Abstract

Background & Aims

Prograstrin induces proliferation in colon crypts by activating p65NF-κ B and β-catenin. We investigated whether Annexin A2 (AnxA2), a progastrin receptor, activates NF-κB and β-catenin in vivo.

Method

ANXA2-null (ANXA2− /−) and wild-type (ANXA2+/+) mice were studied, along with clones of progastrin-responsive HEK-293 cells that stably expressed full-length progastrin (HEK-mGAS) or an empty-vector (HEK-C). Small interfering RNA was used to downregulate AnxA2, p65NF-κB, and β-catenin in cells.

Results

Proliferation and activation of p65 and β-catenin increased significantly in HEK-mGAS, compared with HEK-C clones. HEK-mGAS cells had a 2–4-fold increase in relative levels of c-Myc, COX-2, CyclinD1, DCAMKL+1, and CD44, compared with HEK-C clones. Down-regulation of AnxA2 in HEK-mGAS clones reduced activation of NF-κB and β-catenin, as well as levels of DCAMKL+1. Surprisingly, downregulation of β-catenin had no effect on activation of p65NF-κB, whereas down-regulation of p65 significantly reduced activation of β-catenin in HEK-mGAS clones. Loss of either p65 or β-catenin significantly reduced proliferation of HEK-mGAS clones, indicating that both factors are required for the proliferative effects of progastrin. Lengths of colon crypts and levels of p65, β-catenin, DCAMKL+1, and CD44 were significantly higher in ANXA2+/+ mice compared to corresponding values measured in either ANXA2− /− mice injected with progastrin or ANXA2+/+ and ANXA2− /− mice injected with saline.

Conclusions

AnxA2 expression is required for the biological effects of progastrin in vivo and in vitro, and mediates the stimulatory effect of progastrin on p65NF-κ, β-catenin, and the putative stem-cell markers DCAMKL+1 and CD44. AnxA2 might therefore mediate the hyperproliferative and co-carcinogenic effects of progastrin.

Keywords: Stem and progenitor cells, colorectal cancer, signaling, AnnexinA2−/− mice

INTRODUCTION

Accumulating evidence suggests that exogenous/autocrine gastrins up-regulate proliferation/co-carcinogenesis of gastrointestinal and pancreatic cancers (1,2). Progastrin (PG) and glycine-extended gastrins (G-Gly) are predominant forms found in colonic/ovarian/pancreatic/lung cancers (1). Progastrin exerts potent proliferative/anti-apoptotic effects on target cells in vitro and in vivo (3–7). Transgenic mice over-expressing progastrin are at a high risk for developing pre-neoplastic/neoplastic colonic lesions in response to azoxymethane (8–11).

Under physiological conditions, only processed forms of gastrins (G17/G34) are present in the circulation (1). In certain disease states, however, elevated levels of circulating progastrin are detected (1). Since co-carcinogenic effects of progastrin are measured in Fabp-PG mice, expressing ‘pathophysiologic’ concentrations of hPG (8), elevated levels of circulating progastrin may increase the risk of tumor development, in response to DNA damage. We reported a critical role of NF-κB activation in mediating progastrin-induced proliferation/anti-apoptosis in vitro and in vivo (7,12). Additionally we reported the novel possibility that β-catenin activation in response to progastrin is downstream of p65NF-κB activation in vivo (13). It is, however, not known whether β-catenin also signals to p65NF-κB, and whether activation of both p65 and β-catenin are required for mediating growth effects of progastrin. We addressed these questions using a gastrin/progastrin responsive cell line (HEK-293) (14), since HEK-293 cells are amiable to multiple-transfections.

Annexin A2 (AnxA2) represents a non-conventional ‘receptor’ for progastrin/gastrin peptides (15) Down-regulation of AnxA2 reduced growth-stimulatory effects of progastrin on various target cells by ~50-80% (15). It is, however, not known whether progastrin binding to AnxA2 is required for activating NF-κB and/or β-catenin, in vitro and in vivo. We employed ANXA2− /− mice and progastrin-expressing clones of HEK-293 cells to address this question.

Recent reports suggest that progastrin up-regulates the census of cells expressing the putative stem cell marker, DCAMKL+1 in colonic crypts (11). Stem/progenitor cell marker, CD44, is up-regulated in cancer cells that over-express autocrine progastrin (16). In the current studies we examined whether autocrine progastrin directly up-regulates DCAMKL+1 expression and whether AnxA2 expression is required for measuring stimulatory effects of progastrin on DCAMKL+1/CD44 levels.

Results of the current study strongly suggest that AnxA2 expression is required for up-regulation of NF-κB, β-catenin, CD44 and DCAMKL+1, in response to progastrin, both in vitro and in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Antibodies used included anti-total-p65, anti-phospho-p65NF-κB(Ser276), anti-phospho-p44/42-ERKs, anti-phospho-p38MAPkinase, anti-PCNA, anti-CyclinD1 (Cell Signaling Technology, MA), anti-COX-2 (Chemicon International, MA), anti-c-Myc (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA), anti-β-actin (total) (Sigma), anti-AnxA2, anti-CD44 and anti-DCAMKL+1 (BD Biosciences). Recombinant-human-progastrin (rhPG) and anti-progastrin-antibodies were generated in our laboratory (4,8). NF-κB DNAbinding-kit was from Active Motif (Carlsbad, CA). Anti-IgG, coupled to horseradish-peroxidase, were from Amersham. Alexa-Flour-594 and Alexa-Flour-488 coupled secondary-IgG were from Invitrogen. Luciferase reporter plasmids, for measuring activation of β-catenin (TOPFlash-wild type and FOPFlash-mutant) were obtained from Dr. Bert Vogelstein (John Hopkins).

Cell Culture

HEK-293 cells (obtained from ATCC) were cultured in DMEMF12 medium supplemented with 10% FCS containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin in a humid atmosphere at 37°C with 5% CO2. The cell line was regularly monitored for absence of mycoplasma.

Generation of HEK-293 clones, stably over-expressing full-length progastrin (hPG)

An eukaryotic expression plasmid was created for expressing full-length coding sequence of hGAS gene, mutated at three di-basic sites (R57A-R58A/K74A-K75A/R94A-R95A), as previously described (8). HEK-293 clones, stably expressing full-length hPG (HEK-mGAS), were generated as described (17). Vector transfected clones (HEK-C) served as controls.

Transient transfection

Cells were transiently transfected with indicated plasmids, including promoter-reporter-plasmids (TOPFlash/FOPFlash) for measuring activation of β-catenin, as described (7).

Transfection with double-stranded siRNA oliglionucleotides

Smart Pool of target-specific-siRNA and Non-Targeting (control) siRNA Pool, were obtained from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). Cells, seeded in six well dishes, were transfected with 1-1.5μg of specific/control-siRNA using Fugene (Roche, IN). Transfected cells were propagated in normal medium containing 10% FCS for 48–72h, and processed for immunoblot-analysis.

In vitro growth assays

Cell growth was quantified in either an MTT assay or cell-count assay as described (4,18).

Immunoblot analysis

Cell/nuclear extracts were prepared from isolated colonic-crypts and from control/treated cells in culture. Samples were processed for electrophoresis and transferred to PVDF-membranes, as described (7). Blots were cut into horizontal strips containing target or loading-control proteins, and processed for immunoblot-analysis. Antigen-antibody complexes were detected with chemiluminescence-reagentkit (GE Health Care). Membrane strips containing either target or loading control proteins were simultaneously exposed to autoradiographic-film(s). Relative band-density on scanned autoradiograms was analyzed densitometrically, using Image J Program (rsb.info.nih.gove/ij/download), and expressed as a ratio of β-actin or total kinase levels in the corresponding samples.

