Abstract

Motivation: Predicting protein interactions involving peptide recognition domains is essential for understanding the many important biological processes they mediate. It is important to consider the binding strength of these interactions to help us construct more biologically relevant protein interaction networks that consider cellular context and competition between potential binders.

Results: We developed a novel regression framework that considers both positive (quantitative) and negative (qualitative) interaction data available for mouse PDZ domains to quantitatively predict interactions between PDZ domains, a large peptide recognition domain family, and their peptide ligands using primary sequence information. First, we show that it is possible to learn from existing quantitative and negative interaction data to infer the relative binding strength of interactions involving previously unseen PDZ domains and/or peptides given their primary sequence. Performance was measured using cross-validated hold out testing and testing with previously unseen PDZ domain–peptide interactions. Second, we find that incorporating negative data improves quantitative interaction prediction. Third, we show that sequence similarity is an important prediction performance determinant, which suggests that experimentally collecting additional quantitative interaction data for underrepresented PDZ domain subfamilies will improve prediction.

Availability and Implementation: The Matlab code for our SemiSVR predictor and all data used here are available at http://baderlab.org/Data/PDZAffinity.

Contact: gary.bader@utoronto.ca; dengnaiyang@cau.edu.cn

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Modular domains are the major building blocks of eukaryotic proteins and interaction networks (Pawson and Nash, 2003). These domains usually fold independently and are present in various combinations within a single protein to create a rich repertoire of functionally diverse proteins from a more limited domain set (Vogel et al., 2004). An important subclass of these domains, peptide recognition modules (PRMs), bind to short extended and linear peptide segments in target proteins to mediate protein–protein interactions in eukaryotic cell signaling systems (Pawson and Nash, 2003). Characterizing the interactions of these peptide recognition modules will help us map and understand the many biological processes they mediate.

PRMs generally bind their peptide ligands in the weak (10 μM) affinity (binding strength) range (Castagnoli et al., 2004), and sensitive in vitro experimental techniques like phage display (Tonikian et al., 2008, 2009) and peptide/protein microarrays (Jones et al., 2006; Stiffler et al., 2006) have been used to map the binding specificities and protein interactions of large sets of SH3 (Landgraf et al., 2004; Tonikian et al., 2009), SH2 (Huang et al., 2008; Jones et al., 2006), WW (Hu et al., 2004) and PDZ (Stiffler et al., 2006, 2007; Tonikian et al., 2008) domains. However, these experimental techniques are resource intensive, and cannot be readily applied to new members and alleles of PRMs that are increasingly being collected by genome sequencing projects and population-based genetic variation studies (The International HapMap Consortium, 2007). Ideally, a computational model could be developed to predict whether a PRM will bind to a peptide given their primary sequences. Such a model could be used to predict protein interactions from newly sequenced genomes and the effect of mutations on known PRM-mediated protein interactions to guide subsequent experimental characterization. Computational domain–peptide interaction prediction has been studied for multiple PRMs, such as SH3 (Ferraro et al., 2006; Yaffe et al., 2001), SH2 (Sanchez et al., 2008; Wunderlich and Mirny, 2009), PDZ (Chen et al., 2008), WW (Schleinkofer et al., 2004) and MHC domains (Jacob and Vert, 2008; Nielsen et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009) (which are a special case of peptide binding domains that do not mediate protein–protein interactions). These approaches, except for some MHC studies and the pioneering work of Chen et al. (2008), predict binding qualitatively—i.e. whether or not a domain–peptide pair will bind.

To gain a better understanding of in vivo protein interaction networks, we also need to know the strength of domain–peptide binding, not just whether they bind or not. This information can help us understand the competition among multiple potential interactors for the same protein in the cell. Binding strength is also an important factor in the fine-tuning of many regulatory processes, such as the affinity-driven sequential phosphorylation of residues on the FGF receptor (Lew et al., 2009), the affinity-driven sequential activation of genes targeted by a common transcription factor (Chechik et al., 2008) and the fine-tuning of the HOG pathway in response to osmolarity stress (Zarrinpar et al., 2003). Whereas large sets of quantitative data have permitted quantitative prediction of MHC–peptide interactions for MHC domains through data-driven machine learning approaches (Nielsen et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009), sufficient quantitative interaction data has only recently become available to enable similar computational approaches for modular interaction domains involved in cellular signaling (Stiffler et al., 2007).

The first PRM with large-scale affinity data available is the PDZ domain (Stiffler et al., 2007). PDZ-containing proteins are important in ion channel and receptor regulation, cell polarity, neural development, and often act as scaffolds to organize the assembly of protein complexes in cell signaling pathways in normal and disease situations (Cushing et al., 2008; Nourry et al., 2003). Here, we develop a computational method, trained on the set of interaction data measured in Stiffler et al. (2007) to quantitatively predict PDZ domain–peptide interactions involving previously unseen PDZ domains and/or peptides from their primary sequences.

Interaction data generated in Stiffler et al. (2007) consists of a positive dataset of PDZ domain–peptide interactions with binding affinity measurements and a negative dataset (non-interacting PDZ domain–peptide pairs, with no binding affinity measurements). Intuitively, the negative interaction data provide qualitative information on the contribution of amino acids to binding affinity that could improve quantitative prediction. Popularly used position weight matrix (PWM) and conventional regression methods like support vector regression (SVR), however, cannot incorporate qualitative negative data. Here, we devised a novel extension of SVR, termed SemiSVR, that considers both quantitative positive and qualitative negative interaction data. We show that SemiSVR, being able to incorporate negative data, is better than SVR and PWM in identifying the stronger interactor among previously unseen peptides. Next, through a feature-encoding framework that considers both the primary sequence of PDZ domains and peptides, we applied SemiSVR to predict relative binding strength of PDZ domain–peptide interactions involving previously unseen PDZ domains. We find that SemiSVR's performance is superior to a previously published method on the same dataset (Chen et al., 2008) and the naïve usage of PWM from sequence-similar PDZ domains.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Data

