Abstract

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) are hepatic complications associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The expression of mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) on mucosal endothelium is a prerequisite for the development of IBD and it is also detected on hepatic vessels in liver diseases associated with IBD. This aberrant hepatic expression of MAdCAM-1 results in the recruitment of effector cells initially activated in the gut to the liver where they drive liver injury. However the factors responsible for the aberrant hepatic expression of MAdCAM-1 are not known. In this study we show that deamination of methylamine by vascular adhesion protein-1 (VAP-1) [a semicarbazide sensitive amine oxidase (SSAO) expressed in human liver] in the presence of TNFα, induces expression of functional MAdCAM-1 in hepatic endothelial cells and in intact human liver tissue ex-vivo. This is associated with increased adhesion of lymphocytes from patients with PSC to hepatic vessels. Feeding mice methylamine, a constituent of food and cigarette smoke found in portal blood, led to VAP-1/SSAO-dependent MAdCAM-1 expression in mucosal vessels in-vivo.

Conclusion

Activation of VAP-1/SSAO enzymatic activity by methylamine, a constituent of food and cigarette smoke, induces the expression of MAdCAM-1 in hepatic vessels resulting in enhanced recruitment of mucosal effector lymphocytes to the liver. This could be an important mechanism underlying the hepatic complications of IBD.

Introduction

MAdCAM-1 is a 60kDa endothelial cell adhesion molecule that is constitutively expressed on high endothelial venules (HEVs) in Peyer's patches (PPs) and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) and in vessels of the lamina propria (1-3). MAdCAM-1 orchestrates the recruitment of lymphocytes into mucosal tissues via interactions with the α4β7 integrin (4), and is implicated in the sustained destructive gut inflammation that characterizes inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (3). Its importance has been highlighted by the fact that antibodies directed against either MAdCAM-1 or α4β7 attenuate inflammation in animal models and patients with colitis (5, 6) or Crohn's disease (7, 8).

MAdCAM-1 was initially thought to be gut specific molecule (3), but was subsequently found to be induced in the adult human liver in association with portal tract inflammation (9) where it could support the adhesion of α4β7+ gut-derived lymphocytes (10). This aberrant hepatic expression of MAdCAM-1, led to the hypothesis that an entero-hepatic circulation of long-lived mucosal lymphocytes through the liver could trigger extra-intestinal hepatic inflammation in liver diseases complicating IBD (11).

Another molecule potentially involved in this entero-hepatic lymphocyte recirculation is vascular adhesion protein-1 (VAP-1), an adhesion molecule with amine oxidase activity that supports lymphocyte recruitment to the liver (12-14). Substrates for VAP-1 include aliphatic amines, such as methylamine, which can be detected in portal blood as a consequence of food consumption (15). VAP-1 is normally expressed in human liver and weakly on mucosal vessels, however it is rapidly induced in inflamed mucosa in IBD (16). Thus there is complementarity of expression of VAP-1 and MAdCAM-1 molecules. Moreover, previous reports from our group show that deamination of benzylamine by the enzymatic activity of VAP-1 on hepatic endothelium leads to NF-κB activation, increased adhesion molecule expression and enhanced leukocyte adhesion (17). Many studies also support the role of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) in inducing MAdCAM-1 expression (18-20), and because of the colocalization of VAP-1 and MAdCAM-1 on hepatic endothelium and the association of PSC with IBD, we hypothesized that TNFα released from the inflamed gut together with increased levels of methylamine in portal blood could act via VAP-1/SSAO activity to induce hepatic MAdCAM-1 expression. We now show using two in-vitro human models and in-vivo studies in mice that this is the case. We suggest this is a novel mechanism to explain aberrant hepatic MAdCAM-1 expression in patients with IBD and thus an important pathogenic mechanism in liver diseases complicating IBD.

Materials & Methods

Human Tissue and Blood

Human liver tissue was obtained through the Liver Unit at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital. Diseased tissue came from explanted livers removed at transplantation; non-diseased liver from surplus donor tissue or surgical resections of liver tissue containing metastatic tumors in which case uninvolved tissue was taken several centimeters away from any tumor deposits. Whole blood was obtained from patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) with IBD. All human tissue and blood samples were collected with local research ethics committee approval and patient consent.

Isolation and culture of human hepatic endothelial cells (HEC)

Hepatic endothelial cells were isolated from 150g tissue as previously described (14). Briefly, liver tissue was digested enzymatically using collagenase Type 1A (Sigma), filtered and further purified via density gradient centrifugation over 33/77% Percoll™ (Amersham Biosciences). HEC were extracted from the mixed non-parenchymal population initially via negative magnetic selection with HEA-125 (50μg/ml; Progen Biotechnik) to deplete biliary epithelial cells, followed by positive selection with anti-CD31 antibody conjugated to Dynabeads (10μg/ml; Invitrogen, UK). CD31 positive endothelial cells were maintained after isolation in rat-tail collagen (Sigma) coated flasks in complete endothelial media (Gibco, Invitrogen, UK) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated human AB serum (Invitrogen, UK), 10ng/ml of hepatocyte growth factor and 10ng/ml of vascular endothelial growth factor (both from PeproTech). HEC were grown until confluent and used within five passages. The majority of cells isolated by this method expressed markers of sinusoidal endothelium such as L-SIGN and LYVE-1 (21).

In order to determine whether HEC display characteristics consistent with vessels seen in the inflamed liver, we studied the expression of endothelial adhesion molecules using cell-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in HEC from normal (n=3) and diseased (n=3) livers according to standard methodology (14). The protocol and antibodies used are listed in Supplementary Materials and Methods (SM&Ms) and Supplementary Table 1. The expression of CK19 [biliary epithelial cells (BEC)], CK18 (hepatocytes), CD68 (macrophages) and CD11c [dendritic cells (DCs)] markers were used along with CD31 (endothelial cell marker) to confirm purity of HEC cultures by flow cytometry. Antibodies used are presented in SM&Ms and Supplementary Table 2.

Isolation of peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL)

Peripheral venous blood from PSC patients with IBD was collected into EDTA tubes and lymphocytes were isolated by density gradient centrifugation over Lymphoprep (Sigma) according to established methodology (22).

Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

JY cells, a B-lymphoblastoid cell line expressing α4β7 were grown in RPMI1640 (Invitrogen) containing L-glutamine and 10% FCS (Invitrogen).

VAP-1 Dependent MAdCAM-1 Expression

Adenoviral infection of human HEC with VAP-1 constructs

Adenoviral constructs encoding wild-type human (h)VAP-1 and enzymatically inactive hVAP-1 [Tyr(Y)471Phe(F)] have been previously described (23). Before use, the enzymatic activity of VAP-1 transfectants was confirmed by AMPLEX Ultra Red method, described in SM&Ms. HEC were cultured until confluency, washed in PBS to ensure complete removal of human serum and infected with the constructs at optimal multiplicity of infection of 600 for 4 hours in EBM-2 media (Clonetics, Lonza) supplemented with 10% FCS. Transfected cells were then incubated with TNFα (20ng/ml; Peprotech) alone or in combination with methylamine (MA, 50μM; Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 hours.

HEC stimulation with end-products released from methylamine deamination by VAP-1/SSAO

Formaldehyde (HCHO), ammonia (NH3) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) are produced during VAP-1 catalyzed deamination of methylamine. In order to study whether these end-products had a role in induction of MAdCAM-1, non-transfected HEC were exposed to 1μM and 10μM H2O2 (PRoLABO BDH), ammonia (Merck, 8M) or formaldehyde (JT Baker, 13.44M) for 4 hours. In certain experiments, HEC were subjected to repeated dosing with H2O2 (8×10μM at 30min intervals) or to a combination of all three compounds, and their effect on MAdCAM-1 mRNA expression was analyzed. Viability assays confirmed these treatments did not significantly alter endothelial viability after 4 hours treatment.

Humanized VAP-1 mice – VAP-1 dependent signalling in-vivo

Wild-type mice and VAP-1 deficient mice (C57BL/6) expressing enzymatically active or inactive human (h)VAP-1 on the endothelial cells under the control of the mouse tie-1 promoter have been described (24), and were used to study the role of VAP-1 in MAdCAM-1 induction in-vivo. All mice were handled in accordance with the institutional animal care policy of the University of Turku.

Methylamine [0.4% (w/v)] was administered in the drinking water of the animals (freshly made every day) for 14days. After sacrifice, tissue samples from Peyer's patches (PPs) and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) were excised and used for protein and RNA analysis.

Precision Cut Liver Slice Organ Culture

In order to study MAdCAM-1 induction in intact human liver we used a Krumdieck Tissue Slicer (TCS Biologicals) to cut aseptic, 250 microns thick slices of live liver tissue, which could be studied for up to 48 hours ex-vivo. Liver tissue was incubated in Williams E media (Sigma) supplemented with 2% FCS, 0.1μM dexamethasone (Sigma) and 0.5μM insulin (Novo-Nordisk). Tissues were stimulated with methylamine (50μM) and enzymatically active recombinant form of VAP-1 produced in CHO cells (rVAP1, 500ng/ml; Biotie Therapies, Turku, Finland), prior to MAdCAM-1 protein and RNA analysis. The viability of the excised tissue slices was tested by MTT assay (Sigma) before and after the stimulation period (details in SM&Ms).

RNA Analysis

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy mini Kit (Qiagen, UK) and analyzed as described in SM&Ms.

Protein Analysis

MAdCAM-1 protein expression was determined by western blot and immunoprecipitation techniques. Protocols and antibodies used are described in SM&Ms.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

Multicolor fluorescence confocal microscopy was used to localize the expression of MAdCAM-1 in HEC. MAdCAM-1 expression in human liver tissue was investigated in formalin-fixed sucrose-embedded tissues using NovaRed immunostaining. The presence of murine MAdCAM-1 in PPs and MLN was examined by immunofluorescence. Protocols and antibodies used are described in SM&Ms and Supplementary Table 3.

Static Adhesion Assays

Formalin-fixed sucrose-embedded sections (10μm thick) were incubated with JY cells and PBL from PSC patients (n=3) for 30min at room temperature. In certain experiments, tissue sections were incubated with anti-MAdCAM-1 Ab (P1, 1μg/ml; Pfizer) and JY and PBL were blocked with anti-α4β7 (ACT-1, 1μg/ml; gift from M. Briskin, Millenium, USA) for 30min before the static assays. An isotype-matched control antibody (IgG1, 1μg/ml; Dako) was used as negative control. After several washes to remove unbound antibodies, sections were incubated with 105 JY or PSC PBL/100μl, resuspended in RPMI1640 plus 0.1% BSA. Cells were allowed to bind in static conditions at room temperature for 30min, before being washed, fixed in acetone and counterstained using Mayer's haematoxylin (VWR International Ltd). Slides were analyzed by manual counting of adherent lymphocytes in 40 representative high power fields (using x40 objective).

Flow-based Adhesion Assays

The function of MAdCAM-1 protein in-vitro was studied using flow based adhesion assays (17). Briefly, confluent monolayers of HEC were cultured in microcappillaries and stimulated for 2 hours with TNFα and methylamine prior to perfusion of α4β7+ JY cells at a wall shear stress of 0.05Pa. Adherent cells were visualized by phase contrast microscopy (10x objective) and classified as rolling, static or migrated cells. Total adhesion was calculated as cells /mm2 normalized to the number of lymphocytes perfused. In function-blocking experiments HEC were pre-treated with humanized anti-human P1 Ab (5μg/ml) or JY cells were incubated with anti-α4β7 (ACT-1, 1μg/ml) for 30min at 37°C. An isotype-matched control Ab (IgG1, 1μg/ml; Dako) was used as negative control.

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed with Student's t-test when comparing numerical variables between two groups and one-way ANOVA analysis followed by Bonferroni's post-test for comparisons between more than two groups. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Purity and Phenotypic Characterization of HEC

We analyzed the purity of our HEC primary cultures and confirmed that >99% of HEC were CD31+, with very few contaminating non-endothelial cells (Supplementary Figure 1A). As reported previously HEC lack P-selectin but express minimal levels of E-selectin, low levels of VCAM-1 and high constitutive levels of ICAM-1 and CD31, which are all increased upon inflammation (25). We confirmed that under basal conditions HEC isolated from non-diseased (2 resections, 1 normal donor) and diseased (1PSC, 1PBC, primary biliary cirrhosis; 1ALD, alcoholic liver disease) livers adopt a non-activated phenotype expressing similar high levels of ICAM-1 and CD31, low levels of VCAM-1 and E-selectin and no P-selectin (Supplementary Figure 1B). Thus, in this study we grouped the data from all HEC used together.