DNA binding assay

Activation NF-κB was determined using TransAM p65NF-κB transcription factor assay, as described (7,12).

Promoter-reporter Assays

Cells transfected for 24h with either TOPFlash or FOPFlash plasmids, were either treated (wtHEK-293 cells) or untreated (HEK-C/HEK-mGAS cells) with rhPG for 24–48h, followed by lysis. Luciferase Assay Reagent (Promega) was added to aliquots of samples and luciferase units measured with a luminometer (Dynex Technologies). Cells transfected with FOPFlash plasmid served as negative controls. In some experiments, cells were pre-transfected with the indicated siRNA-oligonucleotides.

Membrane binding and internalization of progastrin/AnxA2

Cells were seeded on glass cover slips, cultured overnight in complete growth medium, washed with PBS and incubated for 0–15min with 10nM rhPG in DMEM containing 0.1% serum at 37°C. Binding was terminated with ice-cold PBS, followed by fixation in Acetone:Methanol (1:1) for 20min at −20°C. Fixed cells were washed with PBS, blocked with 5% BSA, and incubated at 4°C with rabbit anti-rhPG-antibody (1:200) and mouse anti-AnxA2-antibody (1:500). Excess antibody was removed, and samples incubated with Goat-anti-rabbit-IgG coupled to Alexa-Flour-594 (for detecting progastrin) and rabbit-anti-mouse-IgG coupled to Alexa-Flour-488 (for detecting AnxA2). Excess antibody was removed, and cells incubated with DAPI for 5min. Cover slips were mounted on glass slides with anti-fade-fixative (DAKO), and images acquired with Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (META, NY). Images were analyzed using METAMORPH, v6.0 software.

Treatment of ANXA2−/− /ANXA2+/+ mice with progastrin, and analysis of colons/colonic crypts

ANXA2− /− mice, on the C57Bl/6 background were generated as described (19), and shipped to animal facilities at UTMB. C57Bl/J6-WT (ANXA2+/+) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Mice (~14wk old) were injected in groups of 5–10 with rhPG (1–10nM), i.p., 2X/day for 10 days as described (13), and then euthanized. Colons were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and processed for immunohistochemical/immunofluorescence staining, as described (12,13). Colonic crypts were also isolated and processed for Immunoblots as described (12,13).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean±SEM of values obtained from 4–8 samples from 2–3 experiments. To test significant differences between means, nonparametric Mann-Whitney test was employed using Statview 4.1 (Abacus Concepts, Inc.); P values<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

HEK-293 cells respond to growth effects of gastrins (14). In the current study we demonstrate for the first time, that full-length-progastrin (rhPG) also stimulates growth of HEK-293 cells (Supplementary Fig1A), and activates both p65 and β-catenin in HEK-293 cells, in vitro (Supplementary Figs1B–D).

Generation of HEK-293 clones, overexpressing progastrin

HEK-293 clones were generated for stably expressing either the empty vector (HEK-C) or triple mutant-hGastrin gene (HEK-mGAS) as previously described (8,17). As a result, HEK-mGAS cells expressed full-length progastrin, which was resistant to processing into smaller fragments (Fig1A). Basal growth of HEK-mGAS clones was ~2-fold higher than that of HEK-C clones, irrespective of serum concentration, confirming mitogenic effects of autocrine progastrin (Fig1B). PCNA levels were increased ~2-fold in HEK-mGAS versus HEK-C clones (Fig1C).

Fig1.

A–C – Proliferative potential of HEK-mGAS and HEK-C cells. (A) Expression of full length 9-kDa progastrin peptide by HEK-mGAS clones. (B) Growth response of an equal number of HEK-C and HEK-mGAS cells to increasing concentrations of FCS, measured in an MTT assay. Absorbance values are plotted against FCS concentrations. Each value represents data from 6 separate wells/experiment, from a representative of 2 similar experiments. (C) Relative levels of PCNA in the cellular lysates of sub-confluent clones, growing in 5% FCS, measured by immunoblot analysis. A representative blot from a total of 6 blots from 3 experiments is presented. Basal intensity of bands, determined densitometrically, is plotted as percent change in the ratio of PCNA: β-actin (ratio for HEK-C cells was arbitrarily designated 100%); data from 6 blots are presented as mean±SEM, in bar graphs. *=p<0.05 versus HEK-C values. Fig1D. Co-localization and internalization of progastrin/AnxA2 complexes, in response to exogenous progastrin (PG). wtHEK-293 cells on glass cover slips were incubated with progastrin for indicated time periods and processed for detection of progastrin/AnxA2 by confocal microscopy. Red-fluorescence=progastrin-staining, green fluorescence=AnxA2-staining. Co-localization of progastrin/AnxA2 appears bright yellow in merged images at 60x magnification. Insets presented for merged images are computer enhanced. Co-localized progastrin/AnxA2 on membranes (short arrows) and intracellularly (long arrows) are shown.

AnxA2 is expressed on membranes of HEK-293 cells

HEK-293 cells, on glass cover slips, were stimulated with 10nM progastrin. Strong co-localization of progastrin with membrane-associated AnxA2 was observed at 0–2min (Fig1D). Within 5–15 min, majority of progastrin/AnxA2 complexes were observed as punctate bodies in the perinuclear region (Fig1D), suggesting intra-cellular translocation of AnxA2/PG complexes.

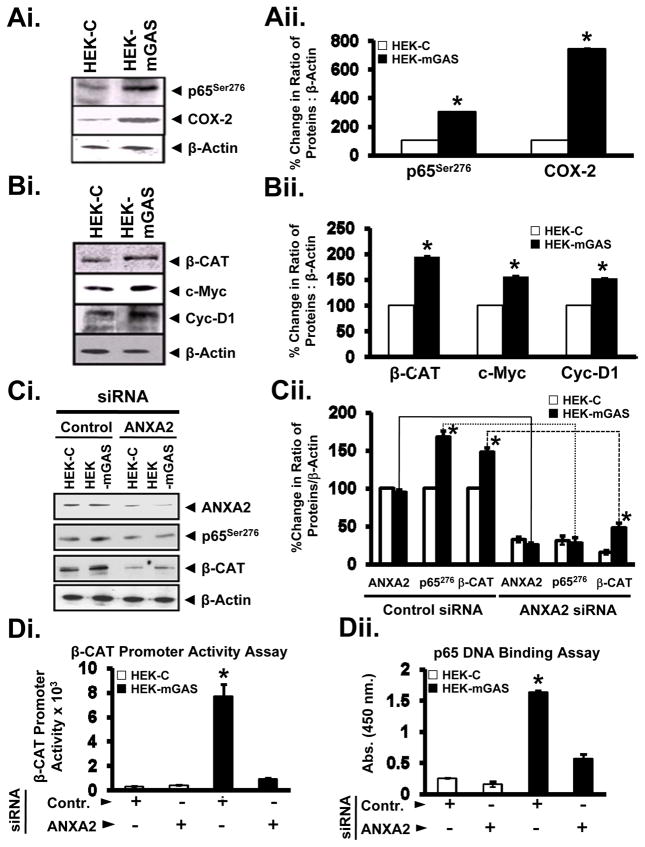

AnxA2 expression is required for measuring activation of NF-κB/β-catenin in response to progastrin in vitro

