Abstract

Background

Female sex workers' (FSWs') use of alcohol, a known disinhibitor to risk behavior, has been largely understudied. Knowledge of how various sex work venues influence FSW's alcohol consumption before engaging in commercial sex is even rarer. Our analysis identifies those factors across three types of sex-work venues that predict alcohol use among FSWs prior to paid sexual intercourse with clients. Our data were collected through structured interviews with FSWs engaging in commercial sex in Senggigi Beach, Lombok Island in the eastern Indonesian province of West Nusa Tenggara.

Methods

Employing a cross sectional and multilevel design, three categories of venues where FSWs meet clients in Senggigi were sampled: (1) discotheques and bars (freelance), (2) brothels, and (3) recreational enterprises such as karaoke establishments and massage parlors. The sample consisted of 115 women “nested” within 16 sex work venues. The FSWs reported on 326 clients interactions.

Results

Results show that FSWs consumed alcohol before commercial sex with 157 (48%) of the 326 clients interactions. Alcohol use varied by differences in HIV policies and services offered at the sex work venue, the FSW's educational level and age, and client characteristics.

Conclusion

Alcohol use is common prior to sexual intercourse among FSWs and their clients in Senggigi, and the venue where FSWs meet their clients influences the women's alcohol use. Freelancers were likelier to use alcohol than those who work at brothels and recreational enterprises. Given the recognized links between alcohol use prior to sex and high risk behavior, HIV prevention programs that discourage alcohol use should be introduced to both women who engage in commercial sex and also sex-work venue managers, owners, and clients.

Keywords: Sex work, venue, alcohol use, HIV, Indonesia, multilevel analysis

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol's contribution to the global HIV epidemic by encouraging high risk behavior, especially among high risk groups, has long been acknowledged (Brown et al., 2006; Madhivanan et al., 2005; Raj et al., 2006). In this regard, research worldwide indicates that alcohol use predicts increased HIV related-risk behavior for female sex workers (FSWs) via increased risk of unprotected sex with their clients (Plant, 1990; Plant et al, 1990; Chersich et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2005). Meanwhile, several studies of HIV risk behavior among FSWs document the importance of understanding the dynamic relationship between the personal attributes of the women and the social environment in which they engage in risky behavior (Brents & Hausbeck, 2005; Ford et al., 2002; MAP, 2005; Nguyen et al., 2000). Yet, little research attention has focused on identifying the potential link between FSWs' personal characteristics and the influence of their sex work environment in determining alcohol use as a high-risk behavior.

This study investigates predictors of alcohol use among FSWs engaged in commercial sex at three types of sex work venues in Senggigi, Indonesia prior to paid intercourse with their clients. Senggigi, which is located in the eastern Indonesian province of West Nusa Tenggara (NTB), stretches out along 10 kilometers of beachfront. As the most developed tourism enclave in the NTB province, Senggigi attracts a constant flow of foreign and domestic tourists. Rural youth from the local countryside also are lured to the area by the prospect of finding a job in the tourist economy or the possibility of greater social freedom (Bennett, 2000). A well-established but illegal sex industry contributes an unknown number of dollars annually to Senggigi's local economy, a characteristics that has been true for much of Indonesia's major leisure and tourist destinations since the country's colonial days (Lim, 1998).

Indonesia in general has seen a sharp increase in HIV among FSW in recent years (MOH et al., 2008; MAP, 2004; Riono & Jazant, 2004). In addressing this component of the epidemic, public health research on FSWs in Indonesia has focused primarily on the role of individual risk-behavior in the spread of HIV. This study extends this research by examining how FSW's personal characteristics under the influence of differing sex-work environments predict the consumption of alcohol prior to sex with their clients.

Over the last decade, the concept of “risk environment” has emerged as an increasingly important theoretical approach to understanding HIV risk and/or protective behavior. Investigations of the role of social environment in promoting risky behavior include settings where drugs are used (Klein & Levy, 2003; Ouellet et al., 1991; Rhodes, 2002; Tempalski & McQuie, 2009), bathhouses as high-risk settings among men who have sex with men (Binson & Woods, 2003), and low-income senior housing complexes among older minority adults (Schensul, Levy, & Disch, 2003). A limited literature has identified several characteristics of sex work environments associated with risky behavior, including monetary concerns and the lack of support for risk reduction from owners-managers, customers and peers (Morisky et al., 1998; Morisky et al., 2002; Morisky et al., 2005; Morisky et al., 2006; Outwater et al., 2000; Kerrigan et al., 2003). A study of FSWs in the Philippines concludes that commercial sex work establishments serve as the situational context for alcohol consumption and that sexual risk behaviors occur with greater frequency among FSWs who use alcohol before commercial sex (Chiao et al., 2006).