Our training data is that published in Chen et al. (2008), which is a cleaned subset of interactions with measured affinities originally reported by Stiffler et al. (2007), containing interactions between 82 mouse PDZ domains and 217 mouse genome-derived (genomic) peptides. Briefly, interactions were assessed using a peptide microarray followed by confirmation of positives and measurement of binding affinities by fluorescence polarization (FP), a high-quality affinity measurement method (Stiffler et al., 2007). This resulted in 560 PDZ domain–peptide interactions, involving 82 mouse PDZ domains and 93 peptides, and 1167 negative interactions, involving 82 mouse PDZ domains and 138 peptides, which were confirmed by FP. The 560 positive interactions have measured affinities (each measured as a dissociation constant, Kd) of less than 100 μM (high Kd indicates weak interaction and low Kd indicates strong interaction, see Supplementary Fig. S1 for distribution of the KDs) while the affinities of the non-binding pairs are identified to be greater than the threshold (100 μM), but Kd values are not measured. We call the mixture of both quantitative (positive interactions) and qualitative (negative interactions) ‘semi-quantitative’ data. The number of binding peptides per PDZ domain varies widely. Among the 82 domains, 23 have at least 10 binding peptides, which we use for training (Supplementary Table S1).

2.2 Predictor

We wish to predict quantitative PDZ domain–peptide interactions based on known interactions and affinity data. To do this, we developed a new method called Semi-quantitative SVR (SemiSVR), a novel extension of SVR, to learn how to predict the binding affinity of PDZ domain–peptide interactions from both quantitative binding (positive) data and qualitative non-binding (negative) data (Fig. 1). SVR is an established machine learning method for non-linear regression (Smola and Scholkopf, 2004). We extended this method to take advantage of negative information we have available, which is not considered by other regression-based methods. In non-linear regression, the regression function (f) is approximated by a kernel function K(x, y) as follows:

| (1) |

where xi is the known training data, and α=(α1, α2,…, αm)T (T =transpose, m = training dataset size) is the Lagrange multiplier and b is the bias threshold. The SemiSVR aims to determine the unknown multiplier α and the bias b based on the training data. Given the training dataset S={(xi, yi):xi ∈ Rn, yi ∈ R}i=1m ∪ {zj : zj ∈ Rn}j=1k, where xi, zj are the input features for the positive and negative PDZ domain–peptide pairs, respectively, yi is the affinity for positive quantitative data xi, and the regression value for the training data zj is greater than a threshold (i.e. ŷ = 100 μM).

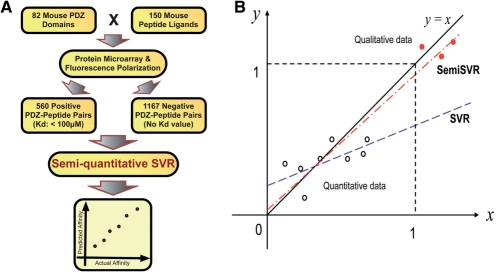

Fig. 1.

Overview of the quantitative prediction method. (A) Positive and negative PDZ domain–peptide pairs were previously determined by a combination of protein microarray and fluorescence polarization experiments. PDZ domain and peptide features calculated from primary sequence information were used to construct a quantitative binding predictor using our novel semi-quantitative support vector regression (SemiSVR) method, where negative data are used to help regression learning. (B) Conceptual illustration of how SemiSVR works. Sample data for illustration purposes were generated using the function: y=x (black solid line) with normally distributed noise. Quantitative data (positive) are shown as open black circles while the qualitative data (negative) are shown as filled red circles. The SemiSVR method (red dashed dot line), which considers the quantitative data and qualitative data, better learns the function (y=x) used to generate the input data compared with the SVR method (blue dashed line), which only considers the quantitative data (open circles). In this way, incorporating qualitative negative data using SemiSVR improves quantitative prediction.

For the positive quantitative data xi, we wish to minimize the ε-insensitive loss function-based error criterion that leads to |f(xi)−yi|≤ε, that is the regression values f(xi) on the training data xi should have less error than ε, i = 1, 2,…, m. For the negative qualitative data zj, we wish to make the regression value f(zj) on these data satisfy the prior knowledge [i.e. the regression value f(zj) is greater than the threshold ŷ = 100 μM]:  and

and  , j = 1, 2,…, k.

, j = 1, 2,…, k.

The above constraints assume that the final regression function f(x) can approximate all the data (S) with ε precision. Sometimes, however, we want to allow for some errors. As with standard SVR, a slack variable ξ and  can be introduced to cope with otherwise unsatisfiable constraints. Considering all of this and similar to previous work on knowledge-based non-linear kernel approximation (Mangasarian and Wild, 2007), the linear programming form of Semi-quantitative SVR is given as:

can be introduced to cope with otherwise unsatisfiable constraints. Considering all of this and similar to previous work on knowledge-based non-linear kernel approximation (Mangasarian and Wild, 2007), the linear programming form of Semi-quantitative SVR is given as:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

where ε is a user-defined constant that contributes to the ε-insensitive loss function, which measures the error of the regression on the training data, and is defined as |ξ|ε=0, if |ξ| < ε, and equal to |ξ| − ε, otherwise. C1, C2 > 0 are the penalty parameters determining the trade-off between the regularization term (in order to avoid overfitting) and the empirical error (according to ε-insensitive loss function). Here, we drive the error down by minimizing the 1-norm of the errors and together with the 1-norm of α for complexity reduction or stabilization. Previous work shows the alternative 1-norm for 2-norm regularization achieves equivalent performance (see Mangasarian et al., 2004; 2007). Constraints (3–4) ensure that the positive pairs lie in ε-precision with some allowed errors while constraints (5–7) ensure the negative pairs satisfy the prior knowledge within some allowed errors. In practice, all affinities are scaled to the range [−1, 1] after taking log10, which makes the data easier to work with. We select parameters C1, C2, ε and the kernel parameters (σ or p) using grid search (Chang and Lin, 2001).

