Abstract

“Convocation of Thanks” is the annual ceremony commemorating the gift of body donation to the Mayo Clinic Bequest program in the Department of Anatomy, College of Medicine, Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN. For 26 years, this ceremony of gratitude has given students, researchers, faculty, and family members an opportunity to reflect on the immeasurable value of these gifts. The authors describe the significance of ceremonies such as these in historical context and provide abridged transcripts of participants' speeches.

Dissection of the human body in the didactics of gross anatomy has been a cornerstone of medical education for centuries. Dissection was integrated into the medical curriculum in the 1800s and evolved from a public spectacle with the unethical procurement of cadavers to today's educational anatomical dissection with cadavers provided by bequest programs.1 Students are often abruptly immersed into the dissection experience with little preparation or reflection.2 They enter the gross anatomy laboratory eager to learn anatomy but often unsure of how to cope with the act of dissecting a human body.2,3 Anatomy faculty often encourage students to reflect on these issues during their extracurricular time, frequently using literature, theater, and art to explore aspects of professionalism and ethics.4,5 In outcome-based curricula, these activities contribute to student development and ideally contribute to the development of humanely oriented physicians.6 These learning activities are aligned with measurable graduate competencies7 and contribute to the development of the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of medical graduates.6,7 Even in these times of major changes in anatomy curricula with reduction of didactic contact hours,8 most gross anatomy courses dedicate a time to acknowledge the altruism of body donation, thereby encouraging students to reflect on death and dying.4,9

Anatomy memorial services allow students, donors, and their families to interact while recognizing common needs and boundaries.10 Students may develop a richer understanding of the last days of life that the donors experienced. Students' recognition and expression of gratitude for the sacrifices of donors and their families can enhance an emerging sense of professional responsibility. Students are given an opportunity to articulate what meaning they find in life and death and, in doing so, reflect on their own mortality. Such ceremonies provide positive and healing closure for students after the course in human dissection, which is intellectually and emotionally intense.10-12

In the United States, many anatomy programs have instituted formal services of gratitude to which families and friends of donors are invited.9,11-14 In some institutions, these services have expanded from small, informal services with only students and faculty offering reflections and readings in the gross anatomy laboratories15 into large memorial ceremonies that include the family members of donors and that feature music, refreshments, artistic slideshows, candelabras, and flowers decorating ballroom-sized halls.

At Yale University School of Medicine, medical and physician assistant students organize a “Service of Gratitude” for body donors and publish annually a compilation of the reflections expressed during the ceremony.14,16-20 Sparse descriptions of other memorials in the United States are available in older literature.11,13,15,21-23 Some articles include examples of students' songs and poems inspired by gross anatomy experiences.2,11,13,24,25 Other articles provide examples of student artwork, often in conjunction with an interweaving of humanities curricula into the gross anatomy course.2,25,26

In Japan, memorial services were held during the Edo period (1603-1868) for bodies of executed felons used for dissection for medical studies.27 The practice of holding annual gatherings in honor of body donors in Taiwan has nearly a 100-year history. Such ceremonies encourage and popularize the practice of body donation and express the respect for donors and their families.28,29 In Thailand, donated bodies are valued not as specimens for analysis, but as teachers. At the beginning of the laboratory dissection, students, faculty, family of the body donors, and Buddhist monks attend a dedication ceremony in the dissection laboratory in which donors are honored by having their names read aloud and by being awarded the title of “Great Teacher.” At the end of the course, another ritual is held, led by monks, and is more of a ceremonial procession during which each dissecting group carries their “teacher” to the site of final cremation.30,31 Ceremonies have also been reported from Europe,1,32-34 New Zealand,35 and Africa.4