Initially, we confirmed a significant increase in relative levels of p65276/COX2 (Fig2A), β-catenin/c-Myc/cyclinD1 (Fig2B), as a readout of activated p65/β-catenin, in (non-transfected) HEK-mGAS versus HEK-C clones. HEK-mGAS/HEK-C cells were transfected with either control or AnxA2-specific-siRNA. Transfection with control-siRNA had no effect on p65276/total-β-catenin levels in HEK-mGAS and HEK-C cells (Fig2C). However, transfection with AnxA2-siRNA resulted in attenuation of activated p65 and significant loss of total β-catenin in HEK-mGAS clones (Fig2C). HEK-C cells demonstrated negligible activation of β-catenin/NF-κB in both control-siRNA and AnxA2-siRNA transfected cells (Figs2D, E). HEK-mGAS cells transfected with control-siRNA demonstrated significant activation of β-catenin and NF-κB (Figs2D, E), similar to that measured in progastrin simulated wtHEK-293 cells (Supplementary Fig1). HEK-mGAS cells transfected with AnxA2-siRNA, on the other hand, demonstrated significant attenuation in activated β-catenin (Fig2D) and NF-κB (Fig2E), compared to that observed in HEK-mGAS cells transfected with control-siRNA. Thus, even though increased stabilization of total β-catenin was measured in AnxA2-siRNA transfected HEK-mGAS cells (Fig2C), levels of activated β-catenin remained negligible in these cells (Fig2D). The data suggest that AnxA2 expression is required for measuring activation of both NF-κB/β-catenin at the nuclear level, in response to autocrine progastrin.

Fig2.

A, B. Activation of p65NF-κB/β-catenin in response to autocrine-progastrin in HEK-mGAS clones. Relative levels of pp65Ser276/COX-2 (A), and β-catenin/c-Myc/CyclinD1/β-actin (B) in cellular lysates of HEK-mGAS versus HEK-C cells, measured by immunoblot analysis, are presented. In A, B, data from a representative blot of 4 blots/2 experiments are presented. In A, B, percent change in ratio of the indicated proteins to β-actin, are presented as mean±SEM of data from 4 blots, as described in Fig1 legend. In each case *=p<0.05 versus HEK-C values. Fig2C. Down-regulation of AnxA2 in HEK-mGAS cells results in loss of relative-levels of pp65NF-κB and β-catenin. HEK-C/HEK-mGAS clones were treated with either control-siRNA or AnxA2-siRNA, and cellular-lysates processed for immunoblot analysis. β-actin was analyzed as an internal control. Representative blots from a total of 4 blots/2 experiments are presented in the left panel. In the right panel, data from 4 blots are presented as percent change in the ratio of indicated proteins: β-actin as mean±SEM. *=p<0.05 versus HEK-C values. Figs2D–E. Down-regulation of AnxA2 in HEK-mGAS cells results in loss of activation of NF-κB and β-catenin. D. HEK-C/HEK-mGAS cells, were transfected with either control- or AnxA2-specific-siRNA for 48h, followed by transfection with either FOPFlash or TOPFlash plasmids. 24h after transfection, promoter-activity was measured in terms of luciferase-units, and data from 6 separate samples/2 experiments are presented. E. Cells were transfected with either control- or AnxA2-specific-siRNA for 48h, followed by preparation of nuclear-extracts, and processed for measuring binding of activated-NF-κB in a DNA-binding-assay; data from 6 separate samples/2 experiments are presented as mean±SEM.

Progastrin up-regulates stem cell markers, DCAMKL/CD44 in vitro in an AnxA2-dependent manner

In cells stained with antibodies against DCAMKL+1/CD44, intensity of immunohistochemical staining/cell, and proportion of labeled cells were higher in HEK-mGAS versus HEK-C cells (Fig3A, Supplementary Fig2). Up-regulation of DCAMKL+1/CD44 expression in HEK-mGAS cells was further confirmed by Immunoblot analysis (Figs3B, C). To examine the role of AnxA2, cells were transfected with either control or AnxA2-siRNA (Figs3B, C). Control-siRNA had no effect on the increase in DCAMKL+1/CD44 seen in HEK-mGAS versus HEK-C cells. Treatment with AnxA2-siRNA, however, almost completely reversed stimulatory effect of autocrine progastrin on DCAMKL+1 levels. Surprisingly, CD44 levels remained elevated in AnxA2-siRNA treated HEK-mGAS cells (Figs3B, C), suggesting that up-regulation of CD44 may be more distal than stimulatory effect on DCAMKL+1.

Fig3.

A–C. Autocrine progastrin up-regulates DCAMKL+1/CD44 in HEK-mGAS versus HEK-C cells in an AnxA2-dependent manner. A. HEK-C/HEK-mGAS cells growing on cover-slips were stained for the indicated stem cell marker, as described in legend of Fig1D. 3B–C. HEK-C/HEK-mGAS cells were transfected with either control or specific AnxA2-siRNA, followed by preparation of cellular-extracts after 48h. Lysates were processed for immunoblot analysis, and data from a representative blot from a total of 4 blots/2 experiments are shown in B. Data from 4 blots are presented as percent change in the ratio of indicated proteins: β-actin as mean±SEM in C. *=p<0.05 versus HEK-C values. Figs3D, E. Effect of down-regulating β-catenin/p65NF-κB on growth of HEK-C/HEK-mGAS cells. HEK-C/HEK-mGAS cells in culture were transfected with either control or β-catenin/p65 specific-siRNA. After 72h, cells were either processed for immunoblot analysis (FigD) or counted (E). Cell-numbers in 6 separate dishes/experiment were measured and presented as mean±SEM in Cii. Data presented are representative of 3 similar experiments. *=p<0.05 versus corresponding HEK-C values; †=p<0.05 versus corresponding control-siRNA values.

Activation of both β-catenin and p65NF-κB are required for measuring proliferative response of HEK-mGAS cells to autocrine progastrin

Cells growing in the presence of 1% FCS were treated with siRNA directed against either β-catenin or p65NF-κB. siGenome non-targeting pool of siRNAs served as controls. β-catenin/p65 expression was reduced by >80% in samples treated with target-specific-siRNA (Fig3D). The growth response was examined 48–72h after siRNA treatment in a cell-count assay. The number of control-siRNA transfected HEK-mGAS cells was ~2-3-fold higher than that of control-siRNA transfected HEK-C cells (Fig3E). Total number of HEK-C cells, transfected with either β-catenin-siRNA or p65-siRNA, was only slightly lower compared to that of control-siRNA transfected HEK-C cells (Fig3E). Growth of HEK-mGAS clones was significantly reduced to control levels upon transfection with p65-siRNA, and significantly reduced upon transfection with β-catenin-siRNA (Fig3E). However, growth of HEK-mGAS cells transfected with β-catenin-siRNA remained elevated compared to HEK-C cells (Fig3E), suggesting a critical role of p65NF-κB for mediating growth effects of progastrin.

