Abstract

Summary: Multiple templates can often be used to build more accurate homology models than models built from a single template. Here we introduce PconsM, an automated protocol that uses multiple templates to build protein models. PconsM has been among the top-performing methods in the recent CASP experiments and consistently perform better than the single template models used in Pcons.net. In particular for the easier targets with many alternative templates with a high degree of sequence identity, quality is readily improved with a few percentages over the highest ranked model built on a single template. PconsM is available as an additional pipeline within the Pcons.net protein structure prediction server.

Availability and implementation: PconsM is freely available from http://pcons.net/.

Contact: arne@bioinfo.se

1 INTRODUCTION

Accurate predictions of protein structures are important, as we will never have access to experimental structures for the vast majority of proteins. While high-quality experimental structures are extremely important, homology-modeling techniques are, widely applicable, much cheaper and can be applied on genomic scale.

A wide array of methods for protein structure prediction exists, both stand-alone software such as Modeller (Sali and Blundell, 1993) and Nest (Xiang, 2003), or available as web servers.

The performance of different methods is assessed biannually through the community-wide CASP experiment. Among other things, CASP has highlighted the importance of consensus-based approaches to the structure prediction problem. The oldest such method is Pcons (Lundstrom et al., 2001). The creation of Pcons was inspired by the successful consensus predictions made by the CAFASP team at CASP4. Pcons has been among the top-performing automated predictors since CASP5 and the top model quality assessment program in both CASP7 and 8 (Larsson et al., 2009; Wallner and Elofsson, 2007). The Pcons method is available as a web server (Wallner et al., 2007) at http://pcons.net/, where users can upload their protein sequences and obtain consensus predictions.

One limitation in Pcons.net is that it is based on single template models, while it is well accepted that the use of multiple templates readily can improve the quality of models (Larsson et al., 2008). However, one problem when using multiple templates is that sometimes the different alignments contain contradictory information, which results in convergence problems.

Here, we show that PconsM on average improve the models with a few percentage points within the popular Pcons.net protein modeling web server. The benefits of PconsM are several. Primarily, the qualities of the models appear on average to increase somewhat. Secondly, the use of multiple templates frequently leads to larger coverage of the target sequence, which means that less ‘free’ modeling is necessary. The throughput of Pcons.net [detailed in in Wallner et al. (2007)] is not affected by PconsM. An initial model is obtained within a few minutes and the final model is achieved within 24 h for the majority of targets.

2 THE PCONSM MULTIPLE TEMPLATES PIPELINE

At Pcons.net, an initial RPSBLAST (Altschul et al., 1997) search is performed to determine the ‘difficulty’ of the target sequence, as determined by the E-values returned by blast. The sequence is also submitted to a number of external servers such as HHpred (Soding, 2005) and SAM-T02 (Karplus et al., 2003); alignments are collected from a set of fold recognitions serves and models are built using Modeller. PconsM is implemented as a separate extension to this pipeline that is run when the internal and external predictions by Pcons.net are completed, and updated as soon as there are new alignments available. The input template sequences are ranked based on the quality score from Pcons.net for the corresponding single template models. From this ranking, multiple alignments with up to six template sequences are constructed using shell scripts. These are then used to build models as in our previous study, where in general model quality deteriorated with more than six templates (Larsson et al., 2008). In the last step, the quality of each of these six different models is assessed individually using the novel model quality assessment program ProQ2 (Ray et al., 2010; Wallner and Elofsson, 2003).

3 SUMMARY

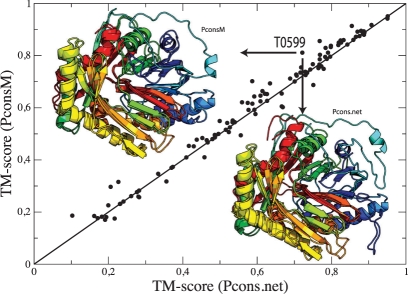

We benchmarked PconsM by assessing the increase in quality (TM-score) of these models over the baseline, consisting of the top-ranked, single-template models from Pcons.net.