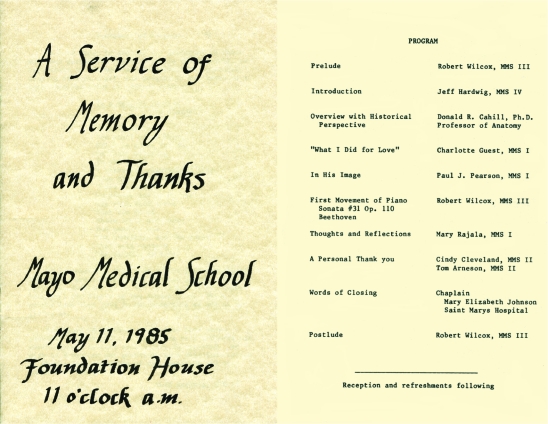

Each spring during the past 26 years, medical and physical therapy classes at the College of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, in true interprofessional fashion, have collaborated to express their gratitude to the families of body donors. Initiated by Dr Donald R. Cahill, the first Chairman of Anatomy at Mayo Clinic, and Dr James R. Carey from the Physical Therapy Program, the inaugural “Service of Memory and Thanks” was held on May 11, 1985, at Balfour Hall in the Foundation House, a former home of Dr William J. Mayo (Figure 1). About 40 families of donors attended this first convocation. In 1986, the ceremony was renamed the “Convocation of Thanks,” the name it still bears today.

FIGURE 1.

Cover page and the program page from the brochure of the first “Service of Memory and Thanks” organized in 1985.

Recently, the 26th “Convocation of Thanks” was held at Mayo Clinic and was attended by 350 guests, including members of donor families, all anatomy teaching faculty, and students of Mayo Medical School and the Physical Therapy Program (Figure 2). In this ceremony, members of both classes reflected publicly on their anatomy experience in poetry, music, dance, ballet, and artistic multimedia presentations.4,24,36,37 The “Convocation of Thanks” invites families of donors15 to honor their loved ones individually with the reading of their first names.38

FIGURE 2.

View of the screen and stage over Mayo Clinic “Convocation of Thanks” in Phillips Hall. The audience is faculty, students, and loved ones of the donors honored.

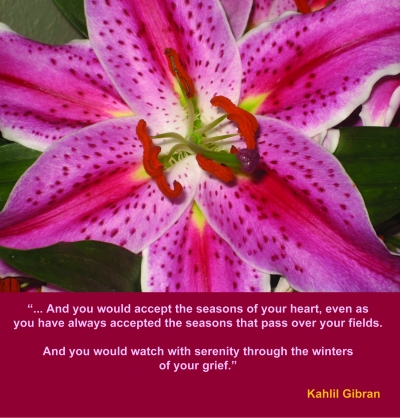

The themes and meditations are unique each year, but when planning ceremonies such as these, it can be helpful to study past programs and observe how speeches, musical selections, and artistic expressions have commonly been organized. For example, student photography of nature, flowers mainly, was presented in slideshow and in the printed program to metaphorically reinforce how the gift of body donation is akin to the perennial incarnation of flowers and seeds (Figure 3).39 Also, students distributed packets of flower seeds to all donor family guests along with white roses to symbolize that the blessings of many gifts, including grief, are not immediately evident, but reveal themselves over time; the gift triggers a metamorphosis that transforms the future, as planted seeds become flowers. To demonstrate how these themes were integrated into the 2010 ceremony, the authors have provided abbreviated transcripts of the speeches made at the 26th Mayo “Convocation of Thanks.”

FIGURE 3.

Excerpt from the student-designed program booklet. Poetry from Kahlil Gibran39 and the vibrancy of the image reflect the themes woven through the talks and ceremony. (Photograph courtesy of Ms. Amy Cole, a second year Mayo Medical School student.)

Jeffrey D. Strauss

“The Calling”

Your mothers, fathers, sisters and brothers, all knew you from the start

But their life and legacy did not end, as their time had come and they had to depart.

To another world is where they would make their stay

With one special stop along the way

They had one important gift, to us they would give

Not to move on, but through us they will live

Their talents, skills, an educating mind

Would teach us all, each and every time

The time we spent with them all, along the way

Has helped us become who we are here today

We learned from them and respect them all

For their thoughtfulness when they heard their call

So let's all be thankful, for even though they are gone,

Their wondrous gifts, they have forever passed on.

Shaun G. Heath

The donors' altruistic gift has touched the lives of many individuals. Henry Melvill, a nineteenth century English priest stated that “We cannot live only for ourselves. A thousand fibers connect us with our fellow men.” 40 This ideology is exemplified by the donors' ultimate contribution to humanity. Their gift revealed the complexity of the human body to medical school and health sciences students, developed the technical skills of future surgeons, enabled the study of researchers and enhanced the patient care methods of practicing physicians. Anatomical study and research enables clinicians to transform ideas into medical innovations and advancements. The profound impact of your loved one's generosity is perpetuated in the wisdom that will benefit future generations.