In Indonesia, FSWs meet their clients in different social milieus that include red-light areas, brothels, on the street, and recreational enterprises (e.g. karaoke establishments, massage parlors, and so on) (Riono & Jazant, 2004; Fajans, Ford, & Wirawan, 1994; Ford, Wirawan, & Fajans, 1995; Ford, Wirawan, & Fajans, 1998; Ford et al., 2000; Ford & Wirawan, 2005; Hugo, 2001; Joesoef et al., 1997; Joesoef et al., 2000; Sedyaningsih-Mamahit, 1999; Thorpe et al., 1997). FSWs working within these settings are subject to differing external control over their sex work activities according to the type of venues where they solicit clients. “Rumah bordel (unofficial brothels)” operate outside of government administration and typically consist of single dwellings managed by a brothel owner who receives a room rental fee from the FSWs but does not necessarily manage their client-related activities. In contrast, recreational enterprises such as karaoke establishments and massage parlors maintain contractual agreements with the women to provide massage and/or companionship services for male customers including paid sex if the woman agrees (Lim, 1998; Safika, 2009; Surtees, 2004). These women are subject to varying managerial rules depending on the particular establishment. Meanwhile, no specific regulations govern or restrict freelancers from meeting their clients at discotheques and bars where their presence may help to boost customer patronage and alcohol purchases. Establishment managers or owners have no direct commercial agreement with the FSWs other than to allow or deny them access as customers (Safika, 2009).

Ethnographic research in the Senggigi area of Lombok, Indonesia showed that alcohol is commonly consumed across all of these venues (Safika, 2009). For example, freelance FSWs who seek clients at discotheques and bars typically congregate and consume alcohol as a group while waiting for potential clients at the establishment's entrance. Similarly, in addition to possibly accruing money through commercial sex, women who work in karaoke establishments are paid by the venue's owner to sing and drink with clients to increase establishment profits through alcohol sales (Safika, 2009).

We hypothesize in this analysis that alcohol use varies by sex work venues and by individual FSWs across sex work venues. We also hypothesize that alcohol use is more likely to occur: a) among freelance sex workers, b) within sex work venues that do not implement HIV related policies, and c) within establishments run by owners or managers who were non-supportive of FSW health and well-being. We further posit that alcohol use is more likely to occur among FSWs who have lesser knowledge of HIV than their counterparts with greater knowledge and also to vary by the type of client with whom the FSWs engage in paid sex.

METHODS

Study design and procedures

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Office for the Protection of Research Subjects, University of Illinois at Chicago. Local approval also obtained from the Regional Development Planning Agency, Office of Research, West Nusa Tenggara.

A cross-sectional design based on venue-based sampling was used to identify and recruit FSWs in Senggigi on Lombok Island in the eastern Indonesian province of West Nusa Tenggara. Outreach workers from two local nongovernment agencies helped the senior author to map and gain access to the range of sex establishments and venues in the Senggigi commercial sex area. Twenty six sex work venues initially were identified and subsequently categorized into one of three venue types: (1) discotheques and bars (freelance), (2) brothels, and (3) recreational enterprises such as karaoke establishments and massage parlors. With the exception of six freelance locations where approval for study recruitment was unnecessary, a manager's or owner's permission was needed to approach and recruit potential participants for the study. All five brothels, eight out of ten massage parlors, and three out of five karaoke bars granted permission.

To be eligible for the study, participants had to be: (a) female, (b) 18 years of age or older, (c) solicit clients at one of the following locations: brothels, freelance locations, or recreational enterprises (massage parlors or karaoke bars) in the Senggigi area, and (d) willing to provide informed consent to participate in the study. Overall, 151 women across 22 venues met these criteria. In obtaining informed consent, prospective participants were assured that enrollment in the study was entirely voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time without penalty. Using a structured questionnaire, the senior author interviewed the participants face-to-face about their personal characteristics, their sex work venue, sexual behavior, and alcohol consumption before sex with their three most recent clients. To protect confidentiality, code numbers were used instead of names or other personal identifiers, and all completed interviews and other data were kept in a locked cabinet at a location 20 kilometers from the study site to which only the senior author had access.

Measures

The dependent variable was a dichotomous indicator of FSW alcohol use before sex that was measured by asking respondents about each client, “Did you drink alcohol with [client] before sex?” Independent variables were measured at three levels: sex work venue, personal (characteristics of the FSW), and client.

Venue-level variables included supportive versus non-supportive management style as reported by the FSWs and defined by whether or not a venue's owners or managers appeared to emphasize profit over the health and welfare of the FSWs who worked there. A second venue-level variable assessed each establishment's HIV risk-reduction policies and services as measured by the FSWs' reports of whether or not it provided free condoms, offered one or more HIV educational sessions for the women, and/or gave permission for them to attend HIV education sessions conducted by local non-governmental organizations.

