Abstract

P granules, ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes specific to the cytoplasmic side of the nuclear pores of C. elegans germ cells, are implicated in post-transcriptional control of maternally-transcribed mRNAs. Here we show a relationship in C. elegans of Dicer, the riboendonuclease processing enzyme of the RNA interference and microRNA pathways, with GLH-1, a germline-specific RNA helicase and a constitutive component of P granules. Based on results from GST-pull-downs and immunoprecipitations, GLH-1 binds DCR-1 and this binding does not require RNA. Both GLH-1 protein and glh-1 mRNA levels are reduced in the dcr-1(ok247) null mutant background; conversely, a reduction of DCR-1 protein is observed in the glh-1(gk100) deletion strain. Thus, in the C. elegans germline, DCR-1 and GLH-1 are interdependent. In addition, evidence indicates DCR-1 protein levels, like those of GLH-1, are likely regulated by the Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), KGB-1. In adult germ cells, DCR-1 is found in uniformly-distributed, small puncta both throughout the cytoplasm and the nucleus, on the inner side of nuclear pores, and associated with P granules. In arrested oocytes, GLH-1 and DCR-1 re-localize to cytoplasmic and cortically-distributed RNP granules and are necessary to recruit other components to these complexes. We predict the GLH-1/DCR-1 complex may function in the transport, deposition, or regulation of maternally-transcribed mRNAs and their associated miRNAs.

Keywords: Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), KGB-1, Processing bodies, oocyte RNP granules, miRNA pathway

Introduction

Germ granules, ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) that are called P granules in C. elegans, are specific to the germ cells of most organisms. P granules were first described over twenty-five years ago, but their exact function remains unknown. P granules are cytoplasmic, non-membrane-bound, protein and RNA aggregates that exclusively associate with the nematode germline throughout the life of the worm (Strome and Wood, 1982; 1983). The location of P granules changes from a uniform cytoplasmic distribution in the newly-fertilized zygote to being perinuclear in P4, the primordial germ cell of the 16-cell embryo. P granules remain perinuclear during subsequent larval stages and throughout adult germline development until oocytes mature and P granules dissociate from the nuclear envelope (Strome and Wood, 1983). Almost all reported P-granule proteins, whether constitutive components or those in P granules specifically during early embryonic patterning, are known or predicted to have RNA binding functions; these include GLH-1-4, PGL-1-3, IFE-1, GLD-1, PIE-1, MEX-1, MEX-3, POS-1, OMA-1, the Sm proteins and CGH-1 (Roussell and Bennett, 1993; Gruidl et al., 1996; Kuznicki et al., 2000; Kawasaki et al., 1998; Kawasaki et al., 2004; Amiri et al, 2001, Jones et al., 1996; Mello et al., 1996; Guedes and Priess, 1997; Draper et al., 1996; Barbee et al., 2002; Shimada et al., 2006; Tabara et al., 1999; Navarro et al., 2001).

The Germline RNA Helicases (GLHs) are four constitutive components of C. elegans P granules. The GLH proteins contain glycine-rich, FGG repeats in their N termini (except GLH-3), multiple retroviral-like CCHC zinc fingers, and the eight conserved motifs characteristic of DEAD-box RNA helicases (Fig. 1A). Studies of the GLHs reveal that of the four family members, loss of GLH-1 is most critical (Kuznicki, et al., 2000; Spike et al., 2008) as GLH-1 is essential for proliferation of the germline. glh-1 knockdown by RNA interference (RNAi) affects P-granule structure (Kuznicki et al., 2000; Schisa et al., 2001); worms injected with double-stranded RNA specific for glh-1 and raised at the restrictive temperature of 26°C produce progeny with underproliferated germlines that lack oocytes and contain non-functional sperm (Kuznicki et al., 2000). glh-1 deletion mutants are also temperature-sensitive, sterile worms (Spike et al., 2008). Several mRNAs have been identified as P-granule components including pos-1, mex-1, mex-3, pie-1 and nos-2, each of which is important for patterning the C. elegans embryo suggesting that P granules regulate maternally-transcribed mRNAs (Tabara, 1999; Schisa et al., 2001; Subramaniam and Seydoux, 1999). GLH-1 is a homologue of Drosophila VASA that is known to be a translational activator (Hay et al., 1988; Lasko and Ashburner, 1988; Liu et al., 2009; Styhler et al., 1998; Tomancak et al., 1998).

Figure 1. GLH-1 interacts with DCR-1 and PGL-1.

A. A cartoon summarizing the interactions seen in Figs. 1B–C. B. Pull-downs out of wild type worm lysates with full length GLH-1 (lane 1), GST alone (lane 2), N-GLH-1 (lane 3), N*-GLH-1 (lane 4), C-GLH-1 (lane 5), full-length GLH-1, after adding RNase A (12 µg/µL for 20 min at room temperature) to the lysate prior to pull-down (lane 6), full-length GLH-1 without RNase A (lane 7), and 10% input lysate (lane 8). These pull-downs were tested with α-DCR-1 antibodies. C. Pull-downs out of wild type worm lysates with full length GLH-1 (lane 1), N-GLH-1 (lane 2), GST alone (lane 3), C-GLH-1 (lane 4), full-length GLH-1 after adding RNase A, as in Fig. 1B, to the lysate prior to pull-down (lane 5), full-length GLH-1 without RNase A, but treated as in lane 5, (lane 6), and 10% input lysate (lane 7). All GLH-1 proteins were GST-tagged except C-GLH-1, which was HIS-tagged. All lanes were tested by western blot with α-PGL-1 antibodies. The PGL-1 protein in lane 1 is no smaller than in other lanes; the gel edges ran slightly further. Western blots with α-GST and α-HIS antibodies show proteins were present in all lanes, Fig. S1.

Dicer, the RNaseIII riboendonuclease that processes non-coding RNAs in the RNAi and micro(mi)RNA pathways, is also important for germline maintenance and oocyte development. In mice, fruit flies, and nematodes, when Dicer is missing, the animals do not produce functional oocytes or offspring (Murchison et al., 2007; Megosh et al., 2006; Jin and Xie, 2007; Knight and Bass, 2001). In C. elegans there is a single Dicer gene, dcr-1. While the homozygous progeny of heterozygous dcr-1(ok247) mothers have normal-sized gonads, likely due to the rescuing effect of maternal DCR-1 protein during earlier stages of development, during the pachytene stage of oogenesis, germline development becomes disorganized and dcr-1 null mutants produce irregularly-shaped, non-functional endomitotic oocytes (Emo) (Knight and Bass, 2001). In contrast, loss of Dicer in mice or flies results in more severe phenotypes; neither mouse nor fly dcr-1 homozygous mutants reach adulthood.

In flies and mice, Dicer interacts with the conserved germline RNA helicase proteins VASA and MVH (Mouse Vasa Homologue) (Megosh et al., 2006; Kotaja et al., 2006). In Drosophila, there are two Dicer genes and proteins. VASA co-immunoprecipitates with Dicer-1, and depletion of Dicer-1 in fly embryos results in a dramatic decrease of VASA; however, VASA is unchanged in Dicer-2 depleted embryos suggesting the loss of VASA is associated with the Dicer-1-specific miRNA pathway (Megosh et al., 2006). In flies, Dicer-1 has not been reported as localizing to germ granules but rather is normally diffusely distributed throughout the cytoplasm of oocytes; however, when Maelstrom, a DNA binding protein and a putative miRNA pathway component, is missing, Dicer-1 localizes to discrete perinuclear granules that are likely germ granules (Findley et al., 2003). In mouse germ cells, Dicer co-immunoprecipitates with MVH, a protein essential for male germline development; this interaction requires the MVH C-terminus. Both Dicer and MVH localize to mouse chromatoid bodies, the equivalent of germ granules in mouse spermatids, along with other components of the miRNA pathway, including Argonautes (Ago2 and Ago3) and miRNAs (Kotaja et al., 2006). Before this work, the localization of DCR-1 in C. elegans had not been reported.

Because germ granules contain several components involved in the miRNA pathway, including Argonaute proteins and miRNAs as well as Dicer, others have hypothesized germ granules may function like the recently-described, somatic Processing (P) bodies (Kotaja et al., 2006; Nagamori and Sassone-Corsi, 2008; Strome and Lehmann, 2007; Wickens and Goldstrohm, 2003). P bodies are cytoplasmic, ribonucleoprotein (RNP) granules involved in mRNA degradation and storage that have been studied in a wide variety of organisms and somatic cell types, from yeast to mammalian cells (Ding et al., 2005; Jakymiw et al., 2005; Liu, et al., 2005a and 2005b; Sen and Blau, 2005; Anderson and Kedersha, 2006; Balagopal and Parker, 2009). P-body proteins are detected at high levels in the large cytoplasmic RNPs in C. elegans oocytes that form when ovulation arrests after hermaphrodites exhaust their limited numbers of sperm or after heat shock and other environmental stresses (Jud et al., 2007; Noble et al., 2008).