Through this noble gesture, the donors have bestowed far more than knowledge of human anatomy. They have shown what is not palpable. Their bequest expressed an absolute clarity and fortitude. Giving of oneself without return is the greatest act of selflessness. With unwavering faith your loved one has entrusted to us the most private and valuable mortal possession, their body, and we are humbled. Silently, the donors have taught by example the lessons not found in text—the most desirable virtues of humankind that instill integrity, build character and continually challenge us to ponder our own morality. We recognize the privilege of this opportunity and are deeply indebted.

We also acknowledge you, the families of the donors, for respecting the wishes of your loved one. Each one of you has sacrificed a sense of closure and perhaps compromised the funeral traditions of your family. In a time of loss, you recognized the significance of your loved one's contribution to medical education.

Kristin D. Zhao

The clear motivation of “the needs of the patient come first”41,42 helps us to focus our research endeavors on projects and investigations leading to new biomechanical discoveries that impact clinical care and help people like you and me, as well as people around the world.

I humbly thank you for the generous gift of your loved ones and for being a part of our team. Without your loved ones, none of these discoveries would have been possible.

Shawn Sahota

Anatomy was a rigorous course requiring great dedication and devotion. There was a significant amount of material, and very little time to commit details to memory. As an aspiring physician, it was an exciting course as it was the first time we were expected to think like doctors. And as a human being, it was an unusual experience because we were studying human structure from the bodies of people like us. I will refer to those individuals who donated themselves as teachers, because that is exactly what they were. Forgive me, but they were not cadavers or laboratory subjects; rather, they were teachers who helped mold our medical education.

Medicine is a unique subject. While there is significant learning from books and in the classroom, so much of a physician's training is accomplished through experience. I vividly recall the first few days. We started by discussing discretion and the importance of respecting the privacy of individuals who donated themselves. We spoke of respecting them and ensuring confidentiality.

I realize this morning's ceremony is inevitably difficult for many of you. To reminisce about the lives of loved ones lost can be trying. Yet, I hope this morning can also be a time that we celebrate the lives of your loved ones—celebrate their selfless nature and their devotion to others.

So in the spirit of celebration, I'd like to make a toast. Please hold up your white roses. To a good ceremony this morning, to having had this great experience in our medical school journey, and with best regards to our teachers who selflessly gave so we may learn.

Rachel R. Hammer

Each student has a symbolic token of our gratitude to give you: wildflower seeds. Why seeds? Well, with the arrival of spring every year, and especially on days like today, I am reminded of the poetic sacrifice symbolized in the flowers coming up around us. Having blossomed vibrant and full, splashing Earth with joy and color, isn't it inspiring that the last thing a flower does before it falls is to tenderly pass along its seeds? With the flesh of petals gently folding around their precious gift, we are humbled to receive such a legacy. There is hope in a seed. It isn't over when the petals fall away. We are reassured that when the darkness of winter passes, we will see them—their flesh, their color—again, in a bright season to come. We students are honored to have been entrusted with the responsibility to invest the seeds sacrificially given to us, and to use them as we cultivate our own gardens.43 It is said that all the flowers of tomorrow are in the seeds of yesterday.

Mary A. Feeley

We have come to the end of this “Convocation of Thanks,” this special time to remember our family members and friends and their generosity to our students. We have listened to their names. We remember with gratitude the gifts they shared both in life and beyond life. Their names are written on our hearts and they live on in our memory. It was Wynona Judd who sang “Every light begins with darkness; every flower was once a seed.”44 We celebrate darkness and light, seed and flower, and the wonder of both earth and sun.

Your loved ones have been partners as this group of students explored those basic questions of darkness and light. In those two symbols reside the deepest questions of human life: the questions of suffering, and sacrifice; the questions of the human spirit and its limits; the questions of despair and hope. These students have been invited by their partner to ponder their own mortality and their own generosity of spirit. In his or her death, your loved one has offered a glimpse into the wonder and power of the human spirit. Celebrating their memory is vital to our lives if they are to be lived with gratitude and a sense of daily miracles.

These physical therapy and medical students have probed what a textbook or a laboratory report might not offer and what is most difficult to teach: the skill of compassion, the art of care giving and respect, the wonder and beauty of something good and real that can grow out of suffering. We thank them for their partnership. And we thank these students and the faculty, staff and administrators who walk with them for the respect and dignity with which they met your loved one. They, too, have crossed a threshold into a new world which demands much of them.