Personal-level variables included each FSW's demographic characteristics and knowledge about HIV transmission. Demographic variables were collected and coded as marital status (ever versus never married), educational achievement (less than or equal to six years of elementary education versus junior high school or higher), place of origin (Lombok versus non-Lombok), and age (less than or equal to 25 years of age versus older). Knowledge about HIV transmission was measured based on the total number of correct responses to a series of 14 questions that were adopted from previous study of FSWs in Indonesia (Ford et al., 2002).

Client-level variables were collected and coded as: 1) client type (new versus regular), 2) origin of the client (domestic/local Indonesian versus foreign), and 3) client age (less than versus more than 35 years).

Although many studies of FSW risk behavior include condom use as a variable in their analysis, we have chosen not to do so here. Our focus is on identifying the predictors of alcohol use among FSWs prior to paid sex, not the subsequent consequences of that use during paid sex. We recognize the importance of examining FSWs' alcohol consumption as a possible factor in explaining unprotected sexual intercourse, but such an analysis is best undertaken with condom use as the dependent variable and alcohol consumption prior to engaging in paid sex as one of several key explanatory variables. We have undertaken such an analysis elsewhere (Safika, 2009).

Analysis

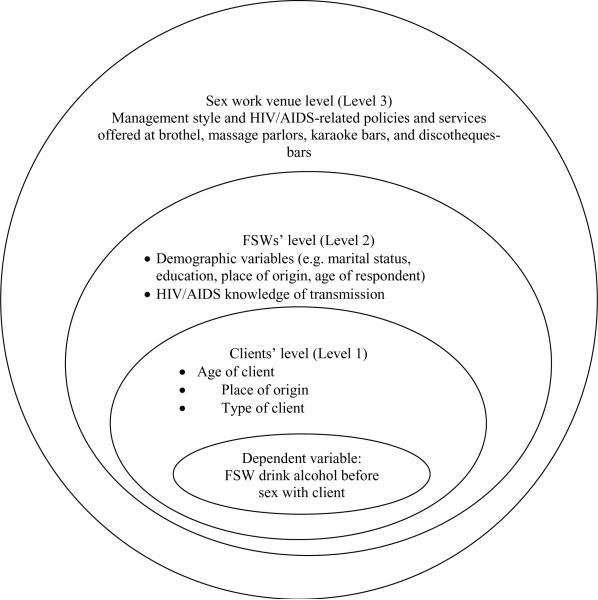

A multilevel model was used to examine the relationship between sex work venue and FSWs' alcohol use. In this study's design, clients are nested within FSWs, and FSWs are nested within sex work venue. Thus, sex work venue characteristics at the highest level, as well as FSW and client level variables (at the second and lowest levels, respectively), are predicted to influence alcohol use among FSWs (at the second level). Figure 1 illustrates the set of predictors at each level that potentially influence FSWs' alcohol use.

Figure 1.

Multilevel model of the influence of sex work venue, FSW and client-level variables on FSW's alcohol use

A random intercept three-level Hierarchical Generalized Linear Model (HGLM) model using HLM 6 (Raudenbush et al., 2002) was estimated to examine the influence of sex work venue on FSW's alcohol use.

The level-1 (client's predictors) structural model was:

Where:

ηijk=the logit odds of the FSW j alcohol use with client i at the sex work venue k;

πojk=is the intercept for FSW j in sex work venue k; and

π1 to 3jk =are client level predictors of FSWs' alcohol use

At level-2, πojk is modeled as a function of the level-2 predictors. The other level-1 coefficients, πpjk, are viewed as fixed, nonrandomly varying:

Where:

βook=is the intercept for sex work venue k in modeling the FSW effect πojk;

βo1 to 5k=are FSW level predictors; and

rojk=is a level-1 and 2 random effect that represents the variation of alcohol use between FSWs.

At level-3, we model βook as a function of the level-3 predictors. The other level-2 coefficients,

βpk, are viewed as fixed, nonrandomly varying:

β00k=y000+y001(management_stylek)+y002(HIV_related_policies_servicesk)+U00k

Where:

γooo=is the intercept term in the sex work venue-level model for βook;

γo1 to 2=are sex work venue level predictors; and

υook=is a level-3 random effect that represents the variation of alcohol use between sex work.

RESULTS

Of the 151 women enrolled in this study, 115 (76%) admitted during the interview that they exchanged sex for money with at least one paying client in the last three months. These 115 nested within 16 sex work venues. This number included 47 women who sought clients at discotheques and bars; 39 whose sex work was brothel-based; and 29 who worked at recreational enterprises (karaoke bars and massage parlors).