The input of the semi-quantitative SVR model is the encoded representation of the PDZ domain–peptide pair (see below) and the corresponding binding affinity while the output is the predicted affinity score for each pair. (Higher scores mean weaker interaction while lower scores mean stronger interaction, similar to the scale of biochemical KDs). All software was developed in Matlab 2008 and source code is available on the web site (http://baderlab.org/Data/PDZAffinity).

As a benchmark, we also developed a nearest neighbor SemiSVR for each test PDZ domain that was trained on the closest PDZ domain with both its binding and non-binding peptides. We only trained a predictor if the closest PDZ domain has ≥ 10 binding peptides (changing this threshold to nearby values does not affect our conclusions).

Generally, there are two strategies to build predictive models for peptide recognition domain-mediated interactions. A single-domain model is trained only on the interactions of an individual PDZ domain (one domain and its binding peptides) while a multi-domain model uses interaction data from multiple PDZ domains.

We tested our models using leave-one-PDZ-domain-out cross-validation, as domain sequence is important for performance. For the single-domain model, we trained on one single PDZ domain associated with all the interaction data, and tested for the held-out PDZ domain. For the multi-domain model, at each run, we trained the SemiSVR model on interaction data involving all PDZ domains but one, and then predicted the relative binding strength of all peptides interacting with the held-out PDZ domain.

2.3 Feature encoding

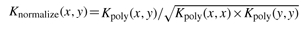

We represented a PDZ domain-peptide as a vector of descriptors including sparse vectors of either the full domain (118AA) or different definitions of the domain binding site (16 or 10AA) and the peptide ligand (10AA) and links between domain and peptide positions. Specifically, a PDZ domain = (P1, P2,…, Pn) and a peptide = (pep1, pep2,…, pepk), where Pi and pepj represent amino acids at a given position (i-th on the PDZ domain or j-th on the peptide)—in our case, n = 118 and k = 10. A PDZ domain–peptide pair is encoded as a tensor (outer) product between descriptor PDZ and peptide: PDZ*peptide = (P1pep1, P1pep2,…, P1pepk, P2pep1,…, Pnpepk). Since the inner product between two tensor product vectors (each one encoding one domain–peptide pair) can be rewritten as a product of two inner products (Jacob and Vert, 2008), we compute the inner product between vectors of any two PDZ domains or vectors of any two peptides. Furthermore, kernels on sequences can replace the inner product between the vectors of any two domains or any two peptides (the kernel trick), such as K(PDZ1*peptide1, PDZ2*peptide2) = K(PDZ1, PDZ2) × K(peptide1, peptide2). Thus, when sequences are used as the input for the kernels, one can rewrite the polynomial kernel as follows: Kpoly(x, y) = (Kbaseline(x, y)+1)p, where Kbaseline is simply the number of letters the input sequences (domain sequences or peptide sequences, respectively) have in common at the same positions. In practice, all kernels were normalized to 1 on the diagonal by  to make computation easier.

to make computation easier.

To encode the PDZ domain, we used the same alignment as published by Chen et al. (2008) since we want to compare our method to Chen's method using the same encoding (e.g. the same 16 binding sites). This alignment represents the conserved part of the domain containing all conserved secondary structure elements and the canonical binding site. See Supplementary Material for details and Supplementary Fig. S2 for the pairwise identity distribution of all pairs of 82 PDZ domain sequences based on this alignment. For the peptide, we use the entire length of 10 amino acids in all experiments.

There are many different feature encodings and kernels that could be used for our prediction task. We tried encoding PDZ domains using Profeat features (Li et al., 2006), which includes amino acid physicochemical properties, sequence pattern frequency and correlations; conventional sparse encoding where each position is represented as a vector of length 20 (one element for every amino acid type) has a one in the element corresponding to the amino acid at that position and the rest of the 19 elements are set to zeros, and then all vectors are concatenated; encoding peptides using 5 factors Atchley et al. (2005) and 11 factors (Liu et al., 2006), which are also based on amino acid physicochemical properties. We encoded the peptide using all above encodings, except for Profeat, for which the peptide sequence is too short. However, none of these encodings (Gaussian kernel) resulted in better performance than using the above described sequence-based encoding with a polynomial kernel (Supplementary Table S2).

3 RESULTS

Our goal is to predict binding strength of a previously unseen PDZ domain–peptide pair based on the primary sequence of the domain and peptide and quantitative interaction data. To address this, we applied regression analysis to published PDZ domain–peptide binding affinity data obtained using a combination of protein microarray and fluorescence polarization experiments (Chen et al., 2008; Stiffler et al., 2007).

3.1 Incorporating negative data for quantitative interaction prediction

3.1.1 Single domain models

Often, peptides that bind a PDZ domain will be modeled using a PWM, one per domain. The PWM method has been shown to capture binding energy (Stormo, 2000) and is often used for predicting PRM domain–peptide interactions (Tong et al., 2002; Tonikian et al., 2008). As a basic test of the modeling capability of the SemiSVR method and to compare it to the established PWM method (see Supplementary Materials), which was trained on quantitative data only, we trained it using positive quantitative and negative peptide data of an individual PDZ domain. We then tested the ability of each method to distinguish the stronger binding peptide among a pair of peptides randomly held out from the training peptide set (run for all possible peptide pairs, either two binders or a binder and a non-binder) and generated a percentage success rate for each of the 23 PDZ domains that bound at least 10 peptides. We found that the SemiSVR method performs better than the PWM method at the same task for the vast majority of PDZ domains (21/23, average performance of 0.79 versus 0.72, P-value = 0.0023, ranksum testing, Table 1). We had similar results when comparing to SVR (Table 1). Hence, incorporating negative data in regression analysis through SemiSVR improves quantitative prediction of interacting peptides, and even a simple application of the SemiSVR method given a set of peptides per domain is useful.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of single domain SemiSVR, SVR and PWM on 23 PDZ domains in leave two domain–peptide interactions out cross-validation testing