In total, roughly 45% of the targets that a model created from multiple templates are better than the best single-template model. In some cases, the improvements are around 0.1 TM-units (Fig. 1). However, for the majority of targets the typical scale of improvement is around a few percentage points. The sum of TM-score showed a consistent increase over Pcons in both CASP8 and CASP9, see Table 1. The sum of TM-score for the highest ranking models is 58.9 and 65.5 for PconsM in CASP8 and 9, respectively, and 57.4 and 64.2 for Pcons.net.

Fig. 1.

CASP9 TM-scores for Pcons.net and PconsM, respectively, showing the per-target difference between the two methods. For the majority of targets, TM-score is increased with PconsM. For target T0599, highlighted in the figure, improvements can be seen in the central (blue) beta-sheet, and the loop sticking out in the Pcons model to the lower right is absent in the PconsM-model. TM-score is increased roughly to 0.1.

Table 1.

Sum of TM-score for the highest ranked models in CASP8 (using a subset of 90 comparable models) and CASP9 (108 targets released in November 2010)

| Method | CASP8 |

CASP9 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Easy | Hard | All | Easy | Hard | All | |

| PconsM | 50.1 | 8.8 | 58.9 | 56.3 | 9.2 | 65.5 |

| Pcons | 48.8 | 8.6 | 57.4 | 55.2 | 9.0 | 64.2 |

| HHpred | 46.4 | 6.9 | 53.3 | 54.0 | 6.7 | 60.7 |

| Fugue | 45.4 | 7.4 | 52.8 | 50.6 | 6.8 | 57.4 |

| SAM-T02 | 46.2 | 7.4 | 53.6 | 47.9 | 6.7 | 54.6 |

The results using the top ranking alignments from HHpred, Fugue and SAM-T02 were included as these were the highest performing single predictors used by Pcons.net. It should be noted that for some of the methods the predictions submitted to CASP were clearly better than the ones available locally for Pcons.net.

Multiple templates help to improve the quality of protein structures. Making a method available that can readily use multiple templates is of great importance, particularly since there is not an abundance of such methods available as web servers. The inclusion of multiple template models in Pcons.net means that the user will have a greater number of models to choose from when making the final decision about which model to use for further studies.

Funding: This work was supported by grants to A.E. from the Swedish Natural Sciences Research Council (VR-NT 2009-5072, VR-M 2007-3065); SSF (the Foundation for Strategic Research) (CBR grant). The EU 6'Th Framework Program is gratefully acknowledged for support to the Embrace project (Contract No: LSHG-CT-2004-512092). M.J.S. is funded by the EU FP7 Marie Curie Initial Training Network Transys (contract FP7-PEOPLE-2007-1-1-ITN). The EU 7'th Framework Program is gratefully acknowledged for support to the EDICT project (Contract No: FP7-HEALTH-F4-2007-201924).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Altschul S, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karplus K, et al. Combining local-structure, fold-recognition, and new fold methods for protein structure prediction. Proteins. 2003;53:491–496. doi: 10.1002/prot.10540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson P, et al. Using multiple templates to improve quality of homology models in automated homology modeling. Protein Sci. 2008;17:990–1002. doi: 10.1110/ps.073344908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson P, et al. Assessment of global and local model quality in CASP8 using Pcons and ProQ. Proteins. 2009;77:167–172. doi: 10.1002/prot.22476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundstrom J, et al. Pcons: a neural-network-based consensus predictor that improves fold recognition. Protein Sci. 2001;10:2354–2362. doi: 10.1110/ps.08501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray A, et al. Improved model quality assessment with proq2. 2010 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali A, Blundell T. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soding J. Protein homology detection by HMM-HMM comparison. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:951. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallner B, Elofsson A. Can correct protein models be identified? Protein Sci. 2003;12:1073–1086. doi: 10.1110/ps.0236803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallner B, Elofsson A. Prediction of global and local model quality in CASP7 using pcons and proq. Proteins. 2007;69(Suppl. 8):184–193. doi: 10.1002/prot.21774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallner B, et al. Pcons.net: protein structure prediction meta server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W369–W374. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang J. Jackal: a protein structure modeling package. 2003 [Google Scholar]