Most of the FSWs (92%) reported having had at least three recent clients within the last three months, with the remaining 9 FSWs (8%) having 1 to 2 recent clients. In total, 330 client interactions were available for analysis. Due to missing values at the client level, the final sample represented 326 clients (Level-1) nested within 115 FSWs (Level-2) and 16 sex work venues (Level-3). Table 1 summarizes information for client, FSW and sex work venue-level variables.

Table 1.

Summary Information for Client, FSWs and Sex Work Venue-Level Variables

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1. Clients (N=326) | ||

| FSW drank alcohol before sex with client | ||

| Yes | 157 | 48 |

| No | 169 | 52 |

| Type of client | ||

| New | 180 | 55 |

| Regular | 146 | 45 |

| Origin of client | ||

| Domestic/Indonesian | 249 | 76 |

| Foreign clients | 77 | 24 |

| Age of the client | ||

| <= 35 years | 191 | 59 |

| 36 years and older) | 135 | 41 |

| Level II. FSWs (N=115) | ||

| Marital status | ||

| Ever married | 85 | 74 |

| Never married | 30 | 26 |

| Education level | ||

| ≤Elementary school | 56 | 49 |

| Junior high school and higher | 59 | 51 |

| Place of origin | ||

| Lombok | 66 | 57 |

| Other | 49 | 43 |

| Age of respondent | ||

| 26 years and more | 63 | 55 |

| <=25 years | 52 | 45 |

| HIV knowledge of transmission | ||

| Mean: 7.4 | ||

| Maximum score: 14 | ||

| Level III Sex work venue (N=16) | ||

| Management style | ||

| Supervised by non-supportive venue | 8 | 50 |

| managers or owners | 8 | 50 |

| No supervision | ||

| HIV/AIDS-related policies and services were offered at the sex work venue | ||

| Yes | 11 | 69 |

| No | 5 | 31 |

As shown in Table 1, slightly more than half (56%) of the participating sex work venues were classified as being supervised by non-supportive venue managers or owners whom the women perceived as being more concerned with profits than ensuring their well-being. Yet, more than two thirds (69%) of the venues were reported as endorsing HIV-related policies and/or access to services.

Of the115 FSWs interviewed, 74% reported being or having been married. More than half were of local origin (57%) and less than 25 years old (55%). Almost half (49%) reported having attained no more than an elementary school education. On average, the women were able to correctly answer just over half of the 14 questions concerning HIV transmission (mean =7.4). The women also reported drinking alcohol prior to paid sex with 157 (48%) of their 326 client interactions. Of the 326 total sexual exchanges, 76% were with local Indonesian as opposed to foreigners and other tourists; 56% with new clients; and 58% with men under age 35.

Table 2 presents the characteristics of FSW's clients. When compared to their brothel and entertainment counterparts, results show that freelancers were more likely to report clients who were younger (<= 35 years) and foreign (p<0.05). They also were more likely to drink alcohol before sex with their clients (p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Characteristics of FSW's client (N=326)

| Frequency (%) | Test statistic for difference between the groups (p-value) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freelance n=139 | Brothel n=116 | Entertainment n=71 | ||

| Age category | ||||

| ≤35 years | 70 (50%) | 91 (78%) | 30 (42%) | χ2(df=2)=30.54 |

| > 36 years | 69 (50%) | 25 (22%) | 41 (58%) | p <0.001 |

| Type of client | ||||

| New | 82 (59%) | 65 (56%) | 33 (46%) | χ2(df=2)=3.02 |

| Regular | 57 (41%) | 51 (44%) | 38 (54%) | p =0.220 |

| Origin of client | ||||

| Domestic/Indonesia | 75 (54%) | 112 (97%) | 62 (87%) | χ2(df=2)=69.62 |

| Foreigner | 64 (46%) | 4 (3%) | 9 (13%) | p <0.001 |

| Alcohol use before sex | 94 (68%) | 35 (30%) | 27 (38%) | χ2(df=2)=39.06 |

| p <0.001 | ||||

Multilevel Analysis

Results using multilevel analysis confirmed that alcohol use did vary by sex venue (χ2= 27.09; p=0.012) and that rates of alcohol consumption prior to sex were higher among freelancers than brothel and entertainment-based FSWs (see Table 2). Significant variability of FSWs personal characteristics within each venue on alcohol use was also found (χ2= 217.48; p=0.000). These findings demonstrated the need for a three-level model that includes predictors relating to the FSWs personal characteristics, clients and sex work venue. Table 3 presents results from a random intercept three-level HGLM that includes all 3 categories of variable predicting FSWs' alcohol use prior to commercial sex.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Generalized Linear Models Evaluating Effects of Client, FSWs and Sex Work Venue Characteristics on Alcohol Use Prior to Sexual Intercourse (N=326)