Here, we demonstrate that the C. elegans DCR-1 protein binds the P-granule component GLH-1. With a newly-generated α-Dicer antibody, we also report that DCR-1 localizes in close proximity to GLH-1 and to the nuclear pores of germ cells. GLH-1 and DCR-1 deletion strains reveal that reduction of either protein has a significant effect on the other, with both likely targeted for degradation by the Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), KGB-1. We report an essentially complete loss of GLH-1 protein and a nearly 3-fold decrease in glh-1 mRNA levels when DCR-1 is absent. Similarly, DCR is affected by loss of glh-1 at the protein level, with an almost 3-fold decrease in DCR-1 protein in glh-1(gk100) worms; however, dcr-1 mRNA levels are unchanged in the glh-1(gk100) strain. Both in glh-1 and dcr-1 mutants, P-granule organization is disrupted; we also report that in arrested oocytes GLH-1 and DCR-1 dramatically re-localize to large, cytoplasmic, P-body-like RNP granules, and these cortical granules are grossly affected by loss of either GLH-1 or DCR-1. In summary, the GLH-1/DCR-1 complex is required for the complete assembly of P granules, the constitutive, perinuclear, germline RNPs, as well as for assembly of the larger, cortical RNP granules that develop during oocyte arrest.

Methods and Materials

Strains

Worm strains used include: N2 (Bristol) as the wild type strain; PD8753 [dcr-1(ok247) III/ghT2[bli-4(e937) let-?(q782) qIs48] (I;III)]; NL687 [dcr-1(pk1351) III]; VC178 [glh-1(gk100) I]; KB3 [kgb-1(um3) IV] and CB4108 [fog-2(q71) V]. Nematodes were maintained on NGM plates at 20°C (Brenner, 1974), unless otherwise noted. The dcr-1(ok247), glh-1(gk100), kgb-1(um3) and fog-2(q71) homozygous mutants are referred to as dcr-1, glh-1, kgb-1 and fog-2 in this work. The C. elegans Knockout Consortium generated both dcr-1(ok247) and glh-1(gk100) deletion strains; the Bennett group generated the kgb-1(um3) deletion strain and the Priess group generated the GFP::MEX-3 transgenic line (Jud and Schisa, 2008).

Western Blot Analysis

When comparing protein levels of GLH-1 and DCR-1 between wild type and mutant worms, unless otherwise indicated, 50 adult worms were picked per lane for western blot analysis. Lysates were loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels, using 6% acrylamide for DCR-1 and GLH-4, with 8% for GLH-1 and the actin or tubulin loading controls; proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The GLH-1 rabbit antibody (Gruidl et al., 1996) was diluted to 1:1000. A DCR-1 rabbit antibody (Duchaine et al., 2006) was used at 1:750, while the DCR-1 rabbit antibody generated for this report was used at 1:3000. For loading controls, rabbit α-Actin (Abcam) or α-Tubulin (Sigma) antibodies were diluted 1:5000. The rabbit α-PGL-1 antibody was diluted 1:10,000. Goat α-rabbit or α-mouse HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Southern Biotech) were used at 1:10,000. Western blots were developed using Supersignal West Pico chemiluminescence (Pierce) and exposed to film. A LAS-4000 Fuji imager and MultiGauge software were used for quantification.

Pull-down Experiments

GST- and 6-HIS-tagged constructs cloned into the pFastBac vector (Invitrogen), were expressed by baculovirus in HighFive insect cells (Invitrogen) as described (Smith et al., 2002). Insect cell lysates and whole worm lysates, prepared from synchronized liquid cultures of adult worms, were collected and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Samples were thawed and diluted 1:1 in homogenization buffer (15mM Hepes pH 7.6, 10mM KCl, 1.5mM MgCl2, 0.1mM EDTA, 0.5mM EGTA, 44mM sucrose) plus one Complete© protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche) per 10 mL homogenization buffer and lysed by three passages through a French pressure-cell at 19,000 psi. Lysates were centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000g. 200 µL of insect lysate was added to 750 µL of worm lysate and rotated on a wheel for 1 hr at 4°C. The mixture was added to 50 µL of Glutathione-Uniflow Resin (BD Biosciences Clontech) and spun an additional 1 hr at 4°C. Beads were washed 4X in PBS containing 1% Triton®-X-100, proteins were eluted with 4X protein loading dye and analyzed by western blotting. All pull-downs and western blot analysis, with the exception of Fig. S3A, utilized the α-DCR-1 antibody that was the generous gift from the Mello laboratory, UMass.

Immunocytochemistry

N2, dcr-1, glh-1, kgb-1 and fog-2 adult worms grown at 20°C were splayed to extrude their gonads and quick-frozen on dry ice. For GLH-1 and PGL-1, gonads were fixed for 1 hr in 3% formaldehyde/0.1 M K2HPO4 pH 7.2 at room temperature, followed by 5 min in methanol at −20°C (Jones et al., 1996). For DCR-1, GLH-1, the nucleoporin proteins (mAB414, AbCam) and CGH-1, adult gonads were fixed for 1 min in methanol at −20°C, followed by 10 min in 3% formaldehyde at room temperature (Jud et al., 2008). For MEX-3, adult gonads were fixed for 5 min in methanol at −20°C, followed by 5 min in acetone at −20°C (Draper et al., 1996). Chicken α-GLH-1 antibody was used at 1:200, rabbit α-PGL-1 antibody at 1:3000, rabbit α-MEX-3 at 1:300, rabbit α-CGH-1 at 1:200, and mouse mAb414 at 1:100. For this report, α-DCR-1 antibodies were generated in rabbits with an N-terminal DCR-1-specific peptide, MVRVRADLQCFNPRDYQVEL conjugated to KLH (keyhole limpet hemocyanin). Sera were affinity purified using the SulfoLink Immobilization Kit for Peptides (Thermo Scientific) and eluted with high salt (2.5M KI); affinity-purified antibodies were diluted 1:10. All immunocytochemistry with DCR-1 used the antibody generated for this report. Fluorescent secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor, Molecular Probes) were diluted 1:400 or 1:3000. Some images were recorded with a Spot CCD camera on a Zeiss Axioplan microscope; others were taken on a Zeiss LSM 510 META NLO inverted confocal microscope at the MU Cytology Core or on an Olympus Fluoview FV300 or a Nikon A1R laser scanning confocal microscope at CMU. All confocal images shown are single sections that were analyzed using Adobe Photoshop. For heat shock, worms were kept at 34°C for 3 hrs prior to immunocytochemistry (Jud et al., 2008). To assess the effect of oocyte arrest on DCR-1 and GLH-1, fog-2 homozygous females were picked as L4s and grown for 1–2 days at 20°C; the unmated females were then fixed and stained. To isolate glh-1 and dcr-1 hermaphrodites depleted of sperm, L4-stage hermaphrodites were picked and cultured at 15°C. The adults were moved to new plates every 2 days, separating them from their progeny. When embryos were seen in the uterus (5–7 days post-L4), and ovulated oocytes were present on the plates, the hermaphrodites were considered “purged” of sperm.

Quantitative Real Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Wild type and glh-1 worms collected from twenty 60 mM plates were concentrated and frozen in 40 µl M9 and 10 µl 50× protease inhibitor (Roche). For isolating dcr-1 RNA, ~3500 homozygous (non-green) dcr-1 worms were individually picked and frozen. RNA was extracted from N2, glh-1 and dcr-1 strains using TRIZOL and RNeasy® Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s specifications. RNA concentrations were measured and equal amounts (1.0 µg) were reverse-transcribed using SuperScript® III RT (Invitrogen). 1.0 µl of these reactions was used for each quantitative real time PCR using the Maxima™ SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Fermentas) on a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Primers used are listed in Table S1. Cycling conditions were: 1X [10 min 95°C] and 40X [15 s 95°C, 1 min 60°C]. Relative expression levels were determined according to (Pfaffl, 2001), using the eft-2 transcript as a standard, with experiments performed in triplicate.

JNK Inhibitor Experiments

Young N2 adults, one day beyond the L4 stage, were grown in liquid culture at 20°C with 50 µM JNK inhibitor (SP600125, Calbiochem) or no inhibitor added. For example, inhibitor was added at the fifth hour for worms treated with inhibitor for one hour and at the beginning of the experiment for those exposed to inhibitor for six hours. All worms were grown a total of six hours and were analyzed for DCR-1 by western blot analysis.

dcr-1(RNAi)

dcr-1(RNAi) was performed to attempt to partially knockdown DCR-1 in the germline, producing worms with bulging vulvas, a trait of dcr-1 mutants (Knight and Bass, 2001), without causing the strong Emo phenotype that makes analysis of oocytes difficult. RNAi knockdown of dcr-1 mRNA was performed using Ahringer library bacteria (K12H4.8, III-4C08) engineered to produce dcr-1 dsRNA (Kamath and Ahringer, 2003) and seeded on plates containing 50 µg/ml carbenicillin and 1 mM IPTG. L1-stage, fog-2 worms were fed these bacteria at 24°C for ~24 hours, then males were removed, leaving L4-stage females, which were fed an additional 12–24 hours at 24°C. Similar to previous reports, variable phenotypic outcomes were observed following RNAi treatment of dcr-1, a gene involved in the mechanism of RNAi itself (Colaiácovo et al., 2002).

