Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Lubiprostone, a prostaglandin E1 derivative, is reported to activate ClC-2 chloride channels located in the apical membranes of a number of transporting epithelia. Lack of functioning CFTR chloride channels in epithelia is responsible for the genetic disease cystic fibrosis, therefore, surrogate channels that can operate independently of CFTR are of interest. This study explores the target receptor(s) for lubiprostone in airway epithelium.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

All experiments were performed on the ventral tracheal epithelium of sheep. Epithelia were used to measure anion secretion from the apical surface as short circuit current or as fluid secretion from individual airway submucosal glands, using an optical method.

KEY RESULTS

The EP4 antagonists L-161982 and GW627368 inhibited short circuit current responses to lubiprostone, while EP1,2&3 receptor antagonists were without effect. Similarly, lubiprostone induced secretion in airway submucosal glands was inhibited by L-161982. L-161982 effectively competed with lubiprostone with a Kd value of 0.058 µM, close to its value for binding to human EP4 receptors (0.024 µM). The selective EP4 agonist L-902688 and lubiprostone behaved similarly with respect to EP4 receptor antagonists. Results of experiments with H89, a protein kinase A inhibitor, were consistent with lubiprostone acting through a Gs-protein coupled EP4 receptor/cAMP cascade.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Lubiprostone-induced short-circuit currents and submucosal gland secretions were inhibited by selective EP4 receptor antagonists. The results suggest EP4 receptor activation by lubiprostone triggers cAMP production necessary for CFTR activation and the secretory responses, a possibility precluded in CF tissues.

Keywords: airway anion secretion, airway submucosal glands, selective EP4 agonists and antagonists, CFTR, ClC-2 chloride channels

Introduction

Lubiprostone, a bicyclic fatty acid prostaglandin E1 derivative, was introduced into clinical medicine as a novel treatment for chronic idiopathic constipation and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) with constipation (Ueno et al., 2004). Given orally, it increased the bulk of secreted fluid in the intestine and colon sufficient to distend the gut and ease the passage of contents. At the molecular level, it was considered to act specifically on the chloride channels ClC-2 found on the apical surface of epithelial cells lining the gut, as indicated by studies using T84 monolayers (Cuppoletti et al., 2004). It seems the macroscopic mechanism for the anti-constipatory effect of the drug is correct; however, there is controversy about lubiprostone's actions at the molecular level. One implication of the proposed molecular mechanism is that anion-led electrogenic salt transport across the epithelia lining the gut can be stimulated independently of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) as the ClC-2 channel provides an alternative pathway for anion exit from the epithelial cells. If this were so then other epithelia bearing apical ClC-2 channels may also respond similarly, even if CFTR is absent or dysfunctional, as in cystic fibrosis (CF). Airway dysfunction is the major cause of morbidity and mortality in CF, due in the main to a paucity of airway surface liquid (ASL) caused by a failure of anion secretion in the surface epithelium and by the serous acini of the submucosal glands, together with an up regulation of absorptive processes in the surface epithelia. Expression of ClC-2 channels in HEK cells was used to show their sensitivity to lubiprostone (Cuppoletti et al., 2004), a sensitivity that disappeared when the siRNA for ClC-2 channels was simultaneously expressed (Cuppoletti et al., 2008). Thus, there is little doubt that lubiprostone is able to activate ClC-2 channels. In amphibian epithelial A6 cells, lubiprostone activates ClC-2 channels at low lubiprostone concentrations, but at higher concentrations directly activates CFTR, but without involving adenylate cyclase or the generation of cAMP (Bao et al., 2008). Yet other studies showed that prostaglandin EP4 receptors are the target for lubiprostone in epithelial tissues of the gut, activation leading to cAMP generation and CFTR activation (Bijvelds et al., 2009), but these findings were not confirmed when investigated using the same approach in a different species (Fei et al., 2009). Lipecka et al. (2002) used imunoblotting to discover the distribution of ClC-2 channels in the airways and concluded ‘The distribution of ClC-2 in airways is consistent with participation of ClC-2 channels in Cl- secretion’.

Recently, it was shown, using tracheal airway epithelia from sheep, pigs and humans, that all these epithelia responded to lubiprostone (Joo et al., 2009). Lubiprostone is extremely potent and, when applied apically to sheep trachea, has a Kd of 10.5 nM and a Hill slope of 1.08. The maximally effective concentration is c. 200 nM. The prostone increased anion secretion from both the surface epithelium and the airway submucosal glands. A few samples of human CF tracheal epithelia were also examined, which showed very low, non-significant levels of secretion to lubiprostone. No definitive conclusion about the target for lubiprostone was reached, as different aspects of the data supported different interpretations. For example, responses to lubiprostone in airway epithelia were inhibited by cadmium ions and gland secretions were not prevented when tissues were pre-exposed to high concentrations of forskolin, both findings suggesting that a non-CFTR dependent target was involved. However, the opposite view is supported by the ability of the CFTR channel blocker, GlyH-101, to inhibit lubiprostone in the sheep and the poor responses to lubiprostone in human CF airway tissue. Nevertheless, in Calu-3 epithelial monolayers, derived from the serous cells of human airway submucosal glands, responses to lubiprostone were unaffected after CFTR had been permanently down-regulated by 95% using siRNA technology or by high concentrations of GlyH-101 (MacVinish et al., 2007). While the CF mouse is not a good model for the human condition, changes in nasal epithelial potential difference measurements with lubiprostone were considered to result from non-CFTR dependent respiratory epithelial chloride secretion, an effect that disappeared in ClC-2 knockout mice. (MacDonald et al., 2008).

In this study, the hypothesis that prostaglandin receptors, rather than ClC-2 channels, are the target for lubiprostone in airway tissues is examined. It is concluded that EP4 receptors in the sheep are a major target for lubiprostone leading to activation of the adenylate cyclase/cAMP cascade and consequent anion secretion from both the surface epithelium and airway submucosal glands.

Methods

Airway tissues

All the experiments reported here have been made with epithelia dissected from the tracheas of sheep, obtained from an abattoir, in cooled oxygenated Krebs-Henseleit solution (KHS; for composition see below) containing indomethacin, 3 µM, to prevent prostaglandin formation and were used immediately after collection. The initial procedure for either short circuit current (SCC) recording or for optical measurements was the same. Short lengths of trachea (3–4 cartilage rings) were opened along the dorsal groove, pinned upon a dissecting block and a small sheet of the ventral epithelium (approximately 1.5 cm2) dissected free.

