Abstract

Incontinentia pigmenti (IP) (OMIM #308300) is a rare X-linked dominant neuroectodermal multisystemic syndrome due to mutations in the gene for NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO). A term newborn girl who was born with erythematous vesicular eruptions developed recurrent seizures during the first and second weeks of her life. The serial MRIs demonstrated diffuse, progressive brain infarctions and subsequent encephalomalacia as well as brain atrophy. Skin biopsy found it was consistent with the vesicular stage of IP. Genetic analysis revealed a deletion exon 4-10 in NEMO gene associated with IP. We hereby report a Korean female baby with IP confirmed by mutation analysis of NEMO gene.

Keywords: Incontinentia Pigmenti; NEMO Protein; Brain Infarction; Seizures; Infant, Newborn

INTRODUCTION

Incontinentia pigmenti (IP) is a rare X-linked dominant inherited disorder due to a mutation in the NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO)/inhibitor kappa kinase (IKK)-gamma gene. It primarily affects the tissues and organs derived from ectoderm or neuroectoderm and represents a type of ectodermal dysplasia. The skin lesions, linear blisters in an otherwise well baby girl, are the most characteristic feature of IP, although the inflammatory stage may be absent or occur in utero. The skin lesions usually present in four stages: 1) vesicobullous lesions on the limbs and scalp, and frequently on the trunk; 2) verrucous streaks; 3) reticulated hyperpigmentation; and 4) finally a linear hypopigmented band lacking hair and sweating. Other tissues are involved in IP, such as the hair, teeth, nails, eyes, and CNS. CNS involvement occurs in 33%-50% of the cases, presenting as developmental delay, mental retardation, ataxia, spastic paralysis, microcephaly, and seizures. The most common neurologic complication is a seizure occurring on the second or third day of life confined to one side of the body.

Although IP is well-known as an inherited disorder due to mutations in the NEMO gene, it is usually diagnosed just only with pathognomic skin lesions. This report presents a Korean case of a female infant with IP confirmed with NEMO gene mutational analysis showing neonatal seizures and progressive cerebral infarction.

CASE DESCRIPTION

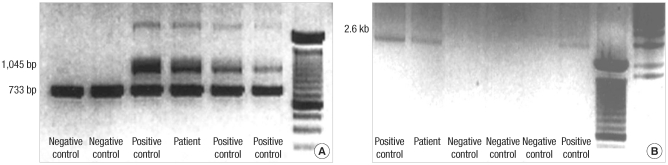

A 3,040 g term female was born in a local obstetrical clinic via a normal vaginal delivery after an uncomplicated pregnancy on May 1, 2009. Her mother was a healthy G2P1 with a healthy 22-month-old son. The baby was 53 cm tall (50-90 percentile) and had a head circumference of 34.3 cm (10-50 percentile), both of which were favorable. During the delivery, the baby was well, although erythematous vesicular eruptions were observed on the upper and lower extremities on the first day of life. On the third day of life, the baby was transferred to our hospital because the skin eruptions increased to cover the entire body, and consisted of erythema and bullae, mostly arranged in lines. The laboratory tests revealed no abnormalities in the full blood count, serum electrolytes, glucose, prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), calcium, magnesium, and C-reactive protein, although the eosinophil count was as high as 44% (normal range 0%-10%). Furthermore, echocardiography, serologic tests for congenital infection, and metabolic screening tests remained normal. An auditory screening test was also normal, while a small focal hemorrhage was seen on the right retina. A biopsy of a vesicle on the arm showed epidermal spongiosis with numerous eosinophils within the epidermis (eosinophilic spongiosis) and some dyskeratotic keratinocytes, consistent with the vesicular stage of IP. Genomic DNA was isolated from the patient's peripheral blood leukocytes. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed to identify the common deletion as either NEMO or ΔNEMO by using two forward primers (Int3s and Rep3s) and one single reverse primer (L2Rev), described by Steffann et al. (1). A 1,045-bp sized product was observed for all the samples, including the patient sample and positive controls, harboring deletions involving exons 4 to 10 of either the NEMO or ΔNEMO (Int3s and L2Rev), whereas a 733-bp product was observed in all tested specimens as an internal amplification control (Rep3s and L2Rev) (Fig. 1A). Confirmatory long-range PCR was also performed to detect the specific genetic rearrangement of the NEMO, described by Bardaro et al. (2). A 2.6-kb product was observed for the pathological NEMO deletion with a forward primer (In2) and a reverse primer (JF3R) (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