Results

DCR-1 interacts with the P-granule component GLH-1

We began by asking if the Caenorhabditis DCR-1 interacts with GLH-1 by pulling down proteins from wild type adult C. elegans lysates that interact with tagged GLH-1 and assaying for the presence of DCR-1 by western blot analysis. We conducted these pull-downs using several GST- and HIS-tagged GLH-1 constructs. The regions of GLH-1 illustrated in Fig. 1A were used in analyzing the pull-down products by western blots after determining that all tagged proteins were expressed (Fig. S1). Indeed, incubation of the full-length GST-GLH-1 with C. elegans lysate recognized DCR-1 suggesting these proteins interact (Fig. 1B, lane 1). To identify the regions of GLH-1 required for DCR-1 interaction, truncated GLH-1 constructs were tested, including N-GLH-1 that contains the first 315 amino acids of GLH-1, leaving the four zinc fingers intact, but lacking all eight helicase motifs. This protein did not recognize DCR-1 from worm lysates (Fig. 1B, lane 3), nor did a longer N*-terminal construct of 487 amino acids (Fig. 1B, lane 4). To determine if the C-terminus of GLH-1 interacts with DCR-1, we tested a 6-HIS-tagged GLH-1 construct that includes the eight helicase motifs, but lacks the first 315 amino acids of the N-terminus; this C-terminal protein did pull down DCR-1 (Fig. 1B, lane 5).

To determine if the physical interaction between DCR-1 and GLH-1 is RNA dependent, we first treated whole worm lysates with RNase A and then pulled down GLH-1-containing complexes using GST-GLH-1. The interaction of GLH-1 with DCR-1 remained intact despite RNase treatment, indicating the interaction is not RNA-dependent (Fig. 1B, lane 6). To verify the GST pull-down results, immunoprecipitations out of wild type lysates were performed with an α-GLH-1 antibody which pulled-down GLH-1-containing complexes and revealed that DCR-1 also co-immunoprecipitates with GLH-1 (Fig. S2)

The PGL-1/GLH-1 interaction differs from the DCR-1/GLH-1 interaction

To determine if members of the two constitutive P-granule families, GLH and PGL also interact, we also tested for the binding of GLH-1 and PGL-1 with similar GST and HIS pull-downs. PGL-1 was pulled-down with full-length GLH-1 (Fig. 1C, lane 1) but not with the control GST (Fig. 1C, lane 3). We also tested the N- and C-terminal GLH-1 constructs and found that PGL-1 interacts with GLH-1 through the GLH-1 N-terminus but not with the C-terminus (Fig. 1C, lanes 2 and 4).

We next asked if the interaction between GLH-1 and PGL-1 might require an RNA intermediate by adding RNase A to the lysates prior to immunoprecipitation. This resulted in the loss of the GLH-1/PGL-1 interaction (Fig. 1B, lane 5). These results indicate GLH-1 and PGL-1 interact in complex, with the interaction dependent on RNA. In addition, our GST pull-downs and immunoprecipitations do not pull down all P-granule components, as co-IPs with GLH-1 did not recognize PAR-1, PAR-3, MEX-1, or GLD-1 (data not shown) (Etemad-Moghadam et al., 1995; Guo and Kemphues, 1995; Guedes and Priess, 1997; Jones et al., 1996). However while the lysates used were from synchronized adults that contained embryos, since PAR-1, PAR-3, and MEX-1 are localized to P granules only during embryogenesis, their potential interactions with GLH-1 might not have been sufficiently robust to be detected without using an exclusively embryonic lysate. In summary, the DEAD-box motif region of GLH-1 interacts with DCR-1 while the GLH-1 region containing FGG repeats and zinc fingers interacts with PGL-1. In addition, the GLH-1/DCR-1 interaction does not depend upon an RNA intermediate, while the GLH-1/PGL-1 interaction does.

At the pachytene stage of oogenesis, DCR-1 is located in the cytoplasm, in nuclear puncta, and near the nuclear pores

Since GLH-1 and DCR-1 bind one another in a GLH-1/DCR-1 complex (Fig. 1B), we asked if these proteins co-localize in vivo. To date, no localization studies of DCR-1 have been reported in C. elegans, as existing antibodies did not recognize DCR-1 by immunocytochemistry. We generated and affinity purified a rabbit polyclonal antibody against an N-terminal peptide corresponding to the first 20 amino acids of DCR-1. Using wild type lysates, we found this antibody specifically recognizes a 210 kD protein, the size of the C. elegans DCR-1, by western blot analysis while no band was detected in dcr-1(ok247) mutant animals (Fig. S3A). By immunocytochemistry, DCR-1 was present throughout both the C. elegans germline and the somatic tissue (most easily seen in the extruded intestine) in wild-type worms, and again, no accumulation of protein was detected in the dcr-1 mutants (Fig. S3B).

To more closely examine the distribution of DCR-1 in the adult germline, immunofluorescent images of gonads extruded from wild type hermaphrodites were analyzed. The wild type germline is illustrated in Fig. 2A. Throughout the germline, DCR-1 was detected at low levels in uniformly-distributed small granules, more diffusely throughout the cytoplasm, and in some P granules (Figs. 2B; 3F). In the meiotic pachytene region, DCR-1 was also concentrated in distinct foci inside the nucleus that were sometimes adjacent to puncta stained by mAb414, an antibody that recognizes several nucleoporin proteins; however, the degree of co-localization was not high, with a Pearson’s coefficient of 0.26 (Fig. 2C, (insets) and merged images). To further examine DCR-1 in relation to GLH-1 and P granules, we labeled wild type adults and examined the pachytene region and oocytes with antibodies against DCR-1, GLH-1, and nuclear pore proteins (Figs. 2D–E; S4A–B). Around pachytene nuclei, DCR-1 occasionally co-localized with GLH-1 in P granules but did not have a high degree of co-localization with GLH-1; here the Pearson’s coefficient was 0.36. While the distribution of DCR-1 in germ cell nuclei included puncta on the inner face of nuclear pores, GLH-1 was almost exclusively perinuclear and highly enriched in P granules on the cytoplasmic side of nuclear pores (Figs. 2B, 2D–E, insets; S4A–B). The Pearson’s coefficient of 0.82 suggests a high degree of co-localization between GLH-1 and nuclear pores. Thus, although DCR-1 and GLH-1 do not appear to have a high degree of co-localization, the GLH-1/DCR-1 biochemical interaction may reflect a transient interaction at or near nuclear pores. While GLH-1 is highly enriched at nuclear pores, DCR-1 seems likely to traffic through the nuclear pores as it is detected both inside nuclei and in the cytoplasm. In maturing wild type oocytes, DCR-1 was also detected throughout the cytoplasm and nucleus, sometimes slightly enriched at plasma membranes (Figs. 2E; S4B; data not shown).

Figure 2. DCR-1 localizes in close proximity to nuclear pore complexes.

A. A schematic of the C. elegans gonad from an adult hermaphrodite containing the adult germline, adapted from Minasaki et al. (2009). In the distal gonad, the somatic distal tip cell directs mitotic germ cell proliferation; germ cells then transition into meiosis and enter pachytene. The distal region is a syncytium, while in the proximal gonad oocytes cellularize and mature before passing through the spermatheca where they are fertilized. B. DCR-1 (green) is localized throughout the adult gonad in a wild type hermaphrodite, both throughout the cytoplasm and in the P granules surrounding the germ cell nuclei. This image of a splayed gonad includes some distal and proximal regions surrounding the gonad bend. The same gonad is seen in the middle panel, showing the localization of GLH-1 (red). DCR-1 and GLH-1 appear to co-localize in the merged image (yellow). These images were taken with a Zeiss Axioplan microscope. Size markers=25 µm. C. Confocal micrographs of the pachytene region of a wild type hermaphrodite using mAb414 antibody (green), which recognizes the FG repeats of several nucleoporins (Davis and Blobel, 1986) and α-DCR-1 antibody (red). D. Immunocytochemistry in the pachytene region of a wild type hermaphrodite showing α-GLH-1 (red), α-DCR-1 (green) and mAb414 (blue) antibodies. E. Immunocytochemistry in a wild type oocyte showing α-GLH-1 (red), α-DCR-1 (green), and mAb414 (blue) antibodies. Arrows denote the region enlarged in each inset. Size markers=5 µm. To evaluate the extent of co-localization between pairs of proteins in co-staining experiments, Pearson’s Correlation was determined using Nikon NIS Elements software. Pearson’s Correlation is a commonly accepted means for describing the extent of overlap between image pairs and takes into account only the similarity of shapes between images but not the image intensity (Adler et al., 2010).

Figure 3. GLH-1 and DCR-1 are interdependent.