Epithelia were mounted either in Ussing chambers (window area 0.64 cm2) or used to measure submucosal gland secretion. Preparations of epithelium were stretched as close as possible to their original size during mounting.

SCC recording

SCC recording was made using the following protocol. Non-polarizable voltage sensing electrodes were introduced into ports in each Ussing half-chamber as close as possible to the epithelial surfaces. Similar current-passing electrodes were introduced into ports in each half-chamber as far as possible from the tissue. Both sides of the tissues were bathed in 5 mL of KHS that was continuously warmed at 37°C and circulated using a gas lift of 95% O2–5% CO2. Once the transepithelial potential became steady, tissues were voltage-clamped at zero potential using a WPI Dual Voltage Clamp-1000 (World Precision Instruments, Stevenage, UK). Fluid resistance compensation was used throughout. SCCs were continuously recorded using an ADInstruments PowerLab/8SP (AD Instruments, Chalgrove, Oxon, UK) and displayed on screen and stored for later analysis.

Amiloride, 10 µM was added to the apical bathing solution in all experiments in which short-circuited sheep tracheal epithelia were used and remained present for the duration of the experiments. This effectively eliminates alterations in electrogenic sodium absorption from affecting currents. As indicated above, indomethacin, 3 µM, was present in all solutions to which the tissues were exposed. Therefore, SCC measurements were made against a background of residual anion secretion, namely electrogenic chloride/bicarbonate secretion (Joo et al., 2009).

Optical measurements

To measure secretion from individual submucosal glands, the optical method described previously was followed (Joo et al., 2001). Briefly, epithelia were mounted in a small chamber so that the basolateral side was bathed in KHS at 37°C while the apical surface, after cleaning and drying, was covered with a thin layer of water-saturated mineral oil. The chamber was superfused with 95% O2–5% CO2. Gland secretions formed spherical bubbles at the exits from each gland. Images of the surface were captured every few minutes and the digital images stored, and later analyzed to give secretion rates of individual glands, using Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Addition and removal of agents was only achievable by changing the solution bathing the basolateral side of the mucosa.

Solutions

KHS had the following composition (in mM): 117 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 KH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3 and 10 glucose. This solution had a pH of 7.4 after bubbling with 95% O2–5% CO2.

Data analysis

Data are shown as means ± s.e. mean. When statistical comparisons were made, a standard Student's t-test was used throughout. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Materials

Amiloride, H-89 and carbachol were obtained from Sigma (Gillingham, UK), GlyH-101 from Calbiochem and lubiprostone (Amitiza) was from Takeda Pharmaceuticals America (Lincolnshire, IL, USA). L-161982, and PGE2 were from Enzo Life Sciences (Exeter, UK), while AH6809, GW627368X and SC-19220 were from Cayman Chemicals (Cambridge, UK).

L-902688 was a kind gift from Merck Frosst Canada Ltd (Quebec, Canada). Poorly soluble drugs were dissolved at high concentration (20 mM), in either dimethyl sulphoxide or dimethyl formamide. The low concentrations of solvents to which tissues were exposed (max 0.1%) were without effect. The receptor and channel nomenclature used in the paper follows Alexander et al. (2009).

Results

Effects of selective EP4 antagonists on responses to lubiprostone

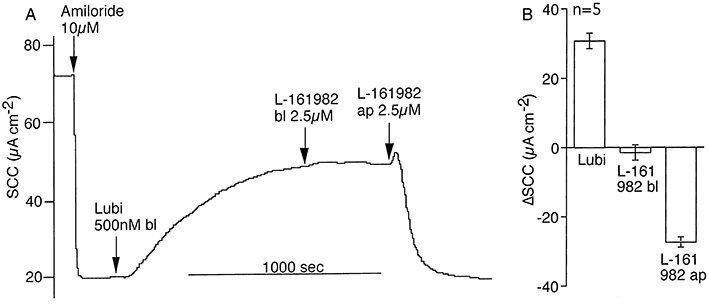

Initial experiments were designed to examine the sidedness of action of the selective EP4 antagonist, L-161982. L-161982, 0.5 µM caused about 80% inhibition of the response to a maximally effective concentration (200 nM) of lubiprostone, when both agents were added to the apical bathing solution. (Figure 1A,B). Responses to basolaterally applied lubiprostone were slow to reach maximal values. Basolaterally added L-161982 was without effect on the responses to lubiprostone, while apical addition of the antagonist caused a rapid reduction in current (Figure 2A,B). A typical response to basolateral application of lubiprostone, 500 nM, is shown in Figure 2A. Note that the response takes around 1000 s to reach steady state, slow when compared with the rapidity of the response to apical application (Figure 1A). Thus, while lubiprostone can reach its target(s) from either the apical or basolateral side of the tissue, the antagonist apparently can only gain access from the apical side.

Figure 1.

Effects of the EP4 receptor antagonist L-161982 on SCC responses to lubiprostone in sheep tracheal epithelium. Record showing response to lubiprostone, 200 nM, applied apically, after amiloride and before addition of L-161982, 0.5 µM, also applied apically (A). Cumulative data (B) show that responses to lubiprostone (lubi) were significantly reduced after L-161982 was added. Data are from seven preparations from four tracheas. The values of the plateau responses were measured at the moment the antagonist was added.

Figure 2.

Sidedness of action of lubiprostone and L-161982. (A) shows response to lubiprostone, 500 nM, applied basolaterally (bl) after amiloride and subsequent addition of L-161982, 2.5 µM, initially basolaterally and then apically (ap). Cumulative data from five identical experiments from two tracheas are given in (B).

