonary pathology. Thorax. 2006;61:259–266. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.051979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hallett WY, Martin CJ. The diffuse obstructive pulmonary syndrome in a tuberculosis sanatorium. I. Etiologic factors. Ann Intern Med. 1961;54:1146–1155. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-54-6-1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salvi SS, Barnes PJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in non-smokers. Lancet. 2009;374:733–743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fletcher C, Peto R. The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction. Br Med J. 1977;1:1645–1648. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6077.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tzanakis N, Anagnostopoulou U, Filaditaki V, Christaki P, Siafakas N COPD group of the Hellenic Thoracic Society. Prevalence of COPD in Greece. Chest. 2004;125:892–900. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.3.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ehrlich RI, White N, Norman R, Laubscher R, Steyn K, Lombard C, Bradshaw D. Predictors of chronic bronchitis in South African adults. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8:369–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caballero A, Torres-Duque CA, Jaramillo C, Bolívar F, Sanabria F, Osorio P, Orduz C, Guevara DP, Maldonado D. Prevalence of COPD in five Colombian cities situated at low, medium, and high altitude (PREPOCOL study) Chest. 2008;133:343–349. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hardie JA, Buist AS, Vollmer WM, Ellingsen I, Bakke PS, Mørkve O. Risk of over-diagnosis of COPD in asymptomatic elderly never-smokers. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:1117–1122. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00023202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, Crapo R, Enright P, van der Grinten CP, Gustafsson P, Jensen R, Johnson DC, MacIntyre N, McKay R, Navajas D, Pedersen OF, Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Wanger J ATS/ERS Task Force. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee KS, Im JG. CT in adults with tuberculosis of the chest: characteristic findings and role in management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:1361–1367. doi: 10.2214/ajr.164.6.7754873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HJ, Lee HJ, Kwon SY, Yoon HI, Chung HS, Lee CT, Han SK, Shim YS, Yim JJ. The prevalence of pulmonary parenchymal tuberculosis in patients with tuberculous pleuritis. Chest. 2006;129:1253–1258. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.5.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Annual report on the notified tuberculosis patients in Korea. The Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [accessed on 30 Sep 2009]. Available at http://tbnet.cdc.go.kr/rv/TBC_Gnss_Sttst_LN.dm.