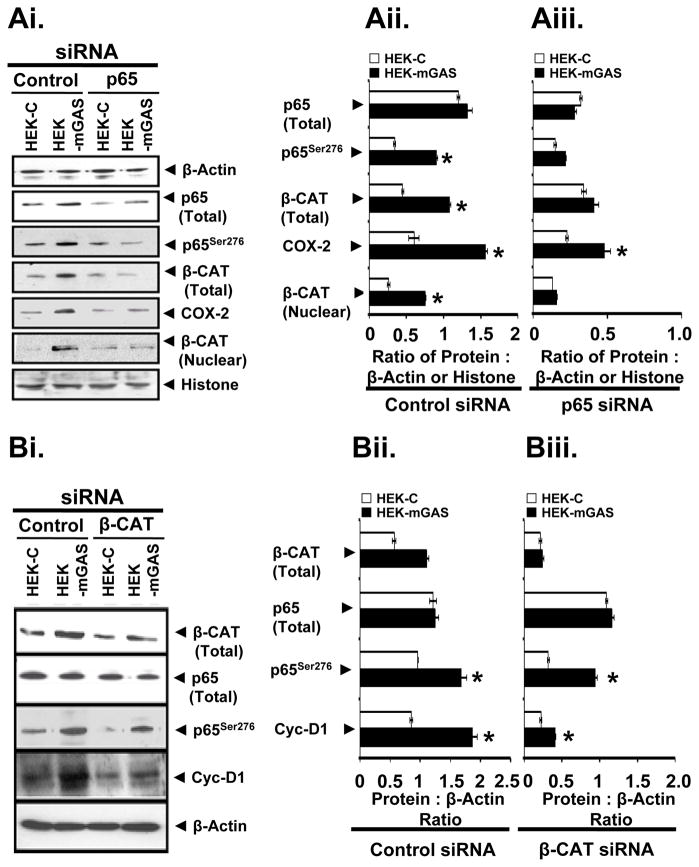

Down-regulation of p65NF-κB attenuates β-catenin activation in HEK-mGAS clones

HEK-mGAS cells transfected with control-siRNA demonstrated significant elevation in p65276, total-β-catenin, COX-2 and nuclear-β-catenin, compared to that in control-siRNA transfected HEK-C cells (Figs4A, B). HEK-mGAS and HEK-C cells, transfected with p65-siRNA were down-regulated for p65 expression by ~80% (Figs4A, B). Down-regulation of p65NF-κB expression, attenuated the increase in p65276, total β-catenin and nuclear-β-catenin in HEK-mGAS cells (Figs4A, B). Relative levels of COX-2, while significantly reduced in p65-siRNA transfected cells, remained elevated in HEK-mGAS versus HEK-C clones (Figs4A, B), suggesting that factors in addition to p65/β-catenin may maintain basal levels of COX-2 in HEK-mGAS cells.

Fig4.

A, B. Down-regulation of p65NF-κB attenuates β-catenin activation in HEK-mGAS cells. Cells were transfected with either control-siRNA or p65NF-κB-specific-siRNA, and processed for immunoblot analysis. Representative blots from a total of 4 blots/2 experiments, are presented in A. β-actin and histone levels were used as internal-controls for cellular/nuclear lysates, respectively. Ratio of indicated proteins to either β-actin (total-p65/p65276/total-β-catenin/COX-2) or histone (nuclear-β-catenin) are presented as mean±SEM from all 4 blots in B, left panel: control-siRNA and Right panel: p65-specific-siRNA. *=p<0.05 versus corresponding HEK-C values. Fig4B. Activation of p65NF-κB is independent of β-catenin activation in HEK-mGAS cells. Cells were transfected with either control-siRNA or β-catenin-specific-siRNA and processed for immunoblot analysis of cellular-lysates. β-actin levels were measured as an internal-control. Representative blots of a total of 4 blots/2 experiments are presented in C. Ratio of indicated proteins: β-actin, determined from densitometric-analysis of immunoblot bands, is presented as mean±SEM of data from all 4 blots in D (as described above for B). *=p<0.05 versus HEK-C values. β-cat = β-catenin; CycDi = Cyclin D1.

Activation of p65NF-κB is independent of β-catenin activation in HEK-mGAS cells

Relative levels of total β-catenin, p65276 and cyclin-D1 were significantly elevated in control-siRNA transfected HEK-mGAS versus HEK-C cells (Figs4C, D). Transfection of β-catenin-siRNA reduced β-catenin expression by >60–80% in HEK-C/HEK-mGAS cells (Figs4C, D). However, loss of β-catenin expression had no effect on expression of p65NF-κB in either HEK-C or HEK-mGAS cells (Figs4C, D). Relative levels of pp65 remained significantly elevated in β-catenin-siRNA-transfected HEK-mGAS versus HEK-C cells (Figs4C, D), strongly suggesting that phosphorylation-related activation of p65NF-κB is independent of β-catenin, in response to progastrin. Relative levels of cyclin-D1 in HEK-mGAS cells, transfected with β-catenin versus control-siRNA, were significantly reduced. However, levels of cyclin-D1 remained slightly elevated in HEK-mGAS versus HEK-C cells (Figs4C, D). Thus, data in Fig4, demonstrate for the first time, that while β-catenin activation is downstream of NF-κB, activation of NF-κB, in response to autocrine-progastrin, it is independent of β-catenin, as diagrammatically presented in Supplementary Fig3, in relation to what is known in this field.

AnxA2 expression is required for signaling growth effects of progastrin to colonic crypt cells, in vivo

ANXA2− /− ANXA2+/+ mice following genotyping were confirmed (Fig5A). Mice were treated with either rhPG or saline as described in Methods. In response to 1-10nM rhPG, significant increase in the length of colonic crypts was observed in ANXA2+/+, but not ANXA2− /− mice. Data obtained with 10nM PG are shown in Figs5B, C&Supplementary Fig4. Representative immunohistochemical data obtained with 10nM PG are shown in Fig5B, and representative colonic crypts isolated from the different groups of mice are presented in Supplementary Fig4. Relative levels of pp65Ser276/cellular β-catenin were significantly increased in rhPG versus saline-treated ANXA2+/+ mice (Fig5D). Relative levels of p65/β-catenin from progastrin versus saline-treated ANXA2− /− mice, on the other hand, were similar (Fig5D), strongly implying that AnxA2 expression is required for activating NF-κB/β-catenin in colonic crypts of mice, in response to progastrin.

Fig5. ANXA2 expression is required for the growth/signaling effects of progastrin in vivo.

A. Representative immunoblot data demonstrating absence of AnxA2 expression in colonic crypts of ANXA2− /− mice. B. Representative tissue sections from mid-colons of ANXA2+/+/ ANXA2− /− mice, treated with either saline (onM) or 10nM-rhPG. Dashed lines represent average length of colonic crypts in the indicated mice. C. To obtain accurate measurements of colonic-crypt lengths, colons were processed for preparation of isolated colonic-crypts (Supplementary Fig4), and lengths measured as previously described (12,13). Each bargraph=mean±SEM of 30-50 isolated-crypt lengths from 3–5 mice. *=p<0.05 versus control (saline-treated) mice:†=p<0.05 versus respective ANXA2+/+ levels. D. Isolated colonic crypts from mid-colons of the indicated genotypes were processed for immunoblot analysis. Representative blots of 6–8 blots from 3–4 mice are shown in left panel. Percent change in the ratio of p65Ser276:total p65 and β-catenin: β-actin, is shown in right panel; each group represents mean±SEM of data from 3–5 separate mice. *=p<0.05 versus corresponding-control (0nM PG) group.

Relative levels of CD44/DCAMKL+1 were also increased by ~1.5-2-fold in colonic crypt cells of progastrin-treated ANXA2+/+ mice (Figs6A, B), and reflected the increase in percent cells positive for DCAMKL+1/CD44 in colonic crypts of rhPG versus saline-treated ANXA2− /− mice (Figs6C, D, Supplementary Fig5). In ANXA2− /− mice, on the other hand, significant differences were not measured in either DCAMKL+1 or CD44 expression, in response to PG stimulation (Figs6A, B). Percentage of cells positive for CD44 in rhPG versus saline-treated ANXA2− /− mice were also not different (Figs6C, D, Supplementary Fig5). However, proportion of DCAMKL+1 positive cells, remained slightly elevated in rhPG versus saline-treated ANXA2− /− mice (Figs6c, D, Supplementary Fig5). An important finding was that cells staining for CD44/DCAMKL+1 were distinctly different, and did not co-stain with each other.

