Sometimes, people say something intending to tackle one problem and inadvertently make headway addressing another. A recent telling example is when Donald Rumsfeld, the then United States Secretary of Defense, spoke at a press conference in 2002 about the vagaries of finding weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. He said:

‘There are known knowns. These are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we now know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns. These are things we do not know we don't know.'1

He appeared to be talking off the cuff, but ever since he uttered the words, philosophers have been debating whether his language refers to some sort of deeper epistemological truth, a kind of new philosophy for the age. In other areas of life, serendipity appears everywhere: celebrated examples are Fleming's discovery of Penicillium notatum on an overnight petri dish,2 and Penzias and Wilson's accidental detection of the cosmic microwave background radiation from the noise emanating from their radiometer's antennae.3

Tony Blair has done something similar in his new autobiography Tony Blair: a journey.4 Most of the 718-page monolith is relatively easily disposed of: it is his version of events during his prime ministership, 1997–2007, a lot of which we knew. Yet in an intriguing way it is compulsory reading as it gets into the mind of a key decision-maker as he made the choices we agreed with or disputed, but regardless followed so closely. It is not nearly as self-serving, indulgent or religious as it could have been, or some have made out. That said, it has one section, buried in chapter 6, ‘Peace in Northern Ireland’, which may prove useful for improving the National Health Service (NHS) – or any large health organization.

Following Blair's account of the negotiations leading to the Good Friday Agreement by which the warring loyalist and republican parties, along with the British and Irish governments, came together to discuss the end of hostilities lies more than the germ of an idea about how to alter complex organizations. Blair presents 10 reasons why the agreement was successful, despite numerous setbacks and blind alleys. These principles are useful not only, as Blair intended, to be applied to other sticky political negotiations by those brokering peace among truculent, bellicose parties, but for longer-term cultural and organizational transformation. This type of change is badly needed in the NHS in substitution of, or as a replacement for, the structural change which is being sponsored by the Conservative–Liberal Democrat Coalition.5 Table 1 summarizes this proposal.

Table 1.

From the Good Friday Agreement to culture change in the NHS

| No | Blair's 10-point plan for negotiating among parties in Northern Ireland | General principles | These principles applied to NHS culture change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ‘At the heart of any conflict resolution must be a framework based on agreed principles.’ | First principles are the starting points; what are the ultimate rationale, and aim? | Articulate what we want in terms of NHS culture: a description of its nature and our future preferences for it are needed. |

| 2 | ‘Then to proceed to resolution, the thing needs to be gripped and focused on.’ | A long-term, dogged focus is needed. | Identify who is going to process the improvements across the years, and how, perhaps over a decade or more. |

| 3 | ‘In conflict resolution, small things can be big things.’ | If one or more of the parties think an issue is important, then it is important. | Key small-scale behaviours and practices, and attitudes and values, need to change, or else they can mushroom into major blockages. |

| 4 | ‘Be creative.’ | Various alternative and novel tactics and strategies should be tried. | Brainstorm novel solutions; compile a mix of initiatives that can be applied to the problem. |

| 5 | ‘The conflict won't be resolved by the parties if left to themselves.’ | Self-evidently, stakeholders within a system usually need help. | Clarify the external assistance needed, and the roles for the government, Department of Health, and internal and external agencies in enabling change. |

| 6 | ‘Realise that for both sides resolving the conflict is a journey, a process, not an event.’ | Historical traditions, ideologies and politics run deep and negotiations take time. | Determine the baggage that each NHS stakeholder carries; and devise ways to address or reduce this. |

| 7 | ‘The path to peace will be deliberately disrupted by those who believe the conflict must continue.’ | Be ready to be persistent in the face of truculent opponents and high risk. | Try to predict how and under what circumstances naysayers, perhaps medical, nursing, opposition, media or other groups, will try to derail the process, and circumvent these. |

| 8 | ‘Leaders matter.’ | The journey requires courage and quality decisions and direction. | Show clearly who is leading, and who is there to help: this is not just the Secretary of State for Health; leadership can come from many quarters. |

| 9 | ‘The external circumstances must militate in favour of, not against, peace.’ | Outside stakeholders and the prevailing environment are key variables. | Among external parties, such as HM Treasury, the public and private enterprise, show who can provide leverage for positive change. |

| 10 | ‘Never give up.’ | Do not accept defeat – keep addressing the problem with tenacity, longitudinally. | Long term is often too far away for governments myopically oriented to the short term; yet culture change is mostly long-term by nature. |