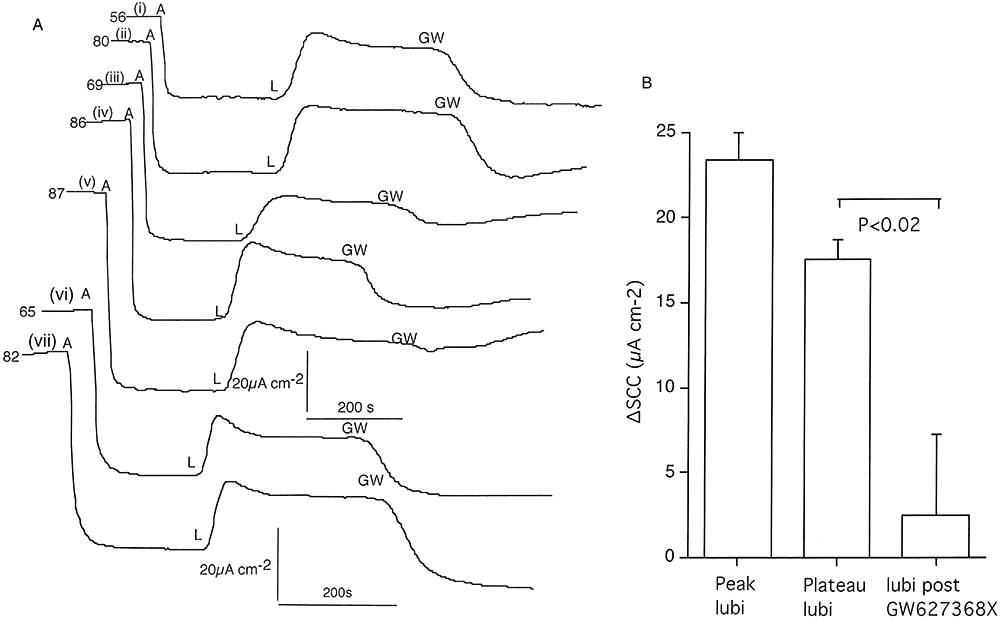

To further test the hypothesis that EP4 receptors are a target for lubiprostone a second EP4 receptor antagonist, namely GW627368X (Wilson et al., 2006) was investigated. The responses in seven epithelia to GW627368X, 10 µM, following 200 nM lubiprostone are shown in Figure 3A, both agents added apically. All seven responses are shown because of the considerable variability in response from no effect to complete inhibition and with some tissues showing various degrees of recovery after the antagonist. Overall, there was a significant inhibition of the lubiprostone response (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Effects of the EP4 receptor antagonist GW627368X on SCC responses to lubiprostone on tracheal epithelium (A). Responses to lubiprostone (L; 200 nM) applied apically after amiloride (A; 10 µM), are shown, followed by GW627368X (GW; 10 µM) also added apically. Plateau values are the SCC increases at the time the GW compound was added. Note the variation in response to the GW compound from no inhibition, incomplete inhibition to complete inhibition. The number at the beginning of each record gives the basal SSC (µA·cm−2) before amiloride (A) was added. Cumulative data from seven preparations from three sheep (i and ii) (iii, iv and v) and (vi and vii) are shown at the right (B).