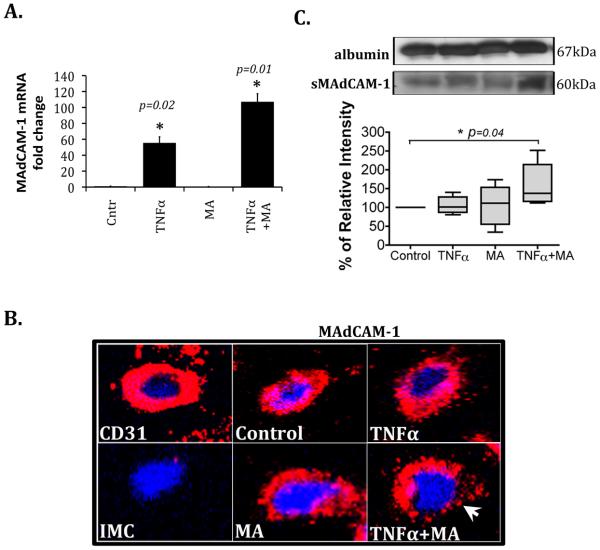

Treatment of HEC with the VAP-1/SSAO Substrate Methylamine and TNFα Induces MAdCAM-1 mRNA Expression, Protein Redistribution onto the Cell Surface and Increased Secretion of Soluble MAdCAM-1

Using quantitative PCR we detected significantly higher MAdCAM-1 mRNA levels in HEC stimulated with TNFα alone and in combination with methylamine compared with non-stimulated HEC (Figure 1A). Total cell MAdCAM-1 protein levels were unaffected by stimulation, and no detectable increase in cytoplasmic MAdCAM-1 was observed either, as confirmed by western blotting and flow cytometry (data not shown). However, using live cell staining and confocal microscopy we observed that MAdCAM-1 protein was redistributed onto the surface of HEC stimulated with TNFα and methylamine (Figure 1B). In addition, we found that MAdCAM-1 was released in a soluble form (sMAdCAM-1) in the supernatant of TNFα and methylamine treated HEC when compared to media alone (Figure 1C). Therefore, we show that methylamine and TNFα upregulate MAdCAM-1 mRNA expression in HEC, induce protein redistribution onto the cell surface and promote increased secretion of soluble MAdCAM-1.

Figure 1.

The physiological VAP-1 substrate methylamine potentiates TNFinduced expression of MAdCAM-1 in hepatic endothelial cells. Endothelial cells were stimulated with TNFα (20ng/ml), methylamine (MA; 50μM) and their combination for 2 hours. (A) mRNA analysis by quantitative PCR. Data represent MAdCAM-1 mRNA n fold change in stimulated HEC versus control (no stimulation) (mean ± SD from n=7 HEC) *p<0.05 vs control by Student's t-test (B) Confocal microscopy images of unstimulated live HEC (control) and HEC stimulated with TNFα and MA, either alone or in combination, showing the localization of MAdCAM-1 protein on the cell surface (in red). CD31 (in red) was used as a positive control and isotype matched control (IMC) antibody as negative. Cell nuclei stained with DAPI (blue). Original magnification x40. White arrow indicates MAdCAM-1 redistribution onto the cell surface after TNFα and MA stimulation. (C) MAdCAM-1 was immunoprecipitated from the cell-culture supernatants of control and 2-hour stimulated cells. Soluble MAdCAM-1 was captured with the polyclonal Ab (H-116) and a 60kDa molecular weight band was detected with the monoclonal Ab (CA102.2C1). Densitometric analysis of n=6 different HEC isolates. Data represent mean percent ± SEM of relative intensity normalized to serum albumin levels and compared to control (set to 100%) *p=0.04 vs sMAdCAM-1 levels in control by Student's t-test.

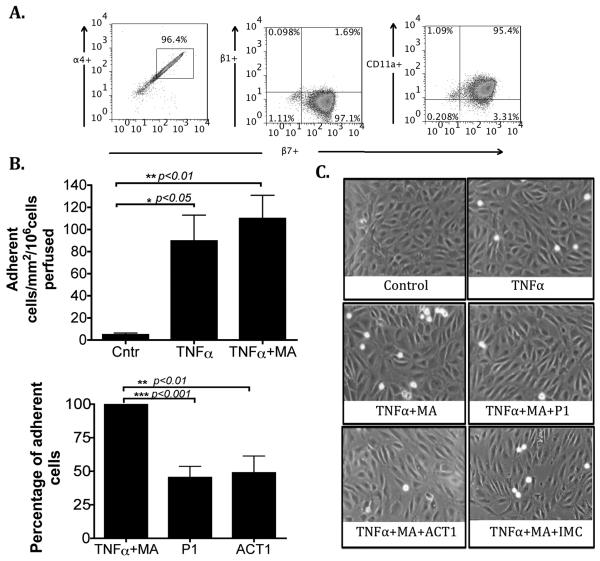

MAdCAM-1 Expressed by HEC is Functionally Active

To study the function of HEC-expressed MAdCAM-1 we used flow-based adhesion assays using JY cells, which express high levels of the MAdCAM-1 receptor α4β7 on the cell surface (Figure 2A). JY cells were perfused over HEC monolayers at 0.05Pa and adhesion was recorded. Under basal conditions no adhesion was detected, however stimulation of HEC with TNFα and methylamine significantly increased the total number of adherent cells and this was reduced by antibody blockade of MAdCAM-1 (P1) or α4β7 (ACT-1)(Figure 2B). The isotype-matched control antibody that was used showed no inhibitory effect [109±21 adherent cells/mm2/106 cells perfused ± SEM in TNFα plus methylamine treated HEC and 116±41 in TNFα plus methylamine plus Isotype control). In combination, our data show that TNFα and methylamine induce redistribution of MAdCAM-1 protein onto the cell surface, rendering it functionally active to support the binding of α4β7+ JY cells.