| PDZ domain | SemiSVR | SVR | PWM |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHAPSYN-110_2/3 | 0.75 | 0.57 | 0.71 |

| CHAPSYN-110_3/3 | 0.86 | 0.60 | 0.79 |

| GM1582_2/3 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.68 |

| HTRA3_1/1 | 0.73 | 0.66 | 0.70 |

| LIN7C_1/1 | 0.89 | 0.59 | 0.76 |

| MAGI-2_2/6 | 0.85 | 0.55 | 0.73 |

| MAGI-2_6/6 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.69 |

| MAGI-3_1/5 | 0.71 | 0.49 | 0.64 |

| MALS2_1/1 | 0.55 | 0.40 | 0.60 |

| OMP25_1/1 | 0.77 | 0.63 | 0.65 |

| PDZK3_1/1 | 0.78 | 0.64 | 0.70 |

| PDZ-RGS3_1/1 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.68 |

| PSD95_2/3 | 0.69 | 0.37 | 0.65 |

| PSD95_3/3 | 0.82 | 0.70 | 0.80 |

| PTP-BL_2/5 | 0.83 | 0.60 | 0.77 |

| SAP102_2/3 | 0.81 | 0.63 | 0.66 |

| SAP97_1/3 | 0.74 | 0.57 | 0.69 |

| SAP97_2/3 | 0.74 | 0.50 | 0.71 |

| SCRB1_3/4 | 0.84 | 0.59 | 0.75 |

| SHANK1_1/1 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.81 |

| SHANK3_1/1 | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.80 |

| G1-SYNTROPHIN_1/1 | 0.87 | 0.58 | 0.79 |

| ZO-1_1/3 | 0.75 | 0.51 | 0.75 |

| Average Performance | 0.79 | 0.61 | 0.72 |

Numbers indicate the average percentage of correct predictions. Bold numbers indicate the best performance.

3.1.2 Multi-domain model

We next trained the SemiSVR on interaction data of multiple PDZ domains to predict quantitative domain–peptide interactions involving previously unseen PDZ domains. We tested this using leave-one-PDZ-domain-out cross-validation, where we trained the SemiSVR model on interaction data involving all PDZ domains but one, and then predicted the relative binding strength of all peptides interacting with the held-out PDZ domain. To measure performance, we correlated the SemiSVR score with actual binding affinities using Pearson and Spearman's correlation coefficients. Since too few data points lead to inconclusive correlation results, we assessed the performance only for the 23 PDZ domains that bound to 10 or more peptides.

To enable the SemiSVR to learn from interaction data of multiple PDZ domains, the primary sequence of each PDZ domain and peptide in our training set was encoded as a feature vector (as compared with single domain testing where only peptides were encoded). We evaluated various ways of encoding these features (see Section 2 and Supplementary Table S2). For every PDZ domain–peptide interaction, we combined the feature vectors with the interaction binding affinity for regression analysis. We used a pairwise encoding with a polynomial kernel, which captures all pairs of amino acids between all domain and peptide positions, as this predictor performed best in initial experiments (see Section 2 and Supplementary Table S2). Input PDZ domain sequences were defined with 118 positions according to the PDZ domain multiple sequence alignment (Chen et al., 2008) and peptides were all of length 10AA.

For comparison, we trained an SVR model exactly as for the SemiSVR model, but only on quantitative positive data, while the SemiSVR was trained on both quantitative positive data and qualitative negative data. The SemiSVR performed better than SVR (Table 2), thus negative information is useful for regression and we used the multi-domain SemiSVR for further experiments. Closer inspection of the output score of SemiSVR and SVR indicates that both methods can predict relative, but not absolute, binding affinities (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Table 2.

Performance comparison of SemiSVR and SVR on 23 PDZ domains with associated peptides for Multi-domain model testing

| Performance measure | SemiSVR | SVR |

|---|---|---|

| Spearman's correlation | 0.605 | 0.501 |

| Pearson correlation | 0.653 | 0.574 |

Performance comparison based on leave-one-PDZ-domain out cross validation. A pairwise polynomial kernel (P = 2) using the whole PDZ (118AA) and whole peptide (10AA) as feature input was used for both predictors. Bold numbers indicate the best performance.

3.1.3 Comparison with a published method

We next tested if our new SemiSVR method performs better than the only published method for quantitative prediction of PDZ domain interactions applied to the same PDZ affinity dataset (Chen et al., 2008). This method uses input features that represent pairs of domain–peptide amino acids that spatially contact based on a PDZ domain–peptide structure. The contribution of each of the resulting 38 pairs to the interaction was learned from the affinity data (Chen et al., 2008). The published method was developed for both binary and quantitative prediction, but here we only compared SemiSVR to the quantitative version. We used leave-one-PDZ-domain-out cross-validation and Spearman's and Pearson correlation to measure performance of each method on the 23 PDZ domains that bound 10 or more peptides. The SemiSVR method performed better for the vast majority (20 of 23) of PDZ domains (Table 3). As a second test, we trained the SemiSVR model using the same ‘38 pairs’ input feature encoding developed by Chen. Again, the SemiSVR performed better in the majority of cases (18 of 23 PDZ domains; Table 3)—see Section 3.2 for an investigation into the domains that were poorly predicted. Thus, our SemiSVR is superior in method and input feature encoding compared with a previously published method.

Table 3.