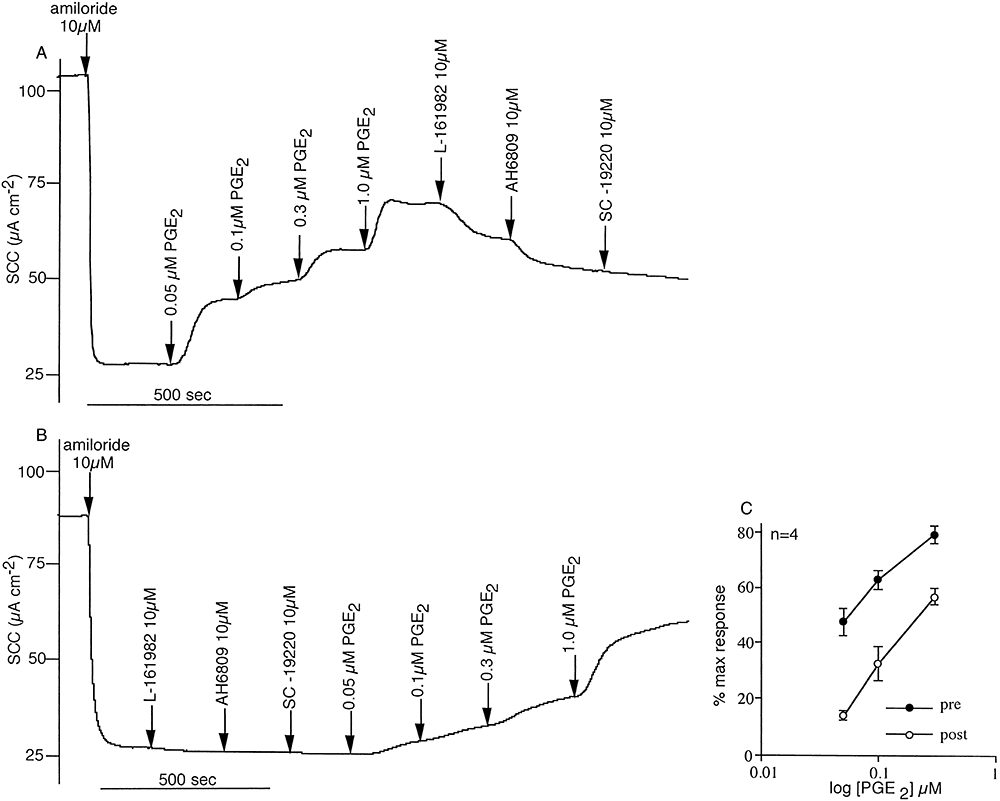

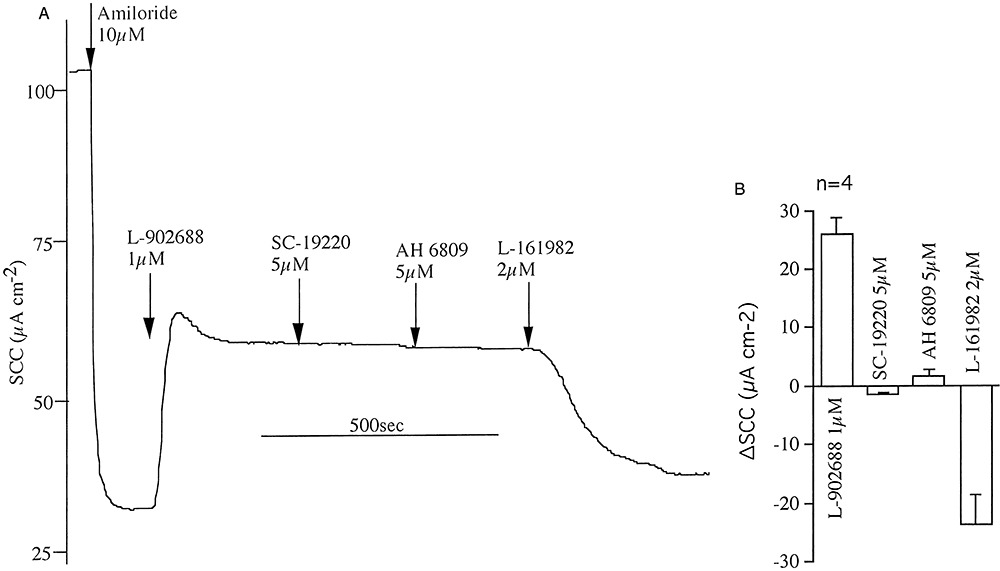

Other prostanoid receptor antagonists selective for EP1 receptors (SC-19220, 30 µM) (Rakovska and Milenov, 1984) and a non-selective antagonist that inhibits EP1,2&3 receptors (AH 6809, 30 µM) (Woodward et al., 1995) were investigated for their effects on the responses to lubiprostone (200 nM) when applied afterwards to the apical surface of short-circuited epithelia. Neither of these compounds had any effect on the SCC responses to lubiprostone (data not shown). Thus far the results support the hypothesis that lubiprostone specifically targets the EP4 receptor to the exclusion of EP1.2or3 receptors. It is, of course, necessary to show that the action of PGE2 on the EP4 receptor is linked to an increase in the transporting activity of isolated sheep tracheal epithelium and that its effects too are sensitive to L-161982. Figure 4A,B shows an example of a paired experiment in which EP receptor antagonists were added before or after obtaining partial concentration response curves to PGE2. Data from four paired experiments are provided in Figure 4C. Together they show that at least part of the SCC response to PGE2 is due to an effect on EP4 receptors since L-161982 alone partially inhibits the response. However, actions at one or more of the other EP receptors also contributed to the overall current increase. To focus more specifically on the EP4 receptor a specific EP4 agonist (Billot et al., 2003) was required. The EP4 selective agonist L-902688 was found to be maximally effective on SCC at around 1 µM, with a Kd of 85 ± 27 nM (n = 6) (data not shown). Figure 5A,B shows that neither SC-19220 nor AH 6809 had any significant effect on the agonist response, while L-161982 is an effective antagonist. Detailed information about prostanoid receptor antagonists can be found in Jones et al. (2009).

Figure 4.

Partial concentration response curves to PGE2 are shown in the presence and absence of prostanoid receptor antagonists and after amiloride inhibition of sodium absorption. In (A), the EP4 receptor antagonist L-161982, the mixed EP receptor antagonist AH6809 and the EP2 receptor antagonist SC-19220 were added in sequence after the plateau response to PGE2, 1 µM was achieved. In (B) the antagonists were added first. Both the experiments were repeated a further three times, but as SC-19220 produced no additional inhibition to that of L-161982 and AH6809 combined, only the former two were used (mean data given in C). All agents were added apically to the tracheal epithelia (four pairs from three sheep).

Figure 5.

Effects of prostanoid receptor antagonists on responses to the selective EP4 receptor agonist L-902688. The example shows the effects of addition of amiloride, followed by SC-19220 (EP2 receptor antagonist), AH 6809 (the non-selective EP1-3 receptor antagonist) and L-161982 on the SCC response to L-902688, all agents added apically (A). Data from five identical experiments are shown in (B).

Determining the affinity constant for L-161982 using lubiprostone and L-902688 as competing agonists

Concentration response curves to lubiprostone were determined by the cumulative addition of lubiprostone to the apical face of voltage-clamped tracheal epithelia in the absence or presence of a low concentration of L-161982 (Figure 6). Near parallel plots were obtained in which responses in the presence of the antagonist were moved to the right. The antagonism appeared to be surmountable. From mass action considerations the dose ratio (DR) is related to the antagonist concentration (A) by the equation (DR-1) =[A]Ki where Ki is the affinity constant of the antagonist. The two determinations of Ki represented in Figure 6C,D gave identical values for DR measured at the 50% response level, yielding a value of 17.1 × 106 M−1 for Ki (0.058 µM Kd) or alternatively pA2= 7.24.

Figure 6.

Concentration-response records to lubiprostone in two tracheal preparations in the absence (A) and presence of L-161982, 1 µM (B). Cumulative concentrations of lubiprostone were added until the maximal response was achieved. All agents, including amiloride, were added to the apical bathing solutions. Responses were converted to percentage of the maximal response and the data plotted on a semi-log scale (C). A second identical experiment gave similar data (D).

A further estimate for the affinity constant for L-161982 was made using a second agonist, namely the EP4 selective agonist, L-902688, as shown in Figure 7. Applying the same formulation as above the Ki value for L-161982 was 8.3 × 106M−1 (0.12 µM Kd) or alternatively pA2= 6.9.

Figure 7.

Concentration-response records to L-902688 in two tracheal preparations in the absence (A) and presence of L-161982, 1 µM (B). Cumulative concentrations of L-902688 were added until the maximal response was achieved. All agents, including amiloride, were added to the apical bathing solutions. Responses were converted to percentage of the maximal response and the data plotted on a semi-log scale (C). Note lack of effect of DMSO and change in SCC upon addition of L-161982.

A further example of the antagonism of L-902688 by L-161982 is given in Figure 8. These data are included as they illustrate potential inaccuracies affecting the determination of binding constants using the above method. After the control response curve had been obtained (Figure 8A), L-161982 2 µM was added to the apical side of the epithelium, resulting in the complete loss of agonist response. This implies that in the presence of L-161982, 2 µM no response to L-902688 will be seen until its concentration rises to above 1000 nM; clearly, that was not so (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

Concentration-response records to L-902688 in two tracheal preparations in the absence (A) and presence of L-161982, 2 µM (B). In (A) when the maximal response had been achieved L-161982, 2 µM was added. All agents, including amiloride, were added to the apical bathing solutions.

Also, the addition of L-161982 to the apical bathing solution after amiloride caused, in some instances, a small decrease in SSC (Figures 6,7). This was not an invariable finding (Figures 4,10). The mean change in SCC to L-161982 (1–10 µM) given after amiloride was −4.4 ± 1.1 µA·cm−2 (n = 16) and did not appear to be concentration-dependent or due to the solvent used. Thus, it cannot be known what fraction of the response to L-161982 in Figure 8A is due to the antagonism of L-902688 or due to its independent effect on SCC. The consequences of these findings on the determination of binding constants are discussed later.