Many of you have come to remember the faces and familiar gestures of those whose faces hang on the walls of your inner space. There they will always be with you. As you leave today, the students will give you the gift of wildflower seeds. Take them. Plant them. Nurture them. Bless them, and as winter and mounds of snow cover the landscape, trust them to the darkness, trust that next spring they will begin to reach for the sun and once again you will be surprised by the mysteries of darkness and light.

“See a blossom in your mind's eye. Allow it to fill the interior of your imagination.”45 And then slowly ascend the shaft toward wider light, turn your imagination around and around to see the blossom's many facets. Stored within is the memory of all flowers.

CONCLUSION

The lessons from the “Convocation of Thanks” continue to linger with the students whose hands touched and learned from the bodies, wrote tributes, played instruments, and gave the rose to honored guests. A woman whose husband donated his body to the program wrote the following in a letter to the student co-chairs after the “Convocation of Thanks:”

My husband was a medic in World War II. He was privileged to work with medical students and residents. He took great pride in that role. It was because of his background, and the opportunities to work with dedicated individuals like yourselves, that he made the decision to donate his body to medical education. Thank you for respecting him and for allowing him to be one of your many “teachers,” and remember, “the fragrance always remains in the hand that gives the rose.”46

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to acknowledge the past Chairman of the Department of Anatomy at Mayo Clinic, Dr. Stephen W. Carmichael, for his contribution to “Convocation of Thanks.” Authors are also grateful to all students and faculty who participated in the 26th Mayo Clinic “Convocation of Thanks.”