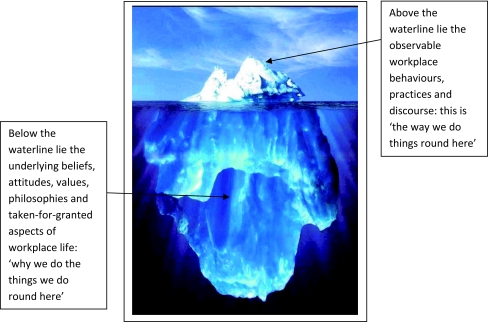

Culture change involves concerted effort, usually over lengthy periods, to influence and shape behaviours and practices on the one hand, and attitudes and values on the other. It is readily conceptualized as an iceberg, with the visible portion, the organizational and clinical activities, above the waterline, and the invisible collective mental constructs, below. The idea is that both need re-orientation to render cultural renewal ( Figure 1).

Figure 1.

An iceberg model of culture (in colour online)

Did Blair realize he had developed a yet-to-be tested but nevertheless promising new model for culture change across large complex systems? From a close reading of his book, it does not appear so. This is an unknown unknown: Blair did not say, and we are unable to confirm this. He looks to be genuine in his desire to leave recommendations for future political leaders who have to broker peace between antagonistic, heavily armed parties or in situations of civil confrontation. These are very important but do not happen very often in the UK. We are left with a potentially important model to contribute to health systems improvement, or plan for longer-term rejuvenation of other kinds of organizations.

So here's to Tony Blair's culture change model. Maybe the Coalition government can embark on a different journey of revitalization of the NHS than the one they have planned.6–9 This has much rhetoric about putting patients first and empowering staff, but proceeds to make mandatory a myriad of requirements, stipulations, demands, accountabilities, duties, obligations and timeframes for NHS progress, re-organizing it to within an inch of its life. It is hard imagine the new Government accepting this plea in reality, such is the political imperative to distance its policies from the past, but let us ask nevertheless. Dare the Coalition government put Blair's model to the test?

Footnotes

DECLARATIONS —

Competing interests None declared

Funding This research was supported in part under Australian Research Council's Discovery Projects funding scheme (project number 0986493)

Ethical approval Not applicable

Guarantor JB

Contributorship JB is the sole contributor

Acknowledgements

None

References

- 1.United States Department of Defense DoD News Briefing – Secretary Rumsfeld and General Myers. Washington, DC: United States Department of Defense; 2002. See http://www.defense.gov/transcripts/transcript.aspx?transcriptid=2636

- 2.Fleming A. On the antibacterial action of cultures of a penicillium, with special reference to their use in the isolation of B. influenzæ. Br J Experimental Pathology 1929;10:226–36 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Penzias AA, Wilson RW. A Measurement Of Excess Antenna Temperature At 4080 Mc/s. Astrophysical Journal 1965;142:419–21 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blair T. Tony Blair: A journey. London: Hutchinson; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walshe K. Reorganisation of the NHS in England. BMJ 2010;341:c3843; doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Secretary of State for Health Equity and excellence: Liberating the NHS. London: Department of Health; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Secretary of State for Health Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS. Analytic strategy for the White Paper and associated documents. London: Department of Health; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Secretary of State for Health Liberating the NHS: transparency in outcomes – a framework for the NHS. A consultation on proposals. London: Department of Health; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Health Liberating the NHS: Report of the arm's length bodies review. London: Department of Health; 2010 [Google Scholar]