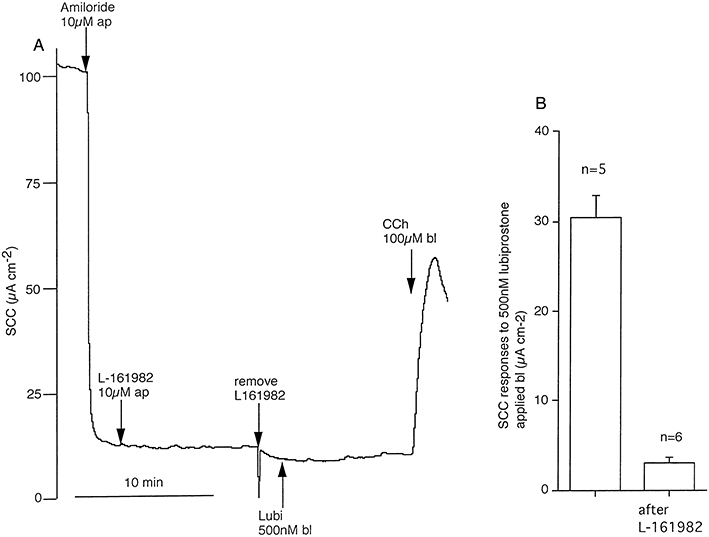

Figure 10.

Persistence of blockade of lubiprostone by L-161982 after its removal. In (A) amiloride, 10 µM and L-161982, 10 µM were added apically (ap) to a short circuited tracheal epithelium for 10 min, after which recording was halted and the apical solution replaced, now containing only amiloride. Subsequent addition of lubiprostone, 500 nM basolaterally (bl), gave only a small increase in current. Data from six experiments confirmed responses to basolaterally applied lubiprostone are significantly smaller after pre-exposure to L-161982 (B).

Evidence for involvement of adenylate cyclase in responses to lubiprostone

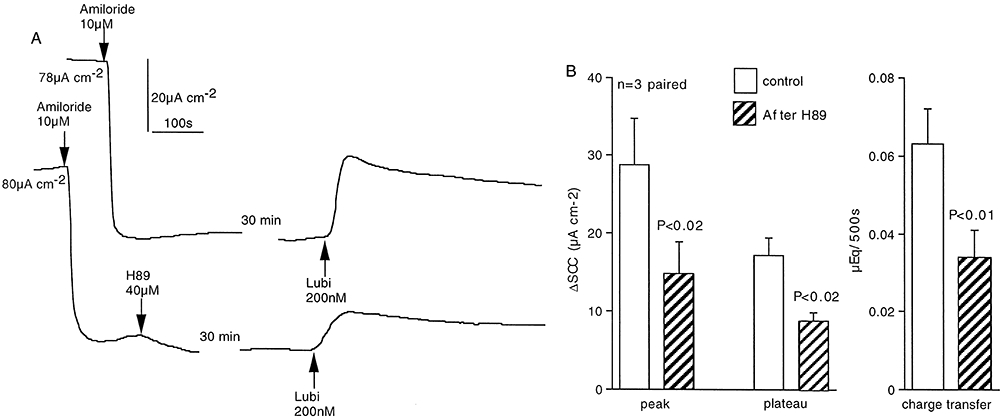

EP4 receptors are known to couple to Gs leading to cAMP generation and in turn to activation of protein kinase A (PKA) that, in turn, can phosphorylate essential sites on CFTR, resulting in channel opening (Sugimoto and Narumiya, 2007). To examine if this scenario was part of the lubiprostone-activated cascade, the PKA inhibitor H89 was used to examine if it affected responses to lubiprostone. One each of paired preparations was incubated with H89 for 30 min after the initial application of amiloride. Data from these experiments are presented in Figure 9A,B where it is shown that H89 significantly inhibited the response to lubiprostone, irrespective of whether the peak response, the plateau response or charge transfer over 500 s is taken as a measure of the response to lubiprostone. This suggests that the target for lubiprostone is coupled to the adenylate cyclase system.

Figure 9.

Effects of the protein kinase A inhibitor (H89) on responses to lubiprostone. One each of three matched pairs of epithelia from two sheep was exposed to H89 (40 µM, both sides) for 30 min. All tissues were then exposed to lubiprostone (200 nM ap) (A). The basal SCC, before amiloride was added is given at the beginning of each record. Peak and plateau responses, together with charge transfer during 500 s, were all significantly inhibited by about 50% in the presence of H89, using a paired t-test (B).

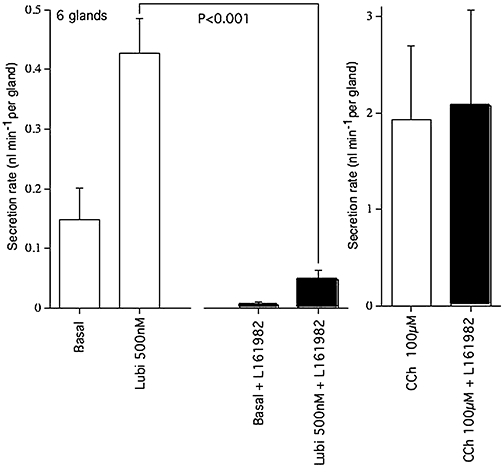

Are EP4 receptors involved in submucosal gland secretion due to lubiprostone?

Thus far, only SSC measurements have been used to obtain evidence about mechanisms of lubiprostone action. This technique basically measures electrogenic transport generated by the surface epithelium. However, secretion from submucosal glands is a major contributor to the formation of airway surface liquid. The secretion rate from submucosal glands cannot be measured electrically, but an optical method can be used where secretions from individual glands collect as small spheres of aqueous fluid (mucus) at the orifices of the glands when the apical surface is coated with a thin layer of oil. Measurement of the size of the spheres at intervals allows the secretion rate of individual glands to be calculated.