REFERENCES

- 1. Korf HW, Wicht H, Snipes RL, et al. The dissection course: necessary and indispensable for teaching anatomy to medical students. Ann Anat. 2008;190(1):16-22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Canby CA, Bush TA. Humanities in gross anatomy project: a novel humanistic learning tool at Des Moines University. Anat Sci Educ. 2010;3(2):94-96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hafferty FW. Cadaver stories and the emotional socialization of medical students. J Health Soc Behav. 1988;29(4):344-356 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lachman N, Pawlina W. Integrating professionalism in early medical education: the theory and application of reflective practice in the anatomy curriculum. Clin Anat. 2006;19(5):456-460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hammer RR, Jones TW, Nazer Hussain FT, et al. Students as resurrectionists—a multi-modal humanities project in anatomy putting ethics and professionalism in historical context. Anat Sci Educ. 2010;3(5):244-248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ousager J, Johannessen H. Humanities in undergraduate medical education: a literature review. Acad Med. 2010;85(6):988-998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gregory JK, Lachman N, Camp CL, Chen LP, Pawlina W. Restructuring a basic science course for core competencies: an example from anatomy teaching. Med Teach. 2009;31(9):855-861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Drake RL, McBride JM, Lachman N, Pawlina W. Medical education in the anatomical sciences: the winds of change continue to blow. Anat Sci Educ. 2009;2(6):253-259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pawlina W, Lachman N. Dissection in learning and teaching gross anatomy: rebuttal to McLachlan. Anat Rec B New Anat. 2004;281(1):9-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dixon KM. Death and remembrance: addressing the costs of learning anatomy through the memorialization of donors. J Clin Ethics. 1999;10(4):300-308 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weeks SE, Harris EE, Kinzey WG. Human gross anatomy: a crucial time to encourage respect and compassion in students. Clin Anat. 1995;8(1):69-79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Giegerich S. Body of Knowledge: One Semester of Gross Anatomy, the Gateway to Becoming a Doctor. 1st Ed. New York, NY: Scribner; 2002:1-272 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bertman SL, Marks SC., Jr The dissection experience as a laboratory for self-discovery about death and dying: another side of clinical anatomy. Clin Anat. 1989;2(2):103-113 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Morris K, Turell MB, Ahmed S, et al. The 2003 anatomy ceremony: a service of gratitude. Yale J Biol Med. 2003;75(5-6):323-329 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hull SK, Shea SL. A student-planned memorial service. Acad Med. 1998;73(5):577-578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rizzolo LJ. Human dissection: an approach to interweaving the traditional and humanistic goals of medical education. Anat Rec. 2002;269(6):242-248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim Y, Sandoval A. The 2005 anatomy ceremony: a service of gratitude. Yale J Biol Med. 2005;78(1):83-89 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Elansary M, Goldberg B, Qian T, Rizzolo LJ. The 2008 anatomy ceremony: essays. Yale J Biol Med. 2009;82(1):37-40 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yale University School of Medicine Students The 2007 anatomy ceremony: a service of gratitude; I: collected experiences. Yale J Biol Med. 2007;80(2):83-90 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eze O, Horgan F, Nguyen K, Sadeghpour M, Smith AL. The 2008 anatomy ceremony: voices, letter, poems. Yale J Biol Med. 2009;82(1):41-46 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nagy F. A model for a donated body program in a school of medicine. J Death Stud. 1985;9(3-4):245-251 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marks SC, Jr, Bertman SL, Penney JC. Human anatomy: A foundation for education about death and dying in medicine. Clin Anat. 1997;10(2):118-122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vora A. An anatomy memorial tribute: fostering a humanistic practice of medicine. J Palliat Med. 1998;1(2):117-122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Feinberg L. A memory. Clin Anat. 1988;1(4):297 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wagoner NE, Romero-O'Connell JM. Privileged learning. Anat Sci Educ. 2009;2(1):47-48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Paff M. Artist's statement: my cadaver. Acad Med. 2009;84(7):829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kozai T. Rituals for the dissected in pre-modern Japan. Nippon Ishigaku Zasshi. 2007;53(4):531-544 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kao T, Ha H. Anatomy cadaver ceremonies in Taiwan. Zhonghua Yi Shi Za Zhi. 1999;29(3):175-177 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lin SC, Hsu J, Fan VY. “Silent virtuous teachers”: anatomical dissection in Taiwan. BMJ. 2009;339:b5001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Winkelmann A, Güldner FH. Cadavers as teachers: the dissecting room experience in Thailand. BMJ. 2004;329(7480):1455-1457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Prakash, Prabhu LV, Rai R, D'Costa S, Jiji PJ, Singh G. Cadavers as teachers in medical education: knowledge is the ultimate gift of body donors. Singapore Med J. 2007;48(3):186-189 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tschernig T, Pabst R. Services of thanksgiving at the end of gross anatomy courses: a unique task for anatomists? Anat Rec. 2001;265(5):204-205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pabst VC, Pabst R. Danken und Gedenken am Ende des Präparierkurses. Dtsch Arztebl. 2006;103(45):A-3008 / B-2616 / C-2513 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kooloos JGM, Bolt S, van der Straaten J, Ruiter DJ. An altar in honor of the anatomical gift. Anat Sci Educ. 2010;3(6):323-325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McClea K. The bequest programme at the University of Otago: cadavers donated for clinical anatomy teaching. N Z Med J. 2008;121(1274):72-78 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cahill DR. To the editor. Clin Anat. 1988;1(4):297 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cahill DR, Dalley AF., II A course in gross anatomy, notes and comment. Clin Anat. 1990;3(3):227-236 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Druce M, Johnson MH. Human dissection and attitudes of preclinical students to death and bereavement. Clin Anat. 1994;7(1):42-49 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gibran K. The Collected Works. Everyman's Library. 1st Ed. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf; 2007:1–880 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Melvill H. Partaking in other men's sins. In: Melvill H. The Golden Lectures for the Years 1850 to 1855 Inclusive. Preached in St. Margaret's Church, Lothbury. 1st Ed. London, UK: James Paul; 1856;6 vols [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mayo WJ. The necessity of cooperation in medicine. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75(6):553-556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Viggiano TR, Pawlina W, Lindor KD, Olsen KD, Cortese DA. Putting the needs of the patient first: Mayo Clinic's core value, institutional culture, and professionalism covenant. Acad Med. 2007;82(11):1089-1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Voltaire PR, ed. The Complete Works of Voltaire: Candide v. 48. Oxford, UK: Voltaire Foundation; 1990:1-288 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Judd W. (Singer), Henry J Gordy E (Songwriters). When I Reach the Place I'm Going. In: Wynonna (audio CD). London, UK: Sony/ATV Music Publishing; 2004;3:44 min [Google Scholar]

- 45. Owen-Towle CS. On the threshold. First Unitarian Universalist (UU) Church of San Diego, San Diego, CA, Web site. http://scottishaire.blogspot.com/2010/06/on-other-side-of-door.html Accessed November 23, 2010

- 46. Attributed to Heda Bejar at Laura Moncur's Motivational Quotations. Quotation No. 1557 http://www.quotationspage.com/quote/1557.html Accessed January 7, 2011