PCR-based method to discriminate NEMO gene deletion. (A) Multiplex PCR 1045-bp band corresponding to DNA amplification between Int 3s and L2 Rev primers indicates the presence of the common rearrangement in IP patient only. (B) Confirmatory long-range PCR shows the 2.6-kb band amplified by a forward primer (In2) and a reverse primer (JF3R).

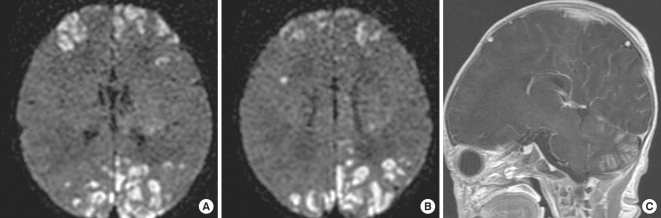

Five days after birth, she developed partial clonic seizures in the right hand and leg lasting for 2 to 3 min. The seizures were treated with phenobarbital and phenytoin. Diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) showed gyriform high-signal-intensity lesions in the parietal, occipital, and frontal lobes of the cerebrum suspected of being bilateral non-hemorrhagic infarctions (Fig. 2A, B). And contrast-enhancement of cerebellar cortex suggested subacute stage of cerebellar infarction (Fig. 2C). The electroencephalogram (EEG) showed rare spikes and sharp waves in the right hemisphere.

Fig. 2.

Initial MRI. (A, B) DWI showed gyriform high-signal-intensity lesions in the parietal, occipital, and frontal lobes of the cerebrum suspected of being bilateral non-hemorrhagic infarctions. (C) Contrast-enhancement of cerebellar cortex suggested subacute stage of cerebellar infarction.

On the 10th day of life, a seizure manifested with apnea and desaturation, and occasional spikes, sharp waves and high-voltage delta waves appeared on the EEG at that time. On follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) showed low-signal-intensity lesions in the corresponding areas (Fig. 3A), and DWI showed more decreased signal-intensity of previous lesions and newly developed high-signal-intensity lesions in both cerebral hemispheres, especially in the periventricular white matter and corpus callosum (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Follow-up MRI obtained on 10th day of birth. (A) ADC showed low-signal-intensity lesions in the corresponding areas. (B) DWI showed more decreased signal-intensity of previous lesions and newly developed high-signal-intensity lesions in both cerebral hemispheres, especially in the periventricular white matter and corpus callosum.

The seizures ceased on the 12th day of life, although the antiepileptic treatment was maintained with phenobarbital. Twenty days after birth, a repeat EEG showed abnormal findings of multiple spikes and sharp waves.

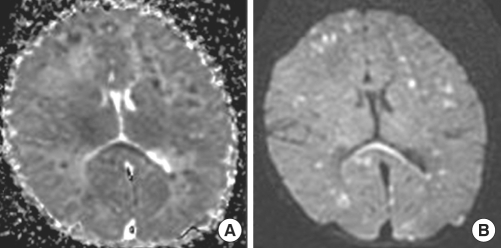

After 3 months, follow-up MRI showed mild encephalomalacia at the sites of the previous infarction in the cortex of both cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres (Fig. 4A). But, severe atrophy of the periventricular white matter and corpus callosum with dilatation of both lateral ventricles was documented (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Follow-up MRI obtained after 3 months. (A) Coronal T1-weighted MRI showed mild encephalomalacia at the sites of the previous infarction in the cortex of both cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres. (B) Axial T1-weight MRI showed high signal lesions from gliosis in periventricular white matter and very thin corpus callosum with dilatation of both lateral ventricles suggesting brain atrophy.

The patient developed left hemiparesis and her skin lesions became verrucous with additional hyperpigmented streaks that developed on the trunk and extremities.

Presently, she is 10 months old and undergoing follow-up care in the pediatrics, ophthalmology, dermatology, and rehabilitation medicine departments.