Fig6. AnxA2 expression is required for stimulatory effect of progastrin on CD44/DCAMKL+1 expression in colonic crypts.

Colonic crypts were isolated from the mice and processed for immunoblot analysis as described in Fig5. Immunoblots from a representative mouse, of a total of 3-5 mouse blots, are shown in A. Immunoblot data from all the mice are presented in B, as percent change in the ratio of indicated proteins: β-actin. *=p<0.05 versus corresponding control (0nM PG) values. C. Mouse colon sections from the indicated 4 groups of mice were processed for immunofluorescence staining with either anti-DCAMKL+1-IgG (green) or anti-CD44-IgG (red) (Supplementary Fig5). Representative enlarged images from stained colonic crypts of indicated mice are presented in C. Relative staining/cell for both DCAMKL+1/CD44 appears to be increased in PG-treated ANXA2+/+ colonic crypts, but no significant differences were observed in PG-treated ANXA2− /− mice compared to corresponding controls (Figs6C, D, Supplementary Fig5). The percent cells (within a viewing field at 20X magnification) positive for either DCAMKL+1 or CD44 were counted in ten sections from 3-5 mice. Data are presented as mean±SEM in D. *=p<0.05 versus corresponding control mouse sections; †=p<0.05 versus corresponding ANXA2+/+ levels.

DISCUSSION

Proliferative effects of precursor gastrins (progastrin/G-Gly) are reportedly mediated by novel receptor mechanisms, distinct from CCK1R/CCK2R, in vitro (1,4,18,20) and in vivo (21,22). Several years ago we had identified a 33–36 kDa protein with high-affinity for progastrin/gastrin peptides (23). Recently, we discovered that AnxA2 represents the novel p36 ‘receptor’ protein (15). Unlike CCK2R-antibodies, AnxA2-antibodies blocked growth effects of progastrin on target cells in vitro (7,15). In addition, AnxA2 expression was required for the growth effects of progastrin on colon cancer cells (15). Only proliferative/anti-apoptotic effects of progastrin have been reported (1). Amidated-gastrins, however, either stimulate (24) or inhibit (25) growth of target cells in vitro via CCK2R. Pro-apoptotic effects of amidated-gastrins, via CCK2R have also been reported in vivo (24,26); a recent study, however, reported that CCK2R expression may be required for measuring co-carcinogenic effects of pharmacological levels of progastrin on colons of transgenic hGAS mice (11). In the current studies, we demonstrate for the first time that AnxA2 expression is required for activating both NF-κB and β-catenin signaling pathways, and for the hyperproliferative effect of progastrin on colonic crypts in vivo.

Because anti-AnxA2-antibodies block binding of AnxA2 to progastrin, and significantly attenuate growth effect of exogenous progastrin on AR42J/IEC-18 cells in vitro (7,15), we hypothesized that membrane-associated-extracellular AnxA2 is required for growth effects of progastrin. Presence of extracellular, membrane-associated AnxA2 has been reported on several cancer cells (27–31). Results of the current study provide further evidence for the presence of membrane-associated AnxA2 on HEK-293 cells and suggest that progastrin-AnxA2 complexes are rapidly internalized after binding (Fig1C). Interestingly, in prostate cancers, cytoplasmic staining of AnxA2 was detected, while in benign prostatic glands, AnxA2 was localized to plasma membranes (32). TM601, a 36amino-acid synthetic-peptide, specifically binds extracellular-AnxA2 on endothelial and tumor cells and was reported to be internalized by proliferating endothelial cells, resulting in neo-angiogenesis (30). Paracrine/endocrine progastrin induces hyperproliferation of proximal-colonic-crypts associated with internalization of AnxA2, while in the non-responsive distal-crypts, AnxA2 remains localized to plasma membranes (12). Thus, internalization of AnxA2/ligand-complexes, may represent a hallmark of cells, responsive to proliferative agents, such as progastrin and TM601.

Because AnxA2 lacks transmembrane domain(s), mechanisms mediating internalization of AnxA2/progastrin remain speculative. AnxA2 may be anchored to the cell surface by AnxA2-receptor (33, Supplementary Fig3). Binding of AnxA2 to AnxA2-receptor is reportedly essential for metastasis of prostate cancer cells (34). knock-down of AnxA2 inhibits metastatic invasion of breast cancer cells (35). It remains to be determined whether AnxA2-receptors play a role in the observed effects of progastrin.

Activation of both NF-κB and β-catenin was required for achieving maximal growth effect of autocrine progastrin (Fig3E). While p65NF-κB activation increased ~2-3-fold in response to autocrine progastrin, COX-2 increased ~6-fold (Fig2A). CD44, amplifies transcriptional activity of p65/β-catenin, by up-regulating acetyl-transferase activity of p300, which acetylates β-catenin/p65NF-κB (36, Supplementary Fig3). Thus, progastrin-mediated nuclear translocation of NF-κB/β-catenin, resulting in up-regulation of CD44 (Figs3A, B), may enhance transcriptional activity of NF-κB/β-catenin, thus amplifying COX-2 expression. Similarly, in colorectal-cancer cells, β-catenin activation in response to autocrine progastrin, up-regulated stem/progenitor cell markers (CD133/CD44) (16), as well as Jagged1 (Notch-ligand) (37, Supplementary Fig3).

Accumulating evidence confirms a critical role of activated p65NF-κB in mediating direct growth effects of progastrin on target cells (7,13,25,38, current-studies). Elevated activation/expression of NF-κB/COX-2 is observed in aggressive colorectal-cancers (39), which also express progastrins (1,2), providing further support for a central role for activated NF-κB, downstream of autocrine-progastrin, in cancer growth. Progastrin also up-regulates β-catenin in colon-cancer-cells, HEK-293-cells, and proximal-colonic-crypts (13,37,40, current-studies). Results of our previous in vivo studies suggest that β-catenin activation may be downstream of activated p65NF-κB (12). Our current in vitro studies confirm that β-catenin activation is downstream of NF-κB (Figs4A, B). However, down-regulation of β-catenin had no effect on levels of activated p65 (Figs4C, D). Thus, we demonstrate for the first time that while β-catenin activation is downstream of activated NF- κB, p65 activation is independent of β-catenin, in response to direct in vitro stimulation with progastrin (Supplementary Fig3).

Cross-talk between IKKα/β/NF-κB and Wnt signaling pathways has been reported by several investigators (41–43). Activated-IKKα blocks both canonical and non-canonical degradation of β-catenin (44). During morphogenesis of hair follicles, NF-κB directly up-regulates Wnt10b (45, Supplementary Fig3). Wnt5a promoter has conserved NF-κB binding sites and its expression is up-regulated by activated-NF-κB and other signaling pathways (46), resulting in activation of β-catenin. Our previous in vivo studies suggested that down-regulation of IKKα/β/NF-κB results in Tyr-phosphorylation of GSK3β (and hence de-activation of GSK3β), which can potentially activate β-catenin (13, Supplementary Fig3). It remains to be determined whether Tyr-phosphorylation of GSK3β is down-regulated by Wnt10b/Wnt5a, in response to PG-activated NF-κB.