However, there are methodological problems that need to be overcome before the effect of EP4 receptor antagonists on lubiprostone responses can be investigated. These difficulties arise from the fact that the apical surface is not available for drug addition when gland secretions are being measured since it is covered with oil. This is not a problem with lubiprostone as it is clear that it can act from the basolateral face of the tissue, even though the response is slow in onset. However, the antagonist, L-161982, needs to be added apically to be effective (as shown earlier, Figure 2) Therefore, preliminary experiments, measuring SCC, were carried out to determine the persistence of the antagonist effect of L-161982 after removal. As shown in Figure 10A L-161982, 10 µM was added apically for 10 min after which recording was temporarily stopped, the apical solution was removed and replaced with fresh bathing solution containing only amiloride. This procedure virtually eliminated the response to lubiprostone, added basolaterally, however maintained tissue viability was demonstrated by the transient response to carbachol, added basolaterally. The general pattern indicated in Figure 10A is corroborated by the cumulative data given in Figure 10B.

Therefore, it appeared that if the epithelium was exposed to a high concentration of L-161982 before the apical surface was dried and covered with oil, the blocking effect on lubiprostone-induced gland secretion could be tested. Adjacent pieces of tracheal epithelium, one of which was pre-exposed to L-161982, 10 µM for 10 min prior to preparation for recording, gave the data shown in Figure 11. The secretion rates of six separate glands in each tissue were followed, both before and after lubiprostone was added basolaterally. Secretion rates are plotted as nl·min−1 per gland. Secretion rates in the presence of lubiprostone are significantly reduced following exposure to L-161982, indicating gland secretions in response to lubiprostone are similarly sensitive, as are SCC responses. Furthermore, basal secretion was virtually abolished in the presence of L-161982. Nevertheless, both treated and untreated tissues were able to respond to the non-CFTR dependent signal by basolateral exposure to carbachol. Measurements using exactly the same protocol with further paired pieces of tracheal epithelium gave similar results. Here, basal secretion was reduced from 0.18 ± 0.05 nl·min−1 per gland to zero by L-161982 exposure; and, after lubiprostone, the secretion rate of 0.39 ± 07 nl·min−1 per gland was reduced to 0.07 ± 0.02 nl·min−1 per gland (P < 0.002) in the presence of L-161982. All values were for groups of six glands. Thus, both secretion from submucosal glands and the surface epithelium appear to involve EP4 receptors. As a further check on this conclusion, it was expected that the EP4 agonist L-902688 would be active in causing secretion from submucosal glands. As with lubiprostone, L-902688 needed to be added from the basolateral side in these experiments, where it was less effective than with mucosal application. L-902688 (10 µM) increased the mean secretion from six glands from 0.26 ± 0.04 nl·min−1 per gland to 0.83 ± 0.13 nl·min−1 per gland (P < 0.002). The experiments in which glandular secretion is measured were the only ones in this study where amiloride was not present on the apical face of the epithelium. However, others have found no evidence for functional effects of ENaC channels in airway submucosal glands (Joo et al., 2006).

Figure 11.

Mean secretion rates of tracheal submucosal glands in response to lubiprostone in the presence and absence of L-161982. Mean rates of secretion (as nl·min−1 per gland) are given for 6 glands from both control and test tissues, measured during a basal period (15 min), following addition of lubiprostone (500 nM bl) (30 min) and following addition of carbachol (CCh, 100 µM bl) (15 min). Note that pre-exposure to L-161982 significantly reduces the basal, as well as the lubiprostone-induced, secretion rate, compared with controls.

Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to discover the nature of the receptor or receptors for lubiprostone that, when activated, produced secretion from either or both of the surface epithelium and submucosal glands of ovine airways. No clear answer to this question came from earlier studies, where some findings indicated secretion was independent of CFTR while others pointed to its involvement (see Introduction). The importance of the question relates to the lethal genetic disease CF, in which electrogenic secretion of anions, chloride and bicarbonate, is a crucial part of the process of maintaining healthy airways. In its absence, accumulation of mucus and bacterial infection supervene with a consequent loss of lung function. If lubiprostone could activate effective non-CFTR dependent mechanisms, it is possible that the genetic lesion could be bypassed.

Work with intestinal epithelia from wild type and CF mice and intestinal epithelia from CF patients and from controls produced evidence that in these tissues lubiprostone acted upon prostanoid receptors, specifically EP4 receptors (Bijvelds et al., 2009). Since EP4 receptors couple to Gs to mediate increases in cAMP concentration (Sugimoto and Narumiya, 2007) that can activate CFTR, it was concluded that lubiprostone-induced secretion was dependent on CFTR. However, another study with intestinal epithelia (ileum and colon) of guinea pig found that PG antagonists failed to inhibit lubiprostone induced secretion, neither were its effects blocked by the CFTR channel blocker CFTRinh-172 (Fei et al., 2009).

In the present study, the selective EP4 receptor antagonist L-161982 was a potent inhibitor of lubiprostone induced SCC increase, known to be due to increased anion secretion. High concentrations of other EP receptor antagonists that block EP1,2and3 receptors (AH 6809 and SC-19220) were without any effect on lubiprostone-induced SCC increases. Further, PGE2 activated chloride secretion in the trachea and part, at least, of the response was coupled to EP4 receptors as it too was sensitive to L-161982.

Further testing for the involvement of EP4 receptors was made with GW627368X (Wilson et al., 2006), another selective EP4 receptor antagonist. This too caused a significant inhibition of lubiprostone-induced SCC, often with some partial reversal of response with time, possibly due to its uptake into submucosal fat deposits.

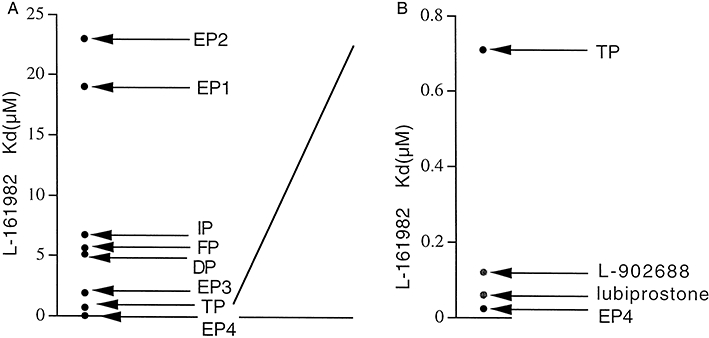

Perhaps the strongest evidence that lubiprostone targets EP4 receptors comes from measurement of the binding constant for L-161982 using lubiprostone as the competing agonist. Figure 12A shows the binding constants (Kd) for L-161982 from competitive binding experiments using HEK 293 cell membranes from cells expressing individual human prostanoid receptors (Machwate et al., 2001). In Figure 12B, part of the data are re-plotted on an expanded scale and include two additional values, namely those from the functional assays presented earlier in the results. Using either lubiprostone or the selective EP4 receptor agonist L-902688, the value of Kd for the antagonist was closer to the value for hEP4 receptors than to any other prostanoid receptor.