Figure 2.

MAdCAM-1 expressed by hepatic endothelial cells supports lymphocyte adhesion in a flow based adhesion assay. (A) Representative flow cytometry dot plots showing the coexpression of α4, β1 and CD11a with β7 integrin on JY cells. (B) HEC were treated with TNFα (20ng/ml) alone and in combination with methylamine (MA, 50μM) for 2 hours and JY cells were perfused over the monolayer at a shear stress of 0.05Pa. Adhesion was blocked by function blocking antibodies directed against MAdCAM-1 (P1, 5μg/ml; HEC) or against α4β7 (ACT-1, 1μg/ml; JY cells). Data represent mean adhesion ± SEM from n=7 different HEC *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by Student's t-test. (D) Representative images captured from experimental videos showing adherent cells in absence and presence of function blocking antibodies (P1 and ACT-1) or isotype-matched control (IMC).

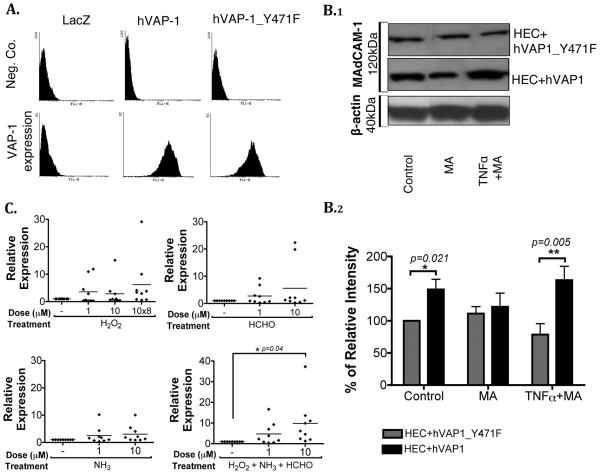

VAP-1/SSAO Enzyme Activity Induces Endothelial Expression of MAdCAM-1 in-vitro

To validate the role of VAP-1/SSAO in MAdCAM-1 induction, we used adenoviral constructs encoding enzymatically active and inactive hVAP-1. The enzyme activities of constructs were confirmed before use (Supplementary Figure 2). Greater than 95% of HEC transfected with adenoviral constructs expressed hVAP-1 on their surface (Figure 3A), with similar median channel fluorescence (MCF) values for both constructs (MCF, 197±40 for hVAP-1 and 216±40 for hVAP-1_Y471F, in n=7 HEC). We then exposed transfected HEC to methylamine and TNFα and observed increased MAdCAM-1 protein levels in HEC transfected with enzymatically active hVAP-1 (Figure 3B.1). In control conditions, the presence of wild-type hVAP-1 caused a significant increase when compared to HEC transfected with the mutant hVAP-1 probably as a consequence of endogenous ligands. When HEC were stimulated with TNFα and methylamine in the presence of hVAP-1 wild-type there was a significant increase in MAdCAM-1 expression compared to HEC transfected with mutant hVAP-1 (Figure 3B.2).

Figure 3.

VAP-1/SSAO induces MAdCAM-1 expression in-vitro. (A) HEC were transfected with adenoviral constructs expressing wild-type hVAP-1 or an enzymatically inactive mutant of hVAP-1 (hVAP-1_Y471F). VAP-1 positivity on transfected HEC was confirmed by flow cytometry using anti-VAP-1 or negative control mouse anti-human antibodies. Data are representative of 7 different HEC. (B) After adenoviral transfection, HEC were stimulated with TNFα (20ng/ml) or methylamine (MA, 50μM) for 2 hours prior to lysis and western blotting. (B.1) Representative blots of 120kDa MAdCAM-1 dimeric protein and 40kDa β-actin. (B.2) Densitometric analysis of n=7 different HEC. Data represent mean percent ± SEM of MAdCAM-1 protein expression normalized to endogenous β-actin levels and shown relative to expression in unstimulated HEC (control) transfected with mutant hVAP-1 (HEC+hVAP-1_Y471F) (set to 100%). Statistical analysis was performed by Student's t-test *p=0.021 vs control HEC+hVAP-1_Y471F, **p=0.005 vs TNFα plus MA stimulated HEC+hVAP-1_Y471F. (C) End-products of VAP-1 enzyme activity induce MAdCAM-1 expression by HEC. Non-transfected HEC were stimulated with single doses of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), formaldehyde (HCHO) and ammonia (NH3) at 1μM and 10μM for 4 hours. Where indicated, HEC were treated repeatedly with 10μM H2O2 (8 times every 30 minutes; 10×8) or with the combination of all three end-products (each at 1μM or 10μM single doses and H2O2 added repeatedly). RNA was extracted from cells and MAdCAM-1 mRNA expression was measured using quantitative PCR. Data represent relative expression of treated versus non-treated HEC (mean shown as a horizontal line, data from n=9 different HEC) *p=0.04 vs control by one-way ANOVA.

To further confirm the role of VAP-1/SSAO in MAdCAM-1 induction, we studied the effects of the end-products released by methylamine deamination by VAP-1. Non-transfected HEC were stimulated with the methylamine metabolites, H2O2, ammonia and formaldehyde for 4 hours, at which time >98% of the cells were viable (data not shown). When H2O2 was administered repeatedly every 30min at 10μM with the other end-products there was a significant 10-fold increase in MAdCAM-1 expression (Figure 3C). Therefore, our data show that the enzymatic activity of VAP-1 can upregulate MAdCAM-1 expression in HEC.