DCAMKL+1 (double-cortin and CAM-kinase-like1) is believed to be a marker for quiescent stem cells within intestinal crypts (47,48). In progastrin over-expressing hGAS mice, a significant increase in DCAMKL+1 expressing colonic crypt cells was reported (11). In the current study, we suggest the novel possibility that AnxA2 expression is required for measuring a significant increase in the cell-numbers and relative-levels of DCAMKL+1 expression in direct response to progastrin stimulation, in vitro and in vivo. It remains to be determined whether DCAMKL+1 up-regulation in response to progastrin is mediated via NF-κB and/or β-catenin signaling pathways.

In summary, results of the current studies strongly suggest that AnxA2 expression is required for mediating activation of both p65NF-κB and β-catenin in vitro and in vivo, and that both transcriptional factors are required for observing maximal growth effects of progastrin. Additionally, we demonstrate for the first time that AnxA2 expression is required for progastrin-mediated up-regulation of stem/progenitor cell markers, DCAMKL+1 and CD44, in vitro and in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Fig1 – Effect of exogenous progastrin on cell proliferation and activation of NF-κB and β-catenin in HEK-293 cells. (A). The growth response of HEK-293 cells, in culture, was examined in response to the indicated doses of progastrin, using an MTT assay as described in Methods. Each bar represents data from 6 replicate measurements from a representative of a total of 3 experiments. (B, C). In panel B, wtHEK-293 cells, in culture, were treated with indicated concentrations of progastrin for 3h (based on results in C). For data presented in panel C, cells were treated with 10nM progastrin for the indicated time periods. Relative levels of activated NF-κB were measured in an in vitro DNA binding assay in the nuclear extracts of the treated cells, as described in Methods. Each bar represents data from 3 separate dishes and is representative of 3 experiments. (D). HEK-293 cells were transfected with either wt reporter-promoter plasmid (TOPFlash) or mutant plasmid (FOPFlash) for measuring activation of β-catenin promoter, as described in Methods. After 24h of transfection, cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of progastrin, and processed for measuring relative levels of luciferase after 48h of progastrin treatment. Each bar represents mean ± SEM of 3 separate measurements from 1 experiment, and is representative of 3 similar experiments. *=p<0.05 vs control levels measured in the absence of progastrin (PG).

Supplementary Fig2. Autocrine progastrin up-regulates relative levels of DCAMKL+1/CD44 in HEK-mGAS andHEK-C cells. HEK-C and HEK-mGAS cells growing on coverslips were stained for the indicated stem cell markers, as described in the legend of Fig1D. The bright green fluorescence in each case represents specific antibody binding to either CD44 or DCAMKL+1 as shown.

Supplementary Fig3. Diagrammatic representation of cellular/intracellular mechanisms mediating growth response of target cells to exogenous or autocrine progastrin: role of ANXA2. Based on our previous and current findings, the role of ANXA2 and several signaling molecules/transcription factors/target proteins in mediating the growth effects of endocrine/autocrine progastrin peptides is presented as a diagrammatic model. Relevant data from other investigators is also presented. Reference numbers or figure numbers (current studies) which provide evidence for a role of the indicated molecules (pathways) are shown in parentheses. Dashed lines= speculative pathway. Solid lines = experimentally shown in the indicated figure/reference. T lines = Inhibition of the indicated pathway.

Supplementary Fig4. Annexin A2 expression is required for measuring an increase in the lengths of isolated colonic crypts in response to progastrin in vivo. Using FVB/N mice, we had previously reported that colonic crypts from the proximal colons of the mice were extremely responsive to the growth promoting effects of progastrin (12). However, for reasons unknown, the C57Bl/6J mice do not develop tumors in the proximal colon in response to azoxymethane (Cobb et al, Gastroenterology 2002), but mainly develop tumors in the middle and distal portions of the colon. In initial studies, we therefore confirmed growth effects of progastrin on the mid-colons of the C57Bl/6J (C57) mice. For these studies the colons were processed for the preparation of isolated intact colonic crypts, as described previously (12,13). In the next set of experiments we examined the growth promoting effects of 10nM PG on the colonic crypts of ANXA2+/+ and ANXA2− /− mice, as described in the Methods section. Because the mid-colons of the ANXA2+/+ mice were most responsive to the growth effects of PG, we chose to measure the lengths of isolated colonic crypts only from the mid-colons of the mice, and representative images of the isolated colonic crypts are presented from the four groups of mice. Data from all the mice in the four groups are presented as bar graphs in Fig5C.

Supplementary Fig5. AnxA2 expression is required for stimulatory effect of progastrin on CD44/DCAMKL+1 expression in colonic crypts. AnxA2+/+/ AnxA2− /− mice were treated with either saline (0nM) or 10nM-rhPG. Colons were removed at the time of sacrifice and processed for making tissue sections, as described in Methods. Mouse colon sections from the indicated 4 groups of mice were processed for immunofluorescence staining with either anti-DCAMKL+1-IgG (green) or anti-CD44-IgG (red). Representative images from stained sections of colons from indicated mice are presented at 20x magnification. Enlarged images (60x) from a representative portion of each section, are also presented in Fig6C. Red and green staining shows cells staining for CD44 and DCAMKL+1, respectively, along the lengths of the colonic crypts, at 20x. DAPI shows the nucleated cells within the viewing field. As can be seen, the relative staining for CD44 and DCAMKL+1 per cell was highest in progastrin treated ANXA2+/+ mice, compared to all other groups. The total number of cells, positive for the two stem/progenitor cell markers, within a viewing field were also the highest in ANXA2+/+ mice, compared to all other groups. The quantitative analysis of the data, obtained from these images, are presented in Fig6. A curious finding was that while down-regulation of ANXA2 in vitro in HEK-mGAS cells did not completely attenuate the increase in CD44 levels in response to autocrine PG (Fig3C), the loss of ANXA2 expression in ANXA2− /− mice resulted in complete attenuation of PG stimulated increase in CD44 levels, in vivo. The differences in the relative effects on CD44 levels in vitro versus in vivo may reflect the fact that CD44 expression was increased robustly in vitro in HEK-mGAS cells (Figs3B, C but was not increased to the same extent in ANXA2+/+ mice in response to PG (Figs6C, D).

Acknowledgments

Grant Support and Acknowledgements- This work was supported by NIH grants CA97959 and CA114264 to PS; HL 042493, HL 046403, and HL 090895 to KH. The technical help of Carrie Maxwell and secretarial assistance of Cheryl Simmons are acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- Abs

antibodies

- AnxA2

annexin A2

- ANXA2− /− mice

C57Bl/J6 mice knocked down for the expression of annexin A2

- CCK1R and CCK2R

cholecystokinin type 1 and type 2 receptors, respectively

- DCAMKL+1

double cortin CAM kinase-like 1

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- HEK-C

wtHEK-293 cells expressing control empty vector

- HEK-mGAS mice

HEK-293 clones overexpressing mutant gastrin gene resulting in expression of full-length progastrin

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- p65

p65NF-κB

- PG

progastrin

- hPG

human progastrin

- rhPG

recombinant human progastrin

- siRNA

small inhibitory double stranded RNA oligonucleotides

- ANXA2+/+ mice

wild type C57Bl/J6 mice

- >*

significantly higher values between the indicated groups as presented in Abstract

Footnotes

RS and CK generated the samples from the in vivo studies; SS generated the data from the in vitro and in vivo studies; PS directed and designed the experiments; KH generated the annexin A2-KO mice and helped PS write the manuscript.