A. Western blot analysis of wild type versus dcr-1(ok247) protein lysates with α-GLH-1 antibody; tubulin is the loading control. B. Western blot analysis of wild type versus glh-1(gk100) protein lysates with α-DCR-1 antibody; actin is the loading control. The western blot in 3A used 50 worms per lane, while those in 3B used 500 worms per lane to compensate for the low levels (~10%) of truncated GLH-1 protein in the glh-1(gk100) strain. The use of different loading controls between the western blots in A and B was unintended, reflecting the availability of these control antibodies at the time. C. GLH-1 localizes to P granules in wild type (left); GLH-1 is not detected in a dcr-1(ok247) gonad (right) using α-GLH-1 (red), and DAPI-stained nuclei (blue). D. A wild type and a dcr-1(ok247) gonad reacted with α-PGL-1 antibody (green), and DAPI-stained nuclei (blue). Arrows indicate the distal gonad. The arrowhead points to two endomitotic oocytes (Emo). E. A glh-1(gk100) gonad and intestine reacted with α-DCR-1 (green) and stained with DAPI (blue). The arrowhead points to a small section of the C. elegans intestine. The arrow indicates the gonad distal tip. F. A wild type gonad with α-DCR-1 (green) and DAPI (blue). All worms were grown at 20°C. Size markers=20 µm, except 3F, which =10 µm.

Dicer and GLH-1 interact in vivo and are interdependent

Since GLH-1 and DCR-1 interact in complex and sometimes localize in close proximity at the nuclear membranes of pachytene germ cells, we investigated the fate of GLH-1 or DCR-1 when the other protein was missing or reduced. We used deletion mutants for each. The dcr-1(ok247) mutant is a protein null, whose sterile Emo phenotype was briefly described in the Introduction and by Knight and Bass (2001). There is no glh-1 null, but the most severe allele, with a somewhat weaker phenotype than glh-1(RNAi), is glh-1(gk100) (Spike et al., 2008). These worms have a 581 bp internal deletion in the glh-1 gene, removing three of four GLH-1 zinc fingers and producing a truncated GLH-1 at less than 10% of wild type levels. More than 85% of glh-1(gk100) worms are fertile at the permissive temperature of 20°C, likely due to compensation at 20°C by GLH-4 (Kuznicki et al., 2000), although these worms have reduced brood sizes. The glh-1(gk100) strain is completely sterile at 26°C (Spike et al., 2008).

To test for a possible interdependence between GLH-1 and DCR-1, western blot analyses were done for GLH-1 using wild type and dcr-1 lysates. In the dcr-1 mutant, GLH-1 was absent or dramatically reduced (Fig. 3A, lane 2; data not shown). Conversely, when DCR-1 levels were assayed in the glh-1 mutant grown at 20°C, a greater than 2.5 fold reduction of DCR-1 was seen, compared to wild type worms (Fig. 3B, lanes 1 vs. 2). Thus, GLH-1 and DCR-1 appear mutually dependent.

Assaying for GLH-1 by immunocytochemistry in dcr-1 worms confirmed the decreased levels of GLH-1 seen by western blot analysis. In the majority of homozygous dcr-1 mutants, GLH-1 was not localized to P granules or even detectable (Fig. 3C), although in about 10% of dcr-1 animals, low levels of GLH-1 staining were detected in the germline (data not shown). We next analyzed the P-granule protein PGL-1 in dcr-1 worms to determine if other constitutive P-granule components were affected in addition to GLH-1. PGL-1 localization appeared disrupted in dcr-1 mutants; in distal regions it became diffusely cytoplasmic (Fig. 3D, right inset). However, PGL-1 levels were unchanged in western blot analysis of protein lysates from dcr-1 worms (data not shown). This result is consistent with previous reports indicating PGL-1 depends upon GLH-1 to properly localize to P granules (Kawasaki et al., 1998; Spike et al., 2008). To determine if other GLH proteins were reduced in dcr-1 worms, we tested GLH-4 by western blot analysis. Unlike GLH-1, but similar to PGL-1, GLH-4 protein levels were only slightly reduced when DCR-1 was depleted when compared to wild type (Fig. S6; data not shown). These results with PGL-1 and GLH-4 reveal that loss of DCR-1 does not dramatically affect the levels of all P-granule components but does significantly alter the levels of GLH-1 and the localization of PGL-1, constitutive P-granule components, and thus likely affects the overall P-granule structure.

Confocal analysis of the glh-1 mutants after immunocytochemistry with an α-DCR-1 antibody revealed a marked reduction but not a total loss of DCR-1 (Fig. 3E), similar to results by western blot analysis (Fig. 3B). While DCR-1 was often completely missing from the glh-1 germline (Fig. 3E, arrow, germline compared to wild type in Fig. 3F), it was still present in the somatic tissue (Fig. 3E, intestine, arrowhead). That the ubiquitous DCR-1 protein is not as reduced in the glh-1 mutant as is the germline-specific GLH-1 protein in the dcr-1 strain (Fig. 3A) is likely due to DCR-1 remaining in the somatic tissue and perhaps to low germline levels of DCR-1 not associated with GLH-1. In summary, we find that in the dcr-1 null, GLH-1 levels are missing or very reduced, while levels of the P-granule proteins PGL-1 and GLH-4 are modestly affected. Similarly, the germline of the glh-1 deletion mutant shows a dramatic DCR-1 reduction.

glh-1 mRNA levels are reduced in dcr-1 mutants

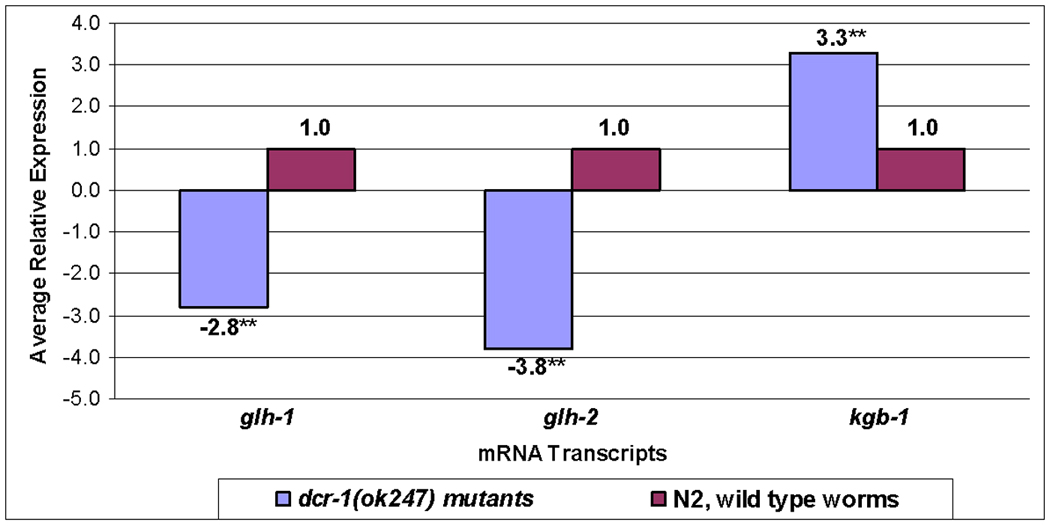

To determine whether the reduction of GLH-1 in the dcr-1 mutant reflects regulation of GLH-1 at the mRNA level, protein level, or both, we began by performing quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) on glh-1 mRNA from wild type and dcr-1 worms. glh-1 mRNA levels were reduced almost 3-fold in the dcr-1 mutant compared to wild type (Fig. 4; Table S2). In addition, mRNA levels for glh-2, glh-3, and glh-4 were tested in dcr-1 worms using primers specific for each gene (Table S1). glh-2 levels were reduced almost 4-fold while glh-3 and glh-4 levels were not significantly different than wild type (Fig. 4; Table S2).

Figure 4. glh-1 transcript levels are reduced about 3 fold in dcr-1(ok247) when compared to wild type worms.

Transcript levels of glh-1, glh-2, and kgb-1 were assayed in triplicate by qRT-PCR in dcr-1(247) as compared to wild type worms (**p value<0.001). The statistical significance of differences in relative mRNA levels was determined using the Relative Expression Software Tool (REST) 2009 (www.gene-quantification.de/rest.html). The primers used are shown in Table S1 and the numerical results are given in Table S2.

Since a reduction in DCR-1 was observed in glh-1(gk100) worms (Figs. 3B, 3E), we conducted qRT-PCR to compare dcr-1 mRNA levels in glh-1(gk100) and wild type worms and found dcr-1 mRNA was not reduced in the glh-1 mutant (Table S2). These data indicate that GLH-1 is regulated by DCR-1 at least in part at the mRNA level, and that DCR-1 protein but not its mRNA levels are affected by the reduction of GLH-1.