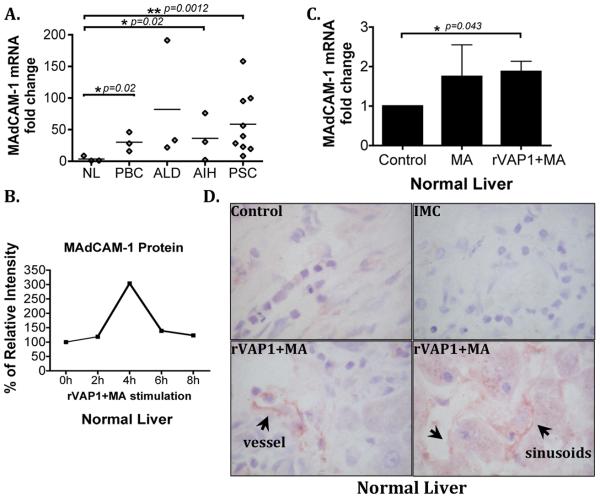

VAP-1/SSAO Induces Human Hepatic MAdCAM-1 Expression Ex-vivo

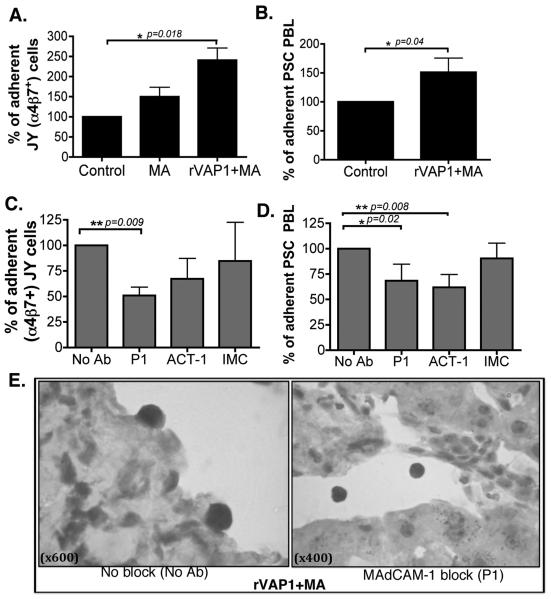

To validate the in-vitro effects of VAP-1/SSAO signalling we used a liver organ culture system in which precision cut viable human liver slices were stimulated with rVAP-1 and methylamine. Initially, we studied the expression of MAdCAM-1 in normal and diseased (PBC, ALD, PSC and AIH) liver tissues and found higher MAdCAM-1 expression levels in chronic liver diseases (Figure 4A), which agreed with previous reports (10). We then stimulated normal liver tissue slices with rVAP-1 and its substrate, methylamine to see whether increased enzyme activity would induce MAdCAM-1 expression. Time course studies detected increased MAdCAM-1 protein expression, which peaked at 4 hours followed by a decline until 8 hours of treatment (Figure 4B). rVAP-1 and methylamine caused a significant increase in MAdCAM-1 mRNA levels in normal liver tissue (n=4) (Figure 4C) and increased MAdCAM-1 protein expression in vessels (Figure 4D). MTT assay also revealed >91% viability after 4-hour stimulation (data not shown). To show that the induced MAdCAM-1 was functional we used static adhesion assays and we demonstrated increased α4β7+ JY cell binding to hepatic vessels in tissues stimulated with rVAP-1 and methylamine (Figure 5A), which was reduced by pre-treatment of tissues with anti-MAdCAM-1 antibody (P1) or lymphocytes with α4β7 (Figure 5C and 5E). We then confirmed the findings using PBL from PSC patients with IBD; these cells adhered efficiently to tissues stimulated with rVAP-1 and methylamine (Figure 5B) and again this was blocked by anti-MAdCAM-1 (P1) and anti-α4β7 (ACT-1) (Figure 5D). Isotype-matched control antibody did not cause any reduction in adhesion (Figures 5C and 5D). Thus, these data confirm that VAP-1/SSAO can induce expression of functionally active human hepatic MAdCAM-1 ex-vivo, which is able to regulate lymphocyte recruitment to the liver.

Figure 4.

MAdCAM-1 is expressed in diseased human liver and expression is increased in normal liver by VAP-1/SSAO activity ex-vivo. (A) MAdCAM-1 mRNA expression in normal (NL; n=3), primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC; n=3), alcoholic liver disease (ALD; n=3), autoimmune hepatitis (AIH; n=3) and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC; n=9) liver tissues. MAdCAM-1 mRNA levels (mean±SD) in diseased livers relative to normal liver tissues (mean shown as a horizontal line). *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs expression in normal liver (NL) by unpaired Student's t-test. (B) Normal liver tissue slices were stimulated with rVAP-1 (500ng/ml) and methylamine (MA, 50μM) for 0 to 8 hours and MAdCAM-1 protein was analyzed by western blotting. Data represent percentage of MAdCAM-1 protein expression normalized to endogenous β-actin levels. (C) Precision cut normal 250μm liver tissue slices from four different livers were stimulated with MA and rVAP-1 for 4 hours and MAdCAM-1 mRNA expression was analyzed by qPCR. MAdCAM-1 mRNA fold change in treated versus control samples is shown. Student's t-test *p<0.05 vs control. (D) MAdCAM-1 protein expression in vessels and sinusoids (black arrows) on representative normal liver untreated (control) or stimulated with MA and rVAP-1. IMC=Isotype matched control antibody. Original magnification x600.

Figure 5.

MAdCAM-1 induced in normal liver supports adhesion of JY cells and PBL from PSC patients. Static adhesion assays showing adhesion of (A) α4β7 positive JY cells and (B) peripheral blood lymphocytes from PSC patients, to normal liver sections cut from precision cut liver slices, after 4 hours stimulation with rVAP-1 and MA. Data represent mean adhesion ± SEM from n=4 normal livers and from n=3 PSC PBL. (C and D) Binding was inhibited when MAdCAM-1 (P1; 1μg/ml) and α4β7 (ACT-1; 1μg/ml) were blocked. Data show percent adherent cells compared with control samples and when blocking was used data show the percent adherent cells compared to adhesion in samples where no antibody was used (No Ab). Isotype-matched control (IMC) used at 1μg/ml. Student's t-test *p<0.01, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. (E) Representative immunostaining pictures showing adherent lymphocytes in rVAP-1 and MA stimulated normal liver tissue and non-adhering lymphocytes on tissues where MAdCAM-1 was blocked (P1). Images were acquired at original magnification of x600 and x400, respectively.