Performance comparison of different prediction algorithms

| Performance measure | Spearman's correlation/Pearson correlation |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| PDZ domain | SemiSVR wholePDZ-118AA | SemiSVR 38 pairs | Chen |

| CHAPSYN-110_2/3 | 0.94/0.94 | 0.95/0.93 | 0.80/0.79 |

| CHAPSYN-110_3/3 | 0.89/0.88 | 0.60/0.57 | 0.59/0.50 |

| GM1582_2/3 | 0.65/0.58 | 0.41/0.35 | 0.36/0.19 |

| HTRA3_1/1 | 0.53/0.65 | 0.24/0.36 | 0.20/0.13 |

| LIN7C_1/1 | 0.61/0.68 | 0.47/0.56 | −0.37/−0.17 |

| MAGI-2_2/6 | 0.70/0.77 | 0.63/0.78 | 0.11/0.21 |

| MAGI-2_6/6 | 0.64/0.69 | 0.63/0.52 | 0.28/0.17 |

| MAGI-3_1/5 | 0.82/0.88 | 0.73/0.68 | 0.54/0.52 |

| MALS2_1/1 | 0.55/0.61 | 0.33/0.37 | 0.17/0.15 |

| OMP25_1/1 | 0.53/0.50 | 0.51/0.51 | 0.32/0.37 |

| PDZK3_1/1 | −0.20/0.04 | −0.13/0.02 | −0.22/0.02 |

| PDZ-RGS3_1/1 | 0.31/0.03 | −0.002/−0.05 | −0.08/0.07 |

| PSD95_2/3 | 0.97/0.92 | 0.82/0.87 | 0.53/0.66 |

| PSD95_3/3 | 0.75/0.88 | 0.597/0.68 | 0.22/0.17 |

| PTP-BL_2/5 | 0.36/0.40 | 0.34/0.53 | 0.18/0.16 |

| SAP102_2/3 | 0.97/0.94 | 0.91/0.92 | 0.91/0.94 |

| SAP97_1/3 | 0.34/0.76 | 0.46/0.63 | −0.16/0.14 |

| SAP97_2/3 | 0.95/0.95 | 0.91/0.92 | 0.77/0.85 |

| SCRB1_3/4 | 0.48/0.69 | 0.37/0.47 | 0.697/0.78 |

| SHANK1_1/1 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.51/0.44 | 0.95/0.96 |

| SHANK3_1/1 | 0.36/0.51 | 0.94/0.91 | 0.69/0.70 |

| G1-SYNTROPHIN_1/1 | 0.17/0.13 | 0.21/0.16 | 0.52/0.48 |

| ZO-1_1/3 | 0.64/0.65 | 0.61/0.64 | 0.26/0.16 |

| Average performance | 0.61/0.65 | 0.52/0.56 | 0.36/0.39 |

Performance comparison based on leave-one-PDZ-domain out cross-validation. Performance, measured by Spearman's and Pearson correlation coefficients for each domain are shown. The performance of SemiSVR with whole PDZ sequence (118AAs) and SemiSVR with 38 contacting residue position pairs and Chen's Backfitting method are listed in columns two to four. For the SemiSVR using 38 contacting residue position pairs as feature input, the linear kernel was used. The Chen method was run using the published implementation. All methods used all 10AA positions of the peptide. Bold numbers indicate the best performance for a given domain.

3.2 Performance determinants of quantitative prediction

To explore which aspects of our input features are most important for prediction performance, we trained a multi-domain SemiSVR model using subsets of PDZ domain sequences. We used 16 binding positions from the a1-syntrophin PDZ (a1synPDZ) structure described in Chen et al. (2008), and also 10 core binding positions derived from the intersection of all binding sites in nine available PDZ domain–peptide structures described in Tonikian et al. (2008). Using the whole PDZ sequence gave better overall performance, although the binding site encoding gives comparable performance (Supplementary Table S3), achieving Spearman's correlation of 0.605, 0.594, 0.594 and Pearson correlation of 0.653, 0.636, 0.649 for whole PDZ sequence, 16 binding positions and 10 core binding positions, respectively. This suggests that additional information is present in non-binding site positions that improves performance.

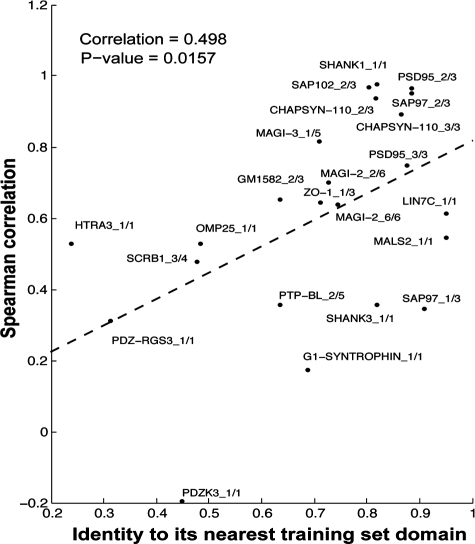

Next, we assessed the relationship between the predictor performance and percent sequence identity of the test PDZ to its nearest domain in the training set. We observed a positive correlation between performance and sequence identity (Fig. 2, Spearman's correlation, 0.498; P=0.0157). To further study this trend, we progressively removed all training PDZ domain interactions that are above a sequence similarity threshold to the test PDZ domain and retrained a SemiSVR model for each test domain (whole PDZ, pairwise polynomial kernel). We observed that the average SemiSVR performance decreased as the level of similarity of the test PDZ domain to the closest PDZ domain in the training set decreased (Supplementary Fig. S4). Hence, sequence similarity between a test PDZ domain and PDZ domains in the training set is a determinant of predictor performance.

Fig. 2.

Sequence similarity of a test PDZ domain to a training domain is an important performance determinant. PDZ domain similarity is defined by percent sequence identity and is calculated between each test PDZ domain to its nearest neighbor in the training set composed of 81 other PDZ domains. The prediction performance of the corresponding SemiSVR model is shown as Spearman's correlation.