DCR-1 is likely targeted for degradation by KGB-1

Our previous studies reported the Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), KGB-1, targets GLH-1 for degradation via the proteasome; as wild type worms age, GLH-1 levels normally decrease, but in the null kgb-1(um3) deletion strain, GLH-1 levels increase as much as seven-fold (Orsborn et al., 2007). In light of the relationship between DCR-1 and GLH-1 reported here, we asked if DCR-1 might also be targeted for degradation by KGB-1. We first tested this possibility by growing young, wild type worms in liquid culture for a total of 6 hours and treating them with or without a JNK inhibitor for varying amounts of time. The inhibitor treatment caused DCR-1 levels to increase 3–4 fold compared to mock treated worms (0 hours with inhibitor) and to worms treated with inhibitor for only the last hour of the six hour experiment (Fig. 5A, lanes 1–2 vs. lane 3). These results suggest that DCR-1 protein levels are normally regulated by a JNK. C. elegans has only three predicted JNKs, KGB-1, KGB-2 and JNK-1, each of which is expressed both in the soma and germline. Loss of kgb-1 results in complete sterility at non-permissive temperatures while loss of kgb-2 has no detectable phenotype (Smith et al., 2002; Orsborn et al., 2007). The third family member, JNK-1, is important in the nervous system but has no observable germline effects (Villanueva et al., 2001). We then assayed for DCR-1 by western blot analysis in kgb-1 protein lysates and found DCR-1 levels were increased more than 4-fold by comparison to wild type worms grown under the same conditions (Fig. 5B, compare lanes 1 and 2).

Figure 5. DCR-1 is elevated when JNK pathways are inhibited and DCR-1 levels accumulate in kgb-1 worms.

A. Wild type worms were treated with 50 µM of the JNK inhibitor, SP600125, which was added to liquid culture media. Fifty worms treated with inhibitor for 0, 1, 2, 4 or 6 hours were collected after all had grown for 6 hrs and then analyzed by western blot for DCR-1. GLH-4 was a loading control since GLH-4 levels do not change in kgb-1(um3) worms (Orsborn et al., 2007). This image was recombined, removing the 2 and 4 hour time points, which also showed increasing DCR-1 protein levels; however, the GLH-4 control did not transfer well in that region of the membrane. B. Levels of DCR-1 were compared by western blot analysis in age-matched wild type and kgb-1(um3) adults grown at 26°C. Actin was the loading control. C. The pachytene region of a kgb-1(um3) mutant, grown at 20°C, reacted with antibodies against DCR-1 (green), and GLH-1 (red), merged. Similar strongly-reactive, large P granules were previously reported for GLH-1 in kgb-1(um3) worms (Smith et al., 2002). D. The pachytene region of a wild type gonad, with α-DCR-1 (green) and α-GLH-1 (red). E–F. DAPI-stained (blue) gonads in panels C–D, respectively. G. A section of intestine from a kgb-1(um3) worm with α-DCR-1 (green). H. A section of intestine from a wild type worm, with α-DCR-1 (green). I. Merged image of a P3-stage (8-cell) kgb-1(um3) embryo with antibodies again DCR-1 (green), GLH-1 (red), and DAPI-stained nuclei (blue). J. Merged image of a P4-stage (16-cell) wild type embryo reacted with antibodies against DCR-1 (green), GLH-1 (red), and DAPI-stained nuclei (blue). The P3 and P4 germ cell progenitors are marked (arrowheads). Each set of images comparing kgb-1(um3) and wild type worms (C/D; G/H or I/J) were taken with the same settings and exposures. Worms were grown at 20°C unless otherwise noted. Size markers=10 µm.

To determine how the loss of KGB-1 affects DCR-1, kgb-1 worms were also compared to wild type by immunocytochemistry. The kgb-1 worms were grown at the permissive temperature of 20°C to ensure the presence of normal germlines rather than the highly Emo germlines seen in kgb-1 worms at the non-permissive temperature of 26 °C (Smith et al., 2002). In Fig. 5C, the signal from DCR-1 in the kgb-1 gonads was so intense that only very low laser levels and voltages could be used for the pachytene region. Using the same settings for wild type worms, only faint signals were detected (Fig. 5D). We determined that loss of KGB-1 also affects levels of DCR-1 in the somatic tissue, as seen by comparing the kgb-1 intestine to that of wild type (Figs. 5G vs. 5H), with both images again taken using the same confocal settings. In the early embryos of wild type worms DCR-1 reactivity is weak but uniformly granular in the cytoplasm of both the somatic blastomeres and the germline progenitor cell, which is marked by GLH-1 (Figs. 5I–J; S5). In addition, DCR-1 localized to a few, but not all, of the P granules in early embryos. By comparison, in both the germline and somatic precursor cells of kgb-1 embryos, DCR-1 was at much higher levels than in wild type (Figs. 5I–J), although we cannot rule out that the increased DCR-1 and GLH-1 seen at these stages of embryogenesis might be due to the perdurance of maternal protein. Taken together, these combined data suggest that DCR-1, similar to GLH-1, is targeted for degradation by KGB-1 since in the absence of KGB-1, both GLH-1 and DCR-1 levels increase.

Since DCR-1 dramatically increases with the loss of KGB-1, both in the germline and in the soma (Figs. 5; S5), we also tested kgb-1 mRNA levels after loss of dcr-1 by qRT-PCR. Interestingly, when compared to wild type worms, kgb-1 mRNA levels were increased more than 3-fold in the dcr-1 mutants (Fig. 4), perhaps suggesting a negative feedback loop in the normal relationship of DCR-1 with KGB-1.

GLH-1 and DCR-1 regulate cytoplasmic RNP granule assembly

Large, cytoplasmic RNP granules form in the Caenorhabditis germline under a variety of conditions, including heat shock, osmotic stress, and anoxia, and in arrested oocytes occurring when C. elegans hermaphrodites become depleted of sperm (Schisa et al., 2001; Jud et al., 2007; Jud et al., 2008). These large RNP granules share characteristics with P bodies and are proposed to protect maternally-transcribed mRNAs from degradation or precocious translation until oocyte development and fertilization can continue. Components of the germline RNP granules include MEX-3, a predicted RNA binding protein, PGL-1, GLH-1 and CGH-1, another DExD/H box helicase (Jud et al., 2008; Noble et al., 2008; Table S3).

To determine if DCR-1 localizes to these large RNP granules, transgenic GFP::MEX-3 worms were heat shocked and reacted with α-DCR-1 antibody. We found DCR-1 co-localized with GFP::MEX-3 in many distinct granules in the oocytes of heat-stressed worms (Fig. S7; Table S3). DCR-1 is therefore similar to MEX-3 and CGH-1 in that it aggregates into large granules after heat shock. In contrast, PGL-1 and GLH-1 localize to RNP granules in arrested oocytes, but both these P-granule proteins remain uniformly cytoplasmic after heat shock (Jud et al., 2008; data not shown; Table S3).

The fog-2(q71) mutant worm produces oocytes but lacks sperm, such that ovulation is essentially quiescent and oocytes are in an “arrested” state even when the fog-2 animals are young adults (Schedl and Kimble, 1988). The fog-2 strain has been used extensively in studying oocyte RNP granules because of its increased numbers of arrested oocytes in young, healthy adults. The distribution of GLH-1 in fog-2 arrested oocytes differs from the small, dispersed P granules seen in actively-ovulating oocytes; instead, GLH-1 is enriched in much larger RNP granules that are cortically localized (Schisa et al., 2001; Fig. 6A). DCR-1 was also detected at high levels in the large RNP granules of arrested oocytes, and interestingly, GLH-1 granules appeared “docked” on the larger DCR-1 granules, occupying a subdomain of the RNP granules (Fig. 6A, merge). GLH-1 appeared similarly “docked” on large CGH-1 granules in fog-2 arrested oocytes (Fig. S8A). The association of DCR-1 with GLH-1 on RNP granules in arrested oocytes is not likely due to DCR-1 “tagging along” with GLH-1 during the dissociation of P granules from the nuclear membrane that occurs during oogenesis, because the majority of DCR-1 protein is not associated with P granules but is cytoplasmic or in nuclear puncta (Figs. 2D–E). In addition, the cytoplasmic levels of DCR-1 appear dramatically decreased in arrested oocytes (compare Fig. 6A to Fig. 2E); thus, we believe that most DCR-1 protein is recruited to the RNP granules from the diffuse cytoplasmic pool of DCR-1.

Figure 6. DCR-1 and GLH-1 localize to RNP granules.

A. Confocal single plane images of the five most-proximal fog-2(q71) arrested oocytes, reacted with antibodies against GLH-1 (green), DCR-1 (red), and merged. B. The gonad core of a fog-2(q71) unmated female, with antibodies against nuclear pores (left, blue), DCR-1 (middle, green), and GLH-1 (right, red). Combined localizations are seen with merged images (bottom). Size markers=5 µm.

In addition to the assembly of large RNP granules in arrested oocytes, large RNP granules also form in the syncytial gonad core of fog-2 females. Some of the components detected in oocyte RNP granules are present in these core granules including CGH-1; however, the nuclear pore proteins, and PGL-1 are excluded (Fig. S7B; Jud et al., 2008; Noble et al., 2008). We tested DCR-1 and found it was also detected at high levels in large granules in the gonad core of fog-2 worms; however, like PGL-1, GLH-1 was not detected in these large core granules (Fig. 6B). In summary, DCR-1 and GLH-1 are localized together in large RNP granules under some, but not all, conditions. DCR-1 may function with CGH-1 and other proteins in the gonad core and in oocytes after heat shock, while a DCR-1/GLH-1 complex may function with associated proteins in the RNP granules of arrested oocytes.