VAP-1/SSAO Induces MAdCAM-1 Expression In-vivo

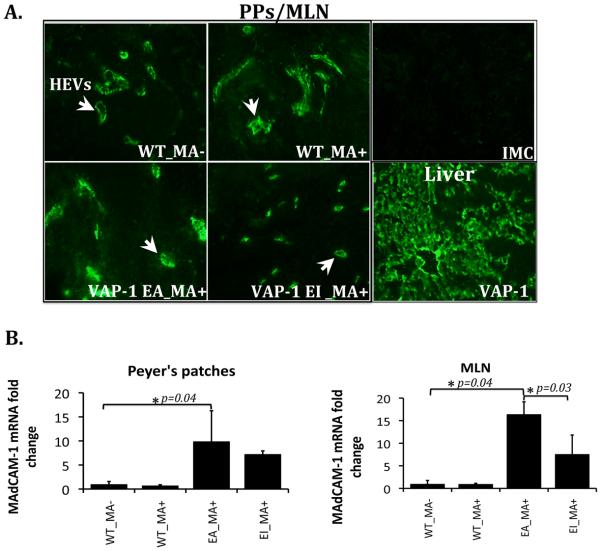

To investigate the role of VAP-1/SSAO dependent methylamine deamination in MAdCAM-1 expression in-vivo, we used wild-type mice (WT) and VAP-1 deficient mice expressing hVAP-1 in either an enzymatically active (VAP-1_EA) or inactive (VAP-1_EI) form, as a transgene in endothelial cells. The presence of hVAP-1 in the livers of transgenic animals was confirmed by immunofluorescent staining (Figure 6A). To test whether methylamine could alter MAdCAM-1 expression in-vivo, it was given to the animals through their drinking water for 14 days. We were unable to detect MAdCAM-1 mRNA or protein in murine liver both before and after stimulation in all animal models using mRNA analysis, western blotting and immunofluorescence (data not shown). However, we detected a significant 10-fold and 16-fold increase in MAdCAM-1 mRNA levels and increased MAdCAM-1 protein in Peyer's patches and mesenteric lymph nodes, in transgenic animals expressing enzymatically active hVAP-1 following methylamine administration (Figure 6A and 6B). The importance of VAP-1/SSAO in this induction was confirmed by studies showing reduced MAdCAM-1 mRNA induction in mice expressing the enzymatically inactive form of hVAP-1 (Figure 6B). Therefore, these data demonstrate the ability of VAP-1 enzyme activity to induce MAdCAM-1 expression in gut mucosal vessels in-vivo.

Figure 6.

VAP-1/SSAO induces MAdCAM-1 expression in-vivo. Wild type mice (WT) and VAP-1 deficient mice expressing enzymatically active (VAP-1_EA) and inactive (VAP-1_EI) human VAP-1, were supplied with 0.4% (w/v) methylamine (MA+) in their drinking water for 14 days. Wild type mice without methylamine treatment were controls (WT_MA−). (A) Immunofluorescent staining of MAdCAM-1 in high endothelial venules (HEVs) (white arrows) of Peyer's patches (PPs) and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) and in-vivo expression of human VAP- 1 in the liver of transgenic mice. Isotype-matched control (IMC) antibody was used as a negative control. (B) MAdCAM-1 mRNA analysis using real-time PCR. Data represent MAdCAM-1 mRNA fold change (mean±SD) in PPs and MLN in mice (n=3 in each group) receiving methylamine compared with wild-type mice that had not received methylamine (WT_MA−; n=3). *p<0.04 by Student's t-test in EA_MA+ vs WT_MA− in both PPs and MLN and *p=0.03 by Student's t-test in EA_MA+ vs EI_MA+ in MLN.

Discussion

The ability of aberrantly expressed hepatic MAdCAM-1 to recruit mucosal T cells to the liver in PSC (9, 10), led us to further investigate factors involved in hepatic MAdCAM-1 induction. In this study, we provide evidence that VAP-1/SSAO dependent oxidation of methylamine increases MAdCAM-1 expression in hepatic endothelial cells in-vitro and ex-vivo and in mucosal vessels in-vivo. These findings implicate VAP-1/SSAO activity in inducing and maintaining MAdCAM-1 expression in the gut and the liver.

Although provision of the VAP-1 substrate methylamine or TNFα led to induction of MAdCAM-1 the combination of stimuli had an additive effect. The role of TNFα in MAdCAM-1 induction has been reported previously using both in-vitro and in-vivo systems (18-20). However, it is unlikely that TNFα alone is sufficient to induce hepatic MAdCAM-1 in-vivo, since hepatic MAdCAM-1 expression is limited with the strongest most consistent expression seen in PSC and autoimmune hepatitis complicating IBD (10). This led us to look for other factors that may have a particular role in the liver. VAP-1 is constitutively expressed in the human liver and we have previously reported that the enzymatic activity of VAP-1 generates products including H2O2 that can activate NF-κB-dependent adhesion molecule expression (17). This led us to hypothesize that the VAP-1/SSAO enzymatic activity could also promote MAdCAM-1 expression. We now confirm this is the case and we further demonstrate that the natural VAP-1/SSAO substrate, methylamine, which is present in food, wine and cigarette smoke is able to increase MAdCAM-1 expression in-vitro, in-vivo and ex-vivo.

Human hepatic endothelial cells exposed to TNFα and methylamine showed increased MAdCAM-1 mRNA transcription, protein redistribution onto the cell surface and increased secretion of soluble MAdCAM-1 protein. Using flow-based adhesion assays we confirmed that methylamine/TNFα induced MAdCAM-1 on HEC was functionally active, able to support increased adhesion of α4β7 expressing JY cells. There was a residual binding of JY cells after MAdCAM-1 or α4β7 blocking, which we believe was LFA-1/ICAM-1 mediated. We also found that TNFα and methylamine stimulation induced the production of a soluble form of MAdCAM-1. Leung et al. (26) first reported soluble MAdCAM-1 in human serum, urine and other biological fluids but it is not known whether this soluble form is functional. Soluble forms of other adhesion molecules including E-selectin and VAP-1 have the ability to enhance adhesion to endothelium (27, 28). Therefore, sMAdCAM-1 produced via the action of VAP-1/SSAO could also serve as an attractant increasing leukocyte adhesion.