3.3 A global approach improves the prediction performance

One potential advantage of our encoding framework approach is that we can incorporate interaction data of multiple PDZ domains (global) rather than just close neighbors (local) to improve prediction. To investigate this, we trained a set of ‘nearest neighbor’ SemiSVR predictors using only interaction data of the single domain with the highest sequence similarity to each test PDZ domain, ensuring that enough interaction data are used to create a viable predictor, and compared their performance to our multi-domain SemiSVR. In addition, since the SemiSVR's performance is correlated with the sequence similarity of a test PDZ domain to those in training data, we also assessed how the naïve usage of PWM based on the peptides of the nearest PDZ neighbor performs for quantitative interaction prediction.

We tested different ways to identify the nearest neighbor using whole PDZ, 16 and 10 position binding sites, and based on amino acid identity and scoring matrix BLOSUM62. Nearest neighbor SemiSVR performed better than the naïve PWM transfer method, presumably because negative interactions help with prediction. However, our multi-domain SemiSVR gave the best performance overall (Table 4). Thus, while sequence similarity is an important factor and nearest neighbors are important contributors to performance, our multi-domain SemiSVR uses additional information from across the PDZ domain family to improve performance.

Table 4.

Performance of our SemiSVR versus local information-based models using different PDZ domain similarity definitions

| Performance measurement | Spearman's correlation | Pearson correlation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SemiSVR | 118AA | 0.605 | 0.653 |

| Nearest neighbor SemiSVR | 118AA | 0.471 | 0.487 |

| Naïve PWM transfer (Identity) | 118AA | 0.303 | 0.323 |

| 16BSs | 0.305 | 0.319 | |

| 10BS | 0.326 | 0.303 | |

| Naïve PWM transfer (Blosum62) | 118AA | 0.305 | 0.311 |

| 16BSs | 0.296 | 0.274 | |

| 10BS | 0.354 | 0.286 | |

3.4 Validation of the method using blind PDZ domain–peptide affinity measurements

We next tested the SemiSVR model on newly measured PDZ domain–peptide interactions that were not used for training. The third PDZ domain of the human Scribble protein PDZ was cloned, expressed and purified and binding affinities to 57 peptides from natural human proteins were measured using fluorescence polarization (see Supplementary Material and Supplementary Table S4). Only the third PDZ domain was used because the other three had less than 45% sequence identity to the training set. This resulted in 36 binding peptides, enough for a confident performance assessment. The result shows that our SemiSVR method can accurately predict PDZ domain–peptide interactions (Spearman's correlation, 0.74, P = 8.85e-7). We found similar results testing our model on interactions involving domains in Fly and Worm data (Supplementary Table S5).

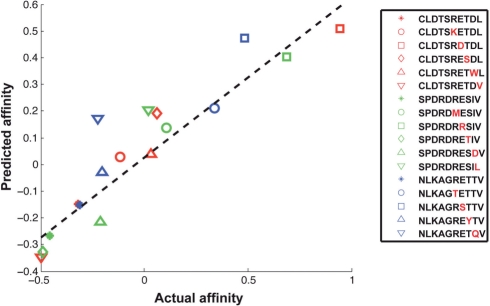

3.5 Predicting effect of peptide mutations

As another test of our SemiSVR method, we predicted the change in binding affinity of PDZ domain–peptide interactions resulting from amino acid changes in the peptide. We used a previously published dataset of PDZ–peptide affinities measured with fluorescence polarization (Chen et al., 2008) in which five single point mutations were introduced into each of three wild-type binding peptides (from proteins: Kv1.5, Nav1.5 and KIF1B) that bind the a1syn PDZ domain. The SemiSVR model successfully predicted the relative affinity change (increase or decrease versus wild type) for all mutants (i.e. 14/14 = 100%, one mutated KIF1B ligand had no measurable binding affinity). The correlations between the predicted and actual affinities of the mutated peptides for the SemiSVR are very high (Spearman's correlation, 0.921; P < 1e-16 and Pearson correlation 0.922; P = 1.414e-07) (Fig. 3). Therefore, our method can correctly predict the direction and relative magnitude of affinity changes in the mutant ligand compared with the wild type.

Fig. 3.

SemiSVR can predict changes in affinity resulting from point mutations introduced into known binding peptides of the a1syn PDZ domain. The three wild-type peptides are denoted by asterisks (*). Each mutant within a set is labeled by a different shape. Residue mutations are highlighted in red. One KIF1B mutant had no measurable binding, so it was excluded from our analysis. Performance of the SemiSVR on peptide mutation of a1synPDZ is very high (Spearman's correlation, 0.921, P < 1e-16 and Pearson correlation, 0.922, P = 1.414e−07). All affinities are scaled to the range [−1, 1] after taking log10.

3.6 Binary classification of PDZ domain–peptide interactions

Next, we assessed the performance of the multi-domain SemiSVR method on the presumably easier binary classification task—to predict whether a PDZ domain will bind a peptide or not. We performed leave-one-PDZ-domain-out cross-validation on the 23 PDZ domains with sufficient (>10) positive and negative peptides for the SemiSVR model and computed the average area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC AUC). The SemiSVR model was trained as before with all 81 non-test PDZ domains. The average ROC AUC score was 0.88 (Supplementary Fig. S5A).

To compare this result with that of a previous method for binary prediction published in Chen et al. (2008), we used their bootstrap testing approach. (i) PDZ bootstrap: leave 12% out for testing; (ii) peptide bootstrap: leave 8% out for testing; and (iii) both PDZ and peptide bootstrap. The SemiSVR performed well in this test (AUC of 0.862±0.016, 0.853±0.021 and 0.848±0.017, respectively, Supplementary Fig. S5B), which is comparable to the published performance of Chen's model [AUC: 0.91 (confidence interval (CI) 0.84–0.96), 0.84 (95% CI 0.76–0.89) and 0.87 (CI 0.67–0.98), respectively].