Since GLH-1 and DCR-1 appear to regulate the structure of P granules in the germline (Fig. 3; Kuznicki et al., 2000; Schisa et al., 2001), we next asked if either or both proteins are necessary for the assembly of the large RNP granules in oocytes. The distribution of two RNP granule components, MEX-3 and PGL-1, was first assessed in the glh-1 strain. We found that MEX-3 did not localize to RNP granules in glh-1 arrested oocytes (Fig. 7B; Table S3); however, MEX-3 granules formed in glh-1 oocytes after heat shock (Fig. 7C) that were indistinguishable from those seen in wild type after heat shock (Jud et al., 2008; data not shown). PGL-1 failed to localize to large granules in glh-1 oocytes when ovulation was arrested while after heat shock, the effect was intermediate (Figs. 7G–H). In some oocytes, abundant PGL-1 granules were detected while in adjacent oocytes, PGL-1 appeared cytoplasmic (Fig. 7H). Thus, GLH-1 appears to regulate the recruitment of MEX-3 and PGL-1 to the large RNP granules in oocytes. It was more difficult to ascertain the role of DCR-1 since the most proximal oocytes are Emo and the germline organization is generally disrupted in the dcr-1(ok247) strain (Knight and Bass, 2001; Colaiácovo et al., 2002). We first examined MEX-3 after heat shock of dcr-1 adults. In a minority of adults, in which non-Emo oocytes could be scored, a low number of small MEX-3 granules were detected; however high levels of MEX-3 remained in the cytoplasm, failing to assemble into granules (Fig. 7D). We next examined oocytes in dcr-1(RNAi); fog-2 P0 females. MEX-3 failed to localize to large granules in several individuals, remaining mostly cytoplasmic (Fig. 7E); however, this phenotype was not consistent over several trials, likely due to the inherent role of DCR-1 in the RNAi process itself (Colaiávaco et al., 2002). Overall, these data strongly suggest GLH-1, and to a lesser extent DCR-1, play upstream roles in the assembly of RNP granules in oocytes with decreased levels of either DCR-1 or GLH-1 preventing their complete assembly.

Figure 7. Reduction of GLH-1 or DCR-1 disrupts assembly of the cytoplasmic RNP granules.

MEX-3 (A–E) and PGL-1 (F–H) were visualized with their respective antibodies. Unmated fog-2(q71) females were the control for normal RNP granule assembly (A, F). MEX-3 and PGL-1 failed to localize to large granules in glh-1(gk100) worms depleted of sperm (B, G); however, GLH-1 was not essential for MEX-3 to localize to RNP granules after heat shock (C). An intermediate effect was seen for PGL-1 (H). DCR-1 appeared to regulate the localization of MEX-3 to RNP granules after heat shock and when sperm are depleted (D–E). Size markers=5 µm.

Discussion

We have uncovered a complex relationship between GLH-1, a C. elegans P-granule component, and DCR-1, the ribonuclease required for processing exogenous and endogenous siRNAs as well as miRNAs. This work has shown that loss of DCR-1 results in decreased levels of GLH-1 protein and glh-1 mRNA. Similarly, the glh-1(gk100) mutant has decreased levels of DCR-1 protein; however, levels of dcr-1 mRNA do not appear affected. Our results indicate DCR-1 and GLH-1 are targeted for degradation likely through the activity of the JNK KGB-1. Additionally, both proteins localize to large germline RNP granules in arrested oocytes where they regulate the assembly of RNP granule components. The GLH-1/DCR-1 interaction, which could occur near the nuclear pores, in cytoplasmic P granules, and possibly in the large germline RNPs, may function to transport, deposit, or regulate miRNAs and their target germline mRNAs. While many aspects of the GLH-1 and DCR-1 relationship have been explored here, many questions remain, as is the case in most early reports of relationships between two proteins critical for development.

Why are GLH-1 levels lower in dcr-1 mutants?

We currently do not know how DCR-1 affects glh-1 mRNA levels. Published microarray studies compared mRNA levels from dcr-1(ok247) mutants to those in wild type worms (Welker et al., 2007). Among the 1537 genes differentially regulated in dcr-1 mutants, 488 genes are down-regulated, 38% of which are germline-specific; this group includes glh-1. Interestingly, only 1% of the up-regulated genes are germline-specific. However, the almost three-fold decrease in glh-1 mRNA that we observed (Fig. 4) does not seem likely to completely account for the dramatic reduction of GLH-1 protein in dcr-1 mutants (Figs. 3A; 3C). GLH-1 protein could also be subject to targeted degradation by KGB-1 as a result of the loss of DCR-1; degradation of GLH-1 protein woulld likely add to or be synergistic with the loss of glh-1 mRNA. Interestingly, in the dcr-1 mutant, kgb-1 mRNA levels are elevated almost four-fold. This finding, along with other GLH-1/DCR-1/KGB-1 interactions reported here, suggests both negative and positive feedback loops operate among these three proteins.

How might KGB-1 regulate DCR-1 levels?

Our inhibitor studies indicate DCR-1 is likely targeted by a JNK for proteasomal degradation (Fig. 5A; data not shown). In addition, DCR-1 contains a consensus MAP kinase D (docking) site, RLGKKLGI (Jacobs et al., 1999; Sharrocks et al., 2000) and a putative phosphodegron motif although it is non-consensus in the second position, IDTPT (Orlicky et al., 2003; Ye et al., 2004). The finding in kgb-1(um3) worms that DCR-1 is elevated in adult somatic tissues and embryonic somatic progenitors (Fig. 5) argues that GLH-1 and DCR-1 are both KGB-1 target substrates since it seems unlikely that phosphorylation of the germline-specific GLH-1 would indirectly cause DCR-1 degradation in the soma.

What is the role of DCR-1 in C. elegans germ cell nuclei?

Our α-DCR-1 antibody allows visualization of DCR-1 in whole-mount C. elegans. Triple-labeling experiments demonstrate that GLH-1 is concentrated at the nuclear pores of germ cells where DCR-1 granules were also detected, albeit less frequently (insets, Figs. 2C–E; inserts; S4A–B). The detection of DCR-1 in both the nucleus and in the cytoplasm is similar to recent reports in the fission yeast S. pombe where the authors suggested that Dcr1 acts as a shuttling protein between the nucleus and the cytoplasm (Emmerth et al., 2010). An interesting new role for C. elegans DCR-1 was recently reported; in C. elegans embryos DCR-1 is cleaved by a caspase, generating a novel, initiator DNase from the C-terminus of DCR-1 that targets chromosomal DNA and promotes apoptosis (Nakagawa et al., 2010). This surprising new function likely occurs in the nucleus, consistent with our finding of a nuclear location for DCR-1. Unfortunately, our antibody was generated from an N-terminal DCR-1 peptide and therefore would not detect the novel C-terminal DNase.

GLH-1 is likely in the miRNA and not the RNAi pathway

Evidence points to a relationship of GLH-1 with the microRNA pathway, as is likely the case with VASA and Dicer-1 in flies (Megosh et al., 2006). We have previously reported that loss of GLH-1 does not affect the exogenous siRNA pathway; when glh-1(gk100) worms were injected with several different dsRNAs, the genes targeted for RNAi were efficiently knocked down (Spike et al., 2008). Therefore, it seems more likely this new-found relationship of GLH-1 with DCR-1 specifically relates to DCR-1 and the miRNA pathway, although we cannot discount the possibility that the DCR-1/GLH-1 complex could be involved with a rather unique mechanism, for example, with the subset of 22G small germline RNAs that are DCR-1-dependent (Claycomb, et al., 2009).

GLH-1 and DCR-1 are important components of germline RNP granules

In analyzing the RNP granules of arrested and stressed oocytes, we observed a failure of MEX-3 and PGL-1 to assemble into large RNPs in glh-1 or dcr-1 mutants (Fig. 7). Similarly, P-granule structure is disrupted when glh-1 or dcr-1 is down-regulated (Fig. 3). Therefore, GLH-1 and DCR-1 may function as critical structural components of RNP granules, in recruiting maternal mRNAs and their companion miRNAs to these storage granules. The composition and regulation of RNP components is clearly complex and variable depending on the trigger inducing their assembly (Table S3). Similarly, the components of P bodies and mammalian stress granules also differ depending on the stimulus inducing their assembly (Jud et al., 2008; Kedersha et al., 1999; Tourrière et al., 2003); however, the importance of these differences is not yet well understood.