| Variable | Odd Ratios (OR) | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Client-level predictors | |||

| Type of client (New) | 0.61 | 0.44–0.84 | 0.003 |

| Origin of client (Domestic/local Indonesian) | 1.32 | 0.86–2.02 | 0.074 |

| Age (Younger than 35 years old) | 0.88 | 0.58–1.37 | 0.595 |

| FSW-level predictors | |||

| Marital status (Ever married) | 0.46 | 0.20–1.05 | 0.065 |

| Education level (Less than elementary school) | 0.38 | 0.18–0.80 | 0.012 |

| Place of origin (Lombok) | 1.66 | 0.64–4.36 | 0.297 |

| Age of respondent (Younger than 25 years old) | 0.42 | 0.22–0.80 | 0.010 |

| Knowledge of HIV transmission | 1.00 | 0.90–1.12 | 0.960 |

| Sex work venue-level predictors | |||

| Management style (Supervised by non-supportive venue managers/owners) | 0.72 | 0.12–4.21 | 0.695 |

| HIV/AIDS-related policies and services were offered at the sex work venue (Yes) | 0.34 | 0.11–1.08 | 0.065 |

At the venue level, perceived managerial support and HIV-related policies were examined as possible predictors of alcohol use before paid sex. As shown in Table 3, FSWs' perception of support from venue managers or owners in ensuring their well-being over maximizing establishment profits was not related to alcohol use (OR=0.72, 95% CI 0.12–4.21). Having HIV-related policies and services at the sex work venue was found to be marginally related to alcohol use (p=0.06).

At the personal level, educational achievement and age of FSWs predicted the likelihood of alcohol use by the women prior to having paid sex. Those with no more than an elementary education were less likely than their better educated counterparts to report drinking alcohol with their clients prior to paid sexual intercourse (OR=0.38, 95% CI 0.18–0.80). Younger FSWs (25 years of age or less) also were less likely than their older peers to report alcohol consumption with their clients before sex (OR=0.42, 95% CI 0.22–0.80). Additionally, a marginal association was noted between marital status and alcohol use (p =0.065), a finding that suggests that married FSWs may be less likely to use alcohol (OR=0.46, 95% CI 0.20–1.05). FSWs' knowledge of HIV transmission, however, was unrelated to alcohol use (OR=1.00, 95%CI 0.90–1.12).

At the client level, results show that FSWs were less likely to have used alcohol before sex with new clients (OR=0.61, 95% CI 0.44–0.84). Additionally, a marginal association was noted between origin of client and alcohol use (p = 0.07), which suggests that FSWs may be more likely to use alcohol with domestic/local Indonesian clients than with clients from elsewhere (OR=1.32, 95% CI 0.86–2.02).

DISCUSSION

Alcohol use appears common among FSWs in Senggigi prior to sexual intercourse with their clients. Use was found to vary by sex work venue with higher rates of alcohol consumption before sex among freelancers seeking clients at discotheques and bars than among those who solicit clients at brothels or recreational enterprises such as karaoke bars and massage parlors. This finding supports the study's initial premise that the work environment in which FSWs meet their clients influences their alcohol use. It also is consistent with previous research (Chiao et al., 2006) indicating that contextual factors help to determine FSW's drinking behavior. Contrary to our initial expectations, however, supportive versus non-supportive management style did not predict alcohol use prior to paid sex. We did, however, find marginal support for the hypothesis that FSWs were less likely to drink alcohol before sex with their clients when establishments implemented HIV-related policies and services.

At the individual level, FSW educational achievement and age were related to alcohol use before paid sex. Specifically, FSWs who were age 25 or older and those with more than an elementary education were the more likely to use alcohol prior to commercial sex than their younger and less educated counterparts. This finding may reflect the fact that older and better educated FSWs also are the more likely to work at karaoke establishments or discotheques where alcohol is commonly consumed and its use is encouraged. Our data also show that irrespective of venue, the FSWs whom we sampled could only answer about half of the questions about HIV transmission that are common to AIDS knowledge scales. This finding reaffirms the need to encourage and provide more effective HIV education for these high-risk women.

Of additional interest, sexual exchanges with new as opposed to regular clients also predicted the likelihood of alcohol use, with a greater tendency for alcohol consumption before sex with regular clients. Possibly when FSWs see a client on a regular or even occasional basis, they develop a more personal relationship that includes convivial alcohol consumption. Indeed, several previous studies have noted this finding (Day, Ward, & Perrotta, 1993; Havanon, Bennett, & Knodel, 1993; Morris et al., 1995; Morris et al., 1996).