DISCUSSION

IP is caused by a genomic rearrangement of the NEMO gene at Xq28 and is inherited in an X-linked dominant manner (3). So far, close to 40 distinct NEMO mutations have been identified in IP and recent review reported that about 60%-80% of IP cases had NEMO mutations (4). Most of the studied patients carried a deletion that eliminates exons 4-10 (termed NEMO Δ4-10) and our patient had this deletion.

Though there are many case reports about IP diagnosed based on clinical findings and on histopathological analysis of biopsy specimens (5), there is only one report on mutation analysis in Korean IP patients (6). According to the recent published report from China, they carried out a mutation analysis on 21 clinically diagnosed IP patients. In 21 patients, NEMO mutations were detected in 14 (66.7%) patients with IP, 13 of which were the common exon 4-10 deletion, whereas the other was a novel mutation (7).

As IP is inherited in an X-linked dominant pattern and males (who have only one X chromosome) die in early development, the affected surviving males may have a 47, XXY karyotype, somatic mosaicism, or a mutation that produces a milder form of the condition (8-10). Since the patient's sibling was a healthy 22-month-old male, we wanted to determine whether the patient had inherited the IKBKG mutation from one of the parents or had a de novo mutation. However, we could not undertake the DNA analysis because the parents rejected genetic counseling.

IP patients can show various CNS manifestations (ulegyria, acute destructive encephalopathy, hemorrhagic necrosis, brain edema, and encephalitis with hemorrhagic necrosis), ocular manifestations, orthopedic symptoms, and dental problems, in addition to the characteristic skin lesions (11).

The pathogenesis of the CNS changes in IP is poorly understood, but several mechanisms (vascular, developmental, inflammatory, destructive, and infectious processes) have been proposed based on imaging and histopathologic studies (12). One report suggested a vascular mechanism as the major mechanism, with inflammation as a secondary process. Hennel et al. (13) described magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) changes, consisting of decreased branching and poor filling of the intracerebral vessels, which are indicative of a microangiopathic process; this finding supports the hypothesized vascular origin of the angiopathy and infarction. The retinal vascular abnormalities also support the vascular pathogenic mechanism in IP and show macular vasculopathy and ischemia early on. The retinal vascular changes observed in IP include peripheral retinal vascular non-perfusion, macular infarction, macular neovascularization, and preretinal neovascularization (14). During the ophthalmologic follow-up, our patient had a small focal hemorrhage on the right retina. Although MRA, an important tool for assessing vasculopathy in the CNS, was not performed in this case, we postulate that a microangiopathic process with associated hemorrhagic necrosis occurred, based on the MRI and ophthalmologic findings.

Three-months after birth, follow-up MRI showed mild encephalomalacia in the cortex of the cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres bilaterally, but severe atrophy of the periventricular white matter and corpus callosum with dilatation of the ventricles. Lee et al. (15) evaluated seven IP patients using MRI, and the patients with abnormal changes showed ventricular enlargement, white matter infarcts, cerebral atrophy, hemorrhages and ischemia, and evidence of cerebral infarction. The severe finding of periventricular leukomalacia was found only in premature infants, suggesting global hypoxic damage to preterm infants. Our patient showed encephalomalacia and severe atrophy of the periventricular white matter and corpus callosum with dilatation of the ventricles, although the baby was born at term.

This is a Korean case of a female infant with IP confirmed with NEMO gene mutational analysis. This case also emphasizes that the neurological symptoms and signs in IP patients should be observed because IP can be present in diverse ways ranging from simple skin rashes to severe brain damage, the patients with greater CNS lesions require careful follow-up care involving pediatricians, ophthalmologists, dermatologists, and rehabilitation medicine.