P granules have close relationships with nuclear pore complexes

Three recent analyses in C. elegans also relate to our data revealing DCR-1 and GLH-1 in close proximity to nuclear pore complexes. The Strome laboratory focused on proteins affecting P-granule integrity and uncovered interesting links between P granules, RNAi pathway components and nuclear pores. Their RNAi screen in a PGL-1::GFP transgenic strain assayed P-granule morphology and identified 173 genes whose knock-down affected P granules (Updike and Strome, 2009). For example, knockdown of CSR-1, an Argonaute associated with endogenous, germline small RNAs, resulted in the accumulation of PGL-1, GLH-1, and RNA into additional, large perinuclear P granules (Updike and Strome, 2009). A study from the Seydoux laboratory using a similar experimental approach determined that reducing the NUP-98 nuclear pore protein with nup98(RNAi) resulted in disruption of P-granule stability and in mis-expression of the P-granule-associated mRNA nos-2 (Voronina and Seydoux, 2010), thus strengthening the hypothesis that P granules regulate the translation of maternally-transcribed mRNAs. Work from the Priess group also examined the relationship of P granules to nuclear pore complexes. In wild type worms, they found that P granules accumulate newly transcribed and exported mRNAs and that glh-1(RNAi) results in smaller P granules with reduced mRNA accumulation (Sheth et al., 2010). While PGL-1, nuclear pores, and GLH-1 were integral to these studies, our finding that DCR-1 is a binding partner of GLH-1 adds exciting new possibilities to how P granules may function.

Based on this work and the findings of others, we favor a role for the GLH-1/DCR-1 interaction such that DCR-1 may shuttle processed, germline miRNAs out of the nucleus through the nuclear pores and hand them off to GLH-1. The miRNAs might find their mRNA targets in the P granules, move to the central gonad core, and then be transported into developing oocytes (Wolke et al., 2007). Immunoprecipitations with whole worm lysates demonstrated that DCR-1 pulls-down ALG-1 and ALG-2 (Duchaine et al., 2006), as well as GLH-1 (D. Conte, U Mass, personal comm.). Perhaps a germline-specific ALG, one of the 27 C. elegans ALG/Argonautes, is integral to the GLH-1/DCR-1 complex, forming a germline RISC. The model in Figure 8 depicts aspects of the GLH-1/DCR-1 interaction uncovered with these studies. Our results indicate GLH-1 and DCR-1 physically interact, likely in or near P granules and the nuclear pores. We hypothesize that the DCR-1/GLH-1 interaction facilitates the transport of miRNAs and maternal mRNAs through nuclear pores and into P granules. When oocytes arrest, the DCR-1/GLH-1 complex may also carry out a recruiting or storage function since DCR-1 and GLH-1 are required for the complete assembly of the RNP cytoplasmic granules.

Figure 8. Model of the GLH-1/DCR-1 relationship in P granules and RNP granules.

In wild type worms, GLH-1 and DCR-1 localize to P granules to regulate the fate of maternal mRNAs and their associated miRNAs. Both proteins are subject to degradation by the proteasome, which is indicated by a PacMan© image. Under conditions of arrested ovulation, GLH-1 and DCR-1 re-localize to large RNP granules to store maternal mRNAs and recruit MEX-3, PGL-1, and perhaps CGH-1. Nuclear pores are indicated with blue ovals; miRNAs (short red lines) are located on the 3’UTRs of their target mRNAs (long black lines).

Are many aspects of the DCR-1/GLH-1 interaction conserved?

A physical interaction between Dicer and GLH-1, VASA, or MVH is now known to occur in worms, flies and mice; thus, many of the additional findings presented here including: the nuclear location of DCR-1 adjacent to nuclear pores, the roles of GLH-1 and DCR-1 in the formation of cytoplasmic RNPs, the targeting of each protein for degradation by a JNK, and the interdependence of GLH-1 and DCR-1 on each other, may be conserved “from hydra to man” (Eddy, 1975) as are the germ granules themselves.