DISCLOSURE: None of the authors have any conflict of interest with any entity related to the data presented in here.

References

- 1.Rengifo-Cam W, Singh P. Role of progastrins and gastrins and their receptors in GI and pancreatic cancers: targets for treatment. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:2345–2358. doi: 10.2174/1381612043383999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grabowska AM, Watson SA. Role of gastrin peptides in carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2007;257:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldwin GS, Hollande F, Yang Z, et al. Biologically active recombinant human progastrin contains a tightly bound calcium ion. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7791–7796. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009985200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh P, Lu X, Cobb S, et al. Progastrin1–80 stimulates growth of intestinal epithelial cells in vitro via high-affinity binding sites. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:G328–G339. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00351.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang TC, Koh TJ, Varro A, et al. Processing and proliferative effects of human progastrin in transgenic mice. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1918–1929. doi: 10.1172/JCI118993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu H, Owlia A, Singh P. Precursor peptide progastrin reduces apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells and upregulates cytochrome c oxidase Vb levels and synthesis of ATP. Am J Physiol. 2003;285:G1097–G1110. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00216.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rengifo-Cam W, Umar S, Sarkar S, et al. Antiapoptotic effects of progastrin on pancreatic cancer cells are mediated by sustained activation of nuclear-factor-{kappa}B. Can Res. 2007;67:7266–7274. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cobb S, Wood T, Ceci J, et al. Intestinal expression of mutant and wild-type progastrin significantly increases colon-carcinogenesis in response to azoxymethane in transgenic mice. Cancer. 2004;100:1311–1123. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh P, Velasco M, Given R, et al. Progastrin expression predisposes mice to colon carcinomas and adenomas in response to a chemical carcinogen. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:162–171. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.8527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ottewell PD, Varro A, Dockray GJ, et al. COOH-terminal 26-amino acid residues of progastrin are sufficient for stimulation of mitosis in murine colonic epithelium in vivo. Am J Physiol. 2005;288:G541–G549. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00268.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin G, Ramanathan V, Quante M, et al. Inactivating cholecystokinin-2 receptor inhibits progastrin-dependent colonic crypt fission, proliferation, and colorectal cancer in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2691–26701. doi: 10.1172/JCI38918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Umar S, Sarkar S, Cowey S, et al. Activation of NF-kappaB is required for mediating proliferative and antiapoptotic effects of progastrin on proximal colonic crypts of mice, in vivo. Oncogene. 2008;8:5599–5611. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Umar S, Sarkar S, Wang Y, Singh P. Functional cross-talk between beta-catenin and NFkappaB signaling pathways in colonic crypts of mice in response to progastrin. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:22274–22284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.020941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stepan VM, Krametter DF, Matsushima M, et al. Glycine-extended gastrin regulates HEK cell growth. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:R572–R581. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.2.R572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh P, Wu H, Clark C, et al. AnnexinII binds progastrin and gastrin-like peptides, and mediates growth factor effects of autocrine and exogenous gastrins on colon cancer and intestinal-epithelial-cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:425–440. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrand A, Sandrin MS, Shulkes A, Baldwin GS. Expression of gastrin precursors by CD133-positive colorectal cancer cells is crucial for tumour growth. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:477–488. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh P, Sarkar S, Umar S, et al. Insulin-like growth factors are more effective than progastrin in reversing proapoptotic effects of curcumin: critical role of p38MAPK. Am J Physiol. 2010;298:G551–G562. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00497.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh P, Owlia A, Espeijo R, et al. Novel gastrin receptors mediate mitogenic effects of gastrin and processing intermediates of gastrin on Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts. Absence of detectable cholecystokinin (CCK)-A and CCK-B receptors. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8429–8438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacovina AT, Deora AB, Ling Q, et al. Homocysteine inhibits neoangiogenesis in mice through blockade of annexin A2-dependent fibrinolysis. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3384–3394. doi: 10.1172/JCI39591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beales IL, Ogunwobi O. Glycine-extended gastrin inhibits apoptosis in Barrett’s oesophageal and oesophageal adenocarcinoma cells through JAK2/STAT3 activation. J Mol Endocrinol. 2009;42:305–318. doi: 10.1677/JME-08-0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubeykovskiy A, Nguyen T, Dubeykovskaya Z, et al. Flow cytometric detection of progastrin interaction with gastrointestinal cells. Regul Pept. 2008;151:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Przemeck SM, Varro A, Berry D, et al. Hypergastrinemia increases gastric epithelial susceptibility to apoptosis. Regul Pept. 2008;146:147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chicone L, Narayan S, Townsend CM, Jr, et al. The presence of a 33–40 KDa gastrin binding protein on human and mouse colon cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;164:512–519. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91749-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song DH, Rana B, Wolfe JR, et al. Gastrin-induced gastric adenocarcinoma growth is mediated through cyclin D1. Am J Physiol. 2003;285:G217–G222. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00516.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sebens Müerköster S, Rausch AV, Isberner A, et al. Apoptosis-inducing effect of gastrin on colorectal cancer cells relates to an increased IEX-1 expression mediating NF-kappaB inhibition. Oncogene. 2008;27:1122–1134. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cui G, Takaishi S, Ai W, et al. Gastrin-induced apoptosis contributes to carcinogenesis in the stomach. Lab Invest. 2006;86:1037–1051. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ortiz-Zapater E, Peiro S, et al. Tissue plasminogen activator induces pancreatic cancer cell proliferation by non-catalytic mechanism that requires extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation through epidermal growth factor receptor and annexin A2. American J Pathology. 2007;170(5):1573–1584. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diaz VM, Hurtado M, et al. Specific interaction of tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA) with annexinII on the membrane of pancreatic cancer cells activates plasminogen and promotes invasion in vitro. Gut. 2004;53(7):993–1000. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.026831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma MC, Sharma M. Role of annexinII in angiogenesis and tumor progression: a potential therapeutic target. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;130:3568–3575. doi: 10.2174/138161207782794167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kesavan K, Ratliff J, Johnson EW, et al. AnnexinA2 is a molecular target for TM601, a peptide with tumor-targeting and anti-angiogenic effects. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:4366–4374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.066092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh P. Role of Annexin-II in GI cancers: interaction with gastrins/progastrins. Cancer Lett. 2007;252:19–35. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inokuchi J, Narula N, Yee DS, et al. AnnexinA2 positively contributes to malignant phenotype and secretion of IL-6 in DU145 prostate cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:68–74. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu G, Maeda H, Reddy SV, et al. Cloning and characterization of annexin-II receptor on human marrow stromal cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30542–30550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607072200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shiozawa Y, Havens AM, Jung Y, et al. AnnexinII/annexinII-receptor axis regulates adhesion, migration, homing, and growth of prostate cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105:370–380. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ling Q, Jacovina AT, Deora A, et al. AnnexinII regulates fibrin homeostasis and neoangiogenesis in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:38–48. doi: 10.1172/JCI200419684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bourguignon LY, Xia W, Wong G. Hyaluronan-CD44 interaction with protein kinase C(epsilon) promotes oncogenic signaling by stem cell marker Nanog and the Production of microRNA-21, leading to down-regulation of tumor suppressor protein PDCD4, anti-apoptosis, and chemotherapy resistance in breast tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:2657–2671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.027466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pannequin J, Bonnans C, Delaunay N, et al. The wnt target jagged-1 mediates activation of notch signaling by progastrin in human colorectal cancer cells. Can Res. 2009;69:6065–6073. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Subramaniam D, Ramalingam S, May R, et al. Gastrin-mediated interleukin-8 and cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression: differential transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1070–1082. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pancione M, Forte N, Sabatino L, et al. Reduced beta-catenin and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma expression levels are associated with colorectal cancer metastatic progression: correlation with tumor-associated macrophages, cyclooxygenase 2, and patient outcome. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:714–725. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pannequin J, Delaunay N, Buchert MF, et al. Beta-catenin/Tcf-4 inhibition after progastrin targeting reduces growth and drives differentiation of intestinal tumors. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1554–1568. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Albanese C, Wu K, D’Amico M, et al. IKKalpha regulates mitogenic signaling through transcriptional induction of cyclin D1 via Tcf. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:585–599. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-06-0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cho HH, Song JS, Yu JM, et al. Differential effect of NF-kappaB activity on beta-catenin/Tcf pathway in various cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:616–622. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lamberti C, Lin KM, Yamamoto Y, et al. Regulation of beta-catenin function by the IkappaB kinases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:42276–42286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104227200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carayol N, Wang CY. IKKalpha stabilizes cytosolic beta-catenin by inhibiting both canonical and non-canonical degradation pathways. Cell Signal. 2006;18:1941–1946. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Y, Tomann P, Andl T, et al. Reciprocal requirements for EDA/EDAR/NF-kappaB and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathways in hair follicle induction. Dev Cell. 2009;17:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katoh M, Katoh M. Integrative genomic analyses of CXCR4: transcriptional regulation of CXCR4 based on TGFbeta, Nodal, Activin signaling and POU5F1, FOXA2, FOXC2, FOXH1, SOX17, and GFI1 transcription factors. Int J Mol Med. 2009;23:763–769. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.May R, Riehl TE, Hunt C, et al. Identification of a Novel Putative Gastrointestinal Stem Cell and Adenoma stem cell marker, Doublecortin and CaM Kinase-Like-1, following Radiation Injury and in Adenomatous Polyposis Coli/Multiple Intestinal Neoplasia Mice. Stem Cells. 2008;26:630–637. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.May R, Sureban SM, Hoang N, et al. Doublecortin and CaM kinase-like-1 and leucine-rich-repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor mark quiescent and cycling intestinal stem cells, respectively. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2571–2579. doi: 10.1002/stem.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig1 – Effect of exogenous progastrin on cell proliferation and activation of NF-κB and β-catenin in HEK-293 cells. (A). The growth response of HEK-293 cells, in culture, was examined in response to the indicated doses of progastrin, using an MTT assay as described in Methods. Each bar represents data from 6 replicate measurements from a representative of a total of 3 experiments. (B, C). In panel B, wtHEK-293 cells, in culture, were treated with indicated concentrations of progastrin for 3h (based on results in C). For data presented in panel C, cells were treated with 10nM progastrin for the indicated time periods. Relative levels of activated NF-κB were measured in an in vitro DNA binding assay in the nuclear extracts of the treated cells, as described in Methods. Each bar represents data from 3 separate dishes and is representative of 3 experiments. (D). HEK-293 cells were transfected with either wt reporter-promoter plasmid (TOPFlash) or mutant plasmid (FOPFlash) for measuring activation of β-catenin promoter, as described in Methods. After 24h of transfection, cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of progastrin, and processed for measuring relative levels of luciferase after 48h of progastrin treatment. Each bar represents mean ± SEM of 3 separate measurements from 1 experiment, and is representative of 3 similar experiments. *=p<0.05 vs control levels measured in the absence of progastrin (PG).