4 DISCUSSION

Inferring the relative strength of protein–peptide interactions mediated by peptide recognition modules (PRMs) will lead to better understanding of cellular processes. Here, we show that it is possible to predict affinity of PDZ domain–peptide interactions based on primary sequence information. We also show that incorporating both positive and negative interaction data using a novel SemiSVR approach improves prediction. This approach is also successful at predicting which PDZ domain–peptide pairs are likely to interact (binary prediction).

Based on the experimental data, a threshold of 100 μM separates quantitative ‘positive’ data from qualitative ‘negative’ data. Changing this threshold to more stringent values (i.e. 20 and 10 μM) did not change our results (Supplementary Table S6).

Although our method is mainly based on sequence similarity, it is interesting to analyze how much physicochemical factors contribute to our prediction performance. To investigate this, we assessed how well each of 11 properties from the ‘11-factor’ encoding (Liu et al., 2006) can be used individually for quantitative prediction of PDZ–peptide interactions using SemiSVR. We found that isoelectric point, hydrophilicity scale, polarity, average accessible surface area, van der Waals parameter epsilon and steric parameter are most important for performance, in decreasing order, suggesting they are the physicochemical factors that mostly modulate the binding strength of PDZ–peptide interactions (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Given that physical forces between the domain and the peptide 3D structures determine affinity, and our observation that SemiSVR performance correlates with sequence similarity between PDZ domains in testing and training sets, we postulate that natural PDZ domains with similar sequences have similar 3D structures that determine affinity in similar ways. This is supported by the observation that PDZ specificities are found conserved from worm to human (Tonikian et al., 2008). It has been shown that it is easy to mutate PDZ domains to bind non-natural ligands; however, we only see a limited set of PDZ domain specificities in nature (Ernst et al., 2009; Tonikian et al., 2008). These observations are consistent with a constrained model of PDZ specificity evolution where a set of initial PDZ domain specificities evolved, and that these were then expanded to form a finite number of subfamilies, each functionally similar down to the level of affinity determination. This model predicts that each subfamily has a characteristic structure and mode of determining binding affinity with a ligand. Regardless, we find that information useful for prediction is taken from the entire PDZ domain family and this improves prediction performance compared with using a naïve nearest neighbor-based predictor. As our method is trained on interaction data of natural PDZ domains, it may not do well at quantitative interaction prediction involving synthetic PDZ domains that have multiple mutations not found in our training data. We have noticed, in other work, that synthetic mutations may cause large changes in specificity, and presumably affinity (Ernst et al., 2009; Tonikian et al., 2008). This may occur by drastically changing the binding mode, for instance, by causing the peptide to rotate. We do not notice these types of large specificity changes arising from small sequence differences in natural PDZ domains, possibly because they disrupt normal PDZ function. The reduced predictive ability on synthetic PDZ domains, at least for specificity, has also been recently noticed (Smith and Kortemme, 2010). However, we were not able to test this due to lack of sufficient affinity data on synthetic PDZ domains.

We observed that some PDZ domains share identical subsequences in the 10 and 16 binding positions but bind the same peptides with different affinity. For example, both Dvl1 (1/1) and Dvl3 (1/1) share identical subsequences in their 16 binding positions yet bind to peptide Caspr4 with 79.298 μM and 30.756 μM Kd, respectively. Assuming the affinities are measured accurately suggests that additional sequence positions are modulating the binding strength of PDZ–peptide interactions. This is supported by previous work showing that sets of non-binding positions coupled with a binding site contribute to the binding energy (Lockless and Ranganathan, 1999). It has also been found that mutations in these sites may affect the structure of the binding site and thus alter binding affinity (Lockless and Ranganathan, 1999). Although our best predictor was obtained using the full PDZ sequence, the performance was only somewhat improved on average compared with using either 10 or 16 binding positions. This may be due to the limitation of our sequence-based approach that fails to capture structural features of PDZ domains and their ligands that are important for binding. Additional experimental data about how structural variation in the binding site combined with affinity data would be useful in the future to further address the importance of non-binding site positions on affinity.

The binding strength of domain–peptide interactions may also be affected by the presence of other partners bound. It will be interesting to examine the potential competition of PDZ binding sites bound by multiple PDZ domains expressed at different concentrations using our method. It will also be important to extend our method in the future to consider co-operativity (Gibson, 2009).

The performance of the SemiSVR depends on sequence similarity of test PDZ domains to those in the training set with sufficient binding peptides. The human Scribble PDZ domain we tested is fairly close to domains in the training set (94% similar), and thus is a good test of our approach. Because of this, we expect our method is immediately applicable to PDZ domains in multiple species that are close to the domains in our training set. We thus used our method to predict relative affinities for a set of reasonably close mouse and human PDZ domains (>60% domain sequence identity) to putative mouse and human PDZ ligands and included it as a convenient starting set (see Supplementary Tables S7 and S8), which is useful for prioritizing future experiments.

Our results highlight the need to collect experimental domain–peptide binding data covering PDZ sequence space to improve prediction methods. This means we need to measure affinities for domains that are less sequence related to those with known peptide affinities. We also need more affinity data from other species to make a more general conclusion about cross-species generality. Our future work will include incorporating more quantitative and qualitative interaction data from multiple sources into a prediction model to improve performance. For example, it might be possible to use phage display data to improve coverage and performance, which only includes qualitative positive PDZ domain–peptide pairs (Tonikian et al., 2008). Furthermore, quantitative prediction can potentially be improved by considering additional information about the domain and peptide, such as the 3D structure features of PDZ domains (Hue et al., 2010; Stein and Aloy, 2010; Beuming et al., 2009) and co-evolving residues (Halabi et al., 2009) in PDZ domain–peptide pairs. We plan to further develop our method along these lines and hope to increase its utility and accuracy in predicting quantitative interactions involving PDZ domains and apply it to other peptide recognition modules.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank D. Gfeller, S. Hui and L. Li for useful comments on the manuscript, R. Ammar and other Bader lab members for helpful suggestions and discussions and J.R. Chen for providing the backfitting algorithm code and the PDZ domain–peptide data.