Research Highlights

-

➢

The C. elegans P granule component GLH-1 binds to DCR-1 via pull-down analysis

-

➢

DCR-1 localizes to the cytoplasm and at the nucleus of germ cells in the gonad

-

➢

DCR-1 appears to be regulated by KGB-1, a Jun N-terminal kinase, for degradation

-

➢

GLH-1 protein and mRNA levels are much reduced in the dcr-1(ok247) mutant

-

➢

GLH-1 and DCR-1 both localize to RNP granules in stressed oocytes

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Susan Strome (UC Santa Cruz) for α-PGL-1 antibodies, Craig Mello (U. Mass.) and Thomas Duchaine (McGill, Montreal) for α-DCR-1 antibodies, Jim Priess (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center) for α-MEX-3 antibodies, and David Greenstein (U Minnesota) for α-CGH-1 antibodies. We thank Megan Wood (Central Michigan University) for performing the experiment examining the distribution of MEX-3 after RNAi of dcr-1. We thank the C. elegans Knockout Consortium for generating the glh-1(gk100) and dcr-1(ok247) strains. Several nematode strains used in this work were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the NIH National Center for Research Resources (NCRR). E.L.B. received pre-doctoral support from an MU NIH training grant 5T32GM008396. T.J.M. was supported by an MU Life Sciences pre-doctoral fellowship; J.K.M. received support from a REU supplemental award from NSF. Funding for this research was provided by National Institute of Health grant 1 R15 GM078157-01 and National Science Foundation grant MRI 0923155 to J.A.S. and by a National Science Foundation grant IOS 0819713 to K.L.B.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adler J, Parmryd I. Quantifying co-localization by correlation: the Pearson correlation coefficient is superior to the Mander's overlap coefficient. Cytometry Part A. 2010;77A:733–742. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, Kedersha N. RNA granules. J. Cell Biol. 2006;172(6):803–808. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512082. Mini-Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiri A, Keiper BD, Kawasaki I, et al. An isoform of eIF4E is a component of germ granules and is required for spermatogenesis in C. elegans. Development. 2001;128:3899–3912. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.20.3899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balagopal V, Parker R. Polysomes, P bodies and stress granules: states and fates of eukaryotic mRNAs. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009;21(3):403–408. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbee SA, Lubin AL, Evans TC. A novel function for the Sm proteins in germ granule localization during C. elegans embryogenesis. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:1502–1506. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claycomb JM, Batista PJ, Pang KM, et al. The Argonaute CSR-1 and its 22G-RNA cofactors are required for holocentric chromosome segregation. Cell. 2009;139(1):123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colaiácovo MP, Stanfield GM, Reddy KC, et al. A targeted RNAi screen for genes involved in chromosome morphogenesis and nuclear organization in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline. Genetics. 2002;162(1):113–128. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.1.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis LI, Blobel G. Identification and characterization of a nuclear pore complex protein. Cell. 1986;45(5):699–709. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90784-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, Spencer A, Morita K, et al. The developmental timing regulator AIN-1 interacts with miRISCs and may target the Argonaute protein ALG-1 to cytoplasmic P bodies in C. elegans. Mol. Cell. 2005;19:437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper BW, Mello CC, Bowerman B, et al. MEX-3 is a KH domain protein that regulates blastomere identity in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1996;87(2):205–216. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81339-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchaine TF, Wohlschlegel JA, Kennedy, et al. Functional proteomics reveals the biochemical niche of C. elegans DCR-1 in multiple small-RNA-mediated pathways. Cell. 2006;124:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy EM. Germ plasm and differentiation of the germ cell line. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1975;43:229–280. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmerth S, Schober H, Gaidatzis D, et al. Nuclear retention of fission yeast Dicer is a prerequisite for RNAi-mediated heterochromatin assembly. Dev. Cell. 2010;18:102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etemad-Moghadam B, Guo S, Kemphues KJ. Asymmetrically distributed PAR-3 protein contributes to cell polarity and spindle alignment in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1995;83(5):743–752. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findley SD, Tamanaha M, Clegg NJ, et al. Maelstrom, a Drosophila spindle-class gene, encodes a protein that co-localizes with Vasa and RDE1/AGO1 homolog, Aubergine, in nuage. Development. 2003;130(5):859–871. doi: 10.1242/dev.00310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruidl ME, Smith PA, Kuznicki KA, et al. Multiple potential germline helicases are components of the germline-specific P granules of Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:13837–13842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guedes S, Priess JR. The C. elegans MEX-1 protein is present in germline blastomeres and is a P granule component. Development. 1997;124(3):731–739. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.3.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Kemphues KJ. par-1, a gene required for establishing polarity in C. elegans embryos, encodes a putative Ser/Thr kinase that is asymmetrically distributed. Cell. 1995;81(4):611–620. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay B, Jan LY, Jan YN. A protein component of Drosophila polar granules is encoded by Vasa and has extensive sequence similarity to ATP*-dependent helicases. Cell. 1988;55(4):577–578. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs D, Glossip D, Xing H, et al. Multiple docking sites on substrate proteins form a modular system that mediates recognition by ERK MAP kinase. Genes Dev. 1999;13:163–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakymiw A, Lian S, Eystathioy T, et al. Disruption of GW bodies impairs mammalian RNA interference. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7(12):1267–1273. doi: 10.1038/ncb1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z, Xie T. Dcr-1 maintains Drosophila ovarian stem cells. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:539–544. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AR, Francis R, Schedl T. GLD-1, a cytoplasmic protein essential for oocyte differentiation, shows stage- and sex-specific expression during Caenorhabditis elegans germline development. Dev. Biol. 1996;180:165–183. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jud M, Razelun J, Bickel J, et al. Conservation of large foci formation in arrested oocytes of Caenorhabditis nematodes. Dev. Genes Evol. 2007;217(3):221–226. doi: 10.1007/s00427-006-0130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jud MC, Czerwinski MJ, Wood MP, et al. Large P body-like RNPs form in C. elegans oocytes in response to arrested ovulation, heat shock, osmotic stress, and anoxia and are regulated by the major sperm protein pathway. Dev. Biol. 2008;318:38–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath RS, Ahringer J. Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods. 2003;30(4):313–321. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki I, Shim YH, Kirchner J, et al. PGL-1, a predicted RNA-binding component of germ granules, is essential for fertility in C. elegans. Cell. 1998;94:635–645. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81605-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki I, Amiri A, Fan Y, et al. The PGL family proteins asóciate with germ granules and function redundantly in Caenorhabditis elegans germline development. Genetics. 2004;167(2):645–661. doi: 10.1534/genetics.103.023093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedersha NL, Gupta M, Li W, et al. RNA-binding proteins TIA-1 and TIAR link the phosphorylation of eIF-2alpha to the assembly of mammalian stress granules. J. Cell Biol. 1999;147:1431–1442. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.7.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight SW, Bass BL. A role for the RNase III enzyme DCR-1 in RNA interference and germ line development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;293(5538):2269–2271. doi: 10.1126/science.1062039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotaja N, Bhattacharyya SN, Jaskiewicz L, et al. The chromatoid body of male germ cells: similarity with processing bodies and presence of Dicer and mircroRNA pathway components. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:2647–2652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509333103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznicki KA, Smith PA, Leung-Chiu WM, et al. Combinatorial RNA interference indicates GLH-4 can compensate for GLH-1; these two P-granule components are critical for fertility in C. elegans. Development. 2000;13:2907–2916. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.13.2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasko PF, Ashburner M. The product of the Drosophila gene vasa is very similar to eukaryotic initiation factor-4A. Nature. 1988;335(6191):611–617. doi: 10.1038/335611a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Rivas FV, Wohlsclegel J, et al. A role for the P-body component GW182 in microRNA function. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005a;7(12):1261–1266. doi: 10.1038/ncb1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Valencia-Sanchez MA, Hannon G, et al. MicroRNA-dependent localization of targeted mRNAs to mammalian P-bodies. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005b;7(7):719–723. doi: 10.1038/ncb1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Han H, Lasko P. Vasa promotes Drosophila germline stem cell differentiation by activating Mei-P26 translation by directly interacting with a (U)-rich motif in its 3’ UTR. Genes Dev. 2009;23(23):2742–2752. doi: 10.1101/gad.1820709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megosh HB, Cox DN, Campbell C, et al. The role of PIWI and the miRNA machinery in Drosophila germline determination. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:1884–1894. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello CC, Schubert C, Draper B, et al. The PIE-1 protein and germline specification in C. elegans embryos. Nature. 1996;382(6593):710–712. doi: 10.1038/382710a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minasaki R, Puoti A, Streit A. The DEAD-box protein MEL-46 is required in the germ line of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. BMC Dev. Biol. 2009;9(35):1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-9-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murchison EP, Stein P, Xuan Z, et al. Critical roles for Dicer in the female germline. Genes Dev. 2007;21:682–683. doi: 10.1101/gad.1521307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamori I, Sassone-Corsi P. The chromatoid body of male germ cells. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(22):3503–3508. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.22.6977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa A, Shi Y, Kage-Nakadai E, Mitani S, et al. Caspase-dependent conversion of Dicer ribonuclease into a death-promoting deoxyribonuclease. Science. 2010;328:327–334. doi: 10.1126/science.1182374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro RE, Shim EY, Kohara Y, et al. cgh-1, a conserved predicted RNA helicases required for gametogenesis and protection from physiological germline apoptosis in C. elegans. Development. 2001;128:3221–3232. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.17.3221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro RE, Blackwell TK. Requirement for P Granules and meiosis for accumulation of the germline RNA helicase CGH-1. Genesis. 2005;42:172–180. doi: 10.1002/gene.20136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble SL, Allen BL, Goh LK, et al. Maternal mRNAs are regulated by diverse P body-related mRNP granules during early Caenorhabditis elegans development. J. Cell Biol. 2008;182(3):559–572. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200802128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlicky S, Tang X, Willems A, et al. Structural basis for phosphodependent substrate selection and orientation by the SCF Cdc4 ubiquitin ligase. Cell. 2003;112:243–256. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsborn AM, Li W, McEwen TJ, et al. GLH-1, the C. elegans P granule protein, is controlled by the JNK KGB-1 and by the COP9 subunit CSN-5. Development. 2007;18:3383–3392. doi: 10.1242/dev.005181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucl. Acids Res. 2001;29(9):2002–2007. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussell DL, Bennett KL. GLH-1: a germline putative RNA helicase from Caenorhabditis has four zinc fingers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:9300–9304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schisa JA, Pitt JN, Priess JR. Analysis of RNA associated with P granules in germ cells of C. elegans adults. Development. 2001;128(8):1287–1298. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.8.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schedl T, Kimble J. fog-2, a germ-line-specific sex determination gene required for hermaphrodite spermatogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1988;119(1):43–61. doi: 10.1093/genetics/119.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen GL, Blau HM. Argonaute 2/RISC resides in sites of mammalian mRNA decay known as cytoplasmic bodies. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7(6):633–636. doi: 10.1038/ncb1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrocks AD, Yang SH, Galanis A. Docking domains and substrate specificity determination for MAP kinases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:448–453. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth U, Pitt J, Dennis, et al. Perinuclear P granules are the principal sites of mRNA export in adult C. elegans germ cells. Development. 2010;137(8):1305–1314. doi: 10.1242/dev.044255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada M, Yokosawa H, Kawahara H. OMA-1 is a P granules-associated protein that is required for germline specification in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Genes Cells. 2006;11(4):383–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PA, Leung-Chiu WM, Montgomery R, et al. The GLH proteins, Caenorhabditis elegans P-granule components, associate with CSN-5 and KGB-1, proteins necessary for fertility, and with ZYX-1 a predicted cytoskeletal protein. Dev. Biol. 2002;251:333–347. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spike C, Meyer N, Racen E, et al. Genetic analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans GLH family of P-granule proteins. Genetics. 2008;178(4):1973–1987. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.083469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strome S, Lehmann R. Germ versus soma decisions: lessons from flies and worms. Science. 2007;316(5823):392–393. doi: 10.1126/science.1140846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strome S, Wood WB. Immunofluorescence visualization of germline-specific cytoplasmic granules in embryos, larvae, and adults of Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1982;79:1558–1562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.5.1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strome S, Wood WB. Generation of asymmetry and segregation of germline granules in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1983;35:15–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styhler S, Nakamura A, Swan A, et al. Vasa is required for GURKEN accumulation in the oocyte, and is involved in oocyte differentiation and germline cyst development. Development. 1998;125(9):1569–1578. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.9.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam K, Seydoux G. nos-1 and nos-2, two genes related to Drosophila nanos, regulate primordial germ cell development and survival in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1999;126(21):4861–4871. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.21.4861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabara H, Hill RJ, Mello CC, et al. pos-1 encodes a cytoplasmic zinc-finger proteín essential for germline specification in C. elegans. Development. 1999;126(1):1–11. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomancak P, Guichet A, Zavorszky P, et al. Oocyte polarity depends on regulation of gurken by Vasa. Development. 1998;125(9):1723–1732. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.9.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourrière H, Chebli K, Zekri L, et al. The RasGAP-associated endoribonuclease G3BP assembles stress granules. J. Cell Biol. 2003;160:823–831. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Updike DL, Strome S. A genomewide RNAi screen for genes that affect the stability, distribution and function of P granules in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2009;183:1397–1419. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.110171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva A, Lozano J, Morales A, et al. jkk-1 and mek-1 regulate body movement coordination and response to heavy metals through jnk-1 in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J. 2001;20(18):5114–5128. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.18.5114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voronina E, Seydoux G. The nucleoporin Nup98 is required for the integrity and function of germline P granules in C. elegans. Development. 2010;137(9):1441–1450. doi: 10.1242/dev.047654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welker NC, Habig JW, Bass BL. Genes mis-regulated in C. elegans deficient in Dicer, RDE-4, or RDE-1 are enriched for innate immunity genes. RNA. 2007;13(7):1090–1102. doi: 10.1261/rna.542107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickens M, Goldstrohm A. A place to die, a place to sleep. Science. 2003;300:753–755. doi: 10.1126/science.1084512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolke U, Jezuit EA, Priess JR. Actin-dependent cytoplasmic streaming in C. elegans oogenesis. Development. 2007;134(12):2227–2236. doi: 10.1242/dev.004952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X, Nalepa G, Welcker M, et al. Recognition of phosphodegron motifs in human cyclin E by the SCF Fbw7 ubiquitin ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:50110–50119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.