Given the key role that they potentially can play in encouraging HIV risk-reduction (Dworkin and Ehrahardt, 2007), venue owners and managers should be encouraged to implement HIV prevention for FSWs by integrating education and support for safer alcohol use into their establishment policies. Special HIV prevention efforts also must be made to target freelance workers who see clients outside of an employer relationship. Successful strategies to do so include identifying and training FSW key indigenous leaders whose beliefs, practices, and behaviors are seen and imitated by others (Wiebel, 1993). Messages aimed at targeting FSWs also should emphasize that HIV can be contracted through unprotected sex with clients of all backgrounds and types. Concepts that encourage risk reduction from the Behavior Change Communication (BCC) strategy (MAP, 2004; MAP, 2005), the Indigenous Leader Outreach Model (ILOM) (Wiebel, 1993) and alcohol and HIV risk-reduction counseling (Kalichman et al., 2007) could be adopted.

This research investigation has several limitations. First, we used an egocentric network study design (Morris, 2004) that relied on FSWs' proxy reporting of client and venue level data. This method limited our ability to collect in-depth information regarding client-level variables that the literature identifies as being associated with alcohol use including the clienteles' religion, education, and occupation. Therefore, we were unable to consider or adjust for these factors when examining study hypotheses. Additionally, the possibility also exists that two or more sex workers may have engaged in paid sex with and reported on the same client. Consequently while our data report on 326 client interactions, we have no way of knowing if this number represents 326 separate individuals. Another limitation is that more detailed assessments of alcohol consumption were not collected during the interviews. We must leave it to other research to analyze venue differences in alcohol consumption by such key factors as patterns of use, frequency, duration, and quantity of alcohol consumption. Also, the number of units nested at each level was relatively small, which may lead to less precise findings. This limitation, however, is generally not considered problematic when employing hierarchical modeling because of the robust nature of their estimation methods (Luke, 2004; Raudenbush et al., 2002). It is also noteworthy that this study was based on self-report data regarding sensitive behaviors and thus may be subject to recall and self-presentation bias (Bancroft, 1997; Harrison & Hughes, 1997). We attempted to decrease these threats to validity by building rapport with respondents and by assuring them privacy and confidentiality in answering, as well as discussing the importance of their answers to efforts to address the multiple heath problems facing FSWs.

In summary, numerous studies acknowledge the importance of investigating the influence of sex work venue in shaping FSWs' risk behavior (Nguyen et al., 2000; Schensul, Levy, & Disch, 2003; Morisky et al., 1998; Morisky et al., 2002; Morisky et al., 2005; Morisky et al., 2006; Outwater et al., 2000; Ford, Wirawan, & Fajans, 1998; Ford et al., 2000; Hugo, 2001; Joesoef et al., 1997). Few investigators, however, have examined contextual effects in a robust manner. This study extends this literature by investigating both contextual and other factors predicting alcohol use among FSWs paid to provide sex. In particular, the venue type within which FSWs solicit customers was demonstrated to predict alcohol consumption. Future research should build on these findings by exploring the frequency of alcohol intake and other substance use behaviors with this group and/or their clients, and by evaluating programs designated to reduce alcohol consumption and other HIV behaviors among these at-risk populations.

Acknowledgements

Support for this study has been provided by The Fogarty AIDS International Training and Research Program at University of Illinois at Chicago (D43 TW001419). We would also like to thank Steve Wignall MD, Chief Operations Officer of SEAICRN for his input and advice.

This study was supported by the Fogarty AIDS International Training and Research Program at University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) whom funded the first author doctoral training in public health at UIC (D43 TW001419).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

A Conflict Of Interest Statement We, hereby certify that no financial support or benefits have been received by us from the tobacco, alcohol, pharmaceutical or gaming industries, and no contractual constrains on publishing imposed by the funder.