References

- 1.Steffann J, Raclin V, Smahi A, Woffendin H, Munnich A, Kenwrick SJ, Grebille AG, Benachi A, Dumez Y, Bonnefont JP, Hadj-Rabia S. A novel PCR approach for prenatal detection of the common NEMO rearrangement in incontinentia pigmenti. Prenat Diagn. 2004;24:384–388. doi: 10.1002/pd.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bardaro T, Falco G, Sparago A, Mercadante V, Gean Molins E, Tarantino E, Ursini MV, D'Urso M. Two cases of misinterpretation of molecular results in incontinentia pigmenti, and a PCR-based method to discriminate NEMO/IKKgamma dene deletion. Hum Mutat. 2003;21:8–11. doi: 10.1002/humu.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smahi A, Courtois G, Vabres P, Yamaoka S, Heuertz S, Munnich A, Israël A, Heiss NS, Klauck SM, Kioschis P, Wiemann S, Poustka A, Esposito T, Bardaro T, Gianfrancesco F, Ciccodicola A, D'Urso M, Woffendin H, Jakins T, Donnai D, Stewart H, Kenwrick SJ, Aradhya S, Yamagata T, Levy M, Lewis RA, Nelson DL. Genomic rearrangement in NEMO impairs NF-kappaB activation and is a cause of incontinentia pigmenti. The International Incontinentia Pigmenti (IP) Consortium. Nature. 2000;405:466–472. doi: 10.1038/35013114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fusco F, Pescatore A, Bal E, Ghoul A, Paciolla M, Lioi MB, D'Urso M, Rabia SH, Bodemer C, Bonnefont JP, Munnich A, Miano MG, Smahi A, Ursini MV. Alterations of the IKBKG locus and diseases: an update and a report of 13 novel mutations. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:595–604. doi: 10.1002/humu.20739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim BJ, Shin HS, Won CH, Lee JH, Kim KH, Kim MN, Ro BI, Kwon OS. Incontinentia pigmenti: Clinical observation of 40 Korean cases. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21:474–477. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.3.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song MJ, Chae JH, Park EA, Ki CS. The common NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO) gene rearrangement in Korean patients with incontinentia pigmenti. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:1513–1517. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.10.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsiao PF, Lin SP, Chiang SS, Wu YH, Chen HC, Lin YC. NEMO gene mutations in Chinese patients with incontinentia pigmenti. J Formos Med Assoc. 2010;109:192–200. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(10)60042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pacheco TR, Levy M, Collyer JC, de Parra NP, Parra CA, Garay M, Aprea G, Moreno S, Mancini AJ, Paller AS. Incontinentia pigmenti in male patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:251. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franco LM, Goldstein J, Prose NS, Selim MA, Tirado CA, Coale MM, McDonald MT. Incontinentia pigmenti in a boy with XXY mosaicism detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:136–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.11.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kenwrick S, Woffendin H, Jakins T, Shuttleworth SG, Mayer E, Greenhalgh L, Whittaker J, Rugolotto S, Bardaro T, Esposito T, D'Urso M, Soli F, Turco A, Smahi A, Hamel-Teillac D, Lyonnet S, Bonnefont JP, Munnich A, Aradhya S, Kashork CD, Shaffer LG, Nelson DL, Levy M, Lewis RA International IP Consortium. Survival of male patients with incontinentia pigmenti carrying a lethal mutation can be explained by somatic mosaicism or Klinefelter syndrome. The International Incontinentia Pigmenti (IP) Consortium. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:1210–1217. doi: 10.1086/324591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maingay-de Groof F, Lequin MH, Roofthooft DW, Oranje AP, de Coo IF, Bok LA, van der Spek PJ, Mancini GM, Govaert PP. Extensive cerebral infarction in the newborn due to incontinentia pigmenti. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2008;12:284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shuper A, Bryan RN, Singer HS. Destructive encephalopathy in incontinentia pigmenti: a primary disorder? Pediatr Neurol. 1990;6:137–140. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(90)90049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hennel SJ, Ekert PG, Volpe JJ, Inder TE. Insights into the pathogenesis of cerebral lesions in incontinentia pigmenti. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;29:148–150. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(03)00150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg MF, Custis PH. Retinal and other manifestations of incontinentia pigmenti (Bloch-Sulzberger Syndrome) Ophthalmology. 1993;100:1645–1654. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31422-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee AG, Goldberg MF, Gillard JH, Barker PB, Bryan RN. Intracranial assessment of incontinentia pigmenti using magnetic resonance imaging, angiography, and spectroscopic imaging. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:573–580. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170180103019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]