Figure 12.

Equilibrium binding constants (µM) for L-161982 with recombinant human prostanoid receptors (from Machwate et al., 2001) (A), plus values from functional studies using lubiprostone and L-902688 as agonists (B).

In assessing possible errors in binding constant measurements, it appeared that L-161982 was a more effective antagonist of L-902688 when it was applied after rather than before the agonist (Figure 8A,B), a discrepancy that was also noted with lubiprostone (data not shown). Not the whole of this difference is likely due to the small inhibitory effect on SCC sometimes shown by L-161982. A simple explanation is that, during the course of the experiment, the effective concentration of the antagonist falls slightly by partitioning, while this is not seen with acute administration. If this is so then the estimates of Kd for the antagonist may be even closer to those for hEP4 receptors, although there is no requirement that ovine and human values should be identical. Overall, the conclusion reached in this study is in general agreement with the findings of Bijvelds et al. (2009) on intestinal tissues. However, on occasions, they used very high concentrations of L-161982 (20 µM) that would have interfered with effects on other prostanoid receptors.

To discover whether EP4 receptors were also involved in gland secretion, a special methodology was required. While it was shown that lubiprostone could increase transport when added to the basolateral side of the epithelium, L-161982 was only effective when added apically. Therefore, pre-exposure to L-161982 was used before the surface was dried and covered with oil. This approach was justified by showing that the effects of basolaterally applied lubiprostone on SCC remained inhibited for some time after the antagonist was withdrawn. Adopting this protocol to the measurement of submucosal gland secretion, it was shown that secretion was inhibited by L-161982. Thus, the tentative conclusion is that both surface and glandular secretion by lubiprostone is mediated by EP4 receptors.

It is noted that both basal SCC and basal submucosal gland secretions can be reduced by L-161982. It is not known whether this is a direct effect of the antagonist or the antagonism of some unknown autacoid released by the tissue; the lack of concentration dependence perhaps favours the latter.

The sensitivity of the PGE2 induced current to AH6809 in the presence of a high concentration of L-161982 indicates more than one type of prostanoid receptor is coupled to ion transport stimulation in the airways, possibly EP2 as this receptor too is linked to cAMP generation (Sugimoto and Narumiya, 2007) (Figure 4). However, lubiprostone responses were unaffected by antagonists of EP1,2,and3 receptors, as were responses to the selective EP4 agonist L-902688 (Figure 5). These data strengthen the view that the actions of lubiprostone and L-902688 are confined in the airways to EP4 receptors, where activation leads to cAMP generation, a necessary trigger for CFTR activation of anion secretion. Evidence that the coupling of EP4 receptors to the adenylate cyclase-PKA cascade operates in the trachea is given by the effects of the protein kinase inhibitor H89, on responses to lubiprostone (Figure 9).

Many of the figures illustrating this report show that electrogenic, amiloride-sensitive, sodium absorption is the major component of the SCC in ovine trachea, while electrogenic anion secretion is a lesser component which can be increased by lubiprostone (Joo et al., 2009). In CF, the dysregulation of ENaC channels (Donaldson and Boucher, 2007) further emphasizes the discrepancy between these two processes. However, the balance between absorptive and secretory processes must be such, in healthy airways, as to maintain an adequate airway surface liquid (ASL) layer so that the mucociliary escalator can function. Without this, mucus accumulates and bacterial infection supervenes, leading eventually to a loss in lung function. It is argued that airway submucosal glands make a major contribution to the secretory process but are not involved in ENaC-dependent absorptive processes (Joo et al., 2006). Indeed, it has been shown that removal of the surface epithelium in porcine bronchi barely alters the overall secretion rate (Ballard et al., 1999). In this way, both the surface epithelium and the submucosal glands contribute to maintain the ASL layer at the correct level (Verkman et al., 2003). Thus, any compound that can cause a CFTR-independent chloride secretion from either or both of the surface epithelium or submucosal glands might be useful in CF. As shown here, the action of lubiprostone is apparently CFTR-dependent for its effects on both the surface epithelium and submucosal glands.

It is worth pausing to ask why the early literature considered ClC-2 channels as a major target for lubiprostone. In this laboratory, we found that Xenopus oocytes expressing hClC-2 responded to lubiprostone while water injected oocytes failed to respond (Cuthbert and Murthy, unpublished). Similar results were found with HEK-293 cells, and ClC-2 mRNA and protein were demonstrated in epithelial tissues (Cuppoletti et al., 2004). Further examples are given in the Introduction. If ClC-2 channels are involved in ion transport not only do they need to be present but also to be correctly located. For example, Catalan et al. (2004) found ClC-2 channels in colon epithelia but located basolaterally, and therefore, unable to support chloride secretion. In contrast, Bear and her colleagues (Gyomorey et al., 2000) described ClC-2 like channels in the ileal epithelium of CF knockout mice that could maintain a small chloride current of around 5 µA·cm−2. It was also shown that ClC-2 channels were located mainly at the tight junction complexes in the murine ileum, as was also shown for T84 monolayers (Cuppoletti et al., 2004) and for the porcine ileum and colon, where there is evidence that activation leads to an increase in transepithelial resistance (Blikslager et al., 2007). How this specific apical location for ClC-2 channels might affect transepithelial anion secretion is unknown. Unfortunately, there is no information about the presence or location of ClC-2 channels in ovine airways.

It has been argued that sheep airways are an excellent model for the human organs (Harris, 1997) and we have previously shown (Joo et al., 2009) that lubiprostone has similar activity on human trachea as in sheep. Assuming this similarity extends to actions of EP4 antagonists, then it will imply that lubiprostone's actions are CFTR-dependent in both species. In consequence, lubiprostone may find application in airway disease where airway surface liquid is deficient, as in various types of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, but it is unlikely to be useful in CF.