References

- Bancroft J. Researching Sexual Behavior: Methodological Issues. University of Indiana Press; Bloomington, IN: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett LR. Working Paper No.6, Gender Relations Centre, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies. The Australian National University; Canberra: 2000. Sex, Power and Magic Constructing and Contesting Love Magic and Premarital Sex in Lombok. Retrieved August 10,2010: http://rspas.anu.edu/grc/publications/pdfs/WP_6_Bennett.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Binson D, Woods WJ. A theoretical approach to bathhouse environments. Journal of Homosexuality. 2003;44:23–31. doi: 10.1300/J082v44n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brents BG, Hausbeck K. Violence and legalized brothel prostitution in Nevada: examining safety, risk, and prostitution policy. J Interpers Violence. 2005;20:270–295. doi: 10.1177/0886260504270333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EJ, Van Hook M. Risk behavior, perceptions of HIV risk, and risk-reduction behavior among a small group of rural African American women who use drugs. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2006;17:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chersich MF, Luchters SM, Malonza IM, Mwarogo P, King'ola N, Temmerman M. Heavy episodic drinking among Kenyan female sex workers is associated with usafe sex, sexual violence and sexually transmitted infections. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18:764–9. doi: 10.1258/095646207782212342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiao C, Morisky DE, Rosenberg R, Ksobiech K, Malow R. The relationship between HIV/Sexually Transmitted Infection risk and alcohol use during commercial sex episodes: results from the study of female commercial sex workers in the Philippines. Substance Use & Misuse. 2006;41:1509–1533. doi: 10.1080/10826080600846284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day S, Ward H, Perrotta L. Prostitution and risk of HIV: male partners of female prostitutes. BMJ. 1993;307:359–61. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6900.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SL, Ehrhardt AA. Commentary: Going Beyond “ABC” to Include “GEM”: Critical Refelctions on Progress in the HIV/AIDS Epidemic. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(1):13–18. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.074591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fajans P, Ford K, Wirawan DN. AIDS knowledge and risk behaviors among domestic clients of female sex workers in Bali, Indonesia. AIDS Care. 1994;6:459–75. doi: 10.1080/09540129408258661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford K, Wirawan DN, Fajans P. AIDS knowledge, risk behaviors and condom use among four groups of female sex workers in Bali, Indonesia. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes and Human Retro Virology. 1995;10:569–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford K, Wirawan DN, Fajans P. Factors related to condom use among four groups of female sex workers in Bali, Indonesia. AIDS Educ Prev. 1998;10:340–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford K, Wirawan DN, Reed BD, Muliawan P, Sutarga M. AIDS and STD knowledge, condom use and HIV/STD infection among female sex workers in Bali, Indonesia. AIDS Care. 2000;12:523–534. doi: 10.1080/095401200750003716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford K, Wirawan DN, Muliawan P, Wolfe R. The Bali STD/AIDS study: evaluation of an intervention for sex workers. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:50–8. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200201000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford K, Wirawan DN. Condom use among brothel-based sex workers and clients in Bali, Indonesia. Sex Health. 2005;2:89–96. doi: 10.1071/sh04051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison L, Hughes A. The Validity of Self-Reported Drug Use: Improving the Accuracy of Survey Estimates. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Rockville, MD: 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havanon N, Bennett A, Knodel J. Sexual networking in provincial Thailand. Stud Fam Plann. 1993;24:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugo GJ. Report of Population Mobility and HIV/AIDS in Indonesia. The United Nations of Development Program. South East Asia HIV and Development Programme, UNAIDS and International Labour Organization (ILO); Indonesia: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Joesoef MR, Linnan M, Barakbah Y, Idajadi A, Kambodji A, Schulz K. Patterns of Sexually Transmitted Diseases in Female Sex Workers in Surabaya, Indonesia. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 1997;8:576–580. doi: 10.1258/0956462971920811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joesoef MR, Kio D, Linnan M, Kambodji A, Barakbah Y, Idajadi A. Determinants of condom use in female sex workers in Surabaya, Indonesia. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2000;11:262–265. doi: 10.1258/0956462001915679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Jooste S. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review of empirical findings. Prev Sci. 2007;8:141–51. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan D, Ellen JM, Moreno L, Rosario S, Katz J, Celentano DD, Sweat M. Environmental-structural factors significantly associated with consistent condom use among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. AIDS. 2003;17:415–423. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200302140-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein H, Levy JA. Shooting Gallery Users & HIV Risk. Journal of Drug Issues. 2003;33:751–768. [Google Scholar]