Funding: X.S. is supported by a scholarship from the Chinese Scholarship Council. N.D. is supported by the key project of the National Nature Science Foundation of China (no. 10631070) and the National Nature Science Foundation of China (no. 10971223, 11071252). This project was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-84324).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Atchley WR, et al. Solving the protein sequence metric problem. Proc Natl Assoc Sci. USA. 2005;102:6395–6400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408677102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuming T, et al. High-energy water sites determine peptide binding affinity and specificity of PDZ domains. Protein Sci. 2009;18:1609–1619. doi: 10.1002/pro.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castagnoli L, et al. Selectivity and promiscuity in the interaction network mediated by protein recognition modules. FEBS Lett. 2004;567:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.03.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C-C, Lin C-J. LIBSVM: a library for support vector machines. 2001 Software available at http://www.csie.ntu.edu.tw/~cjlin/libsvm. [Google Scholar]

- Chechik G, et al. Activity motifs reveal principles of timing in transcriptional control of the yeast metabolic network. Nat. Biotechonol. 2008;26:1251–1259. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JR, et al. Predicting PDZ domain-peptide interactions from primary sequences. Nat. Biotechonol. 2008;26:1041–1045. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushing PR, et al. The relative binding affinities of PDZ partners for CFTR: a biochemical basis for efficient endocytic recycling. Biochemistry. 2008;47:10084–10098. doi: 10.1021/bi8003928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst A, et al. Rapid evolution of functional complexity in a domain family. Sci. Signal. 2009;2:ra50. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro E, et al. A novel structure-based encoding for machine-learning applied to the inference of SH3 domain specificity. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2333–2339. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson TJ. Cell regulation: determined to signal discrete cooperation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2009;34:471–482. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halabi N, et al. Protein sectors: evolutionary units of three-dimensional structure. Cell. 2009;138:774–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, et al. A map of WW domain family interactions. Proteomics. 2004;4:643–655. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, et al. Defining the specificity space of the human Src homology 2 domain. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2008;7:768–784. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700312-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hue M, et al. Large-scale prediction of protein-protein interactions from structures. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:144. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob L, Vert J-P. Efficient peptide-MHC-I binding prediction for alleles with few known binders. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:358–366. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RB, et al. A quantitative protein interaction network for the ErbB receptors using protein microarrays. Nature. 2006;439:168–174. doi: 10.1038/nature04177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgraf C, et al. Protein interaction networks by proteome peptide scanning. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew ED, et al. The precise sequence of FGF receptor autophosphorylation is kinetically driven and is disrupted by oncogenic mutations. Sci. Signal. 2009;2:ra6. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ZR, et al. PROFEAT: a web server for computing structural and physicochemical features of proteins and peptides from amino acid sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W32–W37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, et al. Quantitative prediction of mouse class I MHC peptide binding affinity using support vector machine regression (SVR) models. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:182. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockless SW, Ranganathan R. Evolutionarily conserved pathways of energetic connectivity in protein families. Science. 1999;286:295–299. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5438.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangasarian OL, et al. Knowledge-based kernel approximation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2004;5:1127–1141. [Google Scholar]

- Mangasarian OL, Wild EW. Nonlinear knowledge in kernel approximation. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2007;18:300–306. doi: 10.1109/TNN.2006.886354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M, et al. Quantitative predictions of peptide binding to any HLA-DR molecule of known sequence: NetMHCIIpan. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2008;4:e1000107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nourry C, et al. PDZ domain proteins: plug and play! Sci. STKE. 2003;2003:RE7. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.179.re7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson T, Nash P. Assembly of cell regulatory systems through protein interaction domains. Science. 2003;300:445–452. doi: 10.1126/science.1083653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez IE, et al. Genome-wide prediction of SH2 domain targets using structural information and the FoldX algorithm. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2008;4:e1000052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleinkofer K, et al. Comparative structural and energetic analysis of WW domain-peptide interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;344:865–881. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Kortemme T. Structure-based prediction of the peptide sequence space recognized by natural and synthetic PDZ domains. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;402:460–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smola AJ, Scholkopf B. A tutorial on support vector regression. Stat. Comput. 2004;14:199–222. [Google Scholar]

- Stein A, Aloy P. Novel peptide-mediated interactions derived from high-resolution 3-dimensional structures. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010;6:e1000789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiffler MA, et al. Uncovering quantitative protein interaction networks for mouse PDZ domains using protein microarrays. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:5913–5922. doi: 10.1021/ja060943h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiffler MA, et al. PDZ domain binding selectivity is optimized across the mouse proteome. Science. 2007;317:364–369. doi: 10.1126/science.1144592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormo GD. DNA binding sites: representation and discovery. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:16–23. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The International HapMap Consortium. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449:851–861. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong AH, et al. A combined experimental and computational strategy to define protein interaction networks for peptide recognition modules. Science. 2002;295:321–324. doi: 10.1126/science.1064987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonikian R, et al. A specificity map for the PDZ domain family. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonikian R, et al. Bayesian modeling of the yeast SH3 domain interactome predicts spatiotemporal dynamics of endocytosis proteins. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel C, et al. Structure, function and evolution of multidomain proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004;14:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunderlich Z, Mirny LA. Using genome-wide measurements for computational prediction of SH2-peptide interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4629–4641. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe MB, et al. A motif-based profile scanning approach for genome-wide prediction of signaling pathways. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:348–353. doi: 10.1038/86737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrinpar A, et al. Optimization of specificity in a cellular protein interaction network by negative selection. Nature. 2003;426:676–680. doi: 10.1038/nature02178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, et al. Pan-specific MHC class I predictors: a benchmark of HLA class I pan-specific prediction methods. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:83–89. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.