As well as functioning as an adhesion molecule VAP-1 is also an enzyme leading us to investigate whether this enzyme activity is critical for MAdCAM-1 induction. We present several pieces of experimental data to support this: 1) the provision of methylamine and TNFα to HEC over-expressing enzymatically active hVAP-1 increased MAdCAM-1 expression whereas HEC expressing enzymatically inactive hVAP-1 did not respond 2) treatment of HEC with the end-products of VAP-1 deamination of methylamine, formaldehyde, ammonia and H2O2 increased MAdCAM-1 expression 10-fold. Local H2O2 has been implicated in the regulation of adhesion molecule expression (29-32). We have reported that the end-products of SSAO deamination including H2O2 induce expression of endothelial E- and P-selectins in vascular endothelium (32) and of ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and CXCL8 in human hepatic sinusoidal endothelium through stimulation of the PI3K, MAPK and NF-κB pathways (17). Thus H2O2 released as a consequence of methylamine deamination by VAP-1 could operate through the NF-κB binding elements present in the hMAdCAM-1 promoter region (33) to induce MAdCAM-1 expression.

The studies using primary hepatic endothelial cells were compelling but we wanted to see if methylamine could induce functional MAdCAM-1 in intact liver tissue. To do this we used a novel liver organ culture system in which we can culture viable human liver tissue slices for up to 48 hours ex-vivo. Addition of methylamine to cultures of normal human liver resulted in VAP-1/SSAO-dependent induction of MAdCAM-1 RNA and protein on hepatic endothelium. Furthermore we were able to confirm that the induced MAdCAM-1 was functional since it supported the adhesion of peripheral blood lymphocytes from patients with PSC to vessels in the tissue slices via the α4β7 integrin, which is expressed by up to 40% of circulating T cells in patients with PSC (34).

Finally, we wanted to confirm the ability of VAP-1/SSAO to induce MAdCAM-1 in-vivo. To do this we used mice but found that we were unable to detect or induce any MAdCAM-1 in murine liver. This finding agreed with reports from Bonder et al. (13), in which they failed to detect MAdCAM-1 in murine portal venules and sinusoids after Concavalin A administration. This is a clear difference between mice and humans and might explain why it has been difficult to develop a representative murine model of PSC. However, MAdCAM-1 is expressed in mucosal vessels in mice, where it is increased by inflammation. We now report that methylamine feeding increased MAdCAM-1 expression in high endothelial venules of Peyer's patches and mesenteric lymph nodes and we confirmed that this induction was dependent on the enzymatic activity of VAP-1/SSAO, because over-expression of enzymatically active endothelial VAP-1 in transgenic animals led to a significant increase in MAdCAM-1 which was reduced in animals expressing enzymatically inactive hVAP-1. Interestingly, wild-type animals did not show consistent responses to methylamine, which probably reflects the relatively low levels of VAP-1/SSAO present in the absence of inflammation. Surprisingly, increased levels of MAdCAM-1 were detected in transgenic animals expressing enzymatically inactive hVAP-1. Although these levels were not generally as high as those seen in mice over-expressing enzymatically intact hVAP-1, we suggest that VAP-1 might also induce MAdCAM-1 by acting as an adhesion molecule to recruit lymphocytes that then secrete factors that promote MAdCAM-1 induction.