Supplementary Fig2. Autocrine progastrin up-regulates relative levels of DCAMKL+1/CD44 in HEK-mGAS andHEK-C cells. HEK-C and HEK-mGAS cells growing on coverslips were stained for the indicated stem cell markers, as described in the legend of Fig1D. The bright green fluorescence in each case represents specific antibody binding to either CD44 or DCAMKL+1 as shown.

Supplementary Fig3. Diagrammatic representation of cellular/intracellular mechanisms mediating growth response of target cells to exogenous or autocrine progastrin: role of ANXA2. Based on our previous and current findings, the role of ANXA2 and several signaling molecules/transcription factors/target proteins in mediating the growth effects of endocrine/autocrine progastrin peptides is presented as a diagrammatic model. Relevant data from other investigators is also presented. Reference numbers or figure numbers (current studies) which provide evidence for a role of the indicated molecules (pathways) are shown in parentheses. Dashed lines= speculative pathway. Solid lines = experimentally shown in the indicated figure/reference. T lines = Inhibition of the indicated pathway.

Supplementary Fig4. Annexin A2 expression is required for measuring an increase in the lengths of isolated colonic crypts in response to progastrin in vivo. Using FVB/N mice, we had previously reported that colonic crypts from the proximal colons of the mice were extremely responsive to the growth promoting effects of progastrin (12). However, for reasons unknown, the C57Bl/6J mice do not develop tumors in the proximal colon in response to azoxymethane (Cobb et al, Gastroenterology 2002), but mainly develop tumors in the middle and distal portions of the colon. In initial studies, we therefore confirmed growth effects of progastrin on the mid-colons of the C57Bl/6J (C57) mice. For these studies the colons were processed for the preparation of isolated intact colonic crypts, as described previously (12,13). In the next set of experiments we examined the growth promoting effects of 10nM PG on the colonic crypts of ANXA2+/+ and ANXA2− /− mice, as described in the Methods section. Because the mid-colons of the ANXA2+/+ mice were most responsive to the growth effects of PG, we chose to measure the lengths of isolated colonic crypts only from the mid-colons of the mice, and representative images of the isolated colonic crypts are presented from the four groups of mice. Data from all the mice in the four groups are presented as bar graphs in Fig5C.

Supplementary Fig5. AnxA2 expression is required for stimulatory effect of progastrin on CD44/DCAMKL+1 expression in colonic crypts. AnxA2+/+/ AnxA2− /− mice were treated with either saline (0nM) or 10nM-rhPG. Colons were removed at the time of sacrifice and processed for making tissue sections, as described in Methods. Mouse colon sections from the indicated 4 groups of mice were processed for immunofluorescence staining with either anti-DCAMKL+1-IgG (green) or anti-CD44-IgG (red). Representative images from stained sections of colons from indicated mice are presented at 20x magnification. Enlarged images (60x) from a representative portion of each section, are also presented in Fig6C. Red and green staining shows cells staining for CD44 and DCAMKL+1, respectively, along the lengths of the colonic crypts, at 20x. DAPI shows the nucleated cells within the viewing field. As can be seen, the relative staining for CD44 and DCAMKL+1 per cell was highest in progastrin treated ANXA2+/+ mice, compared to all other groups. The total number of cells, positive for the two stem/progenitor cell markers, within a viewing field were also the highest in ANXA2+/+ mice, compared to all other groups. The quantitative analysis of the data, obtained from these images, are presented in Fig6. A curious finding was that while down-regulation of ANXA2 in vitro in HEK-mGAS cells did not completely attenuate the increase in CD44 levels in response to autocrine PG (Fig3C), the loss of ANXA2 expression in ANXA2− /− mice resulted in complete attenuation of PG stimulated increase in CD44 levels, in vivo. The differences in the relative effects on CD44 levels in vitro versus in vivo may reflect the fact that CD44 expression was increased robustly in vitro in HEK-mGAS cells (Figs3B, C but was not increased to the same extent in ANXA2+/+ mice in response to PG (Figs6C, D).