- Lim LL. The Sex Sector: The economic and social bases of prostitution in Southeast Asia. International Labour Office; Geneva: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Luke DA. Multilevel Modeling. Sage Publication Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Madhivanan P, Hernandez A, Gogate A, Stein E, Gregorich S, Setia M, et al. Alcohol use by men is a risk factor for the acquisition of sexually transmitted infections and human immunodeficiency virus from female sex workers in Mumbai, India. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:685–90. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000175405.36124.3b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of the Republic Indonesia (MOH) Central Bureau of Statistics (BPS) US Agency for International Development (USAID) National AIDS Commission (KPAN) Family Health International-Aksi Stop AIDS (ASA) Program . Integrated Biological-Behavioral Surveillance of Most-at-Risk Groups (MARG) Jakarta: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Monitoring the AIDS Pandemic (MAP) Face the Facts. International Programs Center, U.S. Bureau of the Census and Family Health International; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Monitoring the AIDS Pandemic (MAP) Report on Sex work and HIV/AIDS in Asia. International Programs Center, U.S. Bureau of the Census; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Morisky DE, Tiglao TV, Sneed CD, Tempongko SB, Baltazar JC, Detels R, et al. The effects of establishment practices, knowledge and attitudes on condom use among Filipina sex workers. AIDS Care. 1998;10:213–220. doi: 10.1080/09540129850124460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky DE, Pena M, Tiglao TV, Liu KY. The impact of the work environment on condom use among female bar workers in the Philippines. Health Education and Behavior. 2002;29:461–472. doi: 10.1177/109019810202900406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky DE, Chiao C, Stein JA, Malow R. Impact of social and structural influence interventions on condom use and sexually transmitted infections among establishment-based female bar workers in the Philippines. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality. 2005;17:45–63. doi: 10.1300/J056v17n01_04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky DE, Stein JA, Chiao C, Ksobiech K, Malow R. Impact of a social influence intervention on condom use and sexually transmitted infections among establishment-based female sex workers in the Philippines: A Multilevel Analysis. Health Psychology. 2006;25:595–603. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.5.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris M, Pramualratana A, Podhisita C, Wawer MJ. The relational determinants of condom use with commercial sex partners in Thailand. AIDS. 1995;9:507–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris M, Podhisita C, Wawer MJ, Handcock MS. Bridge populations in the spread of HIV/AIDS in Thailand. AIDS. 1996;10:1265–1271. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199609000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris M. Sexual networks and HIV. AIDS. 1997;11:209–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris M. Network Epidemiology: A Handbook for Survey Design and Data Collection. Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TTT, Linden CP, Nguyen XH, John B, Ha BK. Sexual risk behavior of women in entertainment services in Vietnam. AIDS and Behavior. 2000;4:S93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ouellet L, Jimenez AD, Johnson WA, Wiebel WW. Shooting galleries and HIV disease: variations in places for injecting illicit drugs. Crime & Delinquency. 1991;37:64–85. [Google Scholar]

- Outwater A, Nkya L, Lwihula G, O'Connor P, Leshabari M, Nguma J. Patterns of partnership and condom use in two communities of female sex workers in Tanzania. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2000;11:46–54. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60395-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant MA. Alcohol, Sex and AIDS. Alcohol & Alcoholism. 1990;25:293–301. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a045003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant ML, Plant MA, Thomas RM. Alcohol, AIDS risks and commercial sex: some preliminary results from a Scottish study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1990;25:51–5. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(90)90141-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podhisita C, Wawer MJ, Pramualratana A, Kanungsukkasem U, McNamara R. Multiple sexual partners and condom use among long-distance truck drivers in Thailand. AIDS Educ Prev. 1996;8:490–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Cheng DM, Levison R, Meli S, Samet JH. Sex trade, sexual risk, and nondisclosure of HIV serostatus: findings from HIV-infected persons with a history of alcohol problems. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:149–57. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Cheong YF, Congdon R, Du Toit M. Linear and NonLinear Modeling. Scientific Software International; Lincolnwood, IL: 2002. HLM 6: Hierarchical. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T. The “risk environment': a framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2002;13:85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Riono P, Jazant S. The current situation of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Indonesia. AIDS Educ Prev. 2004;16:S78–90. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.3.5.78.35531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safika I. PhD [dissertation] University of Illinois at Chicago; Chicago: 2009. The Influence of Sex Work Venues on Condom Uses Among Female Sex Workers in Senggigi, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Sedyaningsih-Mamahit ER. Female sex workers in Kramat Tunggak, Jakarta, Indonesia. Social Science & Medicine. 1999;49:1101–1114. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schensul JJ, Levy JA, Disch WB. Individual, contextual, and social network Factors affecting exposure to HIV/AIDS risk among older residents living in low-income senior housing complexes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33:S138–52. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200306012-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surtees R. Traditional and Emergent Sex Work in Urban Indonesia. Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context. 2004;(10) Retrieved August 10, 2010: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue10/surtees.html.

- Thorpe L, Ford K, Fajans P, Wirawan DN. Correlates of condom use among female prostitutes and tourist clients in Bali, Indonesia. AIDS Care. 1997;9:181–197. doi: 10.1080/09540129750125208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tempalski B, McQuie H. Drugscapes and the role of place and space in injection drug use-related HIV risk environments. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2009;20:4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran TN, Detels R, Long HT, Van Phung L, Lan HP. HIV infection and risk characteristics among female sex workers in Hanoi, Vietnam. Journal of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2005;39:581–586. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran TN, Detels R, Lan HP. Condom use and its correlates among female sex workers in Hanoi, Vietnam. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:59–167. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Li X, Stanton B, Chen X, Liu H, Fang X, et al. HIV-related risk factors associated with commercial sex among female migrants in China. Health Care Women Int. 2005;26:134–48. doi: 10.1080/07399330590905585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebel W. The Indigenous Leader Outreach Model: Intervention Manual. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Rockville, MD: 1993. [Google Scholar]