In conclusion, our data reveal that VAP-1/SSAO contributes to MAdCAM-1 induction in hepatic endothelial cells in-vitro and ex-vivo in man and in gut mucosal vessels in-vivo in mice. Based on this finding and previous reports, which describe the induction of VAP-1 during gut inflammation (16), we suggest that increased levels of methylamine due to enhanced absorption via the inflamed gut or from cigarette smoke (15) act as substrates for VAP-1/SSAO leading to MAdCAM-1 expression in the inflamed gut mucosa and hepatic endothelium. This could promote the uncontrolled recruitment of mucosal effector cells, resulting in tissue damage that is characteristic of both IBD and its hepatic complications. Thus, targeting VAP-1/SSAO therapeutically could not only reduce lymphocyte adhesion directly but could also downregulate MAdCAM-1 expression leading to resolution of both liver and gut inflammation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the sponsors of this work, Marie Curie Early Training Program, Wellcome Trust, the Finnish Academy, the Sigrid Juselius Foundation and the NIHR Liver BRU. We would also like to thank K. Auvinen for their practical advice and R. Sjoroos for her expert technical assistance in using the adenoviruses. Finally, we kindly thank M. Briskin for his critical review of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Briskin MJ, McEvoy LM, Butcher EC. MAdCAM-1 has homology to immunoglobulin and mucin-like adhesion receptors and to IgA1. Nature. 1993;363:461–464. doi: 10.1038/363461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shyjan AM, Bertagnolli M, Kenney CJ, Briskin MJ. Human mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) demonstrates structural and functional similarities to the alpha 4 beta 7-integrin binding domains of murine MAdCAM-1, but extreme divergence of mucin-like sequences. J Immunol. 1996;156:2851–2857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briskin M, Winsor-Hines D, Shyjan A, Cochran N, Bloom S, Wilson J, McEvoy LM, et al. Human mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 is preferentially expressed in intestinal tract and associated lymphoid tissue. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:97–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Girard JP, Springer TA. High endothelial venules (HEVs): specialized endothelium for lymphocyte migration. Immunol Today. 1995;16:449–457. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feagan BG, Greenberg GR, Wild G, Fedorak RN, Pare P, McDonald JW, Dube R, et al. Treatment of ulcerative colitis with a humanized antibody to the alpha4beta7 integrin. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2499–2507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamann A, Andrew DP, Jablonski-Westrich D, Holzmann B, Butcher EC. Role of alpha 4-integrins in lymphocyte homing to mucosal tissues in vivo. J Immunol. 1994;152:3282–3293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feagan BG, Greenberg GR, Wild G, Fedorak RN, Pare P, McDonald JW, Cohen A, et al. Treatment of active Crohn's disease with MLN0002, a humanized antibody to the alpha4beta7 integrin. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1370–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guagnozzi D, Caprilli R. Natalizumab in the treatment of Crohn's disease. Biologics. 2008;2:275–284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hillan KJ, Hagler KE, MacSween RN, Ryan AM, Renz ME, Chiu HH, Ferrier RK, et al. Expression of the mucosal vascular addressin, MAdCAM-1, in inflammatory liver disease. Liver. 1999;19:509–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.1999.tb00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant AJ, Lalor PF, Hubscher SG, Briskin M, Adams DH. MAdCAM-1 expressed in chronic inflammatory liver disease supports mucosal lymphocyte adhesion to hepatic endothelium (MAdCAM-1 in chronic inflammatory liver disease) Hepatology. 2001;33:1065–1072. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eksteen B, Miles AE, Grant AJ, Adams DH. Lymphocyte homing in the pathogenesis of extra-intestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Med. 2004;4:173–180. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.4-2-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith DJ, Salmi M, Bono P, Hellman J, Leu T, Jalkanen S. Cloning of vascular adhesion protein 1 reveals a novel multifunctional adhesion molecule. J Exp Med. 1998;188:17–27. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonder CS, Norman MU, Swain MG, Zbytnuik LD, Yamanouchi J, Santamaria P, Ajuebor M, et al. Rules of recruitment for Th1 and Th2 lymphocytes in inflamed liver: a role for alpha-4 integrin and vascular adhesion protein-1. Immunity. 2005;23:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lalor PF, Edwards S, McNab G, Salmi M, Jalkanen S, Adams DH. Vascular adhesion protein-1 mediates adhesion and transmigration of lymphocytes on human hepatic endothelial cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:983–992. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.2.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pirisino R, Ghelardini C, Banchelli G, Galeotti N, Raimondi L. Methylamine and benzylamine induced hypophagia in mice: modulation by semicarbazide-sensitive benzylamine oxidase inhibitors and aODN towards Kv1.1 channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:880–886. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salmi M, Kalimo K, Jalkanen S. Induction and function of vascular adhesion protein-1 at sites of inflammation. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2255–2260. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lalor PF, Sun PJ, Weston CJ, Martin-Santos A, Wakelam MJ, Adams DH. Activation of vascular adhesion protein-1 on liver endothelium results in an NF-kappaB-dependent increase in lymphocyte adhesion. Hepatology. 2007;45:465–474. doi: 10.1002/hep.21497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ando T, Langley RR, Wang Y, Jordan PA, Minagar A, Alexander JS, Jennings MH. Inflammatory cytokines induce MAdCAM-1 in murine hepatic endothelial cells and mediate alpha-4 beta-7 integrin dependent lymphocyte endothelial adhesion in vitro. BMC Physiol. 2007;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogawa H, Binion DG, Heidemann J, Theriot M, Fisher PJ, Johnson NA, Otterson MF, et al. Mechanisms of MAdCAM-1 gene expression in human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C272–281. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00406.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujiyama Y, Hokari R, Miura S, Watanabe C, Komoto S, Oyama T, Kurihara C, et al. Butter feeding enhances TNF-alpha production from macrophages and lymphocyte adherence in murine small intestinal microvessels. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1838–1845. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aspinall AI, Curbishley SM, Lalor PF, Weston CJ, Blahova M, Liaskou E, Adams RM, et al. CX(3)CR1 and vascular adhesion protein-1-dependent recruitment of CD16(+) monocytes across human liver sinusoidal endothelium. Hepatology. 2010;51:2030–2039. doi: 10.1002/hep.23591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miles A, Liaskou E, Eksteen B, Lalor PF, Adams DH. CCL25 and CCL28 promote alpha4 beta7-integrin-dependent adhesion of lymphocytes to MAdCAM-1 under shear flow. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G1257–1267. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00266.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koskinen K, Vainio PJ, Smith DJ, Pihlavisto M, Yla-Herttuala S, Jalkanen S, Salmi M. Granulocyte transmigration through the endothelium is regulated by the oxidase activity of vascular adhesion protein-1 (VAP-1) Blood. 2004;103:3388–3395. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stolen CM, Marttila-Ichihara F, Koskinen K, Yegutkin GG, Turja R, Bono P, Skurnik M, et al. Absence of the endothelial oxidase AOC3 leads to abnormal leukocyte traffic in vivo. Immunity. 2005;22:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lalor PF, Shields P, Grant A, Adams DH. Recruitment of lymphocytes to the human liver. Immunol Cell Biol. 2002;80:52–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2002.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leung E, Lehnert KB, Kanwar JR, Yang Y, Mon Y, McNeil HP, Krissansen GW. Bioassay detects soluble MAdCAM-1 in body fluids. Immunol Cell Biol. 2004;82:400–409. doi: 10.1111/j.0818-9641.2004.01247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurkijarvi R, Adams DH, Leino R, Mottonen T, Jalkanen S, Salmi M. Circulating form of human vascular adhesion protein-1 (VAP-1): increased serum levels in inflammatory liver diseases. J Immunol. 1998;161:1549–1557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lo SK, Lee S, Ramos RA, Lobb R, Rosa M, Chi-Rosso G, Wright SD. Endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecule 1 stimulates the adhesive activity of leukocyte integrin CR3 (CD11b/CD18, Mac-1, alpha m beta 2) on human neutrophils. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1493–1500. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patel KD, Zimmerman GA, Prescott SM, McEver RP, McIntyre TM. Oxygen radicals induce human endothelial cells to express GMP-140 and bind neutrophils. J Cell Biol. 1991;112:749–759. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.4.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bradley JR, Johnson DR, Pober JS. Endothelial activation by hydrogen peroxide. Selective increases of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and major histocompatibility complex class I. Am J Pathol. 1993;142:1598–1609. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lo SK, Janakidevi K, Lai L, Malik AB. Hydrogen peroxide-induced increase in endothelial adhesiveness is dependent on ICAM-1 activation. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:L406–412. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1993.264.4.L406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jalkanen S, Karikoski M, Mercier N, Koskinen K, Henttinen T, Elima K, Salmivirta K, et al. The oxidase activity of vascular adhesion protein-1 (VAP-1) induces endothelial E- and P-selectins and leukocyte binding. Blood. 2007;110:1864–1870. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-069674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leung E, Berg RW, Langley R, Greene J, Raymond LA, Augustus M, Ni J, et al. Genomic organization, chromosomal mapping, and analysis of the 5' promoter region of the human MAdCAM-1 gene. Immunogenetics. 1997;46:111–119. doi: 10.1007/s002510050249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eksteen B, Grant AJ, Miles A, Curbishley SM, Lalor PF, Hubscher SG, Briskin M, et al. Hepatic endothelial CCL25 mediates the recruitment of CCR9+ gut-homing lymphocytes to the liver in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1511–1517. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.