Acknowledgments

Support from the Cystic Fibrosis Trust is gratefully acknowledged.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AH 6809

6-isopropoxy-9-oxoxanthene-2-carboxylic acid

- ap

apical

- ASL

airway surface liquid

- bl

basolateral

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- GW627368X

((N-{2-[4-(4,49-diethoxy-1-oxo-1,3-dihydro-2H-benzo[f]isoindol-2-yl)phenyl]acetyl}benzene sulphonamide)

- KHS

Krebs-Henseleit solution

- L-161982

N-[[4'-[[3-butyl-1,5-dihydro-5-oxo-1-[2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-4H-1,2,4-triazol-4-yl]methyl][1,1'-biphenyl]-2yl]-3-methyl-2-thiophenecarboxamide

- L-902688

5R-[(1E)-4,4-difluoro-3R-hydroxy-4-phenylbut-1-en-1-1-yl]-1-[6-(1H-tetrazol-5-yl)hexyl]pyrrolidin-2-one

- SC-19220

1-acetyl-2-(8-chloro-10,11-dihydrodibenz[b,f][1,4]oxazepine-10-carbonyl)hydrazine

- SCC

short circuit current

Conflict of interest

None.

Supporting Information

Teaching Materials; Figs 1–12 as PowerPoint slide.

References

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to receptors and channels (GRAC) Br J Phamacol. 2009;158:S1–S254. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard ST, Trout L, Bebok Z, Sorscher EJ, Crews A. CFTR involvement in chloride, bicarbonate, and liquid secretion by airway submucosal glands. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:L694–L699. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.4.L694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao HF, Liu L, Self J, Duke BJ, Ueno R, Eaton DC. A synthetic prostone activates apical chloride channels in A6 epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 2008;295:G234–G251. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00366.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijvelds MJC, Bot AGM, Escher J, De Jonge HR. Activation of intestinal Cl- secretion by lubiprostone requires the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:976–985. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billot X, Chateauneuf A, Chauret N, Denis D, Greig GM, Mathieu M-C, et al. Discovery of a highly potent and selective agonist of the prostaglandin EP4 receptor. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:1129–1132. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blikslager AT, Moeser AJ, Gookin JL, Jones SL, Odle J. Restoration of barrier function in injured intestinal mucosa. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:545–564. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalan M, Niemeyer MI, Cid IP, Sepulveda FV. Basolateral ClC-2 chloride channels in surface colon epithelium: regulation by direct effect of intracellular chloride. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1104–1114. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuppoletti J, Malinowska DH, Tewari KP, Li Q-J, Sherry AM, Patchen ML, et al. SPI-0211 activates T84 cell chloride transport and recombinant human ClC-2 chloride currents. Am J Physiol. 2004;287:C1173–C1183. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00528.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuppoletti J, Malinowska DH, Tewari K, Chakrabati J, Ueno R. ClC-2 targeted siRNA inhibits lubiprostone activation of chloride currents in T84 cells. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(Suppl):A582,T1877. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson SH, Boucher RC. Sodium channels and cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2007;132:1631–1636. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei G, Wang Y-Z, Lui S, Hu H-Z, Wang G-D, Qu M-H, et al. Stimulation of mucosal secretion by lubiprostone (SPI-0211) in guinea pig small intestine and colon. Am J Physiol. 2009;296:G823–G832. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90447.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyomorey K, Yeger H, Ackerley C, Garami E, Bear CE. Expression of the chloride channel ClC-2 in the murine small intestine epithelium. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:C1787–C1794. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.6.C1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A. Towards an ovine model of cystic fibrosis. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:2191–2193. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.13.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RL, Giembycz MA, Woodward DF. Prostanoid receptor antagonist: development strategies and therapeutic applications. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:104–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo NS, Wu JV, Krouse ME, Senz Y, Wine JJ. An optical method for quantifying rates of mucus secretion from single submucosal glands. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:L458–L468. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.2.L458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo NS, Irokawa T, Robbins RC, Wine JJ. Hyposecretion, not hypoabsorbtion, is the basic defect of cystic fibrosis airway glands. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:7392–7398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512766200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo NS, Wine JJ, Cuthbert AW. Lubiprostone stimulates secretion from tracheal submucosal glands of sheep, pigs and humans. Am J Physiol. 2009;296:L811–L824. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90636.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipecka J, Bali M, Thomas A, Fanen P, Edelman A, Fritsch J. Distribution of ClC-2 chloride channels in rat and human epithelial tissues. Am J Physiol. 2002;282:C805–C816. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00291.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald KD, McKenzie KR, Henderson MJ, Hawkins CE, Vij N, Zeitlin PL. Lubiprostone activates non-CFTR-dependent respiratory epithelial chloride secretion in cystic fibrosis mice. Am J Physiol. 2008;295:L933–L940. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90221.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machwate M, Harada S, Leu CT, Seedor G, Labelle M, Gallant M, et al. Prostaglandin receptor EP4 mediates the bone anabolic effects of PGE2. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:36–41. doi: 10.1124/mol.60.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacVinish LJ, Cope G, Ropenga A, Cuthbert AW. Chloride transporting capability of Calu-3 epithelia following persistent knockdown of the cystic fibrosis conductance regulator, CFTR. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;150:1055–1065. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakovska A, Milenov K. Antagonistic effect of SC-19220 on the responses of guinea-pig gastric muscles to prostaglandins E1, E2 and F2α. Arch Int Pharmacodyn. 1984;268:59–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto Y, Narumiya S. Prostaglandin E receptors. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:11613–11617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno R, Osama H, Habe T, Engelke K, Patchen M. Oral SPI-0211 increases intestinal fluid secretion and chloride concentration without altering serum electrolyte levels. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(Suppl 2):A298. [Google Scholar]

- Verkman AS, Song Y, Thiagarajah JR. Role of airway surface liquid and submucosal glands in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:C2–C15. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00417.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RJ, Giblin GMP, Roomans S, Rhodes SA, Cartwright K-A, Shield VJ, et al. GW627368X ((N-{2-[4-(4,49-diethoxy-1-oxo-1,3-dihydro-2H-benzo[f]isoindol-2-yl)phenyl]acetyl}benzene sulphonamide): a novel potent and selective prostanoid EP4 receptor antagonist. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:326–339. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward DF, Pepperl DJ, Burkey TH, Regan JW. 6-Isopropoxy-9-oxoxanthene-2-carboxylic acid (AH 6809), a human EP2 receptor antagonist. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;50:1731–1733. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)02035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.